The Definitives

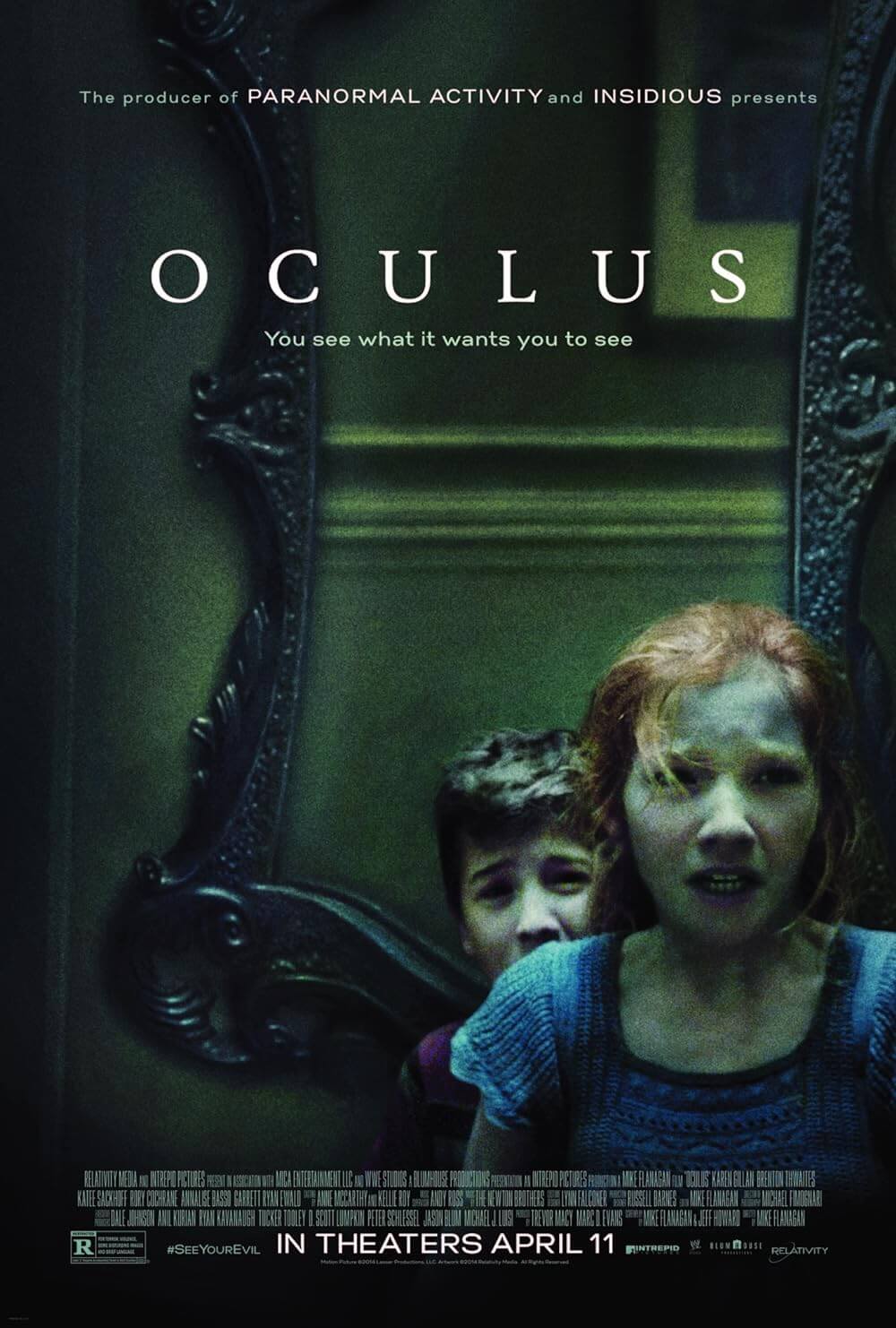

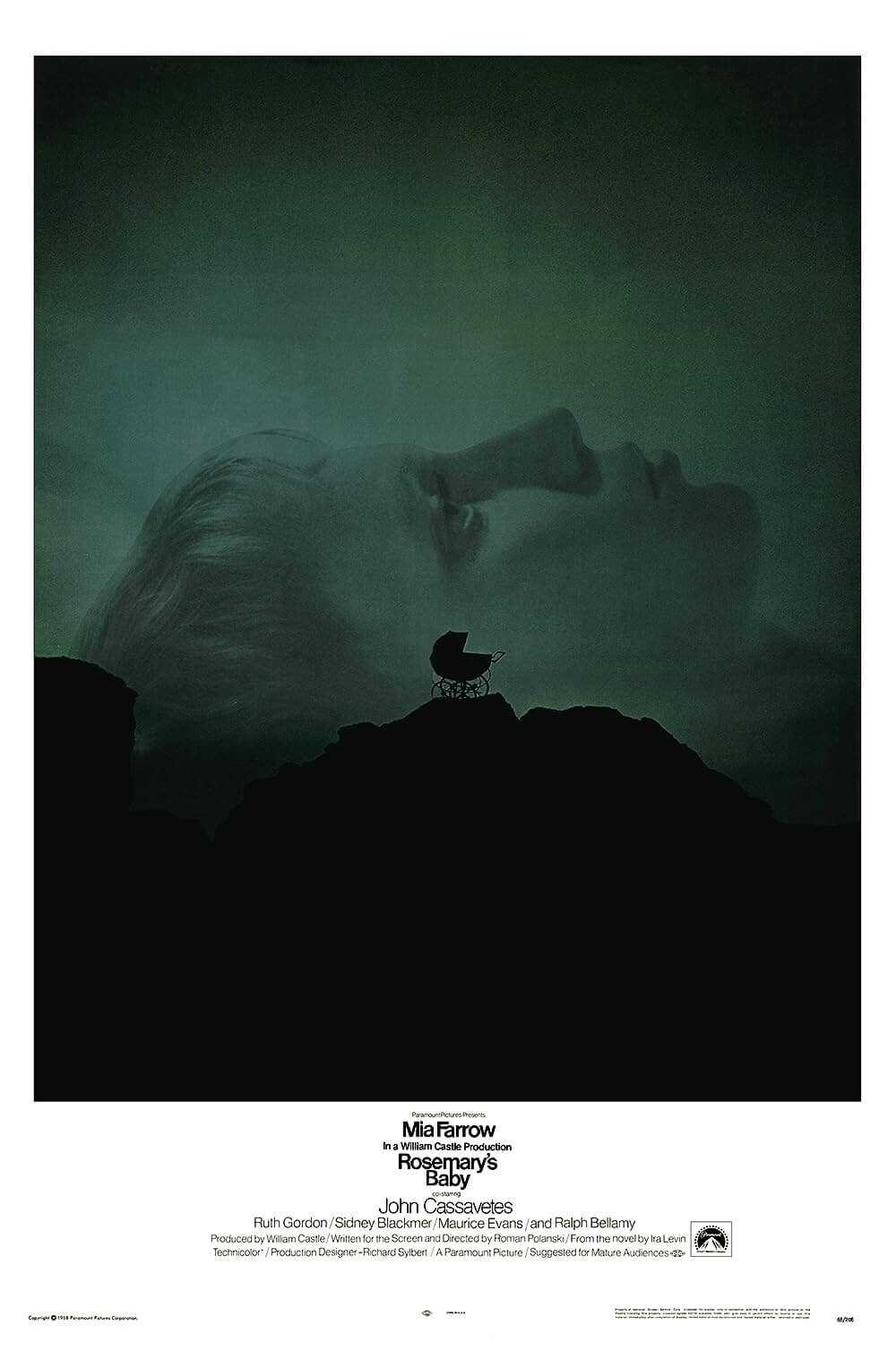

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Rosemary’s Baby builds tension with masterful patience and detail, not because it relies entirely on the payoff of its devilish finale, but because Roman Polanski wants to submerge the viewer in paranoia. Through his meticulous study of characters, their naturalistic mannerisms and peculiarities, and the weight he applies to even immaterial trivialities, Polanski constructs a very real sense of horror. Through it, he raises an atmosphere of instability that counteracts his picture’s supernatural menace with a practical skepticism, almost in the same moment that he confirms our worst, most unimaginable fears. Not until the final act does the film reveal itself as a tale of supernatural terror. Though perhaps Rosemary’s Baby remains more alarming for its depiction of a powerless housewife trying to regain agency over her pregnancy and herself. Polanski’s ability to evoke such a particular, seemingly realistic dread of cultism in 1968 resulted in potent reactions, including protests from the Christian right and accusations that the film portrayed actual Satanic rituals. The response foreshadowed the cultural paranoia that later saturated protests and commentary in the media over the following decades, anticipating the so-called Satanic Panic and its attempts to censor films and television that were believed to contain base morals and actual Satanic practices. Such is the power of Rosemary’s Baby over its audience—a thriller so intricate and haunting that it laid the foundation of a subsequent cultural mania, and in that established its unshakable place in cinematic history.

To understand the potent reactions to this film, it’s important to consider the historical moment at which it arrived and remarked upon. In the 1960s, the authority of the Catholic church waned under the rise of alternative belief systems, including atheism and a renewed fascination with the occult and black magic. Rampant disenchantment with and questioning of Christian ideals brought about a cultural suspicion toward long-established religious ideologies. This trend was never better encapsulated than the cover of Time magazine on their April 1966 issue, which asked “Is God Dead?” in bold red letters on a black background. That Time could feature such a cover signaled the pervasive anxieties of the era, mindful of the full extent of World War II’s atrocities, the prevailing Vietnam War, the Nixon presidency, godless Communists engaging in the Cold War, and the views of several death-of-God theologians gaining popularity in the cultural sphere. Although the cover story, championed by Time editor Otto Fuerbringer, questioned the relevance of God in a seemingly godless time, many took the story literally, believing that evil had replaced the now-dead God. This emergent ideological viewpoint signaled a major change in the culture war—it was a threat to those who firmly followed Christianity, but also those who believed the associations gave way to Satanism and certain criminal activities. The emergence and awareness of actual Satanic cults in the U.S., with early markers such as Rosemary’s Baby, fueled the fervor and hardened the position of religious groups.

A Jewish-born atheist, author Ira Levin explored the culture’s feelings of religious disenchantment with his best-selling novel, Rosemary’s Baby, published in 1967. Author of The Boys from Brazil and the pseudo-feminist tale The Stepford Wives, Levin upheld potboiler pacing in his book, even while maintaining a naturalistic approach to his horror intent. But never does Levin’s reader hesitate or doubt the titular protagonist as much as the viewer of the film, which functions as a macabre comedy for much of its runtime. The book was adapted into a motion picture the following year by Polanski and producer Robert Evans at Paramount Pictures, not long after the Time magazine story and, in fact, the issue appears in one scene in a doctor’s waiting room. To be sure, the film exploits the fears of its audience, fueling tensions with a paranoid plot about a cultish underworld. Polanski preserves simultaneous belief and distrust toward of the situation; he whirls about confirmations and denials for every horrid possibility. From muffled sounds heard through the walls to the genial dispositions of his characters, even the evil ones, the viewer second-guesses themselves and the protagonist throughout, until, of course, Polanski confirms our misgivings. And like Levin’s book, Polanski observed how moral polarities of good and evil are transcended by human desires, a tenet of Satanism.

Mia Farrow stars as Rosemary Woodhouse, a soon-to-be-expectant mother who comes to believe a coven of witches scheme to steal her unborn baby for a human sacrifice. But before any talk of witches or occult conspiracies, Polanski spends about an hour outlining his characters, their relationships, eccentricities, insecurities, and desires. Rosemary and her husband, Guy (John Cassavetes), move into the Bramford, a Gothic apartment complex in New York City. Polanski shot on location at The Dakota, the Central Park West building outside of which John Lennon was killed in 1980. Rosemary is naïve, delicate and childlike. She spends her days decorating their new home, busying herself any way she can, tiptoeing around her irritable husband. In a crucial characteristic, she’s been taught to accommodate and obey, to not make a fuss and serve her husband like many unfortunate housewives—a detail that become important later on when she refuses to stand up for herself, despite obvious misgivings about the people who continue to make decisions about her life and eventual pregnancy. Meanwhile, Guy struggles to become a big-time actor, finding only roles on television commercials and bit theater productions. He talks fast, finds a joke anywhere, and frequently does voices that make Rosemary giggle. She wants a baby, but he wants to wait to have a child until his acting becomes more stable. Everything is in front of them.

Another occupant, Terry (credited as Angela Dorian, but yes, indeed, she is model Victoria Vetri), a laundry room acquaintance of Rosemary, lives with their elderly neighbors, the Castevets. Later, Terri commits suicide for what seems no reason at all. These aging, cheerfully eccentric neighbors, Minnie (Ruth Gordon) and Roman Castevet (Sidney Blackmer), introduce themselves immediately after Terry’s death. Minnie peeks in Rosemary’s apartment door to get a look at their renovations and invites the Woodhouses over for dinner. Obligated to a friendly meal out of sympathy, Rosemary and Guy visit the stuffy apartment next door for some of Minnie’s bad cooking and Roman’s stories about world travel. A discussion ensues about religion and the Pope, and Roman remarks, “You don’t need to have respect for him because he pretends that he’s holy.” Guy agrees. Rosemary, who was raised Catholic, feels uncomfortable talking about it. After the dinner, Minnie becomes meddlesome, poking her nose in their affairs. And though Rosemary wants nothing more to do with them, Guy keeps visiting for more of Roman’s stories, whispered in the next room over a drink and a smoke.

The film’s details consume us, such as how three-dimensional these characters feel. However cute and flirty Guy and Rosemary appear, she’s a product of a male-dominated culture and thus behaves like a garnish to her husband. Being a lonely housewife, she talks to herself and has an active headspace. She remains meek when voicing her opinion. Guy tries to behave like an understanding husband sensitive to his wife’s needs, but his apologetic control of Rosemary is apparent, no matter how much he seems to be grappling with some inner guilt about his impulses. Elsewhere, Minnie fusses over messes and asks about the cost of Rosemary’s new furniture, like a grandmother, and Roman has been everywhere. “You name a place, I’ve been there.” They’re an exceedingly banal couple, fascinatingly so. The credit for some of these details belongs to the actors who bring their characters to life. Watch Gordon’s Minnie in her keen surveillance of Guy’s enjoyment of her cake, or the way Farrow’s Rosemary bounces with excitement. But Polanski also layers seemingly inconsequential conversations with curious facets that prove significant later. Embedded into talk about washing dishes or plans for the future, Minnie probes Rosemary about her good health, her intent to have children, her fertile family history. Is this idle conversation, or is there something more to it? Polanski keeps us guessing.

The film’s details consume us, such as how three-dimensional these characters feel. However cute and flirty Guy and Rosemary appear, she’s a product of a male-dominated culture and thus behaves like a garnish to her husband. Being a lonely housewife, she talks to herself and has an active headspace. She remains meek when voicing her opinion. Guy tries to behave like an understanding husband sensitive to his wife’s needs, but his apologetic control of Rosemary is apparent, no matter how much he seems to be grappling with some inner guilt about his impulses. Elsewhere, Minnie fusses over messes and asks about the cost of Rosemary’s new furniture, like a grandmother, and Roman has been everywhere. “You name a place, I’ve been there.” They’re an exceedingly banal couple, fascinatingly so. The credit for some of these details belongs to the actors who bring their characters to life. Watch Gordon’s Minnie in her keen surveillance of Guy’s enjoyment of her cake, or the way Farrow’s Rosemary bounces with excitement. But Polanski also layers seemingly inconsequential conversations with curious facets that prove significant later. Embedded into talk about washing dishes or plans for the future, Minnie probes Rosemary about her good health, her intent to have children, her fertile family history. Is this idle conversation, or is there something more to it? Polanski keeps us guessing.

In the initial scenes, the audience is overwhelmed by mounting suspicions, which then go overlooked. The Castevets seem nice enough, but little irregularities about the building and their new neighbors emerge everywhere, arousing our dread. The previous tenant, an elderly woman who died in a coma, left unfinished scribblings declaring, “I can no longer associate myself with…” She also pulled a heavy wooden secretary in front of her hallway closet. One night, as Rosemary is half-sleeping, strange chanting can be heard through the walls, coming from the Castevet’s apartment. Minnie gives Rosemary a charm, the same one that was around Terry’s neck when she committed suicide. Rosemary’s friend Hutch (Maurice Evans) mentions that the Bramford used to house a coven of infamous cannibal witches, among other notorious occultist figures. Guy, who used to complain about the annoying neighbors, continues to spend his evenings with them. Suddenly, he starts saying “They’re not so bad.” Then Guy wants to have a baby; he even “figured out” Rosemary’s ovulation cycle. Tonight’s the night. Not to intrude, Minnie sends over some chocolate “mouse” desert. Guy loves it, but Rosemary takes only a few bites and pours the rest out. It tastes funny.

Realistic mise-en-scène shrouds the elements of horror in a Roman Polanski film, so that which remains suspect also feels too real and inconsequential to possibly delve into horror territory. His scares arise not from supernatural origins, but from psychological possibility—the horrible things people will do if so compelled. Polanski specializes in obsessions and madness, particularly those supplied within a limited space. Prior to this film, he made Repulsion in 1965, and then after it The Tenant in 1976. Consider these a thematic trilogy. Each takes place in an increasingly confining apartment, the respective protagonists wary of neighbors, sounds, and the history of the building itself. The walls seem to gradually close in and suffocate the interior, whereas the world inside their heads has long since gone mad. These films each force the audience to question the reliability of the central character. Is the world really out to get them, or are their fears a symptom of some mental malady? Perhaps in the other two films, the viewer could see the conflict as one perpetuated by the internal anxieties and mental instabilities of their protagonists, but not in Rosemary’s Baby.

Dizzying, hallucinatory dreams ensue after Rosemary eats the mousse desert. The film’s dream sequences continue to puzzle today, as Polanski constructed them so much like actual dreams—not typical soft-filtered movie dreams, but an overexposed nightmare of mish-mashed imagery. Voices around the apartment seem to penetrate Rosemary’s unconscious, as if Polanski were showing us two truths at once. Images flow in and out of frame. Nothing makes logical sense, and yet it all congeals in an effortless sort of way. Guy begins to undress her. Rosemary appears on a boat captained by JFK. Hutch cannot join her; the boat is for Catholics only. She floats on scaffolding underneath Michelangelo’s ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Naked figures emerge all around her. A feathered creature of some kind scrapes its claws on her flesh and begins to rape her. The Pope appears during the act, so that Rosemary might kiss his ring: the charm Minnie gave her. Rosemary announces, “This is no dream, this is really happening!” How can anyone be certain?

Guy seems distant the morning after Rosemary’s dream. She questions the Scratch-marks on her body. He promises that he already filed down his nails, and that he made love to her as she slept, not wanting to miss making a baby. “It was kind of fun in a necrophile sort of way,” he says. “I didn’t want to miss baby night” becomes a strange and unsettling apology for raping his unconscious wife. Sometime later, Rosemary is pregnant. She forgoes seeing her initial obstetrician again when the Castevets insist on their high society doctor friend—the best in the city, Dr. Abe Sapirstein (Ralph Bellamy), who warns, “Please don’t read books… And don’t listen to your friends, either.” Sapirstein also insists that Rosemary’s weight loss and constant pain are normal. Hutch thinks otherwise, and in a chance meeting with Roman, voices as much. When Hutch ends up in a sudden coma, Rosemary is all alone. Her friends help, telling her that months of pain aren’t normal. And just when her pain brings her to the brink of cracking and seeing someone other than Sapirstein, her pain goes away.

Despite her obvious manipulation by those around her, we doubt Rosemary at first—a reaction Polanski expects and uses to his advantage. She comes off childish and innocent, therefore her actions and behaviors are uncertain. When her first obstetrician, Dr. Hill (Charles Grodin), asks for another sample of blood to test her blood sugar, she questions it, whispering “blood sugar” to herself in undue suspicion. Perhaps she welcomed Dr. Sapirstein for that reason. Rosemary becomes hyper-sensitive to many small details during her pregnancy out of justified mistrust, and some out of, as Polanski suggests, natural hormonal anxieties, later explained away as pre-partum depression. When she complains, Guy responds, “There’s always something wrong.” She seems so unsure of what to do, and the characters around her, Guy and the Castevets, respond by claiming to know better or even making choices about her body. They order her around, such as Minnie insisting that Rosemary wear the tannis root charm necklace, regardless of its stink. “You’ll get used to the smell before you know it.” Or when Rosemary refuses to eat Minnie’s chalky-tasting dessert, Guy turns the moment into a familiar dinner table scene, as though his wife were a child refusing to eat her lima beans. “Come on. The old bat slaved all day. Now eat it.” Rosemary’s own submissiveness and lack of agency seal her child’s fate.

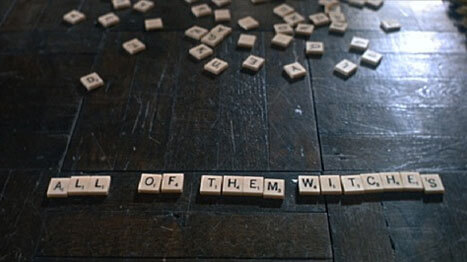

Hints to her Catholic upbringing and religious images in her many dreams warn of ingrained religious-based fears, countered by the delusional thought that something sinister plots against her. Polanski implants the notion that Rosemary has fallen prey to hysterics, so the audience begins to doubt its misgivings about the suspicious behavior of those around her. Couldn’t it all just be a terrible case of coincidence and paranoia? When Hutch, who encouraged Rosemary’s worst fears, ends up dead, he leaves her a witchcraft book, entitled All of Them Witches, which seems to confirm that Roman was the ancestor of a notorious Bramford witch. Guy adamantly defends his neighbor friend, believing her anxiety stems from Hutch putting ideas in her head. But then, Guy is too busy worrying about his sudden success, his starring role in a new choice play, won when the previous actor went inexplicably blind. Rosemary runs, believing Guy, the Castevets, Minnie’s sewing circle of friends, all of them—witches. She seeks help from Dr. Hill, who calls her husband and Sapirstein to retrieve her. She attempts to escape, but they catch her, and then she goes into labor.

Hints to her Catholic upbringing and religious images in her many dreams warn of ingrained religious-based fears, countered by the delusional thought that something sinister plots against her. Polanski implants the notion that Rosemary has fallen prey to hysterics, so the audience begins to doubt its misgivings about the suspicious behavior of those around her. Couldn’t it all just be a terrible case of coincidence and paranoia? When Hutch, who encouraged Rosemary’s worst fears, ends up dead, he leaves her a witchcraft book, entitled All of Them Witches, which seems to confirm that Roman was the ancestor of a notorious Bramford witch. Guy adamantly defends his neighbor friend, believing her anxiety stems from Hutch putting ideas in her head. But then, Guy is too busy worrying about his sudden success, his starring role in a new choice play, won when the previous actor went inexplicably blind. Rosemary runs, believing Guy, the Castevets, Minnie’s sewing circle of friends, all of them—witches. She seeks help from Dr. Hill, who calls her husband and Sapirstein to retrieve her. She attempts to escape, but they catch her, and then she goes into labor.

The very real threat that exists within this film is not confirmed until the final scene. Until that point, Polanski forces us to question, Is she mad? After waking from her labor, Rosemary listens to Guy apologize about the baby dying due to “complications,” enduring his guilty smiles and transparent lies. Yet she spends days using a breast pump, and kindly neighbor Laura-Louise (Patsy Kelly) tells her the milk is just thrown away. Have witches taken her baby and used its blood in their rituals, as Hutch’s book suggested? When strong enough, with kitchen knife in-hand, Rosemary enters the Castevets’ apartment through a false wall in the hallway closet. She comes upon a gathering of well-to-dos and familiar faces, including her husband and neighbors, standing around a black crib. Everyone watches with eerie calm as she approaches it and sees her child for the first time, not butchered for witch food, but worse. Farrow’s face electrifies with terror, “Its eyes! What have you done to its eyes!” Roman announces her child’s eyes are that of his father, Satan. Jarring declarations from around the room rupture the tense silence: “Hail Satan!” “God is Dead!” “The year is One!” How impossible to convey the horror of this moment, as breathless Rosemary screams in revulsion while the fervent expressions of Satanic victory proceed around her. This moment was so real that 1960s audiences believed Polanski had actually conjured the Devil’s child.

This is where Rosemary’s Baby takes an even more disturbing turn off-screen. The film opened in 1968 to a wealth of enthusiastic reviews and incredible box-office performance, almost single-handedly saving the struggling Paramount from financial ruin; at the same time, many believed the film to be the cinematic realization of what scholar David Frankfurter called the “predatory conspiracy of Satanists.” It didn’t help that Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey served as a consultant on the film. LaVey founded the Church of Satan in 1966 and, after steadily growing for more than a decade, had gained around 5,000 members by the mid-1980s. Although the church concerned itself less with the actual worship of Satan and more with a rejection of mysticism and spirituality, the rhetoric of “church” and “Satan” poorly communicated its roots in cynical esotericism and extreme pragmatism. Such associations made Rosemary’s Baby an easy target for both the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures and the League of Decency, which labeled the film with a “C” or “condemned” rating. The root of the protests involved a fear that the film shows what’s really going on in a conspicuously detailed way. Questions about LaVey’s involvement revealed that he played the role of Satan in the scene depicting Rosemary’s rape by the devil. Elsewhere, it was customary for any film with heavily religious themes to acquire approval and endorsement from the church as a courtesy, but Polanski’s production attained no such authorizations.

Many of the protests around Rosemary’s Baby centered on Rosemary’s sexuality and almost adolescent vulnerability at times. Early in the film, her mousy behavior is given a toddlerish appearance when she cuts her hair short, making her look drastically young compared to her husband. Rosemary’s behavior, too, can sometimes be interpreted as dainty, naïve, or even pliable. Her appearance and behavior create an impression of child molestation and child sacrifice later in the film, when Rosemary has been drugged and offered as Satan’s bride. Levin and Polanski intended these associations, preying on the audience’s fears that the devil’s targets are what Christian rhetoric deem to be innocents: children and women. Their association worked perhaps too well, as the British Board of Film Censors seemed unconcerned by the depiction of Satanists; rather, they denounced the film’s “elements of kinky sex” for this reason. Later, Rosemary’s Baby would be accused of eroticizing Satanic ritual abuse on children by placing a nude adult female in the role that a child would normally play in such rituals.

The most zealous reactions against Rosemary’s Baby came more than a year after its release, when the film still lingered in a few theaters. In August of 1969, Charles Manson’s cult murdered Polanski’s then-eight-months-pregnant wife, Sharon Tate (along with five other victims, including Tate’s unborn child), and at least one of the killers had direct ties to LaVey—Susan Atkins, once a topless vampire dancer in LaVey’s “Witches’ Sabbath” show. The murders themselves were not directly tied to Satanism; their ritualistic methods were imposed to bring about “Helter Skelter,” Manson’s apocalyptic race war. Nevertheless, members of the media and right-wing Christian groups tied Tate’s murder to Rosemary’s Baby, many of them citing a hearsay remark supposedly made by Tate at a party after the film’s release: “The Devil is beautiful. Most people think he’s ugly, but he’s not.” Elsewhere, commentators blamed Polanski and Tate for bringing about their own bad luck by putting such an accurate representation of Satanism onscreen; some even accused Polanski of being a Satanist, suggesting that Tate’s murder was God’s punishment for Polanski’s associations with the devil.

The source of the reactions came from a specific ideological viewpoint held by those of Christian groups who genuinely believed that a Satanic conspiracy threatened the lives of Christians. Rosemary’s Baby was perceived to be the point of cultural normalization of Satanist concepts—a Hollywood film in which people were given a guideline for how to practice Satanic rituals. Many also believed that material such as Rosemary’s Baby contained an entrenched evil, that its filmmakers were undoubtedly compelled to produce the material by Satan himself. Although the calls for Rosemary’s Baby to be banned or censored were minimal, the film was blamed for the resulting cultural obsession with Satanism in an insurgence of popular movies involving Satanism or anti-religious themes in the 1970s. Subsequent films like Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976) created a cultural awareness and exaggeration of these phenomena. Rather than a call for direct censorship or protest, the critics that fueled the ensuing mania saturated media culture with talk of Satanist influence lurking behind certain films, television, games, and toys.

Fundamentalist Christians—who, in the decades after Rosemary’s Baby, had become a powerful political and economic fixture in American culture with a newfound strength of support in the Reagan presidency and the religious right—quickly began to organize and form an unofficial campaign against Satanic material in the media. The religious right’s ideological view deemed anything with even perceived Satanist ties as potentially dangerous and part of a larger Satanist conspiracy, and this viewpoint spread throughout the media. The movement was supported by an outpouring of films, television shows, and books that warned against Satan’s influence. Among the earliest and most formative inclusions to the movement was the 1980 publication of Michelle Remembers. The autobiographical account of a young woman who recalls repressed memories from her childhood when she was victimized in Satanic ritual abuse chilled readers, though it was later debunked. Similar survivors were given a showcase on talk shows like The Phil Donahue Show or Geraldo Rivera’s 1988 prime-time showcase “Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground” on NBC. Satanism became an entrenched cultural topic, and any alleged evidence of its presence in entertainment was targeted in an ideological witch hunt known as the Satanic Panic.

Fundamentalist Christians—who, in the decades after Rosemary’s Baby, had become a powerful political and economic fixture in American culture with a newfound strength of support in the Reagan presidency and the religious right—quickly began to organize and form an unofficial campaign against Satanic material in the media. The religious right’s ideological view deemed anything with even perceived Satanist ties as potentially dangerous and part of a larger Satanist conspiracy, and this viewpoint spread throughout the media. The movement was supported by an outpouring of films, television shows, and books that warned against Satan’s influence. Among the earliest and most formative inclusions to the movement was the 1980 publication of Michelle Remembers. The autobiographical account of a young woman who recalls repressed memories from her childhood when she was victimized in Satanic ritual abuse chilled readers, though it was later debunked. Similar survivors were given a showcase on talk shows like The Phil Donahue Show or Geraldo Rivera’s 1988 prime-time showcase “Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground” on NBC. Satanism became an entrenched cultural topic, and any alleged evidence of its presence in entertainment was targeted in an ideological witch hunt known as the Satanic Panic.

Reactions to and beliefs in Satanic conspiracy led to an increasing cultural paranoia, which reached its zenith in the 1980s and 1990s, with films and television often cited as a source of conspiratorial brainwashing, and therein the subject of warnings to parents. A belief in conspiracy is part of American culture more than most others—be it notions of an alien landing in Roswell, the Illuminati, the assassination of JFK, or the formative influence of Freemasons throughout history. Satanism was the latest conspiracy fad. Fundamentalist Christians suddenly saw Satanic influence everywhere on the media landscape, accusing games like Dungeons and Dragons and cartoons like Care Bears, The Smurfs, and He-Man and the Masters of the Universe of containing “occult imagery” that sought to corrupt children by introducing unholy images into homes through a half-hour animated show, and the slew of associated toys and action figures. Philosopher and theologian Carl Raschke, whose writings in the 1980s helped fuel Satanic hysteria of the period, suggested that the people had become so nihilistic that the only explanation could be that Satan was motivating their behavior through the Satanist themes in contemporary media.

And while actual Satanists remained under ten thousand in the U.S., the reactions to the presence of Satanists became a widespread movement and social phenomenon predicated on the religious right’s ideological stance. A multi-tiered organization of anticult publications, talk shows, radio broadcasts, and televangelist commentary treated the growth of Satanism matter of factly, citing holy scripture for having predicted the rise of Satan, and thus issuing a decree that it was the duty of all real Christians to warn others about the threat of Satanism. Moreover, those who were not god-fearing Christians, or inhabiting said values, were undoubtedly devil-worshippers worthy of condemnation in the eyes of these anti-Satanist groups. Therefore, many of the new religious groups that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, which provided an alternative lifestyle to youths looking to counter their parents and society, were deemed cults—a word that itself was a social weapon meant to evoke thoughts of brainwashing, amorality, and Satanic motivations among alternative group. The emergence of Charles Manson and Jim Jones only fueled the fear of cultism, counter-cultural groups, atheistic ideas, and the questioning of authority.

By the mid-1980s, the Satanic Panic movement proved so successful because those using the rhetoric could connect their concerns to nonreligious people by associating Satanists with criminals, as opposed to just spiritual beliefs, thus expanding their ideological stance. But those who believed that Satan was making his way into the minds of the innocent blamed the lack of cultural homogeneity that began just before the release of Rosemary’s Baby—a film that suggests the people next door could be Satanists, therefore everyone should be eyed with suspicion. The emergence of Satanism in the cultural landscape represented a decline in moral standards according to conservative Christians, and the era’s perceived increase of deviant behavior, the decline of family unity, and ignorance to child safety were symptoms of this decline. Antisatanists called attention to matters of “child abuse, missing children, child molestation, incest, child pornography, and Halloween sadism,” observed scholar Joe Best, and then associated those trends of endangered children with Satanism. To combat the criminality of Satanism, then, meant to adopt or embolden Christian values and beliefs supported by the political might of the Republican-controlled White House and its Christian fundamentalism. The alternative meant an association with the criminalized values of Satanist behavior.

The entire sordid case of Rosemary’s Baby and the resultant cultural awareness of Satansim, followed by the increase in Satanist-related films and television, and the reactions of the religious right that fueled the Satanic Panic, serve as a small case study for how film protests and censorship operate. By declaring sources such as Polanski’s film and other targets during this era not as artistic representations of Satanism but as actual Satanist practice, the religious right took an ideological stance. They presumed many things in their arguments: they presumed the existence of Satan; that the audience would be influenced by a film depicting Satan or Satanic acts; that a real threat existed in entertainment media; and that certain films and television shows, either directly or indirectly (through imagery deemed cultish, Satanist, or pagan according to commentators), supported Satan. Their message, founded or not, attempting direct censorship or not, spread views that sought to convince people of a certain ideological view that would, in turn, draw viewers away from the accused films.

As for the film itself, Polanski’s use of authentic details in the film, compounded by his personal life away from the screen, perpetuated the belief that Rosemary’s Baby was a Satanist film. Part of this is because the terror we experience from watching the film derives from what we do not see, allowing the worst fears in our imagination to take hold. Sustaining our belief, Polanski does not show the baby, but the involved viewer might see it for themselves through their gripped participation—we think we see the baby, but in actuality, the child never appears onscreen. Avoiding supernatural or doubt-worthy effects, the director leaves his finale rooted in the veracity of Rosemary’s reaction. The horror remains an idea. When Rosemary accepts that she is her child’s mother no matter its form, she rocks the carriage with a distant calm. She has finally succumbed. Some affected audiences prayed for the director who brought evil so realistically to the screen, and others feel that he got what was coming to him when his eight-months pregnant wife was killed by the Manson clan—a belief further fueled by Hollywood rumors suggesting the production was cursed. Pregnant women refused to see the film out of some arcane fear that a form of cinematic transference might take place, that the evil within the film might somehow infect their pregnancy. After all, evil is given uncharacteristic humanity through characters like Minnie and Laura-Louise, who seem more appropriate for a senior care center than a horror film. But their realism is what scared people and what continues to scare people.

Knowing how it ends layers every scene. Consider when Rosemary’s long-endured pain goes away, and her baby begins moving inside her. She cries out “It’s alive!” with joy. A happy moment for any mother instead recalls Colin Clive’s similar announcement in Frankenstein (1931), and brings to mind the resulting abomination. This may be the most disturbing moment in the film. Guy, meanwhile, carefully avoids touching her, knowing what grows inside her. When she brings his hand to her stomach as the child kicks, he recoils with a nervous reaction, as if he’s just felt a monster underneath his wife’s skin. Even the title sequence overlooking Central Park and rotating to eventually capture Rosemary and Guy in the camera’s downward gaze reminds us of Minnie’s comment in the end, how “He chose you out of all the world, out of all the women in the whole world he chose you. He arranged things because he wanted you to be the mother of his only living son.” Did Polanski intend us to revisit the film and imagine Satan looking about New York City, only to spot Rosemary? All of these moments are accentuated by the film’s music: Farrow’s own voice singing the Devil’s lullaby over the opening and ending credits. And composer Krzysztof Komeda, a longtime Polanski collaborator, composes violin strings that cry out as if the instrument itself, joined by a ghostly choir of haunted echoes, were emitting sounds from a long and numbing torture.

Knowing how it ends layers every scene. Consider when Rosemary’s long-endured pain goes away, and her baby begins moving inside her. She cries out “It’s alive!” with joy. A happy moment for any mother instead recalls Colin Clive’s similar announcement in Frankenstein (1931), and brings to mind the resulting abomination. This may be the most disturbing moment in the film. Guy, meanwhile, carefully avoids touching her, knowing what grows inside her. When she brings his hand to her stomach as the child kicks, he recoils with a nervous reaction, as if he’s just felt a monster underneath his wife’s skin. Even the title sequence overlooking Central Park and rotating to eventually capture Rosemary and Guy in the camera’s downward gaze reminds us of Minnie’s comment in the end, how “He chose you out of all the world, out of all the women in the whole world he chose you. He arranged things because he wanted you to be the mother of his only living son.” Did Polanski intend us to revisit the film and imagine Satan looking about New York City, only to spot Rosemary? All of these moments are accentuated by the film’s music: Farrow’s own voice singing the Devil’s lullaby over the opening and ending credits. And composer Krzysztof Komeda, a longtime Polanski collaborator, composes violin strings that cry out as if the instrument itself, joined by a ghostly choir of haunted echoes, were emitting sounds from a long and numbing torture.

Returning to Rosemary’s Baby again and again, one grows astounded by its humanity, which makes the film all the more effective than the standards for the genre. Farrow, Cassavetes, Blackmer, and Gordon give performances more suited for a dramedy about the struggles of a young married couple. Gordon even received a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her efforts, which helped raise the film’s esteem from the perceived lows of the horror genre. Polanski was also nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay. Then reserved for B-pictures, horror prior to the 1960s did not win awards. Polanski’s film changed that, paving the way for later pictures like The Exorcist (1973), The Fly (1986), The Silence of the Lambs (1991), and Get Out (2017). Since the release of Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, others have copied the basic plot structure or borrowed moments from this influential masterpiece, but their efforts prove less concerned with realistic psychological scares than the ending—the fantastical aspects of evil lurking in a mother’s womb. Polanski seems more interested in everything else.

Avoiding every formula associated with the period’s mass-market horror tropes, Rosemary’s Baby elevates the possibility of horror films with its artful execution, gut-wrenching tension, and reflection of its era’s religious anxieties and gender politics. Polanski’s commitment to realistic human behavior and authentic details, combined with Levin’s caution against subservient gender roles for women, tapped into the social and religious crises of the 1960s. The plot’s shocking twists may occur only on the initial viewing, of course, but they were enough to incite widespread cultural paranoia in the coming decades with the fatuous phenomenon of the Satanic Panic. On subsequent viewings, what was once paranoia becomes sheer terror, as audiences today watch as Rosemary gives up her agency to those who plot against her. Gradually, Polanski constructs an uncertain and paranoid atmosphere, as seemingly inconsequential surfaces compile into an extended nightmare, allowing the unmanageable to become more credible than initially believed. Rosemary’s Baby was unmistakably a film of its time, yet it continues to change and grow with an urgency and frightening relevance.

(Editor’s note: This article was originally published on October 3, 2009. It has been edited and expanded.)

Bibliography:

Best, Joel. “Endangered Children and Satanic Rhetoric.” The Satanism Scare. Edited by Richardson, James T., Joel Best, and David Bromley. New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1991.

Clasen, Mathias. Why Horror Seduces. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Frankfurter, David. “Awakening to Satanic Conspiracy: Rosemary’s Baby and the Cult Next Door.” Deliver Us from Evil. Edited by Eckel, David M. and Bradley L. Herling. New York: Continuum International, 2008.

Leaming, Barbara. Polanski, The Filmmaker as Voyeur: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Lima, Robert. “The Satanic Rape of Catholicism in Rosemary’s Baby.” Studies in American Fiction, no. 2, 1974, p. 211-222.

Lyons, Charles. “The Paradox of Protest.” Movie Censorship and American Culture, edited by Frances G. Couvares. Second Edition. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006, pp. 277-279.

O’Hara, Helen. “When the Devil was hot: how Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey seduced Hollywood.” The Telegraph. 15 March 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/film/the-witch/satanism-anton-lavey-hollywood/. Accessed 19 November 2017.

Parker, John. Polanski. London, 1994.

Polanski, Roman. Roman by Polanski. New York: Morrow, 1985.

Richardson, James T. et al. The Satanism Scare. New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1991.

Sandford, Christopher. Polanski: A Biography. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review