The Definitives

Paths of Glory

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Three French soldiers of The Great War brood in a makeshift cell. Their execution is scheduled for dawn. Cold walls surround them, offering no solace. One of them, Private Arnaud (Joe Turkel), curls up on the floor in despair. Another, Corporal Paris (Ralph Meeker), waxes philosophical: “See that cockroach,” he says. “Tomorrow morning, we’ll be dead, and it’ll be alive. It’ll have more contact with my wife and child than I will. I’ll be nothing, and it’ll be alive.” The third soldier, Private Ferol (Timothy Carey), slaps his hand down and crushes the insect, “Now you got the edge on him.” The biting cruelty of military logic has labeled these three random soldiers guilty of a crime and placed them in an overnight death row. However, they were chosen at random to represent their companies for alleged cowardice on the battlefield, as opposed to an individual criminal deed. They are nothing more than pawns in a game of military politics. Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, the director’s most humanist work, is not only an antiwar film but also a depiction of the horrors of bureaucratic military hierarchies, overseen by corrupt officials. Kubrick’s 1957 film takes on the power-mongering and inequality on the military social ladder, exposing its abuses of honor and justice.

Based on Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel, Paths of Glory is the second Kubrick film derived from a novel; every subsequent film made by the director would adapt a piece of literature to the screen. Cobb based the book on actual events, first reported in The New York Times in 1915, where the French military command ordered a division to sacrifice itself in an attempt to overtake an impenetrable stronghold called The Pimple. When the attack inevitably failed, five soldiers were selected at random, court-martialed, and executed to restore France’s honor and shield the command from responsibility for the mission’s failure. The soldiers were acquitted of their so-called crimes two decades later. Cobb took the title from Thomas Gray’s poem, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” which reads: “The paths of glory lead but to the grave.” Kubrick had read the book as a teenager and remembered the text fondly for its realistic account of war, though it’s unclear if he saw Sidney Howard’s stage adaptation during its short-lived run on Broadway in 1935.

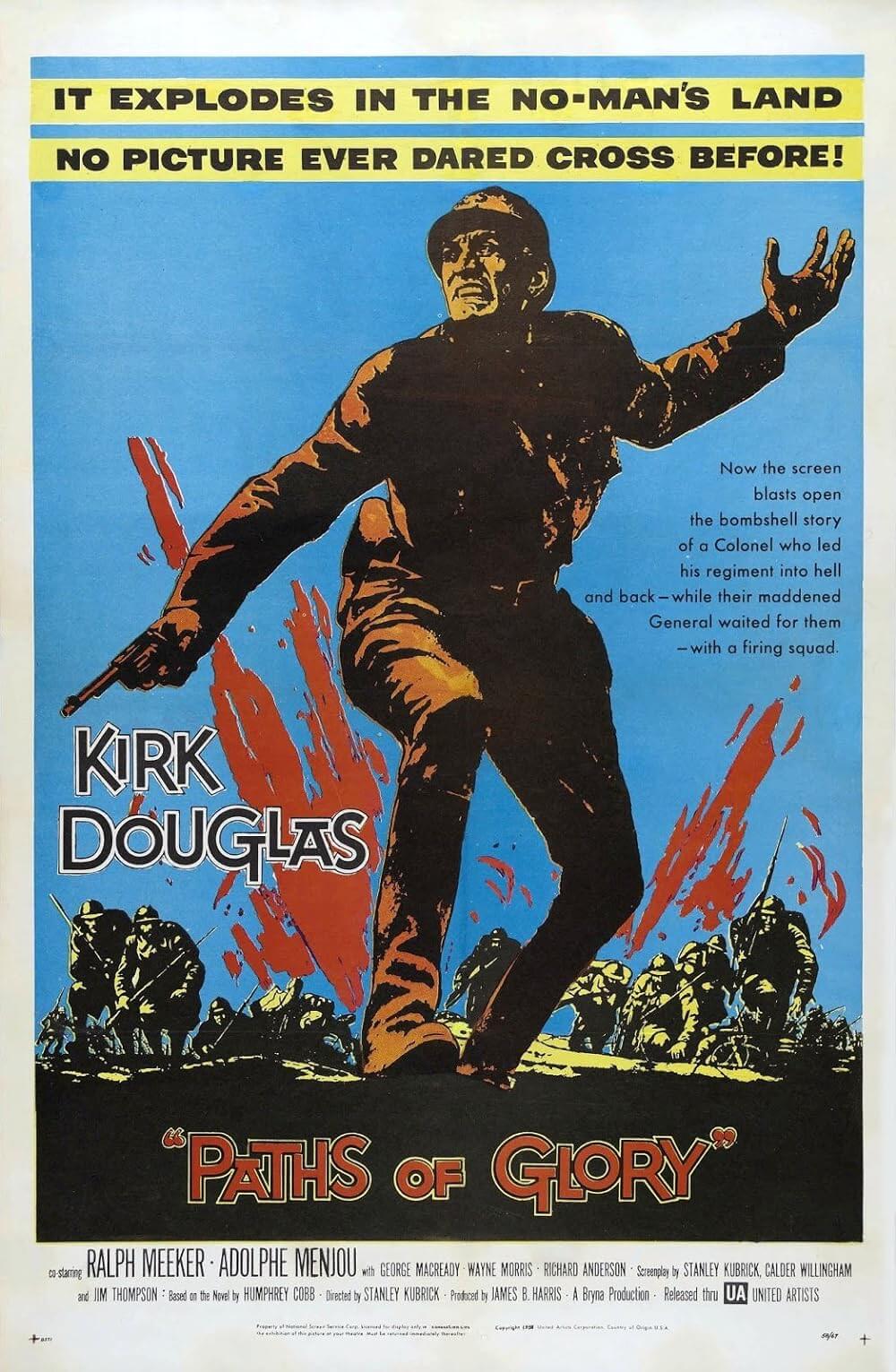

When searching for his next project in 1956, Kubrick was reminded of Paths of Glory by his producing partner James B. Harris, and they settled on Cobb’s book as their next project. After the director wrote the screenplay alongside Jim Thompson and Calder Willingham, they shopped the material around Hollywood to almost universal rejection. The project didn’t take off until Kirk Douglas, who shared an agent with the writers, saw Kubrick’s most recent film, The Killing (1956), and wanted a meeting with the filmmaker, still in his twenties. Kubrick and Harris signed a deal with Douglas’ Bryna Productions that made Paths of Glory the first of a proposed four-picture deal, which Kubrick and Harris would almost immediately regret, given the lack of control the agreement afforded them. However, the deal meant the budget was Bryna’s problem, and the company struggled to secure financing at first. World War I was not considered a commercially viable war in cinema, and worse, the book proved unpopular in international territories. United Artists ultimately agreed to release the film, which Kubrick shot in Germany—the French refused to allow the production to shoot there—to take advantage of lower costs and less interference.

The setting is the French-German conflict near the end of the First World War—a war not bound by the moral struggles of good and evil in comparison to the Second World War, but set afire largely by an unfavorable mix of distrust, unruly demands, strained alliances, and jumping the gun, so to speak. Though often described as the first “Great” war, what remains are soldiers blindly dying in some of history’s bloodiest battles over disputes best remembered for setting up the successive (and more decisive) conflict. Often considered the most pointless of wars in the modern era, cinema has used World War I to comment on how war is a political tool, leaving fields of corpses in its wake. Such is the case with All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Lewis Milestone’s Oscar-winning adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel. It earns comparisons to Paths of Glory: both American films unfold from the perspective of European countries, Germany in Milestone’s film, France in Kubrick; both feature harrowing battlefield scenes; both weigh the reasoning of military command, which coldly exploits soldiers for its own purposes, against the staggering loss of human life.

Untenable from a humanist perspective, the First World War affords Kubrick a backdrop ripe with hypocrisy and class struggles: the stuff of grand drama. The film involves the engineered execution of three soldiers as political whipping boys for an official determined to make an example out of them in an act of strategic self-preservation, not to mention a name for himself. Decimation, as it is known, goes back to pre-Roman times and involves the military command executing members of its army to demonstrate why the others should follow orders. The French used it during the First World War to promote good behavior, order, and a sort of forced bravery among the ranks. Kubrick uses decimation as the dehumanizing apparatus employed by bureaucrats—an order that singularly does away with a soldier’s individuality by reducing him to a number and removing his humanity, and then placing him before a firing squad.

The film’s French officers assemble not in a rugged barracks but rather a refined chateau, seized to house generals with too much power and little more than moral ambivalence about war. Indeed, Kubrick’s choice of location for military command—in the partly bombed-out Schleissheim castle, since converted to a national museum in a Munich suburb—suggests the film’s underlying social conflict. Gaudy, and somehow seedy despite its shine, the posh chateau features massive paintings, baroque ornamentation, and lavish furnishing—an ironic and absurd locale for men planning a war, yet wholly representative of the class conflict driving Paths of Glory. As the film progresses, cinematic battles between the French and German combatants, however expertly photographed by Kubrick and cinematographer Georg Krause, become secondary to the warring classes within the French chain of command—in particular, the humanism of grunt soldiers, whose barracks are no more luxurious than a hole in the ground, versus the promotion-obsessed command staff, led by men who spend their evenings hosting formal parties and who wield officialdom in service of vanity and self-preservation.

These men include Major General Broulard and his subordinate, Brigadier General Mireau. The latter is played by George Macready, who appeared opposite Douglas in William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951). Adolphe Menjou plays the former, his once-pristine reputation since tarnished by testifying to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and naming names of Hollywood communists—an extratextual allusion that Kubrick may have used to sow a feeling of mistrust in Menjou’s character. The film’s first scenes render a defining exchange between the two: Broulard commands Mireau to send his division to overtake The Ant Hill—an impossible mission. Mireau objects, citing the likelihood of vast casualties and a small probability of victory. Then Broulard mentions the possibility of Mireau’s advancement with another general’s star; suddenly, Mireau insists the odds of success are not so small. On the turnaround, when Mireau instructs Colonel Dax (played by the square-jawed Kirk Douglas in his fiercest role) to plan the assault, Dax makes the same objections, which Mireau dismisses, despite his initial reservations with Broulard.

On the battlefield, trench warfare has scarred the landscape into mounds and troughs cut by opposing sides. Nameless soldiers tear through mud and debris, dodging bullets and exploding mortars. The terror of war depicted by Kubrick is staggering. Dax leads Company A onto the field where enemy fire tears them down; seeing this, Company B remains behind, disobeying orders. General Mireau, observing from a safe distance, enraged and frustrated since another star hangs in the balance, orders artillery to open fire on the French line—to motivate them out of the trenches or destroy them for their cowardice. The battery commander refuses unless he has the disturbing order in writing. Mireau insists, and his orders are once again refused, and so he determines to execute the men for lack of courage. Self-satisfied in his outrage, he resolves to bring about a court-martial, proclaiming, “If the little sweethearts won’t face German bullets, they’ll face French ones!” It’s a line that exposes Mireau’s empty sentiments in the first scenes when he announces, “The life of one of those soldiers means more to me than all the stars and decorations and honors in France.”

Paths of Glory portrays the arithmetic of human lives as a power-brokering device employed by ambitious officials; after all, with the soldiers’ refusal to charge, they placed Mireau’s promotion at risk. In a subsequent meeting between Broulard, Mireau, and Dax, the three discuss the pending court-martial and the number of men to be charged. Insisting the mission was impossible, Dax supports his men. “If it was impossible,” Mireau says flatly, “the only proof of that would be their dead bodies lying on the bottom of the trenches.” To satisfy his performative outrage, Mireau demands the lives of ten men from each company, a hundred in all. Dax wonders why so many, and offers himself instead, having led the alleged cowards. This is not a question of officers but grunts, Broulard insists, and he recommends a dozen men. Mireau concedes with a counter-bid of three, drawn at random by each company’s commander. The entire conversation feels negotiated by car salesmen, save for Dax’s attempt at self-sacrifice.

The selection process occurs offscreen. Lieutenant Roget (Wayne Morris), a coward desperate to save his hide, strategically picks Corporal Paris, who threatens to expose Roget’s cowardice and incompetence. The night before the assault on The Ant Hill, the half-soused Roget leads a scouting mission with two other men, including Paris. He sends the other soldier to scout ahead, and when the soldier doesn’t return, Roget panics and tosses a grenade that kills the scout. Paris is the only witness to this, and not even informing Dax of Roget’s crime can save him from the execution. Private Ferol is selected because his commander deems him a “social undesirable,” a quality reflected in Carey’s darkened, slow-blinking eyes and off-kilter mannerisms. Still, the most maddening selection is Private Arnaud, whose company drew lots—a comment on the senselessness of military reasoning. It’s not until the execution, when Roget offers each of the condemned men a blindfold, that he, ashamed, unable to raise his downcast eyes, apologizes to Paris. “I’m sorry,” he says quietly. Paris nods, almost annoyed; tied to a post in front of a firing squad, Roget’s conscience is the last thing on Paris’ mind.

Kubrick’s camera makes calculated and elaborate movements that earned his work comparisons to Max Ophüls, one of Kubrick’s favorite directors. More than any other Kubrick film before or after, Paths of Glory has a strict architecture that emphasizes its conceptual purpose—that military command decides the fate of human beings based on warped logic. Defending his men, Dax, an attorney before he enlisted, finds the military court dishonest, calculating, and opposed to all evidence, except that which proves the three soldiers guilty. It is a drumhead trial, without a court stenographer or other official aspects. The outcome is a foregone conclusion. Inevitably, the trio of scapegoats will be executed, no matter how well-reasoned Dax’s arguments are. Then Kubrick offers hope: Dax learns of Mireau’s order to open fire on the immobile French line. Surely this crime could lead to the scapegoats’ freedom, or at least demonstrate Mireau’s unsuitability to lead, and therein supply the dramatic 11th Hour device that brings a happy ending. Hoping to stall the execution, Dax brings Mireau’s brash order to Broulard, who, in turn, appears to do nothing approaching the right thing; he intends only to save face for the high command. At the same time, the three sentenced grunts fall apart in their cell. They ignore their last meal of duck sent by Mireau; Ferol believes the food was poisoned. There is no last-minute rescue, no daring race to stop the firing squad’s volley.

Kubrick refuses to pull his greatest punch and give audiences a Hollywood ending. The execution goes off without a hitch. Afterward, General Mireau notes his pleasure with the procession: “The men died wonderfully. There’s always that chance that one of them will do something that will leave everyone with a bad taste, this time you couldn’t ask for better,” he says, biting into a croissant. Uncompromising in his dedication to thematic potency, Kubrick does not deceive the audience into thinking such horrors do not exist, or that soldiers can somehow become more than mere tools for The Powers That Be. Mireau gets his comeuppance, however, when Broulard confronts him with a court-martial for ordering artillery to fire on French soldiers. But this is not a victory, more like a band-aid to treat a heart attack. Even worse, Broulard believes Dax pursued his defense so diligently to secure himself a promotion—he even smiles in disappointment when Dax proves himself a pitiable idealist, earnestly spouting humanist principles. In an earlier scene, Dax quotes Samuel Johnson on patriotism, saying, “It’s the last refuge of a scoundrel.” By the end of the final exchange between Broulard and Dax, we see, at least in this context, how correct Johnson was.

Before initially signing to star, Douglas told Kubrick, “Stanley, I don’t think this picture will ever make a nickel, but we have to make it.” He was right on both accounts. Banned in France until after De Gaulle’s death in 1970, Paths of Glory offended the strong sense of French pride in its military. Several other allied countries sensitive to France’s objections and even U.S. military bases also banned the film. Its diminished worldwide circulation hindered box-office receipts; nevertheless, it was reassessed and recognized for Kubrick’s directorial genius years later. To be sure, Kubrick’s subject matter designates his style on Paths of Glory. His approach includes sharp cutting to reflect the uniform situation; his resourceful treatment of time brings the film’s length to an efficient 87 minutes, whereas Kubrick’s later works are known for their longer runtimes. Each step is precise, filmed with clarity in deep focus. His presentation is unfussy, even geometric, allowing for the form to follow function to tell the best story possible. However, Kubrick’s reputation for sketching out his entire film during pre-production, often after years of meticulous research and planning, is deceptive.

Paths of Glory helped establish Kubrick’s penchant for multiple takes, which has since been alternately mythologized as the tendency of a genius and critiqued as indulgent. The reality is that Kubrick, a lifelong chess player, did not determine every detail in advance; he needed to find what he wanted by having every option available. And like a chess player, he considered all options on the game board. Chess also factors into the court-martial sequence. Kubrick moves his characters on a checkered floor, where the defendants sit opposite the judges like human pieces on a veritable chessboard. His perfectionism stems from a chess player’s intuition for “choice, consequences, and the pattern of play.” After conceptualizing his film, he assembled all formal elements (camera, lighting, script, etc.) around that concept to search for a harmony of style and content. What is more, Paths of Glory remains a shining counterpoint to the director’s critics who would claim that his meticulousness results in films that lack feeling. Here’s a film that overwhelms the viewer with injustice, empathy, and outrage over the hypocrisy and self-interest on display.

Like all Kubrick films, Paths of Glory boasts unparalleled technical mastery. Observe the practical use of the camera in the scenes involving the charge on The Ant Hill and those that preface it. A subjective camera takes Dax’s view as he walks through the trenches, its narrow passages like those in an ant colony. Kubrick widens the size of the actual trench from an accurate four-foot space to six feet, allowing his fluid camera to track Dax down a gauntlet of wary and worn men, whom he soon leads onto the battlefield. Upon frayed terrain, the camera pans left along with soldiers who climb, duck, and fall with enemy fire. Operating the camera himself, Kubrick zooms in on Dax, whistle in mouth, waving his men to continue as they fall by his side, until, all at once, Dax finds himself nearly alone amid the smoke, bodies, and shell-scarred terrain, facing an impossibly long haul before reaching his destination. To capture this chaos, the production detonated literally tons of explosives to recreate No Man’s Land. Kubrick’s extended shots are miraculously regulated and precise, even in their chaos, capturing the hell of trench warfare.

Kubrick’s personal touch, or style, resides in his control. However unfeasible other filmmakers find absolute control when making studio films, Kubrick maintained his independence even while working inside the Hollywood system—his unprecedented contract with Warner Bros. in the 1970s ensured the director’s creative freedom for much of his career. For viewers, his pictures feel like independent productions. Yet, they have studio-grade budgets, resulting in Kubrick’s oeuvre often being the entry point for moviegoers to explore beyond commercial cinema into artistic, foreign, and independent realms. He was a traditionalist who focused on story, even while he experimented with form. The majority of his career was spent isolated in his home in the English countryside, his productions often situated in Europe, far from the meddling of Hollywood executives. Though his films were not independent, Kubrick remained so, operating in solitude to perfect his conceptual processes. His seclusion results in an other-worldliness to his films far removed from his contemporaries or anyone since.

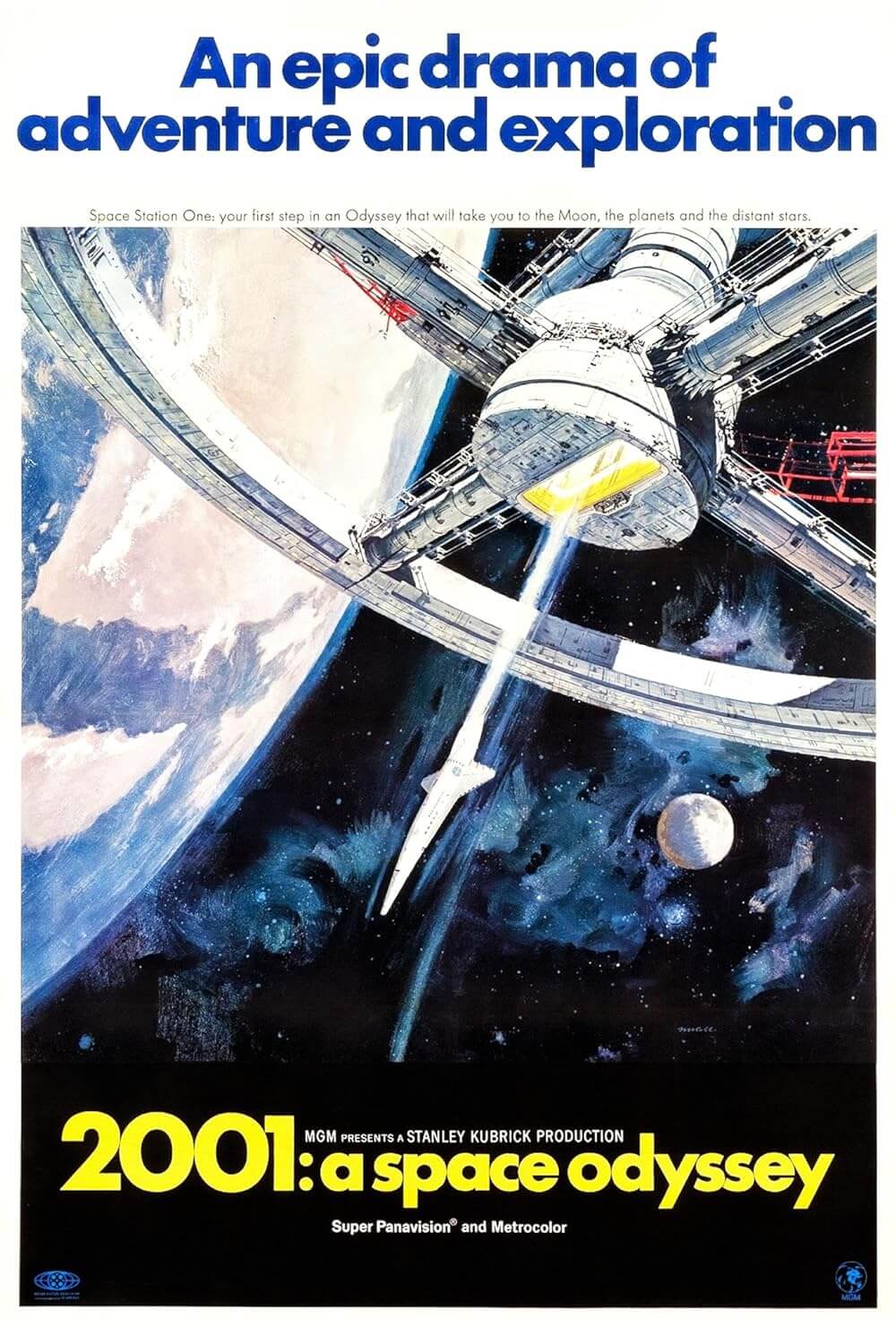

Paths of Glory is sometimes thought of as Kubrick’s first film as a mature filmmaker. Prior to its release, the director had explored style and technique in his debut, the war movie Fear and Desire (1952), followed by two noirish crime pictures, Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing. Although each showed promise in terms of evocative yet documentary-style photography, a focus on action, and, at least in the case of The Killing, a novel approach to narrative structure, none articulated the filmmaker’s voice so well until this, his fourth feature. Kubrick arranges Paths of Glory’s themes, story, and execution to point toward a singular, humanist purpose. It is the same brand of Kubrickian humanism that questions humanity’s absence in Dr. Strangelove (1964) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); the same brand that exposes the failure of social institutions in A Clockwork Orange (1972), which attempt to reform and politicize Alex, an insatiable criminal turned pawn; the same brand of humanism lost in Full Metal Jacket (1987), where Kubrick portrays the dehumanizing effect of boot camp and combat. With Paths of Glory, Kubrick considers how, even among the ranks of soldiers on the same side, conflicts arise—an extension of the omnipresent class struggle that he examines between the soldiers on the ground and those in comparative safety, giving the orders.

Although Gerald Fried’s intense, percussive score exchanges melody and emotion for relentless drumming, Kubrick begins Paths of Glory with the French anthem “La Marseillaise” playing over the opening credits, representing officialdom and patriotism in all its horrible splendor. So it’s an ironic choice that he ends the film with “The Faithful Hussar,” a German folk song. The contrast is as distinct as the battle of songs in Casablanca (1942)—though the juxtaposition is spread across the entire runtime instead of a single scene. The German tune presents a stirring piece of humanism in the face of national anthems or paeans to militaristic glory. The song tells of a young hussar, a cavalry soldier not unlike an adventurous knight, who falls in love with a young woman. Inevitably, he must leave her and go off to war. After a year, he hears news that she has fallen ill, so he rushes home to her, abandoning his position and defying his rank to be with the woman he loves. The song speaks to the importance of connection over duty-bound obedience, of humanity over orders. It is both romantic and tragic, underscoring that the most important type of “faith” is that we give to loved ones, not institutions.

The last scene in Paths of Glory depicts rowdy French soldiers clamoring inside a tavern, hooting at a scared and crying German woman, played by Stanley Kubrick’s future wife, Christiane Harlan. Forced on stage, she quietly sings “The Faithful Hussar,” and her song quells the film’s cynicism with a sobering reprieve. Whereas Broulard asserts, “There are few things more fundamentally encouraging and stimulating than seeing someone else die,” the woman’s song evokes something larger—a reminder to the soldiers that they have families, someone who loves them far outside of the military’s reach. The German woman reminds them of what they left behind: their lovers, wives, and family. Some of the Frenchmen may know the melody, and perhaps even the song’s meaning; they hum along with it, tears streaming down their own faces. Dax watches from outside as his men show empathy for the woman, restoring his faith that some measure of compassion could be left over after the war. For the remainder of his career behind the camera, one gilded by masterpiece after masterpiece, Stanley Kubrick would never again put forward such an emotionally humbling scene.

(Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published on August 11, 2008. It was updated and expanded on June 23, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

Kolker, Robert P., and Nathan Abrams. Kubrick: An Odyssey. Pegasus Books, 2024.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Walker, Alexander, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Rev. and expanded. Norton, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review