The Definitives

Our Man in Havana (1959)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In 1950s cinema, filmmakers commented on the Cold War predominantly through allegory and allusion. Hollywood “B” movies perpetuated Soviet, political, and nuclear paranoia with creature features concerned with what Susan Sontag called “the aesthetics of devastation”—warped colossal insects and monsters crawling with atomic anxiety, or pod people taking over our minds and bodies. In the 1960s, however, spy stories about cloak-and-dagger agents, international conspiracies, foreign secrets, and acts of espionage saturated popular entertainment, from James Bond to The Manchurian Candidate (1962). As ever, author Graham Greene was ahead of the political curve. He wrote the comic intrigue of Our Man in Havana in 1958, and rather than approaching it with a seriousness befitting the potential global consequences or more attuned to the works of John le Carré and Ken Follett, Greene’s book cut into the potential for absurdity in modern espionage. Director Carol Reed’s version of Greene’s story involves Alec Guinness as a British expatriate in Cuba who takes advantage of his government’s desire for fresh intelligence by fabricating a deadly political conspiracy. What begins as another of Reed’s acerbic, ironic, and thoroughly readable tales gives way to a shadowy satire in which nationalism presents the greatest danger and intelligence is a generous term.

Reed collaborated with Greene for the third time on Our Man in Havana, having rushed to buy the book’s film rights not long after its publication. Greene had originally outlined the material for Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti, basing the story, about a spy who fabricates mission reports back to his trusting controllers, on real-life experience. When Greene served the British Secret Service in Portugal in the mid-1940s, he witnessed spies doing that very thing. His original idea for the story involved a British spy during World War II sending false reports from Estonia, but the concept was scrapped after Cavalcanti voiced concerns about ridiculing the Secret Service, especially during such a serious moral war. Audiences would hardly accept an Allied spy making light of the war against Nazis. “The reader could feel no sympathy for a man who was cheating his country in Hitler’s day,” Greene observed. “However, in fantastic Havana, among the absurdities of the Cold War… There was a situation allowably comic.” Such remarks point to the changing landscape and uncertainty of the Cold War that, from a place of moral and national uncertainty, paranoia, and fear, could only be met with the black humor of films like Our Man in Havana or, five years later, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Indeed, Our Man in Havana predates Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War satire with an ambiguous, smaller scale and character-driven mockery of espionage. In securing the book’s rights, Reed narrowly undercut Alfred Hitchcock, who, understandably, was attracted to the material’s combination of dry humor and spy machinations—qualities that defined much of Hitchcock’s output. Greene was pleased to be working with Reed again rather than the so-called Master of Suspense, having nothing but dismissive views toward Hitchcock’s films that, he wrote, “lead to nothing” from all their amusing situations and “inadequate sense of reality.” Reed had set up his own production company, Kingsmead Productions, and shopped the property around Hollywood, eventually settling with Columbia Pictures. Due to costs, the studio gave Reed two options: shoot in Spain using color film stock or on-location in Cuba using black-and-white footage. Seeking authenticity for his film, Reed resolved to stage the production in Cuba, enlisting John Huston’s frequent cinematographer Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, The Man Who Would be King) to shoot in CinemaScope.

Indeed, Our Man in Havana predates Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War satire with an ambiguous, smaller scale and character-driven mockery of espionage. In securing the book’s rights, Reed narrowly undercut Alfred Hitchcock, who, understandably, was attracted to the material’s combination of dry humor and spy machinations—qualities that defined much of Hitchcock’s output. Greene was pleased to be working with Reed again rather than the so-called Master of Suspense, having nothing but dismissive views toward Hitchcock’s films that, he wrote, “lead to nothing” from all their amusing situations and “inadequate sense of reality.” Reed had set up his own production company, Kingsmead Productions, and shopped the property around Hollywood, eventually settling with Columbia Pictures. Due to costs, the studio gave Reed two options: shoot in Spain using color film stock or on-location in Cuba using black-and-white footage. Seeking authenticity for his film, Reed resolved to stage the production in Cuba, enlisting John Huston’s frequent cinematographer Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, The Man Who Would be King) to shoot in CinemaScope.

Set in Fulgencio Batista’s pre-revolutionary Cuba, the film adopts a familiar Greene setting that places the outsider-hero in a foreign backdrop of political turmoil, where his identity is tested by the local culture and ideology. Such is the case with Holly Martens who, in the Reed-Greene masterpiece The Third Man (1949), arrives in the bombed-out postwar Vienna to find his ideals rocked by the corruption of the local black market. Or their film The Fallen Idol (1948), where the French ambassador’s son adores the British butler’s tales of colonial heroism to their mutual disadvantage. Greene’s strain of political cynicism and anti-imperialism was apt for the period. After the devastating effects of World War II, the former might of England’s imperialist influence had begun to decline; the British concentrated less and less on their colonies in Africa and Asia. Along with blows to England’s status as a world power, such as the Suez Crisis, many British colonies nationalized and eventually turned into independent countries. Greene’s novel fully embraces the decline unlike, say, the spy novels of Ian Fleming, which maintained the authority of the British through their hero James Bond. Greene’s novel of Our Man in Havana considers the decline of British influence against the changing tides of Cuban politics and culture, challenging the ingrained British dominance and authority with an unmistakable air of mockery. Conveniently enough, not long after production began, Batista was overthrown, a detail that further accentuates the volatile period in which the film is set.

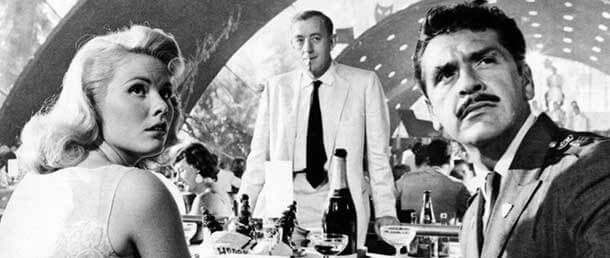

Fortunately, in his travels, Greene befriended the revolution’s leader Fidel Castro, whose visit to the set on one occasion did not altogether protect the production from the watchful eye of the new government. Cuban ministers demanded the screenplay to be translated into Spanish to ensure the material portrayed Cuba in a positive light. While both Reed and Greene held Cuba in the utmost fondness, their appreciation for the lively surroundings and nightlife was not blind to the potential for squalor and seediness. Accordingly, Greene’s screenplay explores the winding roads and cramped buildings in Old Havana, crowded with shops, hotels, corner bars, packed streets, strip joints, and nightclubs—locations teeming with tropical sexuality. The film’s central would-be spy, the British citizen and vacuum cleaner salesman Jim Wormold (Guinness), enjoys regular injections of daiquiris (which he pronounces “die-queries”). His fellow salesman, Lopez (Joseph G. Prieto), doubles as a pimp and throughout the film, due to a misunderstanding, keeps offering photos of prostitutes that Wormold must decline. But Reed also explores the old regime’s classist country clubs and ritzy locations that define how the local Hispanic culture had been redefined through political authoritarianism and sexuality. It’s a notion thoughtfully juxtaposed over the title sequence, as a bikini-clad woman swims in a pool monitored by a policeman, reflecting Cuba’s pre-revolutionary culture—what Reed scholar Peter William Evans called a “whorehouse of sexual tourism”—corrupted by capitalistic influence and political interference, primarily from the United States. Additionally, Captain Segura, the film’s villain nicknamed “the Red Vulture,” was based on Esteban Ventura Novo, the feared and hated chief of police in Havana during the Batista regime. Ventura fled Cuba when Castro took over, moving to Miami and leaving behind a reputation that linked him with several political murders and torture of so-called enemies of the state. The Cuban government didn’t want a Ventura-like character portrayed with human qualities, and so Segura carries a wallet made of human skin and openly admits to using torture.

Among the film’s litany of early images portraying Havana’s urban sprawl as a sexualized paradise comes the appearance of a sore thumb donning a black suit and carrying an umbrella—Hawthorne (Noël Coward), a bastion of Anglo-Saxon otherness beset against the vivid contrasts of sexuality and authority on the streets in Cuba, is further marked by Frank and Laurence Deniz’s score of Latin and jazz touches. Hawthorne serves as the British handler of spies in the territory, and his inability to blend in should tell us something about the character’s skill as an agent. Along with his superior in Whitehall, known only as “C” (Ralph Richardson), Hawthorne clings to his country’s colonialist authority using techniques that no longer work in a world shaped by selfish motivations. Notions of duty and devotion to the motherland remain their central concern. Although, given the changing tides of international imperialist power, watching Our Man in Havana today, or even upon its release after the revolution, makes the British aims look all the more in vain, if not historically ironic. To be sure, it’s any wonder why Hawthorne thinks Wormold will make an effective spy. He enters Wormold’s vacuum cleaner shop and is asked whether he’s looking for a vacuum. “In a way,” replies the veteran agent, not realizing that the kind of vacuum he has found isn’t the impenetrable, strong-minded cipher he needs, but rather a soft everyman who looks positively baffled when trying to demonstrate his own product.

Though Wormold struggles to reassemble the floor model vacuum, he’s not so dim that he lacks dimension. Guinness wanted to play Wormold with more obvious and readable characteristics, such as an untidy appearance and general air of ineptitude, but Reed wanted the character to be more complicated than the first impression. According to the director’s biographer Nicholas Wapshott, Reed told the actor, “We don’t want any of your character acting. Play it straight. Don’t act.” Sure enough, Guinness bore a quality that made him innately inscrutable and multidimensional, with the similar sense of mystery and fascination he brought to his myriad of characters in Kind Hearts and Coronet (1949) and Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), or his rendering of George Smiley in British television’s 1979 adaptation of le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Greene’s writing of Wormold sketches out a somewhat dim figure that is more byzantine and far less innocent than he initially appears, feeding Guinness’ strengths as an actor. An Englishman who has chosen to live in Latin America, Wormold is a Protestant with no strong religious ties; he was married to a Catholic woman who abandoned her family. He’s a generous father to his materialistic daughter, Milly (Jo Morrow), and his plans for her future include a Swiss finishing school, followed by marriage to a respectable Anglo husband. As the plot unfolds, it becomes apparent, quite essentially so, that he’s also a romantic and a daydreamer with a vivid imagination, which facilitates his outward innocence transforming him into a deceptive solo agent capable of murder.

Though Wormold struggles to reassemble the floor model vacuum, he’s not so dim that he lacks dimension. Guinness wanted to play Wormold with more obvious and readable characteristics, such as an untidy appearance and general air of ineptitude, but Reed wanted the character to be more complicated than the first impression. According to the director’s biographer Nicholas Wapshott, Reed told the actor, “We don’t want any of your character acting. Play it straight. Don’t act.” Sure enough, Guinness bore a quality that made him innately inscrutable and multidimensional, with the similar sense of mystery and fascination he brought to his myriad of characters in Kind Hearts and Coronet (1949) and Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), or his rendering of George Smiley in British television’s 1979 adaptation of le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Greene’s writing of Wormold sketches out a somewhat dim figure that is more byzantine and far less innocent than he initially appears, feeding Guinness’ strengths as an actor. An Englishman who has chosen to live in Latin America, Wormold is a Protestant with no strong religious ties; he was married to a Catholic woman who abandoned her family. He’s a generous father to his materialistic daughter, Milly (Jo Morrow), and his plans for her future include a Swiss finishing school, followed by marriage to a respectable Anglo husband. As the plot unfolds, it becomes apparent, quite essentially so, that he’s also a romantic and a daydreamer with a vivid imagination, which facilitates his outward innocence transforming him into a deceptive solo agent capable of murder.

Despite appearances, Hawthorne is more than a typically icy British spy bound to duty. Evans argues that Hawthorne is coded with homosexuality, which may, of course, be true, although the association seems to stem from an extratextual link between Coward’s homosexuality and the character he plays. When Hawthorne finds Wormold in a bar shortly after their initial meeting in the vacuum cleaner shop, their exchange develops with a humorous implication—Hawthorne engages in a conversation that Wormold doesn’t understand. “A bar’s not a bad place,” says Hawthorne. “You run into a fellow countryman, have a little get-together. What could be more natural? …Where’s the Gents? …You go in there and I’ll follow.” The proposition becomes clearer in the restroom when Wormold reluctantly follows, and Hawthorne offers to pay $150 tax-free to enlist his services: “We have to have our man in Havana.” Later, during Hawthorne’s shorthand explanation of spy tactics, a crash course in Espionage 101, it’s evident that Wormold doesn’t understand book codes, how to acquire a web of informants, or what his objectives should be, but Hawthorne continues nonetheless. As ineffective a spy as Wormold will prove, one cannot help but judge Hawthorne just as harshly for choosing him. Even “C” tells Hawthorne, “I was told once you were no judge of men, but I backed my private judgment.”

Though Milly calls her father “invincibly ignorant,” there’s something fascinating and intricate about Wormold, a man who exists isolated in his own imagination. He’s drawn to performance and fancy, and he impersonates Hawthorne after their meeting. Regarding himself in the mirror, Wormold does his best impression of Hawthorne. “Tax a-free!” He seems to drift into a spy fantasy unfolding in his mind, while Milly, herself daydreaming of country clubs and horseback riding, half-listens. “We should all be clowns,” he tells Milly in a melancholy tone. Wormold’s identification with clowns remains important to understanding the character. Beyond the performative aspect of clowns, which Wormold admires and reflects, clowns often represent a mockery of class from the bottom up—here, a thumbed nose at superior world governments with their international spies and state secrets. Wormold the clown imbues himself with an outside morality befitting the attitude of the film and its authors by treating officials and governments without serious consideration. When he tells his friend, Dr. Hasselbacher (Burl Ives), a wise and sad German expatriate who left his country in 1934, about his new position as a British agent, Hasselbacher offers advice: “As long as you invent, you do no harm.” Already drifting in his own headspace and an excessive drinker (qualities that led to his wife’s departure, we can imagine), he now indulges that headspace through the imagination required to be a spy. Wormold almost believes his own lies, and when he sees people in public that he’s told lies about, much to their confusion, he behaves as though his fantasy is real.

Wormold’s daughter also remains a source of humor and curiosity throughout the film. Spoiled by her father, Milly is a manipulative, albeit a doe-eyed version of Veruca Salt, with a hint of psychopathy. She’s a developed young woman (Morrow was 19 during the shoot), such that when Wormold hears men whistling, he knows his daughter must be around. Her fair-haired, American-accented presence in Cuba stands out, drawing the attention of Segura—and she encourages the Red Vulture’s advances, despite her father’s warnings. “I know, he tortures prisoners. But he never touches me,” she says of the Captain, which is of no comfort to her father. Then again, Segura might just be the latest in her string of flirtations with disaster. Wormold makes allusions to an incident when Milly was 13-years-old and she set a young man on fire (“They had to push him in the fountain to put him out”), suggesting that Milly may have the same penchant for torture as Segura. After all, she’s aware of Segura’s violent reputation, but his ability to appease her materialism remains above all else. The film’s plot rests on Wormold’s desire to make his daughter, his only family member, happy. As such, almost immediately after starting his position for Hawthorne, he buys Milly the horse she wants and a country club membership where she can ride, thinking little of how the purchases will look on the reports to Hawthorne.

To afford Milly’s happiness, Wormold fabricates agents and falsifies reports with stories about a pilot named Montez—a fictional flier for Cubana Airlines who Wormold claims provided detailed sketches of a secret Cuban installation in the snow-covered mountains, which of course Wormold sketched himself. “But there’s no snow in Cuba,” he’s warned. “They won’t know that,” Wormold replies, drawing the fictional installation to resemble parts from one of the vacuum cleaners he sells in his shop. Hawthorne notices the resemblance between the sketches and a vacuum, but he and others at Whitehall remain convinced by Wormold’s performance, declaring, “we may be onto something so big that the H-bomb will become a conventional weapon.” They send Wormold more experienced agents to assist him, including a secretary, Beatrice (Maureen O’Hara), who’s eventually a love interest for Wormold. Regardless of his fiction, Wormold’s findings, although invented, lead to suspicious behavior, suggesting that Segura and the Cuban government may be hiding something. The reports to his superiors are intercepted by enemy spies and, as it turns out, an actual pilot named Montez is murdered. The worst paranoia and most convoluted lies reveal an actual conspiracy, making Wormold the target of unknown forces.

An enemy agent named Carter (Paul Rogers), posing as a fellow vacuum salesman, tries to poison Wormold at an industry conference luncheon, allowing for Reed to build a superb scene using an animal—much in the same way he introduced Harry Lime in The Third Man with a kitten or formed a tragedy around the boy in The Fallen Idol with the demise of a pet snake. Wormold’s whiskey has been poisoned and, knowing this, he intentionally drops the glass onto the floor, where a small dachshund drinks it and dies suddenly with a harsh yelp. Wormold avoids being a target, but the secret organization backing Carter responds by killing Hassellbacher, their informant. Finally, Wormold’s impersonation of Hawthorne becomes so expertly observed that he develops an agent’s instinct to kill. To secure himself a gun, he challenges Segura to a game of checkers—what Hassellbacher refers to as a dull game played by fools, but hilariously, it’s the only game Segura and Wormold play. Wormold suggests a twist: every capture requires the victor to drink a miniature bottle of liquor. Wormold, being a talented drinker, throws the game, gets the gun from a passed-out Segura, and makes short work of Carter. Wormold has killed Carter like a good agent, and for all the reasons British Intelligence would protest against, from revenge to the continued prosperity of his personal life.

In the final scenes, Wormold, whose lies have been exposed by his controllers, finds himself promoted rather than imprisoned for his deceptions. Despite Whitehall’s awareness of his lies, they cannot admit to their being deceived without looking foolish and weak, and so they give him a position teaching up-and-coming spies, commending his actions and tactics. It’s an absurdist turn that Joel and Ethan Coen would echo in Burn After Reading (2008), a similar spy yarn populated with nothing but inept and baffled characters. But from a historical context, Our Man in Havana remains a singularly prophetic story and, only with considerable distance, quite funny. Over the next two years, world powers including the United States and the Soviet Union vied for control over Cuba. Castro was committed to fighting imperialist influence from the U.S. and sought the protection of the Soviets through weapons and soldiers, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Reed and Greene’s film predicted what would become secret missile installations, clandestine actions against Western influence, and the threat of international consequences—reflecting what in 1962 would become no laughing matter. Perhaps as a result, Our Man in Havana remained rather undiscussed for decades, while today it deserves recognition for its wit and foresight.

In the final scenes, Wormold, whose lies have been exposed by his controllers, finds himself promoted rather than imprisoned for his deceptions. Despite Whitehall’s awareness of his lies, they cannot admit to their being deceived without looking foolish and weak, and so they give him a position teaching up-and-coming spies, commending his actions and tactics. It’s an absurdist turn that Joel and Ethan Coen would echo in Burn After Reading (2008), a similar spy yarn populated with nothing but inept and baffled characters. But from a historical context, Our Man in Havana remains a singularly prophetic story and, only with considerable distance, quite funny. Over the next two years, world powers including the United States and the Soviet Union vied for control over Cuba. Castro was committed to fighting imperialist influence from the U.S. and sought the protection of the Soviets through weapons and soldiers, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Reed and Greene’s film predicted what would become secret missile installations, clandestine actions against Western influence, and the threat of international consequences—reflecting what in 1962 would become no laughing matter. Perhaps as a result, Our Man in Havana remained rather undiscussed for decades, while today it deserves recognition for its wit and foresight.

Although, in the end, Wormold, Milly, and Beatrice receive protection in the spy ranks of England, our hero never devolves into a good Englishman. He subsists without remorse or responsibility to his nation, only a detached self-preservation and love for his daughter and rather underdeveloped lover, while his security is assured by the bruised ego of those in Whitehall. Greene’s skepticism toward devout Englishness, or any other brand of nationalism, defines Our Man in Havana, along with the author’s other collaborations with Reed. More than the escapist Cold War actioners, featuring the debonair James Bond single-handedly thwarting schemes and defending England, and Western values the world over, Reed’s film anticipates the fervent national loyalties to come. He sees them from an outsider’s perspective, where humanism and imagination seem like trivialities next to such intrigue. But as Wormold remarks at one point, “Would everything be in the mess it is if we were loyal to love and not to countries?”

Bibliography:

Durgnat, Raymond. A Mirror for England: British Movies from Austerity to Affluence. Praeger, 1971.

Evans, Peter William. Carol Reed. British Film Makers. Manchester University Press, 2005.

Greene, Graham, and John Russell Taylor (Editor). The Pleasure Dome – Graham Greene: The Collected Film Criticism, 1935-40. Oxford University Press, 1987.

Moss, Robert F. The Films of Carol Reed. Columbia University Press, 1987.

Samuels, Charles Thomas. Encountering Directors: Interviews. Capricorn Books, 1972.

Sontag, Susan. “The Imagination of Disaster.” Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Picador, 1961.

Wapshott, Nicholas. A Man Between: A Biography of Carol Reed. Chatto & Windus, 1990.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review