The Definitives

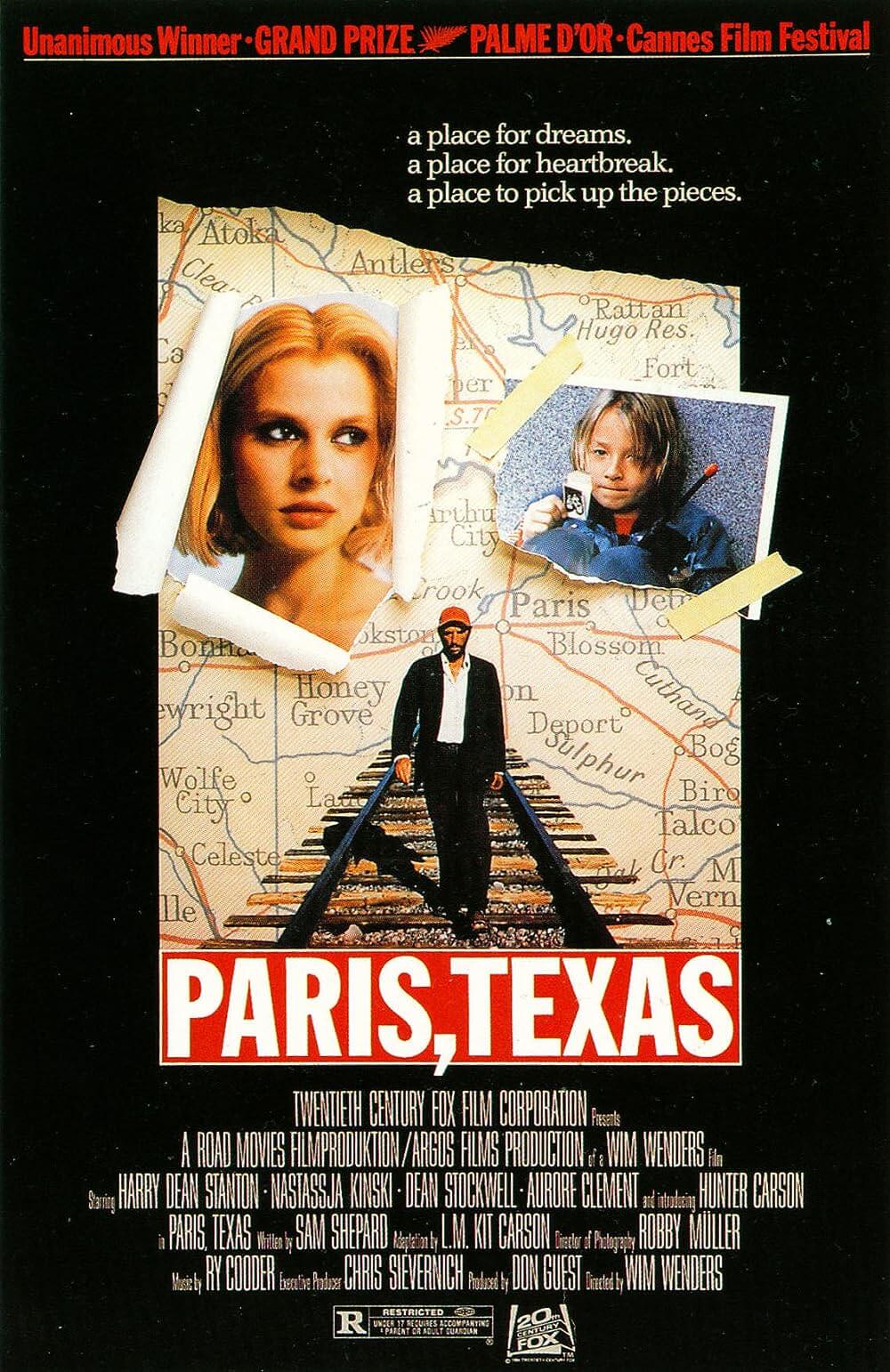

Paris, Texas

Essay by Brian Eggert |

After walking through desolate valleys, driving across empty highways, and navigating the claustrophobic indifference of Houston’s skyscrapers, the long journey in Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas reaches its destination in a peep show called The Keyhole Club. Inside, a husband and wife, estranged for several years, sit opposite each other, separated by a one-way mirror. They talk by phone in a scene recalling a visitor to a prison. But it’s not the wife, the object of the peep show, in prison; it’s the husband, whose failure to process his wife’s autonomy sent him spiraling. Wenders shoots the husband’s distanced, third-person retelling of the marriage’s explosion in a long, eviscerating monologue, aided by the poetry of Sam Shepard’s words, exquisite compositions by cinematographer Robby Müller, and a career-best performance by Harry Dean Stanton. Part confession, part apology, the speech supplies an overwhelming emotional release after two hours of silence, pain, and searching. With the film earning Wenders notoriety that elevated his status as an international auteur, including the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1984, Paris, Texas goes beyond the wandering, existential uncertainties and unresolved tensions of the director’s career to this point. It transcends his usual road movie archetypes and pressing alienation, and it enters the realm of an almost mythic quest for healing and reconciliation after the emotional fallout of masculine violence.

Stanton plays the amnesiac Travis, who trudges out of a middle-of-nowhere Texas desert with the telephone number for his brother, Walt (Dean Stockwell), in his wallet. Walt and his wife, Anne (Aurore Clément), have watched over Travis’ young son Hunter (Hunter Carson) for the last four years, ever since Travis’ wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski), Hunter’s mother, disappeared for reasons that remain unexplained until the final scenes. Travis’ mind has been wiped away, and he returns, unable to speak and barely aware of his former life. Walt drives out to recover his brother and bring him home to Los Angeles. Travis is reconnected with Walt as a brother and Hunter as a son, though their familial bond remains uncertain until a vital scene where Walt puts on a Super 8 home movie. The projected image features Walt and Anne visiting Travis and Jane several years earlier. The scene shows Travis and Hunter watching the home movie together, each remembering that they used to be part of the same family. Travis regards Hunter with a smile of faint recognition; Hunter looks at Travis, and both process what they see on the screen and associate their former familial roles with the person seated next to them. They remember, albeit tenuously. From this point forward, Paris, Texas becomes a search through memory and time to reestablish the brotherhood between Walt and Travis, the father and son bond between Travis and Hunter, and eventually, reconnect Hunter with Jane.

Apart from its sheer emotional resonance, many critics and scholars have discussed Paris, Texas, and most of Wenders’ work, as an ongoing conversion between one film and the next. Alexander Graf calls the director’s career “an experiment in progress […] even though the form of presentation in the individual films may vary or seem to build thematic blocks.” A larger conversation about where Paris, Texas falls in terms of Wenders’ development at this point in his career is certainly warranted. Its most immediate predecessor, the film-savvy The State of Things (1982), found Wenders exploring whether a film could work and whether a story could be told with the space between images. About a film crew in Portugal that runs out of money and film stock, The State of Things finds the crew spinning their wheels about what to do next. The film is widely interpreted as a reaction to Wenders’ experience shooting Hammett (1982) in Hollywood for the micromanaging producer Francis Ford Coppola, who demanded that the script be rewritten mid-production. Wenders lamented the experience, prompting him to leave the US for Europe to make The State of Things while Hammett was on hiatus. But that film only brought him to what he told Katherine Dieckmann was “a dead end.” Feeling lost in limbo and searching for a way out of a personal prison resonated with Wenders, so he sought to make a film that went somewhere.

Each of the ten features he had directed before Paris, Texas was concerned with the theme of characters searching for themselves, epitomized by his Road Trilogy that consisted of Alice in the Cities (1974), The Wrong Move (1975), and Kings of the Road (1976). Just as his characters drive in Europe and the United States, trying to locate an identity, Wenders’ career has a similar trajectory. Read any biography of Wenders, or regard his output as a filmmaker and artist, and you see the varied artistic projects and brief identities he has occupied in short bursts over his five-decade career. He was born in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 1945, and his journey ever since has been that of a nomad, alternating his home between Germany, where he emerged as part of the New German Cinema movement of the 1970s, then to Japan, Cuba, and the US. Besides filmmaking, he has explored photography, installation art, music videos, and commercials. Although he was among the international film community’s most treasured artists through the 1970s and 1980s, his output became more erratic and less cohesive as the years passed. In his seventies as of this writing, he continues making documentaries and features. And though his output has been steady, his last project to earn widespread praise and attention before the Oscar-nominated Perfect Days (2023) was Buena Vista Social Club (1999). Still, he keeps searching.

Whereas many of Wenders’ characters also search but never seem to get anywhere, Paris, Texas supplies a debatable exception. The film was conceived between Wenders and the multihyphenate Sam Shepard during the director’s time in Hollywood—a four-year period between 1978 and 1982 when Wenders had been planning Hammett. Wenders wanted Shepard to play Dashiell Hammett in his movie, but Shepard had other commitments. Instead, the director began discussing a different project with the actor, poet, playwright, and screenwriter. From the set of Paris, Texas in 1983, Wenders told journalist Melinda Camber Porter that he had long admired Shepard, whom he saw as someone searching for something in America. Just as Wenders had made several films about seeking answers about identity, home, and love in European cinema, Shepard seemed to be on a similar path with Motel Chronicles, a collection of prose and poems that inspired the film. A piece about a man who stands on the edge of a highway, staring at his suitcase, wondering if he should keep anything from it, only to set the suitcase on fire and walk into the desert, provided a launchpad for Wenders and Shepard. Following the tradition of Europeans who “go West” to find truth, Wenders discovered that an even more specific search took place in America. America was not a unified whole, and part of the country’s mythos was rooted in searching the West for answers, following romanticized notions instilled by the US government and implemented by pioneers, settlers, and cowboys.

Wenders and Shepard had been confronted with the notion that such searching was a continuous, never-ending journey that rarely ends in a resolution. In their collaboration, they resolved to make a film that confronted the false promise of the mythological Western frontier and, to a more significant extent, how those precepts play out in the relationships between men and women, specifically in Travis’ marriage to Jane. But contrary to their initial idea, both sought to tell a story that ends with Travis finding some answers—a sharp contrast to the films thus far in Wender’s body of work. Shepard delivered the script, which was poised for a ten-week shoot in Texas under Wenders’ production company, Road Movies. But after three weeks of shooting, Wenders had grown disenchanted with the story. According to L. M. Kit Carson, whose son played Travis’ boy, Hunter, Wenders had wanted to rethink the final two-thirds of the script completely. However, by the time he realized this, Shepard was in Iowa shooting Country (1984) for Touchstone Pictures. Wenders and Shepard had tried working long-distance, with Shepard dictating scenes over the phone in late-night conversations, but that process was slow. Carson, a screenwriter who had just completed work on Jim McBride’s 1983 remake of Breathless, helped reshape the later sections of Paris, Texas, while Shepard wrote the dialogue for crucial scenes, such as Travis’ monologue to Jane.

Fortunately, Wenders usually shot in sequence, believing that making films is about two different films—the one described in the initial script that you intend to make, and the one that emerges after the realities of shooting change your well-laid plans. Meaning, Wenders found his story in the process of making and telling it, and by shooting chronologically according to the script, he could adjust as he went. With Shepard giving his blessing to Carson to rewrite the ending, Wenders and his new writer set about rethinking the film while keeping investors at bay and the crew from becoming disenchanted by the chaos. But with the production progressing and money being tight, every night was a race, with Carson and Wenders discovering what would be shot the next day. Meanwhile, Stanton took his dinners in Carson’s hotel room to find a groove with Carson’s son so the onscreen father-son pair would feel natural. Their time together resulted in a comfortable, charming onscreen rapport between the two. Each day on the set, Wenders took the time to explain to everyone involved—not just the actors, not just Müller—what they were shooting and why. However haphazard the production may have seemed for the film workers at times, everyone involved experienced the narrative’s exploration, suggesting that Wenders required an experiential component to tell this searching story. For those behind the camera and in front of it, the quest was a healing process.

Fortunately, Wenders usually shot in sequence, believing that making films is about two different films—the one described in the initial script that you intend to make, and the one that emerges after the realities of shooting change your well-laid plans. Meaning, Wenders found his story in the process of making and telling it, and by shooting chronologically according to the script, he could adjust as he went. With Shepard giving his blessing to Carson to rewrite the ending, Wenders and his new writer set about rethinking the film while keeping investors at bay and the crew from becoming disenchanted by the chaos. But with the production progressing and money being tight, every night was a race, with Carson and Wenders discovering what would be shot the next day. Meanwhile, Stanton took his dinners in Carson’s hotel room to find a groove with Carson’s son so the onscreen father-son pair would feel natural. Their time together resulted in a comfortable, charming onscreen rapport between the two. Each day on the set, Wenders took the time to explain to everyone involved—not just the actors, not just Müller—what they were shooting and why. However haphazard the production may have seemed for the film workers at times, everyone involved experienced the narrative’s exploration, suggesting that Wenders required an experiential component to tell this searching story. For those behind the camera and in front of it, the quest was a healing process.

Some scholars have compared the narrative of Paris, Texas to John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). In their book The Films of Wim Wenders: Cinema as Vision and Desire, Robert Phillip Kolker and Peter Beicken write that Wenders’ film is “a response to the questions raised [by Ford’s film].” Initially, the similarities are unmistakable, with Travis and John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards emerging from the desert to reconnect with their estranged families. Both characters spend much of the middle of their respective films on a journey with a much younger counterpart: Travis with Hunter, and Ethan with Martin (Jeffrey Hunter). Both missions involve finding a young woman who disappeared after a violent encounter. Jane left after Travis’ violence sent him spiraling. In Ford’s film, Ethan’s niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) has been taken by Comanche raiders, so he sets out to rescue her. Both Jane and Debbie have since resigned themselves to another life of implied sexual servitude, the former in service at a peep show, the latter made one of the wives of the Comanche chief. In the end, though Travis and Ethan arrive at their intended destinations to recover their lost women and return them to their families, neither man can fully embrace the domestic lifestyle that their journey seems bent on restoring. Upon returning Debbie to her family, Ethan lingers at the doorway in a famous silhouette before returning to the desert. Travis, too, leaves his wife and child after reuniting them.

However, Travis has much more to reconcile than Ethan, and Wenders is more willing to confront his protagonist’s flaws directly than Ford would or could in 1956. Ford portrays Ethan’s racist anger toward Comanches and his fear that Debbie will be subjected to miscegenation; these obsessions bring Ethan to the brink of killing his niece when confronted with her in the finale. Ethan protects the solidarity of the frontier family, even though he cannot return to them in the end. Knowing he has these volatile prejudices inside him, he departs. Similarly, Travis leaves after he rebuilds the connection between Jane and Hunter. But his reasons for leaving are more complicated, with Wenders and Shepard questioning the role of the family patriarch, who enforces his power position with violence. In Travis’ famous monologue to Jane at The Keyhole Club, Travis openly reconciles with his irrational jealousy and suffocating possessiveness over Jane. He remembers that Jane seemed dissatisfied with him, particularly during her postpartum depression, and he responded by physically restraining her in their home in a scene of domestic violence. She set fire to their trailer home, took Hunter, left the child with Walt and Anne, then disappeared. More than Ethan, Travis acknowledges that his expectations of Jane were unfair and that he had an unhealthy amount of love, dependence, and possessiveness toward her. In this sense, Paris, Texas is as much about Travis reaching Jane as the destination as it is about escaping the old version of himself.

Travis’ memory of past events occurs through several filters and barriers, making his reconciliation indirect. In physical terms, Travis and Jane sit in opposite rooms in the peep show parlor, separated by the one-way mirror. She cannot see Travis at first, and Travis turns his chair the other way when he speaks, the shot capturing both facing the same direction. Jane hears his voice on an intercom as Travis speaks into a telephone receiver. The setting feels like a confessional, juxtaposed with the activities that usually take place here. Moreover, Travis talks in the third person, beginning his monologue, “I knew these people. These two people. They were in love with each other.” Perhaps separating himself from his memories allows him to process better what remains unhealed, or maybe he is so removed from that version of himself that Travis sees his past as another identity altogether. In either case, when Travis finally turns to face her, Müller overlays Travis’ reflection on the one-way mirror atop Jane’s face in the opposite room, one face over the other, implying the shared trauma of their past. Despite the physical and psychological barriers between them, Travis, in his verbalization of their history, offers a more direct acknowledgment of his masculine jealousy and violence than Ethan.

Travis’ memory of past events occurs through several filters and barriers, making his reconciliation indirect. In physical terms, Travis and Jane sit in opposite rooms in the peep show parlor, separated by the one-way mirror. She cannot see Travis at first, and Travis turns his chair the other way when he speaks, the shot capturing both facing the same direction. Jane hears his voice on an intercom as Travis speaks into a telephone receiver. The setting feels like a confessional, juxtaposed with the activities that usually take place here. Moreover, Travis talks in the third person, beginning his monologue, “I knew these people. These two people. They were in love with each other.” Perhaps separating himself from his memories allows him to process better what remains unhealed, or maybe he is so removed from that version of himself that Travis sees his past as another identity altogether. In either case, when Travis finally turns to face her, Müller overlays Travis’ reflection on the one-way mirror atop Jane’s face in the opposite room, one face over the other, implying the shared trauma of their past. Despite the physical and psychological barriers between them, Travis, in his verbalization of their history, offers a more direct acknowledgment of his masculine jealousy and violence than Ethan.

In Wenders and Shepard’s poetic terms, Travis represents an archetypal patriarchal role in the American family, though he remains in conflict with that role. The incongruous title emphasizes Travis’ inner conflict by remarking on the cultural ties with Paris, as in the capital of France and the city in Texas. In their romantic associations, the two locations could not be more different. The idea of Paris is feminine, sensual, and distinctly European. Texas, meanwhile, conjures images of cowboy iconography, conquering the frontier, and a masculine brand of the American identity. Wenders has said that Paris, Texas is about men and women, and how their prescribed gender roles often prevent them from making meaningful connections and identifying with one another. That innate clashing, underscored by the title, contrasts two unique mythologies people hope to achieve. Travis has tried to conform to that masculine idea, adopting its violence and implied desire to conquer and control the family. He has tried to become Texas and enforce these ideals onto Jane, a Parisian archetype, but it resulted only in pain—the pain he caused Jane and, by extension, the pain he caused himself. Travis learns through the narrative that masculine and feminine roles, the romantic notions of Texas and Paris, inhabit mythologies—generalizations or broad frameworks of understanding. By the final scenes, he recognizes that people are more complicated than that.

Of course, the real-life Paris, Texas, exists in Lamar County, in the northeastern part of the state, and plays a referential role in the film. Travis shares a story with Walt, passed down from their father, that their parents first made love in Paris, and likely, Travis was conceived in the Texas town. It was their mother’s birthplace, which their father used to joke about, saying she was from “Paris,” at which point he would pause, allowing the listener to fill in the blank of France, only to add “Texas.” Eventually, their father’s “sickness” led to him pretending their “fancy” mother was from Paris, France. So when Travis and Jane were together, Travis purchased a plot of land in Paris, Texas, hoping to build a home and reconnect with the concept of what a family should be—a domineering male and a glamorous female. He carries a faded photograph of the plot with him, though the space is little more than dirt and gravel—a telling sign that Travis’ former view of a family and home, informed by patriarchal expectation, is empty and fruitless. The town and how the place informs his behavior with Jane consume Travis’ former self, so when he finally begins to emerge from his silence early in the film, “Paris” is his first word. But Travis must relearn what a family is with his new perspective. And so, Wenders structures the film around three sets of reunified family relationships: the renewed bond between siblings when Walt picks up his brother from Texas and returns him to Los Angeles; the father and son, Travis and Hunter, reconnecting in the second act; and the family, Jane and Hunter, coming together by the ending.

Among these, the brotherly bond might go overlooked, though it’s the relationship in which Shepard may have the most influence. The playwright already examined brotherly dynamics in his play True West. Walt remains a fascinating character because he represents a distributor of false ideas, the sort of romantic associations to which Travis clung in the past. Walt works as an advertiser, making large billboard signs in the city that invade the landscape. Wenders introduces him overseeing a trompe-l’œil skyscraper that quickly reveals itself as an ad, hinting at the film’s theme of the line between mythos and reality. Walt represents everything that Travis now rejects, his name a reference to Walt Disney, his cap branded with the Stetson logo (by contrast, Travis’ cap is plain, red, and austere), his domestic life rooted in the traditional dynamics that caused such a fissure between Travis and Jane. At the beginning of their relationship, Walt serves as a kind of father figure to Travis, buying his brother clothes, putting up with his tantrum on the plane, and driving him back to Los Angeles. Travis even sits in the back seat like a child, withdrawn and quiet in a “silent routine,” much to Walt’s annoyance. Gradually, Travis begins to emerge again, remembers how to speak, and only takes on the role of an adult after being confronted with Hunter and the home videos of his former self.

Among these, the brotherly bond might go overlooked, though it’s the relationship in which Shepard may have the most influence. The playwright already examined brotherly dynamics in his play True West. Walt remains a fascinating character because he represents a distributor of false ideas, the sort of romantic associations to which Travis clung in the past. Walt works as an advertiser, making large billboard signs in the city that invade the landscape. Wenders introduces him overseeing a trompe-l’œil skyscraper that quickly reveals itself as an ad, hinting at the film’s theme of the line between mythos and reality. Walt represents everything that Travis now rejects, his name a reference to Walt Disney, his cap branded with the Stetson logo (by contrast, Travis’ cap is plain, red, and austere), his domestic life rooted in the traditional dynamics that caused such a fissure between Travis and Jane. At the beginning of their relationship, Walt serves as a kind of father figure to Travis, buying his brother clothes, putting up with his tantrum on the plane, and driving him back to Los Angeles. Travis even sits in the back seat like a child, withdrawn and quiet in a “silent routine,” much to Walt’s annoyance. Gradually, Travis begins to emerge again, remembers how to speak, and only takes on the role of an adult after being confronted with Hunter and the home videos of his former self.

It’s as though Travis has been reborn and needs to relive his childhood under Walt before becoming Hunter’s father, a role he learns to play in amusing scenes with the help of Walt and Anne’s maid, Carmelita (Socorro Valdez)—she teaches him how to dress and walk the part. Similarly, Travis must re-learn domesticity by inhabiting Walt and Anne’s home and observing their behaviors, even as he remains uneasy in their company. Within the domestic sphere of Walt’s household, Anne’s presence remains fascinating and more complex than a mere homemaker. A Frenchwoman, she embodies Travis and Walt’s father’s ideal for his Parisian wife, a nod toward the title’s romantic cultural illusion, which Walt, who surrounds himself with artificial billboards and corporate logos, has fulfilled. However, her roles as wife and mother are questioned, or at least tested, by Travis’ return and reclamation of Hunter—a movement to restore Travis’ family but a collapse of the billboard-like artificiality of Walt and Anne’s. She seems to recognize more than Walt how their marriage hangs by the thread of Hunter’s presence, allowing them to carry on the charade. It’s no wonder that when Travis and Hunter take to the road to find Jane, Walt and Anne all but disappear from the film, apart from Hunter’s brief call home to explain their trip.

The scenes between Travis and Hunter show a cute and endearing bond, though Travis’ slow adoption of his fatherly role necessitates Hunter to guide him through the vastness of the landscape. A spiritual and geographical navigator, the Star Wars and NASA-obsessed child shares facts about the limitlessness of space and time, yet he offers direction to Travis more than once. “Left, Dad,” says Hunter when Travis finds himself at a literal crossroads. Moreover, Wenders and Müller often situate Hunter in the center of a shot or a position of authority next to the recessive Travis; one scene even features Travis lying down on a couch while Hunter sits next to him in a chair, mirroring the analyst-patient dynamic. Still, Travis never fully returns to his role as Hunter’s father, nor does he confront his failures as a father with Hunter. Their journey to Houston is bittersweet in that sense. Wenders hints at the possibility of something more between them, but Travis proves childlike and inadequate for the conventional roles of father and husband. Even though he restores himself to adulthood by recounting to Jane the failures of their marriage, how he tied a cowbell to her and chained her to the stove, he cannot restore himself to Hunter and Jane once they are reunited. He remains at a remove, both literally in the sense that he keeps himself at a distance from Jane in the parlor, and figuratively in that the ideas of the family and their images in the home video are unreal to Travis. His guilt and shame over his past actions and his understanding of his limitations as a human being lead to Travis becoming whole by recognizing his prescribed role in the patriarchal family and removing himself from it so as not to repeat past traumas.

Travis’ new beginning is hopeful but rather tragic in its solitude. Few actors could capture the character’s heroic yet aching willingness to remove himself from the domestic space as the then 58-year-old Stanton, who called Paris, Texas his favorite of his performances. Before Wenders cast him as the lead, Stanton had spent over a quarter-century playing minor roles in iconic Hollywood films. You see him as the folk-singing prisoner in Cool Hand Luke (1967) or a rugged cowboy in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garret and Billy the Kid (1973). He made his mark in genre films with memorable turns in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981), and Christine (1983). He would go on to work with masters from Martin Scorsese to David Lynch to Terry Gilliam, though rarely did he play the lead. But his long, weathered face and wounded eyes could never have been replicated by another actor, nor could Travis’ determined walk and eager, desperate looks toward the horizon in the first scenes. Opposite him, Wenders cast Kinski, the German actress he discovered for a role in his 1975 feature Wrong Move. Though her role in Paris, Texas may seem limited, her character’s presence throughout the film is deeply felt on Stanton’s face. However, upon reflection, perhaps Wenders and his writers too easily pigeonhole Jane in the Freudian mother-whore stereotype for a film asking questions about gender roles.

The other major star of Paris, Texas is Wenders’ longtime collaborator Robby Müller, the Dutch cinematographer whose approach never calls attention to itself yet finds painterly beauty in natural light, expansive compositions, and cityscapes. Besides his long collaboration with Wenders, which includes the Road Trilogy, The American Friend (1977), Until the End of the World (1991), and others, Müller worked repeatedly with Jim Jarmusch and shot some of the best films by William Friedkin (To Live and Die in L.A., 1985), Lars Von Trier (Breaking the Waves, 1996), and Michael Winterbottom (24 Hour Party People, 2002). But his partnership with Wenders remains central, calling attention to the vastness of the open road and philosophical underpinnings of the director’s work. “My stories start with places, cities, landscapes, and roads,” said Wenders, and Müller captures characters within these surroundings, accented by road signs, street lights, and skyscrapers that reflect the symbolic yet often broken-down worldview Travis maintains after returning to civilization. A recurring visual motif in the film finds Müller observing fiery sunsets that give way to the artificial hum of fluorescent lights, an apt metaphor for the burning inside of Travis that rejects the falsely glowing pretense of the gender roles in the traditional American family.

From Stanton’s initial appearance in the desert, walking purposefully toward his reconciliation, albeit almost unconsciously, to the final moment when Travis leaves his wife and son and then sets on the road for a new beginning, Paris, Texas feels rooted in movement. It is a movement away from the patriarchal traditions of the American myth, which were reinforced in the 1980s by Reaganism and increased conservatism, even though the on-the-road setting brings to mind American literature from John Steinbeck to Jack Kerouac. It is an assessment and critique of those American mythologies. Still, it is also a wholly American piece of storytelling in that the country’s ethos is rooted in self-discovery and redefinition. Then again, Wenders underscores that themes so often associated with American storytelling have been instilled in his European projects, suggesting the ideas behind Paris, Texas may be more universal than they seem. Beyond its philosophical, psychological, and ideological implications, Wenders and Shepard tell a story that shreds the emotions, leaving the viewer as raw and wounded as Travis, if also as hopeful as his faint smile as he sets out, away from his wife and child, to reconcile with himself.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on August 30, 2023. Many thanks for your continued patronage and support, Mark!)

Bibliography:

Carson, L. M. Kit. “Dejeuner Diary: Postcards from the Old Man on Paris, Texas.” Film Comment, vol. 20, no. 3, 1984, pp. 60–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43452964. Accessed 11 Aug. 2023.

Carveth, Donald. L. “The Borderline Dilemma in ‘Paris, Texas’: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Sam Shepard.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. 25, no. 4, 1992, pp. 99–120. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24780558. Accessed 11 Aug. 2023.

Dieckmann, Katherine, and Wim Wenders. “Wim Wenders: An Interview.” Film Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 1984, pp. 2–7. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212216. Accessed 17 Aug. 2023.

Graf, Alexander. The Cinema of Wim Wenders: The Celluloid Highway. Wallflower Press, 2002.

Kolker, Robert Phillip and Peter Beicken. The Films of Wim Wenders: Cinema as Vision and Desire. Cambridge Film Classics. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Luprecht, Mark. “Freud at ‘Paris, Texas’: Penetrating the Oedipal Sub-Text.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 2, 1992, pp. 115–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43797642. Accessed 11 Aug. 2023.

Mariniello, Silvestra, and James Cisneros. “Experience and Memory in the Films of Wim Wenders.” SubStance, vol. 34, no. 1, 2005, pp. 159–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3685625. Accessed 17 Aug. 2023.

Smith, Roch C. “Open Narrative in Robbe-Grillet’s ‘Glissements Progressifs Du Plaisir’ and Wim Wenders’s ‘Paris, Texas.’” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 1, 1995, pp. 32–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43798709. Accessed 11 Aug. 2023.

Wenders, Wim. “Melinda Camber Porter in Conversation with Wim Wenders: On Set of Paris, Texas 1983.” Interview by Melinda Camber Porter. Audible. Author’s Republic, 2017.

—. The Logic of Images. Essays and Conversations. Trans. Michael Hoffman. Faber & Faber, 1991.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review