The Definitives

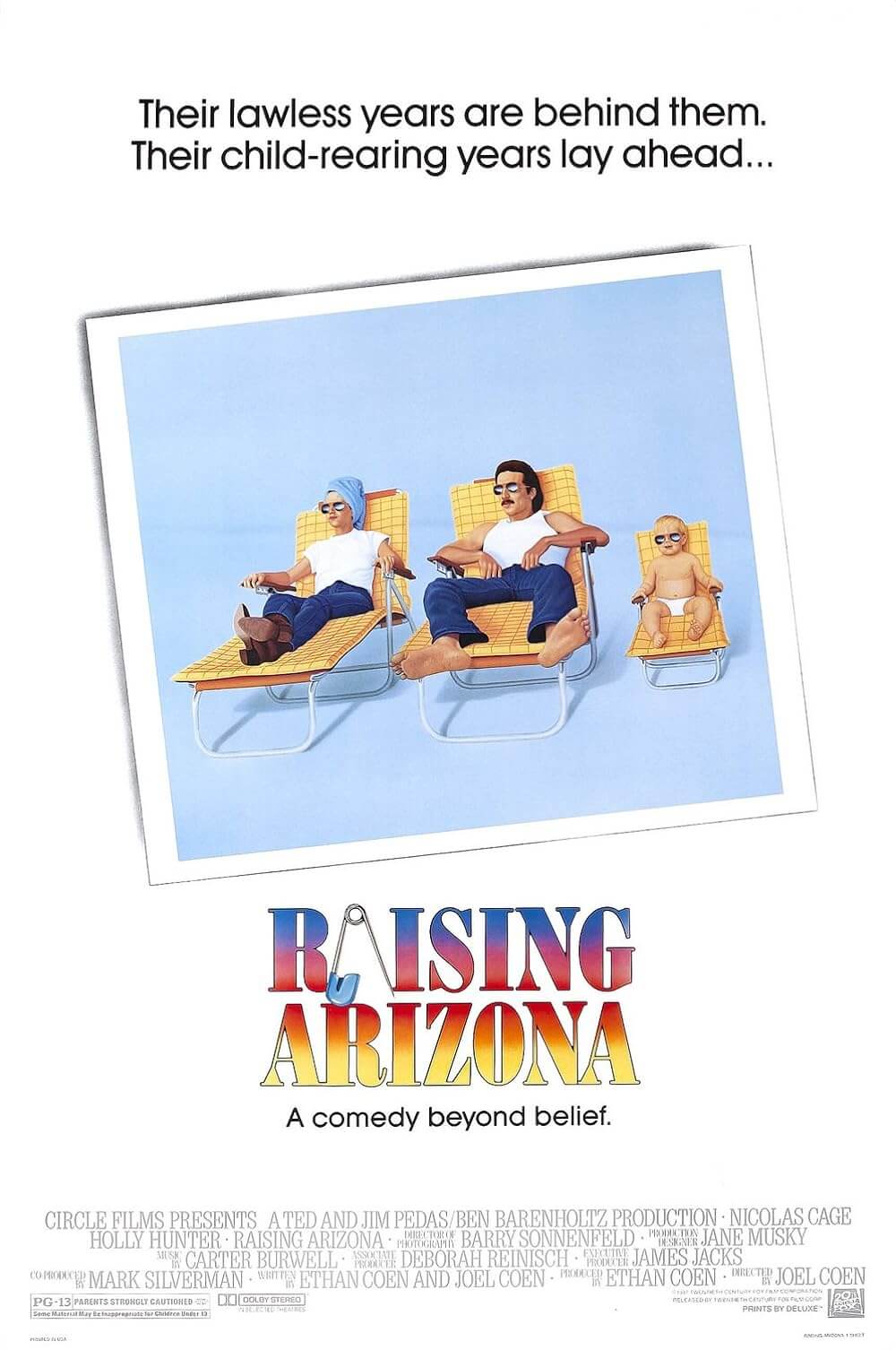

Raising Arizona (1987)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Told in a series of pondering dreams that manifest into horrible realities, circular patterns of behavior, and violence this side of a Looney Tune, Raising Arizona is a film that questions the desire to achieve the ideal American family. The contemplative hero, Nicolas Cage’s frequent convict H.I. McDunnough, hopes to escape his orbit between jail and freedom when he resolves to marry Holly Hunter’s police officer named Edwina, a partner seemingly capable of making him drop anchor. Together, they are desperate to settle down and satiate their baby fever. But their desire leads to a criminal scheme that weighs on the film’s beleaguered Wile E. Coyote, whose existential crisis conjures all manner of obstacles; he descends into further crimes and misdemeanors and purges an apocalyptic demon from his deepest, most repressed inner self. Joel and Ethan Coen’s ruminative, exceedingly quotable comedy is also a breathless display of the siblings’ virtuosity as filmmakers, both as technical craftsmen and literate storytellers. Though Raising Arizona is one of their funniest and most accessible films, it is also among their most introspective. What on the exterior appears to be a lighthearted and purely comic picture on their part bears no less philosophical fruit for the discerning viewer than their more obviously serious films.

For their second endeavor into filmmaking, the Coens sought to create something that stood in opposition to their debut, Blood Simple from 1984. Whereas their first effort moved with the deliberate, slow-burning pace of an ice-cold thriller, their next film would have a breakneck speed. The dark neo-noir atmosphere and the Coens’ black-as-pitch sense of humor would be replaced by a bright, hilarious living cartoon, shot in a series of pensive dreams, elaborate chases, and the energy of an animated short. Blood Simple’s characters were merciless, cynical, and self-serving, while those in Raising Arizona yearn for a family and learn, eventually, that they cannot achieve familial bonds through selfishness. If Blood Simple revealed the potential corruption of basic human desire, be it from greed or love, then Raising Arizona exposes the American family as a troubled, imperfect unit, often aspiring to the unattainable American Dream. On the business side, Blood Simple was an early American independent production, seen widely on the festival circuit but hardly at all by mainstream moviegoers before its presence on home video and cable television. Its meager budget of $1.5 million was tripled by the intake, while Raising Arizona cost nearly double what the earlier film made. After all, it was meant to appeal to a broader demographic, and the $6 million production, distributed by Twentieth Century Fox, demonstrated the brothers’ commercial viability with its $22.8 million in box-office receipts.

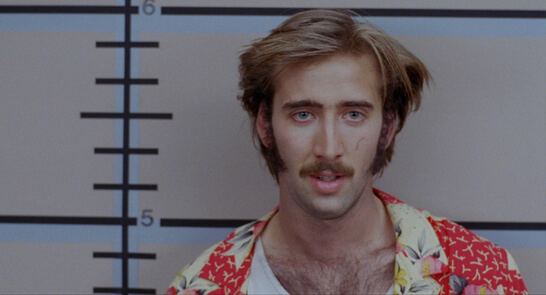

Set in the age of Reaganism and late Cold War paranoia, Raising Arizona concerns H.I. McDunnough, called “Hi” for short. He’s a petty criminal well-versed in robbery with an unloaded gun, and during his rotation in and out of the Maricopa County Maximum Security Correctional Facility in Tempe, he falls in love with a police photographer, Edwina, who goes by “Ed.” Although Ed has a strong maternal desire to raise a family, “biology and the prejudices of others” prevent the couple from having a baby of their own or adopting. Desperate and hopeless, Ed resolves to kidnap an infant after learning that the wife of local unpainted furniture magnate Nathan Arizona has just given birth to quintuplets, and they have “more than they can handle.” And so, Hi and Ed take Nathan Jr. for themselves. But even with a new child, Hi has trouble settling down into domestic life; he’s tempted by the draw of criminality, especially after his former prison mates, Gale and Evelle Snoats (John Goodman and William Forsythe), escape and visit his family. Before long, the Snoats learn about the baby’s identity and resolve to claim a publicized reward. At the same time, a deathly bounty hunter named Leonard Smalls (Randall “Tex” Cobb), either born from or predicted by Hi’s frequent dreaming, appeals to Nathan Arizona, offering to retrieve the stolen child for a hefty price. Just as Hi and Ed recover the child from the Snoats, they face Smalls, who, quite by accident despite his advantage over Hi in combat, dies in a grenade explosion. Resolving to return Nathan Jr., and absolved of any wrongdoing, Hi and Ed sleep on the notion of divorcing, and Hi dreams of a promising future.

Set in the age of Reaganism and late Cold War paranoia, Raising Arizona concerns H.I. McDunnough, called “Hi” for short. He’s a petty criminal well-versed in robbery with an unloaded gun, and during his rotation in and out of the Maricopa County Maximum Security Correctional Facility in Tempe, he falls in love with a police photographer, Edwina, who goes by “Ed.” Although Ed has a strong maternal desire to raise a family, “biology and the prejudices of others” prevent the couple from having a baby of their own or adopting. Desperate and hopeless, Ed resolves to kidnap an infant after learning that the wife of local unpainted furniture magnate Nathan Arizona has just given birth to quintuplets, and they have “more than they can handle.” And so, Hi and Ed take Nathan Jr. for themselves. But even with a new child, Hi has trouble settling down into domestic life; he’s tempted by the draw of criminality, especially after his former prison mates, Gale and Evelle Snoats (John Goodman and William Forsythe), escape and visit his family. Before long, the Snoats learn about the baby’s identity and resolve to claim a publicized reward. At the same time, a deathly bounty hunter named Leonard Smalls (Randall “Tex” Cobb), either born from or predicted by Hi’s frequent dreaming, appeals to Nathan Arizona, offering to retrieve the stolen child for a hefty price. Just as Hi and Ed recover the child from the Snoats, they face Smalls, who, quite by accident despite his advantage over Hi in combat, dies in a grenade explosion. Resolving to return Nathan Jr., and absolved of any wrongdoing, Hi and Ed sleep on the notion of divorcing, and Hi dreams of a promising future.

As with any film by the Coen brothers, the proceedings are more complicated than the surface narrative. Raising Arizona is the sort of film that, if one is lucky enough to have seen it in their youth, grows as one gets older and more mature. What on the surface plays like a screwball farce—chock full of visual gags, hyperbolic performances, hilarious contrasts between the narration and what appears onscreen, and a brilliant rhythmic use of comic timing, supplied by Michael R. Miller’s editing—is a masterwork of technical form and stylistic control. Screwball comedies influenced the brothers, who reference the films of Preston Sturges at various points throughout their career, from their title O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) taken from the name of a highbrow director’s passion project in Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) to the shifting expressions of a painted portrait in their remake of The Ladykillers (2004) drawn from both Sturges and Ernst Lubitsch. In Raising Arizona, the presence of the Arizona quintuplets recalls the octuplets from Sturges’ unbelievably edgy The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), in which a dope named Norval Jones agrees to marry his longtime friend Trudy Kockenlocker when she becomes pregnant after a rowdy party with several men. But the screwball pacing and cartoonish action sequences, informed equally by Sturges and Looney Tunes, easily distract the viewer from its heavier qualities. Note the dark storybook structure and symbolic weight of the material, inspired by the sordid fairy tale quality of a frequent touchstone in the Coens’ body of work, Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) and its meditation on innocence and evil, and how thoughtfully the Coens use these themes to imbue their protagonist with a rich psychological complexity.

In essence, Raising Arizona is about a man stuck in a pattern of behavior, and Hi is the first of many of the Coen brothers’ characters caught in a circular loop, which author Adam Nayman writes about at length. Norville Barnes in The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) starts on the bottom, climbs the corporate ladder, and then hits bottom again, all by the success of his circular invention, the hula hoop. The titular Greenwich Village folk singer of Inside LLewyn Davis (2013) will never become successful because he refuses to change; he remains the author of his own personal and professional failings, caught in an ellipsis signaled in the first and last scenes. In Barton Fink (1991), a New York pseudo-intellectual and playwright determined to serve the everyman with his plays is so wrapped up in the “life of the mind” that, when he moves to Hollywood to write screenplays, he cannot see the everyman right before him. By contrast, only the Dude in The Big Lebowski (1998), who is defined by his lazy routine of bowling, marijuana, and White Russians, is content within his unchanging routine. This circular theme is often accompanied by symbolically circular objects in the Coens’ films, such as the hubcap and UFO of The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001); the coin in No Country for Old Men (2007); the hula hoop of The Hudsucker Proxy; the disc in Burn After Reading (2008); the bowling balls in The Big Lebowski. The Coens also employ a circularity in lesser objects for comic effect, such as how in Raising Arizona a copy of Dr. Spock’s Baby Book passes from the Arizona family to Hi and Ed, then to the Snoats, then back to Hi and Ed, before coming full circle to the Arizonas again.

The larger thematic circularity in Raising Arizona is evident in the way Hi lives in a perpetual revolution, rotating between prison and freedom. In the nearly 10-minute prologue before the title appears onscreen, Hi goes in and out of prison several times. Each time, he sees Ed and flirts, making his intentions known. Each time, she photographs him for a mug shot, ordering him to “Turn to the right” for another angle. It’s as though he keeps turning to the right and continues to go in circles. And each time, he convinces an impressionable parole board that he’s ready to reform. With an “Okay then,” they release him, but not without a lecture: “Got a name for people like you, Hi. That name is called recidivism.” Not long after he affirms that he’s no repeat offender, though, Hi has returned to prison, captured for yet another robbery with an unloaded gun. In the group counseling sessions provided by the prison psychologist, inmates talk of feeling “trapped” by the exterior world. But inside, there’s “a spirit of camaraderie that exists between the men, like you find only in combat maybe,” observes Hi. His statement is contrasted by an inmate that snarls at Hi as he passes. Hi seems drawn to confinement less out of his institutionalization or unpreparedness for the world outside of prison, and more out of a sense of feeling trapped by the world at large. What could be so awful outside of prison to make the company of snarling prisoners preferable? Perhaps it’s his own failure to live up to the ideals of the American family.

The larger thematic circularity in Raising Arizona is evident in the way Hi lives in a perpetual revolution, rotating between prison and freedom. In the nearly 10-minute prologue before the title appears onscreen, Hi goes in and out of prison several times. Each time, he sees Ed and flirts, making his intentions known. Each time, she photographs him for a mug shot, ordering him to “Turn to the right” for another angle. It’s as though he keeps turning to the right and continues to go in circles. And each time, he convinces an impressionable parole board that he’s ready to reform. With an “Okay then,” they release him, but not without a lecture: “Got a name for people like you, Hi. That name is called recidivism.” Not long after he affirms that he’s no repeat offender, though, Hi has returned to prison, captured for yet another robbery with an unloaded gun. In the group counseling sessions provided by the prison psychologist, inmates talk of feeling “trapped” by the exterior world. But inside, there’s “a spirit of camaraderie that exists between the men, like you find only in combat maybe,” observes Hi. His statement is contrasted by an inmate that snarls at Hi as he passes. Hi seems drawn to confinement less out of his institutionalization or unpreparedness for the world outside of prison, and more out of a sense of feeling trapped by the world at large. What could be so awful outside of prison to make the company of snarling prisoners preferable? Perhaps it’s his own failure to live up to the ideals of the American family.

If Ed’s repeated order to “Turn to the right,” thus spinning Hi, is symbolic of his circular pattern between freedom and prison, it also hints at the United States’ turn toward right-wing politics and the reintegration of family values under Ronald Reagan and his slogan, “Let’s Make America Great Again.” Several brief references to Reagan and the results of his trickle-down economics suggest that Hi blames hardships propelled by the Reagan era for his troubles. “I tried to stand up and fly straight,” he admits in voiceover. “It wasn’t easy with that sumbitch Reagan in the White House. I dunno. They say he’s a decent man, so maybe his advisors are confused.” During Reagan’s administration, the gap between the rich and the poor widened, while incarceration rates skyrocketed after his Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986, landing hundreds of thousands of non-violent offenders in prison. The effect is disenchanting for Hi, who secures himself a grimy factory job, stationed next to M. Emmet Walsh’s ear-bender. He goes to cash his check and, as he looks at it disappointedly, the teller remarks, “The government do take a bite, don’t she?” In contrast to the outside world, the structure of prison life at least affords some predictability in the reliable two meals a day and roof over one’s head. Elsewhere, a right-leaning politician, “one of Dick Nixon’s undersecretaries of agriculture,” whom Gale and Evelle Snoats meet in prison, gives them a tip to rob a Hayseed bank, suggesting the political right continues to rob the lower classes even from jail. Alternatively, Hi’s prison bunkmate has a photo of JFK taped to the wall, representing a decided contrast to Reaganism. The effect of these partisan motifs in Raising Arizona points to the film’s subjective viewpoint that those inside prison have an enemy in the right, a party that makes it impossible for Hi to reform.

Hi and Ed enter into their marriage with haste, and it’s a union followed by a series of events that, rather than break Hi’s pattern, maintain his rotation. He’s an ex-convict with recidivistic tendencies, and she’s on a vulnerable rebound after her fiancé leaves her. But Ed’s sudden availability, and Hi’s natural attraction to her, combine with the protagonist’s pressure to lead a normal life. “Most men your age are getting married and raising up a family,” the prison counselor tells him. “They wouldn’t accept prison as a substitute.” Determined to break his own circular pattern, Hi proposes to Ed and, after a speedy marriage, they plan to produce a child with whom they can share their “thoughts and feelin’s.” But they quickly learn that Ed is barren, or as Hi puts it, “Her insides were a rocky place where my seed could find no purchase.” Ed is devastated. She stops going to work, gives up on housekeeping, and spends her time staring at baby photos. Both want an American family, and it seems their marriage is lifeless if it doesn’t conform to those ideals. When Ed learns of the Arizona quints (Barry, Harry, Larry, Garry, and Nathan Jr.), the Coens reinforce the Reagan-era socioeconomic divide between the wealthy Arizonas in their Southwestern estate and the McDunnoughs in their trailer, parked seemingly in the middle of a desertous nowhere. Hi justifies “Ed’s little plan” by rationalizing, “We thought it was unfair that some should have so many while others should have so few” —which itself is a remark on Reagan’s Voodoo economic plan.

Unable to live up to the demands of the American Dream, Hi and Ed must resort to crime to approximate it, and in doing so, perhaps the Coens supply a critique of such narrow social expectations. After all, it’s almost as though the universe reaches out to prevent their false, criminal attempt at a so-called complete family unit—something that goes against what Nature has intended for them at this particular moment. Once they nab the Arizona baby (Hi takes “Nathan Jr., I think”), Ed believes everything will be “decent and normal from here on out.” With that, Gale and Evelle Snoats escape from prison and enter the film as if born in opposition to Ed and Hi’s hopes and dreams. It’s a sight that, soaked in rain and mud, has the Snoats screaming like monstrous newborn babies, an antithesis of the Arizona quints, as though the Earth had given birth to them from the anus of the prison sewer. The Snoats barely clean themselves in a gas station bathroom, slick down their hair with handfuls of pomade grease, and make for the home of their former fellow inmate in a stolen car. To be sure, the Snoats represent a temptation for Hi, whose outlaw tendencies have already been re-energized by that night’s crime of kidnapping. Still, if the Snoats threaten to draw Hi back into a life of crime by questioning the dynamics of his marriage when Ed protests their visit (“Say, who wears the pants round here…?” asks Gale), then Smalls infers something more profound and more primeval inside of Raising Arizona’s protagonist.

Unable to live up to the demands of the American Dream, Hi and Ed must resort to crime to approximate it, and in doing so, perhaps the Coens supply a critique of such narrow social expectations. After all, it’s almost as though the universe reaches out to prevent their false, criminal attempt at a so-called complete family unit—something that goes against what Nature has intended for them at this particular moment. Once they nab the Arizona baby (Hi takes “Nathan Jr., I think”), Ed believes everything will be “decent and normal from here on out.” With that, Gale and Evelle Snoats escape from prison and enter the film as if born in opposition to Ed and Hi’s hopes and dreams. It’s a sight that, soaked in rain and mud, has the Snoats screaming like monstrous newborn babies, an antithesis of the Arizona quints, as though the Earth had given birth to them from the anus of the prison sewer. The Snoats barely clean themselves in a gas station bathroom, slick down their hair with handfuls of pomade grease, and make for the home of their former fellow inmate in a stolen car. To be sure, the Snoats represent a temptation for Hi, whose outlaw tendencies have already been re-energized by that night’s crime of kidnapping. Still, if the Snoats threaten to draw Hi back into a life of crime by questioning the dynamics of his marriage when Ed protests their visit (“Say, who wears the pants round here…?” asks Gale), then Smalls infers something more profound and more primeval inside of Raising Arizona’s protagonist.

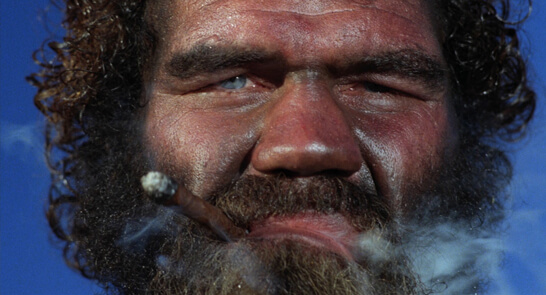

That first night after kidnapping Nathan Jr., after resolving with Ed that the Snoats can stay “just a day or two,” when the possibility of Hi’s familial ambitions and the reality of his criminal impulses teeter-totter in the narrow space of his “starter home,” he has a dream of the yet-unseen Leonard Smalls. A hound of hell with a “Mama didn’t love me” tattoo, and a devotee to the wardrobe choices in The Road Warrior (1982), Smalls appears in Hi’s dream as the protagonist narrates: “He left a scorched earth in his wake, befouling even the sweet desert breeze that whipped across his brow.” But Smalls also exists in the real world, not merely as a product of Hi’s doomed premonition, and he, therefore, initiates Raising Arizona into the realm of magical realism. On Smalls’ real side, the “part bloodhound” bounty hunter attempts to secure a deal with Nathan Arizona, claiming to have tracked down stolen babies before; though, his discussion of this topic suggests he’s not beyond selling children himself. He even claims to have fetched $30,000 on the black market in 1954 when he was a baby. On his more fantastical side, he may be Hi’s dark half come to life, a supernatural character that the protagonist must destroy in a symbolic act in order to settle down into family life. Perhaps Hi was the one born in 1954 and sold on the black market, and perhaps, when the possibility of family life takes over as his primary drive, the criminal part of him separated. If this is the case, when Arizona accuses Smalls of a shakedown, the viewer knows he’s wrong, in a way, because we saw that Hi took the baby. But in another way, Arizona is right; Smalls, or at least the part of him that lived inside of Hi, performed the kidnapping.

If Smalls isn’t a physical manifestation of Hi’s inner criminal, then he’s at least a dramatic symbol of it, an association made by their shared Mr. Horsepower tattoo (often misidentified as Woody Woodpecker). Having seen Smalls in his dream before real-life, Hi certainly believes he has brought Smalls into this world, to the extent that when Ed first acknowledges she sees the “warthog from hell,” Hi responds with a level of affirmed sanity: “Do you see him too?”—as though Hi believed that Smalls existed only in his mind. Given Hi’s belief in their shared connection, the way Hi says “I’m sorry” when he pulls the pin from Smalls’ grenade isn’t spoken with the anger one might have for an enemy. He says the line with genuine regret, as though the act is a goodbye to part of himself. The Coens’ use of a double in this way is not a modern flourish but a classical one. Doppelganger motifs frequently occur in classical literature, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1845 to Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Double the following year, and then Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886. Stephen King even explored the doppelganger two years after the release of Raising Arizona in his novel The Dark Half. As Erica Rowell observes, Raising Arizona springs from a decidedly American Gothic tradition of literary doubles, citing Edgar Allen Poe’s 1839 short story “William Wilson,” about a nobleman and his mischief-making double. But whereas Poe’s protagonist succumbs to his double, a symbolic figure of the character’s own madness, Hi resists and ultimately obliterates his double, a character defined in the Coens’ sound design through animalistic aural touches to underscore the primal quality the conflict. Smalls growls like an underworld beast and, when he eventually detonates by grenade, the sound of a lion roars over Smalls’ obliteration.

If there’s an irony to Hi’s mission in life to become a parent alongside Ed, it’s the unflattering way in which Raising Arizona portrays parenthood and the American Dream through families like the Arizonas or Ed’s friends. The Arizonas live in a massive Southwestern estate and, with their five infants nestled in their extra-long crib upstairs, Nathan contentedly reads a newspaper and enjoys an adult beverage while Mrs. Arizona knits, both on separate planets. Similarly, Ed’s friends Glen (Sam McMurray) and Dot (Frances McDormand) represent what Ed describes as “decent folk” compared to the Snoats. The day after the kidnapping, Glen and Dot arrive for a barbeque at Ed and Hi’s trailer, their five children of varying ages in tow. They’re seemingly a reflection of what Ed desires out of the American family ideal, but it’s hardly appealing to Hi—nor could it be for anyone else, for that matter. Their five Jello-throwing, FART-writing, animal-like children make short work of Hi and Ed’s trailer and vehicle, tearing them apart like gremlins, not that Glen and Dot notice or attempt to stop this behavior. Dot is an exceedingly nosy chatterbox and, before the picnic is through, Glen, who never met a gaudy pattern or dumb-Polack joke he didn’t like, proposes a wife-swapping arrangement to Hi—to which Hi replies by socking Glen in the jaw. “Keep your goddamn hands off my wife!” Out of sheer embarrassment and protection of Ed’s dream for a normal family, Hi cannot be brought to burst her bubble and tell her that Glen and Dot are swingers. Even with negative examples of the American Dream realized before them, Ed and Hi are not dissuaded from trying. “Well, it ain’t Ozzie and Harriet,” Hi resolves.

Hi’s disenchantment with parenting is tantamount to Ed’s unhinged desperation to become a mother, her sole ambition, and a job for which she may have noble intentions but no real skill at first. Physically, she is unable to conceive a child, a wrinkle that is reflected in the couple’s choice of environment. Rather than settling down in the typical suburban utopia of the American family or even around other people, they choose to live secluded in the Arizona desert that reflects her own barren state. Moreover, Ed’s mothering instinct may be strong and pure, but she often makes misguided or self-destructive choices. Her desire for a child, for instance, outweighs any general motherly care for an infant’s safety when she demands that Hi break into the Arizona household and steal one of the quintuplets. But also consider her choice of lullaby for the newly acquired Nathan Jr.—”Down in the Willow Garden,” an Appalachian ballad about a man who plots to poison a young woman, Rose Connelly, but he stabs her and tosses her body in the river instead. The singer hopes his father’s influence will set him free, but he’s sentenced to be hanged. It’s not exactly the musical bedtime balm it should have been. But whatever Ed initially lacks in specific, child-friendly choices, she makes up for in her subsequent undaunting protection of Nathan Jr. after the Snoats, and then later Smalls, steal the baby. “I don’t care about myself anymore,” she declares. “I don’t care about us anymore. I just want Nathan Jr. back safe.” At the outset, her approach to parenting may be unsound, yet she grows into one of the Coens’ selfless noblewoman characters. By the end of Raising Arizona, she belongs alongside Fargo’s Marge Gunderson and No Country for Old Men’s Carla Jean Moss, who are unmovable, virtuous women and do not bend in their integrity when faced with senseless evil in the form of low-level crooks from Fargo and Minneapolis, Anton Chigurh, or the lone biker of the apocalypse.

Watching Raising Arizona, it’s easy to overlook the intricacy of the characters and themes because the Coens and cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld construct such a wild, exciting, and incredibly dynamic formal presentation. Sonnenfeld’s camera observes from almost exclusively high or low angles to capture the film’s topsy-turvy world, a place of extreme mania, where the passion between Hi and Ed is frequently challenged by Hi’s criminal impulses and the unholy monster it invokes. When Hi breaks into the Arizona household to select a child, Sonnenfeld’s roving camera, set low to the floor for a baby’s-eye-view, tracks crawling infants like a predator on the African planes. Sonnenfeld’s whooshing, ever-roving camera movements and the Coens’ perfect comic timing in the editing room reach their zenith not at the climax, but during a chase sequence mid-film. Hi’s assault on Glen in defense of the sanctity of his marriage results in a digression of his character, who responds to Ed’s inevitable scolding for the incident by holding up a convenience store for Huggies diapers and the cash in the register. Thus launches Raising Arizona’s most dazzling sequence, when Hi steals the Huggies from the local Short Stop convenience store and a frantic chase, staged like a cartoon within the corner-turning obstacles of a pinball machine, ensues through the neighborhood. An armed clerk shoots his hand cannon at Hi, cops pursue in a squad car, Ed circles the area with Nathan Jr. in the family car, and a pack of dogs follows the action, sounding like a stampede of raging cattle. It’s all set to the oddly thrilling score of banjos, mouth harp, and John R. Crowder’s yodeling and whistling—composed by Carter Burwell, who has scored nearly every Coen brothers film since their debut on Blood Simple.

Then again, the Huggies chase was inevitable. From the moment Ed sends Hi into the Arizona nursery to capture a child for their own, Hi’s chance to settle down and form an idyllic American family was spoiled. He is thrust back into his circular pattern of behavior the moment he acted to create a family. However, his latest regression into criminality isn’t merely another turn to the right, another brief stint in prison for unarmed robbery, followed by a prompt release. It’s far more primal and consequential, thus dramatic—a turn distinguished by the arrival of Smalls from, possibly, another plane of existence, a physical and symbolic manifestation that could potentially allow Hi to break free of his pattern, in the same way an asteroid could knock a planet out of its orbit. Hi senses this when he plans to leave Ed after the Huggies digression, writing in his goodbye note, “I feel this thunder gathering even now. If I leave, hopefully, it will leave with me.” But the question of whether Hi emerges from his revolutions between criminality and a quiet domestic life remains open-ended. The grand events of Raising Arizona end with Hi and Ed questioning whether they should stay together, a turn that ultimately brings Hi full circle, in the sense that his future is just as uncertain as when the film began. He can either choose to settle down or regress once more into his recidivism. Fortunately, the end of the film leaves Hi’s future open, which is more than can be said of many Coen characters whose circular journeys end with their deaths—as in A Serious Man, The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

Then again, the Huggies chase was inevitable. From the moment Ed sends Hi into the Arizona nursery to capture a child for their own, Hi’s chance to settle down and form an idyllic American family was spoiled. He is thrust back into his circular pattern of behavior the moment he acted to create a family. However, his latest regression into criminality isn’t merely another turn to the right, another brief stint in prison for unarmed robbery, followed by a prompt release. It’s far more primal and consequential, thus dramatic—a turn distinguished by the arrival of Smalls from, possibly, another plane of existence, a physical and symbolic manifestation that could potentially allow Hi to break free of his pattern, in the same way an asteroid could knock a planet out of its orbit. Hi senses this when he plans to leave Ed after the Huggies digression, writing in his goodbye note, “I feel this thunder gathering even now. If I leave, hopefully, it will leave with me.” But the question of whether Hi emerges from his revolutions between criminality and a quiet domestic life remains open-ended. The grand events of Raising Arizona end with Hi and Ed questioning whether they should stay together, a turn that ultimately brings Hi full circle, in the sense that his future is just as uncertain as when the film began. He can either choose to settle down or regress once more into his recidivism. Fortunately, the end of the film leaves Hi’s future open, which is more than can be said of many Coen characters whose circular journeys end with their deaths—as in A Serious Man, The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

After Ed and Hi return Nathan Jr. to the Arizona nursery, the boy’s father offers straightforward advice about the couple’s future, and by consequence, Hi’s fate: he tells them to sleep on it. That night, Hi dreams of his future and sees an old couple, possibly he and Ed, who have raised a family and have grandchildren. “It seemed real,” Hi says in voiceover. “It seemed like us. And it seemed like, well, our home.” But who can be sure? Although Raising Arizona rests on this ambiguous ending, it should be read as full of possibility, even hopeful despite its potential for cynicism. Though his circular behavior could swing to the right once more, the viewer has every reason to believe Hi’s dream will come to pass. His previous dreams came true. Why wouldn’t this one? A clue to Hi’s fate may rest in the narration—not the substance of the voiceover but the words themselves, which present a contrast between the inflated manner of his voiceover (“He was especially hard on the little things, the helpless and gentle creatures”) and the low speak of his on-screen dialogue (“He ain’t too good. You can tell by that twinkle in his eye.”). The narration seems to come from a distant place in the future, where Hi speaks with the learned view of experience, whereas his language in the on-screen action, while overblown, rings unpolished. Could it be that Hi has long since grown up and tells this story to a grandchild on his knee? “You tell me. Was it wishful thinking?” he asks us in the end. I don’t think it was.

Bibliography:

Baz Allen, William Rodney, ed. The Coen Brothers: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Bergan, Ronald. The Coen Brothers. Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2000.

Doom, Ryan P. The Brothers Coen: Unique Characters of Violence. ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2009.

Nayman, Adam. The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together. Harry N. Abrams, 2018.

Palmer, R. Barton. Joel and Ethan Coen. University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rowell, Erica. The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007.

Woods, Paul A., ed, Joel and Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings. Plexus, 2000

(Editor’s Note: Corrected reference to the film’s editor.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review