The Definitives

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

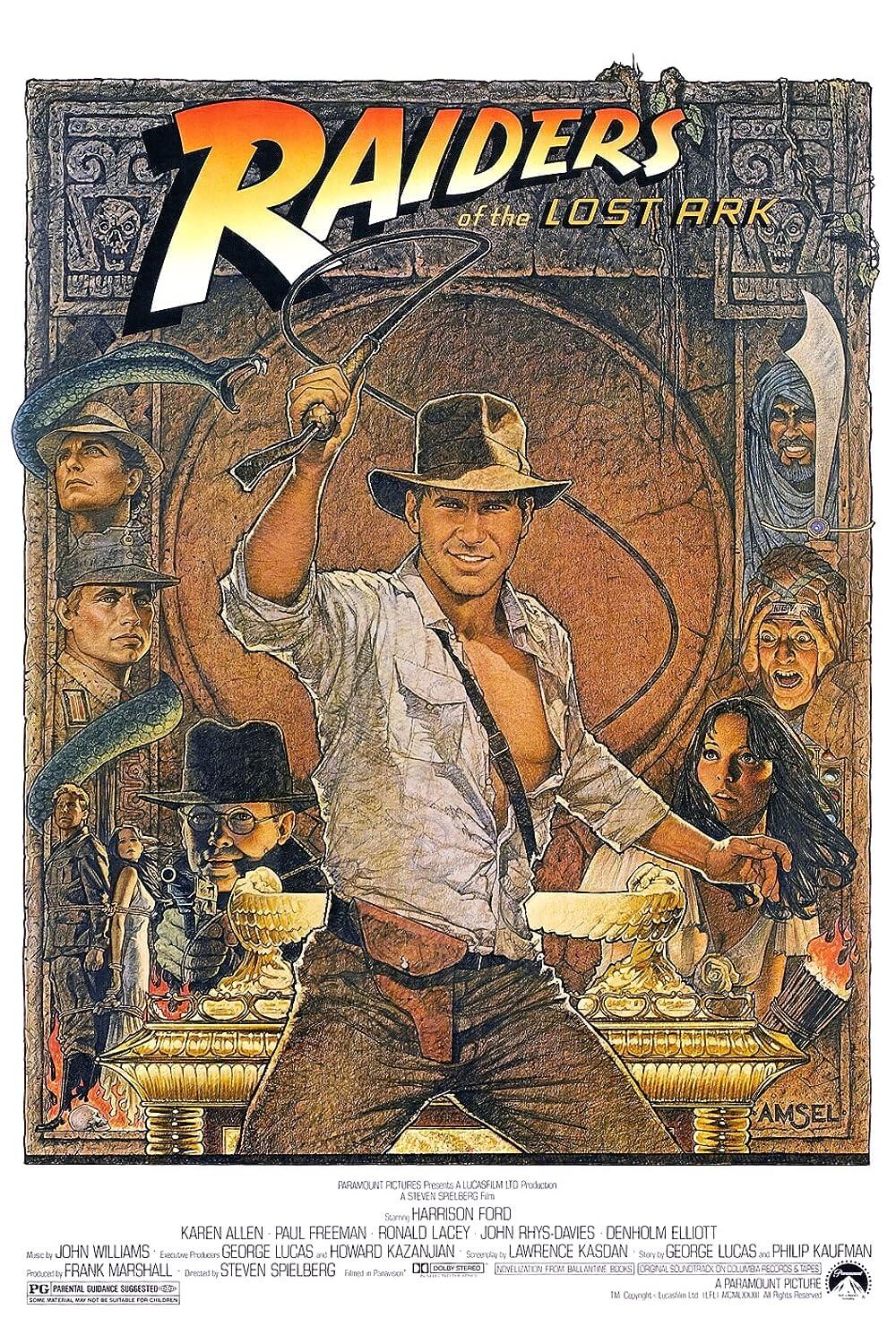

Every frame of Raiders of the Lost Ark contains an enduring iconography, not only because from scene to scene the picture surges with nonstop energy and craft, but because the production embraces a particular classicism balanced between nostalgia and sheer adventure. An undeniably familiar, reminiscent quality flows from director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas’ brilliantly spun yarn, from their use of historical and religious imagery to their deliberate evocation of Saturday matinee serials, all of which form an instant bond between the audience, film, and memory. This bond is not limited to the past, however. Raiders of the Lost Ark reconnects the viewer with various histories; it also transcended those elements in 1981 by creating a bold new standard for adventure and blockbuster filmmaking. Countless imitators since the film’s release have made it an influential landmark. It is the ultimate escapist ride in which every subsequent foray into the genre attempts and ultimately fails to live up to.

In the preamble alone, Harrison Ford’s archeologist-adventurer, Indiana Jones, thwarts a double-cross, brushes away crawling spiders, dodges deadly traps, finds an ancient treasure, outruns a gigantic tumbling boulder, and narrowly escapes capture onto a plane. Watching the film is an experience entrenched in youthful escape. The whole viewing experience feels as though we’re seeing what happened when a young boy went out into the back yard to play adventure hero with his toys, except the boy has an $18 million budget backing his imagination, not to mention locations in Hawaii, La Rochelle, Tunisia, and England’s Elstree Studios where he can play. Steven Spielberg is the boy, his action figures are actors, and his playsets are the stuff of Hollywood movie magic. Indeed, Spielberg’s vision is rendered with a childlike intimacy and enthusiasm, his story rooted in the concerns of a rebellious teen, and his production executed with the precision of a master. From this, he shapes unsurpassed escapist cohesion.

The first inkling of Indiana Jones was conceived back in 1973 by George Lucas, who, following a similar design for Star Wars, sought to revive the conceptual makeup of serials from The Golden Age of Hollywood both in story and execution. He pitched “The Adventures of Indiana Smith” to Steven Spielberg in 1977 while the two were on holiday together in the Hawaiian Islands, both recovering after their strenuous productions of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Lucas envisioned a James Bond thread based in the Saturday serial style and set around a soldier of fortune archeologist; though, Lucas’ model would later be guided away from his original dark playboy hero concept into the duality of professor-adventurer. Retooling the name from Smith to Jones and perfecting character attributes with screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan (Body Heat, The Big Chill), Lucas and Spielberg brainstormed what would later become key sequences in the film and its 1984 prequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Kasdan constructed the screenplay from their talks and refined the jumble of ideas coming from his producer and director into a wispily plotted adventure tale.

The first inkling of Indiana Jones was conceived back in 1973 by George Lucas, who, following a similar design for Star Wars, sought to revive the conceptual makeup of serials from The Golden Age of Hollywood both in story and execution. He pitched “The Adventures of Indiana Smith” to Steven Spielberg in 1977 while the two were on holiday together in the Hawaiian Islands, both recovering after their strenuous productions of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Lucas envisioned a James Bond thread based in the Saturday serial style and set around a soldier of fortune archeologist; though, Lucas’ model would later be guided away from his original dark playboy hero concept into the duality of professor-adventurer. Retooling the name from Smith to Jones and perfecting character attributes with screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan (Body Heat, The Big Chill), Lucas and Spielberg brainstormed what would later become key sequences in the film and its 1984 prequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Kasdan constructed the screenplay from their talks and refined the jumble of ideas coming from his producer and director into a wispily plotted adventure tale.

Never deriving from a direct source, the film’s emulation of cliffhanger-laden serials from the 1930s-1950s—those featuring heroes like Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, The Phantom, The Perils of Pauline, and Tarzan, among others—is flawless. Each Saturday, a series would return to theaters, running through its succession chapter after chapter, week after week, always seemingly ending with the penultimate finale, the audience rapt as they wondered if this the week their hero would make it out alive. A serial adventurer confronts insurmountable dangers bringing him inches from death, leaving him to stop the Bad Guy, save The Girl, plant a smooch on her lips, and locate the treasure that splashes a golden light onto his face. The story is the same every time but with a detail or two switched around for effect, embracing enough all-out excitement to keep audiences returning to finish out the fifteen to twenty consecutive episodes. Raiders of the Lost Ark has the same effect, simply without a week between the serial’s deathly setup and learning the outcome. Instead, the film’s action sequences are strung together like so many pearls.

How draining it is to endure Indy barely surviving an onslaught of neverending dangers! Those with breathing troubles should avoid viewings, as we constantly gasp and hold our breath with barely a moment allowed to catch up. Setup as a progression of cliffhangers like so many serials, the plot moves from place to place, tracking with lines on a map each stop from Peru to Nepal to Egypt and so on, never allowing our attention spans to relax and keeping us perpetually thrilled. We watch Indy dodge poison-tipped darts, survive snake-filled tombs, outsmart nefarious Nazis, and in the end, of course, save the day (or at least recover the artifact his government commissioned him to obtain). Set in 1936, the picture tails us behind Harrison Ford’s embodiment of part-time college professor and full-time history-defending Indiana Jones, whose bored students seem oblivious to their instructor’s off-the-clock exploits but not-so unaware of his sex appeal. He’s assisted in the scholarly by Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliot), with resources by Egyptian excavator Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), and in the adventure of romance by long lost love interest Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). Indy’s need for others plays a great role in forming Ford’s intensely human, subtly flawed, but heroic character.

Famously, scheduling and contract conflicts with Magnum P.I. barred Tom Selleck from accepting the Indiana Jones role, leaving it open for Ford’s most memorable and beloved performance. Lucas popularized Ford as Han Solo in his Kurosawa-inspired space opera, making the otherwise unknown actor a cowboy of the stars. And despite the popularity Ford’s Solo would receive between A New Hope and Return of the Jedi, he was not yet a screen idol when cast in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Often noted for his dry humor, Ford’s naturalism is his greatest appeal and the lasting characteristic of his performance. He carries out the bulk of his own stunts, so when Indiana Jones is dragged behind a Nazi truck, we see Ford’s face and not some stuntman’s. He is perhaps the most easily identifiable physical presence in Hollywood, marked by his signature haphazard run and half-cocked smile. The actor’s wobbliness emphasizes Jones’ peak appeal: his vulnerability, his humanness. Indy takes blow upon blow, leaving him bruised and battered, and when the adventure is all over, he takes a nap, reclined with his distinctive fedora pulled down over his eyes.

Famously, scheduling and contract conflicts with Magnum P.I. barred Tom Selleck from accepting the Indiana Jones role, leaving it open for Ford’s most memorable and beloved performance. Lucas popularized Ford as Han Solo in his Kurosawa-inspired space opera, making the otherwise unknown actor a cowboy of the stars. And despite the popularity Ford’s Solo would receive between A New Hope and Return of the Jedi, he was not yet a screen idol when cast in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Often noted for his dry humor, Ford’s naturalism is his greatest appeal and the lasting characteristic of his performance. He carries out the bulk of his own stunts, so when Indiana Jones is dragged behind a Nazi truck, we see Ford’s face and not some stuntman’s. He is perhaps the most easily identifiable physical presence in Hollywood, marked by his signature haphazard run and half-cocked smile. The actor’s wobbliness emphasizes Jones’ peak appeal: his vulnerability, his humanness. Indy takes blow upon blow, leaving him bruised and battered, and when the adventure is all over, he takes a nap, reclined with his distinctive fedora pulled down over his eyes.

Legendary when he first appears onscreen, Indiana Jones has a reputation before his adventure begins: he is a known “obtainer of rare antiquities.” The government agents asking him to acquire The Ark of the Covenant from a band of Nazis already know his standing and reference his renowned fantastical exploits. Who else but the famous Dr. Jones would they ever entrust with such a task? His first filmic story feels as though it should be his fifth, as he needs no origin tale to be understood; rather, his onscreen persona is so singular and immediate that within the first fifteen minutes, we have all requisite information we need: Always covered in dust from whatever cavern or tomb he exhumes, Indiana Jones is a pseudo-cowboy exploring the world’s historical frontiers, even riding the occasional horse and exemplifying cowboy iconography. He is a hero in the most straightforward way. He penetrates the vast unknowns of history looking for fact (not truth, he reminds us in The Last Crusade, “If it’s truth you’re looking for, Dr. Tyree’s philosophy class is right down the hall.”), though he often finds himself directly engrossed in cultural mysticisms, the upshots make him spiritual, not religious, but certainly a historical romantic.

Every adventure story, Indiana Jones’ more than most, requires a MacGuffin—the device around which the film’s events revolve. Otherwise, what is our adventure-seeker seeking and why? Early concept talks between Lucas and Phillip Kaufman pinpointed the Ark of the Covenant, and Kaufman received story credit due to his contribution. A MacGuffin’s specificity can and often is inconsequential: a Maltese Falcon, Sankara Stones, Captain Kidd’s lost treasure, the Holy Grail, Cortés’ gold, Crystal Skulls, or the unearthed tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi. The journey’s the thing, as they say. These details are often obsolete next to the respective film’s momentum, but not in Raiders of the Lost Ark; this particular MacGuffin is not so impersonal as to be dismissed as a mere storytelling contrivance to propel the plot. A piece of Hebrew lore, the Ark was built under God’s instruction (complete with mathematical assembly instructions) to contain the tablets with the Ten Commandments inscribed by Moses, lending Spielberg’s picture a religious background which audiences instantly recognize the importance and wonderment thereof. More importantly, it’s doubtful anything so engrained into Hebrew legend could be insignificant to the same Jewish filmmaker who made Schindler’s List.

Taking another cue from Saturday serials, Raiders of the Lost Ark adopts Nazis as its villains. But more than just Nazis, these are quintessentially evil Nazis, and in opposition to them, Indiana Jones stands as quintessentially good. Indeed, Spielberg takes joyous aim against Nazis and presents them as dehumanized, exceptionally malevolent, and single-minded in their utter evil. They are the antithesis to Jones and the unhallowed exploiters of all that is divine, signified by the Ark. When the Nazis’ swastika is imprinted upon the wooden crate containing the relic, we hear burning godly radiation singe away their stamp. Historically used by Abrahamic, Buddhist, Christian, and Hindu religions, and others, the swastika dates back to the Neolithic Period, formerly signifying universality and good luck. But never mind its origins or positive uses. The Nazis’ particular brand of malevolence and prominent implementation of the image wipes away any application before or since their (relatively) brief reign of terror, mutating the symbol into a universally known signature of evil, which Spielberg emphasizes to powerful thematic ends by suggesting Nazi imagery alone is unholy.

Taking another cue from Saturday serials, Raiders of the Lost Ark adopts Nazis as its villains. But more than just Nazis, these are quintessentially evil Nazis, and in opposition to them, Indiana Jones stands as quintessentially good. Indeed, Spielberg takes joyous aim against Nazis and presents them as dehumanized, exceptionally malevolent, and single-minded in their utter evil. They are the antithesis to Jones and the unhallowed exploiters of all that is divine, signified by the Ark. When the Nazis’ swastika is imprinted upon the wooden crate containing the relic, we hear burning godly radiation singe away their stamp. Historically used by Abrahamic, Buddhist, Christian, and Hindu religions, and others, the swastika dates back to the Neolithic Period, formerly signifying universality and good luck. But never mind its origins or positive uses. The Nazis’ particular brand of malevolence and prominent implementation of the image wipes away any application before or since their (relatively) brief reign of terror, mutating the symbol into a universally known signature of evil, which Spielberg emphasizes to powerful thematic ends by suggesting Nazi imagery alone is unholy.

Consider the possibility of a less absolute villain. If it weren’t for the Nazis, Indiana Jones would be just another soldier of fortune competing against someone not unlike himself, rather than a do-gooder of superhero proportions. But more than that, Spielberg’s passion in the project is felt so potently because the story, even on its pure escapist level, weighs on the filmmaker’s Jewish heritage. After all, the Nazis’ ultimate “solution” of wiping the Jews from the planet was Hitler’s sadistic design, while the film remarks that Hitler himself is a “nut” for Ark lore. At stake then is not only the fate of an archeological landmark but the entire Jewish people, which for Spielberg must have sounded a personal involvement in the story, even if his treatment of this theme avoids dwelling on the story’s weightier implications. Unlike Jaws, where bringing mass entertainment to the screen was a mere job handed down to him, Raiders of the Lost Ark feels like a kind of lightweight passion project for the director. He must take some kind of adolescent delight from instilling Nazi iconography as the language of sin, and moreover, representing the Nazis as cartoonishly evil adventure villains to further their status as the ultimate, unquestioned movie bad guys—so evil their faces melt from the wrath of God in the presence of holy spirits. Even the Nazis’ henchman, the Vichy slime Belloq (Paul Freeman), is unwaveringly venal.

Beyond recalling religious and historical iconography, Spielberg delves into motion picture iconography as well. In keeping with the enduring classicism of the entire picture, Spielberg’s approach remains rooted deeply in Golden Age cinema traditions. The direction and mannerisms of certain actors springs from early cinema action yarns. Spielberg’s visual flourishes recall those of legend Michael Curtiz on films like The Adventures of Robin Hood. He even occasionally throws some of his action up on the wall in silhouetted shadow—such as in Marion’s bar scenes or Indy inside the Ark’s tomb—a staple of Curtiz’s oeuvre. Meanwhile, Ford carries the undeniable charisma of Humphrey Bogart and the brash physicality and humor of Errol Flynn, meeting somewhere in the middle with a charming impetuousness. As Indiana’s love interest, Allen is never reduced to merely a damsel in distress; she partakes in drinking contests and throws hard punches but never forgets her femininity, recalling Barbara Stanwyck’s greatest roles. And lest we forget the nefarious Major Toht (Ronald Lacey), the spitting image of Peter Lorre; he laughs with a sinister, nasal hee–hee we love to hate.

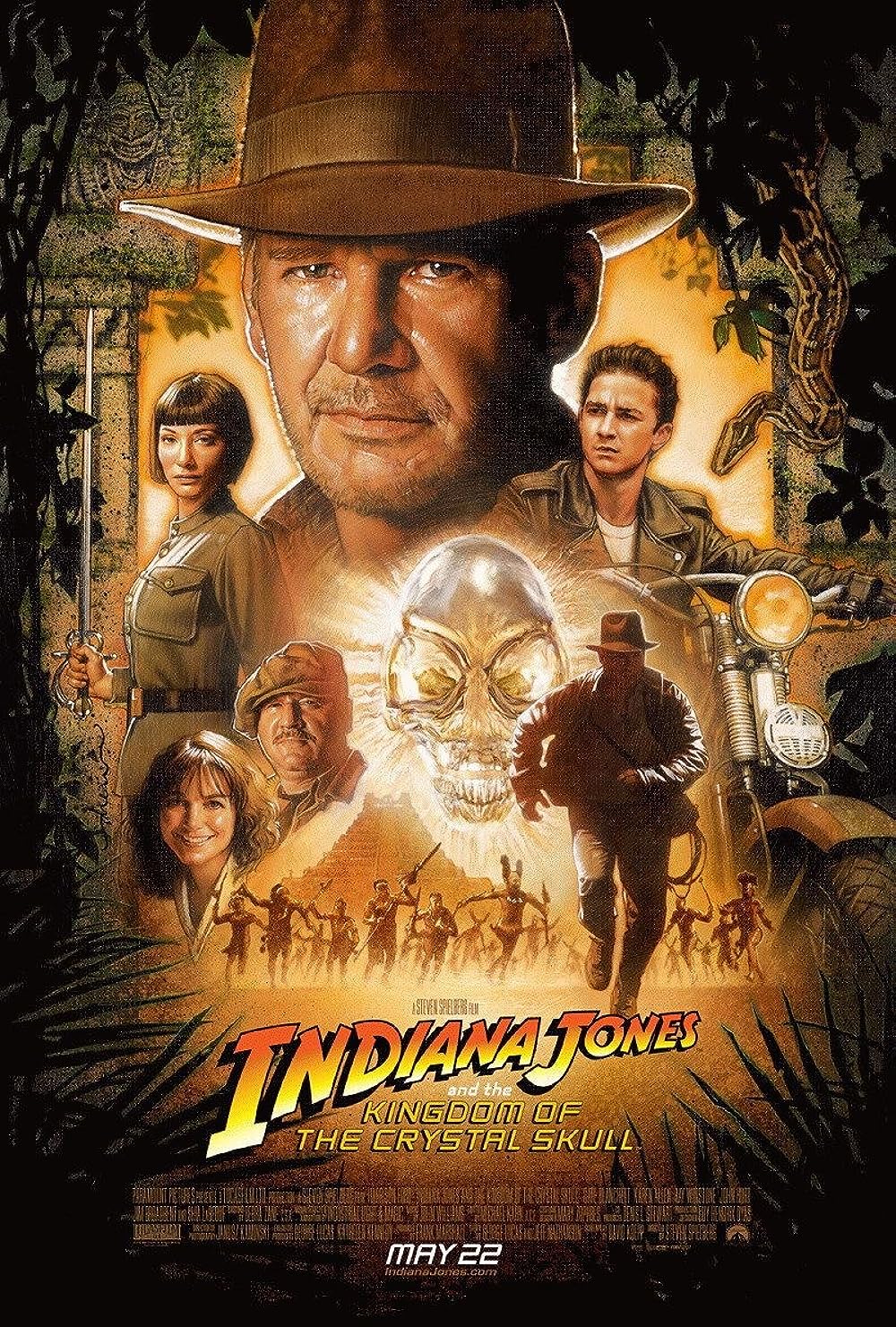

As suggested, the film’s instantaneous classicism is not only rooted in the past but as a result of the iconography that Spielberg himself creates, or in some cases recreates from scene to scene. Take his reclamation of the Paramount Pictures mountain logo. Each Indiana Jones film is preceded by this studio logo, an image used in some form or another for the company’s more than a hundred years of making motion pictures. An illustration familiar to moviegoers, the logo fades into a similar mountaintop landscape in Raiders of the Lost Ark’s Peruvian jungle scenes, filmed on location in Hawaii (whose peaks were scouted for this very reason). This trend continues in the sequels with the embossed Shanghai gong in Temple of Doom, Utah’s Arches National Park scenes in The Last Crusade, and, quite humorously, the groundhog mound in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. The effect connects the viewer with a history of filmmaking as amusement, escape, entertainment, and fun, suggesting Spielberg seeks to appease imaginations and blockbuster appetites in the same sweep instead of generating something more severe to be contemplated and analyzed.

As suggested, the film’s instantaneous classicism is not only rooted in the past but as a result of the iconography that Spielberg himself creates, or in some cases recreates from scene to scene. Take his reclamation of the Paramount Pictures mountain logo. Each Indiana Jones film is preceded by this studio logo, an image used in some form or another for the company’s more than a hundred years of making motion pictures. An illustration familiar to moviegoers, the logo fades into a similar mountaintop landscape in Raiders of the Lost Ark’s Peruvian jungle scenes, filmed on location in Hawaii (whose peaks were scouted for this very reason). This trend continues in the sequels with the embossed Shanghai gong in Temple of Doom, Utah’s Arches National Park scenes in The Last Crusade, and, quite humorously, the groundhog mound in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. The effect connects the viewer with a history of filmmaking as amusement, escape, entertainment, and fun, suggesting Spielberg seeks to appease imaginations and blockbuster appetites in the same sweep instead of generating something more severe to be contemplated and analyzed.

Raiders of the Lost Ark explores and re-consecrates an adventure style unused and forgotten for decades, but also fashions its own milestone through awe-inspiring, splendidly tangible effects setups, unmatched in their natural grandeur and scope even with today’s computer technology. Some filmmakers rely on advanced CGI to easily render special FX, including Spielberg in many of his later science-fiction undertakings. Here, Spielberg remains grounded by the film’s tactile reality in an ode to the film’s Saturday serial origins. Shot fast and with few takes, the naturalistic execution of the production alone, accomplished by designer Norman Reynolds, feels familiar, playful, gritty, and genuine. The more elaborate effects were conceived in large part by Lucas’ genius company Industrial Light & Magic. There’s nothing computer-generated about the obvious model planes, nor anything artificial about Indy going face-to-face with a cobra, Marion hanging from a statue’s jaw in an evening dress, or Indy’s fisticuffs with a brutish Nazi ending in a propeller disaster. In-camera effects, matte paintings, and makeup do the rest. And yet, with such epic-sized physical imagery, subtler details like the interlude map trailing Indy’s course from country to country remain equally characteristic and illustrative of Spielberg’s throwback classicism.

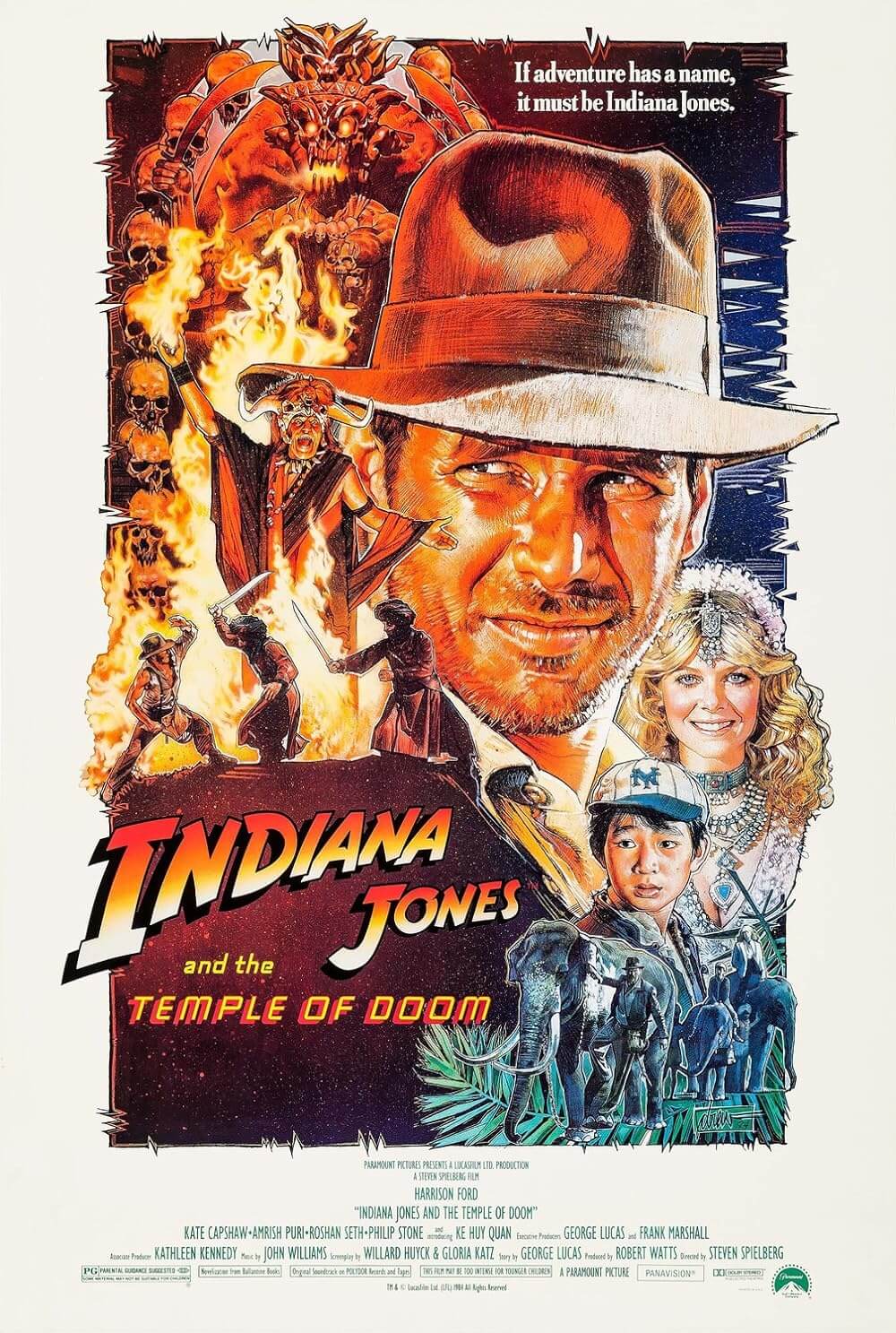

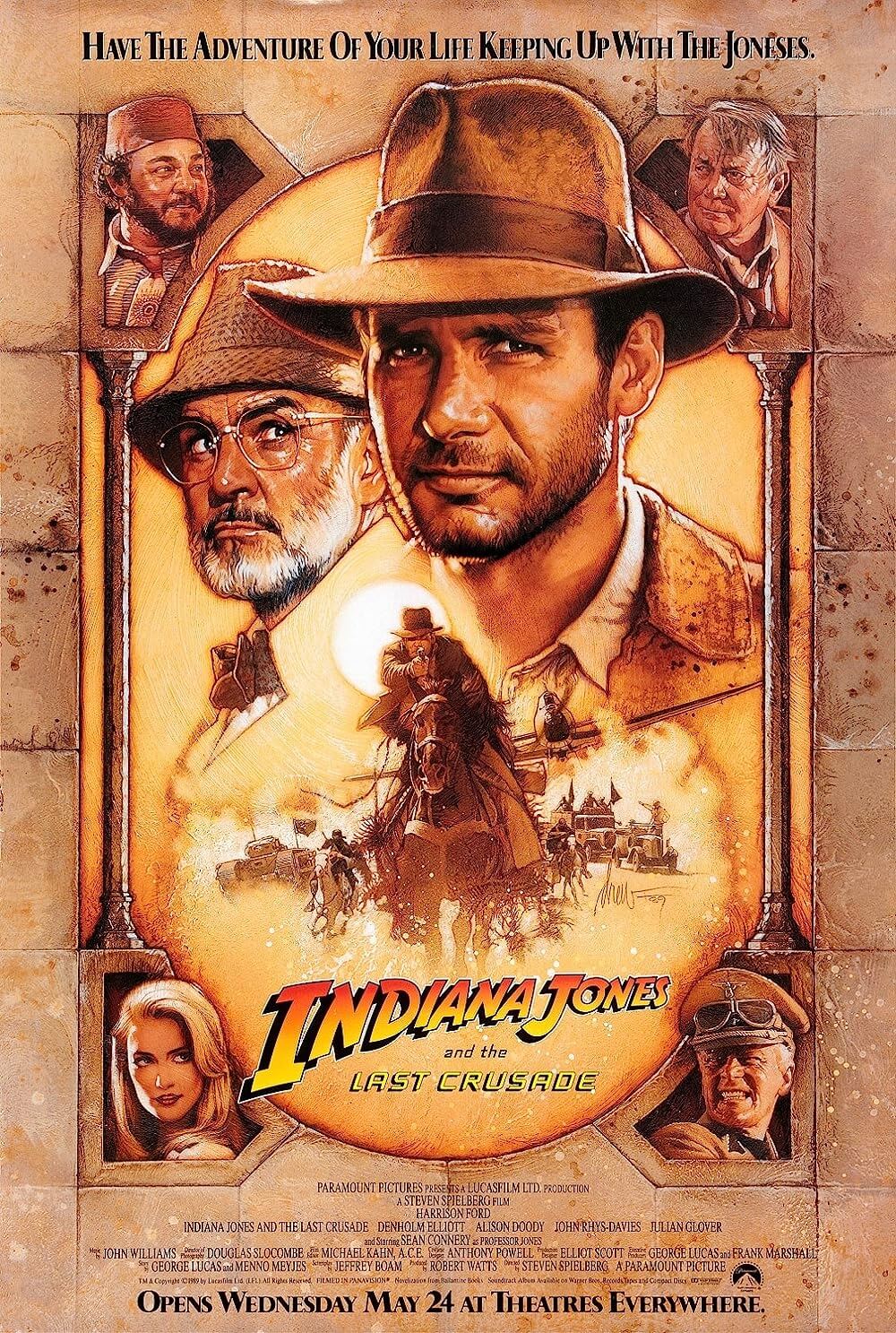

Upon its release, the picture’s sources became less important than the film itself, which attained rapid pop-culture phenomenon status, earning over $200 million in domestic box-office receipts, enthusiastic reviews, and adoration from moviegoers. Raiders of the Lost Ark would be nominated for nine Academy Awards in 1982, winning four for Best Art Direction, Best Film Editing, Best Sound, Best Visual Effects, and a fifth Special Achievement Academy Award to Ben Burtt for his unique Sound Effects Editing. Over the years, several sequels, videogames, and a spinoff TV show would follow. In adapting the past, Spielberg and company had created a brand all its own, a trademark so singular even the silhouette of Indiana Jones is recognizable. From John Williams’ score to the posters painted by Drew Struzan, every facet of the film would become and still is iconic. And though some critics, most notably Pauline Kael, would dismiss the production as a product of a New Hollywood “marketing department,” the film has outlived such critiques because, as much as it is a successful blockbuster and another landmark for Spielberg, it is great filmmaking.

The film’s legacy has an incandescence gleaming from the entire production, radiant with the gilded character of Golden Age cinema and its inescapable link to the historical imagery therein. Shining even more is Spielberg’s distinct touch, a splendorous glow of icon renovation and discovery, his way of fathering images that somehow burn into our collective memory and remain there for all time. How impossible it is to feel anything but wonderment about this film, like Indiana Jones himself standing before his shimmering prize, the rays of this treasure illuminating his face. As moviegoers and cinephiles, we often dodge the traps of Hollywood’s disappointments and leap over its treacherous half-hearted failures. But rarely do we find a motion picture like this at the end of our journey, burnishing as it does under a light from above, just waiting for us to take it. There it sits, a perfect and immaculate treasure combining artistry and entertainment in a way only true masters can achieve. Upon finding Raiders of the Lost Ark on its dais, before we escape with our prize, we must take a moment to stand back in awe and admiration, our faces enlightened to a kind of filmmaking decades old in 1981 and all but lost today.

Bibliography:

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). London. Faber and Faber, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review