The Definitives

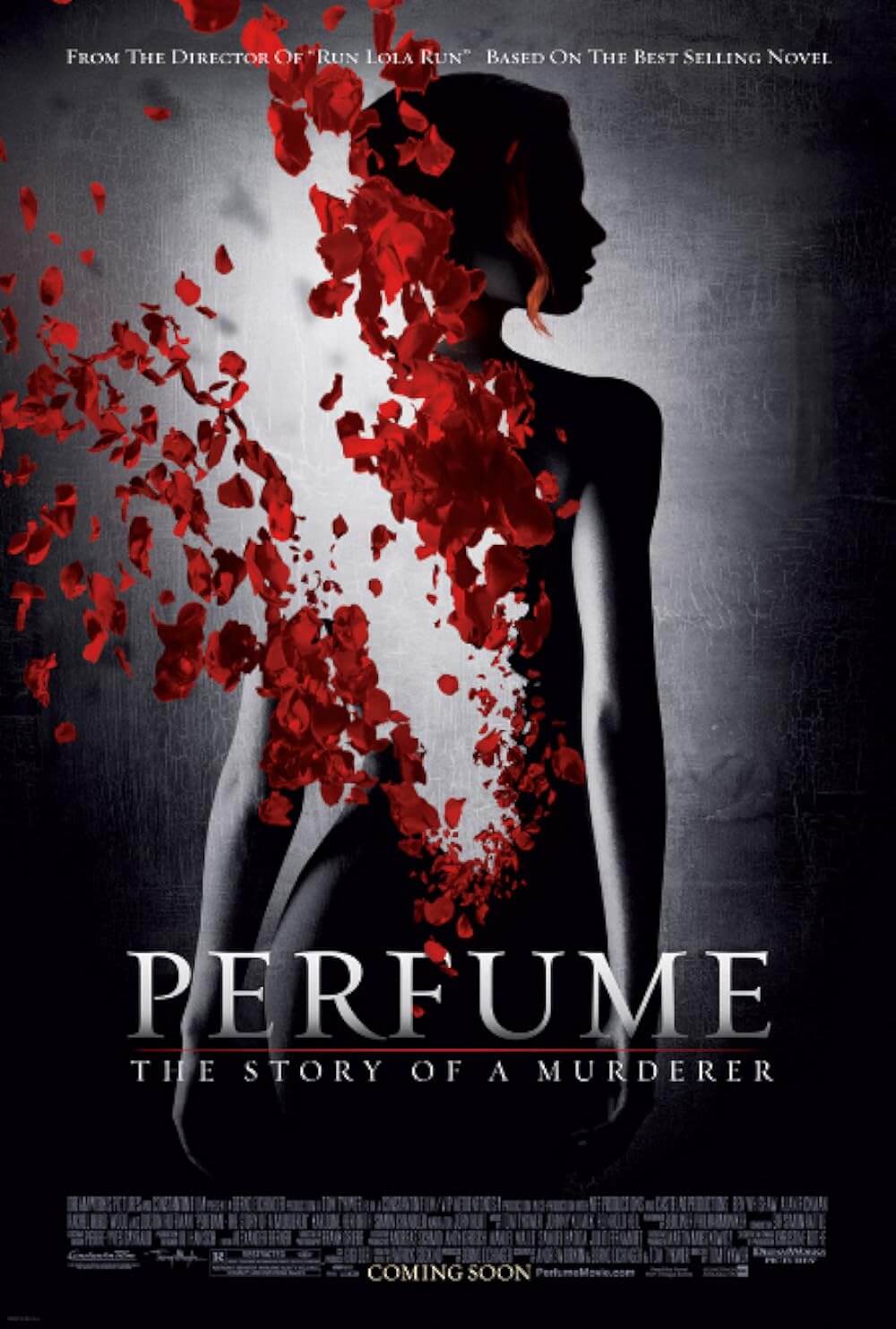

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Born into a world of scents that today are unimaginable, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille enters this life when his mother delivers him from her womb onto the pile of refuse under her fish cart in the middle of a Parisian marketplace. She leaves him for dead, assuming he will turn out like her previous four failed births. The year is 1738, and the unwritten rule before modern views on public health, sewers, and waste management, is that the larger the city, the stronger the smell. Every horrible marketplace odor, from the stench of animal entrails to fresh vomit, awaken the baby from his birthed slumber. The smells give him life, and until his death, smells will guide his very existence. The baby cries his first breaths, and his sound alerts the crowd to his mother’s crime of abandonment, for which she receives a sentence of execution. She will be one of Jean-Baptiste’s many former caretakers in life who he leaves behind to a grim fate. And from that moment onward, Jean-Baptiste relies on his enhanced olfactory senses in the way most of us rely on sight or the way a sharp sense of hearing compensates the blind. It will be his passion, his craft, and, along with his possessed desire to recapture the scent of a woman, it will be an obsession that will incite him to homicide. Such powerful smells, though rare for the cinematic medium, will also be the driving force behind Perfume: The Story of a Murderer.

Based on Patrick Süskind’s so-called “unfilmable” novel Perfume from 1985, German director Tom Tykwer’s adaptation balances several concurrent yet oppositional themes and attitudes. Part of his film revels in ecstasy over visual and olfactory experiences, no matter if they are sensuous or sometimes repellent. Like its protagonist at first, Tykwer does not discriminate between the beautiful and the ugly; to savor a raw experience, pleasant or not, is essential. The participation itself is fundamental. Another part of the film harnesses macabre subject matter, which involves Jean-Baptiste’s horrific killings of several young women to complete an omnibus of female scents. Still another aspect of Tykwer’s film engrosses the viewer in the grimy-yet-gorgeous contrasts present in eighteenth-century Paris, represented with incredible detail. Underneath these concurrent elements, Tykwer muses on the transportive effect of smells, how they ingrain themselves into our unconscious mind, and link with our memories, desires, history, and identity. A final aspect of the film, which, more than the others mentioned so far, sets it apart from what is otherwise a historical story about a perfuming killer, is how this narrative transforms into a kind of fairy tale, or something closer to legend. This last element imprints itself in our minds like an unforgettable scent from long ago.

Though released in 2006, the production had been developed for many years prior, with Süskind hesitant to release the film rights to his book unless a master director like Stanley Kubrick or Milos Forman agreed to apply their perfectionist-level talent to the adaptation. Kubrick even considered it, but ultimately determined it was an impossible, unfilmable text. Süskind was eventually convinced to sell the rights in 2000 to producer Bernd Eichinger, purportedly for $10 million from the producer’s own accounts. After meeting with several directors, only Tykwer stood out to Eichinger, as he had demonstrated both his practical sense and visionary audacity—both certainly required for the proposed adaptation—on his previous work. Run Lola Run (1998) was a fast-paced yet philosophical exploration of a brief series of events, all replayed and rethought with the energy of music video. With Heaven (2002), he completed the first in a planned trilogy left incomplete by the death of its screenwriter and intended director, Krzysztof Kieslowski. Tykwer told London’s The Independent that he was never interested in period pieces, because “They have this tendency to show a period as if it’s something that wasn’t really alive… It’s always about showing off costume design and art direction and stuff, like they’re saying: ‘Look, we’ve collected all these original items from some period,’ and I, as the audience, totally don’t care a bit.” But then Tykwer realized that the story itself would dare its audience to care, and he signed to direct.

Though released in 2006, the production had been developed for many years prior, with Süskind hesitant to release the film rights to his book unless a master director like Stanley Kubrick or Milos Forman agreed to apply their perfectionist-level talent to the adaptation. Kubrick even considered it, but ultimately determined it was an impossible, unfilmable text. Süskind was eventually convinced to sell the rights in 2000 to producer Bernd Eichinger, purportedly for $10 million from the producer’s own accounts. After meeting with several directors, only Tykwer stood out to Eichinger, as he had demonstrated both his practical sense and visionary audacity—both certainly required for the proposed adaptation—on his previous work. Run Lola Run (1998) was a fast-paced yet philosophical exploration of a brief series of events, all replayed and rethought with the energy of music video. With Heaven (2002), he completed the first in a planned trilogy left incomplete by the death of its screenwriter and intended director, Krzysztof Kieslowski. Tykwer told London’s The Independent that he was never interested in period pieces, because “They have this tendency to show a period as if it’s something that wasn’t really alive… It’s always about showing off costume design and art direction and stuff, like they’re saying: ‘Look, we’ve collected all these original items from some period,’ and I, as the audience, totally don’t care a bit.” But then Tykwer realized that the story itself would dare its audience to care, and he signed to direct.

Given Tykwer’s initial reservations and eventual reason for signing on, Süskind’s preliminary desire to secure Kubrick as a director could not have been more appropriate. In films such as A Clockwork Orange (1971) and especially Barry Lyndon (1975), Kubrick had explored subjects that, along with his rigid formality, defied audiences to find their redeeming qualities and experience empathy. Tykwer was presented with the same problem and assisted Eichinger and Andrew Birkin (who had written Eichinger’s production of The Name of the Rose in 1986) in adapting Süskind’s novel, in which its protagonist, Jean-Baptiste, barely speaks. Their solution was to transform some of Süskind’s prose into the voice of a narrator, read in the film by John Hurt’s gravelly voice. This crucial addition, particularly in the film’s first half, welcomes us into the story’s decrepit eighteenth-century world. In a true novelistic fashion, the voiceover recounts the fates of characters that no longer share scenes with Jean-Baptiste. As for our demented hero, the narrator describes him as being “tough as a resilient bacterium” at one point. Süskind’s prose, and thus the narrator’s commentary, becomes a shaping mechanism for our view of the story. And what the narrator cannot tell us, Tykwer shows us by submerging his audience in sensory detail—visual, aural, and through the combination of the two—to create a sense of the olfactory impressions that remain central to the film, both narratively and thematically.

Financed with $60 million from a cadre of European investors, Eichinger and Tykwer’s film commenced shooting on July 12, 2005, and concluded on October 16 of that year. And while it would only make $2 million in the United States, the production earned $135 million in worldwide box-office receipts, with $53 million in Germany alone, despite being a German production of an English-language film set in France. Some critics, such as Roger Ebert, championed Perfume, but the majority of reviews were lukewarm, if not negative. More than one critic called it “hollow” or “a vacuum,” and many found the film’s blending of murder, artistic ambition, and unconventional existentialism unsettling beyond redemption. But as Ebert would point out, a “brave curiosity” is required from the film’s audience, not only to understand Jean-Baptiste’s unusual predilections but to find some common ground with the character. A common thread in our ability to relate to one another rests in how we pursue love, happiness, and approval. For Jean-Baptiste, he understands only scents and, through them, achieves fulfillment. Tykwer observed, “I could feel some deep understanding, not only sympathy but something more complex as an emotion, with this guy… and this system that he establishes for his pursuit of happiness.” To be sure, our capacity for human understanding is pushed to its limits here, reaching heights not achieved outside of Kubrickian cinema. And though at first we may be repulsed by Jean-Baptiste, upon revisiting the film, his story becomes hypnotic, haunting, and strangely affecting.

In the first moments of Perfume, Jean-Baptiste (Ben Wishaw, who at once hones the protagonist’s innocent, obsessive, and monstrous tenors) appears in shackles, while a crowd outside clamors for his death sentence. In the next moment, the narrator will take us through the character’s birth and upbringing, and his uncanny sense of smell. At the same time, others find him strange, different, and often unnerving. The children in his orphanage, sensing something is very wrong about the boy, try to smother him. Though he cannot talk yet by the age of 5, Jean-Baptiste sees with his olfactory sense, closing his eyes and charting the world around him by visualizing what the smells tell him. Scents also serve as a kind of radar. He dodges a rotten apple thrown at him by a fellow orphan when he smells it coming. But even so young, he already seems predestined to become a perfumer; he combines the scents of a fallen twig, leaf, and apple, and he equates them to a nearby apple tree. After some time passes and he’s too old to be an orphan, he’s sold to a tannery for 7 francs. Under punishing conditions, Jean-Baptiste survives where few could, though his existence is hardly a life. Not until he’s grown up and allowed on his first trip to deliver skins in downtown Paris does Jean-Baptiste awaken to the beautiful world of scents that had long eluded him—spices; horses; wig powder; fresh fruit; the predominance of perfumes in the crowded, often wretched city; and above all, the scent of women.

While wandering the streets on his first night in Paris, Jean-Baptiste sniffs out a red-headed peasant girl (Karoline Herfurth) carrying a basket of ripe plums. She is stunning, but her scent is what attracts Jean-Baptiste. He follows her through the crowd. Eventually, she notices him, greets him, and offers him a plum. Rather than take it, he buries his nose into her hand, greedy for her scent. She runs away, afraid of his strange behavior. Later that night, he finds her again. She screams, and he covers her mouth so others cannot hear, but at the same time, she cannot breathe. He does this not in a conscious decision to kill, but as a result of his greed for her scent, he wants it all for himself. What he soon finds while inhaling the scent of her corpse is that her smell—the location of what is later described as “the soul of being”—quickly dissipates after death. Now Jean-Baptiste’s mission in life becomes clear: he must find a way to preserve scent, to preserve beauty, and keep it for himself forever. Because of his strange entrance into this world, because of his upbringing or lack thereof, because the poor wretch never learned anything about love and relied only on the impulse of his senses to guide him, his solution is to capture and maintain love and infatuation in the form of scent, of perfume.

Enter Giuseppe Baldini (Dustin Hoffman), a washed-up Italian perfumer living on the Pont au Change bridge, where he keeps a fragrance shop so saturated in strong aromas that customers dare not enter. Delivering goat hides, Jean-Baptiste enters Baldini’s workshop as though he has worked there for years. He demonstrates how his nose is so skilled that, though he cannot read, he can identify the scents of essential oils, even through sealed bottles. In exchange for Jean-Baptiste’s skill and almost whimsical ability to concoct spontaneous, elaborate perfumes that will revitalize Baldini’s shop, Baldini agrees to teach Jean-Baptiste the art and craft of perfuming. Here the audience learns a crash course in perfuming by way of musical terminology: A perfume’s formula is comprised of three separate notes, and each note contains four individual scents. When the notes are combined, they ring out in harmony, or accord. Each perfume begins with a light Head Note, which delivers the first impression and quickly dissipates; next comes the Heart Note, sometimes lasting for hours; and the final Base Note might last for days. But Baldini tells Jean-Baptiste that many perfumers believe a thirteenth scent is required for a truly great perfume. He tells a story about such a perfume that was discovered when an ancient Egyptian tomb was opened; it released a fragrance so wondrous that, for a moment, everyone on Earth believed they were in paradise.

In Jean-Baptiste’s time with Baldini, he learns the process of distillation, where ten-thousand roses equate to one ounce of essential oil. The film draws us into this world of scents and cultivates our fascination with Baldini and Jean-Baptiste’s techniques, their boilers, alcohol, and concoctions. But a moment comes when Jean-Baptiste realizes he cannot capture some essences—of copper, glass, and an unfortunate feline—and questions how he will ever preserve a woman’s scent. With this, he becomes ill with a psychosomatic case of smallpox and believes his life’s ambition is unattainable. Jean-Baptiste recovers only after Baldini tells Jean-Baptiste about the method of enfleurage, whose secrets may be found in Grasse, the home and origin of the perfuming craft, just off the French Riviera. Leaving Baldini behind with 100 perfume recipes in exchange for a journeyman’s papers, Jean-Baptiste, horribly scarred from his bout of smallpox, travels out of Paris and into the wilderness, where he is freed from the barrage of metropolitan scents. In the wild, he finds shelter in an almost scentless, ancient cave, far away from his sensory-inspired obsession. There, he realizes that he has no odor of his own. By his own understanding, without a scent, he has no existence. He is nothing. And to show himself, and indeed the world, that he is something—an exceptional, incomparable talent—he vows to create the perfect perfume. It is an existential crisis completely unique to cinema.

In Jean-Baptiste’s time with Baldini, he learns the process of distillation, where ten-thousand roses equate to one ounce of essential oil. The film draws us into this world of scents and cultivates our fascination with Baldini and Jean-Baptiste’s techniques, their boilers, alcohol, and concoctions. But a moment comes when Jean-Baptiste realizes he cannot capture some essences—of copper, glass, and an unfortunate feline—and questions how he will ever preserve a woman’s scent. With this, he becomes ill with a psychosomatic case of smallpox and believes his life’s ambition is unattainable. Jean-Baptiste recovers only after Baldini tells Jean-Baptiste about the method of enfleurage, whose secrets may be found in Grasse, the home and origin of the perfuming craft, just off the French Riviera. Leaving Baldini behind with 100 perfume recipes in exchange for a journeyman’s papers, Jean-Baptiste, horribly scarred from his bout of smallpox, travels out of Paris and into the wilderness, where he is freed from the barrage of metropolitan scents. In the wild, he finds shelter in an almost scentless, ancient cave, far away from his sensory-inspired obsession. There, he realizes that he has no odor of his own. By his own understanding, without a scent, he has no existence. He is nothing. And to show himself, and indeed the world, that he is something—an exceptional, incomparable talent—he vows to create the perfect perfume. It is an existential crisis completely unique to cinema.

Throughout Perfume, Tykwer’s imagery engages our sense of smell in the same way scent can sometimes bring about memory. He accomplishes this, in part, with Uli Hanisch’s exceptional production design in recreating eighteenth-century Paris. After all, no city in history was written about more for having contained such a diversity of foul odors, sometimes masked with the most pleasant perfumes ever created. With the emergence of the modern city, smells both delightful and repugnant resulted from overpopulation and industry. They perforated Paris, a city whose stink would be unbearable today. In his book The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs, author David S. Barnes wrote about the smells of Paris that had been associated with the city for centuries. Barnes described a “daunting volume of all organic matter produced, consumed and excreted by nearly a million Parisians—uneaten foodstuffs, animal hides, carcasses, dung, all human body fluids and solids.” Not until a century later, when public outcry demanded a response to the stink, would the city begin a civilizing process that updated its sanitation methods and alleviated the otherwise intrusive smells. Like the film’s narrative, the director’s formal approach immerses us into, as the narrator calls it, “the fleeting realm of scent,” by shooting in hyper-realized detail and close-ups. Cinematographer Frank Griebe shot on a Kenworthy/Nettman Snorkel Lens System to get uncommonly close to the film’s characters, next to Jean-Baptiste and Baldini’s noses, next to a droplet of essential oil, next to squirming maggots, next to fruit, and next to bottled aromas whose beauty can only be imagined. It’s an odd experience for any viewer. But somehow, Tykwer evokes these scents, even if they exist only in our minds. Tykwer argued, “A book doesn’t smell either, it’s all language; and film is also language.”

Because we are so invested in the smells of the film, Jean-Baptiste’s planned perfume comes with a strange sense of anticipation. Once in Grasse, he begins with no intention of becoming a killer; rather, he engages a prostitute to take part in the enfleurage technique, which he has learned after becoming an assistant in the local industry. To extract scent in this method, he spreads animal fat onto the subject, wraps her in cloth, strains the grease from the fabric,s and mixes it with alcohol, which is then evaporated, leaving only the extracted scent in a pure form. But Jean-Baptiste’s prostitute refuses to take part, and so he clubs her, then through enfleurage, discovers he can finally capture a woman’s scent in perfume. More than that, he realizes the scent can lure the prostitute’s dog, even bewilder men. He continues to form his accord, and so Grasse is met with a string of murders that incites panic. Local magnate Antoine Richis (Alan Rickman), desperate to protect his innocent daughter Laura (Rachel Hurd-Wood) from the killer, launches a curfew and manhunt, neither of which prevent Jean-Baptiste from finding twelve women to construct his perfume. Each victim is found clubbed dead, stripped, their hair chopped (and strained for its essence), but not violated sexually in any way. Though he does not know why Antoine believes the killer wants his daughter, and with his daughter in tow, he tries to flee from Grasse in secret to protect her. Jean-Baptiste uses his nose as his guide and easily finds the Richis family in hiding. He takes his final, thirteenth element for his perfume with Laura’s death. Just moments after he combines his scents into a truly great perfume, Jean-Baptiste is captured.

Before he ever made a conscious decision to kill, Jean-Baptiste had been surrounded by death. His mother is hung for child abandonment after his newborn cries alert bystanders to her crime; the former mistress of his orphanage finds her throat slit within moments of selling Jean-Baptiste to a tannery; the chief tanner, drunk on his fee from Baldini, falls and drowns in the river; and Baldini never uses any of the 100 recipes that Jean-Baptiste writes him because his spot on the Pont au Change collapses just after Jean-Baptiste leaves for Grasse. With his body count, both intentional and unintentional, reaching nearly twenty, the audience must question how they can empathize with a serial killer. This is not an easy question to answer, and it’s the primary factor distancing many from the film. After all, Jean-Baptiste maintains a method of killing that is just as meticulous as any number of serial killers in contemporary media and pop-culture. But his meticulousness is also just as exacting as Baldini’s perfuming technique. So Tykwer leaves it to the viewer to determine how we judge Jean-Baptiste: as a killer, or as an artist in the midst of exploring his passion for creating. Tykwer resists the temptation to give us the answer. Certainly, it could never be so polarized. Jean-Baptiste is a killer and, unmistakably, an artist; but he is also someone trying to figure out how to love. To ignore these opposing ideas is to completely miss the beauty, intertextuality, and metaphor contained in Perfume.

Before he ever made a conscious decision to kill, Jean-Baptiste had been surrounded by death. His mother is hung for child abandonment after his newborn cries alert bystanders to her crime; the former mistress of his orphanage finds her throat slit within moments of selling Jean-Baptiste to a tannery; the chief tanner, drunk on his fee from Baldini, falls and drowns in the river; and Baldini never uses any of the 100 recipes that Jean-Baptiste writes him because his spot on the Pont au Change collapses just after Jean-Baptiste leaves for Grasse. With his body count, both intentional and unintentional, reaching nearly twenty, the audience must question how they can empathize with a serial killer. This is not an easy question to answer, and it’s the primary factor distancing many from the film. After all, Jean-Baptiste maintains a method of killing that is just as meticulous as any number of serial killers in contemporary media and pop-culture. But his meticulousness is also just as exacting as Baldini’s perfuming technique. So Tykwer leaves it to the viewer to determine how we judge Jean-Baptiste: as a killer, or as an artist in the midst of exploring his passion for creating. Tykwer resists the temptation to give us the answer. Certainly, it could never be so polarized. Jean-Baptiste is a killer and, unmistakably, an artist; but he is also someone trying to figure out how to love. To ignore these opposing ideas is to completely miss the beauty, intertextuality, and metaphor contained in Perfume.

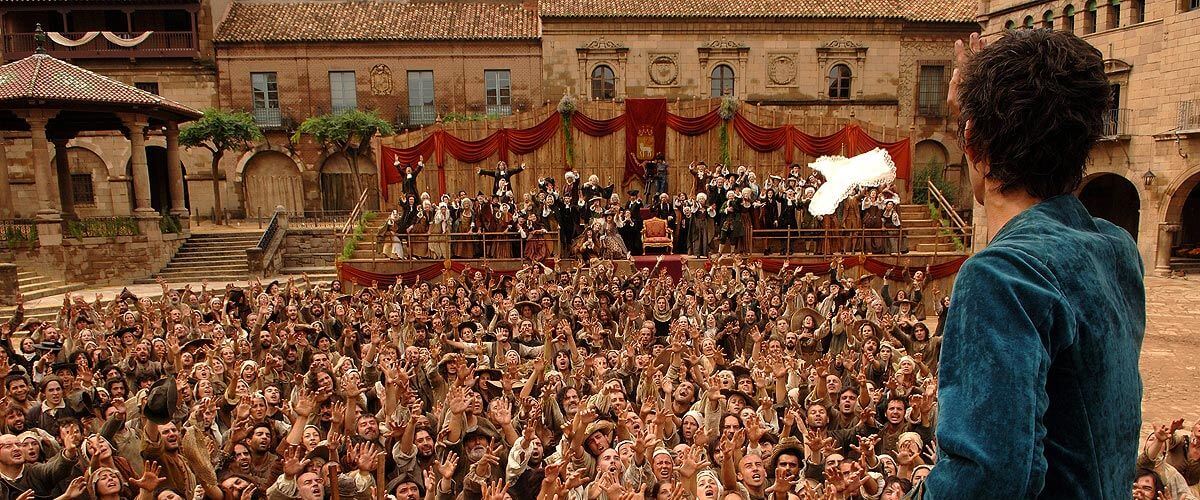

And since the crowd (in this case, the film’s audience) has such a decisive role in determining how to judge Jean-Baptiste, we must look at Tykwer’s most fascinating treatment of crowds—that irrepressible force pulsating through this period of history, especially in France. Shortly after the events in Perfume, crowds arose to bring about The Terror, one of the most rage-fuelled periods in history, incited by the French Revolution. In each case within the film, the crowd serves as an unruly and unreasonable force, a populace of which Jean-Baptiste is not a member, yet from which he seeks approval and cares greatly to please with his scents. The crowd in the first scene clamors for Jean-Baptiste’s execution and cheers at his sentencing. In another early scene, when Jean-Baptiste first arrives in Paris, the crowds flow like schools of fish. In Grasse, a mob converges in the church for a local Bishop to excommunicate the killer from their town; when news comes that someone has confessed to Jean-Baptiste’s murders, the crowd cries out with a revelatory chant, “Amen!” and the town’s mob mentality wanes. At Jean-Baptiste’s execution, the masked executioner incites the vast crowd that is so hungry to see a display of gristly justice. These moments anticipate the film’s most famous crowd scenes, which arrive in the last strange, intoxicating, and most fairy tale-esque sequences in the film.

Just when he should be moved for execution, Jean-Baptiste dabs himself with his truly great perfume and entrances his prison guards. Instead of in chains, they escort him by carriage out to the square, where the bloodthirsty horde quiets at his appearance and, most importantly, his smell. Now dressed in formal wear, Jean-Baptiste approaches the executioner’s stage, and the executioner falls to his knees at Jean-Baptiste’s scent and proclaims him innocent. Jean-Baptiste responds by wetting a handkerchief and waving it over the crowds; then, he gives a bow. Everyone fawns. The Bishop in attendance declares, “This is no man. This is an angel!” Cheers and crying over his beautiful innocence overcome the crowd, even Richis. All at once, everyone falls into rapturous desire, disrobes, and loses themselves in sexual delight. The swarming, angry mob transforms into a throng of naked flesh consumed by sensory bliss. But at this, Jean-Baptiste can think only of his plum girl and how he will never be loved like a normal person. The orgiastic crowd eventually awakens from their enchantment and departs from the scene, never to speak of what happened. Though he could use his perfume to command the love of humanity, to control the world, he resolves instead to return to his place of birth, to the Paris fish market. He pours the remaining perfume over his head. The local merchants and buyers look on to see an angel, and they are compelled to flock to Jean-Baptiste and devour him, eating his flesh until nothing remains. In doing this, they feel they have done something “purely out of love.”

At its most complex, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer becomes an existential fable, as Jean-Baptiste realizes something on par with Baldini’s tale of an ancient Egyptian scent—and therein, the narrative is less about a historical period or the craft of perfuming than a strange legend to be passed down for the ages, wherein the lesson is that love is relative. At its simplest, Perfume is a dark allegory for what poets have described as our necessity to recapture the purity of our first true love. In either case, Tykwer’s engrossing film challenges our senses and emotions. He places before us a wellspring of visual stimuli rooted in the awesome oppositional powers of repugnance and splendor. Through them, he makes a connection between our vision and olfactory senses the way few motion pictures have (it might be the only film in history that could justify the existence of Smell-O-Vision). Tykwer also defies us to empathize with Jean-Baptiste, whose status as a murderer, at least within the context of the film’s themes and drama, is less significant than his desire to love and be loved. Whimsical, disgusting, beautiful, disturbing, and evocative, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer conjures all manner of responses, and itself serves as a kind of cinematic accord, whereby layers reveal themselves over time and result in a sensory experience unlike any other.

At its most complex, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer becomes an existential fable, as Jean-Baptiste realizes something on par with Baldini’s tale of an ancient Egyptian scent—and therein, the narrative is less about a historical period or the craft of perfuming than a strange legend to be passed down for the ages, wherein the lesson is that love is relative. At its simplest, Perfume is a dark allegory for what poets have described as our necessity to recapture the purity of our first true love. In either case, Tykwer’s engrossing film challenges our senses and emotions. He places before us a wellspring of visual stimuli rooted in the awesome oppositional powers of repugnance and splendor. Through them, he makes a connection between our vision and olfactory senses the way few motion pictures have (it might be the only film in history that could justify the existence of Smell-O-Vision). Tykwer also defies us to empathize with Jean-Baptiste, whose status as a murderer, at least within the context of the film’s themes and drama, is less significant than his desire to love and be loved. Whimsical, disgusting, beautiful, disturbing, and evocative, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer conjures all manner of responses, and itself serves as a kind of cinematic accord, whereby layers reveal themselves over time and result in a sensory experience unlike any other.

Bibliography:

Barnes, David S. The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Süskind, Patrick. Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. Penguin Books, Ltd., 1995.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review