The Definitives

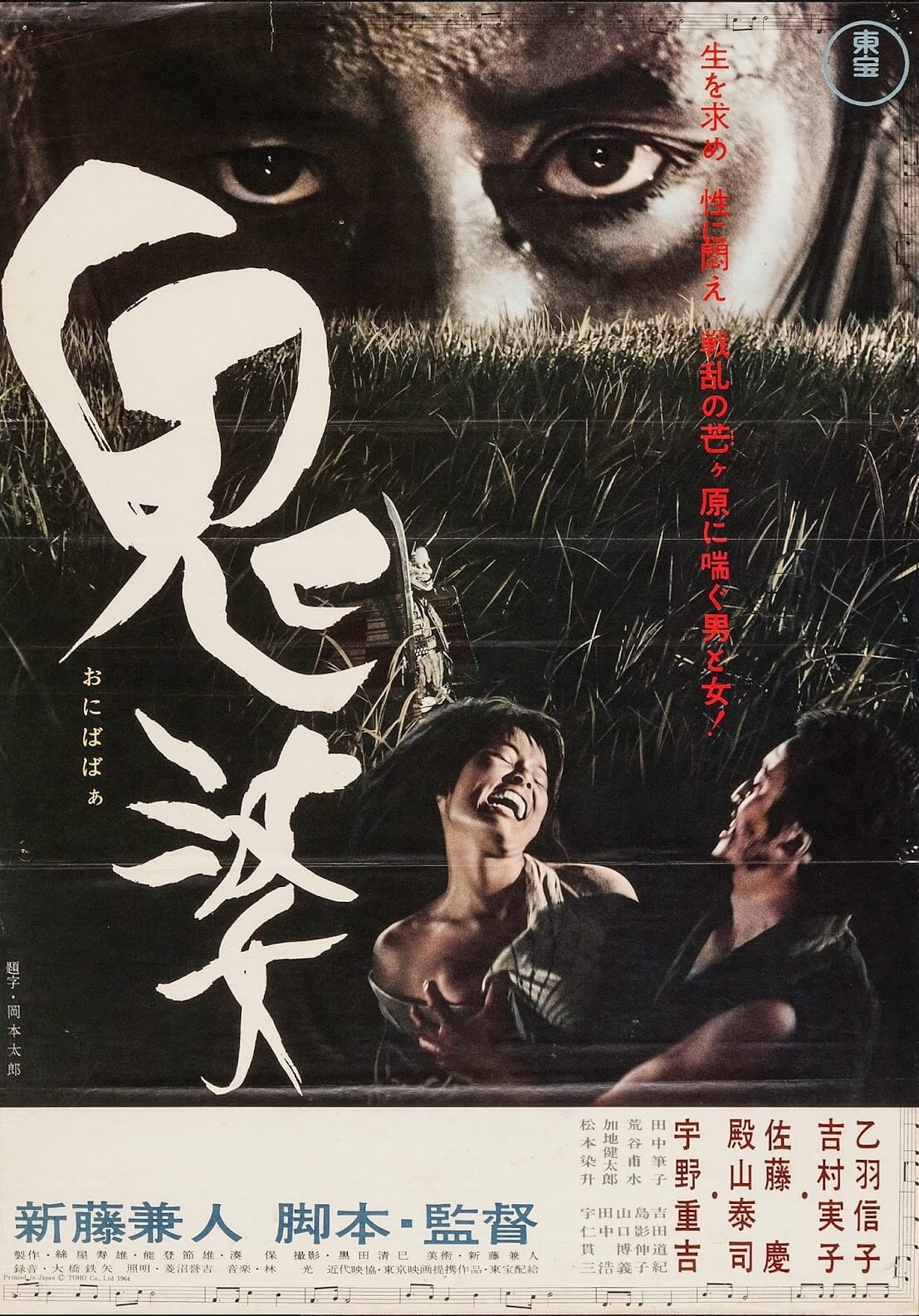

Onibaba (1964)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Two desperate, battle-worn samurai evade their pursuers in a thick marsh. They hunker down, keeping out of sight in the tall reeds until the men on horseback give up their chase. After catching his breath, one of the samurai checks on his comrade. At that same moment, two spears plunge from the thick foliage into the samurai, spraying blood on the reeds. The women behind the spears emerge from the wall of grasses and check for any signs of life in their prey. With the samurai dead, the older woman and her daughter-in-law begin to remove the armor and weapons from their victims. They drag the corpses through the reeds to a pit, an abyss whose “darkness has lasted since ancient times,” and while the only witnesses to this murder are the ravens on a nearby perch, the abyss seems to look back at the murderesses. A fable of sexuality, violence, and survival, Onibaba has a rich, if obscured, vein of political fury, though it’s remembered more for its supernatural elements. Kaneto Shindo, a member of the Japanese New Wave cinema movement of the 1960s, was often thought to be a director who told stories about women enduring the feudal institutions of Medieval Japan. But Onibaba uses a mixture of realism and folklore, lust and horror, to disentangle nuclear-era contexts in a postmodern approach. Its convergence of cinematic style and sweaty desolation, marked by the presence of a haunting mask, leads to an unforgettable climax that permanently fixes a place in the viewer’s mind.

Born in 1912, Shindo, who died at the age of 100, retains a reputation in the West primarily for his horror films, while his work after the 1960s has barely been seen outside of Japan, despite his most recent release, Postcard, debuting in 2010. Before directing more than forty films and writing more than two hundred screenplays, Shindo began his career in the Japanese film industry as a set designer and co-director, having collaborated with Kenji Mizoguchi on the 1941 human epic The 47 Ronin (more than thirty years later, Shindo made the documentary Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director about his mentor). He finally made his directorial debut for Daiei Studios with Story of a Beloved Wife in 1951, a fictionalized account of his first wife’s death. But he quickly moved away from the studio system and developed his own production company to tell stories that many official channels deemed unpopular topics for cinema: Children of the Atom Bomb (1952) tackled the aftereffects of the Hiroshima bombing; and Lucky Dragon No. 5 (1959) told the true story of the fishermen exposed to fallout after a U.S. nuclear test at Bikini Atoll—the same unpopular subject matter that inspired 1954’s Godzilla, but without the benefit of a colossal iguana. Shindo sought a social realism and activism in his films of the 1950s and early 1960s, his most famous example being The Naked Island (1960), his entirely dialogue-free ethnographic observation about a small community in the Inland Sea. He also explored subjects such as poverty, drugs, prostitution, environmental concerns, and corruption, usually in a modern setting.

Onibaba was released during the Japanese New Wave, a movement intentionally modeled after France’s Nouvelle Vague. Driven by renegade filmmakers who addressed historical, social, and political issues in Japan, the movement came about in the decade after the U.S. Occupation ended. Unimpeded by the Occupation’s censors, directors could finally explore the war’s consequences, above all the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended the Second World War in the Far East. Shindo belongs among other filmmakers of this movement—Nagisa Oshima (Death by Hanging, 1968), Hiroshi Teshigahara (Woman in the Dunes, 1964), Shohei Imamura (The Pornographers, 1966), and Kon Ichikawa (An Actor’s Revenge, 1963)—in his use of traditional genres and styles to tell stories that remark on the postwar effects of the U.S. nuclear attack. But the films were far from conventional in their execution. Shindo and his contemporaries developed a New Wave from a playful mixture of traditional styles, combining and repurposing them into a postmodern format that, as Japanese film scholar Donald Richie observed, “bravely attacked a prevailing materialistic social philosophy” and addressed the “cynicism and corruption of the world.” Moreover, films of the Japanese New Wave also developed a prevailing focus on women. Of course, filmmakers such as Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu considered women long before the New Wave, but Shindo and his contemporaries investigated how women were forced to use sex as a way to survive impossible conditions.

Onibaba was released during the Japanese New Wave, a movement intentionally modeled after France’s Nouvelle Vague. Driven by renegade filmmakers who addressed historical, social, and political issues in Japan, the movement came about in the decade after the U.S. Occupation ended. Unimpeded by the Occupation’s censors, directors could finally explore the war’s consequences, above all the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended the Second World War in the Far East. Shindo belongs among other filmmakers of this movement—Nagisa Oshima (Death by Hanging, 1968), Hiroshi Teshigahara (Woman in the Dunes, 1964), Shohei Imamura (The Pornographers, 1966), and Kon Ichikawa (An Actor’s Revenge, 1963)—in his use of traditional genres and styles to tell stories that remark on the postwar effects of the U.S. nuclear attack. But the films were far from conventional in their execution. Shindo and his contemporaries developed a New Wave from a playful mixture of traditional styles, combining and repurposing them into a postmodern format that, as Japanese film scholar Donald Richie observed, “bravely attacked a prevailing materialistic social philosophy” and addressed the “cynicism and corruption of the world.” Moreover, films of the Japanese New Wave also developed a prevailing focus on women. Of course, filmmakers such as Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu considered women long before the New Wave, but Shindo and his contemporaries investigated how women were forced to use sex as a way to survive impossible conditions.

Shot on location during a hot summer on the eastern edge of Tokyo in the Inba Marsh, Onibaba concerns bottom feeders. The unnamed older woman (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura) have carved out a living, but not by sleeping with men in a brothel, as many women did during this period; rather, they eke out a living by preying on samurai unfortunate enough to sink into their territory. Shindo emphasizes this theme with their loose robes that hang off their bodies and offer brief glimpses of their grimy, naked flesh. The old woman dons a robe with a crab decorated on the back; the daughter’s robe features a scallop. Both aquatic creatures find their sustenance by consuming the muck and microbes that fall to the bottom, and Shindo undoubtedly chose these animals to reflect his characters. The women have reverted to an animalistic state, killing and jealously shoveling food into their mouths when they have it, from bits of rice to an unfortunate stray dog. They are scavengers, not unlike the ravens that linger near the women throughout the film. Shindo admits that with Onibaba, he “wanted to convey the lives of down-to-earth people who have to live like weeds.” The women of the film, surrounded by windswept reeds, recall the farmers from Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), who seem innocent enough until one of the warriors hired to protect their village from bandits discovers their secret: they have murdered samurai for their wares in the past. But unlike the farmers in Kurosawa’s film, the women of Onibaba have lost any hope of redemption; murder is the only way they know how to survive.

Their way of life depends on a partnership; they need each other to help attack and dispose of samurai who wander into the reeds. The film’s narrative centers on the older woman trying to preserve that coexistence, thus their survival. Everything else—human dignity, emotional connections, social graces—is secondary. But Ushi (Taiji Tonoyama), a cave-dwelling merchant who buys samurai armor and weapons, informs the women of the Emperor fleeing Kyoto to Mount Yoshino. While this may signal an end to the conflict that caused the women to become killers in the first place, it also means “no more big skirmishes” will supply lifegiving samurai. Another threat arrives with Hachi (Kei Sato), a neighbor who went off to war with their son and husband, Kishi, who they learn has been killed—beaten to death, coincidentally enough, by farmers trying to protect themselves from soldiers. In Kishi’s place, Hachi sniffs after the new widow, and she responds by encouraging his gaze. Kishi’s mother disapproves of their coupling; then again, perhaps her disapproval is pure jealousy, as she attempts to secure the younger man for herself to no avail when she confronts him with a breast unashamedly exposed. Such sexual yearning pulses through the film and scratches at its characters. Hachi, having been away at war for a long time and now unable to take his friend’s widow, writhes in the grasses out of sexual frustration in an almost childlike tantrum. The old woman has a similar reaction when Hachi rejects her; she pushes herself against a tree to satiate her desire.

A persistent theme in Shindo’s films starting in the 1960s is his concentration on sexuality’s place in our everyday lives; specifically, the spectrum of female sexuality, ranging from love to the use of sex as a weapon. “Our human existence is rooted in sex,” Shindo said. “Though conservatives reject the very idea as dangerous, I would say the way to save us from our own perversity is by confronting sex courageously.” Onibaba was the first of his sexually confronting films, leading to a string of works set during Japan’s feudal period that involve women defined by their sexual objectification as the subjects of desire, obsession, rape, and ultimately death. His first feature after Onibaba was Akuto from 1965, about a courtier who wants a woman so badly that he arranges for the death of her loved ones so that he can have her all for himself. In the chilling conclusion, a servant presents the eerily smiling, decapitated head of the obscure object of desire to the courtier. Another film set in the feudal period, Kuroneko from 1968, closely mirrors Onibaba, following an older woman and a daughter-in-law who are raped and murdered by roving samurai. In the aftermath, the women come back as ghosts, ushered by a black cat spirit—they have sold their souls in exchange for the opportunity to seduce, murder, and drink samurai blood for the rest of eternity. Scholar Keiko I. McDonald noted that Shindo’s female characters are often “paragons of sexuality gone awry, especially female sexuality.” But McDonald also remarked that Shindo viewed sexuality as inseparable from survival; it is an essential part of being human. This theme continues throughout his career, evidenced as recently as Shindo’s The Owl from 2003, about a mother-daughter pair of prostitutes who resort to murder to survive. As for Onibaba, its trio of characters have suppressed their sexuality to ensure their basic survival for so long that all else seems secondary until, of course, it doesn’t. Soon Hachi and Kishi’s widow sneak away to his reclaimed hut for passionate, lustful sex that eclipses all other concerns.

A persistent theme in Shindo’s films starting in the 1960s is his concentration on sexuality’s place in our everyday lives; specifically, the spectrum of female sexuality, ranging from love to the use of sex as a weapon. “Our human existence is rooted in sex,” Shindo said. “Though conservatives reject the very idea as dangerous, I would say the way to save us from our own perversity is by confronting sex courageously.” Onibaba was the first of his sexually confronting films, leading to a string of works set during Japan’s feudal period that involve women defined by their sexual objectification as the subjects of desire, obsession, rape, and ultimately death. His first feature after Onibaba was Akuto from 1965, about a courtier who wants a woman so badly that he arranges for the death of her loved ones so that he can have her all for himself. In the chilling conclusion, a servant presents the eerily smiling, decapitated head of the obscure object of desire to the courtier. Another film set in the feudal period, Kuroneko from 1968, closely mirrors Onibaba, following an older woman and a daughter-in-law who are raped and murdered by roving samurai. In the aftermath, the women come back as ghosts, ushered by a black cat spirit—they have sold their souls in exchange for the opportunity to seduce, murder, and drink samurai blood for the rest of eternity. Scholar Keiko I. McDonald noted that Shindo’s female characters are often “paragons of sexuality gone awry, especially female sexuality.” But McDonald also remarked that Shindo viewed sexuality as inseparable from survival; it is an essential part of being human. This theme continues throughout his career, evidenced as recently as Shindo’s The Owl from 2003, about a mother-daughter pair of prostitutes who resort to murder to survive. As for Onibaba, its trio of characters have suppressed their sexuality to ensure their basic survival for so long that all else seems secondary until, of course, it doesn’t. Soon Hachi and Kishi’s widow sneak away to his reclaimed hut for passionate, lustful sex that eclipses all other concerns.

Shindo introduces a supernatural element into Onibaba when, one night, the old woman encounters a masked samurai general lost in the reeds. Dressed in expensive armor, the samurai claims he wears the hannya mask, traditionally used in Noh theater, to avoid spoiling his beautiful face during battle. The old woman claims to have never seen real beauty, a remark that makes the viewer ache with empathy. But then, she also feels no need to preserve that beauty, if it exists at all. Agreeing to guide the masked warrior to the road, she leads him toward the pit, which he cannot see in the dark. She leaps over it, and he falls to his death down the hole, landing atop a pile of discarded human skeletons. She lowers down to remove the general’s armor and mask, but she finds the mask will not come off unless she pulls with a great strain—and with her effort comes much of the flesh from the samurai’s face. Later, she tells her daughter-in-law that she will sell the samurai’s armor to Ushi over time, suggesting that the merchant will pay less for a single large transaction and more for several small transactions. Instead, she uses the samurai’s frightening mask and robes to scare her younger cohort and prevent her from attending her nightly rendezvous with Hachi. And so, each night, the old woman claims she’s heading out to the buyer’s cave to sell samurai armor. Rather, dressing as an onibaba—a Japanese word meaning “demon hag” or “demon woman,” typically represented as a jealous female creature of myth—the old woman intercepts her daughter-in-law. The camera quickly zooms on the old woman’s costume, from the samurai’s drape-like kimono to the mask with its gaping mouth, flared nostrils, and tense eyes. Terrified, the younger woman comes to believe in a peasant version of Buddhist theology, suggesting that sex out of marriage is a sin, and the demon will punish her if she continues to meet Hachi.

Even today, to watch Onibaba is to negotiate a bizarre combination of visual and performative styles. Shindo made several films that experiment with highly stylized period pieces, known as jidaigeki. Rather than the stories of heroic samurai and nobility usually associated with jidaigeki, which reinforced the traditional themes of Japanese storytelling, New Wave filmmakers refigured the same settings and character types with a touch of iconoclasm. Japanese cinematic style itself was a matter of tradition, drawing from venerable representational styles found in theater and painting. Jidaigeki owes its origins to kabuki theater, but Onibaba is far from traditional. As evidenced by the hannya mask, Shindo uses touches of Noh theater in his production. Elsewhere, Otowa, Shindo’s wife at the time, bears the look of a hannya mask, complete with angular eyebrows, wild hair streaked with gray, and a winged liner on her eyes. She looks less like a realistic peasant than an actor in an open-air Noh stage drama. Similarly, Shindo’s choice of the hannya mask allows the viewer to read its various uses in the film without ever changing the mask itself. Such masks have been designed to evoke a range of emotional responses depending on the context of a scene, and the actor behind the mask expresses emotion by maneuvering their posture and shifting the audience’s perspective on the mask. At first, when it appears on the samurai in the reeds, or when the old woman scares away her daughter-in-law from another sexual encounter with Hachi, the mask looks frightening and monstrous. Later, when it has sealed itself to her face, the same mask shifts from a fearsome expression to a look of pain and fear, making it an incredible tool that informs the character behind it.

Shindo found inspiration for Onibaba in a Buddhist fable sometimes called “A Mask with Flesh Scared a Wife,” though it has been written under many other names. The story follows Kiyo, a widow who lost her husband and two children to the warring cruelty of medieval Japan. Living with her mother-in-law, Omoto, Kiyo found solace in the Buddhist lessons of Rennyo, a famous monk of the fifteenth century. Each night, Kiyo would travel to the Yoshizaki Temple to visit Rennyo and learn from his teachings, and each night Omoto would feel jealous that she was left alone. To prevent Kiyo from abandoning her each night, Omoto resolved to dress in an ancestral demon mask and frighten Kiyo on the path to the temple. But when she was confronted by the sight of Omoto’s demon, Kiyo was not frightened nor dissuaded from her journey to the temple. Disappointed, Omoto returned home and attempted to remove the mask, but it would not come off. She suffered like that until Kiyo returned home, at which point Omoto confessed to Kiyo that she had dressed as a demon to frighten her. Omoto apologized and asked forgiveness, and Kiyo suggested that she should pray. When Omoto prayed, the mask came off in a demonstration of the Buddha’s mercy. From then on, both the mother-in-law and her daughter visited the temple and found value in Rennyo’s lessons.

Shindo found inspiration for Onibaba in a Buddhist fable sometimes called “A Mask with Flesh Scared a Wife,” though it has been written under many other names. The story follows Kiyo, a widow who lost her husband and two children to the warring cruelty of medieval Japan. Living with her mother-in-law, Omoto, Kiyo found solace in the Buddhist lessons of Rennyo, a famous monk of the fifteenth century. Each night, Kiyo would travel to the Yoshizaki Temple to visit Rennyo and learn from his teachings, and each night Omoto would feel jealous that she was left alone. To prevent Kiyo from abandoning her each night, Omoto resolved to dress in an ancestral demon mask and frighten Kiyo on the path to the temple. But when she was confronted by the sight of Omoto’s demon, Kiyo was not frightened nor dissuaded from her journey to the temple. Disappointed, Omoto returned home and attempted to remove the mask, but it would not come off. She suffered like that until Kiyo returned home, at which point Omoto confessed to Kiyo that she had dressed as a demon to frighten her. Omoto apologized and asked forgiveness, and Kiyo suggested that she should pray. When Omoto prayed, the mask came off in a demonstration of the Buddha’s mercy. From then on, both the mother-in-law and her daughter visited the temple and found value in Rennyo’s lessons.

In Onibaba, Shindo’s conclusion is quite different. The roles of the older and younger woman change in the finale. When the daughter-in-law returns to their hut after being with Hachi, the finds the old woman cowering in the corner. The rain has sealed the mask to her face, and now she pleads with her daughter-in-law to help remove it, apologizing for her trickery and cruelty. The desperation of this moment is heightened by dramatic irony, as the young woman remains unaware that, after her last encounter with Hachi, he was killed by a wandering samurai. Nevertheless, the daughter-in-law agrees to help the old woman remove the mask, but only if she will no longer interfere. The old woman humbly agrees, and the daughter-in-law attempts to remove the mask. It will not budge. She takes a mallet and pounds on it, causing the old woman to issue screams of agony. Blood trickles from behind the mask until it finally cracks, giving way to the old woman’s grotesque face, now covered in oozing wounds. Frightened by the sight of corrupted flesh, her daughter-in-law flees the hut into the reeds, convinced her mother-in-law is a demon. The old woman gives chase, desperate and pleading, “I’m not a demon—I’m a human!” Racing on a familiar path, the young woman leaps over the pit. Behind her, the mother-in-law rushes toward the pit in an identical series of shots, and she makes the same leap. Shindo freezes the frame in mid-air, leaving her fate suspended. Is she doomed to the same death that she purveyed on so many samurai? Or will she clear the distance, heal her face, and find some other way to survive?

The horror of Onibaba’s final sequence is accelerated by Shindo’s mixture of aural and visual stylization, an element present in the film since the title sequence. Hikaru Hayashi’s unconventional music ushers the film into a postmodern style with a wild jazz undercurrent to the thumping drums that carry through the remainder of the film. Shindo also creates a haunting soundscape with the swaying reeds, using the rhythm of the wind to create a persistent aural pattern, a stark contrast in the film when there’s an absence of a non-diegetic score. Shindo also cuts to the reeds in a ghostly slow-motion, settling on their movement in the wind. It’s a technique he also employs using bamboo trees in Kuroneko, whose mother and daughter-in-law are also wrapped up in lust, murder, spirits, and a young man named Hachi. Moreover, Shindo employs various theater types to inform the visual style. Though the film’s setting of an outdoor stage and use of the hannya mask may derive from Noh theater, the influence of kabuki theater is evident inside the women’s hut, where a theatrical expressiveness is apparent in Shindo’s use of lighting. Note how overhead lights fade out and re-illuminate as the characters move throughout the hut, as though this medieval space somehow came equipped with stage lighting. Although twentieth-century Japanese filmmaking relied on theatrical influences to determine their cinematic style, it was not until the New Wave in the 1960s that directors such as Shindo began to experiment with such unique and playful combinations.

Unconventional style aside, the message and significance of Onibaba have been debated. Richie downplayed its implications for postwar Japan, suggesting it was “so filled with naked flesh and sex” that audiences hardly noticed the film’s allegory. Other writers have argued that the film’s message would have been unmistakable to contemporary audiences. Considering that Shindo spent much of the 1950s making films about hibakusha, people affected by the atomic explosion in Hiroshima in 1945, it seems likely that his concerns would carry into Onibaba, even if his remarks have been captured in the subtext. But the film’s message is not subtle; it takes place on a landscape shaken by catastrophe in the highest sectors of the establishment, leaving its peasant characters in a desperate survival mode. Shindo seems to discuss the difficulty of survival for the lower social classes, and thus he censures the government—represented in the film by the masked samurai general—that makes survival so unbearably difficult for peasants. In a way, Onibaba addresses how the choices made by those in power, from politicians to the upper classes, have outcomes that reverberate downward on the social ladder. The ultimate effect of these choices is seen on the old woman’s horrifically scarred face, the make-up for which was based on the radiation burns of hibakusha. In a film constructed in theatrical styles and expressiveness, the grotesque realism of the old woman’s wounds is a stark contrast and would have been all too familiar for Japanese viewers in 1964.

Unconventional style aside, the message and significance of Onibaba have been debated. Richie downplayed its implications for postwar Japan, suggesting it was “so filled with naked flesh and sex” that audiences hardly noticed the film’s allegory. Other writers have argued that the film’s message would have been unmistakable to contemporary audiences. Considering that Shindo spent much of the 1950s making films about hibakusha, people affected by the atomic explosion in Hiroshima in 1945, it seems likely that his concerns would carry into Onibaba, even if his remarks have been captured in the subtext. But the film’s message is not subtle; it takes place on a landscape shaken by catastrophe in the highest sectors of the establishment, leaving its peasant characters in a desperate survival mode. Shindo seems to discuss the difficulty of survival for the lower social classes, and thus he censures the government—represented in the film by the masked samurai general—that makes survival so unbearably difficult for peasants. In a way, Onibaba addresses how the choices made by those in power, from politicians to the upper classes, have outcomes that reverberate downward on the social ladder. The ultimate effect of these choices is seen on the old woman’s horrifically scarred face, the make-up for which was based on the radiation burns of hibakusha. In a film constructed in theatrical styles and expressiveness, the grotesque realism of the old woman’s wounds is a stark contrast and would have been all too familiar for Japanese viewers in 1964.

Onibaba’s lingering question hinges on the old woman’s identity as either a human being or a demon. Have her sins transformed her into a demon, or has the feudal setting merely brought her to the brink of humanity? Rather than suggest her transformation into a monster, Shindo sympathizes with her by acknowledging her state in-between personhood and a desperate grotesque. Her murderous choices and decision to repress her daughter-in-law have resulted from a situation passed down by the prevailing authority, the societal structure of feudal Japan that cruelly oppresses its lower classes, forcing them into treacherous and sexually limited lives in order to survive. In that sense, she exacts revenge on her oppressors, issuing some measure of comeuppance with every samurai she drops into the pit. “You made others die,” she tells her victim. “Now it’s your turn.” However, because she sees no other options available, the old woman both jealously lashes out at the desirous impulses of youth and attempts to maintain her survival by ensuring her daughter-in-law remains her partner in crime. She is a victim of the war-torn landscape, but she has also made a sinister choice. This open-ended investigation of national identity relates equally to feudal Japan and the post-nuclear age, where people have been suspended in extreme states of being, somewhere between survival and wickedness.

Given its historical setting, visually dynamic presentation, and open-ended conclusion, Onibaba lends itself to interpretation and symbolic readings. No viewer could be blamed for deciphering the film exclusively as a sexually charged supernatural horror film; others may construe Shindo’s postwar commentary. The film’s openness to analytical readings from a myriad of textual perspectives has assured its place among the greatest Japanese films. Making sense of Onibaba places the viewer in the same position as its characters, situated in a time when “the earth was turned upside-down,” be it from feudal desperation to nuclear aftermath. Frozen in the final shot between extreme states of young and old, prey and predator, human and demon, the mother-in-law epitomizes an ongoing conflict raised by the social structures of both feudal and postwar Japan. Her endurance is central to Shindo’s message, which implies that people must survive, but survival alone obstructs the aspects of life that define what it means to be human: morality, dignity, sexuality, compassion, and personal truth. Somewhere between repentance and the future’s uncertainty lies a resolution to Onibaba’s enduring questions.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Dave!)

Bibliography:

Desser, David. Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema. Indiana University Press, 1988.

Lowenstein, Adam. Shocking Representation: Historical Trauma, National Cinema, and the Modern Horror Film. Columbia University Press, 2005.

McDonald, Keiko I. Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Video. Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review