The Definitives

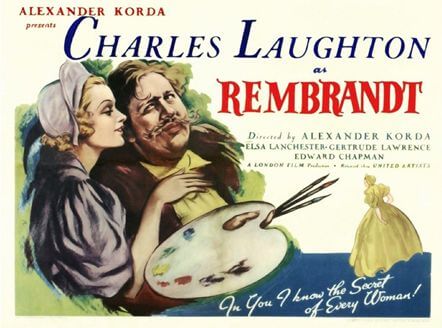

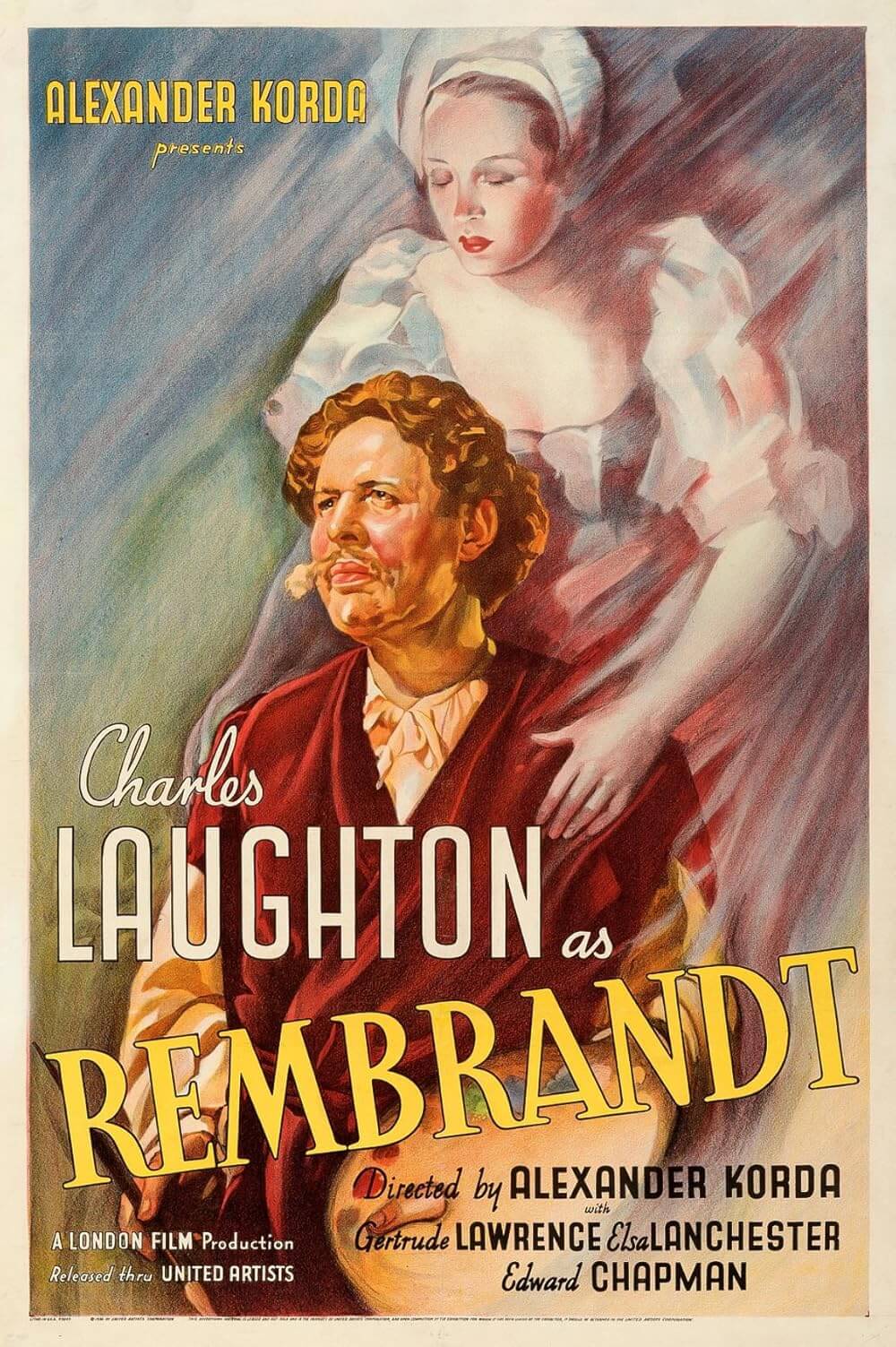

Rembrandt

Essay by Brian Eggert |

When unveiled to its patrons in the civic militia guard, Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Night Watch receives scolding laughter and protests that noblemen were depicted so shamefully, that several of the portraits therein appear shrouded by shadow, that the darkness of the work spreads a sense of confusion about its composition. This is not the traditionalized representation that the painter was commissioned for. In defense of his work, the Dutch painter, played by Charles Laughton, reproaches Captain Banning Cocq and his company for hiding beneath a veneer of fancy hats and elaborate uniforms, declaring that he painted what he saw. “I wasn’t trying to paint gentlemen of rank and position,” says Rembrandt. “I wanted to paint men. Soldiers. Company marching out… Gentlemen of rank and position, indeed.” He takes the feather-topped hat from Banning Cocq’s head. “Here’s your gentlemen of rank, and what’s underneath it?” Rembrandt begins pointing at the company’s men before him. “Your nose is painted by bad liquor. Your mouth is reeking with bawdy kisses. Vanity and stupidity are written all over your face. The only pretty thing about you are your ruffs and your breastplates. And the only distinguished thing about you are your hats.”

Alexander Korda’s film Rembrandt provides a parallel between its topic and presentation, in that both the motion picture and the painter sought to humanize their subjects. Released in 1936, the production sets aside the typical birth-life-death formula found in countless movie biographies, and instead examines how the man’s individualism spread among his life and work. It does not seek to give term paper facts such as precise dates, or catalog the names of Rembrandt’s most famous paintings and etchings. It provides a cinematic explanation as to why Rembrandt chose to represent time-honored motifs, such as religious and historical figures, as beggars and prostitutes, and how he could portray a face with such insight. Korda makes it so even those unfamiliar with the painter’s history can understand his conceptual approach.

The film opens where Rembrandt’s financial success began to falter. But prior to this, he painted conventional themes in an orthodox style. Born in 1606 in Leyden, the Netherlands, he was classically trained for historical painting at the local university. His works from this time appeared no different than dozens of his fellow painters, rendering idealized images in their correct, if romanticized glory with fine, invisible brushstrokes. Aside from a wily twinkle in the eyes of his portraits, there was little to distinguish Rembrandt’s work from his contemporaries. After moving to Amsterdam, he took pupils such as Gerrit Dou and earned large commissions, making a name for himself as a portrait painter. But his true intent could be discovered in his etchings, which embraced a more casual, interpretive method that used stylization to capture imperfection.

The film opens where Rembrandt’s financial success began to falter. But prior to this, he painted conventional themes in an orthodox style. Born in 1606 in Leyden, the Netherlands, he was classically trained for historical painting at the local university. His works from this time appeared no different than dozens of his fellow painters, rendering idealized images in their correct, if romanticized glory with fine, invisible brushstrokes. Aside from a wily twinkle in the eyes of his portraits, there was little to distinguish Rembrandt’s work from his contemporaries. After moving to Amsterdam, he took pupils such as Gerrit Dou and earned large commissions, making a name for himself as a portrait painter. But his true intent could be discovered in his etchings, which embraced a more casual, interpretive method that used stylization to capture imperfection.

Rembrandt rebelled against the institution of classical painting by eventually refusing to idealize the body. He begins by painting the elderly and obese, showing them with wrinkles and large stomachs, hardly in the flattering and edited fashion that he was taught. Consider Rembrandt’s nudes, which transcend the concepts of “Nude” and “Naked” entirely. “Nudes” offer classical and idealizations, such as the emblematic sex object Venus, who often covers her modesty while she beckons viewers. Whereas “Naked” suggests that being unclothed is shameful, ugly, and related to Original Sin, and censures the viewer for looking. Rembrandt transcends these definitions in his unclothed figures by depicting them exaggerated and unattractive, but describing them in poses otherwise reserved for sexually alluring subjects. They are frequently modeled from repellent prostitutes, the only persons who would stand nude for an artist in Rembrandt’s time. By representing unsightly characters, he seems to signify that the body will eventually fail, reminding viewers of our humanity and evoking a realization that standard painting are illusions.

Something beautiful and true exists in Rembrandt’s lifelong opus of self-portraiture, and in his later work of pickpockets, street walkers, and vagabonds. He does not seek to hide his brushstrokes late in life; likewise, the details of his etchings emerge out of a disorganized scribbling that feels quickly assembled, but visionary in the serenity of their end result. He wants flaws acknowledged both in theme and method, for the viewer to see how the picture came about, and know that the image is a construct, because for Rembrandt, defects and the layers that make up an individual denote humanity. And somewhere inside our humanity resides our truth. Kings are not merely a crown, but also men who can lament and bear a heavy brow. A company of militia is not just a series of dutiful uniforms, but men with inherent shortcomings and blemishes.

Something beautiful and true exists in Rembrandt’s lifelong opus of self-portraiture, and in his later work of pickpockets, street walkers, and vagabonds. He does not seek to hide his brushstrokes late in life; likewise, the details of his etchings emerge out of a disorganized scribbling that feels quickly assembled, but visionary in the serenity of their end result. He wants flaws acknowledged both in theme and method, for the viewer to see how the picture came about, and know that the image is a construct, because for Rembrandt, defects and the layers that make up an individual denote humanity. And somewhere inside our humanity resides our truth. Kings are not merely a crown, but also men who can lament and bear a heavy brow. A company of militia is not just a series of dutiful uniforms, but men with inherent shortcomings and blemishes.

Herein resides the triumph of Korda’s film, which does not fritter away screen time on Rembrandt’s uncharacteristic early years, when his paintings were no more individualistic than a math student’s correct answers next to his peer’s. In form-follows-function manner, Korda’s film begins in 1642 with the death of Rembrandt’s wife Saskia, the rejection of The Night Watch,and the lasting period of financial troubles for the painter. During this time, Rembrandt identifies most with the human side of his subjects, as filing bankruptcy suddenly makes food and painting supplies scarce and creditors cruel. He spends time with tramps to understand their lifestyle, and then represents them in his work. In one scene, Rembrandt pays a beggar, played by an almost unrecognizable Roger Livesey, to pose for a portrait as a king. In return, the hobo offers to show his employer lessons on how to beg, a skill Rembrandt will need in the future.

Laughton plays Rembrandt with that larger than life quality that realized cinema’s finest Captain Bligh, Henry VIII, and Quasimodo, but also considerable pathos. Laughton plunged himself into his character, buying rare prints of Rembrandt etchings, researching the artist’s painting method, and even visiting Holland to immerse himself in the setting. Though, few of the factual details served Laughton with a better understanding of the script beyond a background to his role; the titles and technical fine points behind Rembrandt’s work were left out of the writing, since Korda concerned himself more with the emotional resonance of his screen story. Always demanding on set, Laughton insisted Elsa Lanchester, his wife who starred in Bride of Frankenstein the previous year, play the crucial role of Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s lover. He inflamed tantrums on the set and caused production to slow. But this was usual for Laughton.

Korda, who partnered with Laughton previously in 1933 on The Private Life of Henry VIII, knew tolerating the actor’s behavior would pay off in the final performance. How right he was. Laughton’s busy hands and eyes create an observant, thoughtful character driven by his own virtue and desire to see the reality of people, and consequently imply the fantasy of then-modern painting. Laughton stokes his moustache and quotes biblical verse with grave tongue to lend his character touching, human airs. His eyes look back and forth, as if at all times assessing the situation around him. He is bold yet timid and modest, as only a poor but gifted genius could be. And in the final scenes in the year of Rembrandt’s death, Laughton’s rigid, squinty-eyed portrayal, ripened by a wry and knowing smile, recalls with uncanny accuracy the substance from so many late-life self-portraits by the Dutch master.

Korda, who partnered with Laughton previously in 1933 on The Private Life of Henry VIII, knew tolerating the actor’s behavior would pay off in the final performance. How right he was. Laughton’s busy hands and eyes create an observant, thoughtful character driven by his own virtue and desire to see the reality of people, and consequently imply the fantasy of then-modern painting. Laughton stokes his moustache and quotes biblical verse with grave tongue to lend his character touching, human airs. His eyes look back and forth, as if at all times assessing the situation around him. He is bold yet timid and modest, as only a poor but gifted genius could be. And in the final scenes in the year of Rembrandt’s death, Laughton’s rigid, squinty-eyed portrayal, ripened by a wry and knowing smile, recalls with uncanny accuracy the substance from so many late-life self-portraits by the Dutch master.

In the film’s most powerful scenes, Rembrandt leaves the cruel city of Amsterdam, which has discarded his reputation and left him destitute. He travels to Leyden by foot and arrives at his family’s mill to a welcoming father and brother, peasant bread and hot soup. He feels at home, even at peace. That evening he visits the local pub, hoping to find his place in the world. Local peasants recognize him, but they accuse him of thinking himself too good for their small village. Why doesn’t he go back to the city, where he belongs? A barroom brawl breaks out. The next morning, Rembrandt tries to work alongside his father and brother at the mill, but finds physical labor out of his range. If not at the burgeoning art centre of Amsterdam, and not at his birthplace, where does Rembrandt belong? Categorizing his artwork comes with the same difficulty. Rembrandt did not paint in the style of his contemporaries, but rather innovated from masters like Titian and invented his own approach. But his advances did not stir his generation or the subsequent one to follow his lead. As the film illustrates, Rembrandt belongs nowhere, and therefore he must be considered a radical among a crowd of rigidly instructed artisans taught to compose art in a particular way. Korda recognizes this and chooses to make his film, which runs a meager 85-minutes, into a concise and spirited reading. Within the film’s short length, he communicates the distinctiveness of Rembrandt’s painterly persona and how his work is remembered because of it, without squandering time on pointless biographical facets.

It would be easy to condemn Rembrandt for its historical inaccuracies or brevity in places, except that registering the painter’s entire life is not Korda’s concern. The film makes no mention of Rembrandt’s three lost children before Saskia bore his son, Titus, played by John Bryning. In fact, Saskia never appears onscreen. Nor does the film suggest that the painter was perhaps Jewish, which is a growing belief among art historians. It fails to mention how Rembrandt tries to commit his housekeeper and lover, Geertje Dirx (stage actress Gertrude Lawrence), to an asylum after their falling out. And no discussion ensues about Rembrandt’s own excessive art collecting, how he purchased drawings and paintings from his Italian predecessors, such as Raphael, or secretly bid on his own work to increase its value.

It would be easy to condemn Rembrandt for its historical inaccuracies or brevity in places, except that registering the painter’s entire life is not Korda’s concern. The film makes no mention of Rembrandt’s three lost children before Saskia bore his son, Titus, played by John Bryning. In fact, Saskia never appears onscreen. Nor does the film suggest that the painter was perhaps Jewish, which is a growing belief among art historians. It fails to mention how Rembrandt tries to commit his housekeeper and lover, Geertje Dirx (stage actress Gertrude Lawrence), to an asylum after their falling out. And no discussion ensues about Rembrandt’s own excessive art collecting, how he purchased drawings and paintings from his Italian predecessors, such as Raphael, or secretly bid on his own work to increase its value.

The film does focus on Rembrandt’s financial situation, however, examining how, after filing bankruptcy, any completed pieces became the property of the courts to pay his creditors. How can a painter motivate himself to paint when the end product is not his own to sell? It serves less as a form of expression then, and more as a unit of exchange. What artist can find inspiration in that? In a clever move, Hendrickje and Titus become his employers, art dealers who acquire paintings and etchings as payment for room and board to circumvent the courts. This is done to support their lifestyle, of course, but more so to give Rembrandt reason to keep creating for himself, as without his art he could not survive. Such a conflict defines the very core of Rembrandt’s work. In his time, art was more of a business than a form of personal liberation, similar to how hordes carpenters or textile workers were clumped into guilds. But Rembrandt symbolizes a modern approach to creating art, making it not a craft to be mastered and sold, but an act of individualism and expression.

In 1932, Alexander Korda founded London Films in Britain with his younger brothers Zoltan and Vincent. He made his name through sumptuous costume dramas, pictures about what historical figures were like behind their bedroom doors. He went on to produce Carol Reed’s The Third Man and The Fallen Idol, and Olivier’s version of Richard III, eventually earning the first directorial Knighthood for his contributions to British cinema. From dazzling costumes to elaborate sets designed by Vincent, who won an Oscar for his toils on Thief of Bagdad from 1940, no expense was spared on visuals. But titles like The Private Life of Don Juan and That Hamilton Woman dwell on the humanity of their distinguished parties, not the lavish ornamentation that surrounds them. Never does Korda stand in awe of his characters’ riches, only his characters. He frames them in a way that personalizes the drama, seeing them as people and not dry historical curiosities. Rembrandt diverts from Korda’s usual grand, extravagant production method, and instead tells a small-scale story rooted in humanistic drama, as if one of Rembrandt’s own paintings had come to life onscreen. Vincent Korda’s sets are impressive but not imposing; he constructs Amsterdam miniatures and a staggering windmill that disappear into the landscape, a testament to their flawless construction. Even cinematographer Georges Périnal employs high contrast lighting and earthy shadows to tell the story, akin to how Rembrandt himself might have described it. Here is one of the great filmic biographies, designed in every way to facilitate a conceptual consciousness of Rembrandt’s artwork, free of academic facts and forced reenactments of momentous scenes in the artist’s life. Through it, Korda instills an understanding of what made Rembrandt and his art great, and allows the textbooks to fill in the blanks.

In 1932, Alexander Korda founded London Films in Britain with his younger brothers Zoltan and Vincent. He made his name through sumptuous costume dramas, pictures about what historical figures were like behind their bedroom doors. He went on to produce Carol Reed’s The Third Man and The Fallen Idol, and Olivier’s version of Richard III, eventually earning the first directorial Knighthood for his contributions to British cinema. From dazzling costumes to elaborate sets designed by Vincent, who won an Oscar for his toils on Thief of Bagdad from 1940, no expense was spared on visuals. But titles like The Private Life of Don Juan and That Hamilton Woman dwell on the humanity of their distinguished parties, not the lavish ornamentation that surrounds them. Never does Korda stand in awe of his characters’ riches, only his characters. He frames them in a way that personalizes the drama, seeing them as people and not dry historical curiosities. Rembrandt diverts from Korda’s usual grand, extravagant production method, and instead tells a small-scale story rooted in humanistic drama, as if one of Rembrandt’s own paintings had come to life onscreen. Vincent Korda’s sets are impressive but not imposing; he constructs Amsterdam miniatures and a staggering windmill that disappear into the landscape, a testament to their flawless construction. Even cinematographer Georges Périnal employs high contrast lighting and earthy shadows to tell the story, akin to how Rembrandt himself might have described it. Here is one of the great filmic biographies, designed in every way to facilitate a conceptual consciousness of Rembrandt’s artwork, free of academic facts and forced reenactments of momentous scenes in the artist’s life. Through it, Korda instills an understanding of what made Rembrandt and his art great, and allows the textbooks to fill in the blanks.

Bibliography:

Drazin, Charles. Korda: Britain’s Only Movie Mogul. Sidgwick & Jackson, 2002.

Schama, Simon. Rembrandt’s Eyes. New York: Knopf, 1999.

Westermann, Mariët. Rembrandt. London: Phaidon, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review