The Definitives

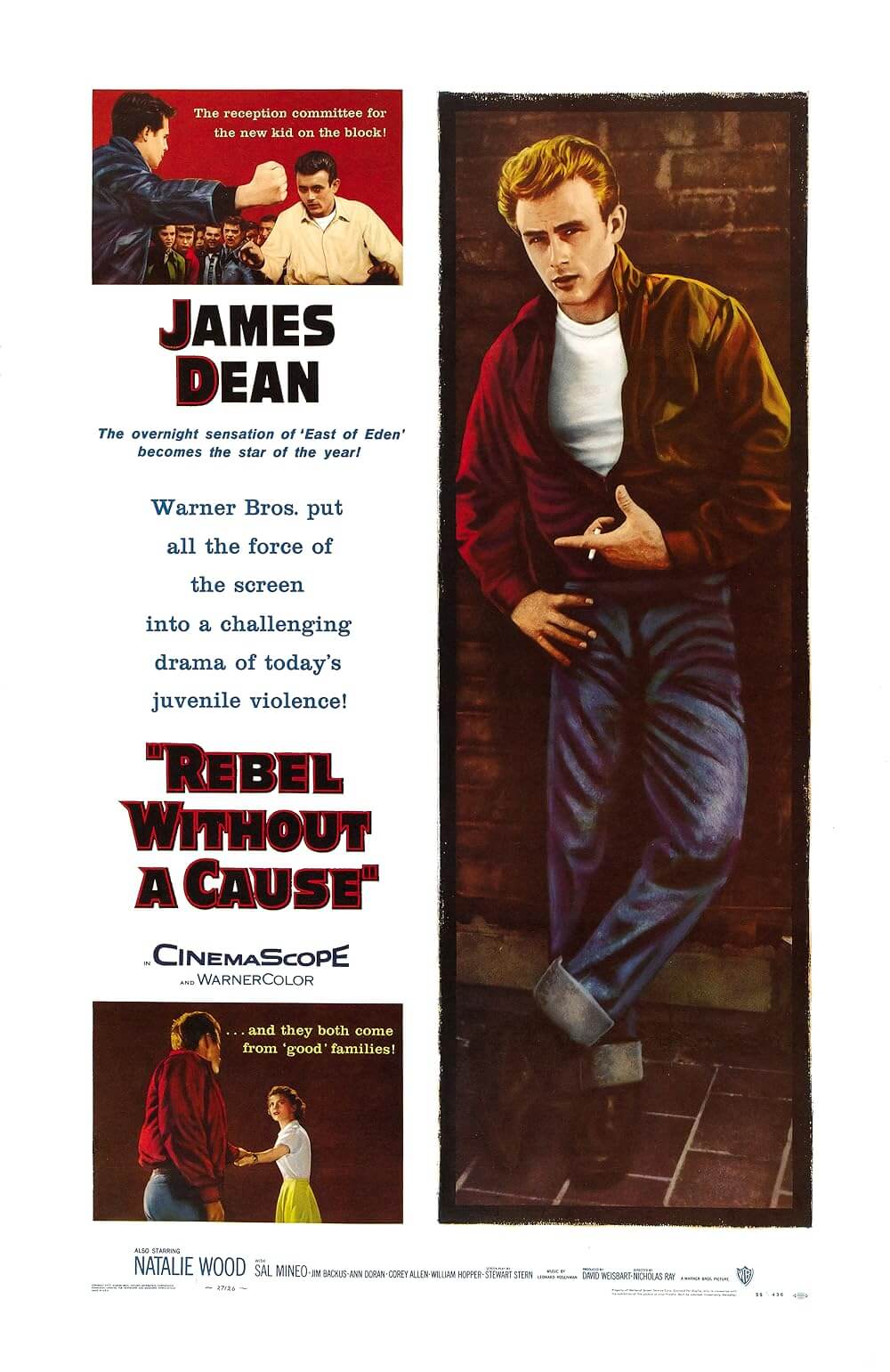

Rebel Without a Cause

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Director Nicholas Ray captured the feelings of an entire generation of teenagers in Rebel Without a Cause, a picture that ushered in a movement of teen films and, following the phenomenon of its release, solidified an entirely new market in Hollywood, one exclusive to the otherwise unrepresented teenager. Through the film, a division of young adults received a personality and individualism never before represented onscreen, establishing their place within their own unique cultural identity, language, and social rituals, as represented by Ray’s picture and in those which followed to use his film as a benchmark. Ray’s picture was the first to “get” 1950s adolescents with all their conflicts, oblivious parents, sexual confusion, social anxiety, and alienation. Fuelling its historical significance further, the film implanted star James Dean as an enduring icon for his posthumous screen appearance as the central hero, a knife wielding, car racing, juvenile discontent or “delinquent”. But the beauty and complexity of Ray’s landmark 1955 film often go overlooked in favor of its influence on American pop-culture. In a powerful melodrama about family, friendship, and identity, Ray’s film adopts an extraordinarily mannered stylization in terms of both his visual approach and the expressiveness of the performances, an almost dreamlike personality that evokes the heightened, unfocused wave of emotions and surreal perceptions felt in adolescence.

More intimate even than its style or the potency of the drama, Rebel Without a Cause seems to crystallize lifelong feelings of estrangement felt by its auteur director. Nicholas Ray was out of place in Hollywood where his films like In a Lonely Place (1950) and Johnny Guitar (1954) were often undervalued upon their initial release in America, only to be reassessed and lauded after his death. At first, it was only French cinéastes, who would later become New Wave filmmakers, who saw Ray’s unique blend of reality and melodrama as the certain signs of an auteur. Writing in the Cahiers du cinéma, Éric Rohmer wrote “We deem Nicholas Ray to be one of the greatest—[Jacques] Rivette would say the greatest, and I would willingly endorse that—of the new generation [postwar] American filmmakers… In spite of his obvious lack of pretentions, his is one of the few to possess his own style, his own vision of the world, his own poetry; he is an auteur, a great auteur.” In his personal life, Ray was a kind of eternal teen, feeling his way through one day to the next, looking for a makeshift family in which he could feel at home. He found such “families” in artistic and political communities such as communism and various acting or artistic troupes, but he was also an iconoclast, a notorious womanizer, and lifelong bisexual—in other words, he felt that he was an outsider, unable to make stable connections or fit in . In his youth, his parents failed to provide a steady environment, and his own failures as a father remained a permanent regret throughout his life. Better than anyone, he could identify with the teens in Rebel Without a Cause, their need and ultimate failure to find a stable family.

Rebel Without a Cause follows restless teen Jim Stark (James Dean) as he searches for meaning in his middle-class existence under the indignity of his clueless parents, an emasculated father (Jim Backus), whose household is run by the family’s domineering mother (Ann Doran) and her mother Grandma Stark (Virginia Brissac). After taking out his anger by slugging a juvenile officer’s wooden desk in an early scene, Jim tells the cop, “If he had guts to knock Mom cold once, then maybe she’d be happy, and she’d stop picking on him.” A new student at Dawson High School, Jim finds he’s not the only teen with an unsatisfying home life, and he forms his own family of sorts with two fellow students he meets at Juvenile Hall. Playing their family’s mother is Jim’s neighbor Judy (Natalie Wood), a girl who’s picked up by the police one night when she was “Looking for company.” Her daddy issues become apparent when she kisses her father on the cheek and he reacts, “What’s the matter with you? You’re getting too old for that kind of stuff, kiddo. I thought you’d stopped doing that long ago.” “I didn’t want to stop,” she replies. Her father explodes, “Girls your age don’t do things like that!” Judy answers, “Girls don’t love their father? Since when? Since I got to be 16?” Judy’s father is a failure just like Jim’s, but in a different way; he fears his sexual feelings toward Judy. With Jim and Judy playing the parents, they adopt a wayward child in boyish psychopath Plato (Sal Mineo), whose altogether absent parents have been replaced by a concerned African-American housekeeper. Plato, when he’s not killing puppies or creating elaborate, fantastic lies, looks up to Judy as a mother and Jim as a father, if not a hopeful inamorato.

Rebel Without a Cause follows restless teen Jim Stark (James Dean) as he searches for meaning in his middle-class existence under the indignity of his clueless parents, an emasculated father (Jim Backus), whose household is run by the family’s domineering mother (Ann Doran) and her mother Grandma Stark (Virginia Brissac). After taking out his anger by slugging a juvenile officer’s wooden desk in an early scene, Jim tells the cop, “If he had guts to knock Mom cold once, then maybe she’d be happy, and she’d stop picking on him.” A new student at Dawson High School, Jim finds he’s not the only teen with an unsatisfying home life, and he forms his own family of sorts with two fellow students he meets at Juvenile Hall. Playing their family’s mother is Jim’s neighbor Judy (Natalie Wood), a girl who’s picked up by the police one night when she was “Looking for company.” Her daddy issues become apparent when she kisses her father on the cheek and he reacts, “What’s the matter with you? You’re getting too old for that kind of stuff, kiddo. I thought you’d stopped doing that long ago.” “I didn’t want to stop,” she replies. Her father explodes, “Girls your age don’t do things like that!” Judy answers, “Girls don’t love their father? Since when? Since I got to be 16?” Judy’s father is a failure just like Jim’s, but in a different way; he fears his sexual feelings toward Judy. With Jim and Judy playing the parents, they adopt a wayward child in boyish psychopath Plato (Sal Mineo), whose altogether absent parents have been replaced by a concerned African-American housekeeper. Plato, when he’s not killing puppies or creating elaborate, fantastic lies, looks up to Judy as a mother and Jim as a father, if not a hopeful inamorato.

Inside each member of their teen “family” trifecta are unfocused feelings and frustrations about their sense of purposelessness and the choice between living life or not, which their parents have seemingly abandoned. At a field trip to the Griffin Park Observatory, the speaker outlines his theories on the end of the universe, “Through the infinite reaches of space, the problems of man seem trivial and naive indeed, and man existing alone seems himself an episode of little consequence.” To this, Jim can only act out meaninglessly against a new enemy Buzz (Corey Allen) when he’s provoked into a switchblade knife fight and, later that night, in a “chickie run” where two race against each other in hot rods toward a cliff. But there’s a futility to their antagonism and they know it. Before the race, Buzz tells Jim, “You know something? I like you.” Curious, Jim asks, “Why do we do this?” Buzz responds fatalistically, “You got to do something.” When Buzz goes racing off the cliff his friends seek revenge on Jim, in fear that he’ll talk to the police. The trifecta escapes into a familial fantasy by playing “house” at an abandoned mansion, but their brief storybook bliss is interrupted when Buzz’s remaining gang finds them, and Plato reacts in an outburst of frenzied anger and gunfire, shooting one of the boys and at Jim with the gun he’s stolen from his mother. A chase leads them to the nearby Observatory, where Plato is gunned down in an act of suicide by police. Believing Jim was killed, his father rushes to the scene relieved to find his son has survived. He promises to be a better father, the ending bittersweet and tragic, as Jim too, now having lost his temporary son, understands his father and what it feels like to be helpless to protect your child.

Nicholas Ray was born Raymond Nicholas Kienzle in 1911 in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, to a tradesman in his second marriage and a farmer’s daughter. Ray’s mother gave his three sisters plenty of attention, but by the time he reached high school, his siblings had all moved out into marriages and careers and his mother resolved to leave him to his father. Despite growing up during Prohibition, he was raised “under the lash of alcoholism,” complete with physical beatings and resultant juvenile delinquency. His early encounters with the police occurred as a result of heavy teen drinking and car theft. Sexually, when he wasn’t winking at his father’s mistresses, he found himself curious about men; although later in life he became a famous womanizer (conquests include Gloria Grahame, Marilyn Monroe, Shelly Winters, and Joan Crawford), perhaps emulating his father’s drinking and womanizing. Young Ray even learned to drive at 13 to bring his father home from speakeasies. When he was 16, his father, a dope addict, died suddenly and Ray was sent to live with his sister, who introduced him to a night-life of concerts, nightclubs, and theater. By this time, his sister had piqued his interest in the arts, and his need for individuality led Ray Kienzle to become Nicholas Ray with a simple flip-flop of his first and middle name. Meanwhile, Ray began to explore a local stock company, amateur radio, and wrote pieces in his local newspaper where he expressed many a left-wing sentiment.

Nicholas Ray was born Raymond Nicholas Kienzle in 1911 in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, to a tradesman in his second marriage and a farmer’s daughter. Ray’s mother gave his three sisters plenty of attention, but by the time he reached high school, his siblings had all moved out into marriages and careers and his mother resolved to leave him to his father. Despite growing up during Prohibition, he was raised “under the lash of alcoholism,” complete with physical beatings and resultant juvenile delinquency. His early encounters with the police occurred as a result of heavy teen drinking and car theft. Sexually, when he wasn’t winking at his father’s mistresses, he found himself curious about men; although later in life he became a famous womanizer (conquests include Gloria Grahame, Marilyn Monroe, Shelly Winters, and Joan Crawford), perhaps emulating his father’s drinking and womanizing. Young Ray even learned to drive at 13 to bring his father home from speakeasies. When he was 16, his father, a dope addict, died suddenly and Ray was sent to live with his sister, who introduced him to a night-life of concerts, nightclubs, and theater. By this time, his sister had piqued his interest in the arts, and his need for individuality led Ray Kienzle to become Nicholas Ray with a simple flip-flop of his first and middle name. Meanwhile, Ray began to explore a local stock company, amateur radio, and wrote pieces in his local newspaper where he expressed many a left-wing sentiment.

Ray’s education in the arts continued at the University of Chicago under the tutelage of his idol, three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Thornton Wilder, whose plays Ray would star in and later direct, and with whom Ray would form a youth chapter of the U.S. Communist Party. But Ray could be defined by his status as a drifter and soul-searcher; he never spent too long with one institution yet felt desperate to belong. He expressed grand artistic drives but lacked the income to support them, and during this period in his life he would most resemble Dean’s lonely Jim Stark from Rebel Without a Cause. Ray soon married his first wife Jean Evans and joined the bohemian group of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, an experimental society of communal living located in the Wisconsin River valley, where Ray, soon promoted to playhouse director and master of artistic ceremonies, learned his proclivity for such collective living conditions, and where he could embrace his artistic and architectural pursuits. Also, it was at Taliesin where Ray was first exposed to cinema in a meaningful way, their moviehouse showing a regular lineup of foreign films and highbrow Hollywood titles. A common thread in Ray’s life, the future film director soon left abruptly after a falling out with Wright, and their master-apprentice relationship came to an end, the cause believed to be over Ray’s reckless drinking and homosexual drives.

Now based in New York City, Ray joined the Theater of Action, a radical performance troupe and house of Communism in which Elia Kazan, following the teachings of theater director Yevgeny Vakhtangov, taught Ray to turn his “trauma into drama”. Over the next few years, Ray also dabbled in the New York folk music scene, divorced his first wife just three years after having a child together, narrowly avoided the World War II draft under guarded circumstances (reports of a “bad heart,” “rheumatoid arthritis,” and his admission of “homosexual experiences as a young man”), and produced a propagandistic radio show in Washington D.C. called “Voice of America” alongside friend John Houseman. All the while, Ray’s wandering ways, compounded by his frequent left-wing ideals and occasional Communist ties, incited the FBI to open a file on him as early as 1938. Regardless of his behavior and political ties, friends saw him as a “blend of sweetness and vulnerability wrapped in a charismatic macho façade”—a description that echoes both Jim Stark and James Dean. Ray kept searching; he searched endlessly for artistic fulfillment and a place where he might feel at home, and yet he may never have found it. After directing his sole Broadway production, Duke Ellington’s well-received musical Beggar’s Holiday in 1946, friends Kazan and Houseman encouraged Ray to get into film. That same year, Ray started at RKO with aspirations to become another wunderkind like Orson Welles.

Now based in New York City, Ray joined the Theater of Action, a radical performance troupe and house of Communism in which Elia Kazan, following the teachings of theater director Yevgeny Vakhtangov, taught Ray to turn his “trauma into drama”. Over the next few years, Ray also dabbled in the New York folk music scene, divorced his first wife just three years after having a child together, narrowly avoided the World War II draft under guarded circumstances (reports of a “bad heart,” “rheumatoid arthritis,” and his admission of “homosexual experiences as a young man”), and produced a propagandistic radio show in Washington D.C. called “Voice of America” alongside friend John Houseman. All the while, Ray’s wandering ways, compounded by his frequent left-wing ideals and occasional Communist ties, incited the FBI to open a file on him as early as 1938. Regardless of his behavior and political ties, friends saw him as a “blend of sweetness and vulnerability wrapped in a charismatic macho façade”—a description that echoes both Jim Stark and James Dean. Ray kept searching; he searched endlessly for artistic fulfillment and a place where he might feel at home, and yet he may never have found it. After directing his sole Broadway production, Duke Ellington’s well-received musical Beggar’s Holiday in 1946, friends Kazan and Houseman encouraged Ray to get into film. That same year, Ray started at RKO with aspirations to become another wunderkind like Orson Welles.

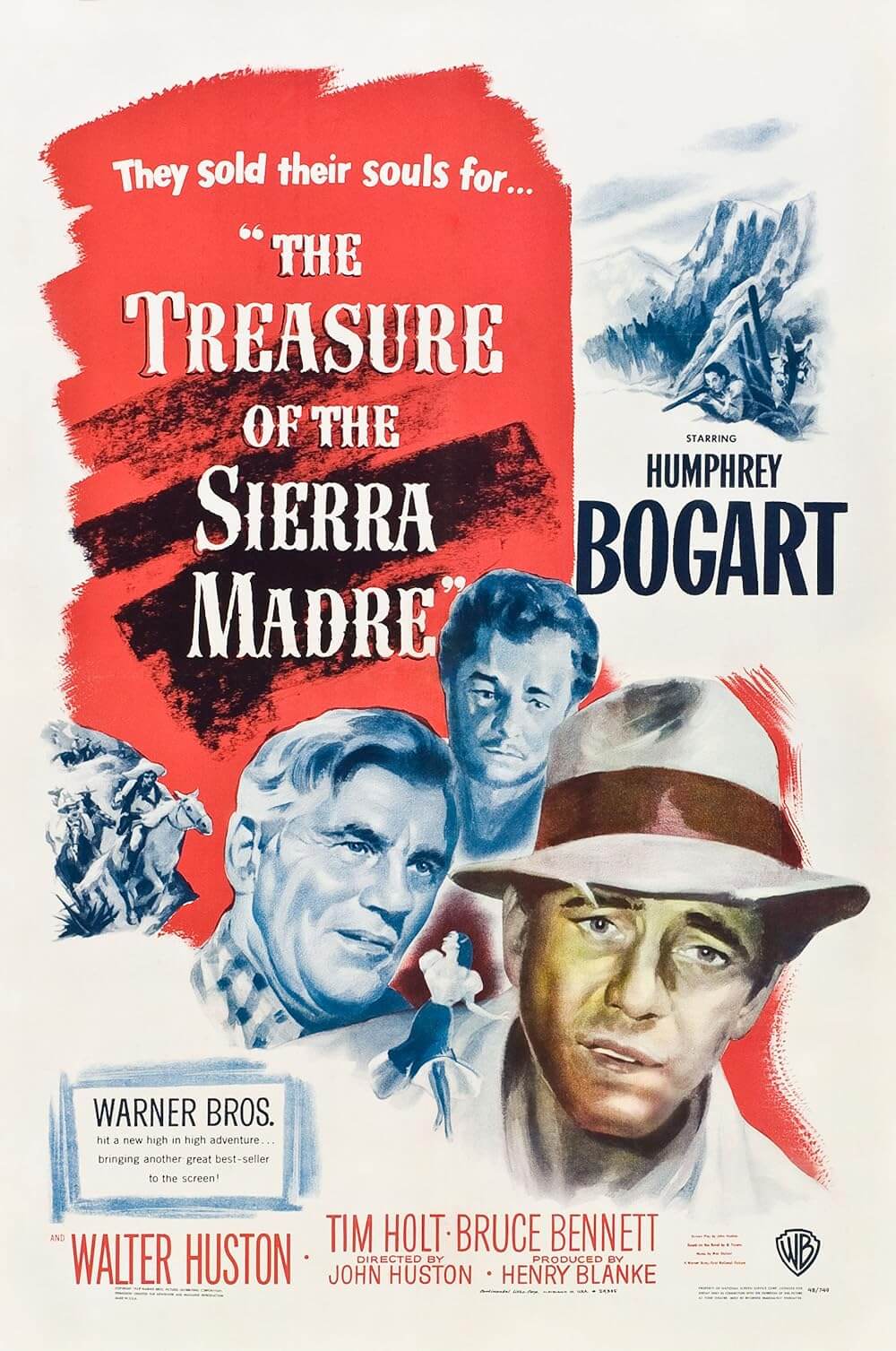

Ray’s first film as director was based on Edward Anderson’s Depression-era novel Thieves Like Us, later retitled They Live By Night, a story of criminal lovers (Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell) on the run from the law. All of Ray’s roaming over the years would finally come together as a director. His stage experience made him adept with actors and developing drama; his time in radio left him with an attuned precision for filmmaking audio equipment; his architectural insights made him aware of lines and how to use the camera frame, employing slanted angles and digging holes for otherwise impossible low angles; he even pioneered the idea of a helicopter for aerial views, now a standard in film production. Though They Live By Night would go unreleased for two years due to RKO’s disorderly takeover by Howard Hughes, in the interim the film was seen in private screening rooms throughout Hollywood by the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Humphrey Bogart, and Ray’s talent behind the camera was apparent. He moved on to make the first picture of Bogart’s independent production company, Santana Pictures Corporation, called Knock on Any Door (1949), followed by several pictures for RKO, including the dark drama A Woman’s Secret (1949), the John Wayne war picture Flying Leathernecks (1951), and the dynamic noir On Dangerous Ground (1951).

Though he was later aggrandized by French critics who saw him as “a symbol of artistic purity and tragic flaws: a test case for auteuristic worship,” Ray never quite found his place in Hollywood. He was a studio filmmaker; however, he was also a nonconformist and wanted to turn the usual types of stories upside-down. In his early years as a director before Rebel Without a Cause, he made solid Hollywood pictures inhabited by moments of greatness and innovation. In a few exceptions, Ray broke new ground with something daring and original. Take the masterful Hollywood-set noir In a Lonely Place, another production under Bogart’s company, where Bogart plays a screenwriter suspected of murder even after his lover (Gloria Grahame), an actress, provides him with an alibi. The film demystifies Bogart’s status as an iconic movie hero and leaves us with rampant suspicion for his sometimes frightening character, who admits he loves the feeling of his hands on a throat, crushing it. A few years later, Ray made his first color picture with the wonderfully operatic Johnny Guitar, a flashy, outrageous Western masterpiece in which gender roles are reversed and women take center stage. Deemed campy and confused by American critics, Johnny Guitar was lauded by the French, especially François Truffaut and other writers of the French magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Regardless, Ray thought Johnny Guitar was a disaster.

Though he was later aggrandized by French critics who saw him as “a symbol of artistic purity and tragic flaws: a test case for auteuristic worship,” Ray never quite found his place in Hollywood. He was a studio filmmaker; however, he was also a nonconformist and wanted to turn the usual types of stories upside-down. In his early years as a director before Rebel Without a Cause, he made solid Hollywood pictures inhabited by moments of greatness and innovation. In a few exceptions, Ray broke new ground with something daring and original. Take the masterful Hollywood-set noir In a Lonely Place, another production under Bogart’s company, where Bogart plays a screenwriter suspected of murder even after his lover (Gloria Grahame), an actress, provides him with an alibi. The film demystifies Bogart’s status as an iconic movie hero and leaves us with rampant suspicion for his sometimes frightening character, who admits he loves the feeling of his hands on a throat, crushing it. A few years later, Ray made his first color picture with the wonderfully operatic Johnny Guitar, a flashy, outrageous Western masterpiece in which gender roles are reversed and women take center stage. Deemed campy and confused by American critics, Johnny Guitar was lauded by the French, especially François Truffaut and other writers of the French magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Regardless, Ray thought Johnny Guitar was a disaster.

In the summer of 1954, as Johnny Guitar was making money in theaters despite being critically panned stateside, and his latest production Run for Cover, a classical Western starring James Cagney, had just been completed, director Nicholas Ray told his agent and Music Corporation of America (MCA) head Lew Wasserman,“I’m tired of doing films for the bread and taxes. I want to make a film that I love… I have to believe in the next one or feel that it’s important… I want to do a film about kids growing up, the young people next door, middle-class kids, their problems.” Virtually nonexistent prior to 1955, films about teenagers were few and far between. Teenagers had appeared in films, of course; but rarely were there films about teendom. Appearances by the Dead End Kids and titles like the Merian C. Cooper-produced drama Finishing School appeared occasionally throughout the 1930s and 1940s, yet few such exceptions represented teens as fully formed characters. Marlon Brando played a teenaged motorcycle gang leader in The Wild One (1953) and epitomized a youthful bike rider with his long sideburns, Perfecto leather jacket, and up-tilted cap—a look so cool Elvis borrowed it two years later for Jailhouse Rock. But until Richard Brooks wrote and directed Blackboard Jungle (1955), about a teacher (Glen Ford) who vies for control of his classroom against inner-city students (led by Sidney Poitier), the troubled lives of teenagers had barely been represented onscreen on their own platform.

Though in a few years a film like Rebel Without a Cause would be a surefire hit and likely B-movie aimed at the burgeoning teenage market, what Ray proposed at the time was risky, if not wholly unprecedented—even more so because Ray wanted to resist representing angst-ridden teenagers as a byproduct of the inner-city ghettos of the period (a belief of the era). Though he was admittedly obsessed with Luis Buñuel’s Los olvidados (1950), a picture about violent Mexico City slum kids, Ray wanted to tap into the consciousness of middle-class America. Receptive to Ray’s ideas, Wasserman spoke with Jack Warner’s top executive Steve Trilling, who wanted to develop the teenage demographic but had not yet found the right picture to do so. Trilling sent several scripts to Ray and with them, a copy of a nonfiction book by Robert Lindner called Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath. Lindner’s position piece on a criminal subject named “Harold” explored the mind of a teenaged criminal through psychoanalysis and defended middle-class delinquents as rebels against social conformity. Nevertheless, Ray had his own ideas; he passed on Trilling’s proposed scripts and tossed Lindner’s book aside. He resolved to write his own 17-page treatment entitled “The Blind Run”, which opened with staggeringly graphic introductions for its teenage characters, all based on actual events: one teen boy sets a man on fire and watches as his victim burns; three teen boys strip down and whip a young girl; two teen drivers race down a dark tunnel toward one another, hence the title “The Blind Run”. Ray’s treatment went on to explore the tragic defiance in a teenaged trifecta, a makeshift family of friends named Jimmy, Eve, and Demo—later to become Rebel Without a Cause’s Jim, Judy, and Plato.

Though in a few years a film like Rebel Without a Cause would be a surefire hit and likely B-movie aimed at the burgeoning teenage market, what Ray proposed at the time was risky, if not wholly unprecedented—even more so because Ray wanted to resist representing angst-ridden teenagers as a byproduct of the inner-city ghettos of the period (a belief of the era). Though he was admittedly obsessed with Luis Buñuel’s Los olvidados (1950), a picture about violent Mexico City slum kids, Ray wanted to tap into the consciousness of middle-class America. Receptive to Ray’s ideas, Wasserman spoke with Jack Warner’s top executive Steve Trilling, who wanted to develop the teenage demographic but had not yet found the right picture to do so. Trilling sent several scripts to Ray and with them, a copy of a nonfiction book by Robert Lindner called Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath. Lindner’s position piece on a criminal subject named “Harold” explored the mind of a teenaged criminal through psychoanalysis and defended middle-class delinquents as rebels against social conformity. Nevertheless, Ray had his own ideas; he passed on Trilling’s proposed scripts and tossed Lindner’s book aside. He resolved to write his own 17-page treatment entitled “The Blind Run”, which opened with staggeringly graphic introductions for its teenage characters, all based on actual events: one teen boy sets a man on fire and watches as his victim burns; three teen boys strip down and whip a young girl; two teen drivers race down a dark tunnel toward one another, hence the title “The Blind Run”. Ray’s treatment went on to explore the tragic defiance in a teenaged trifecta, a makeshift family of friends named Jimmy, Eve, and Demo—later to become Rebel Without a Cause’s Jim, Judy, and Plato.

Trilling was intrigued by Ray’s treatment but understandably believed it far too graphic, although Ray’s ideas were just the kind of sensationalism the studio was looking for. Ray had never been an adept screenwriter; he was better at developing ideas that a writer would then put into a strong narrative. While the studio demanded a professional screenwriter, Ray secured himself a non-negotiable original story credit. This way, no matter how many screenwriters came on board, Ray’s input would remain in the finished film’s credits. For his biggest salary yet, Ray earned $5,000 for “The Blind Run” and $3,000 a week as director. When Warner Bros. officially announced their deal with Ray, they called the project Rebel Without a Cause—a title which Ray disapproved of in favor of his own. Throughout the remainder of the production, Ray jealously fought for the film’s integrity and his vision, losing the occasional battle but winning the war. Most important to Ray was capturing feelings onscreen which he hadn’t been able to communicate in his previous films, feelings of disdain toward his father and regrets about his own failures as a parent. (Ray was estranged from his sons Tony and Tim. Tony, the eldest child from his first marriage, bedded his stepmother Gloria Grahame, Ray’s second wife, in a highly publicized scandal). The simple notion of putting so much of himself onscreen immersed him into the project to a degree he had never known before. He even set up the production at his home at his Chateau Marmont bungalow on Sunset Boulevard, where he would later hold screenwriting conferences and read-throughs with the cast.

Warner Bros. assigned old-hand producer David Weisbart and screenwriter Leon Uris (a studio writer who adapted his own semiautobiographical book Battle Cry into a moneymaking script) to work with Ray on the project, and together they thoroughly researched their subject. Everyone involved believed an accurate depiction of teen violence and angst would help thwart inevitable criticisms of the edgy film. And so Ray, Uris, and Weisbart interviewed judges, child psychologists, social workers, and the juvenile police unit about trends in juvenile delinquency. Ray alone spent a reported 65 hours in a juvenile division police car, according to Warner’s oft-exaggerated publicity department. He even arranged for his young looking 25-year-old nephew Sumner Williams to be arrested and placed in a juvenile detention center, all staged of course, so Sumner could talk with actual young inmates for research. Their most useful source of information, however, would become a local youth gang known as the “Athenians”, some of whom appear in the finished film and helped select cars, clothes, and lend a sense of authenticity to the knife fights and teen camaraderie. At the same time, Ray sought an “exploitation campaign” to announce Rebel Without a Cause as “fresh, different and as realistic as the headlines.” Ultimately, Uris was fired after proposing an idea about a town called “Rayfield” in which small-town America is rocked by a rash of teen crime. The idea and title, named after its director, “made me vomit,” Ray once said. Ray was an auteur, but not so self-important as to exalt himself within the film’s title.

Warner Bros. assigned old-hand producer David Weisbart and screenwriter Leon Uris (a studio writer who adapted his own semiautobiographical book Battle Cry into a moneymaking script) to work with Ray on the project, and together they thoroughly researched their subject. Everyone involved believed an accurate depiction of teen violence and angst would help thwart inevitable criticisms of the edgy film. And so Ray, Uris, and Weisbart interviewed judges, child psychologists, social workers, and the juvenile police unit about trends in juvenile delinquency. Ray alone spent a reported 65 hours in a juvenile division police car, according to Warner’s oft-exaggerated publicity department. He even arranged for his young looking 25-year-old nephew Sumner Williams to be arrested and placed in a juvenile detention center, all staged of course, so Sumner could talk with actual young inmates for research. Their most useful source of information, however, would become a local youth gang known as the “Athenians”, some of whom appear in the finished film and helped select cars, clothes, and lend a sense of authenticity to the knife fights and teen camaraderie. At the same time, Ray sought an “exploitation campaign” to announce Rebel Without a Cause as “fresh, different and as realistic as the headlines.” Ultimately, Uris was fired after proposing an idea about a town called “Rayfield” in which small-town America is rocked by a rash of teen crime. The idea and title, named after its director, “made me vomit,” Ray once said. Ray was an auteur, but not so self-important as to exalt himself within the film’s title.

While seeking another writer to replace Uris, Ray had heard stories about James Dean, a moody, lonely, unstable, but incredibly talented 23-year-old method actor who had just finished making East of Eden with Ray’s friend Elia Kazan. Similar to Kazan’s approach as a director, Dean sought truth in his art and life. Dean was a Midwesterner like Ray, born in Indiana, and he too lost a parent at a young age. As Ray witnessed in a rough cut of Kazan’s film, Dean contained a warmth about him reminiscent of Montgomery Clift, but also a ferocity matched only by the period’s young Marlon Brando, a combustible style that would be perfect for Jim Stark. Ray and Dean met briefly at the early screening of East of Eden but barely spoke. Days later, Dean shambled into Ray’s office, seemingly for no reason at all except to size up the director. Such awkward drop-ins became frequent, the actor never mentioning his desire to perform in Rebel Without a Cause outright, though they had talked about the film’s concept at length. Ray even joined Dean and his friends on late night outings, where Dean further tested his director. Ray later compared Dean to a Siamese cat, saying “The only thing to do with a Siamese cat is to let it take its own time. It will come up to you, walk around you, smell you. If it doesn’t like you, it will go away again. If it does, it will stay.” But then, Ray was a Siamese cat too, whose presence was elusive yet, according to many, “intense”. He and Dean lingered around one another, but the director never offered him the part until the actor confessed his desire to play it (during a trip to a pharmacy where Ray helped Dean secure medication for a case of crabs no less).

For their second screenwriter, Ray and Weisbart hired Irving Shulman, author of the Brooklyn teen gang novel The Amboy Dukes (1946). Shulman had read an article about a “chicken run”, a teenage rite of passage similar to Ray’s “blind run”, and incorporated it into the screen story. Shulman also suggested that the film’s teenage trifecta should meet at a planetarium. But in due course, Shulman was fired after disagreeing with Ray on the narrative’s climax. Ray found his final screenwriter at a Christmas party held by Gene Kelly. Stewart Stern, the Oscar-nominated writer for Teresa (1951), had also met Dean at a different Christmas party where, bored, the writer and actor began to spin in chairs and imitate cows. “His ‘moo’ in Rebel is a souvenir of that—a kind of private hello to me,” Stern remembered. Ray, Dean, and Stern were all cut from the same cloth in their feelings of disappointment in their parents. For example, Jim’s dominant mother and submissive father were based on Stern’s own parents. The scene where Jim’s father wears a flowery apron was based on an incident from Stern’s youth which he never forgot. (Could anyone?) Moreover, Stern gave the teen characters life. In his research he spent time in a juvenile detention center posing as a Wisconsin social worker; there he met a girl whose father wouldn’t let her wear makeup or dress pretty. He found Judy, who goes looking for company in other men to punish her father. Stern and Ray shared the notion that much of the film exists in the fantastical mind of a teenager. In early production notes, Ray even wanted to form sequences with two simultaneous elements, one based in reality and the other based in Buñuel-inspired sequences of surreal fantasy from the teenage perspective. Fortunately, Stern and Ray had a strong enough working relationship that the writer could oppose the director’s ideas without being sacked. In another way, Stern enhanced the fantasy elements of the story, modeling the trifecta on J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan stories, complete with Plato as the Lost Boys, Judy as the innocent and motherly Wendy, and Jim as the magical Peter. Together they go to a mansion Never-Never Land and form their own family away from home.

For their second screenwriter, Ray and Weisbart hired Irving Shulman, author of the Brooklyn teen gang novel The Amboy Dukes (1946). Shulman had read an article about a “chicken run”, a teenage rite of passage similar to Ray’s “blind run”, and incorporated it into the screen story. Shulman also suggested that the film’s teenage trifecta should meet at a planetarium. But in due course, Shulman was fired after disagreeing with Ray on the narrative’s climax. Ray found his final screenwriter at a Christmas party held by Gene Kelly. Stewart Stern, the Oscar-nominated writer for Teresa (1951), had also met Dean at a different Christmas party where, bored, the writer and actor began to spin in chairs and imitate cows. “His ‘moo’ in Rebel is a souvenir of that—a kind of private hello to me,” Stern remembered. Ray, Dean, and Stern were all cut from the same cloth in their feelings of disappointment in their parents. For example, Jim’s dominant mother and submissive father were based on Stern’s own parents. The scene where Jim’s father wears a flowery apron was based on an incident from Stern’s youth which he never forgot. (Could anyone?) Moreover, Stern gave the teen characters life. In his research he spent time in a juvenile detention center posing as a Wisconsin social worker; there he met a girl whose father wouldn’t let her wear makeup or dress pretty. He found Judy, who goes looking for company in other men to punish her father. Stern and Ray shared the notion that much of the film exists in the fantastical mind of a teenager. In early production notes, Ray even wanted to form sequences with two simultaneous elements, one based in reality and the other based in Buñuel-inspired sequences of surreal fantasy from the teenage perspective. Fortunately, Stern and Ray had a strong enough working relationship that the writer could oppose the director’s ideas without being sacked. In another way, Stern enhanced the fantasy elements of the story, modeling the trifecta on J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan stories, complete with Plato as the Lost Boys, Judy as the innocent and motherly Wendy, and Jim as the magical Peter. Together they go to a mansion Never-Never Land and form their own family away from home.

Casting proved even more extensive than finding a writer. Hundreds of young actors auditioned, gathering around Ray’s bungalow where his production operations were based. Natalie Wood, 16, auditioned for the role of Judy and she was determined to get the part. Already a popular child star, Wood had played Dean’s crush in a 1954 television drama called I’m a Fool but wanted to create a more mature image for herself. She dressed up to look more adult and, as a result, Ray passed on her audition. Later, Ray saw a friend of Wood’s, a boy with a scar on his face, and then he reconsidered his decision, thinking perhaps there was more to her after all, a bad girl under her presentable façade. In time, Ray and Wood began an affair. Among the other castmembers was young Dennis Hopper, who didn’t yet know what role he was assigned because the script was still being written, but he was assured a part under his studio contract. Hopper was having an affair with Wood as well, but when Hopper interrupted Ray and Wood together, Ray’s status as the film’s director won out and Hopper was instructed to no longer pursue Wood (by the actress’ parents). Meanwhile, during months of preparation, Ray and Dean spent countless hours together, getting to know one another, forming the father-son bond that would make their working relationship unique and would help transform Dean into the living embodiment of Jim Stark. With only two weeks before filming was set to begin, Ray finally cast Plato. Sal Mineo was a known homosexual, and Ray often sought out bisexual and homosexual actors, not only to align himself with familiar company, but in this case to borrow a cue from Lindner’s book which argued rather naively that criminal behavior in teens was often a result of alienated or “deviant” sexuality. Dean took Mineo under his wing and encouraged Mineo to look at him the same way that Jim looks at Judy, creating the film’s strange father-son sexual tension between the two.

Filming began March 25, 1955 and continued until May 27. Warner Bros. wanted Rebel Without a Cause shot in black-and-white and on CinemaScope at the outset, color being too expensive and reserved for prestige pictures. Behind the camera was Ernest Haller, the Oscar-winning cinematographer of Gone with the Wind. Haller worked closely with Ray to help the director with his first use of the new CinemaScope format. But Ray was a quick study and soon began to develop new shots and angles for his widescreen frame, employing cranes, tilted angles, and a turbulent style to reflect the film’s subject. In the coming years, Ray would use CinemaScope again and again; European cinéastes soon called him “Mr. CinemaScope” because his compositions were unlike anything else on the screen. Meanwhile, Kazan’s East of Eden starring Dean had been released on March 9 in color and enthusiastic responses led the studio to make a last-minute switch from black-and-white to “WarnerColor”. As a result, several scenes required reshoots and Ray had to design an entirely new layer to his melodrama through his use of color. The expressiveness of his color designs in Rebel Without a Cause has only been matched by fellow melodramatist Douglas Sirk (All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind). To accentuate the film’s themes, Ray muted the colors and clothing of adults and augmented those of the teens, especially his teen trifecta: Dean’s bright red nylon jacket would serve as a fiery “warning” of his kinetic emotional state, whereas Wood’s reds and pinks implied her welcoming, supple sexuality. Unlike his more certain friends, his veritable parental figures, Plato’s confused sexuality and identity put him in tweeds and mismatched socks.

Filming began March 25, 1955 and continued until May 27. Warner Bros. wanted Rebel Without a Cause shot in black-and-white and on CinemaScope at the outset, color being too expensive and reserved for prestige pictures. Behind the camera was Ernest Haller, the Oscar-winning cinematographer of Gone with the Wind. Haller worked closely with Ray to help the director with his first use of the new CinemaScope format. But Ray was a quick study and soon began to develop new shots and angles for his widescreen frame, employing cranes, tilted angles, and a turbulent style to reflect the film’s subject. In the coming years, Ray would use CinemaScope again and again; European cinéastes soon called him “Mr. CinemaScope” because his compositions were unlike anything else on the screen. Meanwhile, Kazan’s East of Eden starring Dean had been released on March 9 in color and enthusiastic responses led the studio to make a last-minute switch from black-and-white to “WarnerColor”. As a result, several scenes required reshoots and Ray had to design an entirely new layer to his melodrama through his use of color. The expressiveness of his color designs in Rebel Without a Cause has only been matched by fellow melodramatist Douglas Sirk (All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind). To accentuate the film’s themes, Ray muted the colors and clothing of adults and augmented those of the teens, especially his teen trifecta: Dean’s bright red nylon jacket would serve as a fiery “warning” of his kinetic emotional state, whereas Wood’s reds and pinks implied her welcoming, supple sexuality. Unlike his more certain friends, his veritable parental figures, Plato’s confused sexuality and identity put him in tweeds and mismatched socks.

Ray maintained a master’s control, but not through the traditional means of storyboarding scenes or meticulous on-set dominance; rather, Ray commanded Dean and the rest of the younger performers as a father figure. Once they recognized Ray as a self-styled outsider whose offbeat qualities earned him the reputation as one of the gang, he became the trusted father of the production’s own youth gang. Ray held late-night parties at the Chateau Marmont attended almost exclusively by the younger actors; the older performers playing Jim’s parents, Ann Doran and Jim Backus, felt excluded and didn’t understand this adolescent collective. Ray’s greatest challenge and display of restraint came with Dean. While developing a mutual trust, both men had to explore the natures of one another as well as the story, overcoming their profound uncertainties before baring the degree of emotion unveiled in the film. At one point during the early development stages, Ray’s friend, the writer Clifford Odets, suggested Ray “find the keg of dynamite [Jim is] sitting on.” Both Ray and Dean had desired a better relationship with their fathers, and knowing this Ray used his elder position to transform himself into Dean’s father figure during the production, though as Ray later admitted Dean was “intensely determined to not be loved or to love.” Recognizing this in Dean, Ray manipulated his actors by taking a step back and providing conditions in which they could find themselves within their characters and offer genuine performances. They trusted their director and could be themselves around him. Dean was so unhindered that he was thought to control the set, demanding on more than one occasion that Ray not cut when he’s “in the moment” during a scene. But Dean was temperamental in a manageable way, exploding on-set in moments of outrage and improvisation, with Ray determined not to break the actor’s stride and allow him incredible freedom, enough so that years later costar Hopper claimed that Dean co-directed the picture. Except, Ray’s masterful manipulation of his young cast allowed Dean’s behavior and encouraged it for the film; he even supported Dean’s image by showing up on-set in Jim Stark’s white t-shirt, jeans, and bare feet—a rare sight for a Hollywood director.

Rebel Without a Cause opened on October 26 at a New York City world premiere, and later went on to be a major performer for Warner Bros. Intermittent criticisms stated that the film went to “unacceptable extremes” and was too melodramatic, but overall the reviews were positive. More enthusiastic were the audiences’ reactions, specifically those in the teenage demographic who helped turn the film and James Dean into a cultural phenomenon. To be sure, the film’s success was bittersweet and certainly enhanced by Dean’s death, a mere month before the premiere. On September 30, 1955, Dean smashed his silver Porsche 550 Spyder into a turning Ford in the middle of an intersection and died on the scene. He was just 24. Even though his last screen appearance would be in the Warner Bros. production of George Stevens’ Giant in 1956, Dean would be forever remembered as the epitome of “cool” for playing Jim Stark, his death in a high-speed car crash oddly mirroring Stark’s own fondness for fast cars and near-death experiences onscreen. The actor confessed in an interview, “[Rebel Without a Cause] used me up. I could never take so much out of myself again.” As his enduring pop-culture image would imply, James Dean was Jim Stark, his death having immortalized his own legacy and that of the film. The year after its release, Dean earned a posthumous Best Actor Oscar nomination not for Rebel Without a Cause but for East of Eden; Dean would receive another posthumous Oscar nod for Giant. Ray, who later said Rebel Without a Cause was his favorite of his own works, was less pleased about the film at the time than disturbed about Dean’s death.

Rebel Without a Cause opened on October 26 at a New York City world premiere, and later went on to be a major performer for Warner Bros. Intermittent criticisms stated that the film went to “unacceptable extremes” and was too melodramatic, but overall the reviews were positive. More enthusiastic were the audiences’ reactions, specifically those in the teenage demographic who helped turn the film and James Dean into a cultural phenomenon. To be sure, the film’s success was bittersweet and certainly enhanced by Dean’s death, a mere month before the premiere. On September 30, 1955, Dean smashed his silver Porsche 550 Spyder into a turning Ford in the middle of an intersection and died on the scene. He was just 24. Even though his last screen appearance would be in the Warner Bros. production of George Stevens’ Giant in 1956, Dean would be forever remembered as the epitome of “cool” for playing Jim Stark, his death in a high-speed car crash oddly mirroring Stark’s own fondness for fast cars and near-death experiences onscreen. The actor confessed in an interview, “[Rebel Without a Cause] used me up. I could never take so much out of myself again.” As his enduring pop-culture image would imply, James Dean was Jim Stark, his death having immortalized his own legacy and that of the film. The year after its release, Dean earned a posthumous Best Actor Oscar nomination not for Rebel Without a Cause but for East of Eden; Dean would receive another posthumous Oscar nod for Giant. Ray, who later said Rebel Without a Cause was his favorite of his own works, was less pleased about the film at the time than disturbed about Dean’s death.

To this day, Rebel Without a Cause remains powerful and incredibly relevant in the feelings of teenage displacement and uncertainty in the American Family, albeit through the film’s delicious and intentional overstatement. Realism, after all, has no place in teenage emotions. Certainly, there are moments that feel exaggerated, such as Plato confessing to Jim “If only you could have been my father…” or Mr. Stark saying, “Stand up, son, and I’ll stand up with you. Let me try to be as strong as you want me to be.” Such dialogue underlines the film’s themes with a degree of flamboyance best represented in great melodramas of the 1950s. Other touches are more subtle. At one point, Plato, arguably the first homosexual teenager in cinema, asks Jim to sleep over: “We could talk in the morning and we could have breakfast.” Roger Ebert believed Ray didn’t know what he was trying to say with the film, “Like its hero, Rebel Without a Cause desperately wants to say something and doesn’t know what it is.” Although Ebert grants that perhaps Ray and Shulman “guessed that some of the film’s implications would not be fully recognized by 1955 audiences,” he seems to miss how Ray was more interested in developing and representing teenage emotions onscreen, and not necessarily putting a fine point on what they mean. Ray’s film is about a teenager’s basic need to act out because of the emotional longings and desperate conditions created by a deficient, American middle-class family, where the sole reason behind acting out is because the family is unhealthy. Lucid messages or behaviors have no place here.

In doing this, Ray’s style is theatrical and expressive. His colors are bold, his choice of camera angles dynamic and filled with turmoil. Consider the scene on the staircase where Jim confesses to his parents that he was involved in Buzz’s death, the angle tilted to the right with Jim in-between his parents both literally and metaphorically. Ray’s staging was genius, and he could draw out performances that are at once natural and exaggerated, such as Dean’s iconic, tortured wail: “You’re tearing me apart! You say one thing, he says another, and everybody changes back again!” Ray also incorporates moments of quiet poetry. When Jim and Judy first meet, he asks her “You live here, don’t you?” She responds, “Who lives?” A moment such as this feels uncharacteristic for an American B-movie and more at home in the films of French Poetic Realists like Jean Renoir (Grand Illusion) or Marcel Carné (Children of Paradise)—no wonder the French lauded Ray over all other American auteurs. To tap into his teenage audience and his own lasting memories from his displaced youth, Ray represents the film’s parents as clueless, the failed fathers usually to blame. And to further lyricize Rebel Without a Cause, he encapsulates the entire story within the expanse of a single day, with the introduction of the teen trifecta’s “family” at the police station and their tragic end at the planetarium—where we’ve learned all things are circular, occurring and recurring, beginning and ending over and over into eternity. Families are the same way, never complete, always changing, always repeating themselves, the children making the same mistakes as their parents.

In doing this, Ray’s style is theatrical and expressive. His colors are bold, his choice of camera angles dynamic and filled with turmoil. Consider the scene on the staircase where Jim confesses to his parents that he was involved in Buzz’s death, the angle tilted to the right with Jim in-between his parents both literally and metaphorically. Ray’s staging was genius, and he could draw out performances that are at once natural and exaggerated, such as Dean’s iconic, tortured wail: “You’re tearing me apart! You say one thing, he says another, and everybody changes back again!” Ray also incorporates moments of quiet poetry. When Jim and Judy first meet, he asks her “You live here, don’t you?” She responds, “Who lives?” A moment such as this feels uncharacteristic for an American B-movie and more at home in the films of French Poetic Realists like Jean Renoir (Grand Illusion) or Marcel Carné (Children of Paradise)—no wonder the French lauded Ray over all other American auteurs. To tap into his teenage audience and his own lasting memories from his displaced youth, Ray represents the film’s parents as clueless, the failed fathers usually to blame. And to further lyricize Rebel Without a Cause, he encapsulates the entire story within the expanse of a single day, with the introduction of the teen trifecta’s “family” at the police station and their tragic end at the planetarium—where we’ve learned all things are circular, occurring and recurring, beginning and ending over and over into eternity. Families are the same way, never complete, always changing, always repeating themselves, the children making the same mistakes as their parents.

The degree of feeling articulated in Rebel Without a Cause could only be realized by someone like Nicholas Ray, who identified with these characters and their bold emotions because he understood them and carried these feelings with him his entire life and career. He understood that bringing such drama to the screen by way of young actors required him not to be a domineering director, but a confidant and trusted father figure, a replacement for his cast’s own inadequate parents. To achieve this, Ray created families both onscreen and off, through a profound grasp of his film’s subject matter and a communal production that was perhaps unlike any before in Hollywood. And with this unlikely method, Ray captured lightning in a bottle, a film which endures as an important cinematic landmark yet still contains undeniable relevance. But it’s also a motion picture surrounded by mystique, that of its wonderfully juxtaposed moments of impassioned stylization and emotional realism, and furthermore the respective legacies its director and star. Nicholas Ray and James Dean were outsiders who together made a film that recognizes how we all feel like outsiders sometimes, and through them, Rebel Without a Cause stands as a potent expression of teen angst still vital today.

Bibliography:

Eisenschitz, Bernard. Nicholas Ray: An American Journey. University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

McGilligan, Patrick. Nicholas Ray. New York: HarperCollins, 2011.

Rathgeb, Douglas L. The Making of Rebel Without a Cause. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review