The Definitives

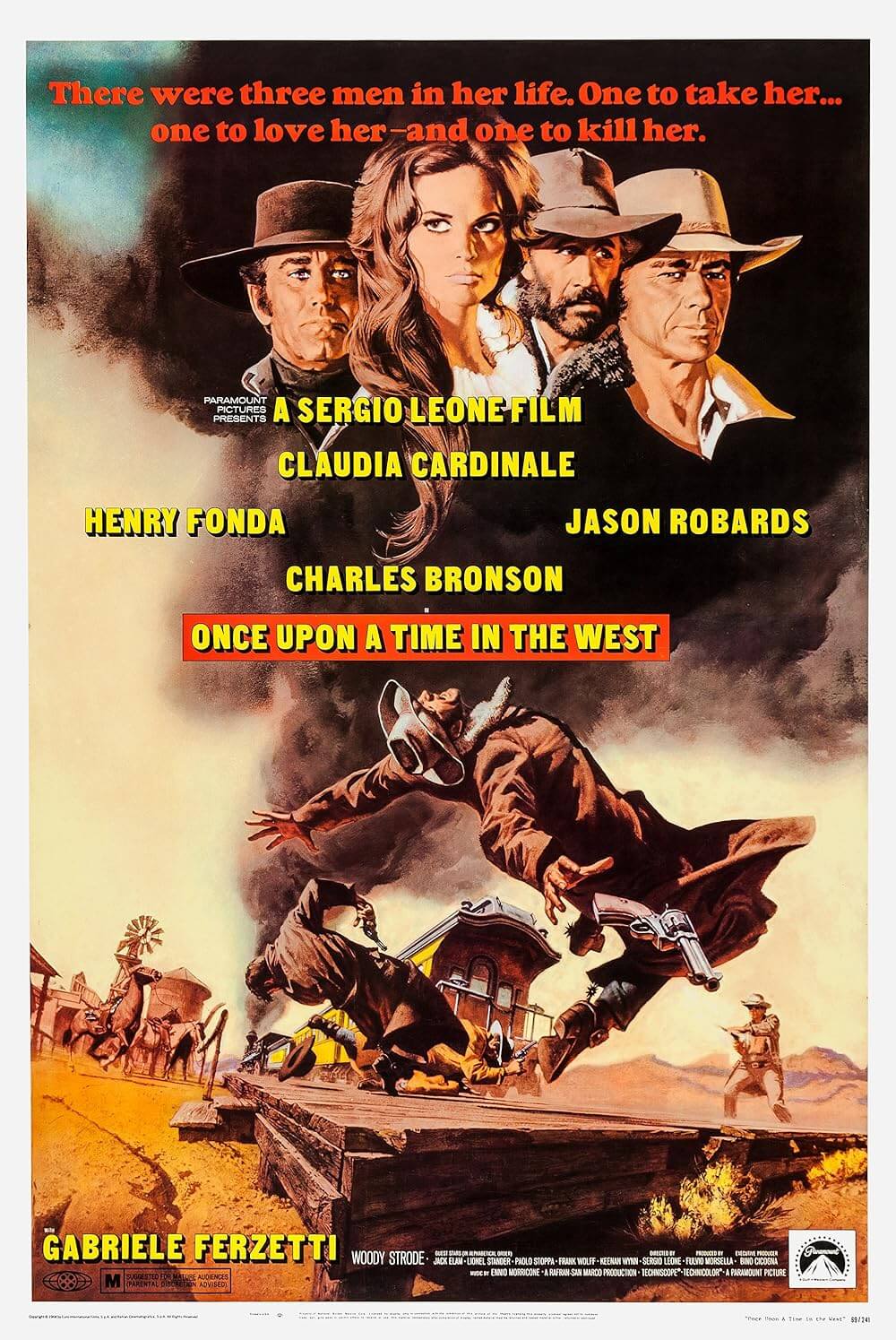

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Sergio Leone’s Westerns radiate pure style. All other elements, including narrative, remain residuary by-products of that style. Informed by the Italian director’s obsession with aesthetics, his extravagant Westerns defy the genre’s conventions through their gritty descriptions and unromantic backdrops, his desire to form a critical alternative to the idealized Westerns that came before. Leone’s most distinctively revisionist material, his Man with No Name Trilogy, contains stories and mannerisms that rebel against standard Hollywood models instituted by filmmakers like John Ford. And yet, however uncharacteristic for his own work, Leone implements the scenario and themes of a typical Western with his 1968 film Once Upon a Time in the West. In presenting a standard story against his radical style, Leone calls attention to his place behind the camera, underscoring how his approach to filmmaking is determined by technique over substance.

The legacy of Sergio Leone subsists in his connection to Italian or “Spaghetti” Westerns, a movement that had been explored before Leone had arrived with A Fistful of Dollars and lasted long after. This reinterpretation of the Western genre, the only genre born and bred in the United States, was initially received with hesitation by U.S. audiences dedicated to John Ford’s ideal of the American West. Shot in European deserts such as Almería and completed with the help of investors from across Europe, the Italian Western became known for its low-budget, extreme violence, coarse appearance, and fatalistic storytelling. Spanish and Italian actors populated the casts playing American and Mexican roles. The filmmakers—including Michael Carreras, director to what is attributed as the first Spaghetti Western, Tierra brutal (The Savage Guns, 1961)—aspired for distinctive methods and, like Leone, sought to imprint their own stylistic mark onto the already defined mores of the genre. But after seeing a Spaghetti Western by Sergio Leone, one never has to see another. His anti-classical approach, preceded by revisionist Westerns such as John Ford’s The Searchers and Anthony Mann’s Man of the West, reinvented the genre in new, playful terminology and cemented future impressions of his Italian subgenre.

As his director father Vincenzo helped forge the Italian silent film and his mother Edvige Valcarenghi was an actress, Leone was virtually born into the film industry. He left law school in his late teens and apprenticed behind several of Hollywood’s contemporary greats. For over a decade beginning in 1947, he served under Raoul Walsh (Colorado Territory), Fred Zinnemann (High Noon), and William Wyler (The Big Country), whose Westerns would later influence his own work. During the 1950s, he became an assistant director of ‘sword and sandal’ epics shot out of Cinecittà Studios in Rome, where he worked on Hollywood productions of Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur. Over time, Leone gained enough high regard so when Mario Bonnard took ill while shooting The Last Days of Pompeii, the studio entrusted him to step in and finish the production. Another historical epic, The Colossus of Rhodes from 1961, became Leone’s first solo directorial effort, although he would never again return to the ‘sword and scandal’ genre.

As his director father Vincenzo helped forge the Italian silent film and his mother Edvige Valcarenghi was an actress, Leone was virtually born into the film industry. He left law school in his late teens and apprenticed behind several of Hollywood’s contemporary greats. For over a decade beginning in 1947, he served under Raoul Walsh (Colorado Territory), Fred Zinnemann (High Noon), and William Wyler (The Big Country), whose Westerns would later influence his own work. During the 1950s, he became an assistant director of ‘sword and sandal’ epics shot out of Cinecittà Studios in Rome, where he worked on Hollywood productions of Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur. Over time, Leone gained enough high regard so when Mario Bonnard took ill while shooting The Last Days of Pompeii, the studio entrusted him to step in and finish the production. Another historical epic, The Colossus of Rhodes from 1961, became Leone’s first solo directorial effort, although he would never again return to the ‘sword and scandal’ genre.

Born from a childhood fascination with the American West, Leone’s colonization of the Spaghetti Western began with A Fistful of Dollars in 1964, based directly upon Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo released three years earlier. With success and attention on Leone’s first Western, Yojimbo’s producers filed a successful lawsuit that accurately claimed Leone based his film on Kurosawa’s without issuing credit; he was forced to pay a hefty compensation. Though Leone lifts his story structure from Kurosawa, who loosely based Yojimbo on Dashiell Hammett’s novel Red Harvest, the director’s unique visual style is undeniable. With its minimalist production and Ennio Morricone’s animated score, the film, despite its problematic story origins, confirms Leone’s voice is a true original in technique alone. His name and popularity would continue to grow with his next two films, For a Few Dollars More in 1965 and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly the following year, completing what he called his Man with No Name Trilogy. Both titles expanded Leone’s method, maturing the story, scale, and runtime in each case to outline his style.

Leone’s Man with No Name Trilogy contains all the indications of his distinctive approach to Westerns, but it also offers narrative themes against which his atypical masterpiece, Once Upon a Time in the West, can be differentiated. Understanding a Sergio Leone Western is tantamount to understanding those of John Ford, the founding father of the genre in Hollywood, in that Ford’s pictures provide Leone with a cast to reshape. Ford’s idealistic plots romanticized the Western frontier as the defining climax of American identity, but Leone’s Westerns are not typically ‘about’ Manifest Destiny. He explored the frontier in all its cruelty, not from a historically accurate perspective, but from a realistic view of the West that brought the rawer details of the frontier into focus with the finesse of a comic book. His characters were not cowboys looking to settle the West or hard-boiled sheriffs protecting the dusty streets of a boomtown—just bandits and bounty hunters and drifters looking to carve themselves up some petty existence. Designations of good and evil are left ambiguous; he acknowledged that lawmen were often as corrupt as the criminals they pursued, and that the frontier was a wild wasteland of lawlessness. Leone’s ongoing protagonist in the Man with No Name Trilogy, for example, was the nameless gun-for-hire played by Clint Eastwood, a narcissistic character devoid of scruples and seemingly driven by the appeal of money alone.

Leone’s Man with No Name Trilogy contains all the indications of his distinctive approach to Westerns, but it also offers narrative themes against which his atypical masterpiece, Once Upon a Time in the West, can be differentiated. Understanding a Sergio Leone Western is tantamount to understanding those of John Ford, the founding father of the genre in Hollywood, in that Ford’s pictures provide Leone with a cast to reshape. Ford’s idealistic plots romanticized the Western frontier as the defining climax of American identity, but Leone’s Westerns are not typically ‘about’ Manifest Destiny. He explored the frontier in all its cruelty, not from a historically accurate perspective, but from a realistic view of the West that brought the rawer details of the frontier into focus with the finesse of a comic book. His characters were not cowboys looking to settle the West or hard-boiled sheriffs protecting the dusty streets of a boomtown—just bandits and bounty hunters and drifters looking to carve themselves up some petty existence. Designations of good and evil are left ambiguous; he acknowledged that lawmen were often as corrupt as the criminals they pursued, and that the frontier was a wild wasteland of lawlessness. Leone’s ongoing protagonist in the Man with No Name Trilogy, for example, was the nameless gun-for-hire played by Clint Eastwood, a narcissistic character devoid of scruples and seemingly driven by the appeal of money alone.

In the face of Ford’s traditionalism, so jealously maintained by Hollywood filmmakers, Leone’s Westerns are radical, anti-ideological, and critical of the genre’s traditional stereotypes. Leone described his films as “Fairy tales for grown-ups”, whereas early Ford pictures might be considered kid’s stuff in comparison. Leone attempted ‘realism’ in his way by counteracting Ford’s conventional ideologies, depicting the unflinching violence of the American West without reserve. In an effort to dispel the Ford model, Leone intentionally overcompensates with his style, exaggerating with a sense of theatricality that lends his pictures grandness, despite their storylines being based around scoundrels on barren, unforgiving land. Though his films center on the lowest forms of life scraping by in the American West, through his brooding attention to detail, deliberately slow and involving pace, and Morricone’s aggrandizing music, Leone supplies his pictures with an uncommon operatic importance so astonishingly ironic given the ragged nature of his scenarios.

Once Upon a Time in the West stands apart from Leone’s other Westerns by affixing the director’s style onto a Fordian saga of Manifest Destiny, the details of which are derived from an extended homage to a number of classic Westerns. He opens his picture with a showdown taken straight from Zinnemann’s High Noon. Three hoods wait at a train station for a man they were hired to kill, a mysterious drifter played by Charles Bronson, dubbed Harmonica for the way he eerily hums on the instrument looped around his neck. When their target arrives, they engage a three-against-one showdown from which only Harmonica walks away. In a plan to say ‘goodbye’ to his title characters from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Leone wanted his established trio together at the train station in the opening sequence. The Bad (Lee Van Cleef) and The Ugly (Eli Wallach) agreed to reprise their roles in the proposed cameo, but Leone and Eastwood had a heavily publicized falling out that prevented The Good from appearing and the idea from coming to fruition. Nevertheless, Leone hired rugged-faced Western icons Woody Strode, Jack Elam, and Al Mulock fill the roles of the three hired guns. The scene in its originally conceived format would have pronounced the auteuristic end of Leone’s stylistic exploration with the Man with No Name films in self-referential vocabulary, and further established Once Upon a Time in the West as a singular declaration of his cohesive, now fully established style. Regardless of his casting choice falling through, Leone’s message is clear.

Once Upon a Time in the West stands apart from Leone’s other Westerns by affixing the director’s style onto a Fordian saga of Manifest Destiny, the details of which are derived from an extended homage to a number of classic Westerns. He opens his picture with a showdown taken straight from Zinnemann’s High Noon. Three hoods wait at a train station for a man they were hired to kill, a mysterious drifter played by Charles Bronson, dubbed Harmonica for the way he eerily hums on the instrument looped around his neck. When their target arrives, they engage a three-against-one showdown from which only Harmonica walks away. In a plan to say ‘goodbye’ to his title characters from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Leone wanted his established trio together at the train station in the opening sequence. The Bad (Lee Van Cleef) and The Ugly (Eli Wallach) agreed to reprise their roles in the proposed cameo, but Leone and Eastwood had a heavily publicized falling out that prevented The Good from appearing and the idea from coming to fruition. Nevertheless, Leone hired rugged-faced Western icons Woody Strode, Jack Elam, and Al Mulock fill the roles of the three hired guns. The scene in its originally conceived format would have pronounced the auteuristic end of Leone’s stylistic exploration with the Man with No Name films in self-referential vocabulary, and further established Once Upon a Time in the West as a singular declaration of his cohesive, now fully established style. Regardless of his casting choice falling through, Leone’s message is clear.

The showdown is followed by the slaughter of the McBain family at Sweetwater farm. Wealthy landowner Brett McBain, his elder son, daughter, and younger son Timmy are gunned down by ruthless villain-cum-industrialist Frank (Henry Fonda) to free up the valuable McBain property for investment, which in time will support the new railroad pushing toward the Pacific. Unbeknownst to Frank and his employer, tuberculosis-ridden businessman Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), McBain was secretly married to an ex-New Orleans prostitute named Jill (Claudia Cardinale) who inherits the McBain land, and also the potential fortune to be had by its connection to the emergent railroad. Arriving that day, Jill makes her way to Sweetwater. Her coach stops at an outpost for rest and she meets the charismatic, freshly escaped outlaw Cheyenne (Jason Robards) and the silent drifter Harmonica, both of whom boast uncertain intentions. She later arrives at the farm to find the funeral in progress for McBain and his children; she is now a widow. The local law assumes Cheyenne murdered the McBain family, though he takes care to clear his name with Jill, as does Harmonica. Both men are impressed by her resolve. The culprit, they all agree, is Frank.

Motivated by the example of Morton, Frank’s hunger to become a powerful businessman is hindered by his criminal instincts—his unrelenting connection to the lawless West, a place slowly deteriorating as the railroad finally reaches its long-sought frontier. Dressed in black attire as a classicized Western villain should be, Frank’s methods rest in violence and intimidation. These methods have made their mark on Harmonica, whose mysterious past alludes to a deadly encounter with Frank long ago. Throughout the film as Frank encounters Harmonica, he asks the stranger his name; Harmonica replies by listing names of the men Frank has killed. This puzzling response is what keeps Frank from killing Harmonica on the spot, as he desperately wants to know this man’s identity. Meanwhile, Frank forces himself on Jill to scare her away from the land, and during an auction, she sells Sweetwater to the highest bidder: Harmonica, who can afford the price after turning in Cheyenne for a bounty, a riskless move as the authorities never keep Cheyenne captive for long. Having kept the land with Jill, Harmonica and Cheyenne arrange for a station and small town to be built on Sweetwater to greet the railroad, while they dispose of Frank’s men to assure she can live in peace.

Motivated by the example of Morton, Frank’s hunger to become a powerful businessman is hindered by his criminal instincts—his unrelenting connection to the lawless West, a place slowly deteriorating as the railroad finally reaches its long-sought frontier. Dressed in black attire as a classicized Western villain should be, Frank’s methods rest in violence and intimidation. These methods have made their mark on Harmonica, whose mysterious past alludes to a deadly encounter with Frank long ago. Throughout the film as Frank encounters Harmonica, he asks the stranger his name; Harmonica replies by listing names of the men Frank has killed. This puzzling response is what keeps Frank from killing Harmonica on the spot, as he desperately wants to know this man’s identity. Meanwhile, Frank forces himself on Jill to scare her away from the land, and during an auction, she sells Sweetwater to the highest bidder: Harmonica, who can afford the price after turning in Cheyenne for a bounty, a riskless move as the authorities never keep Cheyenne captive for long. Having kept the land with Jill, Harmonica and Cheyenne arrange for a station and small town to be built on Sweetwater to greet the railroad, while they dispose of Frank’s men to assure she can live in peace.

Frank, no longer concerned about his dreams of attaining Morton’s level of power, arrives to settle things with Harmonica, knowing the only way he will discover the drifter’s identity is by bringing him to the point of death. They draw weapons and Frank goes down; he falls to his knees, mere moments from death. Harmonica approaches, tearing the instrument from around his neck and placed it in Frank’s mouth. At that instant, Frank recalls killing a man long ago and wedging a harmonica into the mouth of the man’s young brother, who was forced not only to witness the murder, but take part in it. Harmonica is that boy, and though his lifelong quest to avenge his brother is finally achieved, he cannot retire with Jill, who has grown to love him. He and Cheyenne are members of an “ancient race” of men, Western men destined to die out as the railroad modernizes their untamed habitat. In the last scenes, Cheyenne confesses he was shot while taking down Frank’s gang; he dies, and Harmonica carries his body on horseback into the distance. As he does, the train rolls into Sweetwater, ushering a new era and closing another.

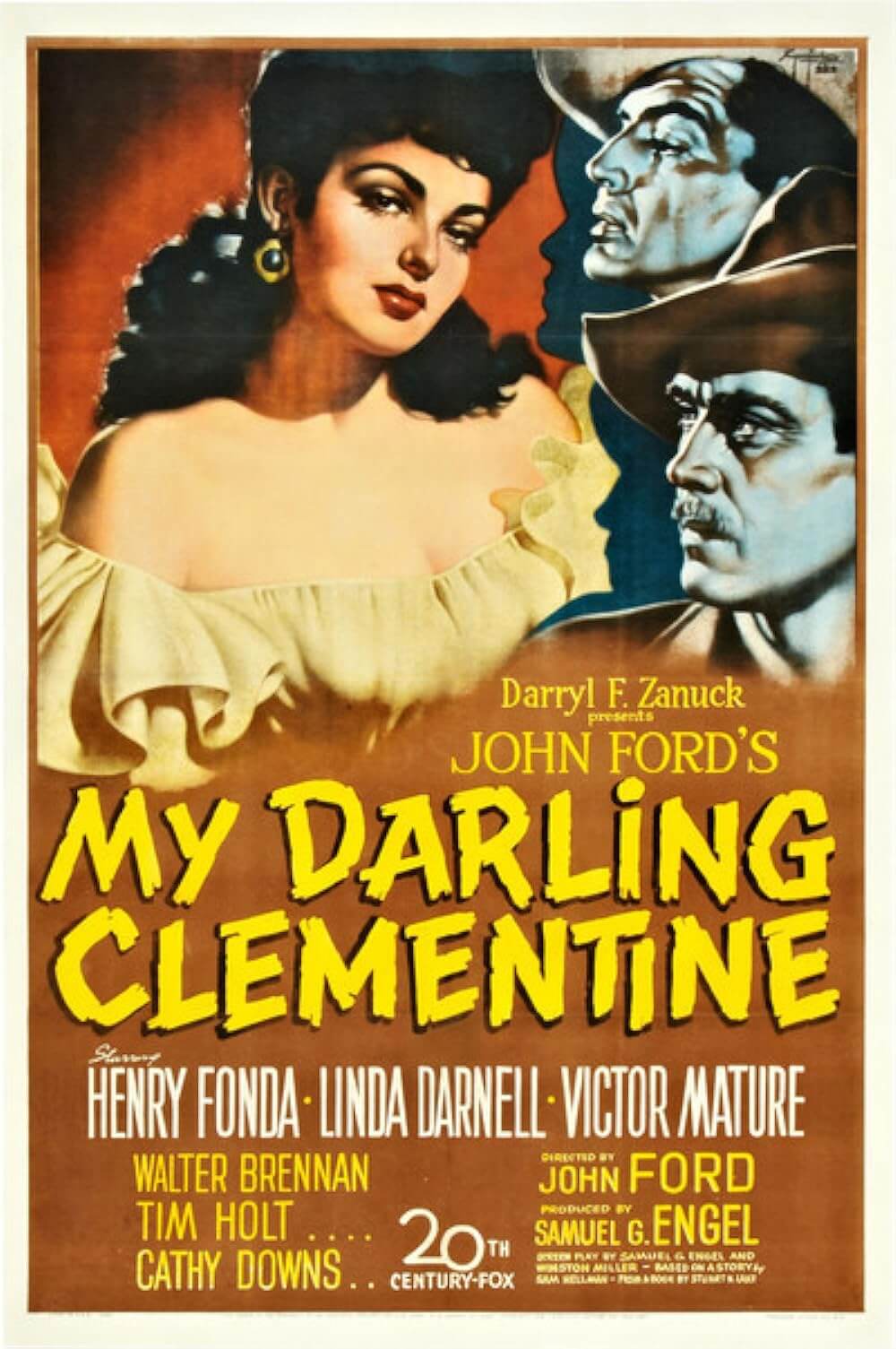

Through his narrative, Leone embraces typified Fordian ideals with his own style to address a less hopeful, more realistic, anti-romantic view of the West—that America found her bearings through the violent journey of often criminal frontiersmen. With the ultimate conquest of the West, pre-Americans such as Cheyenne soon found that their newly civilized frontier no longer had a place for them; but in romantic Ford pictures, like My Darling Clementine or Stagecoach, heroes tame the Wild West and then either advance further westward or settle down to a cultured living. However, Leone supports other classic Western structures, such as opening his film with a reference to High Noon; the McBain farmhouse rests on a desolate plot of land, not unlike the farmhouse in The Searchers; the tough-minded female protagonist Jill recalls Joan Crawford in Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar. Leone’s inclusion of Ford’s signature locale at Monument Valley, which was otherwise conspicuously absent from his earlier films, lends the picture an intended Fordian splendor that the director had previously avoided. But in Leone’s hands, the Monument Valley of John Ford feels like one of the brutal frontier landscapes from Leone’s earlier films, so void of natural redeeming beauty. Ford utilized the rock spires as heavenly gates ushering weary travelers to the Promised Land. Leone uses these familiar geological devices to keep classic Western tropes in his audiences’ unconscious; as a result, in Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone’s style is defined through his embellishments, a presence of “playful excess” on tradition.

Through his narrative, Leone embraces typified Fordian ideals with his own style to address a less hopeful, more realistic, anti-romantic view of the West—that America found her bearings through the violent journey of often criminal frontiersmen. With the ultimate conquest of the West, pre-Americans such as Cheyenne soon found that their newly civilized frontier no longer had a place for them; but in romantic Ford pictures, like My Darling Clementine or Stagecoach, heroes tame the Wild West and then either advance further westward or settle down to a cultured living. However, Leone supports other classic Western structures, such as opening his film with a reference to High Noon; the McBain farmhouse rests on a desolate plot of land, not unlike the farmhouse in The Searchers; the tough-minded female protagonist Jill recalls Joan Crawford in Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar. Leone’s inclusion of Ford’s signature locale at Monument Valley, which was otherwise conspicuously absent from his earlier films, lends the picture an intended Fordian splendor that the director had previously avoided. But in Leone’s hands, the Monument Valley of John Ford feels like one of the brutal frontier landscapes from Leone’s earlier films, so void of natural redeeming beauty. Ford utilized the rock spires as heavenly gates ushering weary travelers to the Promised Land. Leone uses these familiar geological devices to keep classic Western tropes in his audiences’ unconscious; as a result, in Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone’s style is defined through his embellishments, a presence of “playful excess” on tradition.

Place Once Upon a Time in the West alongside the archetypal Ford classic My Darling Clementine and the contrasts emerge. Both films star Henry Fonda, concern taming the wild frontier, and consider the role of one woman character vital to the West becoming a place of progress. Leone had originally sought Fonda to play Clint Eastwood’s role in the Man with No Name Trilogy, but the actor turned down the part. Only after seeing the trilogy, and after much pestering from Leone, did Fonda finally accept the role as Frank. By casting Fonda, Ford’s penultimate leading man after John Wayne, he attacks the audience with their own preconceived notions about Fonda and Westerns. Audiences accustomed to the good-mannered Fonda of My Darling Clementine and Drums Along the Mohawk find themselves confronted by a despicable villain in Frank, whose first appearance ends when he shoots a child while calmly bending a sadistic smile.

The ex-prostitute Jill, the antithesis of Cathy Downs’ hopeful schoolmarm of Clementine Carter who promises to bring education and manners to the West, more resembles Doc Holliday’s saloon girl Chihuahua. Claudia Cardinale plays Leone’s only female protagonist in a genre whose women are usually defined through their vulnerable sexuality. Through rape or the threat of rape, Western women rarely extend beyond a motivational device for a male protagonist. Indeed, even Cardinale’s Jill becomes subject to an unpleasant sexual encounter with Frank, but the incident could scarcely be described as a ‘rape’ with all the violent connotations of the word. Frank simply appears on top of her, and Jill hardly struggles. Frank is almost shocked that Jill helps him undress her, while she merely wants to get it over it with. She gives in because she resolves that enduring the discomfort of Frank’s advance allows her a future, whereas putting up a fight may incite Frank to put a bullet in her head. The incident is “just another filthy memory” for her. Still, the scene plays with undeniable unease, and its message can be easily misinterpreted, especially given the general masculinity behind all Leone films.

The ex-prostitute Jill, the antithesis of Cathy Downs’ hopeful schoolmarm of Clementine Carter who promises to bring education and manners to the West, more resembles Doc Holliday’s saloon girl Chihuahua. Claudia Cardinale plays Leone’s only female protagonist in a genre whose women are usually defined through their vulnerable sexuality. Through rape or the threat of rape, Western women rarely extend beyond a motivational device for a male protagonist. Indeed, even Cardinale’s Jill becomes subject to an unpleasant sexual encounter with Frank, but the incident could scarcely be described as a ‘rape’ with all the violent connotations of the word. Frank simply appears on top of her, and Jill hardly struggles. Frank is almost shocked that Jill helps him undress her, while she merely wants to get it over it with. She gives in because she resolves that enduring the discomfort of Frank’s advance allows her a future, whereas putting up a fight may incite Frank to put a bullet in her head. The incident is “just another filthy memory” for her. Still, the scene plays with undeniable unease, and its message can be easily misinterpreted, especially given the general masculinity behind all Leone films.

Much like the title character from My Darling Clementine, Jill serves as a symbol for the film itself. Pure in a stylistic and thematic sense, yet rugged in its characters and the reality of the setting, Jill is the ironic ex-prostitute who brings purifying water to the West through her newly formed town, which McBain named Sweetwater no less. Symbolically aligned with the purity of water yet stricken by the human faults that conquered the Western landscape, Jill is the West, an elemental spring who represents a saving grace for many of the film’s characters. As the owner of Sweetwater and the precious water on that land, she stands as an emblem of Manifest Destiny, while water itself is a primary theme throughout the film. It provides a Holy Grail of sorts, where the cup itself is replaced by land or wells. Key events occur around or because of water: Shootouts transpire around wells on the McBain farm; characters meet when one enters an outpost for a drink of water; Woody Strode’s hired gun Stony waits for dripping water on his hat to collect, then drinks it down before the opening shootout; Morton dreams of the blue Pacific and obsesses over a painting of violent ocean water, and when he dies, he is near a stream, the phantom sounds of the ocean ringing in his ears.

Along with his elemental theme, Leone’s characters are each icons acting out iconographic Western roles; though Leone does humanize them through his melodrama, the film is more about symbols than characters, and his iconography is built through style. The deliberate and methodical pace, what some would call slow but others would call involving, builds to moments modulated into high drama by the score. Ennio Morricone’s sprawling music reaches full orchestral reverberation at crucial dramatic turns, a glorious theme first heard when Timmy McBain comes upon his slain family, or later during the showdown between Frank and Harmonica. At other times, Morricone quietly defines a character with a single instrument, such as Harmonica’s eerily winding tune or Cheyenne’s playful guitar strum. The lack of sound is also essential; ambient noise such as drips and creaks give way to thrilling, suspenseful silence. Music or not, Leone dwells on the monstrous, gargoyle-like faces of his characters; they fill blank landscapes, empty stages of unimpressive design filled with dust and sagebrush and a conspicuous lack of life. He holds dramatically composed shot far beyond where another director would cut to fully submerge his audience in the moment. Self-aware in every respect, from his dynamic framing to the prolonged showdowns, Leone’s meticulous style may distance some viewers from making an emotional connection to his work, but striking dramatic chords is hardly his principal intention.

Along with his elemental theme, Leone’s characters are each icons acting out iconographic Western roles; though Leone does humanize them through his melodrama, the film is more about symbols than characters, and his iconography is built through style. The deliberate and methodical pace, what some would call slow but others would call involving, builds to moments modulated into high drama by the score. Ennio Morricone’s sprawling music reaches full orchestral reverberation at crucial dramatic turns, a glorious theme first heard when Timmy McBain comes upon his slain family, or later during the showdown between Frank and Harmonica. At other times, Morricone quietly defines a character with a single instrument, such as Harmonica’s eerily winding tune or Cheyenne’s playful guitar strum. The lack of sound is also essential; ambient noise such as drips and creaks give way to thrilling, suspenseful silence. Music or not, Leone dwells on the monstrous, gargoyle-like faces of his characters; they fill blank landscapes, empty stages of unimpressive design filled with dust and sagebrush and a conspicuous lack of life. He holds dramatically composed shot far beyond where another director would cut to fully submerge his audience in the moment. Self-aware in every respect, from his dynamic framing to the prolonged showdowns, Leone’s meticulous style may distance some viewers from making an emotional connection to his work, but striking dramatic chords is hardly his principal intention.

Leone is a director of pure style, as opposed to emotional meaning, and Once Upon a Time in the West has little purpose beyond further defining his mannerist style against the methods of those classicists before him. He celebrates the films of John Ford by merging setting and the theme of Manifest Destiny with his own flourishes, and in turn, creates an incomparable opera-Western whose power resides in the awe he creates around the traditions carved down before him. The result could scarcely be described as a Spaghetti Western, given the film’s devotion to American filmmakers and their conventions, and the notable lack of hopelessness within the story. Rather, this postmodern epic, with all its recycling and references, provides a stage where a grand anastrophe on a classic tale is committed with no end of expressionist wonder.

Bibliography:

Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004.

Frayling, Christopher. Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death. Faber & Faber, London: 2000.

Frayling, Christopher. Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London: 1981.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review