The Definitives

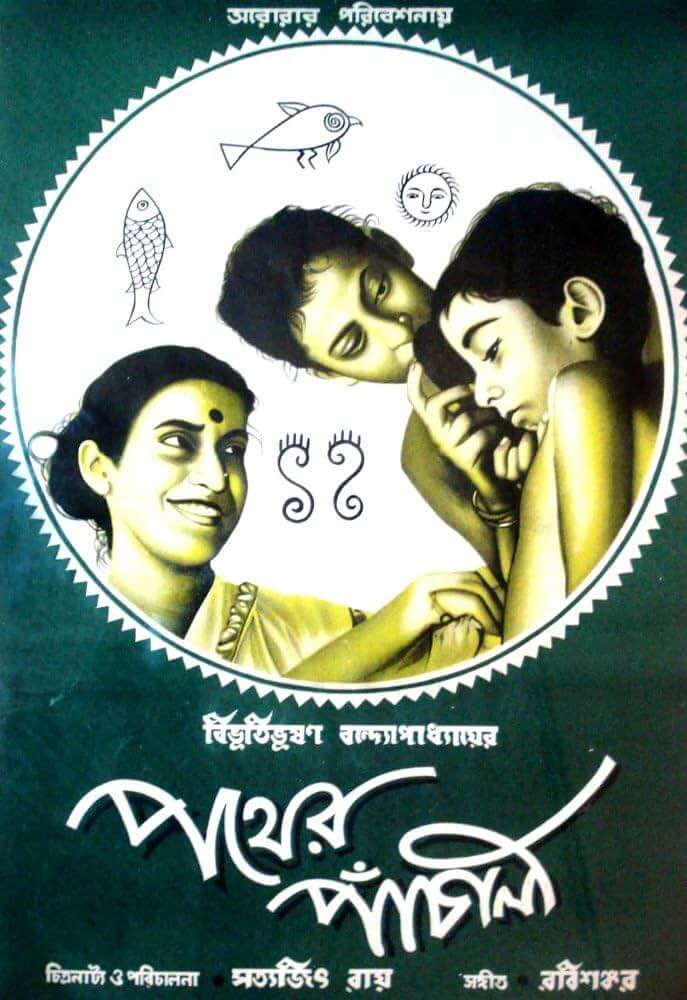

Pather Panchali (1955)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

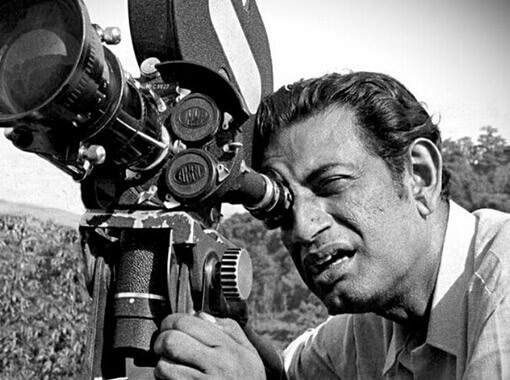

Satyajit Ray made films about how people in India negotiate their surroundings and culture. His boundless humanism defined his work, which began in 1955 with Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road), the first entry in his celebrated Apu Trilogy, followed by Aparajito (1956, The Unvanquished) and Apu Sansar (1959, The World of Apu). A Bengali filmmaker who purveyed characters with vast emotional depth, Ray avoided the ideological and political, and he approached human beings as individuals who, regardless of their views, were allowed to speak their minds. Ray, whose films earn comparisons to the work of Jean Renoir for their interest in the complexity of human beings, was described by Renoir as “the father of Indian cinema.” However, Ray’s distinct perspective and poetic style developed in contrast to primary modes of Indian cinema, neither attuned to the popular commercial Hindi industry that dominates much of the country’s cinematic output nor invested in the emergence of activist political filmmaking, as with his social realist contemporaries Mrinal Sen or Ritwik Ghatak. Based on the novel by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee, Pather Panchali, though set in a rural village in the 1930s, has a timeless, natural style that many at the time confused with documentary realism, and when the film debuted, Ray’s style earned comparisons to ethnographic documentary pioneer Robert Flaherty. A closer inspection of the film and its creation, Ray’s divergence from other Indian cinema, and further, his uniqueness among all of cinema’s authorial voices, reveals his debut as an artwork attesting to the director as a lyrical observer of humanity.

Ray’s individualism, and the exceptionality of his films within his country’s national cinema, become apparent when characterizing the Indian film industry (understanding, of course, that any such characterization of an entire industry remains dependent on some generalizations). Indian film had developed in a trajectory similar to that of Hollywood, where, in the early 1920s and 1930s, a few major studios concentrated on cheap production costs and high profits. Early Indian films had neither the advanced facilities nor the inclination to make more sophisticated efforts; instead, unpolished films contained feats of action, stage-like performances, and mythological subject matter in an economical, mostly self-contained industry. An inbuilt audience in the hundreds of millions established a stable marketplace for these Hindi-language films—meaning production, distribution, and exhibition took place within India’s borders. Whereas Hollywood titles dominated the screens of other countries around the world, leaving only a small percentage for the local, undeveloped national film industries, India retained more than 60 percent of their own films on their theater screens. Moreover, after India achieved independence from the British Empire in 1947, the nationalized interests of the Indian National Congress emphasized the need for a strong national cinema in the wake of India’s growing capitalism, and the volume of Indian popular films steadily increased to become the largest film industry in the world.

Over time, various tendencies of Indian film emerged, the largest of which remains the Mumbai (formerly Bombay) studio system, colloquially referred to as Bollywood. Predominantly using the Hindi language and boasting budgets four-times higher than regional Indian productions, the Mumbai industry’s output is often how the Western world characterizes Indian cinema. Examples of these popular films from the mid- to late-twentieth century find their roots in Indian poetry, theater, and painting, while their methods seem melodramatic or whimsical to many Western viewers. Stylistically, such commercial films contain rich colors and expressivity; they feature music, song and dance, and often pronounced emotions within a bombastic approach to storytelling that may seem erratic and tangential to audiences accustomed to Hollywood’s comparatively linear methods. Scholar Wimal Dissanayake describes Mumbai cinema as having “issues of tempo, fragmentation, chaos, and over-stimulation” with “endless circularities, digressions and detours, and plots within plots.” Given how they are constructed in the cheaper filmmaking facilities available, the results often look shoddily assembled or haphazard compared to mainstream Hollywood fare. Although, contemporary Bollywood films draw influence from Hollywood, giving them a slightly more polished look than those made during Ray’s time. Non-Mumbai regional cinemas from Kolkata, Madras, or other smaller areas that use local languages (Bengali, Marathi, Tamil, and Telegu) prove less popular and less technically accomplished.

Over time, various tendencies of Indian film emerged, the largest of which remains the Mumbai (formerly Bombay) studio system, colloquially referred to as Bollywood. Predominantly using the Hindi language and boasting budgets four-times higher than regional Indian productions, the Mumbai industry’s output is often how the Western world characterizes Indian cinema. Examples of these popular films from the mid- to late-twentieth century find their roots in Indian poetry, theater, and painting, while their methods seem melodramatic or whimsical to many Western viewers. Stylistically, such commercial films contain rich colors and expressivity; they feature music, song and dance, and often pronounced emotions within a bombastic approach to storytelling that may seem erratic and tangential to audiences accustomed to Hollywood’s comparatively linear methods. Scholar Wimal Dissanayake describes Mumbai cinema as having “issues of tempo, fragmentation, chaos, and over-stimulation” with “endless circularities, digressions and detours, and plots within plots.” Given how they are constructed in the cheaper filmmaking facilities available, the results often look shoddily assembled or haphazard compared to mainstream Hollywood fare. Although, contemporary Bollywood films draw influence from Hollywood, giving them a slightly more polished look than those made during Ray’s time. Non-Mumbai regional cinemas from Kolkata, Madras, or other smaller areas that use local languages (Bengali, Marathi, Tamil, and Telegu) prove less popular and less technically accomplished.

Ray’s brand of filmmaking emerged as part of the national government’s desire to create an alternative New Indian Cinema, with a drive toward social awareness and a conscious departure from commercial cinema. Many in India believed that the country, with its newly achieved independence from British colonial rule, would be better served by social realism, polished filmmaking, and authentic storytelling, as opposed to the cheap, fanciful, and often outlandish releases that pervaded the Indian film industry. In the 1960s, the Indian government established the Film Finance Corporation and the Indian Motion Picture Export Association—which eventually merged in 1980 to become the National Film Development Corporation—to foster social filmmaking for international distribution on the arthouse circuit. However, many of the films produced from this New Indian Cinema movement were unpopular; their primary market was, ironically, on the international scene, though many went unscreened by Western audiences. Even most Ray films, functioning within the edicts of the New Indian Cinema for the first years of his career, did not arrive in the U.S. until after his death in 1992, just after he became the first Indian filmmaker to receive an honorary Academy Award, launching a significant effort to restore his body of work.

Before becoming the so-called father of Indian cinema, Ray received his education in filmmaking not from formal training but by studying the craft of classic Hollywood and writing extensive, thoughtful film criticism and theory. He was “anxious to study films, not to make them,” he told interviewer Almay Benegal for the documentary Satyajit Ray (1984). Although he continued to see Bengali films from directors such as Bimal Roy and Nitin Bose, he watched Bengali films to learn how not to make films, calling them “false, unrealistic, shoddy, commercial in a bad way.” He determined that Indian films suffered from a lack of technical and actorly polish when compared to Hollywood or European cinema, and he particularly cited John Ford, Ernst Lubitsch, William Wyler, Frank Capra, and David Lean as role models in his understanding of the craft. During this period, Ray also studied documentarian Flaherty, whose aesthetics from Nanook of the North (1922) to the Sabu-starrer Elephant Boy (1937) instilled a pseudo-realist approach, capturing Nature and indigenous people with a conflicting sense of control and veracity. Whenever Ray could get his hands on a print of a Jean Renoir film, he did. Ray also considered Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1938) one of the finest films ever made, and he admired Renoir’s humanist ideals and open-mindedness toward characters that another filmmaker would have judged harshly.

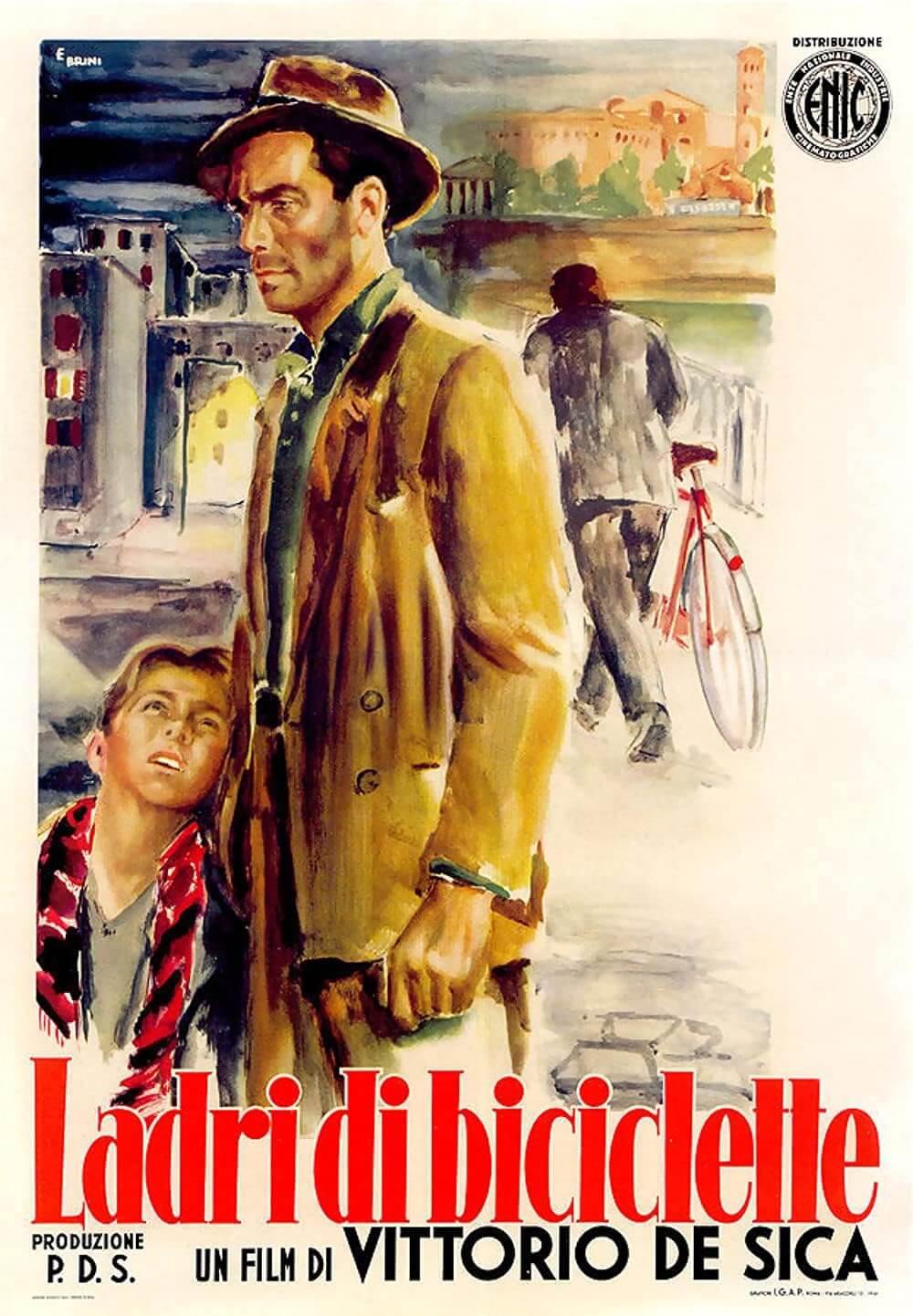

Ray, who helped found the Calcutta Film Society in 1946, used his affiliation with the Society to put himself in touch with people like Renoir, who had arrived in India to shoot The River in 1949. While Renoir would remain a lasting influence on Ray, the fledgling director’s encounter with the French during the production of The River led to Ray providing him with notes on the authenticity, or lack thereof, in the script by Renoir and author Rumer Godden, based on her 1946 novel. The film’s lack of representation of Indian characters in favor of an English family, despite its setting on the Ganges River, led to Ray’s later disapproval of The River for its deficient authenticity, although he did so in such a way that Renoir later validated his criticisms, stating “I had to see India through the eyes of a Westerner if I didn’t want to make horrible mistakes.” Elsewhere, Ray explored film during a formative trip to London in 1950, his only extended trip away from India. He spent several months sightseeing and filmgoing, and took in an astonishing ninety-nine films in all. His screening of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) during the trip was determinative of his early style and had convinced him to become a filmmaker. The qualities found in Flaherty and Renoir were evident in Italian Neorealism, Ray thought, where mannered filmmakers like De Sica and Roberto Rossellini were hailed for their labored-over approach to realist subjects and styles. After seeing Bicycle Thieves, Ray declared, “The Indian film maker must turn to life, to reality. De Sica and not DeMille, should be his ideal.”

Ray, who helped found the Calcutta Film Society in 1946, used his affiliation with the Society to put himself in touch with people like Renoir, who had arrived in India to shoot The River in 1949. While Renoir would remain a lasting influence on Ray, the fledgling director’s encounter with the French during the production of The River led to Ray providing him with notes on the authenticity, or lack thereof, in the script by Renoir and author Rumer Godden, based on her 1946 novel. The film’s lack of representation of Indian characters in favor of an English family, despite its setting on the Ganges River, led to Ray’s later disapproval of The River for its deficient authenticity, although he did so in such a way that Renoir later validated his criticisms, stating “I had to see India through the eyes of a Westerner if I didn’t want to make horrible mistakes.” Elsewhere, Ray explored film during a formative trip to London in 1950, his only extended trip away from India. He spent several months sightseeing and filmgoing, and took in an astonishing ninety-nine films in all. His screening of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) during the trip was determinative of his early style and had convinced him to become a filmmaker. The qualities found in Flaherty and Renoir were evident in Italian Neorealism, Ray thought, where mannered filmmakers like De Sica and Roberto Rossellini were hailed for their labored-over approach to realist subjects and styles. After seeing Bicycle Thieves, Ray declared, “The Indian film maker must turn to life, to reality. De Sica and not DeMille, should be his ideal.”

With this ideal in mind, Ray set out to make Pather Panchali over the course of two years, working on it intermittently as he maintained a career in advertising. The project first came to Ray in 1950, when he was asked to illustrate a children’s version of the hugely popular book Pather Panchali, first published in a serialized Bengali periodical between 1928 and 1929, and then in novel form in 1929. Ray was charmed and engrossed by the text, and he resolved to adapt the material as his first film. By this time, the novel had already become a classic in Bengal and ensured the proposed film an inbuilt audience. Ray wrote his treatment and composed detailed sketches of his proposed film to interest producers and investors before acquiring the rights to the Banerjee’s novel. He eventually met with Banerjee’s widow who approved of the project, knowing of Ray’s talented grandfather and father, both famous artisans. Many censured her decision given Ray’s inexperience as a filmmaker, but she nonetheless remained supportive of the fledgling director throughout the next half-decade, as Ray slowly progressed on his first film. For two years, Ray pitched his film idea to potential investors, but many balked at his notion of shooting in real locations with amateur actors; and they could not imagine an Indian motion picture without song and dance. “They believed only in a certain kind of commercial cinema,” Ray wrote later. “But one kept hoping that presented with something fresh and original and affecting, they would change.” By 1952, Ray had convinced no investors to support his unconventional project. He resolved to borrow money from various friends and his insurance company to shoot footage that, over time, convinced investors to support the entire production.

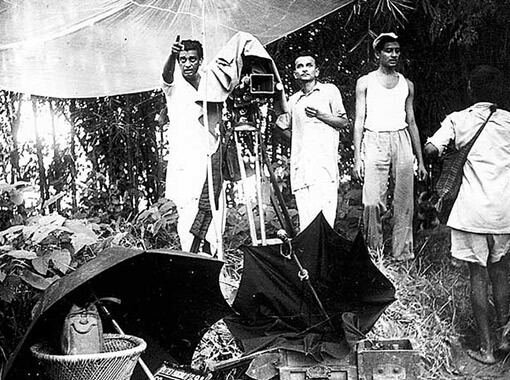

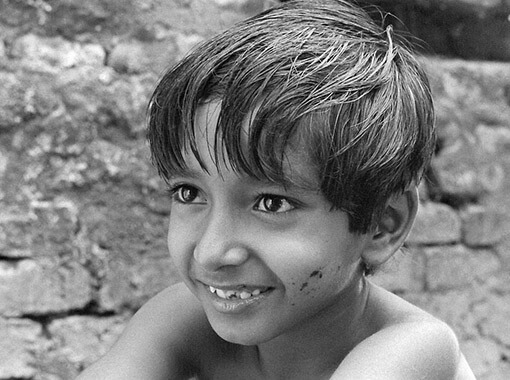

Ray filmed Pather Panchali in sequence on the Bengali countryside, using untrained actors and subpar equipment. He taught himself the practice and artistry of filmmaking as he went along. This has resulted in many film scholars noting how the production looks to improve in its craft as the story advances. Always scraping by, the production seldom had access to the right lenses early on, and some critics have noted arbitrariness of the lenses and how they’re used in the first half. Intermittent shooting began in 1952, mired by the production’s deficient budget, meager technical facilities, and the lack of experience among the director and his band of friends behind the scenes. They shot in two primary locations: the village of Boral, where the ancestral home of the story’s family and a nearby pond were located; and also, a field some hundred miles away. Ray found actors young and old with stage experience. Most, aside from Subir Banerjee, the boy who plays Apu, had acted before. But as Apu has few lines and often remains a spectator to the film’s drama, he wasn’t required to give an excellent performance, just react as a child would naturally. The director’s most significant find was Chunibala Devi for Auntie, the friendly neighbor of the central family. She was an octogenarian who uncannily met the author’s description of the character, and yet she served Ray’s needs: she looked the distinguished part, had been an actress earlier in the century, and maintained a sharp enough wit to remember lines and give a thorough performance—despite living in Calcutta’s red-light district, where she supported an opium addiction.

A modest amount of shooting commenced in 1953 as financing allowed, and Ray’s continuous struggle to get the film made was encouraged by the success of Far Eastern filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa, whose triumph with Rashomon (1950), which Ray had seen at an Indian film festival, suggested that culturally specific films from the East would play well in the West. As Ray’s production ran out of money, he asked his wife to pawn her jewels, which she did in a detail later acknowledged in Ray’s The Music Room (1958), where an aristocrat clings to his former glory by pawning jewels to throw elaborate recitals in his home—Ray was the aristocrat here, pouring his economic livelihood into his appreciation of art. Even as financing remained a constant strain on Ray’s progress, he felt encouraged by the footage, the naturalism of the performances, especially Devi, and the sense that he was creating something unique for Indian cinema. But once again, the production ran out of money. Shooting halted for nearly a year, and during that time, Ray worried that his young actors would grow up or reach puberty, or worse, that his elderly actress might not last.

A modest amount of shooting commenced in 1953 as financing allowed, and Ray’s continuous struggle to get the film made was encouraged by the success of Far Eastern filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa, whose triumph with Rashomon (1950), which Ray had seen at an Indian film festival, suggested that culturally specific films from the East would play well in the West. As Ray’s production ran out of money, he asked his wife to pawn her jewels, which she did in a detail later acknowledged in Ray’s The Music Room (1958), where an aristocrat clings to his former glory by pawning jewels to throw elaborate recitals in his home—Ray was the aristocrat here, pouring his economic livelihood into his appreciation of art. Even as financing remained a constant strain on Ray’s progress, he felt encouraged by the footage, the naturalism of the performances, especially Devi, and the sense that he was creating something unique for Indian cinema. But once again, the production ran out of money. Shooting halted for nearly a year, and during that time, Ray worried that his young actors would grow up or reach puberty, or worse, that his elderly actress might not last.

While on hiatus, Ray had a chance meeting with Monroe Wheeler, the Director of Publications and Exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Wheeler was introduced to Ray during his brief trip to India to explore textiles in Calcutta for exhibition in MoMA. Ray showed Wheeler early stills of Pather Panchali and piqued his interest. Wheeler, in turn, contacted the museum and arranged for a rough cut to be screened by a representative who described Ray’s project as an anticipated “documentary film” that “magnificently projected by the village folk without a whiff of ham”—a mischaracterization suggesting that Ray had made a documentary in the style of Robert Flaherty. Since Flaherty’s brand of documentary attracted audiences, distributors became interested in Pather Panchali well before its completion. Around the same time, funding from a government grant provided the resources Ray needed to complete his production. Dr. B.C. Roy, the Chief Minister of the Government of West Bengal, was shown edited footage of the production through a mutual connection of Ray’s mother in hopes that the government would provide funding. Similar to Wheeler and many officials who inspected the footage, Roy believed the project to be a documentary. Regardless, the government’s interest in supporting a socially conscious national cinema movement, which would eventually develop into the New Indian Cinema that emerged in the 1960s, meant Ray received a grant and could complete his film. The deal to finish his work, however, left the director with no income for his efforts and no rights to the international release.

Even with funding secured, Ray’s production was tested by the monsoon season, which allowed him extra time to reconsider his approach, as his cast and crew waited for the rains to subside. During this time, he thought and rethought his process, planned nearly every shot in detail, and edited the existing footage together. In his subsequent films, he continued the process of meticulous preplanning and editing during production, allowing him insight and control over the end result. Still, the funding meant Ray was now on a deadline. He had agreed to have the film ready by May 1955 for a screening at MoMA, meaning he had to scramble to complete shooting, edit the picture, add music, and loop the actors’ voices where necessary. Wheeler had already sent a representative to Calcutta to check on Ray’s progress: John Huston, who was going to India to scout locations for The Man Who Would Be King (eventually made in 1975), saw a rough cut of scenes from Pather Panchali and noted that, while beautiful, there was perhaps too much meandering on the screen. Whether or not Huston understood the project’s desire to capture rural Bengali life, he nonetheless recognized Ray’s work as that of a great filmmaker. Meanwhile, Ray and his production team lived inside the Bengal Film Laboratories for a week to complete a print in time for his MoMA deadline.

Musician Ravi Shankar was not yet an international sensation when Ray asked him to compose the film’s score, but his celebrity in India was enough that scheduling a recording session was difficult, especially given the short deadline. Due to his intense touring schedule, Shankar’s music was recorded over the course of eleven hours, lasting well into the next morning. Shankar improvised scene after scene, with only vague ideas about how the music should be played, having seen just half of the completed film. Ray thought the entire recording process was hectic, as Shankar would work out his tunes on a sitar or hum them, while Aloke Dey, Shankar’s flutist, raced to transcribe the notes to the page to be polished later. Today, the Apu theme on Shankar’s bamboo flute, which echoes in Aparajito and Apu Sansar, seems eternal and sophisticated. Shankar had captured the enduring quality of Apu that would continue throughout the trilogy. That the score was assembled in such a chaotic recording session remains a small wonder given its emotional impact on the final film. Still, before he could deliver Pather Panchali to the West, Ray needed to secure the approval of the West Bengal Government, since they had produced the film. Screening an incomplete rough cut for Roy and other officials, Ray was reproached for his melancholy and uncertain ending; but Ray’s version ultimately survived the critique. He had followed the novel, after all, and many believed the public would react negatively to any changes to the source material.

Musician Ravi Shankar was not yet an international sensation when Ray asked him to compose the film’s score, but his celebrity in India was enough that scheduling a recording session was difficult, especially given the short deadline. Due to his intense touring schedule, Shankar’s music was recorded over the course of eleven hours, lasting well into the next morning. Shankar improvised scene after scene, with only vague ideas about how the music should be played, having seen just half of the completed film. Ray thought the entire recording process was hectic, as Shankar would work out his tunes on a sitar or hum them, while Aloke Dey, Shankar’s flutist, raced to transcribe the notes to the page to be polished later. Today, the Apu theme on Shankar’s bamboo flute, which echoes in Aparajito and Apu Sansar, seems eternal and sophisticated. Shankar had captured the enduring quality of Apu that would continue throughout the trilogy. That the score was assembled in such a chaotic recording session remains a small wonder given its emotional impact on the final film. Still, before he could deliver Pather Panchali to the West, Ray needed to secure the approval of the West Bengal Government, since they had produced the film. Screening an incomplete rough cut for Roy and other officials, Ray was reproached for his melancholy and uncertain ending; but Ray’s version ultimately survived the critique. He had followed the novel, after all, and many believed the public would react negatively to any changes to the source material.

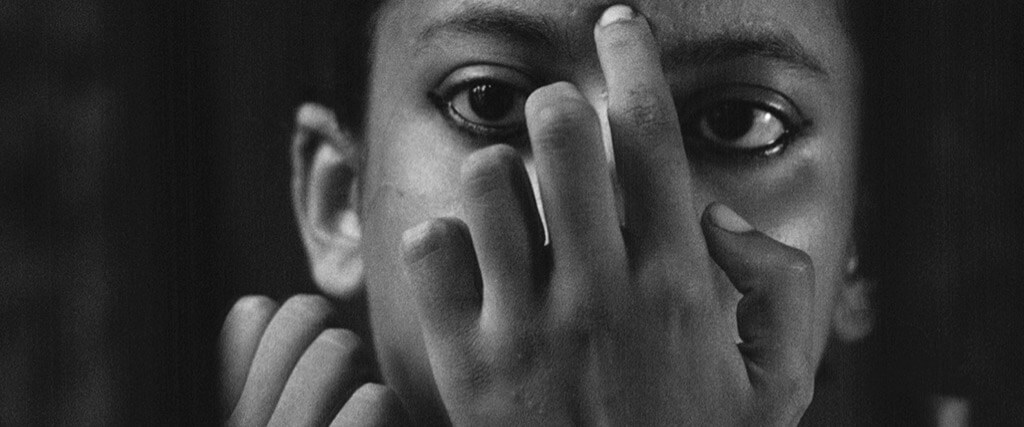

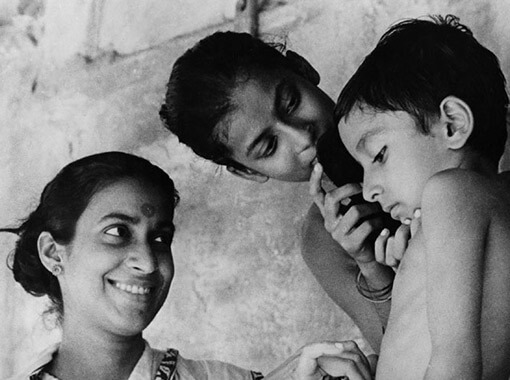

Set in the crumbling, ancestral Bengali village of Nischindipur, the screen story follows one family’s survival through Ray’s observations on life, death, and Nature. The father, the optimistic Harihar (Kanu Banerjee), serves as a traveling Hindu priest and leaves his careworn wife, Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), to care for the family and tend to the household while he is gone. Their spirited and curious daughter Durga (Uma Das Gupta) is soon joined by a new brother. The birth of a second child brings an infant boy named Apu into the family. Together, they live among decaying stones with Indir “Auntie” Thakrun (Chunibala Devi), an elderly woman and neighbor who relies on the family’s care. As years pass and Apu (Subir Banerjee) grows into a young boy, Sarbajaya dreams of a better life, worrying about her husband’s lack of income, having enough rice and clothes, finding a husband for Durga, and her new son. “How will he survive?” she asks. “Was he even born to survive?” Though Harihar assures his wife that he will soon find work and all will be resolved, Sarbajaya laments their immobility. “I had lots of dreams once,” she reflects in a sentiment echoed by the sound of a locomotive in the distance, and the possibility and promise of modernity. Durga dreams of seeing the train someday and, after sneaking away with Apu, spies the machine from a field as it passes through the landscape, its plumes of smoke leaving a trail in the sky, carrying the promise of adventure, an unknown and limitless world that seems impossibly far away.

Everyone in Pather Panchali dreams of something better, but not everyone sees their dreams come to fruition. Though Ray depicts the hardships of the idyllic village, rural lifestyle, and household in poverty, dreaming and endurance define these characters, sometimes in tragic ways. When Durga and Apu return from seeing the train, they find Auntie seated on the ground, unresponsive and dead. An earlier scene where Auntie asks if an elderly woman, too, can’t have dreams for a better life, reverberates through her death, and Durga’s. As if defiantly welcoming the sublimity of Nature in the wake of Auntie’s passing, Durga embraces a torrential monsoon downpour, though her impulsive behavior leads to her taking ill. Apu, having watched Durga play from a distance, seems to learn a valuable, if hard-won lesson. With Harihar away looking for work, Sarbajaya cares for the sickly Durga, who succumbs to her illness during a stormy night. In a tragic irony, Harihar has secured a job in the holy city of Benares. After Durga’s death, the family resolves to leave, and Apu, having been a mostly passive observer for much of the drama, carries its lessons with him into a new beginning.

The book incorporated details from the author’s life into a sweeping tale populated with many more characters than appear in the film, and his descriptions showcased the author’s love of Nature and country living. Even so, the film follows the same primary characters as the book. Although later in his career Ray would become famous for his elaborate scripts noting every detail from costumes to camera angles, Pather Panchali had no traditional screenplay; instead, Ray maintained a detailed treatment with director’s notes, while most of his dialogue came from the novel. But Ray’s adaption streamlines much of the plot, removing dozens of characters to focus primarily on Sarbajaya’s struggle to maintain her household, often with a touch of vinegar; the sister Durga and her adolescent rebellion; and to a lesser extent Apu, who is peripheral in the narrative. Ray sought to capture the rambling quality of a small village. But Ray supplied interconnectedness between the characters, especially among the children to Auntie. And whereas Auntie dies early in Banerjee’s novel, she remains a major presence in the film until her death, which Ray relocates from a village surrounded by adults to a lonely death in the forest, where the children find her. Ray’s changes imply the course of life, from youth to old age to death, which in turn makes Durga’s premature death even more heartbreaking for Apu.

The book incorporated details from the author’s life into a sweeping tale populated with many more characters than appear in the film, and his descriptions showcased the author’s love of Nature and country living. Even so, the film follows the same primary characters as the book. Although later in his career Ray would become famous for his elaborate scripts noting every detail from costumes to camera angles, Pather Panchali had no traditional screenplay; instead, Ray maintained a detailed treatment with director’s notes, while most of his dialogue came from the novel. But Ray’s adaption streamlines much of the plot, removing dozens of characters to focus primarily on Sarbajaya’s struggle to maintain her household, often with a touch of vinegar; the sister Durga and her adolescent rebellion; and to a lesser extent Apu, who is peripheral in the narrative. Ray sought to capture the rambling quality of a small village. But Ray supplied interconnectedness between the characters, especially among the children to Auntie. And whereas Auntie dies early in Banerjee’s novel, she remains a major presence in the film until her death, which Ray relocates from a village surrounded by adults to a lonely death in the forest, where the children find her. Ray’s changes imply the course of life, from youth to old age to death, which in turn makes Durga’s premature death even more heartbreaking for Apu.

The first screening of Ray’s completed film took place in New York, oddly enough, as the director had scrambled so fast to piece together what was called The Story of Apu and Durga to meet his MoMA deadline, he did not have time to view his work in its entirety. The screening went well, and Wheeler sent his congratulations, whereas in India the West Bengal Government handed over distribution to Aurora Films, which set a release date of August 26, 1955. Without a marketing budget, Ray himself designed posters and distributed them in Calcutta to spread the word. The film’s box-office was slow at first. Pather Panchali opened in a single theater in Calcutta, and it took weeks for word to spread of its impact. Indian critics, among them Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, appreciated the film’s “sense of beauty, its bursts, of visual ecstasy and of mental passion” rather than the strain of ethnographic realism that attracted Western viewers. Within a few weeks, Ray’s first film had earned a modest box office and transitioned out of Indian theaters, and Pather Panchali would soon arrive on the international festival circuit. As the book concentrated on village life and met with the ideals of New Indian Cinema, Pather Panchali would be, according to Ray scholar Chandak Sengoopta, “a serious programme for the reform of Indian cinema that was shaped implicitly by the nationalistic optimism of the period.” In addition to being the first major work of Indian realism, Pather Panchali also became the first Indian film screened for Western audiences. Other social realist filmmakers, such as Nimai Ghosh and K.A. Abbas, sought to make important movies for the new India, although their efforts were not as impactful as Pather Panchali on an international scale.

Given the lack of Indian cinema to appear stateside, U.S. distributors avoided booking the film in any great numbers, despite its win of the Special Jury Prize at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival. Western critics, meanwhile, failed to recognize the film’s artistic significance, even while praising its naturalism and Ray’s sensitivity to the subject matter. In the U.S., reviewers and distributors alike continued to characterize Pather Panchali as a documentary of sorts, ignoring the film’s literary origins, acting, music, or photography. An article in New York magazine called the film “a worthy descendant of the tribe” associated with Flaherty’s depictions of other cultures. They overlooked its fictional origins and failed to recognize that, unlike Italian Neorealism, there was not necessarily a need for a grand statement in Pather Panchali; rather, the film’s warmth exists in the viewer’s capacity for empathy and appreciation of the beauty onscreen. “In our sophistication we had learned to react to stories and situations, themes and symbols in our films,” wrote critic John Flaus years later. “We had lost the habit of reacting to people. We were unprepared in our art for compassion, unspoiled and unqualified.”

The film also screened in 1957 at the Robert Flaherty Foundation, an institution founded in 1955, after Flaherty’s death in 1951, to support the documentaries and film art of other cultures. After the private screening, Flaherty’s brother wrote that Pather Panchali fulfilled the Foundation’s credo “to cherish and communicate the humanity common to all peoples.” As Sengoopta noted, it was easier for Western viewers to characterize the film as universally human—or just like us, as a lot of U.S. reviews mentioned—as opposed to embracing the similarities and differences between the specific Indian culture represented and the spectating U.S. culture. When Pather Panchali and Aparajito were both screened at the Foundation in 1958 with Ray in attendance, they were thought to have “a rebel ring” to them against the booming Indian film industry products. This was true enough, but not in the way the Foundation thought. Flaherty’s widow needed to be convinced that Ray had not used real villagers to shoot these films; rather, the children were students in Calcutta and the parents were well-educated professionals, and some of them had stage experience. In the subsequent years, perhaps due to their disappointment with Ray’s status as a non-documentarian, the Foundation avoided screening other Ray films.

The film also screened in 1957 at the Robert Flaherty Foundation, an institution founded in 1955, after Flaherty’s death in 1951, to support the documentaries and film art of other cultures. After the private screening, Flaherty’s brother wrote that Pather Panchali fulfilled the Foundation’s credo “to cherish and communicate the humanity common to all peoples.” As Sengoopta noted, it was easier for Western viewers to characterize the film as universally human—or just like us, as a lot of U.S. reviews mentioned—as opposed to embracing the similarities and differences between the specific Indian culture represented and the spectating U.S. culture. When Pather Panchali and Aparajito were both screened at the Foundation in 1958 with Ray in attendance, they were thought to have “a rebel ring” to them against the booming Indian film industry products. This was true enough, but not in the way the Foundation thought. Flaherty’s widow needed to be convinced that Ray had not used real villagers to shoot these films; rather, the children were students in Calcutta and the parents were well-educated professionals, and some of them had stage experience. In the subsequent years, perhaps due to their disappointment with Ray’s status as a non-documentarian, the Foundation avoided screening other Ray films.

Ray’s associations with Flaherty, then, stem from Western viewers looking at his work through preconceived notions about non-Anglo cultures, seeing them as “primitive” or “exotic,” and having a certain ethnographic sameness. Viewers at the time also maintained a lack of knowledge about the source material or Indian film industry, assuming that an Indian filmmaker could not produce a work that created a sense of realism, while at the same time being entirely fictional. Then again, people were convinced of Nanook of the North’s realism too, and Flaherty’s tactics were later shown to be manipulative. Nanook of the North seemed to document the life of an Inuit hunter in the Canadian wilderness, but Flaherty was eventually revealed to have guided the dramaturgy more than he initially admitted. After all, a cursory examination of Ray’s camera angles, use of editing and montage, and the polished quality to his scenes reveals a distinctly mannerist approach not traditionally associated with a docu-style. However, as documentaries were comparatively uncommon in 1950 compared to their omnipresence today, it’s easy to understand why critics and the Flaherty Foundation mischaracterized Pather Panchali as a documentary subject.

Nevertheless, Ray made clear aesthetic choices about how to shoot Pather Panchali, and a conscious decision to adopt De Sica-esque realism and the humanist observation of Renoir, both through a defined aesthetic. Ray once said of a director’s approach to realism, “There is no ready-made reality which he can straightaway capture on film. What surrounds him is only raw material. Objects, locales, people, speech, viewpoints—everything must be carefully chosen, to serve the ends of his story. In other words, creating reality is part of the creative process, where the imagination is aided by the eye and the ear.” In aide of creating this reality, Ray despised improvisations and only occasionally used them on set; he was meticulous in his vision. His scripts were famous for charting every detail from the costumes to the angles that would be used. Even so, Ray improvised some of Pather Panchali’s most beautiful and memorable images: the shot of the water spiders, a shot of the train smoke against the sunlight in the distance, and a climactic scene where Apu throws a necklace into a pond. The necklace was the topic of an argument between Durga’s mother and a neighbor woman, who accuses Durga of stealing it. After his sister’s death, Apu finds the necklace among her things. In the film’s most heartrending passage, Apu resolves to discard the evidence in a nearby pond. The algae slowly conceals the location of the necklace’s splash, as if sealing off his sister’s secret in his memory.

Ray’s most significant thematic addition to Banerjee’s novel was to place greater emphasis on Apu’s growth as a progression, rather than a cyclical pattern of the young members of a family following in the well-treaded grooves of their parents in the book. Banerjee’s use of time was characteristically Indian and based in tradition, whereas Ray followed the new ideology of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru; not so much his ideas of socialism and industrialization, but his argument that “there is no going back to the past; there is no turning back even if this was thought desirable. There is only one-way traffic in time.” For Ray, this was a personal touch in a trilogy that, as he continued with Pather Panchali‘s two sequels, which had no direct source material, his stories became increasingly autobiographical. Ray expanded on characters that were important to him, from the mother who, like his own, always works in Pather Panchali, or the printing presses of Aparajito, which recalled the presses used by his grandfather and father. Apu grows, and continues to grow, throughout the Apu Trilogy, forging his own path, as India should, as Ray seems to say, rather than going back and keeping the traditions of his parents. With this in mind, the subsequent films, which find Apu facing Western values that clash with his rural Indian upbringing, have almost no nostalgia for or reference to the preceding titles, aside from a few notes from Ravi Shankar’s original theme.

Ray’s most significant thematic addition to Banerjee’s novel was to place greater emphasis on Apu’s growth as a progression, rather than a cyclical pattern of the young members of a family following in the well-treaded grooves of their parents in the book. Banerjee’s use of time was characteristically Indian and based in tradition, whereas Ray followed the new ideology of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru; not so much his ideas of socialism and industrialization, but his argument that “there is no going back to the past; there is no turning back even if this was thought desirable. There is only one-way traffic in time.” For Ray, this was a personal touch in a trilogy that, as he continued with Pather Panchali‘s two sequels, which had no direct source material, his stories became increasingly autobiographical. Ray expanded on characters that were important to him, from the mother who, like his own, always works in Pather Panchali, or the printing presses of Aparajito, which recalled the presses used by his grandfather and father. Apu grows, and continues to grow, throughout the Apu Trilogy, forging his own path, as India should, as Ray seems to say, rather than going back and keeping the traditions of his parents. With this in mind, the subsequent films, which find Apu facing Western values that clash with his rural Indian upbringing, have almost no nostalgia for or reference to the preceding titles, aside from a few notes from Ravi Shankar’s original theme.

John Flaus described Pather Panchali as “an act of sublimity” for its closeness with Nature and natural human behavior—the way it appears less determined by formal approaches than the feelings and relationships of people in the natural world, far removed from the affectations or pretenses of commercial filmmaking. Ray’s observations are indeed extensive, capturing daily life on the Bengali countryside from beyond a directed perspective, beyond the child’s point-of-view that is often associated with the film. His camera witnesses things Apu does not, such as the slow decline of Auntie or Sarbajaya’s worry for her family, and in that, Ray helps his audience realize that empathy is not bound by class, national borders, races, or cultures. Curiously, Ray later received criticism for adopting Western styles, formal touches, and narrative structures in his work, suggesting his own output could hardly be called purely Indian, given the significant amount of influence he took from other filmmakers throughout the world. Many critics and scholars have used this quality about his films to pinpoint their universality to the human experience; others see it as a result of the lasting influence of British colonialism left on Indian culture. Given his influence from filmmakers around the world and his distinctly Indian subjects, Ray’s output remains unique among all others. Pather Panchali, more than its social significance within Indian culture, film history, or even Ray’s oeuvre, endures because, quite simply, Ray captures the beauty of the human condition.

Bibliography:

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Rethinking Indian Popular Cinema Towards Newer Frames of Understanding” Rethinking Third Cinema. Gunerante, Anthony R., and Wimal Dissanayake, editors. Routledge, 2003.

Ganguly, Keya. Cinema, Emergence, and the Films of Satyajit Ray. University of California Press, 2010.

Flaus, John. “The World of Satyajit Ray.” Senses of Cinema, no. 72, Oct. 2014, pp. 1-13.

Ray, Satyajit and Sandip Ray. Satyajit Ray on Cinema. Columbia University Press, 2011.

Ray, Satyajit. On Cinema. Ananda Pubs, 1982.

—. Our Films Their Films. Orient Longman, 1976.

Robinson, Andrew. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye. Second Edition, I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Roy, Binayak. “Ray: The Last Phase.” Film International, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2012, pp. 42-52.

Sengoopta, Chandak. “‘The Fruits of Independence’: Satyajit Ray, Indian Nationhood and the Spectre of Empire.” South Asian History and Culture, vol. 2, no. 3, 01 July 2011, p. 374-396.

—. “‘The Universal Film for All of Us, Everywhere in the World’: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and the Shadow of Robert Flaherty.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, vol. 29, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 277-293.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review