The Definitives

Odd Man Out (1947)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

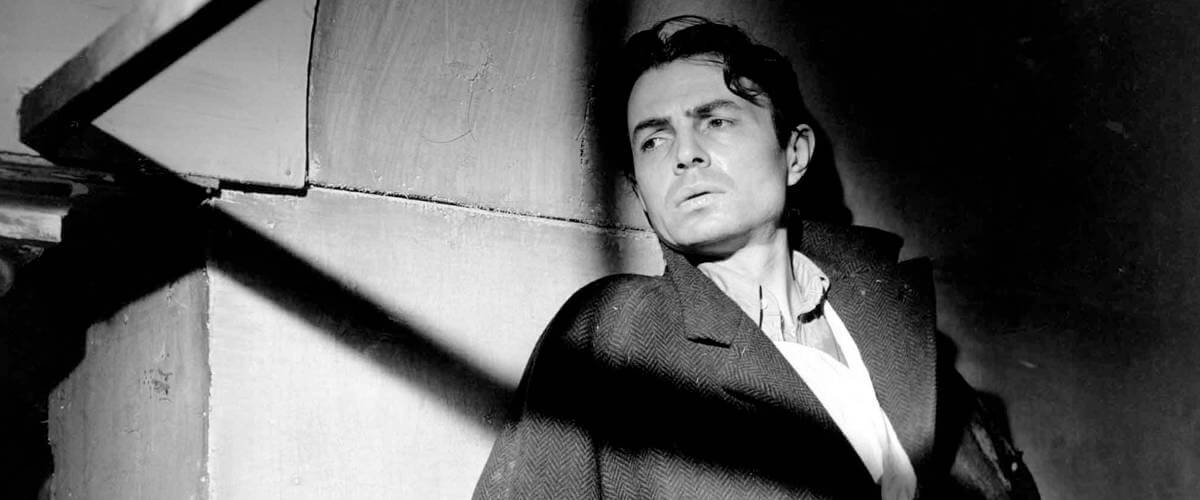

Odd Man Out exists somewhere between realism and expressionism, between an almost documentary level exploration of the perceived real world and an emphatic, stylized one. The 1947 release, one of Carol Reed’s earliest masterpieces, involves an IRA chief, Johnny McQueen, played by James Mason, who takes a bullet during a botched robbery. As he wanders the city injured, stumbling closer to death, he weighs his own conscience against his political ideals. Which one is real, and which one has been built up into something more? The character’s state of mind, his refusal to accept the harsh reality of IRA violence, and the unreal, even delusional notion that one can pursue such a lifestyle without devoted fatalism, haunts the entire picture. As the story continues, he encounters a series of Samaritans, some good, others not, some willing to help, others intent on exploiting a wanted man. Though the story follows an intensely divisive movement, Reed’s characters never adopt a polarized stance; instead, they dwell on their existential tensions. The derelicts, children, nurses, and other wanderers of the night feel much like the protagonist, fragmented yet sympathetic, uncertain and afraid to act. Reed’s deeply powerful approach considers the tragic virtue of passions and the complexity of the individual, representing this inner dichotomy through a virtuoso application of craft. Half in an expressive fever dream, half rooted in a harsh reality, Odd Man Out remains a wholly unique investigation of that which drives the human psyche.

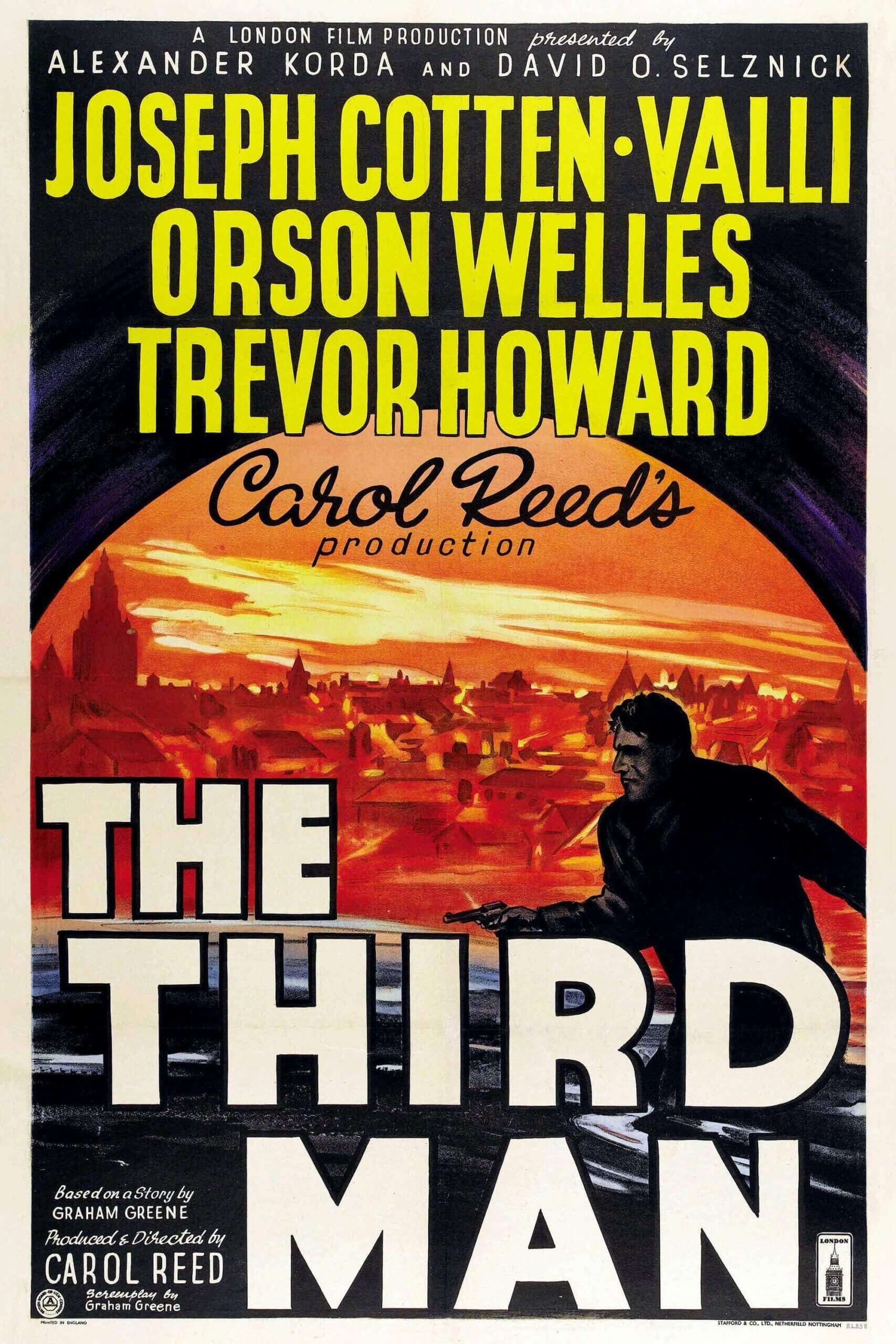

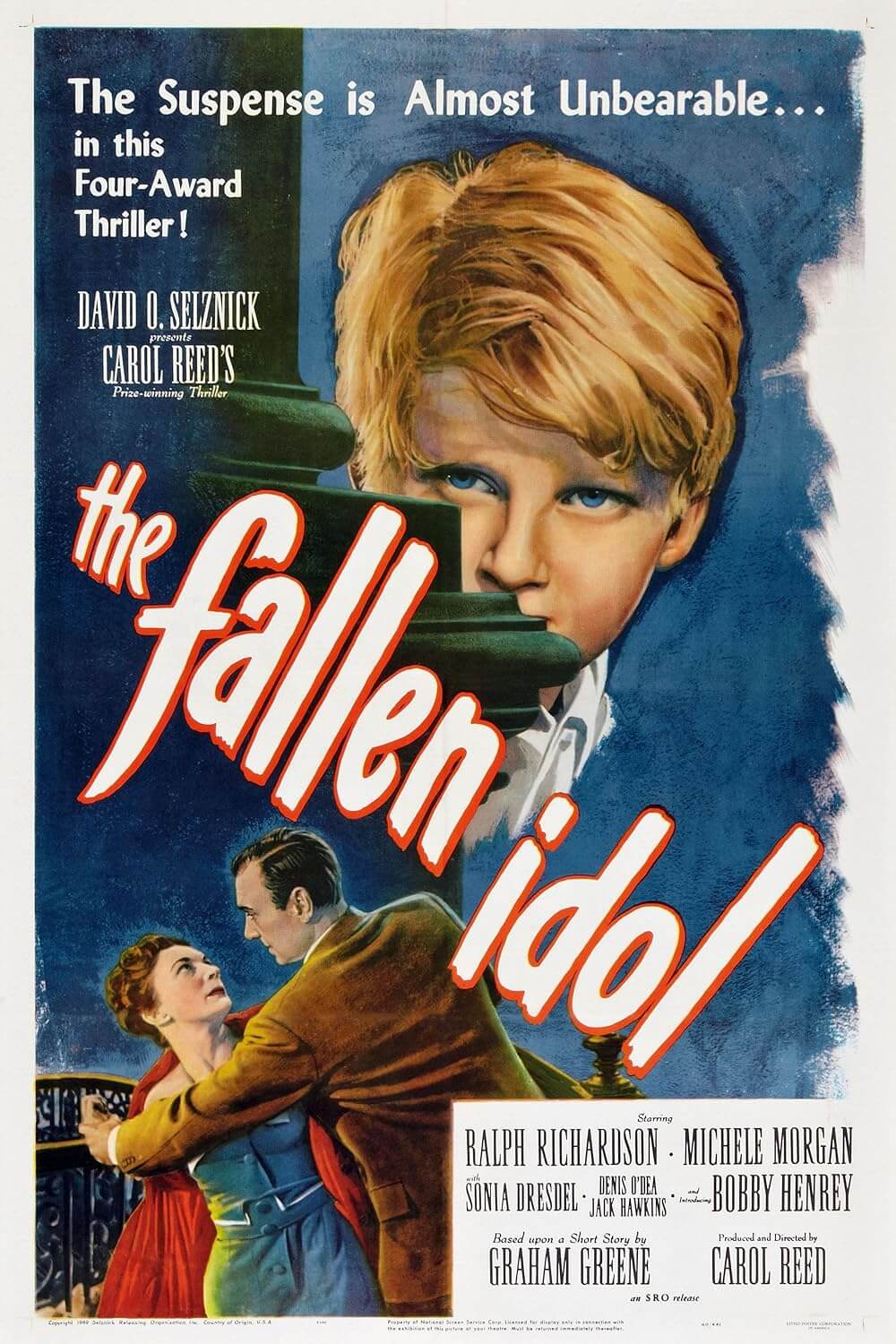

By 1945, Carol Reed had made sixteen films in just nine years, most of them simple genre pieces and studio productions, including Bank Holiday (1938), Night Train to Munich (1940), The Way Ahead (1944), and the propaganda documentary The True Glory (1945). His successes had left him to select his own next project, and he settled on the 1945 book Odd Man Out by author F.L. Green, which he had just read. He resolved to purchase the rights and shoot the film on his own terms, beginning a brief period in his career that produced a string of Reed’s technically virtuoso, thematically rich passion projects. Although Odd Man Out was the first, he followed it with The Fallen Idol (1948), The Third Man (1949), and Our Man in Havana (1959). Rather than deeply personal films, Reed felt a director should “convey faithfully what the author had in mind”, and on these titles Reed had the control he needed to fulfill that objective. With this in mind, he sought out Green to assist in the book’s film adaptation. Green, a Belfast native, had written more than a dozen novels, including On the Night of the Fire, which was filmed in 1939 by Brian Desmond Hurst, and co-starred Diana Wynyard, Reed’s wife. While Green’s book Odd Man Out is an objective, third-person exercise, Reed’s treatment explores the subjective with point-of-view shots that take us inside Johnny’s delirium, but he also explores the lives of those around Johnny. Green co-wrote the screenplay with R.C. Sherriff, and together they all but copied the book’s dialogue into the film, leaving Reed’s expressive style to create the cinematic prose.

Working alongside cinematographer Robert Krasker, who trained in the German expressionist style and later shot The Third Man, Reed developed signatures that would shape the visual language of his next several pictures. In early scenes of Odd Man Out, Reed employs realist visuals, such as the opening shot that hovers over the film’s Irish town like a helicopter, and then slowly transitions through the window of a building, where our characters sit and plan a mill robbery. The robbery, too, appears constructed with an almost neorealist style. In many cases, Reed shoots on streets instead of studio sets and uses non-professional extras, representing much of the working-class without irony or caricature. But after the robbery, when Johnny wanders the city streets half-dead, the film takes on an entirely different, expressive approach. As night falls, the city’s roads shimmer from recent rainfall; Dutch angles convey an off-kilter sense of perspective; high-contrast noir shadows reflect stark situations; bold uses of darkness engulf whole characters. Many of the visual tricks that made The Third Man such a renowned masterwork were employed first in Odd Man Out. For example, in both films Reed places a high light source in the far distance and sends a character running toward it, casting an elongated silhouette of the figure onto the ground, which reaches through the middle and foreground of the composition; the light also creates a sharp contrast, illuminating every brick in the wall and each cobblestone on the road. The director’s opposition of styles gradually builds into a metaphor for Johnny’s mental state.

Working alongside cinematographer Robert Krasker, who trained in the German expressionist style and later shot The Third Man, Reed developed signatures that would shape the visual language of his next several pictures. In early scenes of Odd Man Out, Reed employs realist visuals, such as the opening shot that hovers over the film’s Irish town like a helicopter, and then slowly transitions through the window of a building, where our characters sit and plan a mill robbery. The robbery, too, appears constructed with an almost neorealist style. In many cases, Reed shoots on streets instead of studio sets and uses non-professional extras, representing much of the working-class without irony or caricature. But after the robbery, when Johnny wanders the city streets half-dead, the film takes on an entirely different, expressive approach. As night falls, the city’s roads shimmer from recent rainfall; Dutch angles convey an off-kilter sense of perspective; high-contrast noir shadows reflect stark situations; bold uses of darkness engulf whole characters. Many of the visual tricks that made The Third Man such a renowned masterwork were employed first in Odd Man Out. For example, in both films Reed places a high light source in the far distance and sends a character running toward it, casting an elongated silhouette of the figure onto the ground, which reaches through the middle and foreground of the composition; the light also creates a sharp contrast, illuminating every brick in the wall and each cobblestone on the road. The director’s opposition of styles gradually builds into a metaphor for Johnny’s mental state.

For the purposes of appreciating Reed’s approach and how it relates to the film’s penetrating themes, each scene deserves attention in this assessment of Odd Man Out’s story, both on a visual and dramatic level. The setting is, based on visual cues anyway, Belfast, although the opening titles name it only “Northern Ireland” because, perhaps, the filmmakers want us to see the film’s city as any Irish settlement (then again, Reed may have been trying to keep the location uncomplicated for inexperienced U.S. audiences, or maybe it was unnamed as a symptom of postwar cinema, because wartime films rarely cited actual names of locations to keep their metaphoric meaning intact). Mason’s Johnny McQueen is a fugitive who served eight years of a seventeen-year sentence for importing guns, but has since escaped and spent six months in hiding. Nevertheless, when he’s introduced, Johnny sits in the window, looking out, the curtain open. This moment is strange and symbolic. He is a wanted man, after all; sitting visible in the window seems to signal his desire to be captured, or at least remove himself from the action. Johnny remarks that it’s supposed to snow later. The moment seems to deliver inconsequential information; its significance is not apparent at the time. Only later, when Johnny’s forecast comes true, does the snow falling give us a sense of coming closer to the end. Having been housebound with Grannie (Kitty Kirwan) for so long, Johnny has become weak, and now his men have doubts—especially when, while discussing their robbery, he warns the others to go easy on the guns. His girl, Kathleen (Kathleen Ryan), worries about him. His right-hand Dennis (Robert Beatty) offers to take his place, since Johnny might be recognized; nevertheless, Johnny is determined to join the robbery, perhaps so he doesn’t look weak, perhaps out of foolish pride, or perhaps to test himself.

Johnny’s inner conflict manifests itself in vertigo and hallucinations. As they drive toward the mill, Johnny’s vision goes blurry and he’s overcome by dizziness, images of the city and vehicles spinning in his mind, represented with cockeyed angles, frenzied camerawork, and sped-up film stock to show his disorientation. Once there, Johnny, Murphy (Roy Irving), and Nolan (Dan O’Herlihy) carry out the robbery inside, dressed as businessmen. Outside, Pat (Cyril Cusack) sits in the parked getaway car, nervously watching a coal carriage backing up in the road; he worries that it will block their escape. Just after the score, the alarms sound and the men race to the getaway car. Just then, Johnny loses himself in vertigo once more and stops, disoriented. In this moment, he’s confronted by an armed security guard and during the struggle, the guard shoots Johnny in the shoulder, and Johnny shoots back. The guard is dead. Murphy and Nolan begin to pull Johnny into the car, but Pat takes off, afraid that the carriage will cut off their route. Johnny barely hangs on as Pat races away, until the car takes a sharp turn around a corner and sends Johnny tumbling into the street. Still panicked, Pat continues on before stopping. He argues with the others about whether there’s time to recover Johnny. Just then, Johnny stumbles to his feet and runs down a side road.

Johnny gets away, albeit chased by a dog, and staggers into an air raid shelter, blood trickling down his arm, the mill’s alarm audible in the distance. Once he settles in, we see a montage of a manhunt underway, police asking questions and checking identification papers. A gang of children begins to pester the authority. “Could I have the thousand pound reward if I catch Johnny?” one boy says. Another boy with a wooden gun goes bang-bang at a policeman and declares “I’m Johnny McQueen!” Children have a conspicuous presence in Odd Man Out; they appear in every few scenes and expand the thematic weight of the film into something profound. Reed seems to be saying that adults have made a mess of the world, whereas children belong to no organization; they have no politics and remain idealists. Reed would go on to explore the innocence of children, and the corruption of adults, in films like The Fallen Idol and Oliver! (1968). The juxtaposition of children and IRA soldiers cannot help but draw comparisons between the two idealist types. Consider Pat, who, upon his introduction, sits with a teddy bear on his lap, an image describing Pat as childlike, not serious, not as committed as the others, which is why he panics and speeds away after the robbery. Indeed, after the scene with the children, the film cuts to Pat, lying, or at least exaggerating to Kathleen like a guilty child, about his role in Johnny’s current predicament. After discussing it, the men agree to go out looking for Johnny. “As long as he’s alive,” Dennis says, “he belongs to the organization.”

Back to Johnny in the shelter, awoken by children playing in the street. One of them, a little girl peddling on a single roller skate, chases a ball inside the shelter and freezes when she sees Johnny. The little girl is the most significant of Odd Man Out’s children; many historians have interpreted that she bears a direct correlation to Johnny. How and why that correlation exists remain the lingering questions. The first time she appears to Johnny in the shelter, she evokes a fever dream where he imagines himself in jail. Some analyses of Odd Man Out have even put forth that Johnny fading back into a prison cell suggests that the entire film is a dream, and that Johnny actually sits in a jail cell, lost in a nightmare where he escapes and, ultimately, dies because of the decisions he’s made and lifestyle he’s chosen. The girl appears again when Dennis is out looking for Johnny. Dennis sees some children playing in the street, acting out their version of the mill robbery, except in their version Johnny knowingly kills the cashiers and the security guard. Dennis approaches, and a swarm of urchins prods him for coinage. He asks Johnny’s whereabouts and about police movement, but they know nothing of it. At that moment, Dennis notices the little girl in the distance looking at him in a way that seems to draw his glance; the camera dollies closer in recognition of her single roller skate. Though the girl remains silent and answers Dennis’ questions with nods and shakes of the head, her single roller skate denotes that she too is an “odd one out”. Or perhaps she represents a guardian angel who will help Johnny arrive at his ultimate fate. After all, her information soon leads Dennis to Johnny’s location, setting off a course of events that leads to Johnny’s death.

Johnny rests in the shelter. The scene is quiet until a young couple, unaware of his presence, enters the space with the intention of making love. But the tearful girl has cold feet. “I don’t want to,” she says. “But you said you would,” the man replies. “…Anyway, I’ve got a stye,” she points out. The quaintness of their conversation offers a startling contrast to Johnny’s grave situation. And then the girl sees him sitting in the blackness. He shouts at them to get out. They know who he is, but they won’t say anything. Meanwhile, Pat, Nolan, and Murphy go out looking for Johnny. After a narrow escape from authorities, the coward Pat proposes they go to Theresa’s (Maureen Delaney), owner of a local gambling parlor, to lie low. Nolan agrees, but Murphy says he doesn’t trust Theresa and heads off to his mother’s house—with good reason too. Theresa makes sure her guests are comfortable, then sneaks off to call the authorities, leading to a sting in which Pat and Nolan are shot dead. These two scenes illustrate what follows in Odd Man Out, which is a series of encounters wherein Johnny is either helped, rejected, or used by those who come across him. Some expect a reward for his capture, others want nothing to do with either Johnny or the police, and others still have their own motivations. When Dennis eventually finds Johnny, he serves as a distraction for his chief’s getaway. The distraction works, but it also means Dennis is spotted and dragged away by police officers.

With Johnny barely able to move, he slogs through the city streets. Mason’s performance is contained within his exhausted and existentially beaten expressions. Pain seems like an afterthought to the moral weight pulling him down, even though the guard’s death has not yet been confirmed. The confirmation finally comes when two women from the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) witness what they believe is a hit-and-run and take Johnny in; while inside, they begin to bandage him and talk about him as if he’s not even there, the way some parents do about their children—another allusion linking idealized criminality to children. Soon enough, when they see his gunshot wound, they realize who Johnny is. He overhears them remark that the security guard is dead. This is his first confirmation that he is a murderer. Though Johnny also overhears them say he’s “dying”, this information hardly seems important next to him taking a life. The women patch him up, give him a drink, and put him out into the growing cold and rain. He is alone, all of his compatriots dead or captured, truly an odd man out in the wilds of the streets. He slips into an empty cab unbeknownst to its driver, which carries him through the police cordon. Once the driver becomes aware of Johnny’s presence, he expresses his sympathy but refuses to get involved. He drops Johnny off in a rubbish heap in a builder’s yard, setting him down inside a bathtub. Almost immediately, a thin waifish man named Shell (F. J. McCormick) emerges and takes a few birdlike hops toward Johnny.

With Johnny barely able to move, he slogs through the city streets. Mason’s performance is contained within his exhausted and existentially beaten expressions. Pain seems like an afterthought to the moral weight pulling him down, even though the guard’s death has not yet been confirmed. The confirmation finally comes when two women from the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) witness what they believe is a hit-and-run and take Johnny in; while inside, they begin to bandage him and talk about him as if he’s not even there, the way some parents do about their children—another allusion linking idealized criminality to children. Soon enough, when they see his gunshot wound, they realize who Johnny is. He overhears them remark that the security guard is dead. This is his first confirmation that he is a murderer. Though Johnny also overhears them say he’s “dying”, this information hardly seems important next to him taking a life. The women patch him up, give him a drink, and put him out into the growing cold and rain. He is alone, all of his compatriots dead or captured, truly an odd man out in the wilds of the streets. He slips into an empty cab unbeknownst to its driver, which carries him through the police cordon. Once the driver becomes aware of Johnny’s presence, he expresses his sympathy but refuses to get involved. He drops Johnny off in a rubbish heap in a builder’s yard, setting him down inside a bathtub. Almost immediately, a thin waifish man named Shell (F. J. McCormick) emerges and takes a few birdlike hops toward Johnny.

Over the next few scenes, the idea of fate grows in Odd Man Out. Fate itself plays a major role throughout the film, whether it be Johnny knowing that the organization is not where he belongs and, in going against what he believes, he triggers his own demise, or simply that all the forces around him seem to converge and direct him toward death. Symbolically, the film anticipates events in the finale in a way that could be described as doom, certainly fatalism. The way Johnny predicts the snowfall, or later, how Kathleen convinces a seaman to allow them onto the boat at 11 p.m., build a sense of imminent finality. The gravest of these occurs when a police inspector (Denis O’Dea) arrives at Grannie’s place and questions Kathleen as to Johnny’s location. The relationship between Kathleen and Johnny is curious and could even be called underdeveloped, except that Ryan’s performance, her sad eyes and wounded features, speak to the otherwise undefined bond between them. As such, her only response the Inspector’s probes is “I’m ready,” which at the time may sound like she’s ready to be taken in for questioning, although it’s more likely that she’s ready to die to keep Johnny safe. When the Inspector leaves, Kathleen gets Grannie’s revolver and heads out to look for Johnny. Kathleen later seeks out Father Tom (W.G. Fay), who may know Johnny’s whereabouts. Father Tom knowingly invites her to hear what another man, Shell, there with a sick bird, has to say. They talk to Shell about his budgerigar with a wounded wing, and gradually it becomes apparent that Shell is using his bird as a metaphor for Johnny. Shell wants to be compensated for his information, but Father Tom has no money to offer; he suggests something more valuable: “A precious particle of faith,”—a notion that Shell does not completely understand and seems to think will afford him actual riches, then leaves to gather up Johnny. Meanwhile, Kathleen pleads with Father Tom to hand over Johnny when he arrives—she explains that she would kill Johnny before allowing him to be captured by the authorities. And because she cannot live without him, she would kill herself too. This declaration is almost enough to make us forget that she has an escape plan.

Recurring shots of the clock tower, which looms over Kathleen as she searches the streets for Johnny, remind us not only of her short timeline but the theme of finality throughout the film, and build Odd Man Out into a tragedy that gradually unfolds before our eyes. By this time, Johnny has stumbled out of the tub and walks through the streets. It has begun to snow, just as Johnny predicted it would. William Alwyn’s score drowns out all non-diegetic street sounds, and Johnny’s mind seems too clouded to receive any aural information. His heavy steps in perfect unison with Alwyn’s tempo, Johnny pulls away his bandage so he’s not recognized as he enters a large Victorian pub. He sneaks into a private booth, but not before being seen by Fencie (William Hartnell), the bartender, who gives Johnny some brandy and tells him to leave. Tired and worn, Johnny refuses to go until closing time. Fencie latches the booth door shut and worriedly looks around to confirm no one else spotted Johnny enter. Shell is not far behind. Like a hound dog, he finds Johnny’s bandage in the street, sniffs it, and follows the scent into the pub. Looking around, Shell quickly assesses that Johnny is hiding in the latched booth. Francie notices and desperately shouts across the pub, “Shell! Have a drink, Shell!” In the booth, Johnny knocks over his stout all over the table. Looking down into the bubbles, he sees the faces of the cashier, the security guard, Kathleen, and others, all repeating their taunts, each one representing a failed personal, moral, or professional obligation. Johnny’s unconscious plagues him, inducing psychosomatic reactions and conjuring terrible dreams like his vision before the robbery, during it, and in the air raid shelter. At this latest hallucination, Johnny can only scream. His shriek is so loud the entire pub quiets in response. Shell thinks fast and incites a barroom brawl, which becomes Francie’s excuse to clear the bar and prevent anyone from seeing Johnny.

But Shell doesn’t get Johnny all for his own. In a nearby, rundown building, Shell lives with a failed painter, Lukey (Robert Newton), who has threatened to beat Shell unless he brings Johnny back to the building for him to paint—he wants to capture the “wonderful thoughts in his eyes,” the eyes of a dying man. After the bar clears, Johnny is brought back to Lukey’s studio where Shell, and their fellow squatter Tober (Elwyn Brook Jones), a failed medical student and dejected philosopher (“We’re all dying”), patch Johnny up as Lukey paints his delirious subject. Lukey, the most expressive character in Odd Man Out, sees in Johnny the overarching theme of the film: “The truth about us all… he’s doomed.” Tober insists that Johnny needs a hospital, but Lukey’s painting is not complete. He’s determined to keep Johnny there, even if he dies. With Johnny’s eyes half-open, the camera tilts to show his feverish state. Now from Johnny’s perspective, the camera circles around into another hallucination. Lukey’s paintings gather together like a crowd, or perhaps a jury bent on judgment, and the grotesque faces and fractured style of Reed’s presentation reflect Johnny’s warped point-of-view, not unlike a German expressionist set from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). In this moment, Johnny rises to his feet, the camera angle low, looking up. A strand of saliva trails from his lip. He raises his hand and quotes I Corinthians xiii, “…I am nothing!” Indeed, for several characters throughout the film, Johnny is nothing more than an object who “belongs” to the authorities, the organization, on a painting, or to Shell in exchange for his precious faith. As Tober leaves to call an ambulance, Johnny begins to leave as well and brings down Lukey’s studio setup, including his easel, and Shell follows with the intention of delivering Johnny to Father Tom.

The sequence in Lukey’s studio is representative of how Reed changes the point of view from scene to scene, only occasionally putting the audience in Johnny’s head, and only then in a delirium. The subjective perspective of Johnny shifts to an objective one during several sequences, such as with the ARP women, and the majority of it takes placed from an objective viewpoint. The first such instance of Johnny’s objectivity occurs when the young couple sneaks away into the shelter to make love early on. There, Johnny is an intruder. This allows Reed to experiment with his actors and make Johnny an observer. For individual sequences, he gathered different actors accustomed to varied styles of acting, some from the theater, some from thrillers, some from comedy. Cusack, normally in comic titles, performs rather buffoonish and pointedly un-serious in an otherwise serious film. Lukey, the painter, behaves so over-the-top that many critics of the time reserved their one censure for his performance. This contrast of acting styles operates outside of convention and places Odd Man Out in a realm all its own, where Reed denies a single genre or style and allows his actors to create a diversity that isolates the objectified character in a given scene. Even the casting has a clever, underlying purpose. Mason rarely played the hero, and here Reed uses that to create conflicting feelings toward a sympathetic, yet ultimately wrongdoing protagonist. Reed later became famous for the strange faces he gathered together for The Third Man—the grotesques, the oddities, the street faces. In the same way, he carefully chooses actors that will inform his film by their presence alone.

By this time, eleven o’clock has come. Kathleen pleads with the seaman to extend her deadline until midnight, and he reluctantly agrees. Shell leads Johnny back to Father Tom, hopping in front of him excitedly, helping him to avoid strangers. Then a police patrol passes. Shell pulls Johnny to the ground for cover and, with Johnny now too weak to stand, he proceeds to get Father Tom, and tells the housekeeper to let Father Tom know they have gone to the square. Johnny has since stood up, awakened by the light from a window, out of which two boys look at the snow, perhaps excited that tomorrow will be a snow day. It’s a fascinating moment of innocence in the midst of otherwise momentous foreboding. Kathleen races to locate Johnny and finds him standing in an archway. Rather than run to him, which would seem to be the cinematic convention in such cases, she tells Johnny to come and see her. The moment almost seems as if Kathleen is testing Johnny to determine if he can walk, and therefore escape, or if she should kill him, and herself, right there. Now the clock tower reads five to midnight in the distance. Johnny goes to Kathleen, and they walk along the railings of the shipyard, snow falling on them. Behind Kathleen, we see a line of headlights and flashlights emerging from the snow. This is it. Johnny rests against the railing. “Is it far?” he asks. “It’s a long way, Johnny,” she replies. “But I’m coming with you… We’re going away together.” Her hand reaches into her pocket and she removes the revolver. She fires twice at nothing in particular, inciting a barrage of police fire. Though she has not killed Johnny and herself, she has committed murder and suicide by police.

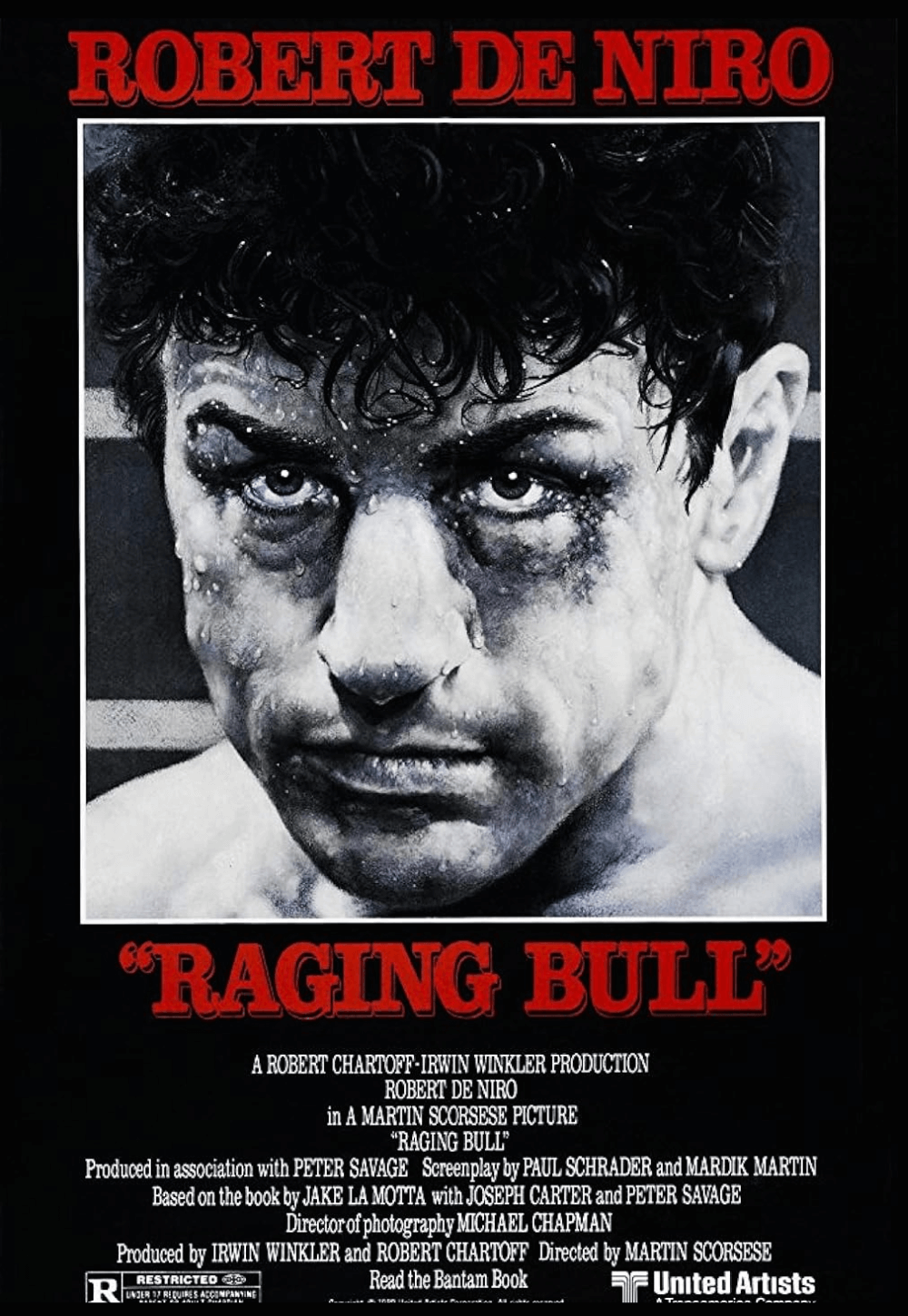

Censors had instructed Reed not to show or imply that Kathleen had killed Johnny herself, but the solution of suicide by police accomplishes the same task—and offers a far more poetic conclusion to the story, as opposed to the typical convention of the authorities capturing their man. Odd Man Out is representative of a trend in postwar cinema where the maligned hero, wrought by existential conflict and consumed by his personal drives, meets his death by gunfire. Such a finale was common among film noirs, and though the film may not involve detectives or small-time criminals, rather an ongoing political movement, the film shares many aesthetic attributes with film noir. Reed’s deep use of shadow and light; a woman who stands by her lover, regardless of his crimes; the criminal protagonist following his own death drive to his ultimate fate—these are all signifiers of film noir. Reed further conforms to film noir stylization by making the film about the individual instead of the movement. For example, the IRA is never mentioned by name; the film’s characters call it “the party” or “the organization”. Nor is there any mention of Catholics and Protestants, or even Republicans and Loyalists. At one point, Dennis infers that Johnny’s heart isn’t in it, and Johnny replies, “This violence isn’t getting anywhere.” Regardless of this exchange, Odd Man Out does not proceed with a political allegory either justifying or condemning the IRA’s actions, nor does it determine that their cause could be resolved through negotiations. Curiously, this is not a political film. Reed’s collaboration with the author resulted in a complete de-politicization of the otherwise biased source material in an effort to produce something more universally appealing. The political themes reside within the subtext, just as the commentary on postwar immorality resides in the subtext of The Third Man‘s involving mystery.

Censors had instructed Reed not to show or imply that Kathleen had killed Johnny herself, but the solution of suicide by police accomplishes the same task—and offers a far more poetic conclusion to the story, as opposed to the typical convention of the authorities capturing their man. Odd Man Out is representative of a trend in postwar cinema where the maligned hero, wrought by existential conflict and consumed by his personal drives, meets his death by gunfire. Such a finale was common among film noirs, and though the film may not involve detectives or small-time criminals, rather an ongoing political movement, the film shares many aesthetic attributes with film noir. Reed’s deep use of shadow and light; a woman who stands by her lover, regardless of his crimes; the criminal protagonist following his own death drive to his ultimate fate—these are all signifiers of film noir. Reed further conforms to film noir stylization by making the film about the individual instead of the movement. For example, the IRA is never mentioned by name; the film’s characters call it “the party” or “the organization”. Nor is there any mention of Catholics and Protestants, or even Republicans and Loyalists. At one point, Dennis infers that Johnny’s heart isn’t in it, and Johnny replies, “This violence isn’t getting anywhere.” Regardless of this exchange, Odd Man Out does not proceed with a political allegory either justifying or condemning the IRA’s actions, nor does it determine that their cause could be resolved through negotiations. Curiously, this is not a political film. Reed’s collaboration with the author resulted in a complete de-politicization of the otherwise biased source material in an effort to produce something more universally appealing. The political themes reside within the subtext, just as the commentary on postwar immorality resides in the subtext of The Third Man‘s involving mystery.

Reviews upon the film’s release were mostly positive. Paul Dehn’s assessment in the Sunday Chronicle called it “more than a milestone” and titled his article “Mason Back – In the Best Film of All Time”. Not all reviews were so unreservedly upbeat, even if Dehn was not the only critic to suggest Odd Man Out was the best British film yet. Of the few who voiced displeasure, writer Edgar Anstey wrote in Documentary News Letter, a publication normally reserved for documentaries, that the film’s message signaled acceptance that the “defeat of all humanity’s aspirations is not only inevitable but aesthetically admirable,” which in turn allows for “malignant forces” such as Hitler’s then-late regime to take power. In other words, Anstey believed the film depicted death at the hands of one’s enemies as a romantic notion, which in turn told audiences to give up on their aspirations. But considering that Reed had intentionally removed any politicization from the material, it’s doubtful his intention was not to put forth real-world parallels. Instead, consider Odd Man Out a film about how we identify ourselves and with others. The Delphic maxim “know thyself” comes to mind, in that the film is not limited to Johnny’s existential journey as an individual, but also includes passages where others objectify the individual. Johnny becomes a victim of both the viewer’s objectification and characters who objectify Johnny. In fact, if someone clocked it, you would find the film spends more time objectifying Johnny than occupying his subjective point of view—and even then, much of Johnny’s perspective is spent in delirium. Still, our needs as viewers demand that we attempt to understand him as he tries to understand himself.

There are moments in Odd Man Out that force us to consider our apathy toward others, our inability to understand or know another individual, or appreciate the value of another human life. Each scene that shows Johnny used or disregarded, standing on the margins of the scene, suggests the plight of the individual and his solitude in the world. The film remains unique as a work of almost didactic art combined with a flourishing poetic realism not seen outside of Marcel Carné’s Le quai des brumes (1938), Le jour se lève (1939), or Les enfants du paradis (1945), where the universe refuses to acknowledge the individual, and therefore the individual is doomed. Though Odd Man Out occupies the stylistic traits of a film noir and the outward elements of a thriller, Reed accomplishes an affecting drama that leaves the viewer reflecting on much. Notice how we never see Lukey’s painting of Johnny, where Lukey has endeavored to capture “that peculiar light in the eyes of a dying man” and, apparently, failed, as he throws down his canvas. Through moments like this one and the fatalistic end of Johnny and Kathleen, Reed delivers a tragic and powerful cautionary tale. The recurring image of the clock tower warns us that our time is limited, far too limited, and in that time, we must endeavor to recognize the individuality of others and ourselves. The consequences of failing to weigh one’s place in the world and align our actions with our ideals are terminal.

Bibliography:

Evans, Peter William. Carol Reed. British Film Makers. Manchester University Press, 2005.

Green, F.L. Odd Man Out. London: Michael Joseph, 1945.

De Felice, James. Filmguide to Odd Man Out. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972.

Mason, James. Before I Forget. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981.

Moss, Robert F. The Films of Carol Reed. London: Macmillan, 1987.

Vaughn, Dai. Odd Man Out. (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, 1995.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review