The Definitives

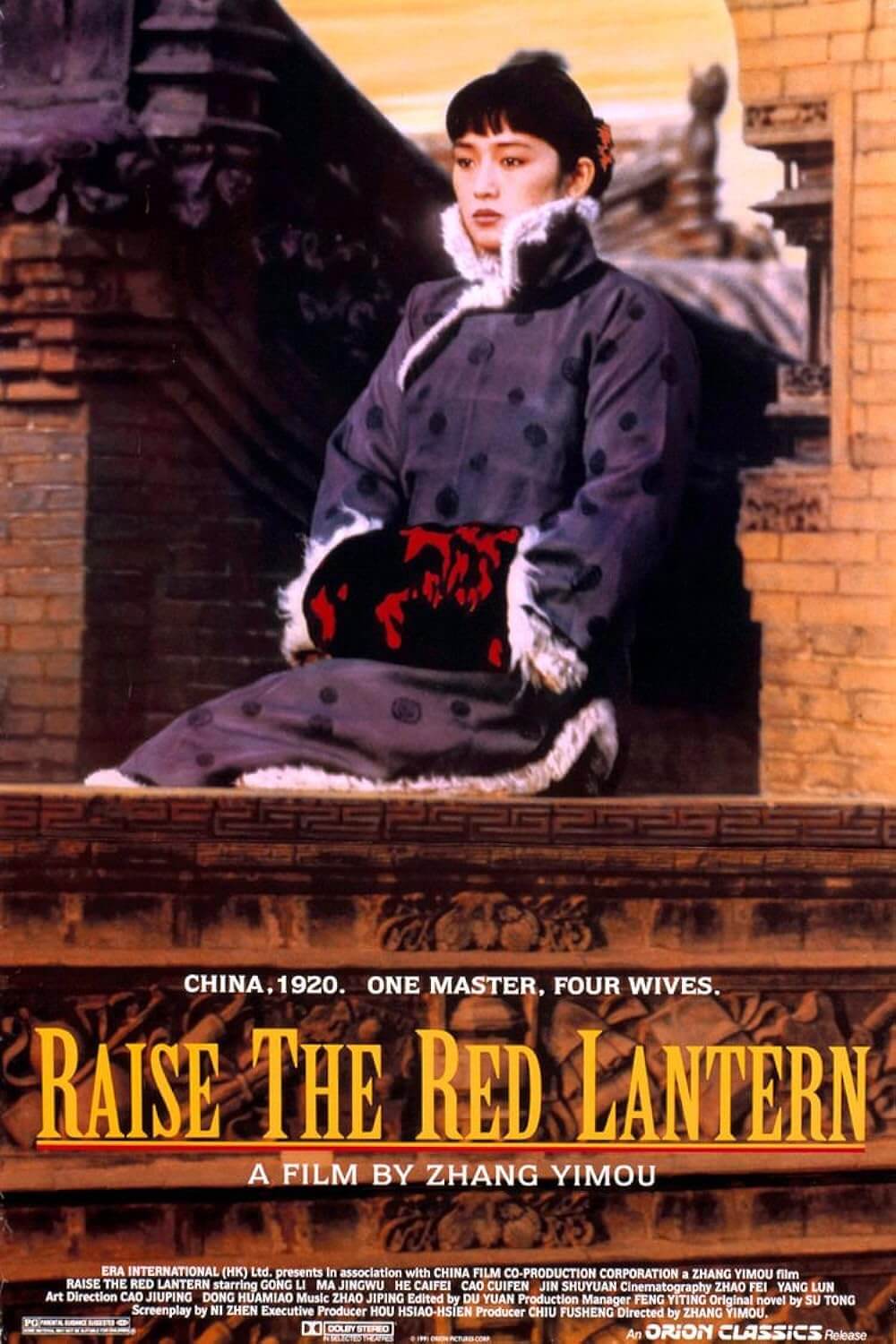

Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Raise the Red Lantern, Zhang Yimou’s most widely acclaimed film, the Chinese director portrays life as a series of performative gestures under the duress of cultural tradition, prescribed gender roles, and hierarchical power structures. Based on the 1987 novella Wives and Concubines by Su Tong, the film depicts a precise historical period to confront how China’s post-Mao era, which claims to have moved beyond its troubling past, remains constrained by purportedly bygone ideological and cultural precepts. Through staggeringly beautiful imagery and a complex central performance by the director’s greatest onscreen collaborator, Gong Li, Zhang portrays women trapped in an intricate competition and dominated by a master who presides over his compound. Whether labeled a wife, concubine, or servant, the women perform a series of rituals and compete for their master’s affection, though their small victories remain illusions in a rigged game. The film reaches into Chinese history to examine an oppressive system in which women become objects and commodities of patriarchal reign. Using allegory, tragedy, and sublime beauty, and guided by his humanist consciousness, Zhang exposes imbalances of power between men and women, the gentry and the underclass, and ultimately his modern government and its citizens, which have been etched in the stone of Chinese culture.

Film writers have extolled the many thematic and visual splendors of Raise the Red Lantern, and there will be some of that here, too. After all, Zhang’s highly structured and intensely dramatic film, released in 1991, makes incredible use of the story’s symbolism. His iconic reds and visualization of oppression in this, the third entry of his unofficial Red Trilogy, preceded by Red Sorghum (1987) and Ju Dou (1990), creates undeniably immaculate imagery. However, the primary focus of this essay concerns how Zhang comments on Chinese philosophy and history, portraying the culture through an allegory in which the traditions of the story’s wealthy estate amount to a manipulative game of fear and desire. Zhang’s early work often urges social change using emblematic methods. In a 1992 interview, Zhang called his approach one of “cultural reflection and cultural awareness” from a “humanist background” and a “necessarily rebellious spirit.” Although the film’s emotional impact is universal, through this exploration of contexts ranging from cultural to historical to cinematic, viewers may more fully engage with the film—not only as an engrossing period drama that captures a specific time and place in China’s history but how it reveals Zhang’s necessary voice as an artist in his contemporary China.

Hewing closely to the original novella, the film tells the story of Songlian (Gong), a young woman of nineteen with six months of university education. Songlian’s father has died, and her stepmother cannot afford to complete her schooling. The first scenes begin after three days of deliberation, when Songlian concedes to marry a rich man at her stepmother’s behest, thus becoming his concubine. Songlian surrenders herself to “a woman’s fate,” a resolution she makes with tearful eyes. However, she marries into a traditionalist family only to buckle against some of its customs. For instance, she walks to her new husband’s compound instead of riding in the sedan he sends for her, and she prefers to carry her own bags instead of giving them to her assigned maid, Yan’er (Kong Lin). She becomes the fourth wife, or third concubine, of Master Chen (Ma Jingwu), and her youth and education bring a new element into the home. Her so-called sisters include the third mistress, Meishan (He Saifei), who once served as an opera singer; the second mistress, Zhuoyun (Cao Cuifen), who appears friendly and considerate to cover her duplicitousness; and the first wife, Yuru (Jin Shuyuan), whom the others call “Big Sister.” Yuru, too old to compete with the concubines, prefers to sit back and observe “such sins.” Along with Songlian, the women serve in a strict competition for Master Chen’s favor and the associated perks. But first, Songlian must go through the process of learning the compound’s game and its rules, and how to adjust her performance to survive. “It’s all play-acting,” Meishan explains later. “The trick is to get good enough to fool yourself.”

The film’s portrait of China’s social hierarchies aligns with those of the country’s leading moral philosopher, Confucius (551-479 BC). His teachings in the Analects, a book compiled by his students, show that he believed in a stratified and patriarchal society in which each member knew their role and place, and each demonstrated their understanding with expected behaviors, granting the Emperor total control over his territory and an intricate line of officiates to carry out his rule. In addition, Confucius believed in familial obedience, particularly to the father and elders, while women and children remained subordinate—the passive yin to the active yang in the family’s dichotomy. Confucius’ family design extended to the larger social structure as well, arranging the patriarchal hierarchy with the Emperor over the gentry class, followed by peasants, and then finally merchants. Confucianism’s morals and values concerning filial piety lasted thousands of years until the Cultural Revolution, when the Communist Party denounced Confucianism, banned the Analects, and targeted its scholars, believing it partly responsible for China’s feudal society and the ruling class. Even so, Confucianism remains such a part of Chinese identity that, despite reforms throughout the Republic of China (1912-1949), the Civil War years, and the modern-day People’s Republic of China, its influence maintains a place in Chinese households, businesses, and politics.

The film’s portrait of China’s social hierarchies aligns with those of the country’s leading moral philosopher, Confucius (551-479 BC). His teachings in the Analects, a book compiled by his students, show that he believed in a stratified and patriarchal society in which each member knew their role and place, and each demonstrated their understanding with expected behaviors, granting the Emperor total control over his territory and an intricate line of officiates to carry out his rule. In addition, Confucius believed in familial obedience, particularly to the father and elders, while women and children remained subordinate—the passive yin to the active yang in the family’s dichotomy. Confucius’ family design extended to the larger social structure as well, arranging the patriarchal hierarchy with the Emperor over the gentry class, followed by peasants, and then finally merchants. Confucianism’s morals and values concerning filial piety lasted thousands of years until the Cultural Revolution, when the Communist Party denounced Confucianism, banned the Analects, and targeted its scholars, believing it partly responsible for China’s feudal society and the ruling class. Even so, Confucianism remains such a part of Chinese identity that, despite reforms throughout the Republic of China (1912-1949), the Civil War years, and the modern-day People’s Republic of China, its influence maintains a place in Chinese households, businesses, and politics.

Confucianist cultural hierarchies were particularly difficult for women, even after the imperial rule of the nearly three-hundred-year Qing Dynasty ended with the 1911 Revolution. Raise the Red Lantern takes place in the 1920s, during the Warlord Period that started in 1916 with the death of Yuan Shikai, the first President of the Republic of China. After Yuan’s death, the country splintered into various factions ruled by military leaders who often supported Confucian values. Under this system, women’s roles remained subject to the same gender and class inequalities from late dynastic times, not to mention subject to the vast marketplace of human beings active in China at the time. However, men could not engage in polygamy to the same extent as they could during the Qing Dynasty. In the early Republic of China, laws were changed to a system of “one husband, one wife.” Concubinage no longer held the same status of legitimate marriage from the Qing period, and a husband could have only one wife legally. The relationship between a man and his concubine was purely transactional, and further, it represented a kind of theater. In Raise the Red Lantern, Master Chen’s household refers to the concubines as “wives,” and the concubines call Master Chen their “husband.” Still, the relationship between them is, officially, a contractual one.

In wealthy households invariably ruled by men, referred to as “master,” women served as wives, concubines, or maids in a strict social ladder. Families arranged marriages for their sons. The wife entered into her husband’s family through a formal process that included passing several rites. The wife’s family supplied the husband with gifts and a dowry, and she joined the family with an elaborate ceremony, including a feast and public celebrations. The wife, then, runs the house and has power over the marginal concubines and maids. Men often purchased concubines from a brothel, a dealer, or, as in the case of Songlian, from parents. Their functions ranged from providing the husband with pleasure to elevating his status, and like wives, any offspring they might produce would be considered legitimate. The household also purchased maids, referred to as “little maids” or “little sisters,” as domestic servants, who typically had no reproductive or sexual responsibilities. Little maids usually served the household until the age of eighteen, at which point they might be sold off or become a concubine. And as Zhang’s film shows, within the household’s hierarchical structure, women compete with one another for the master’s favor to earn certain luxuries and advantages.

Songlian enters the household and must acclimate to Master Chen’s strange house rituals and the competition she faces with her two fellow concubines. Each mistress has her own house within the larger compound, and each day, they must wait at the end of their home’s pathway for a servant to perform his daily task—announcing Master Chen’s choice for that evening by placing a red lantern before the selected mistress. On Songlian’s first day, a servant announces her selection, “Lighting the lanterns of the Fourth House!” The servants then perform the ritualized process of carting red lanterns to the chosen house, removing their coverings, and lighting them. And there are perks to being chosen. The mistress whose home boasts the lanterns selects the menu for the other mistresses, all of whom eat together for every meal. But the most coveted perk entails the maids who wash the chosen mistress’ feet and massage them with two hammer-like rattles. “A woman’s feet are very important,” the Master explains to Songlian on her first night. “When they feel comfortable, she’s healthier and better able to serve her man.” The massages serve another purpose as well; their rattling echoes throughout the compound, reminding the other mistresses what they are missing, that they were not chosen. It’s a regimented and carefully tiered game that affects every interaction. Scholar Wendy Larson observes, “the perpetual need to function constantly within the context of economic value […] has been absorbed into the physical structures and relationships.”

Songlian enters the household and must acclimate to Master Chen’s strange house rituals and the competition she faces with her two fellow concubines. Each mistress has her own house within the larger compound, and each day, they must wait at the end of their home’s pathway for a servant to perform his daily task—announcing Master Chen’s choice for that evening by placing a red lantern before the selected mistress. On Songlian’s first day, a servant announces her selection, “Lighting the lanterns of the Fourth House!” The servants then perform the ritualized process of carting red lanterns to the chosen house, removing their coverings, and lighting them. And there are perks to being chosen. The mistress whose home boasts the lanterns selects the menu for the other mistresses, all of whom eat together for every meal. But the most coveted perk entails the maids who wash the chosen mistress’ feet and massage them with two hammer-like rattles. “A woman’s feet are very important,” the Master explains to Songlian on her first night. “When they feel comfortable, she’s healthier and better able to serve her man.” The massages serve another purpose as well; their rattling echoes throughout the compound, reminding the other mistresses what they are missing, that they were not chosen. It’s a regimented and carefully tiered game that affects every interaction. Scholar Wendy Larson observes, “the perpetual need to function constantly within the context of economic value […] has been absorbed into the physical structures and relationships.”

Although the daily selection ritual is a reminder of who’s in charge and their hierarchical value in that order, the mistresses engage in a savage competition to increase their value and its rewards, creating not sisterhood between them but ruthless gameplay. No player is better than Meishan, the former opera singer accustomed to artifice and controlling her performance. Songlian’s first night is interrupted by Meishan, who claims to be sick, drawing the Master’s attention away. Later, when Songlian catches Master Chen attempting to seduce Yan’er, she shows her anger and rebuffs him. He warns about her jealousy, “There are others desperate for a foot massage, you know.” And so, Master Chen spends the next night with Meishan. Songlian resists playing the game at first, but she soon realizes that the chosen mistress has control over her when Meishan’s menu selection does not align with her tastes. The sound of foot massage rattles on another mistress’ feet, too, creates a longing. The competition, she discovers, is constant and unrelenting. Even a friendly game of mahjong in Meishan’s room, which is decorated like a stage with theatrical masks to underscore the ever-present competitive performance in the compound, turns into a calculated distraction to keep the lanterns away from Songlian. Finally, Songlian begins to understand the extent of the other mistresses’ performance in the game. Talking about mahjong, but also about their competition for Master Chen, Meishan tells her, “I’ll let you win.” Songlian replies, “You don’t need to indulge me. We’ll see who wins and loses.”

Songlian faces competition from the other concubines and her maid, Yan’er, in a subplot that reveals the cruel limits of the hierarchical game. When she first arrives at the Chen compound, Songlian attempts to connect with Yan’er by squatting down to wash her hands, but Yan’er spurns her attempts to make a connection. The conflict escalates when Songlian finds Master Chen seducing Yan’er in her home, and Yan’er reveals her secret affections for him. Songlian responds by embracing their mistress-maid power roles and humiliates Yan’er—she inspects her hair for lice and orders Yan’er to wash her hair and clothes because they smell. Later, she suspects Yan’er stole her flute, a present from her father. When she raids Yan’er’s room to find it, she discovers that the maid has hung red lanterns in her room, a forbidden practice. “Mistresses are mistresses. Maids are maids,” Songlian declares. Later, in an act of revenge, she burns Yan’er’s lanterns in the square. Yan’er sits before the ashes over a cold winter night, mourning her hope until she’s hospitalized and eventually dies from exposure. While raiding Yan’er room, Songlian also finds a kind of voodoo doll stuck with pins. Someone has written Songlian’s name on the doll, but not the illiterate Yan’er. She soon discovers that the seemingly friendly Zhuoyun has orchestrated the curse. Songlian retaliates by intentionally cutting the second mistress’ ear while giving her a haircut, which only earns Master Chen’s sympathy for Zhuoyun. While each mistress does whatever she must to advance and win the game, Raise the Red Lantern shows how the game drives Songlian to cruelty and violence to get ahead. As one character describes it, their fate is to be “One of the master’s robes. He can wear it or take it off.” And yet, tragically, they all want the same thing. Zhang shows this with parallel shots in which Yan’er and Songlian hear the massage rattle at another house, and both close their eyes, dreaming of massaged feet, each aspiring to be upwardly mobile.

Raise the Red Lantern portrays a complex system of social and gender power structures. But to recognize how the film comments on China in 1991, some history is required to chart how cultural values shifted prior to the film’s historical setting until the time of its release. In the 1910s, the first signs of dissent against Confucianism appeared. Mao Zedong labeled Confucianism as exploitative, even though he used its hierarchical structure to establish himself as a new leader. Idealistically, Mao sought to undo the ancient dynastic system that had ruled China with oppressive poverty and social inequality. And while he sought to modernize Chinese culture in these ways, the outcome had many of the same societal problems as before. Zhang emphasizes these ironies and enduring conflicts in his film, using the historical period to disguise his critique and strengthen the parallels between the past and present. For instance, despite many gestures toward women’s liberation in the mid-twentieth century, Chinese culture remained dominated by a patriarchal hierarchy, evident in the film’s portrait of concubinage and echoed by how modern China regulates women’s bodies. Women no longer suffer the practice of foot binding and gained new rights during the century, including the ability to ask for a divorce from an unfaithful husband. But China’s regimented population planning measures and cultural inequalities for women reflect an enduring ideology that values male lives over female lives. Zhang’s critique does not go unnoticed, which lead to China briefly banning Raise the Red Lantern.

Raise the Red Lantern portrays a complex system of social and gender power structures. But to recognize how the film comments on China in 1991, some history is required to chart how cultural values shifted prior to the film’s historical setting until the time of its release. In the 1910s, the first signs of dissent against Confucianism appeared. Mao Zedong labeled Confucianism as exploitative, even though he used its hierarchical structure to establish himself as a new leader. Idealistically, Mao sought to undo the ancient dynastic system that had ruled China with oppressive poverty and social inequality. And while he sought to modernize Chinese culture in these ways, the outcome had many of the same societal problems as before. Zhang emphasizes these ironies and enduring conflicts in his film, using the historical period to disguise his critique and strengthen the parallels between the past and present. For instance, despite many gestures toward women’s liberation in the mid-twentieth century, Chinese culture remained dominated by a patriarchal hierarchy, evident in the film’s portrait of concubinage and echoed by how modern China regulates women’s bodies. Women no longer suffer the practice of foot binding and gained new rights during the century, including the ability to ask for a divorce from an unfaithful husband. But China’s regimented population planning measures and cultural inequalities for women reflect an enduring ideology that values male lives over female lives. Zhang’s critique does not go unnoticed, which lead to China briefly banning Raise the Red Lantern.

After the Qing dynasty’s fall, civil wars, Communist political campaigns, and the Japanese Occupation, Mao’s newly branded People’s Liberation Army developed its infrastructure with the help of Soviet Russia before setting off on its own Great Leap Forward—a movement started in 1957 that formed citizen communes to build up the country’s economic infrastructure. The Great Leap Forward ended after a series of natural disasters; floods, droughts, and crop failures tested the Communist government’s resolve, leaving the leadership divided. Liu Shaoqi took over for Mao during this time and achieved a level of economic stability in the 1960s, but not without allowing the Communist Party to become riddled with nepotism and elitism. As a result, Mao encouraged the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) led by Red Army volunteers to upend corrupt figures in Liu’s government. Revolutionaries destroyed symbols of privilege and arrested Liu. Despite his failing health, Mao, ever challenged by intellectuals, also incited the distrust and closure of academic and cultural institutions—among them, the China Film Archive, the country’s three film schools, and the circulation of almost all existing films. The so-called Gang of Four, a group of extremists deemed responsible for the revolution’s harshest policies, reinforced Maoist values by attacking the press, academics, and artists. They installed weekly meetings so people could learn how to think, and they sent dissenters to labor camps. But when Mao died in 1976 and named Hua Guofeng as his successor, Hua had the Gang of Four arrested. Although the harsh Cultural Revolution was over, Maoism still had several supporters, including Hua.

Enter Deng Xiaoping, a longtime revolutionary who nonetheless felt Maoism was too extreme. He pushed Hua aside and sought to eliminate corruption and support China’s failing economy. But Deng’s rule led to another series of political upheavals. Under Deng’s policy, dubbed the Opening of China, he supported consumerism, new technology, and private enterprise at home and abroad. His plans helped millions out of poverty, established a new healthcare system, and reinstated academic and artistic institutions. Yet, with the new economic resurgence, disparities between the rich and poor became increasingly problematic. Under the new ability to earn for oneself, ten percent of the population controlled the vast majority of land and wealth. Public workers and students called for equality, freedom of the press, and democracy to instill positive change. Citizens protested against Deng’s 1979 One Child Policy to control China’s rapidly growing population, along with the financial corruption within Deng’s party, rampant materialism, and housing shortages for underclasses. These factors reached a climax when thousands of demonstrators against corruption in the Communist Party met in Tiananmen Square, where the People’s Liberation Army dispersed them with tanks and guns, leaving thousands dead and more injured in a massacre that solidified the Chinese government’s authoritarian stance on the world stage.

These sweeping changes in Chinese culture throughout the twentieth century also significantly impacted China’s film industry. Although films released before the Communist takeover in 1949 were varied and often contained humanist themes, the Party closely monitored films as products of socialist reconstruction. Chinese filmmakers learned their craft and techniques from predominantly Russian instructors—students were sent to the Soviet Union to learn, or sometimes Soviet instructors came to the Beijing Film Academy to teach—resulting in predominantly social realist films. Moreover, the Party limited how many imports from the West, especially Hollywood films, could appear in Chinese theaters, which exhibited mostly Eastern European and Soviet pictures alongside Chinese cinema. As a result, the production of Chinese films declined dramatically, and after the Cultural Revolution in 1966, the state brought film production to a veritable standstill until 1976. Films were foremost propaganda concerned with controlling how Chinese people thought and how the country was viewed by international audiences. When they weren’t espousing the importance of a socialist family unit and self-sacrifice for the state, they were desperately trying to put forth what scholar Rey Chow called “a front” that China was modern, not a “backward” country of peasants. The films themselves could represent filmmakers’ views but only if those views aligned with the Party’s agenda.

These sweeping changes in Chinese culture throughout the twentieth century also significantly impacted China’s film industry. Although films released before the Communist takeover in 1949 were varied and often contained humanist themes, the Party closely monitored films as products of socialist reconstruction. Chinese filmmakers learned their craft and techniques from predominantly Russian instructors—students were sent to the Soviet Union to learn, or sometimes Soviet instructors came to the Beijing Film Academy to teach—resulting in predominantly social realist films. Moreover, the Party limited how many imports from the West, especially Hollywood films, could appear in Chinese theaters, which exhibited mostly Eastern European and Soviet pictures alongside Chinese cinema. As a result, the production of Chinese films declined dramatically, and after the Cultural Revolution in 1966, the state brought film production to a veritable standstill until 1976. Films were foremost propaganda concerned with controlling how Chinese people thought and how the country was viewed by international audiences. When they weren’t espousing the importance of a socialist family unit and self-sacrifice for the state, they were desperately trying to put forth what scholar Rey Chow called “a front” that China was modern, not a “backward” country of peasants. The films themselves could represent filmmakers’ views but only if those views aligned with the Party’s agenda.

Following Mao’s death, the Beijing Film Academy reopened and gave its first new round of graduates—including Zhang, Chen Kaige, and Tian Zhaungzhuang—an opportunity to examine social problems with a freedom new to Chinese filmmakers in what came to be known as the Fifth Generation. As for the previous four generations, these periods of Chinese filmmakers have been debated in scholarly circles, but Frances Gateward provides some generally accepted definitions: The First Generation spans from the silent era to the Japanese invasion of China in 1937; the Second Generation takes place during the war years, including the resistance against Japan and the Civil War; the Third Generation picks up after the Second World War, during the Communist takeover in 1949; the Fourth Generation was limited to the short period between Mao’s death and the reopening of the Beijing Film Academy. Although Zhang would become the most well-known of all Chinese filmmakers, Zhang Junzhao’s One and Eight (1983) and Chen’s Yellow Earth (1984) were the first two films of the Fifth Generation; they were also Zhang’s first two assignments during his early career as a cinematographer. Finally, the new filmmakers who emerged in China until the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 were followed by the Sixth Generation, which continues today.

These Fifth Generation filmmakers were encouraged by Deng’s government to critique the Cultural Revolution and explore the country’s history. Graduates learned how theme, color, objects, landscapes, and historical periods could strengthen the symbolic potential of their craft, moving film art away from the rigid realism of the Soviet style embraced in the past. By examining China’s history and questions of meaning and existence, the Fifth Generation disguised their message, which scholars Sheila Cornelius and Ian Haydn Smith characterize as “being caught between the tyranny of this feudal past and apparently spiritless commodity-orientated future.” To this extent, many Fifth Generation filmmakers used history as an allegory to raise questions about an establishment that had disrupted the lives of countless Chinese people, robbed them of an education, and eliminated their traditions. By simply looking at ideas that define a nation, the filmmakers could examine their contemporary nationhood and ideology. Cornelius and Smith describe their mission to “appease the Party, fool the censors, and negotiate the representation of reality as they saw and experienced it.” At once, these films captured the attention of Western viewers unfamiliar or previously uninterested in Chinese cinema, and they were recognized by the authoritarian government for their criticisms of the regime.

Zhang Yimou built a reputation in the global community with his stunning imagery and accessible narratives, but his films put him at odds with the Chinese censors. His directorial debut, Red Sorghum, earned several international awards, including the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. After making an uneven action follow-up called Codename: Cougar (1988), which he co-directed with Yang Fengliang, Zhang returned to the international stage with Ju Dou, which became the first-ever Chinese film to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. The attention on his work meant international investors wanted to collaborate with him. At the same time, his independence from China led to growing concerns about his output from censors. These factors meant Zhang would have the freedom to make films with a distinct voice and perspective; however, Ju Dou and other films would be received negatively by Chinese authorities, which prevented them from receiving distribution in mainland China. “Chinese films are not like Western films,” Zhang explained to Popular Culture in 1993. “They are neither a commodity nor a work of art—they belong in the realm of ‘ideology.’ That’s why they’re guarded so heavily—they know that film is a powerful medium for influencing thought.” To be sure, the censors recognized Zhang’s pattern of cultural criticism. It comes as no surprise, then, that Zhang made Raise the Red Lantern, a film about having to perform under the watchful eye of oppressive power, only to see it banned in China.

Zhang Yimou built a reputation in the global community with his stunning imagery and accessible narratives, but his films put him at odds with the Chinese censors. His directorial debut, Red Sorghum, earned several international awards, including the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. After making an uneven action follow-up called Codename: Cougar (1988), which he co-directed with Yang Fengliang, Zhang returned to the international stage with Ju Dou, which became the first-ever Chinese film to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. The attention on his work meant international investors wanted to collaborate with him. At the same time, his independence from China led to growing concerns about his output from censors. These factors meant Zhang would have the freedom to make films with a distinct voice and perspective; however, Ju Dou and other films would be received negatively by Chinese authorities, which prevented them from receiving distribution in mainland China. “Chinese films are not like Western films,” Zhang explained to Popular Culture in 1993. “They are neither a commodity nor a work of art—they belong in the realm of ‘ideology.’ That’s why they’re guarded so heavily—they know that film is a powerful medium for influencing thought.” To be sure, the censors recognized Zhang’s pattern of cultural criticism. It comes as no surprise, then, that Zhang made Raise the Red Lantern, a film about having to perform under the watchful eye of oppressive power, only to see it banned in China.

An acclaimed filmmaker in his own right, producer Hou Hsiao-Hsien played a vital role in Raise the Red Lantern’s production. Having enjoyed each other’s films, Hou and Zhang met in the late 1980s and began discussing a potential collaboration. Hou arranged for Taiwanese investor Chiu Fu-sheng to meet Zhang, who was promoting Ju Dou at Cannes in 1990. Together, the Taiwanese backers, working through a subsidiary company established in Hong Kong, gave Zhang the freedom to shoot what and how he wanted. Their deal had certain commercial benefits as well. In an interview with Robert Sklar for Cineaste in 1993, Zhang explained, “It was because of Taiwanese law that, to get a mainland Chinese film shown in Taiwan, it had to appear as if coming from a third party, from Hong Kong or Japan.” Because Raise the Red Lantern was backed by a Hong Kong company, it screened in Taiwan and earned sizable profits for its backers. The film also became a huge success abroad and remains among Zhang’s most celebrated and decorated works, having won the Silver Lion at the Venice International Film Festival and many other prestigious prizes. Even so, the film did not play well in China.

Most Chinese moviegoers were not drawn to Fifth Generation filmmakers, according to Cornelius and Smith; they preferred straightforward stories, from plain family dramas to action films from Hong Kong. Moreover, after the Tiananmen Square massacre, Chinese authorities began to tighten their grip on the film industry and viewership. They actively supported political films about the history of the Communist party and arranged for free tickets to screenings to encourage viewership. But the government’s crackdown on ideologically divergent films meant Zhang’s Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern could not be shown in Chinese theaters and were only allowed international distribution, according to Zhang, “to spread these ‘poisonous fumes’ abroad to foreigners—to weaken and harm them.” Scholar Mayfair Mei-Hui Yang clarified that the Bureau of Film in Beijing “was willing to release these films but could not get authorization from its superior administrative office, the Ministry of Radio, Film, and Television.” In a turn sometimes perceived as a bow to pressure resulting from Zhang’s growing international celebrity, the government reversed their ban in July 1992, after the head of the Propaganda Ministry, Li Ruihuan, personally viewed and approved of Zhang’s film. Li later declared that it was unreasonable to expect that “every single literary and artistic product must serve the function of political education”—a statement made in favor of Deng’s slow movement toward increased liberalization.

Although Raise the Red Lantern is not a product of pure “political education,” it does supply an unmistakable critique of Chinese culture through a historical and allegorical lens. But its sheer beauty and dramatic force may have distracted censors such as Li from its indictment of contemporary China. Indeed, the film’s detractors have accused Zhang of excessive visual splendor. “Can a film be too beautiful?” asked Anthony Lane in The New Yorker. Zhang’s signature as a filmmaker in his early films was to balance spectacular beauty and thematic weight. The director told interviewer Li Erwei that “good films should first be attractive” and that second they “should say something of substance.” Raise the Red Lantern goes beyond “attractive” and provides an entrenched visual schema, where form follows function to staggering heights. Although Zhang and Ni Zhen based the screenplay on a popular novella from the period, the director made distinct alterations to the text, such as adding the film’s lanterns “to give a concrete form to [the characters’] oppression.” The film is also pointedly claustrophobic, unfolding entirely within the compound aside from a single scene early on of Songlian on the road to her new life. Each visual choice works in unison with the film’s meaning. And yet, Zhang renders its tragedies beautiful, turning them into aesthetic wonders that overwhelm the viewer with a contrast of visual refinement and thematic gravity. This dynamic of surfaces and meaning underneath works to examine and understand the reality of how Chinese people live—supplying a correlation to the concubines in Master Chen’s compound who play his game and yet yearn to escape, and the Chinese people who maintain a façade under the thumb of the authoritarian government.

Although Raise the Red Lantern is not a product of pure “political education,” it does supply an unmistakable critique of Chinese culture through a historical and allegorical lens. But its sheer beauty and dramatic force may have distracted censors such as Li from its indictment of contemporary China. Indeed, the film’s detractors have accused Zhang of excessive visual splendor. “Can a film be too beautiful?” asked Anthony Lane in The New Yorker. Zhang’s signature as a filmmaker in his early films was to balance spectacular beauty and thematic weight. The director told interviewer Li Erwei that “good films should first be attractive” and that second they “should say something of substance.” Raise the Red Lantern goes beyond “attractive” and provides an entrenched visual schema, where form follows function to staggering heights. Although Zhang and Ni Zhen based the screenplay on a popular novella from the period, the director made distinct alterations to the text, such as adding the film’s lanterns “to give a concrete form to [the characters’] oppression.” The film is also pointedly claustrophobic, unfolding entirely within the compound aside from a single scene early on of Songlian on the road to her new life. Each visual choice works in unison with the film’s meaning. And yet, Zhang renders its tragedies beautiful, turning them into aesthetic wonders that overwhelm the viewer with a contrast of visual refinement and thematic gravity. This dynamic of surfaces and meaning underneath works to examine and understand the reality of how Chinese people live—supplying a correlation to the concubines in Master Chen’s compound who play his game and yet yearn to escape, and the Chinese people who maintain a façade under the thumb of the authoritarian government.

Zhang’s visual schema extends to his use of space and color. Raise the Red Lantern was shot on location inside a centuries-old walled gentry mansion in Shanxi Province. The director felt he had lucked out finding this spot, with its walled construction and design that “perfectly expresses the age-old obsession with strict order.” Inside the film’s systematized compound, red is everywhere. It’s an essential color in several Zhang films, from the titular red sorghum to the red silk in Ju Dou, from red lanterns to Gong Li’s red coat in The Story of Qiu Ju (1992), and her red dress in Shanghai Triad (1995). It is the most prominent color symbol in Chinese culture, appearing in the red sun, red flags, red envelopes, Red Guards, and red dragons. Zhang employs a traditional strategy for the color red, but he also uses it in rebellious terms. For instance, the red lanterns lit all day as symbols of longevity could represent the patriarch’s sexual control over his wives. They also suggest Songlian’s desire and victory in the competition among the other mistresses. The red “encourages unrestrained lust for life,” according to Zhang. It also represents female identity and danger in the same scene, when red menstrual blood appears on Songlian’s “white pants” or undergarments.

Zhang’s early work especially has been led by women, partly because each of his early films is based on a novel with a female protagonist, and his choice of material is based on the message he wants to convey. “What I want to express is the Chinese people’s oppression and confinement, which has been going on for thousands of years. Women express this more clearly on their bodies because they bear a heavier burden than men.” Raise the Red Lantern captures this idea as Songlian struggles at first with the rules of the game. She hatches a plan when Meishan warns, “Give him a son, or there will be hard times ahead.” This prompts Songlian to lie and claim she’s pregnant, which earns her the desired red lanterns, daily foot massages, and nightly visits from Master Chen. She hopes his regular visits will ensure an actual pregnancy. But after maintaining her deception for a short time, she is exposed when Yan’er, spitting on her mistress’ clothes as usual, notices a red spot on Songlian’s “white pants.” Yan’er notifies Zhuoyun, who calls for the doctor, and soon Songlian’s fraud is revealed. As punishment, Master Chen orders servants to cover the lanterns in her home with black cloth, the equivalent of a penalty box.

Zhang’s interest in a woman’s subjectivity is characteristic of how, for the first time in Chinese cinema, Fifth Generation filmmakers could portray women with an inner life of social ambitions and sexual desires, though they remained frustrated by their continued lack of agency. As noted earlier, the Cultural Revolution came with immense changes to women’s roles in Chinese culture. Under Confucianism, women were forced into marriage, brothels, and indentured servitude. After the revolution, they gained new rights concerning the freedom to marry or own property, while the male-dominated culture resisted reforms to the traditional expectations of women in Confucian value systems. By telling Raise the Red Lantern from Songlian’s perspective, Zhang not only shows how Confucianism devalues women but asks that his audience consider how women remain at odds with Chinese society. The film’s focus on Songlian’s desires gives her agency, even though she remains subjugated by Master Chen. Through a narrative perspective, Raise the Red Lantern condemns the patriarchy and, further, creates a parallel to the mistreatment of women by Zhang’s contemporary Communist Party.

Zhang’s interest in a woman’s subjectivity is characteristic of how, for the first time in Chinese cinema, Fifth Generation filmmakers could portray women with an inner life of social ambitions and sexual desires, though they remained frustrated by their continued lack of agency. As noted earlier, the Cultural Revolution came with immense changes to women’s roles in Chinese culture. Under Confucianism, women were forced into marriage, brothels, and indentured servitude. After the revolution, they gained new rights concerning the freedom to marry or own property, while the male-dominated culture resisted reforms to the traditional expectations of women in Confucian value systems. By telling Raise the Red Lantern from Songlian’s perspective, Zhang not only shows how Confucianism devalues women but asks that his audience consider how women remain at odds with Chinese society. The film’s focus on Songlian’s desires gives her agency, even though she remains subjugated by Master Chen. Through a narrative perspective, Raise the Red Lantern condemns the patriarchy and, further, creates a parallel to the mistreatment of women by Zhang’s contemporary Communist Party.

Zhang’s immersion into female subjectivity reaches beyond Songlian and extends to active denial of the film’s male characters. The director avoids showing Master Chen’s face in detail, and in most scenes, he appears either out of the frame, his face covered or turned away, or dwarfed in the frame in either medium or long shots. Similarly, Zhang avoids drawing attention to wealth outside of the hierarchical power dynamics that contain it. His camera, commanded by cinematographer Zhao Fei, never resorts to appreciating the material wealth of Master Chen’s compound. It feels more like an ornamented prison, contained within walls and aurally confined within Zhao Jiping’s sharp score of merciless theatrical cymbals and drums in a fast tempo. The exception is Feipu (Chu Xiao), Master Chen’s eldest son from his first wife, who appears to be about Songlian’s age and would probably be a more appropriate match. The film hints at an attraction between Songlian and Feipu, establishing the sole character who does not play the game and wants nothing from Songlian besides friendship. He plays the flute, just as Songlian and her father once did; thus, he represents a symbol from her past. Although Songlian believed Yan’er stole her father’s flute, Master Chen searched her belongings and, assuming some young male university student gifted her the instrument, burned it, in effect cutting her off from her former self. Only Feipu’s periodic presence stands as a reminder of who she once was.

If Raise the Red Lantern takes place in a veritable prison as suggested, it is a panopticon, where being watched changes one’s behavior. Except, in Songlian’s case, she cannot resist playing the game in which she has been placed. Larson describes this as “performance under coercion, the duplicity of display, and action under constraint.” Although Songllian plays, she does not fully realize the game’s deadly potential, signaled by the locked tower on a distant corner of the compound. The tower was used long ago to hang unfaithful wives, and Songlian dismisses it as a relic of a bygone era. However, she discovers how the past remains present in a tragic turn of plot. Early in the film, Songlian learns that Meishan is having an affair with Dr. Gao (Cui Zhihgang) when she spies them playing footsie under a mahjong table. After the incidents involving her false pregnancy and Yan’er’s death, Songlian falls into a depression. Then, in an act of self-pity on her twentieth birthday, she drinks too much and inadvertently reveals Meishan’s infidelity. Unfortunately, Zhuoyun hears and decides to act. A short while later, Meishan is dragged from her home and taken to the locked tower, where Master Chen’s servants use it once more to dispose of Meishan. Zhang uses the tower, though archaic and initially deemed a symbol of the past, to reveal his understanding of how the Chinese people live and its culture as unchangeable. “The Revolution has not really changed things,” Zhang once said. “It’s still an autocratic system, a feudal, patriarchal system. A few people still want to control everything and instill rigid order.”

The tragedy of Raise the Red Lantern is that Songlian remains locked inside of this order, aware of her commodification. With her half-year of university education, doubtlessly preceded by earlier education to prepare her for university, Songlian surely learned about equality and understands the degree to which she has been subjected and dehumanized. This is evidenced in a scene where Songlian and Meishan meet on a rooftop and discuss their situation. “They plot against me; I plot against them, back and forth. What’s the point?” Songlian ruminates. She is all too aware of the system, how its rituals reduce her to an animal or slave, to live within it and not go mad. She would rather die than continue playing the game. “Light the lanterns, blow out the lanterns, cover the lanterns. I really don’t care,” she says. “I just understand what people amount to in this household. They’re like dogs, cats, or rats. Whatever it is, they aren’t people. Standing here, I keep thinking, wouldn’t it be better to be hanged in that room?” But when faced with Meishan’s death, the horrific reality devastates her. “Murderers!” cries Songlian in a frantic outpouring. “You’re mad,” the servants say, attempting to gaslight her. “You didn’t see a thing.”

The tragedy of Raise the Red Lantern is that Songlian remains locked inside of this order, aware of her commodification. With her half-year of university education, doubtlessly preceded by earlier education to prepare her for university, Songlian surely learned about equality and understands the degree to which she has been subjected and dehumanized. This is evidenced in a scene where Songlian and Meishan meet on a rooftop and discuss their situation. “They plot against me; I plot against them, back and forth. What’s the point?” Songlian ruminates. She is all too aware of the system, how its rituals reduce her to an animal or slave, to live within it and not go mad. She would rather die than continue playing the game. “Light the lanterns, blow out the lanterns, cover the lanterns. I really don’t care,” she says. “I just understand what people amount to in this household. They’re like dogs, cats, or rats. Whatever it is, they aren’t people. Standing here, I keep thinking, wouldn’t it be better to be hanged in that room?” But when faced with Meishan’s death, the horrific reality devastates her. “Murderers!” cries Songlian in a frantic outpouring. “You’re mad,” the servants say, attempting to gaslight her. “You didn’t see a thing.”

Sometime later, in a final act of defiance, Songlian lights the lanterns in Meishan’s house and plays the phonograph with her voice singing opera loudly enough to echo throughout the compound, implanting the notion that they will be haunted by Meishan’s ghost. And while Songlian seems to have found a measure of victory with her subversion at that moment, the final scenes of Raise the Red Lantern reveal that a woman’s fate is utter annihilation by the patriarchal system. By the next summer, when a fifth mistress arrives to replace Meishan, the others explain to the newcomer that Songlian “was our fourth mistress. She has gone mad.” In Songlian’s final appearance, she wanders around her courtyard, aimless, dressed in the same pigtails and outfit she wore only the year before when she first arrived. She has restored herself to her former appearance and no longer participates in Chen family rituals, but she is alone and has lost her mind. Zhang details a system that suppresses intelligent, independent people and robs them of their individuality, paralleling contemporary China. Along with Raise the Red Lantern, most of Zhang’s early films focus on subjugated characters. He describes their message to Chinese people who “must always try to realize themselves in the face of oppression.” Perhaps this is why, after decades of increased censorship and ideological curbing of his artistic output by Chinese censors, Zhang has not left China for another country that might allow him to create more freely. He resolves to stay and has frequently said in interviews that he will never leave, regardless of his commercial success or the censorship of his films that continues today.

Zhang’s critique reaches into the past to lament how modernity cannot compete with the venerable and persisting cultural traditions. But his film is not without hope. When Songlian plays Meishan’s music on the phonograph, it’s a gesture that reflects Zhang’s faith that art—whether it be music, opera, or film—has the power to move people and enact change. Still, through its allegorical framework, Raise the Red Lantern assesses China’s past and present to intimate how little has progressed. Through Songlian, the intelligent young woman with boundless potential who yearns for authenticity yet succumbs to the Chen compound’s traditional and acidic view of existence, Zhang shows the degree to which performance remains inextricable from Chinese culture. The calculated game of cultural hierarchies and dream of upward mobility exists to create false hope for something better. Yet, in reality, women, emblematic of the culture at large in the film, remain unable to achieve true agency or a free society. The brilliance of Raise the Red Lantern, in tandem with its awe-inspiring beauty, carefully guarded performances, and masterful direction, rests in its themes of artifice and imprisonment, and the dangers of a culture that subsists in a perpetual performance driven by fear.

Bibliography:

Bernhardt, Kathryn. Women and Property in China, 960-1949. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Chow, Rey. Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. Columbia University Press, 1995.

Cornelius, Sheila, with Ian Haydn Smith. New Chinese Cinema: Challenging Representations. Wallflower Press, 2002.

Deppman, Hsiu-Chuang. “Body, Space, and Power: Reading the Cultural Images of Concubines in the Works of Su Tong and Zhang Yimou.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 15, no. 2, 2003, pp. 121–153. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41490906. Accessed 9 July 2021.

Gateward, Frances, editor. Zhang Yimou: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Larson, Wendy. Zhang Yimou: Globalization and the Subject of Culture. Cambria Press, 2017.

Lu, Sheldon Hsiao-peng. “National Cinema, Cultural Critique, Transnational Capital: The Films of Zhang Yimou.” Transnational Chinese Cinema: Identity, Nationhood, Gender. University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pp. 105-137.

Watson, Rubie S. and Patricia Buckley Ebrey, editors. Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press; first edition, 1991.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review