The Definitives

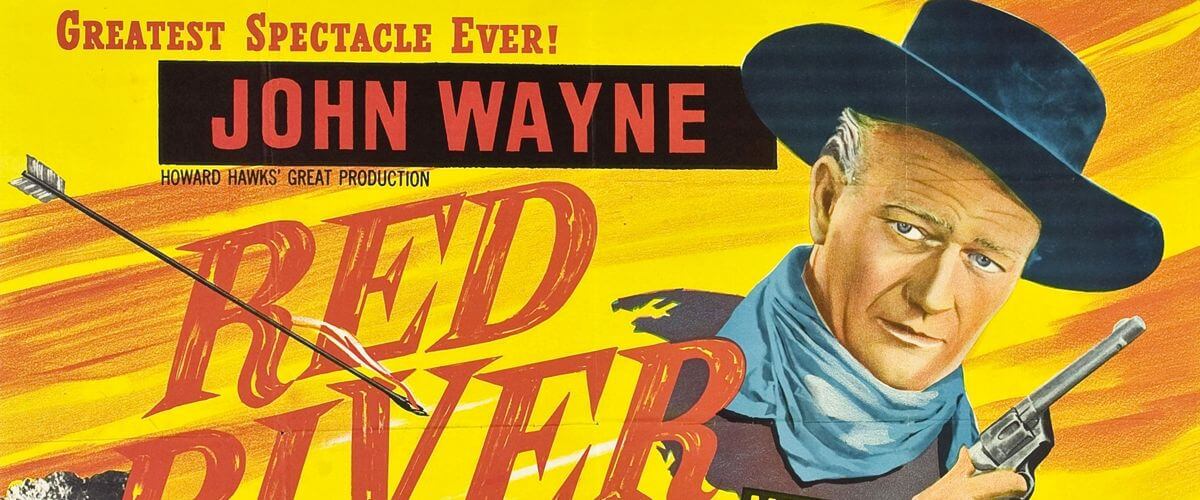

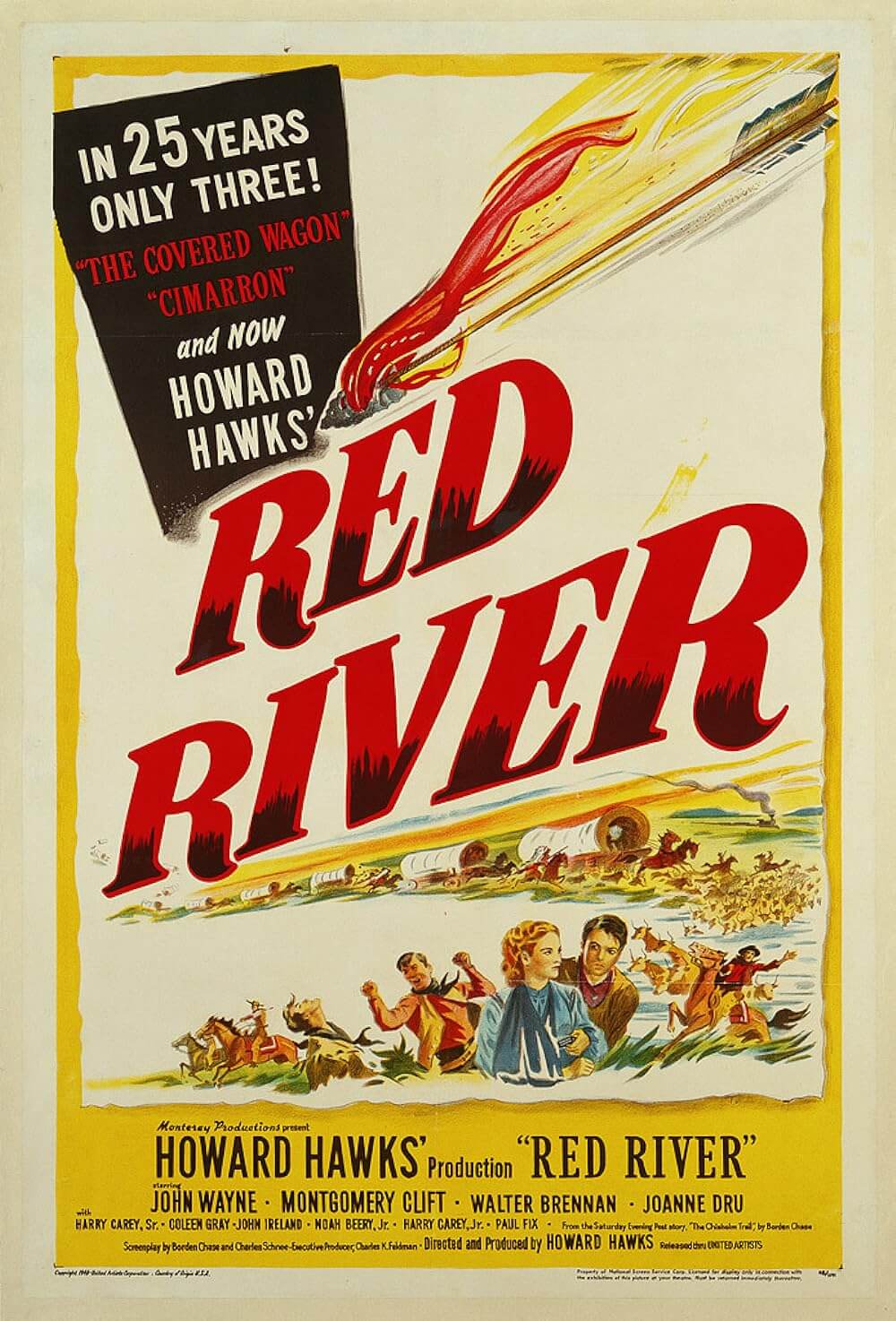

Red River (1948)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

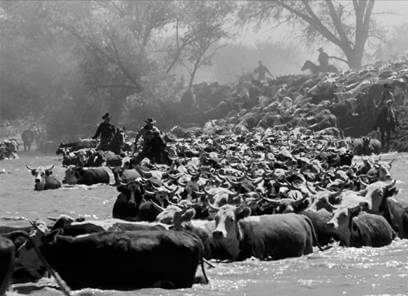

Westerns often take well-known episodes of American history and build them up into iconographic films, but few are more tightly rooted in history and the experience of the West than Howard Hawks’ Red River. A tale of the original cowboys and their first monumental cattle drive along the renowned Chisholm Trail from Texas to Kansas, and by extension how the ensuing industry birthed a nation, the film stands as a grandiose epic about the culture and challenges of the Old West. More than dates and locations in history, Hawks commands Western visual reality, a spatial realism in which he immerses the viewer in the trail hand experience. While cowboy characters discuss their hardships on the drive, the film’s location photography features thousands of head of cattle moving over difficult terrain, all of it rendered with an intractable linear continuity embedded into the mise-en-scène and narrative. Writing for Time, critic James Agee wrote, “There is a constant illusion that you are watching an extraordinary effort to get cattle across a certain immense expanse of difficult and threatening country, that you are learning a lot about how such a job feels and gets done.” But for all the film’s practicality and attention to detail, Red River is also an extraordinary story less concerned about propelling a standard Hollywood spectacle than its own interconnectedness with American identity.

Devoid of melodrama or overtly expressive sentiment, Hawks’ pictures were frequently about self-styled men, such as the rise of Paul Muni’s gangster in Scarface (1932), Cary Grant’s daring air mail pilot in Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Humphrey Bogart’s loner fishing boat captain in To Have and Have Not (1944), or Bogie’s sly detective in The Big Sleep (1946). By the mid-1940s, after two decades and almost thirty films in almost every genre conceivable, Hawks set out to make his first Western—a classic kind of Western where a pioneer carves out a piece of land for himself and builds an empire. It would be a Western complete with sharpshooters who test their skill by putting bullets into a tin can, with Indian attacks of Camanche arrows and raiding parties, with thousands of cattle racing in an exhilarating stampede sequence, and a cattle drive that begins with a montage of rugged cowboy faces waving their hats as they cry yee-haw! to start their journey. Red River would be Hawks’ first Western of five, a surprisingly small number given the forty-plus films to his legendary name, which, along with the names John Ford and Anthony Mann, has long been associated with the Western genre.

John Wayne plays Thomas Dunson, a cattleman who leaves his wagon train convoy with nothing but one bull, two cows, a wagon, and trusty old-timer Groot Nadine (Walter Brennan) by his side. Heading into the lawless Western frontier where there’s no local authority over him, Dunson leaves behind a woman, Fen (Coleen Gray), whom he promises to send for, but she soon dies in an Indian attack. Seeing the smoke from the attack from afar, Dunson resolves that going back now would be pointless. She’s gone. Out of the massacre comes an orphaned boy, Matthew Garth (Mickey Kuhn), whom Dunson agrees to take in. Since Matt is accompanied by a cow and with it can offer Dunson the makings of a herd and cattle farm, Matt wants a partnership and his initial on Dunson’s newly formed “Red River D” brand. Dunson says the boy has to earn it. The three of them continue onward and settle on a plot of land that stretches as far the eye can see. Mexican riders arrive and dispute Dunson’s claim to the land, and Dunson unceremoniously kills one of them to begin his empire. Fourteen years pass. By 1865, time has made its mark on Dunson and Groot. They’ve aged from brown hair and shaven faces to grayed manes and scruffy chins; Dunson has a scar on his cheek, while Groot’s mouth is emptied of teeth. Matt (now played by Montgomery Clift) has grown into a young man who, back from the Civil War, returns to a southern economy ruined by carpetbaggers. Now almost bankrupt, Dunson is desperate to drive his livestock to Missouri where buyers will pay several dollars a head, but the trail is dangerous, riddled with border gangs, Indian attacks, and river crossings. Matt and Groot join the drive at Dunson’s side, as does young sharpshooter Cherry Valance (John Ireland) and dozens of cowboys contracted to Dunson’s ranch.

John Wayne plays Thomas Dunson, a cattleman who leaves his wagon train convoy with nothing but one bull, two cows, a wagon, and trusty old-timer Groot Nadine (Walter Brennan) by his side. Heading into the lawless Western frontier where there’s no local authority over him, Dunson leaves behind a woman, Fen (Coleen Gray), whom he promises to send for, but she soon dies in an Indian attack. Seeing the smoke from the attack from afar, Dunson resolves that going back now would be pointless. She’s gone. Out of the massacre comes an orphaned boy, Matthew Garth (Mickey Kuhn), whom Dunson agrees to take in. Since Matt is accompanied by a cow and with it can offer Dunson the makings of a herd and cattle farm, Matt wants a partnership and his initial on Dunson’s newly formed “Red River D” brand. Dunson says the boy has to earn it. The three of them continue onward and settle on a plot of land that stretches as far the eye can see. Mexican riders arrive and dispute Dunson’s claim to the land, and Dunson unceremoniously kills one of them to begin his empire. Fourteen years pass. By 1865, time has made its mark on Dunson and Groot. They’ve aged from brown hair and shaven faces to grayed manes and scruffy chins; Dunson has a scar on his cheek, while Groot’s mouth is emptied of teeth. Matt (now played by Montgomery Clift) has grown into a young man who, back from the Civil War, returns to a southern economy ruined by carpetbaggers. Now almost bankrupt, Dunson is desperate to drive his livestock to Missouri where buyers will pay several dollars a head, but the trail is dangerous, riddled with border gangs, Indian attacks, and river crossings. Matt and Groot join the drive at Dunson’s side, as does young sharpshooter Cherry Valance (John Ireland) and dozens of cowboys contracted to Dunson’s ranch.

Though there are rumors of a railway line in Abilene, Kansas, and therein a safer route for the journey, Dunson demands they go hundreds of miles northward to Missouri where the landscape is tougher and the territory more violent. Nonetheless, Missouri isn’t a gamble with Dunson’s legacy, some 9,000 head of cattle. The drive proves harder than anyone imagined. The men are tired and cattle are lost every day. One night, a raging stampede kills a man. Later, a half-dead cowboy from further down the trail warns of border gang attacks. Supplies quickly dwindle, and the men must survive on beef alone; no coffee, and no comforts of any kind. But their low morale gains no support from the tyrannical Dunson, who, increasingly unsympathetic, begins to lose himself to drink. The men reach their limit when, after Dunson insists on the difficult crossing of the Red River over an easier path a few hours downriver, three trail hands abandon the drive. Dunson sends Cherry after them. Cherry returns with just two, the other having been shot. Compelled by his own variety of trail justice, Dunson plans to lynch the deserters. But Matt mutinies against his erratic behavior, takes control of the drive, and resolves to take the cattle to Abilene. Betrayed and bitter, Dunson vows to kill Matt out of vengeance and take back his herd. Nevermind that Dunson adopted Matt. For Dunson, killing his adopted son would be no more difficult than killing the Mexican who set foot on his land; or, no more difficult than walking away from Fen, despite her pleas to take her along, and not shedding a single tear at her presumed death.

And so, Matt leads the men toward Abilene. On the way, they rescue a wagon train under attack by an Indian raiding party. Among the survivors is Tess Millay (Joanne Dru), one of “a bunch of… of… [prostitutes]” who holds her own during the encounter. Matt and Tess quickly fall in love, and he gives her the gold bracelet which was given to him by Dunson, who had received it from his mother and gave it to Fen. After killing the Indian who took it from Fen, Dunson gave it to Matt as a symbol of their familial bond. As Matt and the men continue the drive and finally reach Abilene, where a gracious cattle baron (Harry Carey) offers upwards of twenty dollars a head, Dunson and several hired guns advance on the herd. Dunson reaches Tess’ camp and, after talking with her, proposes that she bear him a son in exchange for half his empire. Tess agrees, but only if Dunson will resign his mission of revenge, but Dunson refuses, seeing she’s clearly fallen for Matt and wears his treasured family bracelet. She tries to protect Matt the best she can, explaining that Matt refused to let her come along to Abilene; Matt said he would send for her, just as Dunson had once done with Fen, and so she would do anything to protect him. When Dunson arrives in Abilene, Cherry draws on him; in spite of inflicting a flesh wound on Dunson’s arm, Cherry loses the draw. Dunson continues on to Matt, and the two launch into a brutal and incensed brawl. Tess interjects and pulls a gun on them; she demands they give up their fight and realize they love each other. Shamed into calming down, Dunson and Matt reconcile over the new Red River brand; Dunson draws out the insignia, a D for Dunson on one side of two river lines, and an M for Matt on the other.

And so, Matt leads the men toward Abilene. On the way, they rescue a wagon train under attack by an Indian raiding party. Among the survivors is Tess Millay (Joanne Dru), one of “a bunch of… of… [prostitutes]” who holds her own during the encounter. Matt and Tess quickly fall in love, and he gives her the gold bracelet which was given to him by Dunson, who had received it from his mother and gave it to Fen. After killing the Indian who took it from Fen, Dunson gave it to Matt as a symbol of their familial bond. As Matt and the men continue the drive and finally reach Abilene, where a gracious cattle baron (Harry Carey) offers upwards of twenty dollars a head, Dunson and several hired guns advance on the herd. Dunson reaches Tess’ camp and, after talking with her, proposes that she bear him a son in exchange for half his empire. Tess agrees, but only if Dunson will resign his mission of revenge, but Dunson refuses, seeing she’s clearly fallen for Matt and wears his treasured family bracelet. She tries to protect Matt the best she can, explaining that Matt refused to let her come along to Abilene; Matt said he would send for her, just as Dunson had once done with Fen, and so she would do anything to protect him. When Dunson arrives in Abilene, Cherry draws on him; in spite of inflicting a flesh wound on Dunson’s arm, Cherry loses the draw. Dunson continues on to Matt, and the two launch into a brutal and incensed brawl. Tess interjects and pulls a gun on them; she demands they give up their fight and realize they love each other. Shamed into calming down, Dunson and Matt reconcile over the new Red River brand; Dunson draws out the insignia, a D for Dunson on one side of two river lines, and an M for Matt on the other.

Like several notable directors and producers throughout Hollywood in the mid-1940s, all desperate to escape the machinery of the big studios like Warner Bros. and Paramount and form their own production companies, Hawks left the studio system and developed Monterey Productions with his executive producer Charles Feldman and Hawks’ then-wife Slim Keith. Feldman regularly acquired literary material for Hawks to adapt to film, and several properties came and went through the Monterey Productions offices until 1946, when Hawks read Borden Chase’s serialized story “The Chisholm Trail” in The Saturday Evening Post, which concluded its run in January 1947 and later that year was published in hardback form under the title Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail. Hawks purchased the rights for fifty thousand and paid Chase an additional $1,250 a week to adapt the material into a screen story that every major studio would reject, leaving Monterey to produce it independently. Meanwhile, Hawks found Chase difficult to work with given the author’s dogmatic tendencies and unsubtle writing style. Hawks then hired a young writer named Charles Schnee to develop Chase’s script; Schnee would go on to write Anthony Mann’s The Furies (1950) and Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Schnee’s rewrite, renamed Red River after Chase’s original suggestions “Break Of Dawn” and “The Chisholm Trail” were rejected, added much to the story. Among his greatest contributions was Fen, who Dunson loses after the opening sequence. Fen’s death makes Dunson a tragic, enduring figure, and sets up a pronounced parallel between him and Matt; yet it also removes a woman’s “civilizing influence” on a man, leaving him to create his own, singular rules on the uninhibited Western frontier.

John Wayne wasn’t Hawks’ first choice for Dunson; nor was Montgomery Clift the director’s initial pick for Matt, nor John Ireland for Cherry. Hawks originally wanted Gary Cooper, rodeo rider Casey Tibbs, and Cary Grant respectively. But Cooper rejected the part, finding Dunson unsympathetic; Tibbs, though an appealing choice as a real-life cowboy, would have been too difficult to direct; and Grant felt Cherry was too small a role. Wayne was recommended to Hawks by Feldman, who also represented the actor. He had performed a number of tall and sturdy heroes for John Ford in Stagecoach (1939) and Fort Apache (1948), but not until playing Dunson did Wayne deliver the kind of wounded, complicated roles that Ford later assigned him in The Searchers (1956) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Another Ford alum, Ireland was a relative newcomer and had appeared in My Darling Clementine (1946) as one of the Clantons. But to match Wayne’s sheer size and presence, not to mention his onscreen showmanship, Hawks found method actor Clift, then a 26-year-old Broadway star hesitant about making his Hollywood debut. When Clift eventually agreed to play Matt, he did so knowing it would be a star-making role; after all, just as Matt takes command of the drive, Clift’s character would become the focal point of the narrative. Not only epic for its imposing metaphor in which the cattle drive represents a national push toward Manifest Destiny, Red River harbors a persistent theme from Greek tragedy where the son outperforms the father and replaces him, a theme which tests its actors—and therein would solidify Clift’s star status in a role where his character outperforms the Duke.

John Wayne wasn’t Hawks’ first choice for Dunson; nor was Montgomery Clift the director’s initial pick for Matt, nor John Ireland for Cherry. Hawks originally wanted Gary Cooper, rodeo rider Casey Tibbs, and Cary Grant respectively. But Cooper rejected the part, finding Dunson unsympathetic; Tibbs, though an appealing choice as a real-life cowboy, would have been too difficult to direct; and Grant felt Cherry was too small a role. Wayne was recommended to Hawks by Feldman, who also represented the actor. He had performed a number of tall and sturdy heroes for John Ford in Stagecoach (1939) and Fort Apache (1948), but not until playing Dunson did Wayne deliver the kind of wounded, complicated roles that Ford later assigned him in The Searchers (1956) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Another Ford alum, Ireland was a relative newcomer and had appeared in My Darling Clementine (1946) as one of the Clantons. But to match Wayne’s sheer size and presence, not to mention his onscreen showmanship, Hawks found method actor Clift, then a 26-year-old Broadway star hesitant about making his Hollywood debut. When Clift eventually agreed to play Matt, he did so knowing it would be a star-making role; after all, just as Matt takes command of the drive, Clift’s character would become the focal point of the narrative. Not only epic for its imposing metaphor in which the cattle drive represents a national push toward Manifest Destiny, Red River harbors a persistent theme from Greek tragedy where the son outperforms the father and replaces him, a theme which tests its actors—and therein would solidify Clift’s star status in a role where his character outperforms the Duke.

On a budget of over $1.2 million, Hawks shot much of the picture on location in Elgin, Arizona on Rain Valley Ranch, a section of land that contained the various terrains needed for the picture, including mountains and plains and rivers, all within a mere fifteen miles from one another. While much of the film takes place on the wilderness drive, the Abilene set was constructed with false fronts at Samuel Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood. Hawks hired cinematographer Russell Harlan for their first collaboration of seven, among them the Westerns The Big Sky (1952) and Rio Bravo (1959). Hawks even considered shooting Red River in color but resolved that it would have looked “garish”. Before shooting could begin, the director was required to meet with Joseph Breen of the Production Code to review the script. Breen cited the screenplay’s sexual innuendos, murders made with impunity, women who were impliedly prostitutes, mistreatment of animals, and an overall air of brutality. Hawks was forced to remove things like Groot’s line “It’ll make a better man out of me in less time it takes a rooster to make a chicken grin” and the pronounced sexual interplay between Matt and Tess. But Breen somehow overlooked the homoerotic tension between Matt and Cherry. In the scene where the two sharpshooters compare guns, Cherry handles Matt’s pistol and says, “That’s a good-looking gun… Maybe you’d like to see mine?” Elsewhere, Hawks expanded Walter Brennan’s role to offer a redemptive figure loyal to Dunson, and also to add comic relief. Hawks convinced Brennan to play an old codger without his false teeth, leading to one of the film’s most amusing asides when Groot loses his teeth to his Native American chum Quo (Chief Yowlanchie) in a poker game. At the same time, Hawks’ displeasure with John Ireland’s erratic presence during the shoot (drinking and sleeping on the set, affairs with fellow castmembers Joanne Dru and Shelley Winters, and so on) led to Hawks trimming down the role of Cherry Valance.

Hawks’ shoot suffered delays due to the downpours that pummeled the aptly named Rain Valley Ranch, contended with fifteen hundred cows, and required the director to mediate on-set cliques among his cast. Wayne thought Clift looked “a little queer”, and his usual hard-drinking, poker-playing, macho entourage was a far cry from Clift’s crowd. The young actor had a moody presence and remained ever-serious about forming his craft, whereas Wayne’s talent came naturally. Clift soon learned there was no upstaging the Duke, no matter how the story played out. Wayne was a firmly established Western figure, his towering physicality and hardened off-screen persona unmatched. The rookie film actor, Clift had trained for weeks with real cowboys to acquire the look and skill needed to appear natural on the cattle drive; but contending with Wayne would be another matter. Under Hawks’ guidance, Clift broke out of his stage-born devotion to the script and learned that improvisation with his fellow actors gave way to limitless possibilities in a scene. Clift’s quiet confidence onscreen as Matt, and the film’s build-up of his sharpshooting skills and mysterious war years gradually affirms the character, and suggests his abilities are ready to explode from under the surface. When it happens and Matt finally takes over the drive, Matt and the ungovernable Dunson have been so decisively developed that the ensuing conflict and anticipation of their meeting again is filled with dread, like the collision of two great storms. Through the skill of the performances, in one instant Matt becomes our hero and Dunson transforms into a fearsome, single-minded juggernaut stalking the drive.

Hawks’ shoot suffered delays due to the downpours that pummeled the aptly named Rain Valley Ranch, contended with fifteen hundred cows, and required the director to mediate on-set cliques among his cast. Wayne thought Clift looked “a little queer”, and his usual hard-drinking, poker-playing, macho entourage was a far cry from Clift’s crowd. The young actor had a moody presence and remained ever-serious about forming his craft, whereas Wayne’s talent came naturally. Clift soon learned there was no upstaging the Duke, no matter how the story played out. Wayne was a firmly established Western figure, his towering physicality and hardened off-screen persona unmatched. The rookie film actor, Clift had trained for weeks with real cowboys to acquire the look and skill needed to appear natural on the cattle drive; but contending with Wayne would be another matter. Under Hawks’ guidance, Clift broke out of his stage-born devotion to the script and learned that improvisation with his fellow actors gave way to limitless possibilities in a scene. Clift’s quiet confidence onscreen as Matt, and the film’s build-up of his sharpshooting skills and mysterious war years gradually affirms the character, and suggests his abilities are ready to explode from under the surface. When it happens and Matt finally takes over the drive, Matt and the ungovernable Dunson have been so decisively developed that the ensuing conflict and anticipation of their meeting again is filled with dread, like the collision of two great storms. Through the skill of the performances, in one instant Matt becomes our hero and Dunson transforms into a fearsome, single-minded juggernaut stalking the drive.

With Hawks’ generally slow pace to filmmaking, his incurable failure to finish a picture on schedule, the endless weather delays, and the rewrites around unreliable actors, the budget skyrocketed to $2.8 million, a huge sum in those days. No doubt the major studios that had turned Hawks’ proposed project down thanked their lucky stars. The final scene shot was the stampede, a sequence and its accompanying scenes filmed by second unit director Arthur Rosson. The sequence was shot over thirteen days and used thirty-five cattle wranglers; according to Todd McCarthy’s book Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood, “Seven men were hurt, thirteen horses and mules were crippled, one steer died, and sixty-nine steers were injured or crippled in the course of filming.” Editing the epic picture took months and was an imposing challenge to maintain the film’s character-driven drama amid the film’s many majestic sequences set across the Western countryside. Through several varied cuts and debates about its length with the distributing company at United Artists (created by Charles Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks in 1919, UA was the home for filmmakers desperate to escape the studio system), Hawks knew he had achieved what he set out to do, and jealously stalled delivering the final cut. In the end, two versions of Red River were completed by editor Christian Nyby, while Hawks busied himself elsewhere: Howard Hughes threatened legal action over the film’s ending, which was substantially similar to the one in The Outlaw (1943), an ending Hawks helped Hughes write; UA’s pressures to hand over the final print for distribution; and while Red River was in post-production, Hawks oversaw direction of A Song is Born, which was also due in 1948.

In the editing room, many of the most important creative decisions were left to Nyby, and neither of the two versions produced received Hawks’ unqualified stamp of approval. The differences between the two versions are subtle but crucial. The Pre-Release Cut features a diary-like structure whereby the story’s episodic events are chronicled in a journal called “Early Tales of Texas” and paged through as the film progresses. The Theatrical Cut contains the “Early Tales of Texas” book opening, but the film is structured around narration by Walter Brennan’s character. Each version has its merits, depending on the viewer’s preference for the chosen structural device, although the Pre-Release Cut contains an additional seven minutes of footage, including several shots and dialogue that expand and clarify the dynamic between Dunson and Matt in their showdown. Nevertheless, Hawks later told Peter Bogdanovich that he favored the voice-over: “[The narration] brought it closer to you because we had a very distinctive voice doing it.” Indeed, Brennan’s voiceover as Groot develops the drama and personal perspective amid the more grandiose history-in-the-making elements of the storytelling. Meanwhile, as Nyby completed the two cuts, Hawks sailed for Germany in August 1948 to shoot I Was a Male War Bride; the next month, Red River was released to positive reviews and outstanding business, earning $4.1 million in domestic receipts. Montgomery Clift became an instant star whose photos adorned the walls of many a teenage girl, while John Wayne’s complex performance earned accolades. Famously, after seeing Red River, John Ford remarked to Hawks, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act,” and then began to give Wayne more demanding roles. But after all the legal troubles and delays, the production didn’t earn a profit until Red River was reissued into theaters in 1952.

In the editing room, many of the most important creative decisions were left to Nyby, and neither of the two versions produced received Hawks’ unqualified stamp of approval. The differences between the two versions are subtle but crucial. The Pre-Release Cut features a diary-like structure whereby the story’s episodic events are chronicled in a journal called “Early Tales of Texas” and paged through as the film progresses. The Theatrical Cut contains the “Early Tales of Texas” book opening, but the film is structured around narration by Walter Brennan’s character. Each version has its merits, depending on the viewer’s preference for the chosen structural device, although the Pre-Release Cut contains an additional seven minutes of footage, including several shots and dialogue that expand and clarify the dynamic between Dunson and Matt in their showdown. Nevertheless, Hawks later told Peter Bogdanovich that he favored the voice-over: “[The narration] brought it closer to you because we had a very distinctive voice doing it.” Indeed, Brennan’s voiceover as Groot develops the drama and personal perspective amid the more grandiose history-in-the-making elements of the storytelling. Meanwhile, as Nyby completed the two cuts, Hawks sailed for Germany in August 1948 to shoot I Was a Male War Bride; the next month, Red River was released to positive reviews and outstanding business, earning $4.1 million in domestic receipts. Montgomery Clift became an instant star whose photos adorned the walls of many a teenage girl, while John Wayne’s complex performance earned accolades. Famously, after seeing Red River, John Ford remarked to Hawks, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act,” and then began to give Wayne more demanding roles. But after all the legal troubles and delays, the production didn’t earn a profit until Red River was reissued into theaters in 1952.

In the years since its release, nearly every critic and film scholar, no matter how devoted to Hawks, has acknowledged that the ending of Red River is a letdown, signaled by the stark tonal shift incited by Tess and the unrealized death of either Dunson or Matt. In Chase’s original text, Dunson is mortally wounded during the shootout, then Matt and Tess return him to Texas, where he dies. But there is no explosion of mortal violence at the end of Red River, perhaps because Hawks never set out to make a tragedy; rather, he made a picture that is both a historical marker and a portrait of American identity. This ending can be unsatisfying for filmgoers accustomed to death as a standard resolution in Westerns. However, it is through the reconciliation in the finale that Red River‘s most significant themes are underscored. The theme of a family passing on a tradition is solidified only after Dunson and Matt make peace, but it’s established even earlier when Tess and Dunson first meet and she outlines the parallels between herself and Dunson’s lost love, Fen. At this moment, the viewer must know that Dunson could never allow history to repeat itself—he could never rob Tess of Matt the way he was robbed of Fen. Tess realizes this later as well; after the two reconcile she exclaims “What a fool I’ve been!” to think Dunson and Matt would ever kill one another. On the reverse, Matt has no need to kill Dunson; he has already won for both of them by delivering the herd after he set the drive on his own course to Kansas. When Dunson recognizes this and forms a new brand for their company, he and Matt cease being business partners and finally begin to act like a father and son. And through the visual device and passing-on of Dunson’s gold bracelet, Tess becomes Matt’s version of Fen. The torch has been passed, and in turn Dunson has realized the greatest hopes for his frontier life vicariously through Matt.

What could be more American that these characters who embrace their history and forge ahead in the end? And all because of Hawks’ brand of conflict-resolution was that of a pragmatist-artist, not a director of Hollywood melodramas. But the film’s swelling of conflicts between Dunson and Matt, or between Matt and Cherry, seems to anticipate violence, and yet both conflicts are resolved without the need for overly dramatic death. In the film, Tess, who leaps into the scene and breaks up the final fight, has been described as a “deus ex machina” required by the plot; or rather, required by Hawks, who, according to McCarthy, “increasingly refrained from killing off remotely sympathetic characters” in his films. But Tess represents a familiar trope in Hawksian storytelling, where a sole woman brings rational thinking to a world of self-styled, self-destructive men. Consider how Jean Arthur is the only sane person in a company of daredevil pilots in Only Angels Have Wings, or how Angie Dickinson in Rio Bravo presents a stable-minded, liberal alternative to the stubborn, violent goings-on in the sheriff’s office. Much like the schoolmarm in Ford’s My Darling Clementine, women represent modern society in Westerns, the forming of law and culpability in the Wild West through the civilizing process. Women in Hawks’ films often represent the rational, whereas men are swept up in the film’s treacherous proceedings—which are violent and exciting, but rarely rational. Women are the voices of reason in Hawks’ pictures, and Tess in Red River is no exception. She brings an air of good reason to an otherwise male-dominated and unreasonable force of vengeance and self-destruction driving the narrative, while also being the thematic connective tissue that links Dunson’s distant past to Matt’s future.

What could be more American that these characters who embrace their history and forge ahead in the end? And all because of Hawks’ brand of conflict-resolution was that of a pragmatist-artist, not a director of Hollywood melodramas. But the film’s swelling of conflicts between Dunson and Matt, or between Matt and Cherry, seems to anticipate violence, and yet both conflicts are resolved without the need for overly dramatic death. In the film, Tess, who leaps into the scene and breaks up the final fight, has been described as a “deus ex machina” required by the plot; or rather, required by Hawks, who, according to McCarthy, “increasingly refrained from killing off remotely sympathetic characters” in his films. But Tess represents a familiar trope in Hawksian storytelling, where a sole woman brings rational thinking to a world of self-styled, self-destructive men. Consider how Jean Arthur is the only sane person in a company of daredevil pilots in Only Angels Have Wings, or how Angie Dickinson in Rio Bravo presents a stable-minded, liberal alternative to the stubborn, violent goings-on in the sheriff’s office. Much like the schoolmarm in Ford’s My Darling Clementine, women represent modern society in Westerns, the forming of law and culpability in the Wild West through the civilizing process. Women in Hawks’ films often represent the rational, whereas men are swept up in the film’s treacherous proceedings—which are violent and exciting, but rarely rational. Women are the voices of reason in Hawks’ pictures, and Tess in Red River is no exception. She brings an air of good reason to an otherwise male-dominated and unreasonable force of vengeance and self-destruction driving the narrative, while also being the thematic connective tissue that links Dunson’s distant past to Matt’s future.

For Red River, Hawks sought to embrace the fundamental history of the West over any factual history; for example, the film claims the Chisholm Trail was founded in 1865, though it was, in reality, two years later. Such specificities are not important. The history that is the film’s subject is fixed in the stories told over campfires among trail hands, in the cattle moving across the land by the thousands, and the legends that are made all along the Chisholm Trail. However great the wholly unjustified resistance to the film’s conclusion on a cinematic level may be, the overall narrative epitomizes the pointedly American institution of legends and families and traditions passed down amongst generations. A classical story about the beginning of the West, a story about pioneers venturing into the unknown to form a legacy, a story about Americans, what happens to the characters in Red River is less important than the journey and what was ultimately accomplished. In these “Early Tales of Texas”, Hawks creates a motion picture that evokes the intangible, proud American Spirit as it once existed on the Western frontier. As a filmmaker and storyteller, Hawks channeled existing motifs—both Hawksian self-styled men and rational women—in his present body of work and applied them, quite sensibly, to the Western genre. And perhaps the way Hawks’ recurrent and long-established narrative themes fit so naturally into the genre is why, after making so few Westerns, his name is synonymous with Western masterpieces.

Bibliography:

Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Devil Made It. New York: Alfred A.Knopf, 1997.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Liandrat-Guigues, Suzanne. Red River (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, 2000.

McCarthy, Todd. Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review