The Definitives

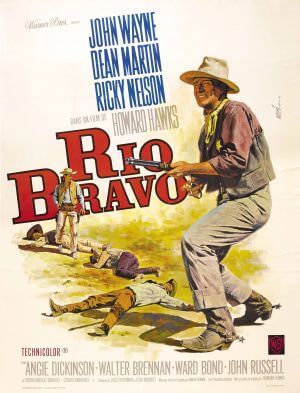

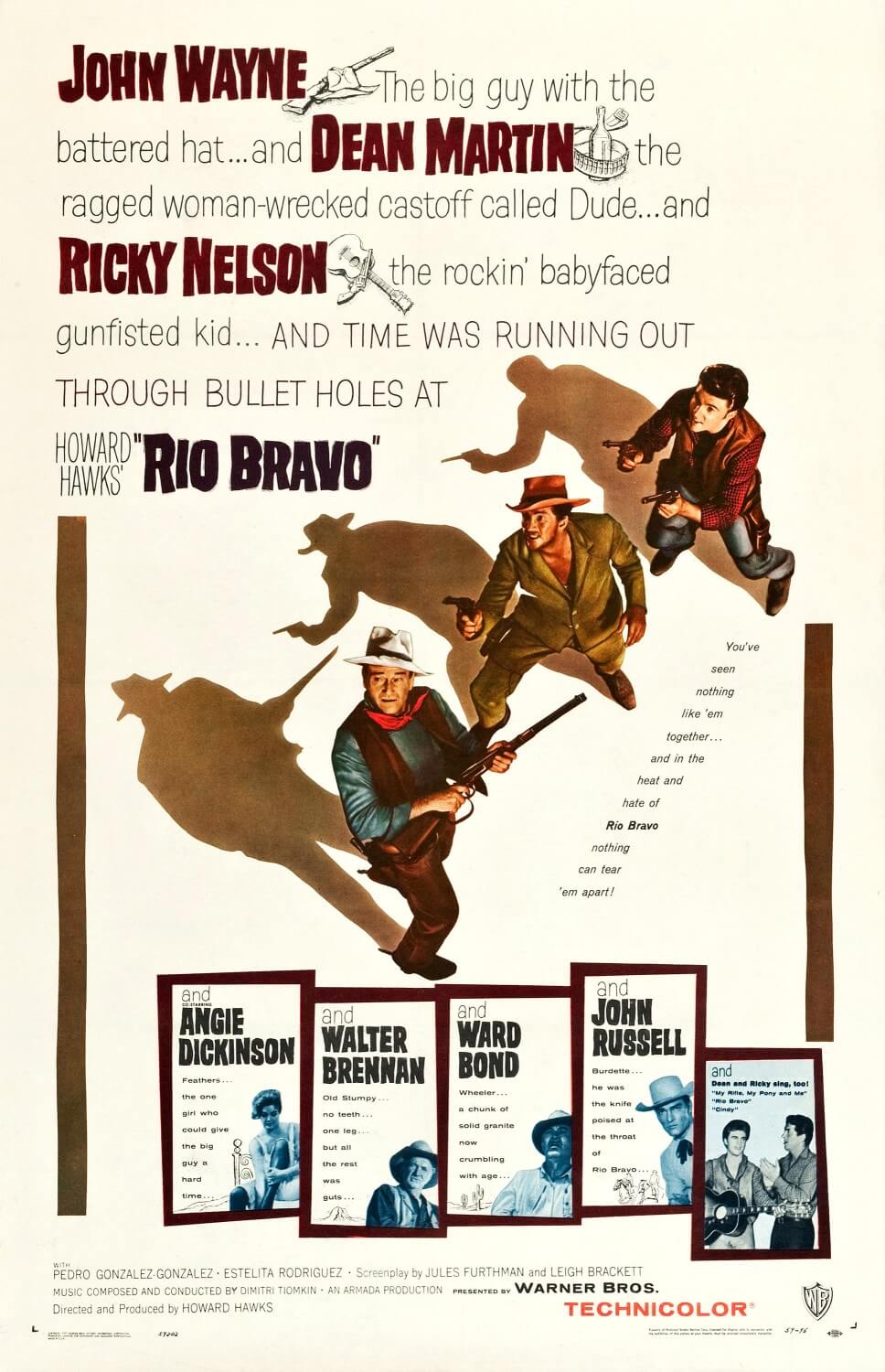

Rio Bravo (1959)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Few films have followed Western traditions with as much exhilarating craftsmanship, narrative and stylistic economy, or sheer escapist delight as Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo. The picture is a prescribed Western yarn in Hollywood terms, a familiar setup about a singular lawman taming the Old West, complete with shootouts, treacherous villains, and even twangy songs. Going further, the exceptional treatment represents a culmination of both Hawksian themes and techniques, as well as the indomitable screen presence of John Wayne’s heroic yet understatedly complex stature. Further still, Hawks and Wayne provide an antidote to the traditional Western archetype by creating a taut situation wherein the lone hero must reluctantly accept help from others, a support system in the form of a mismatched posse, to overcome an impossibly grim opposition. From start to finish, rich, intricate characters populate a fast-paced and flawlessly constructed motion picture, perhaps the most enjoyable and satisfying of its genre. And for another, but not last, hyperbolic statement about the film in this appreciation, British scholar Robin Wood remarked, “If I were asked to choose a film that would justify the existence of Hollywood, I think it would be Rio Bravo.”

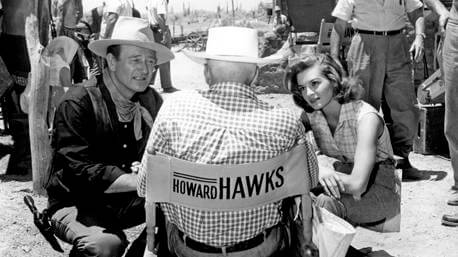

Over his 46-year career, from his 1926 debut in Hollywood to his final release in 1970, Howard Hawks worked for every major Hollywood studio and made pictures in every genre imaginable. Though the studio system had its limitations, Hawks’ range was boundless; he withstood the stifling factory mentality through his proficient skill and toughened approach. Although autueristic patterns can be found in Hawks’ body of work, he explored a prolific diversity of genres and, as author Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues notes, “produced in each one if not a masterpiece, then at least a great film.” He released the most scandalous gangster picture of its era, Scarface (1932); exemplary screwball comedies with Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940); the superb war films Sergeant York (1941) and Air Force (1943); an influential science-fictioner, The Thing from Another World (1951); and perhaps the most complicated mystery ever made, The Big Sleep (1946). But not until the 1950s, when French critics writing in the Cahiers du cinéma, most significantly Éric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette, reassessed his pictures, was his oeuvre championed. Once Rohmer and Rivette identified lasting motifs in his work, Hawks was recognized as an auteur whose range knew no limitations and seemed to transcend the expanse of Hollywood filmmaking. As Rohmer observed, “I don’t think that anyone can really love films without loving those of Howard Hawks.”

Hawks made Rio Bravo, his masterpiece among masterpieces, in 1958, after a nearly four-year hiatus following his only major critical failure and box-office bomb, the period epic Land of the Pharaohs (1955). Accustomed to releasing upwards of two or three pictures a year, his inactivity was uncharacteristic but necessary: He had no clear idea of how to follow up what was considered a monumental failure throughout the industry. In the interim, Hawks’ ego mended as he spent time in Europe, laboring over several unrealized projects. When he returned to Hollywood, he had a meeting with Jack Warner and explained he was anxious to begin work on a Western. At the time, Westerns were everywhere, and not just in cinemas, but on television as well (the number one show in America was Gunsmoke, after all). And what’s more, these weekly Western shows were about characters in the same way Hawks’ films were about characters instead of plots. Hawks’ successes in the genre with Red River (1948) and The Big Sky (1952) notwithstanding, Warner hesitated; the studio head was finally convinced when Hawks wrangled John Wayne to star. Wayne, who appeared in Red River, was in a slump and had done four films since Warner’s triumphant The Searchers in 1956, but none were Westerns and none very successful. For both actor and director, the proposed film would be a welcome return to familiar territory. (Hawks also considered casting Montgomery Clift for a full Red River reunion, but Clift’s moody acting style wouldn’t have fit the entertainer Hawks had planned.) Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman, who worked together on The Big Sleep, were enlisted to write. And with a budget of $1.9 million, Hawks delivered a picture that garnered $5.2 million in returns, the second-largest performer of his career after Sergeant York.

Hawks made Rio Bravo, his masterpiece among masterpieces, in 1958, after a nearly four-year hiatus following his only major critical failure and box-office bomb, the period epic Land of the Pharaohs (1955). Accustomed to releasing upwards of two or three pictures a year, his inactivity was uncharacteristic but necessary: He had no clear idea of how to follow up what was considered a monumental failure throughout the industry. In the interim, Hawks’ ego mended as he spent time in Europe, laboring over several unrealized projects. When he returned to Hollywood, he had a meeting with Jack Warner and explained he was anxious to begin work on a Western. At the time, Westerns were everywhere, and not just in cinemas, but on television as well (the number one show in America was Gunsmoke, after all). And what’s more, these weekly Western shows were about characters in the same way Hawks’ films were about characters instead of plots. Hawks’ successes in the genre with Red River (1948) and The Big Sky (1952) notwithstanding, Warner hesitated; the studio head was finally convinced when Hawks wrangled John Wayne to star. Wayne, who appeared in Red River, was in a slump and had done four films since Warner’s triumphant The Searchers in 1956, but none were Westerns and none very successful. For both actor and director, the proposed film would be a welcome return to familiar territory. (Hawks also considered casting Montgomery Clift for a full Red River reunion, but Clift’s moody acting style wouldn’t have fit the entertainer Hawks had planned.) Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman, who worked together on The Big Sleep, were enlisted to write. And with a budget of $1.9 million, Hawks delivered a picture that garnered $5.2 million in returns, the second-largest performer of his career after Sergeant York.

Hawks designed Rio Bravo as a response to director Fred Zinnemann and writer Carl Foreman’s High Noon (1952), a film he admired for its craft but despised for its story. In the film, Gary Cooper’s lone Marshal Will Kane faces certain death against a band of outlaws. He implores his cowardly townspeople to help him fight off the threat, but he fails to convince a single volunteer. He’s left to take down three nefarious outlaws single-handedly. High Noon‘s plot has been interpreted as a metaphoric left-wing attack on the era’s rampant McCarthyism. The small town so afraid to stand up for itself represents the American public’s fear of protesting against Joseph McCarthy. Its metaphoric implications aside, Hawks loathed the idea of a Western town in which its citizens refused to help, where its marshal feels so inadequate that he must plead with civilians for assistance. In turn, Hawks revealed that Rio Bravo would be his “right-wing answer” to Zinnemann’s picture. An outspoken Republican, he wanted to make a Western with a tough lawman who didn’t want help. And who was tougher than John Wayne? Sheriff John T. Chance, Wayne’s character in Rio Bravo, says of prospective volunteers, “If they’re really good, I’ll take them. If not, I’ll just have to take care of them.” Wayne called it “the John Wayne role” and felt the same way as Hawks about High Noon as his director. He told Roger Ebert, “What a piece of you-know-what that was… If I’d been the marshal, I would have been so goddamned disgusted with those chicken-livered yellow sons of bitches that I would have just taken my wife and saddled up and rode out of there.”

And yet, Rio Bravo is not a conservative film; rather, it does the opposite of what Hawks intended by proving to be a deftly humanist film. Sheriff Chance faces a fascist enemy, Nathan Burdette (John Russell), who expects the frontier to bow down to his elitist authority and wealth. When Nathan’s brother is jailed for murder, he hires countless thugs to intimidate and even kill anyone who helps the law until his brother is released. In response, the stubborn Chance reluctantly aligns with a chosen few to defeat Burdette, and through the course of the film, we realize he couldn’t have done it without them. Chance himself is a right-wing authority whose close-mindedness, if let alone, would lead to his own destruction. But he’s softened and supplemented by his friends, and as a result, his worldview is proven to be a deeply flawed outlook by the end. It’s hardly a rightist notion or narrative.

And yet, Rio Bravo is not a conservative film; rather, it does the opposite of what Hawks intended by proving to be a deftly humanist film. Sheriff Chance faces a fascist enemy, Nathan Burdette (John Russell), who expects the frontier to bow down to his elitist authority and wealth. When Nathan’s brother is jailed for murder, he hires countless thugs to intimidate and even kill anyone who helps the law until his brother is released. In response, the stubborn Chance reluctantly aligns with a chosen few to defeat Burdette, and through the course of the film, we realize he couldn’t have done it without them. Chance himself is a right-wing authority whose close-mindedness, if let alone, would lead to his own destruction. But he’s softened and supplemented by his friends, and as a result, his worldview is proven to be a deeply flawed outlook by the end. It’s hardly a rightist notion or narrative.

Few Hawks films could be reasonably argued as political; his films were about the joy of characters. More often than not, they were about men and male camaraderie unimpeded by, but interconnected with, a strong female presence. His resilient male characters bonded through conflict, while usually, a central, tomboyish woman remained one-of-the-boys, but she fell in love with the principal male role. Wood later isolated a more specific pattern in Hawks’ films, namely in Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and To Have and Have Not (1944), and along with Rio Bravo considered these a structural trilogy: each features a charismatic hero presiding over an all-male entourage; one of the hero’s followers is disabled or aged; though a villain or enemy exists in the film, the primary conflict revolves around a love interest; and this woman is self-reliant enough that she can survive without a man, until of course, she cannot. Of all Hawks’ films, Rio Bravo follows this structure most jealously.

The film opens with a dialogue-less sequence that, through an impressive shot economy on Hawks’ part, sets the stage for the ensuing film as a Silent Era picture might. Dressed in tatters and sweating for a drink, a former deputy-turned-alcoholic named Dude (Dean Martin), nicknamed Borrachón (“drunk” in Spanish), sneaks in the back door of a saloon in Rio Bravo, Texas. Joe Burdette (Claude Akins) notices Dude watching him pour a drink. Joe holds up a silver dollar, offering it to Dude, but then cruelly throws it into a spittoon. Desperate, Dude bends down to reach into the vat of spit (in a scene lifted from Josef von Sternberg’s Underworld, which Hawks co-wrote with Furthman, Ben Hecht, and others), but a foot quickly kicks the spittoon away. Dude looks up to see John T. Chance standing over him, looking down with disgust at the shamed Borrachón. Joe smiles, satisfied with his social authority. Chance walks over to confront him, but for his embarrassment, Dude clubs Chance from behind with some firewood. He tries to go after Joe too, but Burdette’s men hold Dude back, and Joe takes a few cheap shots. When a Good Samaritan tries to break up Dude’s beating, Joe shoots the unarmed man dead, point-blank, and then, unfazed, heads down the road to the Burdette’s saloon. A moment later, Chance follows, recovered from his blow, and speaks the first line. “Joe, you’re under arrest.” All at once, Chance is surrounded by Burdette’s armed men, who begin to move in. Dude comes up from behind once more, but this time takes a gun from one of the men’s holsters and shoots the pistol out of another man’s hand. He takes aim at a few others and tells Chance that he’s free to proceed. Chance knocks Joe out cold and, together, he and Dude drag Joe to the Sheriff’s Office.

By the next shot, some time has passed, and the following scenes establish Rio Bravo‘s pot-boiler setup. As a funeral procession marches through town for the man killed by Joe Burdette, local businessman Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond) returns with a wagon train of supplies, including fuel oil and boxes of dynamite, and finds Dude on guard on the outskirts of town. His deputy badge pinned back on after defending Chance in the bar, Dude orders Wheeler’s men, among them young gunslinger Colorado (Ricky Nelson), to remain outside of town until ordered otherwise. Chance explains to Wheeler that he has Nathan Burdette’s brother in jail, and Nathan has the town bottled-up tight—until Joe is set free, no help is getting in and Chance can’t transport Joe out. Wheeler asks Chance what kind of help he has, and Chance replies that along with Dude, he has Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a toothless old coot with a bum leg who guards the jail. “A lame-legged old man and a drunk,” Wheeler observes. “Is that all you’ve got?” Chance smiles and says, “That’s what I’ve got.” Had someone like Wheeler been Sheriff, he would’ve been more akin to Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane from High Noon, scouting the town for someone—anyone—to volunteer. When Wheeler suggests that Chance should ask for help, Chance replies: “Suppose I got ’em. What would I have? Some well-meaning amateurs, most of ’em worried about their wives and kids. Burdette has 30 or 40 men, all professionals. Only thing they’re worried about is earning their pay. No, Pat, all we’d be doing is giving them more targets to shoot at. A lot of people’d get hurt. Joe Burdette isn’t worth it. He isn’t worth one of those that’d get killed.” Despite Chance’s warnings, Wheeler goes about Rio Bravo and asks for help, and, for his good intentions, he ends up dead, shot by one of Burdette’s men. When Chance and Dude take down the shooter, they find a fifty-dollar gold piece on his body (“That’s just about what Burdette would figure a life is worth”). Now they’re all targets trapped inside Rio Bravo.

By the next shot, some time has passed, and the following scenes establish Rio Bravo‘s pot-boiler setup. As a funeral procession marches through town for the man killed by Joe Burdette, local businessman Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond) returns with a wagon train of supplies, including fuel oil and boxes of dynamite, and finds Dude on guard on the outskirts of town. His deputy badge pinned back on after defending Chance in the bar, Dude orders Wheeler’s men, among them young gunslinger Colorado (Ricky Nelson), to remain outside of town until ordered otherwise. Chance explains to Wheeler that he has Nathan Burdette’s brother in jail, and Nathan has the town bottled-up tight—until Joe is set free, no help is getting in and Chance can’t transport Joe out. Wheeler asks Chance what kind of help he has, and Chance replies that along with Dude, he has Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a toothless old coot with a bum leg who guards the jail. “A lame-legged old man and a drunk,” Wheeler observes. “Is that all you’ve got?” Chance smiles and says, “That’s what I’ve got.” Had someone like Wheeler been Sheriff, he would’ve been more akin to Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane from High Noon, scouting the town for someone—anyone—to volunteer. When Wheeler suggests that Chance should ask for help, Chance replies: “Suppose I got ’em. What would I have? Some well-meaning amateurs, most of ’em worried about their wives and kids. Burdette has 30 or 40 men, all professionals. Only thing they’re worried about is earning their pay. No, Pat, all we’d be doing is giving them more targets to shoot at. A lot of people’d get hurt. Joe Burdette isn’t worth it. He isn’t worth one of those that’d get killed.” Despite Chance’s warnings, Wheeler goes about Rio Bravo and asks for help, and, for his good intentions, he ends up dead, shot by one of Burdette’s men. When Chance and Dude take down the shooter, they find a fifty-dollar gold piece on his body (“That’s just about what Burdette would figure a life is worth”). Now they’re all targets trapped inside Rio Bravo.

However deadly and claustrophobic, the film’s setup allows the characters to develop in warm, unexpected ways, and through the danger, emphasizes the connections between Chance and his crew. For example, the sequence in which Dude and Chance track Wheeler’s assailant into the Burdette saloon is another masterful series of shots arranged by Hawks, but more significant is how it reestablishes Dude’s confidence. Dude became a drunk after a girl came through on the stagecoach, and before long, took Dude’s heart, and his sobriety, with her. Once a gifted sharpshooter, Dude’s hands now tremble from withdrawals, the strain always evident in his shifty posture or the way he can never roll a cigarette because of his shakes. But after a taste of law and order again in the bar, Dude’s friendship with Chance is reestablished, thus putting the Borrachón on the Burdettes’ hit list and giving Dude the impetus he needed to sober up. Dude’s dramatic arc consists of small personal victories offset by frequent reminders of his uneasy history with alcoholism. Among the most poignant occurs mid-film, after Dude takes a bath, shaves, and puts on new clothes. He returns to the jail afresh and, since he doesn’t look like his normal ragged self, Stumpy opens fire, believing Dude to be one of Burdette’s men. Dude’s shame is heartbreaking, his injury deep, but Chance refuses to coddle him. Even after issuing credit for Dude’s triumph in the bar, Chance cuts Dude down and never allows him to forget what he used to be. “You know one reason why you got by with it? They were laughin’ at you. Borrachón talkin’ big. You surprised ’em. The next time they’ll be ready for you.” Chance later defends his tough-love approach to Stumpy, warning that if he’s too supportive, then Dude might get too confident and fall to drink again. But Chance could also take his abuse too far, as Stumpy warns.

Dude’s sobriety and soul are on the line in nearly every scene, and before the film’s end, he comes close to returning to booze again. In one of the film’s most thrilling sequences, Burdette’s men capture Dude and corner Chance, but Colorado’s quick-draw saves them both. Since Dude fondly looks upon Colorado as a younger version of himself, his own failure in the situation is a painful reminder of what he’s become. Now Dude’s threat of self-annihilation reaches its height. Dude is determined to quit as a deputy and sits in the jailhouse, mulling over a bottle. He pours himself a shot, and, just as he’s about to drink, a song plays in the background. Nathan has hired a band to play “De Guello,” a mournful tune that General Santa Ana once ordered his men to play for the ill-fated Americans inside the Alamo. Nathan Burdette’s earlier line to Dude—”Every man should have a little power before he’s through”—resonates. At this, an aching reminder of Burdette’s power over the situation, Dude pours his shot back into the bottle, and he doesn’t spill a drop. His hands no longer shake. It’s a powerful moment, and Martin, who was not Hawks’ initial choice to play Dude, both astonishes and surprises in his performance. Another Rat-Packer, Frank Sinatra, topped Hawks’ list of candidates to play Dude (a list including James Cagney, John Cassavetes, Cary Grant, William Holden, Robert Mitchum, Spencer Tracy, and Richard Widmark). Hawks hired Martin after the crooner arrived at their initial early-morning meet after a night of hard work and drinking in Las Vegas; Martin was disheveled and hungover but chartered a plane and arrived on time. His initiative won Hawks over, and the resulting choice proved Martin’s finest, most tender screen performance.

Dude’s sobriety and soul are on the line in nearly every scene, and before the film’s end, he comes close to returning to booze again. In one of the film’s most thrilling sequences, Burdette’s men capture Dude and corner Chance, but Colorado’s quick-draw saves them both. Since Dude fondly looks upon Colorado as a younger version of himself, his own failure in the situation is a painful reminder of what he’s become. Now Dude’s threat of self-annihilation reaches its height. Dude is determined to quit as a deputy and sits in the jailhouse, mulling over a bottle. He pours himself a shot, and, just as he’s about to drink, a song plays in the background. Nathan has hired a band to play “De Guello,” a mournful tune that General Santa Ana once ordered his men to play for the ill-fated Americans inside the Alamo. Nathan Burdette’s earlier line to Dude—”Every man should have a little power before he’s through”—resonates. At this, an aching reminder of Burdette’s power over the situation, Dude pours his shot back into the bottle, and he doesn’t spill a drop. His hands no longer shake. It’s a powerful moment, and Martin, who was not Hawks’ initial choice to play Dude, both astonishes and surprises in his performance. Another Rat-Packer, Frank Sinatra, topped Hawks’ list of candidates to play Dude (a list including James Cagney, John Cassavetes, Cary Grant, William Holden, Robert Mitchum, Spencer Tracy, and Richard Widmark). Hawks hired Martin after the crooner arrived at their initial early-morning meet after a night of hard work and drinking in Las Vegas; Martin was disheveled and hungover but chartered a plane and arrived on time. His initiative won Hawks over, and the resulting choice proved Martin’s finest, most tender screen performance.

More important to Rio Bravo, more even than the sheriff “holding a bull by the tail” with the Burdettes, is the arrival of a superior challenge for Chance: a woman. When Chance delivers a package to local hotel owner Carlos (Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez), Carlos takes Chance upstairs to see the secret gift he ordered for his wife, Consuela (Estelita Rodriguez). “You, you do not have women, so you do not know,” Carlos says to Chance in a statement that tells us Chance is a longtime bachelor none-too versed in women. “But me, Carlos Robante, I know.” While searching for a towel to take a bath, a woman with a feather boa (Angie Dickinson) appears in the doorway and sees Carlos holding a pair of red ladies undergarments up to Chance’s waist. “Those things have great possibilities, but not for you,” she says coolly, the moment efficiently establishing her self-confident control and sexual experience, and based on Chance’s expression, his discomfort about women and embarrassment about sex. Feathers, as she’s later known, becomes an archetypal Hawksian woman, strong-willed and accustomed to dealing with men. She’s the type Hawks used before with Jean Arthur in Only Angels Have Wings, Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep and To Have and Have Not, Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby, and Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday. Feathers explains that she arrived on the stagecoach, not unlike Dude’s former lover, and perhaps this is why Chance goes out of his way to distrust her—he sees her as another woman just passing through. Moreover, based on a poster of a wanted gambler who’s been seen accompanied by a woman with feathers, he later suspects she’s a cheat and accuses her of taking aces out of a deck. She says that to prove it, he’ll have to search her. “Search you?” Chance says, shocked. She’s willing to let him, but she knows he won’t go through with it. “I think you’re embarrassed,” she remarks. Feathers knows her confident sexuality has given her control over Chance’s timidity, as he’s mistaken her for the wrong kind of woman.

For much of Rio Bravo, Chance tries to convince Feathers, and indeed himself, that he wants her to leave, but every encounter between the two ends up with Feathers in charge, and both of them a little more in love. He tells her to “quit playing cards, wearing feathers,” even after it’s determined that a card sharp has stolen the aces. She responds, “No, sheriff. No, I’m not going to do that. You see, that’s what I’d do if I were the kind of girl that you think I am.” Before long, Chance questions her about her past association with a wanted gambler, and she reveals that her former husband was shot when he cheated the wrong people. That Feathers continues to be who she is despite the protests of the man she loves makes her a commanding woman, and Chance gives in to her each night when he returns to Carlos’ hotel to sleep. At the hotel bar where Carlos has given her a job, Feathers offers Chance coffee, a meal, or a nightcap. “All I want is a drink,” he says. She responds, “Then ugh… This is all I can do for you?” in a statement pregnant with innuendo. Feathers has come on to Chance and come on to him strong, offering herself up readily. She tells him her bedroom door is open, should he want to use it; she tells him she’ll wait until this Burdette business is over, and then he can decide if he wants her. But Chance can barely return a kiss. Finally, she reaches out to him and plants one on his unmoving lips. “It’s even better when two people do it,” she says (recalling Bacall’s famous line to Bogie in To Have and Have Not: “It’s even better when you help.”). At every turn, Feathers’ presence softens Chance’s hardened exterior and, with her love, increases the stakes and leaves him, interestingly enough, more vulnerable to the Burdette threat.

For much of Rio Bravo, Chance tries to convince Feathers, and indeed himself, that he wants her to leave, but every encounter between the two ends up with Feathers in charge, and both of them a little more in love. He tells her to “quit playing cards, wearing feathers,” even after it’s determined that a card sharp has stolen the aces. She responds, “No, sheriff. No, I’m not going to do that. You see, that’s what I’d do if I were the kind of girl that you think I am.” Before long, Chance questions her about her past association with a wanted gambler, and she reveals that her former husband was shot when he cheated the wrong people. That Feathers continues to be who she is despite the protests of the man she loves makes her a commanding woman, and Chance gives in to her each night when he returns to Carlos’ hotel to sleep. At the hotel bar where Carlos has given her a job, Feathers offers Chance coffee, a meal, or a nightcap. “All I want is a drink,” he says. She responds, “Then ugh… This is all I can do for you?” in a statement pregnant with innuendo. Feathers has come on to Chance and come on to him strong, offering herself up readily. She tells him her bedroom door is open, should he want to use it; she tells him she’ll wait until this Burdette business is over, and then he can decide if he wants her. But Chance can barely return a kiss. Finally, she reaches out to him and plants one on his unmoving lips. “It’s even better when two people do it,” she says (recalling Bacall’s famous line to Bogie in To Have and Have Not: “It’s even better when you help.”). At every turn, Feathers’ presence softens Chance’s hardened exterior and, with her love, increases the stakes and leaves him, interestingly enough, more vulnerable to the Burdette threat.

Fortunately, Chance has plenty of friends in his corner, aside from Feathers and Dude, that is. Take the talented 17-year-old gunslinger, Colorado, who Ricky Nelson plays with cool composure, and who Chance admires for having the “good sense” not to join him at first. Throughout the film, Colorado downplays his own talent and participation. And yet, he’s a not-inconsiderable force in the action who conversely demands acknowledgment from the start. When Wheeler’s wagon train first rolls into town, Colorado rides guard alongside his employer. Chance asks Wheeler who the boy is, and Colorado says, “I speak English, Sheriff. You wanna ask me.” Chance doesn’t mind Colorado’s insistence and, in fact, much like Dude, who keeps a careful eye on Colorado during this exchange, admires the boy. Chance knows he’s “so good he doesn’t feel he has to prove it”—a commendably divergent notion to most young gunslingers desperate to make a name for themselves. What’s more, whereas Chance is a veritable dunce with women, quite comically so, Colorado seems at ease with them, despite being a teenager. He seems to know what Feathers’ wants from Chance and helps him along. When it’s discovered that Feathers was not to blame for stealing the aces from the deck, Colorado reminds Chance of Feathers’ due apology: “Aren’t you forgetting something, Sheriff?” Nelson was also Hawks’ answer to the studio’s concerns about box-office performance. Son of Ozzie Nelson, Ricky had become a household name with his appearances on the television show The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet (1952-1966), and his successful string of rock‘n’roll hits. Nelson’s standout moment in the film comes after Dude is captured and three of Burdette’s men corner Chance. Colorado quickly assesses the situation, instructs Feathers to throw a flower pot through a window at just the right moment, and when she does, he tosses Chance a rifle (in a sequence inspired by an analogous one in Red River), and together he and Chance take the three men down. Through split-second timing both onscreen and in the editing room, it’s among Rio Bravo’s most breathless sequences.

By contrast, Stumpy is an irascible codger present largely, but not entirely, for comic relief. It almost goes without saying that Hawks cast Walter Brennan as Stumpy. The director and actor had collaborated five times before, and Brennan’s folksy quality had made him the preeminent old-timer in Westerns for directors John Ford, William Wyler, Anthony Mann, and others. More recently, Brennan had been starring in the television series The Real McCoys (1957-1963), and Hawks had to push the actor harder than ever before to perform in a style suitable for film. Still, after their previous partnership for a similar role in Red River, Brennan arrived on-set and asked “In or out?” about his dentures; the answer—out—leaves Brennan’s character toothless, crabby, and never knowing when to shut up. When Dude almost loses his head to Stumpy’s shotgun after a bath and a shave, Stumpy keeps reminding Dude, “You, you been going around here the past couple of years like somethin’ the cat dragged in” until Dude snaps from wounded pride—”Just shut up!” Chance’s only enduring friend, Stumpy, takes constant abuse from him. Lines like “Never can please ya'” and “Nothin’s ever good enough” pour out of Stumpy’s empty mouth with cantankerous humor. He and Chance bicker like an old married couple in that charming, Hawksian way. But Rio Bravo leaves no character as a one-note construction; even Stumpy has his dramatic turn when Nathan Burdette visits his brother in jail. Brennan delivers a quick line that never needs further explication in the film, yet adds incredible gradation onto Stumpy: “Four hundred and sixty acres might be little to you, Nathan, but it was a lot of country to me.”

By contrast, Stumpy is an irascible codger present largely, but not entirely, for comic relief. It almost goes without saying that Hawks cast Walter Brennan as Stumpy. The director and actor had collaborated five times before, and Brennan’s folksy quality had made him the preeminent old-timer in Westerns for directors John Ford, William Wyler, Anthony Mann, and others. More recently, Brennan had been starring in the television series The Real McCoys (1957-1963), and Hawks had to push the actor harder than ever before to perform in a style suitable for film. Still, after their previous partnership for a similar role in Red River, Brennan arrived on-set and asked “In or out?” about his dentures; the answer—out—leaves Brennan’s character toothless, crabby, and never knowing when to shut up. When Dude almost loses his head to Stumpy’s shotgun after a bath and a shave, Stumpy keeps reminding Dude, “You, you been going around here the past couple of years like somethin’ the cat dragged in” until Dude snaps from wounded pride—”Just shut up!” Chance’s only enduring friend, Stumpy, takes constant abuse from him. Lines like “Never can please ya'” and “Nothin’s ever good enough” pour out of Stumpy’s empty mouth with cantankerous humor. He and Chance bicker like an old married couple in that charming, Hawksian way. But Rio Bravo leaves no character as a one-note construction; even Stumpy has his dramatic turn when Nathan Burdette visits his brother in jail. Brennan delivers a quick line that never needs further explication in the film, yet adds incredible gradation onto Stumpy: “Four hundred and sixty acres might be little to you, Nathan, but it was a lot of country to me.”

Each of the afore-described characters has a quality of openness, a willingness to discuss their anxieties, and that brings something out in John T. Chance—he feels an almost parental concern for Dude, vulnerability around Feathers, admiration for Colorado, and a lightheartedness around Stumpy. And Rio Bravo is a richer experience for the diversity of personalities onscreen. Without them, Chance’s pronounced character flaws would be untenable for an audience; after all, Wayne’s character is an obstinate, judgmental, and suspicious sort. He cuts down everyone around him by pointing out their imperfections, some of his remarks playful jabs and others quite serious, while rarely openly acknowledging his own flaws. And it’s ironic how Chance’s refusal to accept help from the townsfolk to fight Nathan Burdette, the characteristic Hawks used to establish him as disparate to High Noon‘s marshal, curiously becomes a failing that almost gets him killed. Fortunately, Feathers throws a pot, and Colorado decides to get involved; otherwise, Chance would have given up to Burdette’s three armed men who cornered him, walked them down to the jailhouse, and probably died in the process. But once Colorado finally resolves to join Chance’s crew after saving his life, and in that making himself a target for Burdette, Chance spurns Colorado for not joining earlier.

Chance’s flaws are mended in comic scenes. A late scene shows Chance’s sense of humor when Stumpy prattles on about being unappreciated for his housekeeping in the jail (“Not even a thank you do I get!”) and Chance chimes in, “Maybe you’re right, Stumpy, you’re a treasure. I don’t know what I’d do without you.” Chance quickly smooches Stumpy atop his head and makes for the door, and Stumpy thwacks Chance on his bottom with a broom as Chance scurries outside, the scene like something out of a slapstick comedy. Underneath Chance’s fortified exterior rests a man who struggles to express emotion. Some of Wayne’s best moments in the film involve Chance’s proud smiles at his friends, when he sits back and observes. About his own approach to his performance, Wayne admitted, “I don’t act, I react,” and that philosophy embodies both Wayne and Chance.

As Chance and Feathers come to a romantic understanding and the worst of Dude’s withdrawal symptoms pass, Rio Bravo‘s mature personal conflicts resolve themselves before the climactic battle with the Burdettes, and the film’s emphasis on characters over Western action leaves the climax feeling almost like an afterthought, structurally anyway. As a result, the showdown with the Burdettes has to deliver a big enough wallop to counteract the emotional resolutions that have already occurred. What else but dynamite could pack such a punch? Dude is captured by Burdette’s men just before the finale, and they arrange a prisoner exchange for Joe at the Burdette warehouse. Chance and Colorado arm themselves and take a position in some rundown brick shacks opposite the Burdettes. Left behind, Stumpy arrives after the shooting begins, and together with Chance, comes up with a last-minute bright idea: he tosses Wheeler’s dynamite, which has been stored near the Burdettes’ warehouse since the film’s beginning, and Chance shoots it for a thunderous explosion. After a few makeshift grenades detonate, the Burdettes surrender.

As Chance and Feathers come to a romantic understanding and the worst of Dude’s withdrawal symptoms pass, Rio Bravo‘s mature personal conflicts resolve themselves before the climactic battle with the Burdettes, and the film’s emphasis on characters over Western action leaves the climax feeling almost like an afterthought, structurally anyway. As a result, the showdown with the Burdettes has to deliver a big enough wallop to counteract the emotional resolutions that have already occurred. What else but dynamite could pack such a punch? Dude is captured by Burdette’s men just before the finale, and they arrange a prisoner exchange for Joe at the Burdette warehouse. Chance and Colorado arm themselves and take a position in some rundown brick shacks opposite the Burdettes. Left behind, Stumpy arrives after the shooting begins, and together with Chance, comes up with a last-minute bright idea: he tosses Wheeler’s dynamite, which has been stored near the Burdettes’ warehouse since the film’s beginning, and Chance shoots it for a thunderous explosion. After a few makeshift grenades detonate, the Burdettes surrender.

Now all is well in Rio Bravo, and the film returns to the characters again. The final scene finds Chance in Feathers’ room, looking over her new outfit—a tight, black getup she plans to wear while singing in Carlos’ hotel. Rather than scorn her, Chance says he’ll arrest her if she wears “a rig like that” in public. Feathers weeps with joy; it means Chance loves her, that he doesn’t want anyone but himself to see her wearing such things. In the end, Feathers changes into a robe, and Chance tosses the tights out the window for the patrolling Dude and Stumpy to find, consummation implied and inevitable. And with this, Hawks completes what his biographer Todd McCarthy called an ultimate “adolescent adventure” of boyish friendships, escapism, and romance.

If any moment in Rio Bravo has been called out of place more than others, it’s during a calm-before-the-storm sequence when the film’s musical interlude allows Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson to perform—a sequence that is nonetheless the film’s purest display of male camaraderie. Hawks felt he had to include songs by the two popular musicians in his cast, no matter how obvious a commercial-minded choice it may have been. The scene opens in the jailhouse as Dude, resting on a cot with his hat pulled over his eyes, sings “My Rifle, My Pony, and Me,” a ballad written by composer Dimitri Tiomkin and Paul Francis Webster from Tiomkin’s original theme to Red River. Colorado harmonizes for Dude in the song, and then himself segues into the livelier “Cindy” with background vocals by Dude and harmonica accompaniment courtesy of Stumpy. Chance just stands back with a cup of coffee, smiling, watching the show, as we do. Nelson and Martin recorded the songs at Capitol Records along with the titular theme “Rio Bravo” that plays over the end credits (and another song called “Restless Kid” written by Johnny Cash for Nelson, but it didn’t make it into the final film). While the songs provide a needed reprieve from the tension and further the bond between these men, they’re also a constant reminder of the stakes. When the band plays “De Guello,” and it echoes through the town, it haunts our heroes. The original “De Guello” played at the Alamo was rewritten for the film; Tiomkin and Hawks felt the original song lacked a cinematic quality, and so Tiomkin rewrote it. Wayne liked Tiomkin’s version so much that he used it in his directorial debut, The Alamo (1960), and so Wayne’s film features a General Santa Ana who orders his men to play a piece written for a Hollywood motion picture from 1959.

Intriguingly, Hawks did not make the right-wing film he intended, but rather one that presents its right-wing hero in a negative light next to his more sympathetic, leftist friends. Chance is a man who, according to Hawks’ understanding of and intent for the film as a reaction to High Noon, doesn’t need any help. And yet, Chance has no less than five characters to provide him with assistance: Stumpy, Dude, Colorado, Feathers, and later Carlos, who arrives at the final shootout with rifle shells. One could argue that, due to the closeness of these friends and their mutual intimacies, Chance, in point of fact, requires more help than Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane, who called for strength in numbers and not necessarily emotional support. As a hero, Chance is less sympathetic than, say, Dude and Feathers, who acknowledge their vulnerabilities. The audience sympathizes more with Dude and Feathers because they are morally correct and open-minded. By contrast, Chance represents the only reactionary and conservative figure in a film intended to be an antithesis to Zinneman’s supposed left-wing agenda. Chance’s dogged resolutions are nothing less than extreme and violent, from beating liars to throwing dynamite in the climax. But the outcome remains satisfying guiltily since Chance should know better; he’s fighting the Burdettes’ brand of fire with his own, while Dude and Feathers stand by (and participate) with equal measures of awe and revulsion at Chance’s methods. This morality shifts the film away from a mere right-wing exposé and into a more entangled character study. Although Hawks failed to achieve what he set out to do in terms of his response to High Noon, not every artist understands the levels of implication embedded into their own work, and perhaps Rio Bravo is one of those instances.

Intriguingly, Hawks did not make the right-wing film he intended, but rather one that presents its right-wing hero in a negative light next to his more sympathetic, leftist friends. Chance is a man who, according to Hawks’ understanding of and intent for the film as a reaction to High Noon, doesn’t need any help. And yet, Chance has no less than five characters to provide him with assistance: Stumpy, Dude, Colorado, Feathers, and later Carlos, who arrives at the final shootout with rifle shells. One could argue that, due to the closeness of these friends and their mutual intimacies, Chance, in point of fact, requires more help than Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane, who called for strength in numbers and not necessarily emotional support. As a hero, Chance is less sympathetic than, say, Dude and Feathers, who acknowledge their vulnerabilities. The audience sympathizes more with Dude and Feathers because they are morally correct and open-minded. By contrast, Chance represents the only reactionary and conservative figure in a film intended to be an antithesis to Zinneman’s supposed left-wing agenda. Chance’s dogged resolutions are nothing less than extreme and violent, from beating liars to throwing dynamite in the climax. But the outcome remains satisfying guiltily since Chance should know better; he’s fighting the Burdettes’ brand of fire with his own, while Dude and Feathers stand by (and participate) with equal measures of awe and revulsion at Chance’s methods. This morality shifts the film away from a mere right-wing exposé and into a more entangled character study. Although Hawks failed to achieve what he set out to do in terms of his response to High Noon, not every artist understands the levels of implication embedded into their own work, and perhaps Rio Bravo is one of those instances.

Nevertheless, the resulting film tangles its characters in perilous physical and intricate psychological situations, all with a conversely measured pace and gradual development over a joyfully protracted runtime. Jean-Luc Godard noted that Rio Bravo “is a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception, but Hawks has made his film so that the insight can pass unnoticed… fitting all that he holds most dear into a well-worn subject.” The film’s situations became so appealing to Hawks that he used leftover ideas from the Brackett-Furthman treatment when he essentially remade Rio Bravo in 1966 with El Dorado. Though El Dorado would prove a lesser film by far, Hawks’ trend of self-reflexive filmmaking had long been a staple of his, from standardized Hawksian character traits to the spittoon sequence from Underworld, from Feathers’ dialogue borrowed from To Have and Have Not to the music and action scenes repeated from Red River. Other filmmakers were equally inspired by Rio Bravo‘s tense set of circumstances; John Carpenter later borrowed the basic setup for Assault on Precinct 13 (1977) and again on Ghosts of Mars (2001). And while at first glance Rio Bravo is simply a crowd-pleasing effort, it misleads the viewer with its accessibility and, in truth, requires much participation from the viewer. Wood writes, “The ideal Hawks spectator is intelligent, alert and responsive.” One must be a receiver to his character dynamics and slick technical filmmaking, all drawn from Hawks’ body of work and converging into a singular filmic tome. As the culmination of Hawks’ skill and trademarks, Rio Bravo affirms the director’s craft as boundless, invariably complex, and ceaselessly entertaining, and the film itself stands as an unrivaled Western milestone.

Bibliography:

Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Devil Made It. New York: Alfred A.Knopf, 1997.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

McCarthy, Todd. Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

Wood, Robin. Rio Bravo. (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, 2003.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review