The Definitives

Portrait of Jennie

Essay by Brian Eggert |

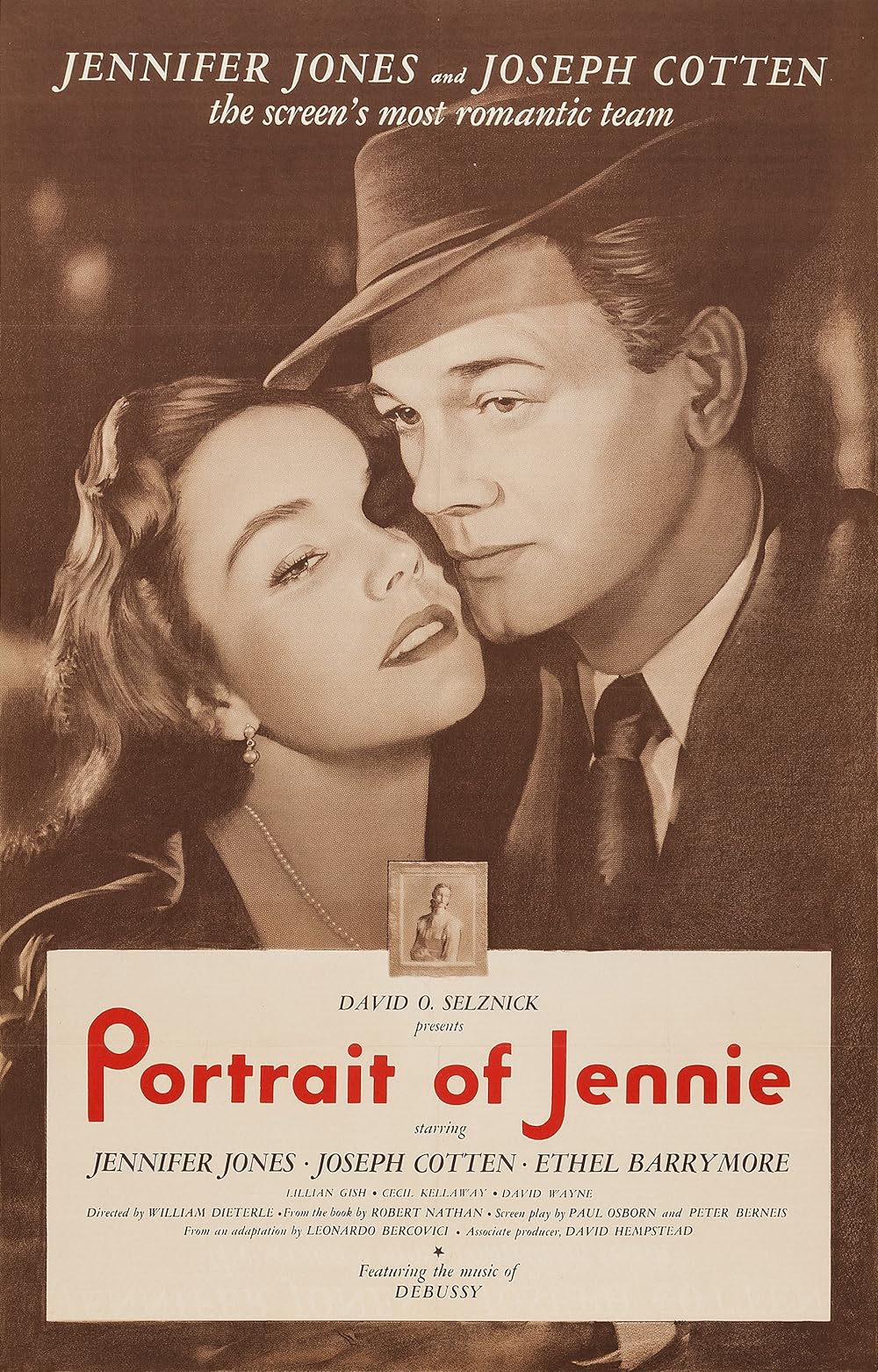

Portrait of Jennie opens with a strange and remarkable sequence. A voice introduces the story and its themes, alternating between humanity’s grand questions about time, space, and mortality, and then quotes from the literary works of Euripides and Keats. “Science tells us that nothing ever dies but only changes,” the voice says, “that time itself does not pass, but curves around us, and that the past and the future are together at our side forever.” Images of billowing clouds shot through curved lenses fade into one another as the voice continues: “Out of the shadows of knowledge, and out of a painting that hung on a museum wall comes our story, the truth of which lies not on our screen, but in your heart.” By the time the lofty prologue is over, there is no telling what might follow. What is so remarkable about this opening, written by Ben Hecht at the behest of producer David O. Selznick, is that, in all its learned pretensions, it suitably prepares the viewer for the film that follows. It’s an opening that even Selznick believed was “too abstruse and highfalutin’ for complete audience understandability,” but nonetheless established the uniqueness of the picture. It situates Portrait of Jennie, an adaptation of the 1940 novella by Robert Nathan, into the realm of romantic fantasy, yet it implies the film’s story is true and merely presents the details as they are known. Curiously, it also suggests that the viewer must take a leap of faith.

Any film that begins the way this one does is “a complete departure in motion picture entertainment,” as the original trailers declared. Few Hollywood productions from the era of its release, in 1948, demand so much of the audience. Not only does the story involve a romance that transcends traditional linear time models and brings into question everything the viewer knows about time and space, but its film grammar makes bold advances and departures from the Classical Hollywood modes of the period. Portrait of Jennie is at once made “in a tradition of quality” associated with The Selznick Studio, the makers of A Star is Born (1937) and Rebecca (1940), and experimental in its uses of framing devices and narrative ambiguity. It’s a romance that seems to take place in The Twilight Zone and follow the rules of a Lynchian or Nolan-esque scenario, wherein time is circular and paradoxical. It contains two sets of distinct voiceovers, painterly visual motifs, and enough elusive story mechanics to justify the film’s opening sentiment, which ostensibly warns that the story will not make any sense in logical terms. And yet it asserts, and it is right to do so, that the audience will nonetheless feel moved by the film.

After the initial voiceover, Portrait of Jennie features another voice, that of starving artist Eben Adams, played by Joseph Cotten with everyman charm. He narrates his memories that begin in the winter of 1934, the year he meets Jennie (Jennifer Jones). She first appears to him in a park as an adolescent girl speaking with a slight lisp. The sound of a theremin winding under the score implants a curiosity about the encounter. Eben points out that the sun is setting and the unattended child should be headed home. “I don’t have to go home yet,” she replies. “Nobody’s ready for me.” She seems immediately comfortable with this stranger, adding, “Anyway, you’re with me.” Jennie’s behavior might just be precocious, given how confident she behaves when looking over the contents of Eben’s portfolio and how she seems to “just know” that his paintings depict the Land’s End Light, a lighthouse on Cape Cod. The odd encounter continues with Jennie wishing they could “always be together,” and her certainty that Eben will one day paint her portrait. Crossing paths with Jennie somehow invigorates Eben’s work as a painter. Miss Spinney (Ethel Barrymore), a sympathetic art dealer who works closely with gallery owner Matthews (Cecil Kellaway), tells Eben that his art will continue to be lifeless until he finds an impassioned subject other than landscapes. To that end, Jennie is Eben’s muse. She leaves him invigorated, artistically speaking. After their first encounter, he secures a commission to paint a mural in an Irish pub in an amusing subplot. Later, he sketches a portrait that Miss Spinney buys for the gallery.

After the initial voiceover, Portrait of Jennie features another voice, that of starving artist Eben Adams, played by Joseph Cotten with everyman charm. He narrates his memories that begin in the winter of 1934, the year he meets Jennie (Jennifer Jones). She first appears to him in a park as an adolescent girl speaking with a slight lisp. The sound of a theremin winding under the score implants a curiosity about the encounter. Eben points out that the sun is setting and the unattended child should be headed home. “I don’t have to go home yet,” she replies. “Nobody’s ready for me.” She seems immediately comfortable with this stranger, adding, “Anyway, you’re with me.” Jennie’s behavior might just be precocious, given how confident she behaves when looking over the contents of Eben’s portfolio and how she seems to “just know” that his paintings depict the Land’s End Light, a lighthouse on Cape Cod. The odd encounter continues with Jennie wishing they could “always be together,” and her certainty that Eben will one day paint her portrait. Crossing paths with Jennie somehow invigorates Eben’s work as a painter. Miss Spinney (Ethel Barrymore), a sympathetic art dealer who works closely with gallery owner Matthews (Cecil Kellaway), tells Eben that his art will continue to be lifeless until he finds an impassioned subject other than landscapes. To that end, Jennie is Eben’s muse. She leaves him invigorated, artistically speaking. After their first encounter, he secures a commission to paint a mural in an Irish pub in an amusing subplot. Later, he sketches a portrait that Miss Spinney buys for the gallery.

The next time Eben sees Jennie, a few days later while ice skating in Central Park, she appears several years older and talks of going off to college soon. When she asks Eben if he will wait for her, one suspects he will not have to wait long. With each subsequent encounter over the changing seasons of 1934, Jennie appears older. Several years seem to pass for her between their meetings, always with lovelorn words about their eventual coupling. At first, it’s unclear whether Jennie is a ghost or a time-traveler. She might be a figment of Eben’s imagination, a psychological response to Miss Spinney’s suggestion that Eben must find inspiration to become a better painter. No one else can see her, after all. But answers to the audience’s questions never come in Portrait of Jennie, and that is by design. During early story conferences, Selznick sought a balance; he wanted ambiguity about Jennie’s supernatural presence, but not so much that the audience would think Eben was a madman. The audience would have to be convinced of Eben’s sanity and the love between Eben and Jennie, and both would require a fantastical leap. And so, Eben discovers that Jennie had once existed two decades before, but she died during a hurricane in 1910. Due to some romantic notions about true love transcending time and space, Eben and Jennie have found each other. Jennie is aware of her status outside of time and how their relationship will end. She knows in advance that Eben will paint her portrait and seems aware that they belong together.

All of this is signaled when Jennie first appears as a child to Eben. She sings him a melancholy tune that hints at time folding over on itself: “Where I come from nobody knows, and where I am going everything goes. The wind blows, the sea flows. Nobody knows. And where I am going nobody knows.” The screen story, which diverts from Nathan’s source material, takes place somewhere outside of our understanding, a space in which our imagination is piqued by the film’s sustained mystery. If the opening narration indicates anything in its opaque way, it suggests the intangible power of love to reach beyond known scientific limitations. This idea is encapsulated by Jennie, played by Selznick’s muse and wife. When Matthews looks at Eben’s sketch of Jennie and declares, “There ought to be something timeless about a woman,” he might be hinting at the film’s abstraction of time through love. But then, Portrait of Jennie is loaded with such dialogue, usually spoken by Jennie in half-awareness of her travels through time. When Eben asks the young Jennie if he might visit her at home, she replies, “I don’t think there’s a place you can come and see me, not yet.” She also has bewildering remarks such as, “Listen to the stars coming out,” and “Time doesn’t matter. It’s always tomorrow.” Her fuzzy awareness of her own metaphysical presence remains a constant point of fascination.

Portrait of Jennie may not always make logical sense, but its chimerical treatment of time, elliptical structure, and aching love story supply the material of great cinema. Gilles Deleuze wrote that “the disturbances of memory and the failures of recognition” deliver the essential and most valuable experiences of cinema. Deleuze argued that images alone do not make up the power of cinema; rather, it is the intervals between images that define their relationship and communicate to the audience a complete idea. Deleuze explains this haunting, in-between effect through instances of déjà vu, vague impressions of the past that move at “dizzying speed,” and dream imagery—an elusive atmosphere that confounds and intrigues, but it also arrives at understanding. He argues that recognition of the literal remains less powerful than the virtual, the phantasmic images of the unconscious. This argument also lends itself to breaks in linear time. The type of imagery Deleuze describes was explored by European filmmakers in the 1920s, with German Expressionists using visual sensations that were unbodied, abstract, and drawn from dreams. Before the Second World War, Hollywood had been situated in literalized visual storytelling through what Deleuze calls simple action-images. But during and after the war, when European filmmakers fled the Nazis and made their way to Tinsel Town, they brought their aesthetic tricks to the studios. Throughout the 1940s, Hollywood movies became less about recognition and more about the space in-between the known and the unknown. Portrait of Jennie inhabits this space.

Portrait of Jennie may not always make logical sense, but its chimerical treatment of time, elliptical structure, and aching love story supply the material of great cinema. Gilles Deleuze wrote that “the disturbances of memory and the failures of recognition” deliver the essential and most valuable experiences of cinema. Deleuze argued that images alone do not make up the power of cinema; rather, it is the intervals between images that define their relationship and communicate to the audience a complete idea. Deleuze explains this haunting, in-between effect through instances of déjà vu, vague impressions of the past that move at “dizzying speed,” and dream imagery—an elusive atmosphere that confounds and intrigues, but it also arrives at understanding. He argues that recognition of the literal remains less powerful than the virtual, the phantasmic images of the unconscious. This argument also lends itself to breaks in linear time. The type of imagery Deleuze describes was explored by European filmmakers in the 1920s, with German Expressionists using visual sensations that were unbodied, abstract, and drawn from dreams. Before the Second World War, Hollywood had been situated in literalized visual storytelling through what Deleuze calls simple action-images. But during and after the war, when European filmmakers fled the Nazis and made their way to Tinsel Town, they brought their aesthetic tricks to the studios. Throughout the 1940s, Hollywood movies became less about recognition and more about the space in-between the known and the unknown. Portrait of Jennie inhabits this space.

Selznick had been attracted to the European aesthetic for some time. He had already succeeded in convincing England’s premier director, Alfred Hitchcock—who had worked for the German studios and employed their techniques in his British thrillers—to move to Hollywood. Their first collaboration was Rebecca, a film haunted by uncertainty, memories, and the past. When Selznick searched for a director for Portrait of Jennie, he settled on William Dieterle, who was among many European filmmakers to immigrate to the United States and introduce their style into Hollywood motion pictures. Dieterle had hoped to escape the worsening political situation in Germany, and at Warner Bros. he became a studio journeyman recognized for his capably made biographies, such as The Life of Emile Zola (1937). But if anything in Dieterle’s career would have convinced Selznick that he could make Portrait of Jennie, it might have been The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), a comic fantasy based on Faust. For his cast, Selznick flirted with Vivian Leigh as Jennie opposite her husband, Laurence Olivier, a notion that would have upset Jones had he pursued it. He even considered using Shirley Temple, a choice that would have used the audience’s familiarity with the former child star to the film’s advantage. Instead, he recast the stars from Duel in the Sun, the producer’s overcooked Western from 1946, with Jones and Cotten. The literate screenplay is the product of several contributors writing and rewriting on Selznick’s order. Peter Berneis (The Glass Menagerie, 1950) completed the first draft, followed by Leonardo Bercovici (The Bishop’s Wife, 1947), then Paul Osborn (The Yearling, 1946), while Ben Hecht and Selznick himself made uncredited changes.

As usual, Selznick obsessed over every aspect of the disastrous production, whose schedule overages elevated the original budget of $1.5 million to such heights that the producer considered abandoning the picture altogether—the losses would have been too significant, however. The trouble began during early story conferences when the filmmakers could not agree what was real and what was a fantasy; these debates continued well into the shoot. Still, Selznick insisted, rightly so, that Jennie’s “ethereal quality evaporates” if anyone other than Eben sees her, though he could not agree with himself or others whether Jennie ever existed in the real world. At the same time, he saw Jennie and Eben’s relationship as an expression of his own romance with the much younger Jones—and sure enough, she gave the kind of excellent performance that made Selznick fall deeper in love. They married the year after Portrait of Jennie debuted. Meanwhile, problems with the shoot, which was filmed on location in New York and the West Coast, drove up costs and required story changes. Whole scenes were removed because, for one reason or another, the cast and crew were not producing. A scene where Jennie dances by a stream took four days to choreograph and shoot, but only one take was captured, and that was scrapped. Given the rewrites, even after scenes had been shot, post-sync dialogue was used to plug story holes or add testaments of love where none were recorded. Selznick believed the production was “doomed to be one of the most awful experiences any studio ever had.” In his landmark biography of Selznick, David Thomson wrote the film “killed a part of David’s love for picture-making” and compelled Selznick to leave Hollywood to produce films in Europe—beginning with British filmmakers like Carol Reed for The Fallen Idol (1948) and The Third Man (1949), and then The Archers, Michael Powell and Emmerich Pressburger, for Gone to Earth (1950).

Portrait of Jennie remains an abnormal film, made with an unusual blend of voiceover and visual devices, in part from Selznick’s faltering and rethinking of his material. In his memos, he considered various techniques as devices to frame the past. He deliberated over using narration from a supporting character, an omniscient narrator, and in his indecision, he even considered scrapping voiceover altogether. He eventually resolved to give the film its loaded foreword from a cinematic emcee, complete with literary quotes. This is followed by Eben’s voiceover throughout the entirety of the film. But Eben’s narration remains puzzling. Usually, a first-person narrator recalls their past, but Portrait of Jennie is not a typical memory. The story takes place between two stations in time: Eben, as a narrator, looks back at the story as his past, but Jennie materializes from the past to affect the present. The substance of the film, then, unfolds somewhere in the middle between Eben’s perspective as a narrator and Jennie’s origins in the early twentieth century. The viewer might feel a sense of floating outside of time, looking at three timelines at once. In addition to the voiceover devices, the production’s liberal use of post-sync dialogue also creates a disembodied effect, although this element is no doubt unintended by the filmmakers. Given Selznick’s persistent tinkering with the script, Portrait of Jennie features a surprising number of scenes where the dialogue does not match the actors’ lips, or where the actors’ mouths do not move at all despite the dialogue on the soundtrack. The result, especially noticeable in the climactic tidal wave sequence, gives the impression of two spirits speaking to each other across time, their bodies mere vessels for two souls that belong together. The effect is extratextual in nature, but it blends decidedly well with the film’s themes of ephemeral desire.

Portrait of Jennie remains an abnormal film, made with an unusual blend of voiceover and visual devices, in part from Selznick’s faltering and rethinking of his material. In his memos, he considered various techniques as devices to frame the past. He deliberated over using narration from a supporting character, an omniscient narrator, and in his indecision, he even considered scrapping voiceover altogether. He eventually resolved to give the film its loaded foreword from a cinematic emcee, complete with literary quotes. This is followed by Eben’s voiceover throughout the entirety of the film. But Eben’s narration remains puzzling. Usually, a first-person narrator recalls their past, but Portrait of Jennie is not a typical memory. The story takes place between two stations in time: Eben, as a narrator, looks back at the story as his past, but Jennie materializes from the past to affect the present. The substance of the film, then, unfolds somewhere in the middle between Eben’s perspective as a narrator and Jennie’s origins in the early twentieth century. The viewer might feel a sense of floating outside of time, looking at three timelines at once. In addition to the voiceover devices, the production’s liberal use of post-sync dialogue also creates a disembodied effect, although this element is no doubt unintended by the filmmakers. Given Selznick’s persistent tinkering with the script, Portrait of Jennie features a surprising number of scenes where the dialogue does not match the actors’ lips, or where the actors’ mouths do not move at all despite the dialogue on the soundtrack. The result, especially noticeable in the climactic tidal wave sequence, gives the impression of two spirits speaking to each other across time, their bodies mere vessels for two souls that belong together. The effect is extratextual in nature, but it blends decidedly well with the film’s themes of ephemeral desire.

To this end, several tenuous fibers stretch across the temporal gap between Eben and Jennie. Eben experiences the pressure of time in his art. He is compelled to paint the Land’s End Light, the coastal island where Jennie died, long before he meets her as a girl. After their first encounter, he is also the carrier of Jennie’s scarf, an object she leaves behind on a park bench. He will continue to hold the item until she appears to him as an adult, when he gives her the scarf. She dies wearing it. As time passes and the anniversary of Jennie’s death approaches, Eben grows obsessed not just with completing his masterpiece, her portrait, but finding a way to keep them together. “Now I feel there’s another kind of distance, a crueler distance, a distance of yesterday and tomorrow and it frightens me,” he says. “It frightens me that there’s no way to bridge it.” He soon convinces himself that he can prevent her death from happening. If he arrives at the lighthouse and can reach across time to save Jennie, perhaps they can be together forever. His attempted rescue unfolds on a narrow island slammed by waves. Jennie fatalistically accepts that time has chosen to keep them apart but also connected in a supernatural way. Eben, though, desperately clings to her, until a wave rolls over them both. He awakes in a bed some time later, having been saved from Jennie’s fate. Miss Spivey sits at his bedside. Though no evidence remains to prove Jennie was at the lighthouse, she tells him, “You believe it, that’s all that matters.”

The climax itself is a rousing sequence for which Selznick pulled out all the stops. In one of his famous memos, Selznick wrote of his plans: “I hope to get a real D. W. Griffith effect out of this that will have tremendous dramatic power and enormous spectacular value, thereby adding a big showmanship element to the picture.” The sequence, designed by William Cameron Menzies, also contains an other-worldly element, as the black-and-white photography adopts a green tint as lightning strikes and mysterious cloud formations begin to surge. In the original theatrical exhibitions, the aspect ratio shifted as well, adjusting from the boxy Academy ratio to a widescreen frame, while the single-channel sound expanded to additional speakers throughout the auditorium that blasted the audience with sound. Given the decibel levels, Bosley Crowther’s review in The New York Times told moviegoers “to take a mental recess and have some cotton ready to stuff in your ears” before the sequence. Scale models and a massive water tank added to the scene’s grandness—one whose sheer scope compares to the burning of Atlanta in Selznick’s Gone with the Wind (1939). The special effects won Portrait of Jennie its only Oscar, but they also give way to the film’s fantastical peculiarities. The green tint, followed by the scenes shot with a reddish hue the next morning, recall the transition between worlds in The Wizard of Oz (1939). These are obvious examples, however. Consider also the brief moment earlier in the film, where Jennie ice skates toward Eben and the sun shining behind her renders her briefly semi-transparent. It’s an effect that flashes on the screen so quickly, you might miss it.

Layered underneath Portrait of Jennie’s innovative uses of time is another motif, this one entirely visual, that draws connections between fine art and motion pictures. The first images of New York City against Eben’s narration show the city with canvas texture, realized with a semi-transparent layer. The combined images of the city and the canvas appear to the viewer like a living painting. Though the effect might represent one of Eben’s pieces, Selznick also sought to elevate motion pictures from entertainment for the masses into the stratum of fine art. This ambition drove Selznick’s choice to adapt several great and widely celebrated works of literature that would instantly resonate with a viewer, not only because of their popularity but their status as respected works of literary art. He began with an adaptation of A.E.W. Mason’s The Four Feathers in 1929 and continued translating books to the screen with Anna Karenina (1935), David Copperfield (1935), A Tale of Two Cities (1935), The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938), and many others. If film could capture great works of literary art, it might be raised up to that echelon itself. Portrait of Jennie’s canvas overlay usually appears in transitional scenes, and the painterly motif is accompanied by yet another framing device. During the multifaceted prologue, a shot from The Metropolitan Museum of Art exterior fades into an art history book called The Paintings of Eben Adams, and opens to a page about his work, Portrait of Jennie. A similar effect, which returns to close out the film, was used by Hollywood in many based-on-a-book adaptations. This familiar device lends the film a storybook structure, as though the book, often opened with an invisible or off-screen hand, had been opened by the viewer for a cinematic experience every bit as cultured as reading a book.

Layered underneath Portrait of Jennie’s innovative uses of time is another motif, this one entirely visual, that draws connections between fine art and motion pictures. The first images of New York City against Eben’s narration show the city with canvas texture, realized with a semi-transparent layer. The combined images of the city and the canvas appear to the viewer like a living painting. Though the effect might represent one of Eben’s pieces, Selznick also sought to elevate motion pictures from entertainment for the masses into the stratum of fine art. This ambition drove Selznick’s choice to adapt several great and widely celebrated works of literature that would instantly resonate with a viewer, not only because of their popularity but their status as respected works of literary art. He began with an adaptation of A.E.W. Mason’s The Four Feathers in 1929 and continued translating books to the screen with Anna Karenina (1935), David Copperfield (1935), A Tale of Two Cities (1935), The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938), and many others. If film could capture great works of literary art, it might be raised up to that echelon itself. Portrait of Jennie’s canvas overlay usually appears in transitional scenes, and the painterly motif is accompanied by yet another framing device. During the multifaceted prologue, a shot from The Metropolitan Museum of Art exterior fades into an art history book called The Paintings of Eben Adams, and opens to a page about his work, Portrait of Jennie. A similar effect, which returns to close out the film, was used by Hollywood in many based-on-a-book adaptations. This familiar device lends the film a storybook structure, as though the book, often opened with an invisible or off-screen hand, had been opened by the viewer for a cinematic experience every bit as cultured as reading a book.

Structural variations aside, the mark of time travel and fantasy in Portrait of Jennie spelled its doom at the box-office. Crowther called it “deficient and disappointing in the extreme.” Even the score is a marvelous mix of high and low, relying on Debussy, and “The Afternoon of a Faun” above all, along with theramin music that recalls what would later become standard sounds in an Atomic Age science-fiction yarn (courtesy of Bernard Herrmann no less). Most fantasy films from this era were not taken seriously by critics or moviegoers. Even The Wizard of Oz was a notorious bomb. They were the stuff of low budgets and B-grade productions, sourced from pulp magazines and dime novels—a complete reversal from today’s saturated market of fantasy blockbusters. Occasionally, as David Bordwell observes in his book Reinventing Hollywood, Broadway would elevate the genre with something like Roger and Hammerstein’s Brigadoon (1947), about a Scottish village that appears once every hundred years for a single day. But it would take decades before fantasy became a mainstream genre. In any case, fantasies from this era often involve some element of time that reaches into the past and creates a sense of romantic longing, often with a grounded hero taking a leap into the supernatural in the name of love. This is true of Portrait of Jennie, but consider also Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), which reunites James Mason’s ghostly sea captain with Ava Gardner, the reincarnation of the wife he murdered in the seventeenth century. Gardner’s modern woman must not only fall in love but sacrifice herself for the cursed seaman before time runs out, otherwise he’s going back to Davy Jones’ Locker.

Both Portrait of Jennie and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman find their lovers separated by time and joined together by the fantastical. Whether the bond between Eben and Jennie is merely perceptive or actually physical remains uncertain, just as Jennie does. Sigmund Freud, whose psychoanalytic theories often appeared in Selznick productions of the 1940s, above all in Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), wrote about time, desire, and consciousness, and his ideas feel imprinted on Portrait of Jennie. Freud likened artistic creation, specifically creative writing, to a “day-dream” that originates in one’s memory, where “past, present, and future are strung together, as it were, on the thread of the wish that runs through them.” Romantic yearning, something Freud equates to wish fulfillment, conjures a perception of that wish. With this in mind, Jennie might be Eben’s wish—his ideal woman or someone he read about and suppressed his memory of; she might also be a ghost with some presence in the material world. If there’s evidence of Jennie’s existence outside of Eben’s desire or some newspaper clippings, it resides in her scarf, which Miss Spinney says was found next to him on the beach at Land’s End Light. It might also be an object Eben discovered in the park and assigned some meaning to. In the end, Eben’s artistic inspiration alone crystallizes Jennie’s legitimacy. One of the last shots shows three young students in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; they admire Eben’s painting (realized by painter Robert Brackman) and wonder if its subject was real. “What does it matter?” one of them wonders. “She was real to him, or she couldn’t look so alive.” Selznick ends the picture with a final shot in three-strip Technicolor of Eben’s painting hanging in a museum. The gorgeous full-color image presents a stark contrast to the black-and-white and color-tinted images that came before, serving as a step toward the truth explored by Keats in the opening: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

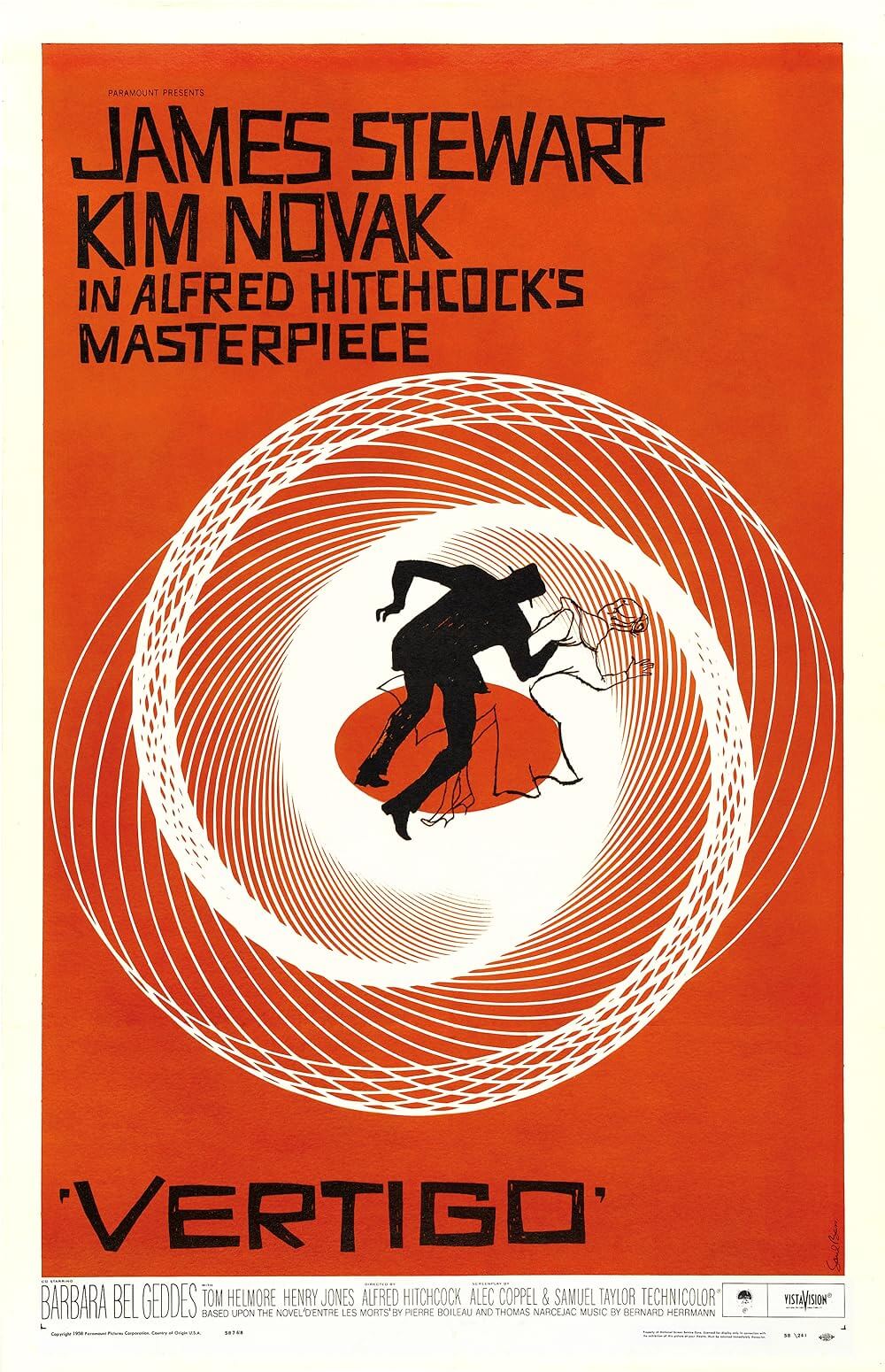

In addition to Portrait of Jennie, the power of desire and love has been shown to interrupt the linearity of time, the foundation of a subgenre of romances about time-traveling characters. Other examples of time-traveling romances include La jeteé (1963), and to some extent its remake 12 Monkeys (1995); Somewhere in Time (1980); The Lake House (2006); The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009); and About Time (2013). A case might even be made for the way Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) deals with memory as the substance of time and love in a relationship. Still, the film that comes to the forefront of one’s mind when watching Portrait of Jennie is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Though no actual ghost emerges in that film, nor does any time travel occur, James Stewart believes that Kim Novak’s Madeline is under the spell of Carlotta Valdez’s ghost, just as he believes later that Judy might somehow be able to reincarnate Madeline if only she dresses for the part. Both films blend romantic longing with the ethereal, or the possibility of the supernatural. Both feature a male protagonist obsessed with a woman whose place in time and space is elusive, at least to the main character. They also both contain a climactic moment on a staircase, in the lighthouse of Land’s End Light in Portrait of Jennie and the tower at Mission San Juan Bautista in Vertigo. They both feature green-tinted scenes, the storm sequence in Dieterle’s film and Madeline’s hotel room in Hitchcock’s. In many ways, Portrait of Jennie feels like a precursor to Vertigo, in the same way that Chris Marker called La jeteé a “remake” of Vertigo.

In addition to Portrait of Jennie, the power of desire and love has been shown to interrupt the linearity of time, the foundation of a subgenre of romances about time-traveling characters. Other examples of time-traveling romances include La jeteé (1963), and to some extent its remake 12 Monkeys (1995); Somewhere in Time (1980); The Lake House (2006); The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009); and About Time (2013). A case might even be made for the way Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) deals with memory as the substance of time and love in a relationship. Still, the film that comes to the forefront of one’s mind when watching Portrait of Jennie is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Though no actual ghost emerges in that film, nor does any time travel occur, James Stewart believes that Kim Novak’s Madeline is under the spell of Carlotta Valdez’s ghost, just as he believes later that Judy might somehow be able to reincarnate Madeline if only she dresses for the part. Both films blend romantic longing with the ethereal, or the possibility of the supernatural. Both feature a male protagonist obsessed with a woman whose place in time and space is elusive, at least to the main character. They also both contain a climactic moment on a staircase, in the lighthouse of Land’s End Light in Portrait of Jennie and the tower at Mission San Juan Bautista in Vertigo. They both feature green-tinted scenes, the storm sequence in Dieterle’s film and Madeline’s hotel room in Hitchcock’s. In many ways, Portrait of Jennie feels like a precursor to Vertigo, in the same way that Chris Marker called La jeteé a “remake” of Vertigo.

Having identified the numerous introductions, framing devices, applications of color, and arcane uses of temporality in Portrait of Jennie, it should be noted that, in another film, just one in the patchwork of techniques and narrative strategies would suffice. There is good reason for a viewer well-versed in Classical Hollywood’s production standards to question whether Selznick had put too much into the film (David Thomson stated plainly, “The picture is a travesty”) or he had finally made his magnum opus. While signs of Selnick’s persistent tinkering remain, the film is uncommonly more admirable for its oddities and occasional flaws, including the overuse of post-sync dialogue and supercilious opening quotes. Portrait of Jennie feels inspired for its haunting and romantic quality, the depth of Cotten’s yearning and Jones’ fatalistic yet undeterred love that eclipses all else. If aspects of the story or production seem occasionally unclear or rough around the edges, the truth of its beauty forces the viewer to ask “What does it matter?”—just like the young art student in the film’s last scene. Somehow, it all works, though perhaps it should not. Loving Portrait of Jennie is an imperfect experience, but just as Jennie accepts her fate for a few cherished moments with Eben, so too does the viewer revere the film’s many pleasures.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Julian!)

Bibliography:

Behlmer, Rudy, editor. Memo from David O. Selznick. Modern Library, 2000.

Bordwell, David. Reinventing Hollywood. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Bruckner, René Thoreau. “Why Did You Have to Turn on the Machine?”: The Spirals of Time-Travel Romance.” Cinema Journal, vol. 54, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1–23., www.jstor.org/stable/43653089. Accessed 2 June 2020.

Crowther, Bosley. “Selznick’s ‘Portrait of Jennie,’ With Cotten and Jennifer Jones, Opens at Rivoli.” The New York Times. 30 March 1949. https://www.nytimes.com/1949/03/30/archives/review-1-no-title-selznicks-portrait-of-jennie-with-cotten-and.html. Accessed 1 June 2020.

Freud, Sigmund. “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming.” The Freud Reader. W. W. Norton & Company, 1995, pp. 436-442.

Thomson, David. Showman: The Life of David O. Selznick. Abacus, 1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review