The Definitives

Oldboy

Essay by Brian Eggert |

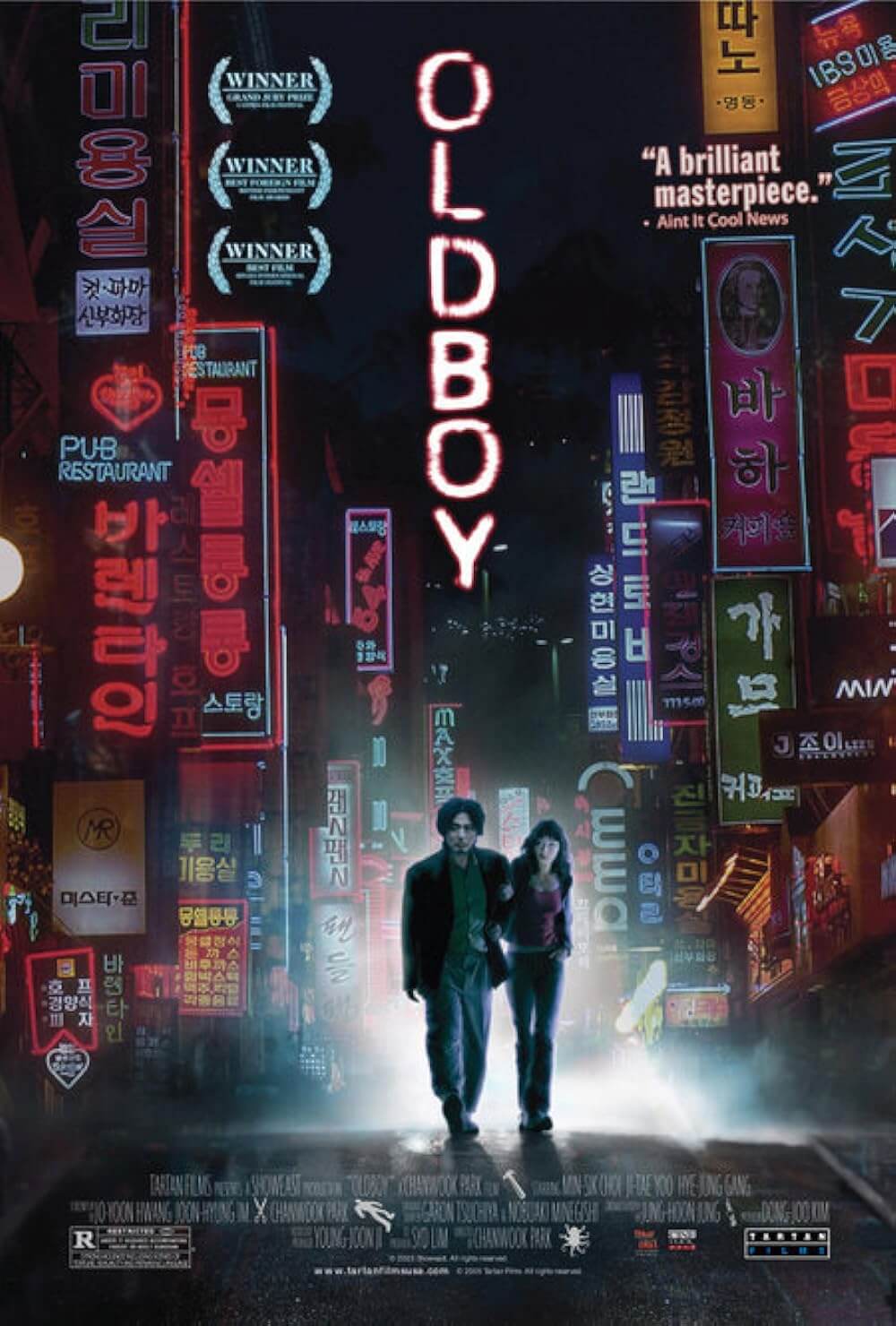

(Note: Celebrating the 20th anniversary of Park Chan-Wook’s cinematic masterpiece, Oldboy will be released in theaters, restored and remastered in stunning 4K, on August 16. This essay is a newly edited and expanded version of one published on March 23, 2009.)

Oh Dae-su has a craving after 15 years in prison. “I want to eat something alive,” he declares. He visits a restaurant, and the chef delivers a live octopus. Oh bites off the creature’s head without hesitation, chomping mouthfuls as he gathers its winding limbs. They cling to him, grasping for life with pointless, automatic effort. This is not a special effect. Four takes and as many octopuses later, and the shot was perfect, the creature’s tentacles suctioning the actor’s face with just the right desperation as he chews. Cook it, slice it up, and serve it with a garnish of pickled ginger, and it’s called sushi. Consume it unprepared, and the act has meaning. Oldboy, by South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook, uses gut-wrenching and visceral imagery to create symbols, assigning ultra-violence, sexual perversity, and torture metaphoric reasoning that ripens the twisting narrative into a stark emotional confrontation. Based on the Japanese manga Old Boy by writer Tsuchiya Garon and illustrator Minegishi Nobuaki, Park’s script uses the source as a springboard. Giving significance to each scene, like The Bard to his stanzas, Park is not a wasteful filmmaker. He explores action, dark humor, and complex motivations, and much of what happens in the film is not fully understood until the last scenes. And by that point, anyone who has watched Oldboy has a feverish desire to watch it again.

That urge to rewatch Oldboy a second time helped turn the 2003 film into a commercial and critical success. It quickly became one of the first major South Korean cinematic exports to connect with an international audience, launching the country’s Film Renaissance. The South Korean film industry has undergone many shifts since the Korean War (1950-1953), including the strict control of film-making licenses imposed on the industry under Park Chung-hee’s presidency to a relaxing of quota restrictions during the country’s economic boom in the 1980s. The most significant shift came with South Korea’s modernization of its film industry to meet the global demands for better production values, spearheaded under the government’s control. But it was the so-called 386 Generation who became agents of change. Named after the speed of an Intel computer chip, the term refers to people who were born in the 1960s, attended college in the 1980s, and started making films in the computer age of the 1990s. Members of the 386 Generation relied on creativity rather than resources, paving new roads for domestic blockbusters, such as Kang Je-gyu’s box-office hit Shiri (1999), and laying the groundwork for the Korean Cinema Renaissance of the 2000s.

Scholar Jinhee Choi observes that Korean cinema had already undergone a New Wave in the 1980s with a group of filmmakers about ten years older than the 386 Generation, while decades earlier, the country experienced a cinematic renaissance in the 1960s. But unlike the earlier movements, filmmakers of Park Chan-wook’s age started making movies outside of politically turbulent contexts—such as the period in the 1980s when protestors of the 1979 military coup called for democracy, or the post-Cold War uncertainty in the early 1990s. Members of Park’s generation emerged without the urgent need for political and democratic contexts to shape their work; instead, Park and those of his generation made names for themselves in a period of globalization, shaped less by nationalistic concerns and more by wanting to participate in a larger conversation with the international film community. Oldboy made waves by winning the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes International Film Festival, where Quentin Tarantino presided over the awarding jury. The film’s success drew interest to Park’s other work, especially since Oldboy was the second in Park’s thematically linked Vengeance Trilogy, after Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and before Lady Vengeance (2005), making Oldboy the artistic nucleus of the three otherwise unconnected films.

Scholar Jinhee Choi observes that Korean cinema had already undergone a New Wave in the 1980s with a group of filmmakers about ten years older than the 386 Generation, while decades earlier, the country experienced a cinematic renaissance in the 1960s. But unlike the earlier movements, filmmakers of Park Chan-wook’s age started making movies outside of politically turbulent contexts—such as the period in the 1980s when protestors of the 1979 military coup called for democracy, or the post-Cold War uncertainty in the early 1990s. Members of Park’s generation emerged without the urgent need for political and democratic contexts to shape their work; instead, Park and those of his generation made names for themselves in a period of globalization, shaped less by nationalistic concerns and more by wanting to participate in a larger conversation with the international film community. Oldboy made waves by winning the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes International Film Festival, where Quentin Tarantino presided over the awarding jury. The film’s success drew interest to Park’s other work, especially since Oldboy was the second in Park’s thematically linked Vengeance Trilogy, after Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and before Lady Vengeance (2005), making Oldboy the artistic nucleus of the three otherwise unconnected films.

Oldboy’s first scene bursts onto the screen with Cho Young-wuk’s propulsive score and the image of Oh, who stops a man from committing suicide by hanging onto his necktie. Oh proceeds to tell the man the story of his 15-year imprisonment. This is the first of three times Oh will share his story in the film, and with each recitation, the story’s meaning changes—from one of outrage to one of tragedy, and finally to abject desperation. Oh’s first account begins in the late 1980s. He has been arrested and behaves like a drunken windbag in a police station, trying to urinate on the floor, pick fights, and take off his clothes. Finally bailed out by a friend, Oh calls home, promising his daughter that he will return soon. But then he disappears. When the film finds him again, Oh has spent two months locked in what appears to be a shabby hotel room—complete with a shower, bed, and television. The space is fortified with a metal door and brick walls. He cannot leave. His captors, whoever they are, supply daily meals of fried dumplings through a slot in the door. Periodically, an electronic jingle announces the release of sleeping gas, and when Oh regains consciousness, his room has been cleaned and his hair groomed. Television passes the time—shown in a montage of Oh trying to escape, crossed with newscasts charting more than a decade of South Korea’s recent history—and becomes his everything: church, clock, calendar, friend, and lover. Alone and unsure why he has been taken, Oh begins to crack. He sees himself swarmed by ants and even attempts suicide to free himself, only to be gassed again and saved.

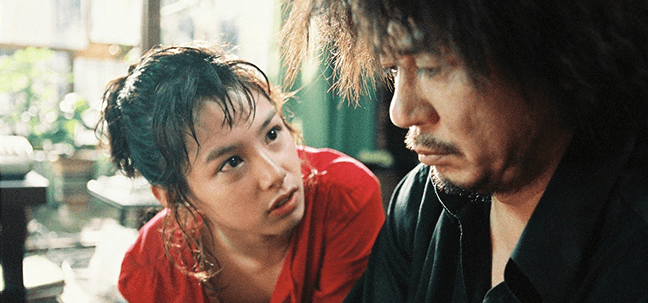

The cycle continues for years without Oh ever knowing who has done this to him or why. The television breaks the news of his wife dying in an accident. He vows revenge, declaring that he will rip apart the body of his tormentor and “chew it all down.” Oh prepares himself by watching kung fu and punching the brick walls to pass the time, developing callus-enforced knuckles with his “imaginary training.” He is plagued by bizarre dreams and hallucinations, and he may be under the spell of hypnosis. Regardless, he journals long lists of potential enemies, and by the stack of notebooks, Oh has not led a distinguished life. “Even though I’m no more than a monster,” he rationalizes, “don’t I, too, have the right to live?” And while he plans an elaborate escape over many patient years, he suddenly finds himself set free by his captors. Emerging from a trunk placed on a patch of grass on a rooftop, Oh is unleashed on the world in a hardened and empty form, his only purpose: revenge. Hungry for life, or perhaps to practice his plan to “chew it all down,” Oh meets sushi chef Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong), whom he saw on television. She serves him the live octopus as a delicacy, but not before he receives a call from his former captor. “Do you know who has done this to you?” the voice asks. Oh guesses a few names from his notebooks, all wrong. The voice discloses, “I’m a sort of scholar. And my major is you.” Just as Oh will seek revenge on whoever imprisoned him, his tormentor has already begun enacting his revenge. Indeed, the “how” of Oh escaping remains less important than the question of “why” someone would want such horrific revenge.

Revenge and horror films with extreme, genre-bending sensibilities became the calling card of South Korean imports to Western audiences in the early 2000s, often sold with the label “Asian Extreme” by Metro Tartan, the primary distributor of what began as cult hits. Only a few Korean directors made films that appealed at home and abroad, at least according to US importers. Bong Joon-ho would make waves with Memories of Murder (2003) and The Host (2007) before defying all expectations with Parasite (2019) and winning six Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Kim Ji-woon also broke into the US market with his supernatural horror yarn A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) and his revisionist Western, The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008). Although such films brightened cinema in Korea under a new commercial light, they played in arthouse cinemas and the festival circuit abroad, along with titles rooted less in excessive violence and gore—the pulp in which Park often traded in during his early career. Filmmakers such as Kim Ki-duk (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, 2003), Lee Chang-dong (Secret Sunshine, 2007), and Hong Sang-soo (Tale of Cinema, 2005), less interested in genre subject matter, also earned a place in arthouses. Only with the advent of Bong’s international blockbusters has South Korean cinema escaped the arthouse in the US, whereas other examples have resulted in uninspired English-language remakes (including Spike Lee’s unfortunate take on Oldboy in 2013).

Revenge and horror films with extreme, genre-bending sensibilities became the calling card of South Korean imports to Western audiences in the early 2000s, often sold with the label “Asian Extreme” by Metro Tartan, the primary distributor of what began as cult hits. Only a few Korean directors made films that appealed at home and abroad, at least according to US importers. Bong Joon-ho would make waves with Memories of Murder (2003) and The Host (2007) before defying all expectations with Parasite (2019) and winning six Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Kim Ji-woon also broke into the US market with his supernatural horror yarn A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) and his revisionist Western, The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008). Although such films brightened cinema in Korea under a new commercial light, they played in arthouse cinemas and the festival circuit abroad, along with titles rooted less in excessive violence and gore—the pulp in which Park often traded in during his early career. Filmmakers such as Kim Ki-duk (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, 2003), Lee Chang-dong (Secret Sunshine, 2007), and Hong Sang-soo (Tale of Cinema, 2005), less interested in genre subject matter, also earned a place in arthouses. Only with the advent of Bong’s international blockbusters has South Korean cinema escaped the arthouse in the US, whereas other examples have resulted in uninspired English-language remakes (including Spike Lee’s unfortunate take on Oldboy in 2013).

On the surface, Oldboy’s status as a breakout film stems from its graphic violence, incestuous themes, morbid laughs, and narrative twists—shock elements that spread word-of-mouth and made the film a must-see success. The initial revenge hook is merely a pretense, delivered in the second act as Oh proceeds to hunt down his former captors. However sensational Oh’s initial reprisals may be, Park has more in mind than a straightforward revenge thriller. What may seem indulgent and grotesque in the first half is later justified as dramatic irony, making additional viewings crucial to process the remarkable intensity of the narrative beyond its initial shock. Shrouded by cryptic allusions and uncertain causalities, Park’s cinematic atmosphere contains a dreamlike quality best described as Kafkaesque. The director even cites Franz Kafka as an influence; though, unlike Kafka, he resists allegory. Oh is persecuted by an unseen oppressor for unknown reasons, just like Kafka’s protagonist in The Trial (1925). Even after Oh is released, he receives taunting, paranoid messages: “How’s life in a bigger prison?” At every turn, Oh and Mi-do, who has joined his quest, realize they are being watched, fuelling the claustrophobic sense that Oh has been released to set upon a path that’s been chosen for him.

Furthermore, Park’s insect imagery draws from Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), another story where isolation leads to change, reflection, and questions about what is real. Is Oh ever truly freed from his prison? How much is Oh acting according to his will, and how much is his tormentor controlling him? After his cephalopod meal, Oh finds himself in Mi-do’s home, waking from a blackout. Both feel like they’ve met each other before. After reading his journals, she remarks on his dreams about ants, wherein they devour him from the inside out. Lonely people see ants, she explains. They signify the dreamer’s desire to become part of a hive or collective. Mi-do dreams about ants too, or rather a human-sized ant creature on the subway, sitting by itself, isolated. If her dream-ant has no one, what chance does she have? And so, Mi-do, seemingly alone in the world, remains by Oh’s side, eventually as an adoring lover who needs him. Meanwhile, Oh tests his theoretical training by confronting five men loitering near a street. He makes short work of them. Then, along with Mi-do, he attempts to locate the underworld prison where he was held by scouting Chinese restaurants with the name Blue Dragon, looking for the same dumplings he had eaten for 15 years.

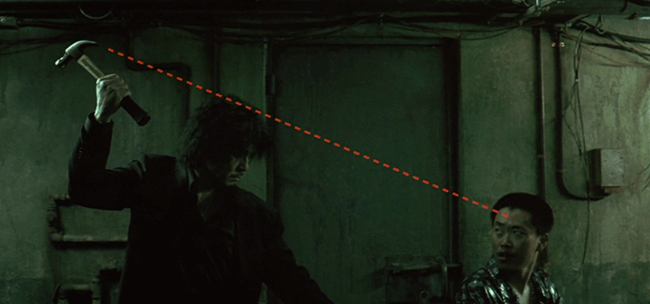

Despite his literary citations, Park never loses his audience to the intellectualism of the literary motifs; rather, he always engages in raw terminology. His objective is to tell a compelling story with depth and a cinematic language whose potency cannot be denied. Oh begins his bloody revenge on the hotel manager, Mr. Park (Oh Dal-su). Once he finds the hotel-prison’s location, Oh proceeds to tape down Mr. Park and, using a hammer, he removes one tooth for every year he was imprisoned. Finished, he enters a hallway filled with the hotel-prison’s goons. The director and his frequent cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon adopt a side-scrolling tableau view of a massive brawl, wherein Oh defeats twenty-some thugs with his strength, his sharpened will, and the hammer. One of Oldboy’s most famous scenes, the hallway fight depicts a somewhat clumsy and desperate form of combat, far removed from the usual look of martial artists in cinema. Shown in a single bravado take that lasts nearly three minutes and charts Oh’s growing exhaustion, the sequence inspired many like it. Martial arts coordinators have since paid homage through elaborate hallway fights in Netflix’s Daredevil and The Raid: Redemption (2011), among others. While the chaotic battle and Oh’s astonishing victory position him in the role of a hero, he will be crushed as the story unfolds.

Despite his literary citations, Park never loses his audience to the intellectualism of the literary motifs; rather, he always engages in raw terminology. His objective is to tell a compelling story with depth and a cinematic language whose potency cannot be denied. Oh begins his bloody revenge on the hotel manager, Mr. Park (Oh Dal-su). Once he finds the hotel-prison’s location, Oh proceeds to tape down Mr. Park and, using a hammer, he removes one tooth for every year he was imprisoned. Finished, he enters a hallway filled with the hotel-prison’s goons. The director and his frequent cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon adopt a side-scrolling tableau view of a massive brawl, wherein Oh defeats twenty-some thugs with his strength, his sharpened will, and the hammer. One of Oldboy’s most famous scenes, the hallway fight depicts a somewhat clumsy and desperate form of combat, far removed from the usual look of martial artists in cinema. Shown in a single bravado take that lasts nearly three minutes and charts Oh’s growing exhaustion, the sequence inspired many like it. Martial arts coordinators have since paid homage through elaborate hallway fights in Netflix’s Daredevil and The Raid: Redemption (2011), among others. While the chaotic battle and Oh’s astonishing victory position him in the role of a hero, he will be crushed as the story unfolds.

Oh’s temporary status as a heroic revenger allows Oldboy to, unfortunately, be misinterpreted as exploitation, even pigeonholed into a category of films that use violence as a primal indulgence of the senses. On the surface, Park’s variety of filmic bloodshed is represented with staggering savagery; he pushes the limits of censorship by suggesting teeth ripped from the mouth with a hammer, scissors stabbing into an ear, and later cutting a tongue from a mouth. Of course, these acts are chosen for their force, their ability to confront the viewer by their concept alone. Park avoids glorifying the act and implies violence by cleverly cutting around the actions themselves—similar to how viewers often remember seeing the savagery in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), though director Tobe Hooper carefully avoided shots of direct impact between tools and flesh. Park shows the tail of Oh’s hammer clasping onto the hotel warden’s incisor like a nail; blood begins to ooze from the victim’s gums, and then Park cuts away to show a collection of removed teeth. If the director were interested in mere exploitation, his camera would have focused on the deed in all its horrible reality. But the gory details are unimportant; thus, they are not shown. The action registers enough significance when communicated through clever if unrevealing edits. Violence takes the blame because the film’s revenge scenes rest on dramatic turns more graphic than the portrayed bloodshed, and the power of those turns makes everything else seem more explicit.

The energy, sensationalism, and even comic idiosyncrasy of Park’s direction, particularly in Oldboy above his other pictures, might distract from the events depicted, except they are just as unexpected. Constructing a thriller that avoids a predictable outcome, where the hero aims to get the bad guy and, in the end, does, Park uses color saturations, intentional grain, and wild formal manipulation to match the volatile and emotionally flayed nature of the story. Had the production any less oomph, the mise-en-scène would be desperate to catch up with the rapidly unraveling narrative. Finding equilibrium between form and function, Park instills purely emotional responses in his viewers. As violent as his picture seems, Park does not intend to exhaust the viewer’s body in their appalled reactions to the film’s extremes. He drains us emotionally, exposing us to a painful dramatic beating that stabs and twists the knife in the final scene. Park’s aesthetic may employ expressive embellishments, but the approach never feels superfluous; rather, his choices are compelled by his characters’ psychology—motivated, slightly deranged, and certainly unreliable given the themes of post-hypnotic suggestion in the film. Elsewhere, Oldboy finds Park experimenting, and some of the production values have not aged well since 2003. Note the blocky CGI used to portray Oh’s forearm, where an ant surfaces and crawls about. The floating countdown clock used in visual transitions also shows signs of Park’s limited resources.

Nevertheless, Park and his fellow 386 Generation of directors often distinguish themselves by aspiring to the refinement of Hollywood and international styles, borrowing and adapting them to South Korean cinema. Compared to earlier Korean films, Park’s generation relied on imported features to learn the trade. In Park’s case, he’s a self-taught filmmaker. Growing up in Seoul under the dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan, Park watched the American Forces Korea Network, which aired Hollywood cinema, often in English and without subtitles. At the time, Korea had few film schools to attend, so he studied philosophy at Sogang University, where he launched a cinema club. He learned the visual grammar of Western filmmaking by watching, resulting not in a Korean style—no national cinema can be reduced to a singular sum of aesthetic traits—but a cinema of globalization and international influence. Park’s self-education continued while he dabbled in short films and struggled to secure backers for upcoming projects, so he paid the bills by writing film criticism. Working throughout the 1990s as an assistant director, screenwriter, and producer, Park’s first breakthrough was Joint Security Area (2000). A thriller and murder mystery set at the DMZ between North and South Korea, his third feature became the country’s highest-grossing film at the time.

Nevertheless, Park and his fellow 386 Generation of directors often distinguish themselves by aspiring to the refinement of Hollywood and international styles, borrowing and adapting them to South Korean cinema. Compared to earlier Korean films, Park’s generation relied on imported features to learn the trade. In Park’s case, he’s a self-taught filmmaker. Growing up in Seoul under the dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan, Park watched the American Forces Korea Network, which aired Hollywood cinema, often in English and without subtitles. At the time, Korea had few film schools to attend, so he studied philosophy at Sogang University, where he launched a cinema club. He learned the visual grammar of Western filmmaking by watching, resulting not in a Korean style—no national cinema can be reduced to a singular sum of aesthetic traits—but a cinema of globalization and international influence. Park’s self-education continued while he dabbled in short films and struggled to secure backers for upcoming projects, so he paid the bills by writing film criticism. Working throughout the 1990s as an assistant director, screenwriter, and producer, Park’s first breakthrough was Joint Security Area (2000). A thriller and murder mystery set at the DMZ between North and South Korea, his third feature became the country’s highest-grossing film at the time.

Not interested in turning Oldboy into a reflector of Korean history or culture, Park presents his film as personal expression and stylistic experimentation, making way for his more sophisticated, restrained, but no less emotionally searing films in the years to follow. Park has regularly told the press that he only decided to become a filmmaker after seeing Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Following the Hitchcockian model, the director finds a unique balance between art and entertainment in Oldboy, embracing each concern equally. He weaves a story wrought with dramatic fire, which, like Vertigo, mutates into something more perverse, drawing from trauma and repressed memories, and yet more strangely evocative as the story advances. Both pictures feature a protagonist whose presence is sympathetic yet disturbed, stripped of layer after layer until laid bare. Whereas Hitchcock’s film relies on emotional torment in his character’s psyche, Park’s film boasts savage physical brutality to signify an appalling psychological affliction, embracing the undeniable connection between mind and body. Both films refuse to allow a straightforward viewing; they deal in fractured minds and obsessive pursuits, and they ask us to reflect on and ultimately participate in an entrenched subjectivity, self-destruction, revenge, and sacrifice.

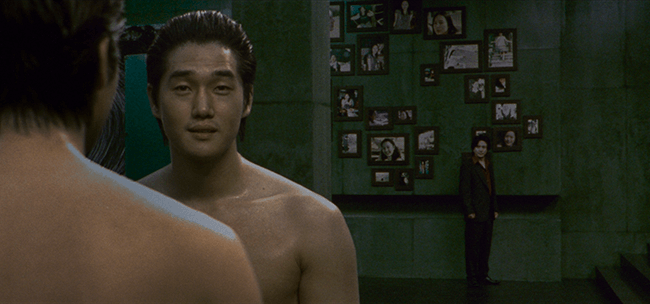

Following a carefully laid trail of breadcrumbs in the form of mysterious boxes and puzzling phone calls, Oh Dae-su discovers his former high school classmate Lee Woo-jin (Yu Ji-tae) is responsible for imprisoning him. Oh’s crime dates back to their teens at Songnok High School, class of 1979, where the alums are called Old Boys. After spying on Lee sexually experimenting with his own sister as teens, Oh told a fellow student what he saw, and the rumor mill became so unbearable that Lee’s sister committed suicide—with Lee clinging to her on the edge of a dam, a shot analogous to Oh saving the suicidal man in the first scene. As much as Oh burns for payback, Lee has smoldered for much longer, plotting his victim’s every move since adolescence and drawing from his considerable financial resources to stage an elaborate revenge. Lee arranged for Oh to meet Mi-do through a post-hypnotic suggestion, and he orchestrated their love affair as incestuous payback. Among the most chilling scenes is when, after Oh and Mi-do make love for the first time, Lee gasses them and joins them on the bed to appreciate his handiwork, caressing Mi-do’s bare hip like the third member of a demented ménage-a-trois. But rather than Oh finally getting his due, he is out-revenged by Lee, who reveals to Oh that Mi-do is actually his now-grown daughter, whom Oh believed to be in another country with a new family.

Lee exacts impossibly cruel justice best compared to Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, wherein scores can only be settled through the vilest retribution imaginable. Pitted between his romantic ardor for his lover Mi-do and paternal love for his daughter, Oh begs Lee not to reveal the secret. On his knees, he vows to do anything to prevent Mi-do from learning this and then volunteers his tongue—which he removes with scissors Lee has conveniently placed on the scene—both as punishment for his gossip-mongering and to protect the truth from Mi-do. No matter how hard Oh tries, Lee has thought of everything, twisting his vengeful blade deeper and deeper, even going so far as to play audio of Oh and Mi-do’s lovemaking so the sounds of passion become nightmarish with the new context. Lee, empty now that his horror show is complete, has no reason to live, and he kills himself. Oh resolves to find the same hypnotist that helped coordinate Lee’s revenge, and he pays her to remove any memory that Mi-do is his daughter—to separate him from the monster he became seeking revenge. Otherwise, there’s no going back; he could never forget what he has done. Under hypnosis, Oh can live happily ever after with Mi-do, free of traumatic memories or the knowledge that they are father and daughter. Ending on a heartbreaking and eerily romantic note, Park’s film asks how far the old saying “ignorance is bliss” extends.

Lee exacts impossibly cruel justice best compared to Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, wherein scores can only be settled through the vilest retribution imaginable. Pitted between his romantic ardor for his lover Mi-do and paternal love for his daughter, Oh begs Lee not to reveal the secret. On his knees, he vows to do anything to prevent Mi-do from learning this and then volunteers his tongue—which he removes with scissors Lee has conveniently placed on the scene—both as punishment for his gossip-mongering and to protect the truth from Mi-do. No matter how hard Oh tries, Lee has thought of everything, twisting his vengeful blade deeper and deeper, even going so far as to play audio of Oh and Mi-do’s lovemaking so the sounds of passion become nightmarish with the new context. Lee, empty now that his horror show is complete, has no reason to live, and he kills himself. Oh resolves to find the same hypnotist that helped coordinate Lee’s revenge, and he pays her to remove any memory that Mi-do is his daughter—to separate him from the monster he became seeking revenge. Otherwise, there’s no going back; he could never forget what he has done. Under hypnosis, Oh can live happily ever after with Mi-do, free of traumatic memories or the knowledge that they are father and daughter. Ending on a heartbreaking and eerily romantic note, Park’s film asks how far the old saying “ignorance is bliss” extends.

When the credits roll, how we should feel about Oh Dae-su’s decision is uncertain. Park’s film continues to leave viewers confused and traumatized into a shocked, emptied numbness, as though Park has cored us until we can supply answers. Does Oh Dae-su’s crooked smile in the last shot suggest that a part of him is not affected by the hypnosis? Is his expression another twisted reflection of the painting on his prison room wall? “Laugh, and the world laughs with you,” the image reads. “Weep, and you weep alone.” If the expression is a smile, then he is blissfully unaware that his love for Mi-do is wrong, which has depraved consequences. If the hypnosis didn’t work, his desire to protect his daughter from the truth has even more disturbing implications if they remain together. In either case, the answer comes with an ugly spin, leaving the viewer uncomfortable and shaken no matter the outcome. But the lasting influence of the film remains its emotional impact. Oldboy broods on the self-destructive vanity of revenge, presenting the most terrible case in the Vengeance Trilogy. Park challenges typical uses of explicit violence by deploying it symbolically in support of his unforgiving, undeniably involving narratives. This visceral storytelling, told with rich visuals, impassioned style, and poetic purpose, makes Oldboy an enduring and unforgettable experience.

Bibliography:

Chee, Alexander. “Park Chan-wook, the Man Who Put Korean Cinema on the Map.” NYTimes.com, 16 October 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/16/t-magazine/park-chan-wook.html. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Choi, Jinhee. The South Korean Film Renaissance. Wesleyan University Press, 2010.

Darcy, Paquet. New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Wallflower Press, 2010.

Gateward, Frances. Seoul Searching. SUNY Press, 2007.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review