The Definitives

Raging Bull (1980)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

(This essay was originally published on June 29, 2009. It has been edited and expanded.)

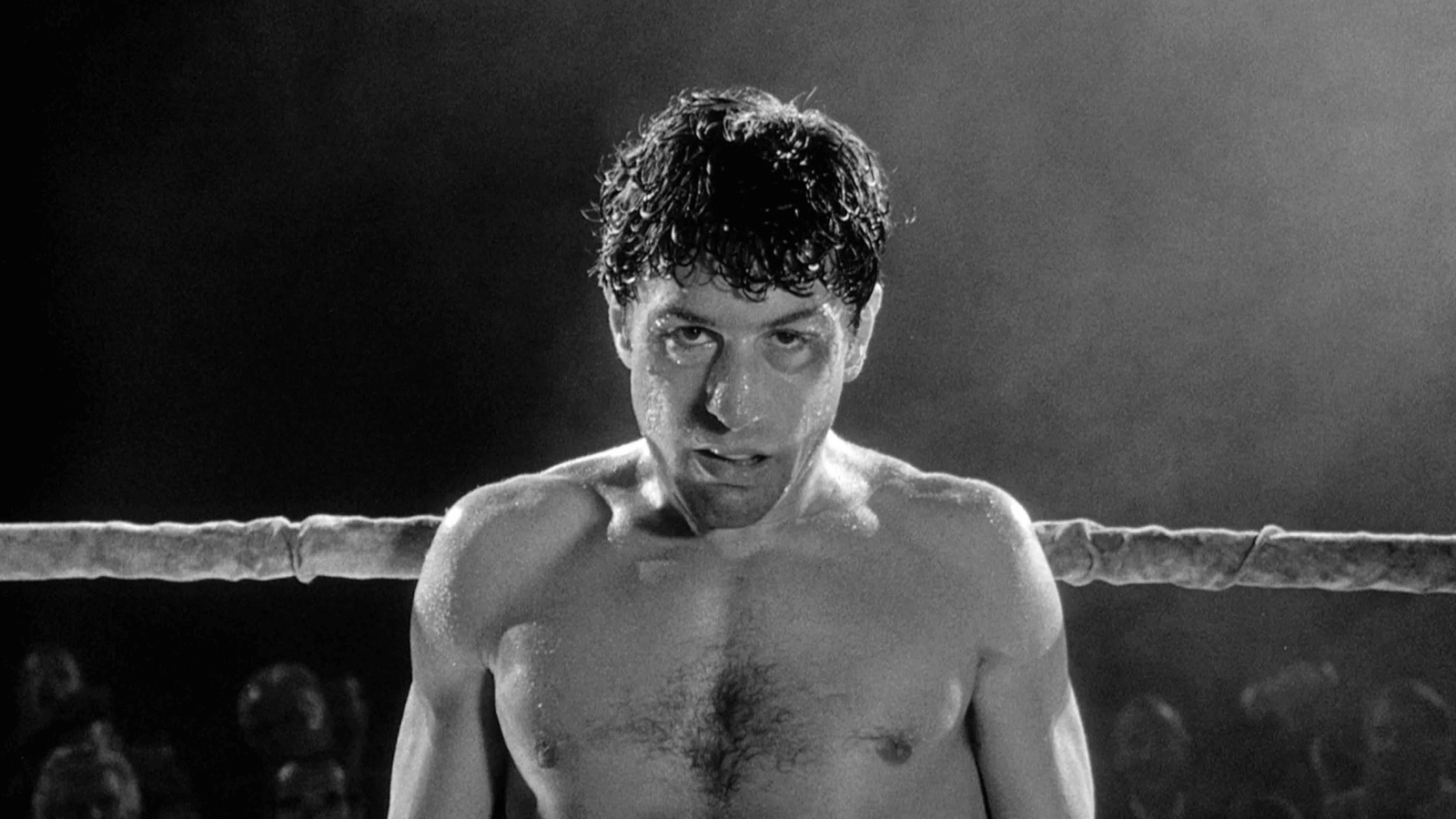

Martin Scorsese composes an artful examination of a brutal subject in Raging Bull. Middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta, driven by aggression, jealousy, sexual repression, and self-hatred, becomes a text for Scorsese to critique masculinity and masculine violence. The character comes to life through Robert De Niro’s greatest performance, a legendary bodily transformation only matched by the psychological complexity on display. A passion project for the actor, De Niro’s LaMotta weighs his masculine instincts against his Christian guilt and finds the only way to release the inevitable conflict is through unrelenting violence, in or outside the ring. The film also became a personal statement from the filmmaker. In Scorsese’s portrait of LaMotta’s externalization of his inner conflict, the director captures recurrent themes that appear throughout his body of work in their most crystallized form. Although LaMotta could not be called redeemed by the final frames, the Biblical quote at the end credits, “Once I was blind, and now I see,” represents the filmmaker’s redemption after a severe personal and professional downswing. Given this, Raging Bull has often been hailed as Scorsese’s most personal work that encapsulates his career-long critique of unchecked masculinity, seen elsewhere in his many films about gangsters or corrupt systems of male power.

Robert De Niro first gave the director a copy of Jake LaMotta’s semi-autobiographical book, written by LaMotta along with Pete Savage and Joseph Carter, while Scorsese was filming Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in 1974. De Niro had discovered it the year before while shooting The Godfather Part II (1974) in Sicily. Although the director was drawn to the depiction of New York’s Italian-American community around the same period he grew up, Scorsese had no interest in boxing and continued to postpone the adaptation for years, preferring projects that he understood more innately. The director later admitted he could not figure out the Jake LaMotta character when De Niro first approached him to direct Raging Bull. Not impressed with the book’s desire to explain away each and every bit of LaMotta’s irrational and self-destructive behavior through contrived motivations, Scorsese eventually found his personal bond to the material: In 1978, he nearly died at age 35. A combination of his hard lifestyle, cocaine addiction, and asthma left Scorsese hospitalized in the wake of two failed pictures, New York, New York (1977) and The Last Waltz (1978). Over 10 days, Scorsese prayed “just to get through those 10 days and nights.” If he were saved, he felt there must be “some reason. And even if it wasn’t for a reason, I had to make good use of it.”

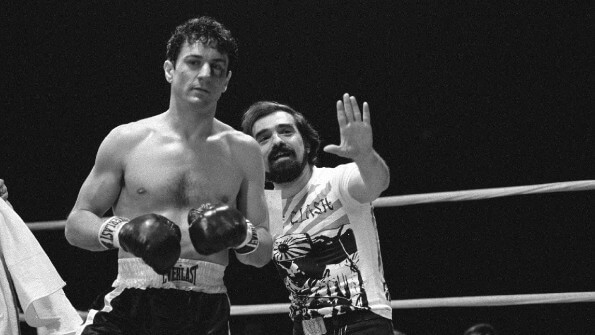

During his time in the hospital, Scorsese was visited by De Niro, who petitioned once more for the director to helm this passion project. Only then, in his rock-bottom state, could Scorsese recognize something about himself in LaMotta—a state of distinctly masculine denial about his behavior that LaMotta demonstrated as an untamable destructive force, edging blindly toward his own ruin. Scorsese credits the episode with saving his life. As for the script, Mardik Martin and Paul Schrader had already completed drafts between 1976 and 1978, but Scorsese and De Niro would spend two-and-a-half weeks in San Martin in the Caribbean revising, condensing, and rewriting an entirely new screenplay. Scorsese watched boxing fights at Madison Square Garden to learn the sport. De Niro’s training included a rigorous gym regimen, where, overseen by LaMotta, he learned the boxer’s distinct style. De Niro put on 20 pounds of muscle and became so skilled that he participated in three anonymous professional bouts, and he won two of them. The director and actor’s close collaboration throughout the filming of Raging Bull found them debating and questioning every creative decision, which defies the usual understanding of the director or screenwriter as the film’s author, especially in Scorsese’s case. With Raging Bull, the strength of De Niro’s performance and his close working relationship with Scorsese present an alternative authorship model, while the director’s personal understanding of LaMotta heightened the filmmaking.

During his time in the hospital, Scorsese was visited by De Niro, who petitioned once more for the director to helm this passion project. Only then, in his rock-bottom state, could Scorsese recognize something about himself in LaMotta—a state of distinctly masculine denial about his behavior that LaMotta demonstrated as an untamable destructive force, edging blindly toward his own ruin. Scorsese credits the episode with saving his life. As for the script, Mardik Martin and Paul Schrader had already completed drafts between 1976 and 1978, but Scorsese and De Niro would spend two-and-a-half weeks in San Martin in the Caribbean revising, condensing, and rewriting an entirely new screenplay. Scorsese watched boxing fights at Madison Square Garden to learn the sport. De Niro’s training included a rigorous gym regimen, where, overseen by LaMotta, he learned the boxer’s distinct style. De Niro put on 20 pounds of muscle and became so skilled that he participated in three anonymous professional bouts, and he won two of them. The director and actor’s close collaboration throughout the filming of Raging Bull found them debating and questioning every creative decision, which defies the usual understanding of the director or screenwriter as the film’s author, especially in Scorsese’s case. With Raging Bull, the strength of De Niro’s performance and his close working relationship with Scorsese present an alternative authorship model, while the director’s personal understanding of LaMotta heightened the filmmaking.

The film takes place in the 1940s and the ensuing decades, in Little Italy, the same neighborhood where Scorsese spent his childhood. From the outset, Jake LaMotta suffers from an inferiority complex and fights with unwavering desperation to prove himself. A ring announcer calls him, “A man who doesn’t know how to back up.” But no matter what he does, his potential only reaches second place, meaning the middleweight ring. His opponents fear him to be sure, but he will never be a heavyweight. He tells his brother Joey (Joe Pesci) that his “little girl’s hands” will prevent him from entering The Big Leagues. He asks his brother to punch him in the face as hard as he can, slapping and insisting until Joey breaks and delivers a few solid blows. Joey asks, “What does it prove?” Jake’s face is lightly spattered with blood, yet he cannot answer. Perhaps Jake unconsciously wants to demonstrate how he can stand a beating and even enjoys the punishment, given his feelings of inadequacy; or perhaps the inflicted physical pain removes the emotional sting of inferiority, albeit briefly. Throughout the remainder of the film, the boxer’s interiority materializes through physical violence, most pointedly in the ring, but also in domestic abuse and self-abuse.

LaMotta’s insecurities and paranoia construct the drive that makes him an unstoppable fighter. The film touches on LaMotta’s impressive record, but this is not a biography in the traditional sense. Scorsese is more interested in theme, and using the boxing matches to inform LaMotta’s behavior in his personal life, and vice versa. To put it simply: Everything is a fight. Whether unleashed on his wife or brother, LaMotta attacks them all with the same ferocity he would an adversary, beating down his rivals at home or in the ring. The film’s scenes alternate between intimate moments in the boxer’s Bronx apartment, particularly in the bedroom, and the resultant bloody pounding when he charges onto his opponent. How this symbolic relationship between settings finds dramatic balance remains the film’s most triumphant symbolism. Rapt with covetous fury and uncertainty, LaMotta channels his domestic frustrations in the boxing ring, where his own personal therapy session or confessional translates his pain into physical absolution and punishment. The scenes inside the ring remain more memorable than other boxing films because Scorsese places his audience into the points of view of LaMotta and his opponents—he forces us to take punches and give them, creating an immersive experience.

Many of LaMotta’s violent outbursts relate to his own obsessions and insecurities with his love life. At the outset, LaMotta is married to a wife for whom he has no respect. One day he spots a young girl at the area pool. The 15-year-old Vickie (Cathy Moriarty) earns the description of “neighborhood girl,” a nice way of saying she knows her way around the block. Jake avoids the association and looks at her from a distance in awe, the camera’s slow-motion gaze passing over her. She looks ten years older than her age (Moriarty was 19 at the time), and around her swarm a throng of neighborhood men like Salvy Batts (Frank Vincent), a Mafioso. After a brief courtship, Jake remarries to Vickie, but he refuses to bed his new wife so as not to release any pent-up aggression before a fight. Part of him resents her sexuality, even though she attracts him so—what Freud might call a “Madonna-whore complex.” Consumed by the suspicion that she cheats on him, he watches her closely, misreading her innocent comments and not-so-innocent kisses from neighborhood friends. When she remarks that Jake’s new opponent Tony Janiro (Kevin Mahon) is “good-looking,” Jake destroys the man’s face in the ring with a brutal pummeling in a jealous rage, at which point a Mob boss in the audience announces, “He ain’t pretty no more.”

Many of LaMotta’s violent outbursts relate to his own obsessions and insecurities with his love life. At the outset, LaMotta is married to a wife for whom he has no respect. One day he spots a young girl at the area pool. The 15-year-old Vickie (Cathy Moriarty) earns the description of “neighborhood girl,” a nice way of saying she knows her way around the block. Jake avoids the association and looks at her from a distance in awe, the camera’s slow-motion gaze passing over her. She looks ten years older than her age (Moriarty was 19 at the time), and around her swarm a throng of neighborhood men like Salvy Batts (Frank Vincent), a Mafioso. After a brief courtship, Jake remarries to Vickie, but he refuses to bed his new wife so as not to release any pent-up aggression before a fight. Part of him resents her sexuality, even though she attracts him so—what Freud might call a “Madonna-whore complex.” Consumed by the suspicion that she cheats on him, he watches her closely, misreading her innocent comments and not-so-innocent kisses from neighborhood friends. When she remarks that Jake’s new opponent Tony Janiro (Kevin Mahon) is “good-looking,” Jake destroys the man’s face in the ring with a brutal pummeling in a jealous rage, at which point a Mob boss in the audience announces, “He ain’t pretty no more.”

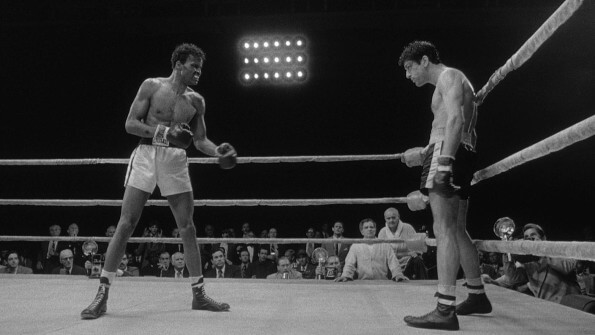

LaMotta’s bout with Janiro is just one of nine boxing matches in Raging Bull. Each defies the standard Hollywood technique of placing the audience on the outside, looking in, from the view of a spectator. Films such as Kid Galahad (1937) and Gentleman Jim (1942) create an understanding of the full space within and around the boxing ring, recapturing the experience of watching a boxing match from the audience. By contrast, Scorsese considers the ring a stage where LaMotta’s personal life plays out in symbolic terms. He places his viewer inside the ring, experiencing LaMotta’s subjective perspective from shots that regularly take the boxer or his opponent’s point-of-view in a manner recalling the flashbacks to boxing matches in John Ford’s The Quiet Man (1952). “I wanted to do the ring scenes as if the viewers were the fighter and impressions were the fighter’s,” Scorsese confirms. In actuality, Scorsese and De Niro had no real interest in the sport. “One sure thing was that it wouldn’t be a film about boxing,” the director announced. “We didn’t know a thing about it and it didn’t interest us at all.” Rather, the ring “becomes equivalent to inside Jake’s psyche,” as scholar Leger Grindon observes, noting their symbolic intent in the screenplay. In that sense, the challenge of Raging Bull was using the boxing sequences in expressive ways to reflect LaMotta’s inner state.

The fights, spanning a period from 1941 to 1951, when LaMotta lost his middleweight title, create a series of lyrical parallels that capture the character’s interiority. LaMotta’s masculine pride keeps him from communicating with Vickie or Joey, and so he must pour out his internalized anger, fear, and desire in the ring. Scorsese recognizes the relationship between sport and expression, and he employs an artistically exaggerated form to depict LaMotta’s intensified experience in his fights. Along with editor Thelma Schoonmaker’s brilliant arrangement of cinematographer Michael Chapman’s images, Scorsese’s point-of-view shots move with the reality of each punch. A landed blow might even cause the frame to tumble or fall. Unlike various entries in the Rocky franchise, which feature erratic fighting choreographed into screen chaos, Scorsese storyboarded the bouts in Raging Bull so his almost dreamlike visual techniques would have a precise psychological meaning for LaMotta. This includes adjusting the size of the ring from claustrophobic to expansive, not according to accuracy but as the dramatic moment of each scene demanded. For instance, when LaMotta’s personal life is in shambles, the ring seems narrowed and punishing, whereas the opposite is true for the boxer’s few moments of control.

Set in a smoky, noisy haze, Scorsese’s bouts are propelled by the dramatic subtext and how the filmmaking consciously reflects LaMotta’s state of mind. “Whatever control and passion LaMotta could bring to his life, he could only bring it to his fighting in the ring,” Chapman explains. The film does not chronicle LaMotta’s boxing career through these matches; rather, the scenes inform his damaged ego through the allegory of boxing. Raging Bull avoids dwelling on LaMotta’s training routine or fight strategy, and some boxing matches amount to no more than a few precisely chosen stills by Schoonmaker. But each has a symbolic intent beyond simple biographical detail. Above all, his fights against nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson prove the most representative. LaMotta’s two fights against Robinson in 1943 are framed against scenes with Vickie. The first fight is preceded by LaMotta feeling victorious for bedding Vickie, and he defeats Robinson in the ring. The second follows a scene where LaMotta stops kissing Vickie and drops ice water down his shorts, preserving his strength for a rematch against Robinson. But his failure to dominate Vickie in the bedroom leads to his failure in the ring—although Robinson never knocks LaMotta down, the judges rule against him. After, Scorsese shows LaMotta dipping his bruised hands in ice water, a clear parallel for his iced genitals in the bedroom scene. In this way, each of the boxing matches in the film works in tandem with the dramatic scenes framing it.

Set in a smoky, noisy haze, Scorsese’s bouts are propelled by the dramatic subtext and how the filmmaking consciously reflects LaMotta’s state of mind. “Whatever control and passion LaMotta could bring to his life, he could only bring it to his fighting in the ring,” Chapman explains. The film does not chronicle LaMotta’s boxing career through these matches; rather, the scenes inform his damaged ego through the allegory of boxing. Raging Bull avoids dwelling on LaMotta’s training routine or fight strategy, and some boxing matches amount to no more than a few precisely chosen stills by Schoonmaker. But each has a symbolic intent beyond simple biographical detail. Above all, his fights against nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson prove the most representative. LaMotta’s two fights against Robinson in 1943 are framed against scenes with Vickie. The first fight is preceded by LaMotta feeling victorious for bedding Vickie, and he defeats Robinson in the ring. The second follows a scene where LaMotta stops kissing Vickie and drops ice water down his shorts, preserving his strength for a rematch against Robinson. But his failure to dominate Vickie in the bedroom leads to his failure in the ring—although Robinson never knocks LaMotta down, the judges rule against him. After, Scorsese shows LaMotta dipping his bruised hands in ice water, a clear parallel for his iced genitals in the bedroom scene. In this way, each of the boxing matches in the film works in tandem with the dramatic scenes framing it.

Scorsese’s use of symbolism extends to his choice of black-and-white photography in Raging Bull, which, given his potent use of color, namely red, in other films, may seem unnatural for his filmmaking style. Apart from removing the actual color, the choice does nothing to reduce the film’s power—quite the opposite. Scorsese’s friend and idol Michael Powell inspired the choice after seeing rushes of De Niro’s gym routine; he considered the spraying blood and bright red gloves and resolved there was too much of the one color. Released in the era when the comparatively gentle fighting of Rocky Balboa won over America’s heart, Scorsese presented the bloodiest fisticuffs of any boxing film. No doubt the director felt some reluctance about portraying that much blood onscreen, with sponges hidden in boxing gloves and tubes under hair spewing fluids out in heavy streams and sprays as the actors make contact. Blood and sweat seem to drench the boxers, leaving the experience more visceral than any boxing matches put on film before or since, regardless of the absence of color. Ultimately, colors would have taken away from the symbolic drama of the images. Although Chapman cites crime scene photographer Wee Gee for his visual style—Chapman spent over $20,000 in vintage flash bulbs for a distinctive Scorsesean effect of reporters snapping photos—much of Raging Bull is metaphorical, and the black-and-white photography simultaneously captures reality and a psychological space to incredible effect.

Scorsese’s use of black-and-white film stock also coincides with his campaign for better film preservation, an aspect of his career that arguably challenges his directorial work in terms of prestige in the film industry. Upon the film’s eventual release on the festival and college lecture circuit, Scorsese called out Kodak to improve their film stock to prevent color from fading and demanded restorative efforts on films made in the last few decades that had already begun to diminish. By releasing Raging Bull in black-and-white to coincide with his restoration campaign, he knowingly linked his film to a discussion about film preservation and raised awareness about decaying film elements. The artistic choice of black-and-white was considered by many as a challenge to the film industry’s disregard for quality color film stock. Raging Bull, then, served as a sample of what all filmmakers should be using if no alternative to the then-standard cheap color stock was provided. Shortly thereafter, Kodak began supplying studios with stock that better preserves the original color. Scorsese has continued this push for film preservation throughout his career, aligning with The Film Foundation and The World Film Foundation to fund the restoration of many classic and forgotten films.

Raging Bull’s aural design is just as intricate as its visuals. Delivering an audible wallop on par with the depicted violence, Scorsese’s use of sound effects jars the senses and adds a dramatic layer to the storytelling. Camera bulbs chink, fists crunch faces, and the audience roars through it all, each sound created from a different element. Almost none of the sounds came from soundman Frank Warner’s library of effects, and certainly not from their depicted source. Rather, panes of glass, smashed fruit, animal cries, and gunshots cover the audio-frenzied fight scenes, the complexity of which extended the eight weeks of planned sound mixing twofold. Scorsese leaves the viewer in a virtual state of shell shock from the ensuing exchanges between the audio thwaps and snaps of the boxing scenes. The effect furthers the viewer’s immersion into LaMotta’s subjective perspective through moments of aural disorientation. However, in several pointed scenes, Scorsese and Warner drop the sound completely to achieve a moment of clarity or dream, only to come back with a harsh crack. To preserve the film’s aural uniqueness, Warner burned the individual recorded elements after the effects track was created and maintained secrecy around the source of these sounds. As a result, no other picture will ever sound the same as Raging Bull.

Raging Bull’s aural design is just as intricate as its visuals. Delivering an audible wallop on par with the depicted violence, Scorsese’s use of sound effects jars the senses and adds a dramatic layer to the storytelling. Camera bulbs chink, fists crunch faces, and the audience roars through it all, each sound created from a different element. Almost none of the sounds came from soundman Frank Warner’s library of effects, and certainly not from their depicted source. Rather, panes of glass, smashed fruit, animal cries, and gunshots cover the audio-frenzied fight scenes, the complexity of which extended the eight weeks of planned sound mixing twofold. Scorsese leaves the viewer in a virtual state of shell shock from the ensuing exchanges between the audio thwaps and snaps of the boxing scenes. The effect furthers the viewer’s immersion into LaMotta’s subjective perspective through moments of aural disorientation. However, in several pointed scenes, Scorsese and Warner drop the sound completely to achieve a moment of clarity or dream, only to come back with a harsh crack. To preserve the film’s aural uniqueness, Warner burned the individual recorded elements after the effects track was created and maintained secrecy around the source of these sounds. As a result, no other picture will ever sound the same as Raging Bull.

Scorsese’s best utilized special effect, however, remains the remarkable performance given by Robert De Niro, whose longstanding union with the director generated some of the finest work in their respective careers. More than any audio or visual artistry the production contains, those tricks of the trade work to support De Niro’s uncanny transformation. On and off set, De Niro worked closely with credited “Consultant” Jake LaMotta, picking up his mannerisms, and even taking care of the broken soul on occasion. Though, LaMotta was kept on the set only during the ten weeks it took to shoot the fighting scenes, in which time De Niro took instruction on how to move and guard, where to hold his hands and how to throw a punch. Even when scrutinized in side-by-side comparisons between Scorsese’s film and LaMotta’s vintage fight reels, the actor’s manifestation of the boxer’s fighting style is flawless. LaMotta remained accessible to De Niro throughout the shoot, although Scorsese refused to allow him to observe the dramatic scenes given the liberties the filmmakers intended to make on their subject’s life. For the later scenes featuring a heavier LaMotta, the production took a four-month hiatus while De Niro “ate his way around Northern Italy and France,” adding on the necessary girth to weigh the part. De Niro gained some 50 pounds, while Scorsese and Schoonmaker put together everything but De Niro’s heavier scenes. In this archetypal actor’s metamorphosis, the one against which every subsequent actor’s physical transformation would be judged, De Niro goes from the lean physique of a champion athlete to an overfed has-been. This bloated version of LaMotta gives up fighting and runs his own Miami club, called “Jake LaMotta’s” no less.

The film’s second half charts how the boxer’s destructive jealousy and blinding pride contrast his desire for redemption through pain, fuelling the recurrent theme in Scorsese’s pictures of Christian guilt or self-punishment. Jake becomes lazy and overconfident after earning his championship belt. He then attacks Joey, suspecting his brother and wife are having an affair. Severing his relationship with his brother, LaMotta’s remorse overcomes him when he defends his title against Sugar Ray Robinson in 1951. LaMotta’s stubborn pride has ruined his family, and the boxer’s desire to atone will bring his career inside the ring to an end. Not fighting back, LaMotta sentences himself to a fifteen-round beating. Blow after blow and LaMotta does not go down, and he seems disappointed, even annoyed that Robinson’s punches do not relieve his remorse. “C’mon, Ray. C’mon,” he beckons. Though the real LaMotta claims he was playing possum, Scorsese shows us LaMotta literally asking for it in an almost Christlike fashion. The result of his invited punishment drips off the ropes. Scorsese tells the famous story: “Jonathan Demme gave me a portrait of Jake made by a folk artist and around the edge of this piece of slate was carved, ‘Jake fought like he didn’t deserve to live.’ Exactly, I made a whole movie and this guy did it in one picture!” But alas, LaMotta never receives the redemption that he desperately needs.

When LaMotta finds himself arrested and thrown in jail, having tried and failed to pawn off the jewels in his championship belt for bail, he slams his head and fists against the cell wall, crying “Why!” and “You’re so stupid!” His archenemy all along was himself, not Joey or Sugar Ray Robinson, and unconsciously he knows this. Later, the former boxer, thick-necked and breathing heavy, performs his grating lounge act in a hole-in-the-wall dive. Scenes of him practicing a monologue from On the Waterfront (1954) bookend the film. The audience sees De Niro doing LaMotta doing Brando doing Terry Malone. And somehow that conversion resists being merely a series of parodies stacked on top of one another because of De Niro’s brilliant translation. His performance eliminates the “acting” in the equation, so what we see is LaMotta identifying with the transcendence of his own words. Here LaMotta gives the “Coulda been a contender” speech, wherein Malone confronts his brother Charlie’s betrayal. “It was you, Charlie,” LaMotta says, looking deep into the mirror at himself, presenting the very moment when this broken boxer understands his own cruelly self-deprecating nature. This performance-within-a-performance effect took some nineteen takes to accomplish and represents some of the most extraordinary acting ever put to celluloid.

When LaMotta finds himself arrested and thrown in jail, having tried and failed to pawn off the jewels in his championship belt for bail, he slams his head and fists against the cell wall, crying “Why!” and “You’re so stupid!” His archenemy all along was himself, not Joey or Sugar Ray Robinson, and unconsciously he knows this. Later, the former boxer, thick-necked and breathing heavy, performs his grating lounge act in a hole-in-the-wall dive. Scenes of him practicing a monologue from On the Waterfront (1954) bookend the film. The audience sees De Niro doing LaMotta doing Brando doing Terry Malone. And somehow that conversion resists being merely a series of parodies stacked on top of one another because of De Niro’s brilliant translation. His performance eliminates the “acting” in the equation, so what we see is LaMotta identifying with the transcendence of his own words. Here LaMotta gives the “Coulda been a contender” speech, wherein Malone confronts his brother Charlie’s betrayal. “It was you, Charlie,” LaMotta says, looking deep into the mirror at himself, presenting the very moment when this broken boxer understands his own cruelly self-deprecating nature. This performance-within-a-performance effect took some nineteen takes to accomplish and represents some of the most extraordinary acting ever put to celluloid.

Released in 1980, Raging Bull earned Academy Awards for De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker. And though Oscar overlooked the film and its director in favor of Robert Redford’s Ordinary People, subsequent assessments from the American Film Institute and Sight & Sound magazine rank Scorsese’s film among the greatest ever made. It’s often considered Scorsese’s best film for how it condenses his auteurist themes into a singular case. Indeed, Scorsese’s films continually reflect on masculine drives standing in opposition of faith or inborn morality, producing a conflicted and thus dynamic character who ultimately punishes himself to resolve his inner turmoil: Mean Streets features Harvey Keitel’s small-time hood balancing his criminal life with his devotion to God, holding a flame to his hand in hope of absolution. Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver expresses displacement within New York City, more specifically his reserved attraction to an underage prostitute by saving her in a suicidal pimp killing spree, which he tragically survives. Most controversially, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) featured Willem Dafoe’s Jesus reflecting on his own crisis of faith and desire to rebel against his fate, and he resolves both concerns through his affliction on the cross. The examples could go on and on, and common throughout them is Scorsese’s interest in humanity’s relationship to spirituality.

Nowhere in Martin Scorsese’s career have these themes found more precise descriptions than in Raging Bull. Jake LaMotta is a personification of Scorsese’s ongoing thesis, and by placing the viewer inside the ring with the character, the director forces identification with him—unpleasant though it may be. Through De Niro’s performance and the vast array of visual and aural techniques used to immerse the viewer in LaMotta’s subjective perspective, Scorsese explores how masculine identity clashes with spiritual absolution, resulting in a dramatically conflicted character. This would become a theme found in later pictures, including Goodfellas (1990), Cape Fear (1991), The Age of Innocence (1993), Casino (1995), Shutter Island (2010), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), and The Irishman (2019) But Raging Bull should be thought of as an embodiment that captures the recurrent critique of masculinity that pervades many of Scorsese’s films, which the director renders with equal measures of stylistic expressiveness and realism. By understanding Raging Bull, his audience consequently perceives the depth and intensity behind all Scorsese pictures, and for that, it operates not only as a moving drama, but also as a thematic instruction manual for one of cinema’s greatest filmmakers.

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron (editor). A Companion to Martin Scorsese, Revised. First Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021.

Christie, Ian; Thompson, David (edited by). Scorsese on Scorsese. Revised Edition. Faber, 2003.

Galloway, Stephen. “Martin Scorsese’s Journey From Near-Death Drug Addict to ‘Silence.’” The Hollywood Reporter, 8 December 2016. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/martin-scorsese-interview-death-drug-addict-silence-953300/. Accessed 20 June 2022.

Leger, Grindon. “Filming the Fights: Subjectivity and Sensation in Raging Bull.” A Companion to Martin Scorsese. Revised Edition. Edited by Aaron Baker. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021, pp. 408-431.

Scorsese, Martin; Henry, Michael. A Personal Journey Through American Movies. Hyperion, 1997.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review