The Definitives

Ocean’s Eleven (2001)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Is Ocean’s Eleven the coolest film ever made? It’s certainly a contender. But what makes Danny Ocean and his ten professional thieves so cool goes beyond their movie star good looks, stylish wardrobe, chummy camaraderie, and glitzy Las Vegas backdrop. Part of it entails what they don’t do and say. They don’t need violence to rob the world’s most impenetrable safe because they’re smarter than that. They don’t need to articulate every idea because they have an unspoken understanding. And although they’re criminals, they adhere to a personal code that supports the group, which is more than can be said for their target. Director Steven Soderbergh described the film to Entertainment Weekly as “a throwback. Nobody gets killed. There’s no bad language. It’s just an old-fashioned heist movie with lots of stars.” Like many Soderbergh films, Ocean’s Eleven also confronts an unscrupulous commercial entity, represented here by three casinos and their ruthless owner. In an increasingly corporatized world, George Clooney’s Danny Ocean and his crew represent a team of Davids taking on a Goliath who wears expensive suits and thinks of money first. While the house always wins because multinationals have rigged the game against those on the lower end of the economic divide, the viewer watches Danny play a perfect hand. In the parlance of the film’s hero, they bet big, beat the house, and get away with the American Dream of love and money. And they make it look damn cool.

As early as the mid-1980s, Hollywood had been clamoring to remake Ocean’s 11, the 1960 heist movie that marked the first feature starring the Rat Pack (Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop). Sinatra stars as Daniel Ocean, who enlists ten World War II paratrooper buddies to use their military precision to rob five casinos. Cheering from the sidelines, Angie Dickinson and Shirley McClaine round out an impressive cast of protagonists, while Caesar Romero plays the crook who thwarts their plans. Conforming to the Production Code, director Lewis Milestone and the top brass at Warner Bros. delivered a casino heist movie where the thieves go home empty-handed. Trying to outsmart their pursuers, Daniel and his crew hide their money in the coffin of a fellow thief (Richard Conte) who dies of a heart attack, only for the man’s widow to order the coffin to be cremated. Since the Code couldn’t have thieves getting away with their loot—a paltry $5 million—this accident cleared them on moral terms. Unbound by such castigating oversight, the remake’s screenwriter, Ted Griffin, delivered a story that, according to scholar Aaron Baker, changed to reflect the growing wealth inequality in America. If the original was about veterans reasserting themselves in an ever more complex postwar environment, Soderbergh’s remake presented a yarn about the have-nots pulling one over on the ultra-rich.

Since his meteoric debut sex, lies, and videotape earned the Palme d’Or at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, Soderbergh’s career has been eclectic and prolific. Critics and scholars have struggled to define Soderbergh as a singular auteur, while most cannot deny that his body of work is that of a talented and controlled filmmaker. Following his impressive debut, Soderbergh’s career wavered with a string of commercial disappointments: Kafka (1991), King of the Hill (1993), The Underneath (1995), Gray’s Anatomy (1996), and Schizopolis (1996). Then, with so many unfairly dismissed films to his name, Soderbergh took a studio job directing Out of Sight (1998) for Universal. The film jumped on the post-Tarantino bandwagon in Hollywood that led to several adaptations of Elmore Leonard texts into crime pictures in the 1990s and beyond, including Get Shorty (1995), Jackie Brown (1997), Touch (1997), The Big Bounce (2004), and Be Cool (2005). But Out of Sight also marked the first collaboration of six between Soderbergh and George Clooney, which helped ground the actor’s flailing career, making him one of the last true movie stars. Their commercial success together on Ocean’s Eleven and its sequels ensured that their later, less accessible projects would receive funding and creative license. But Ocean’s Eleven is more than a “one for them” project in the longstanding filmmaker equation of “one for them, one for me.” The film contains a sly message under its surface-level glamour and cool-as-a-cucumber scenario.

Curiously, Ocean’s Eleven also marks the third of four remakes in seven years for Soderbergh. It was preceded by the director’s modernization of 1949’s Criss Cross, starring Burt Lancaster, with his 1995 disappointment, The Underneath, headlined by Peter Gallagher. Soderbergh went on to greater acclaim with his film based on Traffik, the BBC miniseries from 1990, which aired on PBS in the United States. The resulting film, renamed Traffic (2000), earned Soderbergh an Oscar for Best Director. He was also nominated for Erin Brockovich that year, and his one-two punch of commercial and critical hits ensured his creative freedom in the ensuing years. Later, in 2002, Soderbergh remade an Andrei Tarkovsky masterpiece with Solaris (2002), a science-fiction box-office flop that remains one of the director’s best. But his remake of 1960’s Ocean’s 11 marked the director’s most unabashed embrace of mainstream moviemaking yet. With its cast of Hollywood A-listers and up-and-comers, and a budget of $85 million—his biggest yet—the production also significantly reconsidered the moralistic original.

Curiously, Ocean’s Eleven also marks the third of four remakes in seven years for Soderbergh. It was preceded by the director’s modernization of 1949’s Criss Cross, starring Burt Lancaster, with his 1995 disappointment, The Underneath, headlined by Peter Gallagher. Soderbergh went on to greater acclaim with his film based on Traffik, the BBC miniseries from 1990, which aired on PBS in the United States. The resulting film, renamed Traffic (2000), earned Soderbergh an Oscar for Best Director. He was also nominated for Erin Brockovich that year, and his one-two punch of commercial and critical hits ensured his creative freedom in the ensuing years. Later, in 2002, Soderbergh remade an Andrei Tarkovsky masterpiece with Solaris (2002), a science-fiction box-office flop that remains one of the director’s best. But his remake of 1960’s Ocean’s 11 marked the director’s most unabashed embrace of mainstream moviemaking yet. With its cast of Hollywood A-listers and up-and-comers, and a budget of $85 million—his biggest yet—the production also significantly reconsidered the moralistic original.

The film unfolds against the backdrop of aggressive corporatization in Las Vegas. Andy Garcia plays Terry Benedict, who operates three luxury hotel-casinos (the Bellagio, the MGM Grand, and The Mirage) with meticulous, possessive attention to every detail. Based on real-life developer Steve Wynn, Benedict is tearing down the old Las Vegas, once known as Sin City, and plans to diversify with broad appeal tourism—upscale restaurants, sporting events, entertainment, and even a curated art museum. Despite his seemingly varied interests, Benedict signifies the rampant corporate identities dominating American business. Note the subplot that involves Benedict buying out the Xanadu from under its previous owner, the old-school Reuben (Elliot Gould). The loss, followed by his hotel’s demolition, motivates Reuben to finance Danny Ocean’s scheme and get revenge on Benedict. After all, Benedict cares about nothing except having control, making money from his investments, and perhaps his golf game. This is clear when his museum curator girlfriend, Tess (Julia Roberts), asks if he likes the Picasso hanging on his museum wall. “I like that you like it,” he deflects, avoiding any discussion that might reveal he has no eye for art. Andrew deWaard and R. Colin Tait describe the film’s conflict as taking on “the indifferent forces of excessive capitalism, with the little guys triumphing in the face of overwhelming odds.”

Against a soulless corporate embodiment like Benedict, who’s armed with an ostensibly infinite bankroll, the titular den of thieves doesn’t seem so bad. Indeed, before meeting Benedict, we meet the newly paroled Daniel Ocean, who just completed a four-year stint in prison. While away, his former wife, Tess, left him for Benedict. Once released, Danny assembles his crew, each with a specific skill needed for their heist of “the least accessible vault ever designed.” He promises them a take of $165 million, divided equally. But while Danny was away, his cohorts have been slumming in menial cons and subpar work, framing the characters as underdogs from various locations around the country: Frank (Bernie Mac) has been dealing cards at a sleazy Atlantic City casino. Brad Pitt’s ever-eating Rusty (who consumes a fruit cup, nachos, shrimp cocktail, etc.) teaches dopey TV celebrities to play poker. The Mormon twins (Casey Affleck, Scott Caan) spend their time in Utah, immersed in petty brotherly competition. The nervous techie Livingston (Eddie Jemison) helps with police wiretaps. Demolition man Basher (Don Cheadle) works with less “proper villains” on a doomed heist. And experienced con man Saul (Carl Reiner) has since retired. Danny also enlists new faces with Yen (Qin Shaobo), a Cirque du Soleil acrobat, and the son of a former colleague, the young pickpocket Linus (Matt Damon).

Structurally, Ocean’s Eleven proves engaging because Soderbergh allows Griffin’s script to carefully disperse details about the heist without revealing its secrets. Part of the joy is that though Griffin was careful enough to write nearly his entire film around the planning of a theft, he leaves the viewer clueless about how it will be done until it’s happening. As a result, the viewer feels like both part of the plan and a spectator of it, creating a sense that we’re on the Eleven’s side, even if we don’t know what will happen next. Here’s what we do know: the robbery will take place in two weeks, requiring the crew to overcome a series of challenges: they must get into the casino cages, overcome fingerprint scanners, avoid motion detectors, go unnoticed by guards with uzis, penetrate an impenetrable vault, and never appear on the omnipresent cameras. The team builds a replica of the vault, snatches an EMP emitter, buys several unmarked vans, and, as Soderbergh’s camera conspicuously underlines, uses a pine-scented air freshener (later revealed to be hanging in their faux S.W.A.T. van). But as to how these items are used, who knows? We will find out later. In the meantime, there are worries about Saul’s health, intertextually emphasized by how Richard Conte’s character dies of a heart attack in the original. Linus’ greenness and ability to perform under pressure cause an injury to Yen’s hand, which could impact his acrobatics in the vault. But most pressing are Danny’s personal motivations for the heist.

Structurally, Ocean’s Eleven proves engaging because Soderbergh allows Griffin’s script to carefully disperse details about the heist without revealing its secrets. Part of the joy is that though Griffin was careful enough to write nearly his entire film around the planning of a theft, he leaves the viewer clueless about how it will be done until it’s happening. As a result, the viewer feels like both part of the plan and a spectator of it, creating a sense that we’re on the Eleven’s side, even if we don’t know what will happen next. Here’s what we do know: the robbery will take place in two weeks, requiring the crew to overcome a series of challenges: they must get into the casino cages, overcome fingerprint scanners, avoid motion detectors, go unnoticed by guards with uzis, penetrate an impenetrable vault, and never appear on the omnipresent cameras. The team builds a replica of the vault, snatches an EMP emitter, buys several unmarked vans, and, as Soderbergh’s camera conspicuously underlines, uses a pine-scented air freshener (later revealed to be hanging in their faux S.W.A.T. van). But as to how these items are used, who knows? We will find out later. In the meantime, there are worries about Saul’s health, intertextually emphasized by how Richard Conte’s character dies of a heart attack in the original. Linus’ greenness and ability to perform under pressure cause an injury to Yen’s hand, which could impact his acrobatics in the vault. But most pressing are Danny’s personal motivations for the heist.

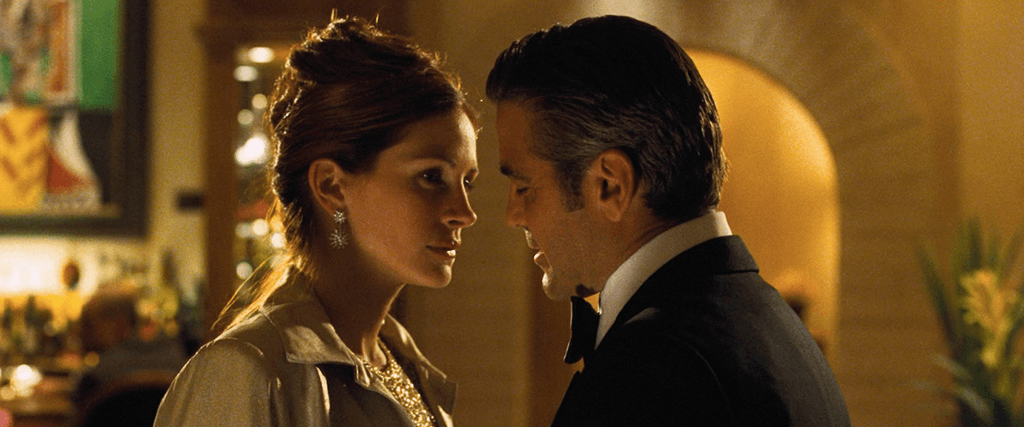

Besides the implication of taking down the super-rich, what’s at stake is a classical conflict: Danny’s masculine identity, which he will restore by reclaiming Tess and asserting his superior intelligence over Benedict with the casino robbery. Rusty isn’t pleased to discover this truth, as he points out: Tess doesn’t split eleven ways. But if all goes according to plan, Benedict will lose his money and Tess. Does Tess even want that, though? Upon seeing Danny again for the first time in four years, she appears angry about her abandonment and declares her commitment to Benedict. The scene finds Danny meeting Tess before her scheduled dinner with Benedict. After Benedict arrives, Soderbergh frames Danny, standing, between Benedict and Tess, sitting. Danny engages Benedict in polite conversation, all the while touching his wedding ring, a detail Tess notices, along with his restrained, affectionate body language and smiles in her direction. This terrifically acted scene establishes the emotional stakes for Danny. Although Tess later tells Danny, “You won’t win me back,” her relationship with Benedict suggests that she’s one of his many possessions, and she knows the relationship is hollow. Only a flashback to Danny saying goodbye to Tess hints that she still has feelings for him: Danny gives her one last hug, and the way she closes her eyes communicates plenty without words. In the end, Danny’s ultimate redemption and victory come not when the viewer realizes that his crew got away with the money, but when Tess races toward him at the end, as police prepare to take him away, and she shouts, “That’s my husband!”

Just as the film keeps the audience guessing what will happen next during the heist, Soderbergh leaves much unsaid for his characters—a crucial aspect of their coolness. This is apparent in the first scene, when a parole board asks Danny, “What do you think you would do if you were released?” The next shot rests on Danny’s face. He thinks about how to respond and doesn’t reply. But whatever he said convinces them, because he’s soon discharged and leaving prison. A similar scene finds Danny and Rusty assembling the crew, with ten down. “You think we need one more?” Danny asks. Rusty, resting his head on the bar, does not respond. “You think we need one more,” Danny affirms. “Alright, we’ll get one more.” Similarly, when Saul tells Danny and Rusty, “Look, we all go way back, and I owe you from the thing with the guy in the place, and I’ll never forget it,” he speaks with a metonymic ambiguity that doesn’t require specifics. Soderbergh’s sense of cool in Ocean’s Eleven stems from his ability to communicate without words or exposition, all while guarding the particulars of the heist and showing that his characters are in control. Even when Danny seems to have lost control, getting himself caught by Benedict’s security right before the heist, it’s part of Danny’s master plan. While some unspoken moments are played for humor, others represent Soderbergh accessing cool by removing clunky exposition and keeping the audience at a distance. Danny’s crew doesn’t always need to speak to each other to communicate, and only by the end, when their heist comes together, does the viewer feel included in their unspoken code—a detail that makes rewatches so rewarding.

Though many Hollywood movies before Ocean’s Eleven had represented Las Vegas as a place operated by mobsters and populated by criminals who enforce their power with bloody violence and use the surrounding desert to bury their bodies—in films such as The Godfather (1972), Bugsy (1991), Casino (1995), and Hard Eight (1996)—Soderbergh’s film eschews violence. Rather, there is only the promise of it, and Garcia’s performance leaves the viewer with a palpable sense of danger, recalling the humorless austerity of a caricatured 1940s gangster—the kind where he gives the phone a long look before hanging up. After the heist, Benedict talks to Rusty over the phone and delivers a promise of retribution: “Run and hide… If you should be picked up buying a $100,000 sports car in Newport Beach, I’m going to be supremely disappointed. Because I want my people to find you, and when they do, rest assured we are not going to hand you over to the police.” Aside from implanting a sense of dread with a character more interested in a boxing match than a Picasso, the line further underscores Benedict’s association with the aforementioned Wynn, whose daughter was kidnapped in 1994. The specific references allude to the Wynn kidnappers, who were caught in Newport Beach while trying to buy a Ferrari with his cash. But Danny and his team remain nonviolent, and Soderbergh seems to admire them for that.

Though many Hollywood movies before Ocean’s Eleven had represented Las Vegas as a place operated by mobsters and populated by criminals who enforce their power with bloody violence and use the surrounding desert to bury their bodies—in films such as The Godfather (1972), Bugsy (1991), Casino (1995), and Hard Eight (1996)—Soderbergh’s film eschews violence. Rather, there is only the promise of it, and Garcia’s performance leaves the viewer with a palpable sense of danger, recalling the humorless austerity of a caricatured 1940s gangster—the kind where he gives the phone a long look before hanging up. After the heist, Benedict talks to Rusty over the phone and delivers a promise of retribution: “Run and hide… If you should be picked up buying a $100,000 sports car in Newport Beach, I’m going to be supremely disappointed. Because I want my people to find you, and when they do, rest assured we are not going to hand you over to the police.” Aside from implanting a sense of dread with a character more interested in a boxing match than a Picasso, the line further underscores Benedict’s association with the aforementioned Wynn, whose daughter was kidnapped in 1994. The specific references allude to the Wynn kidnappers, who were caught in Newport Beach while trying to buy a Ferrari with his cash. But Danny and his team remain nonviolent, and Soderbergh seems to admire them for that.

Soderbergh has never been a filmmaker interested in depicting violence on the screen, and Ocean’s Eleven involves characters smart enough to avoid shootouts and real guns. This is essential in a heist movie, where protagonists who resort to violence may alienate the audience. So, when they carry out their robbery, it’s not a “smash and grab” job, as Linus suggests in a quip lost on the room. Nor does it resemble the three “most successful” casino robberies in history, as described by Reuben, each propelled and resolved with sharp, unthinking violent acts—including a scene of guards who stop an unarmed ’80s thief by shooting him in the back. Rather, Soderbergh delivers an alternative to the standard Hollywood template of resolving conflict with violence, and the film associates violence with the Las Vegas establishment, the Terry Benedicts who deploy violence in hostile casino takeovers and backroom beatings. Griffin admitted in his commentary on the Blu-ray, “I’m not a big fan of shooting guns”—a curious remark for the writer of the cannibal horror-comedy Ravenous (1999), but no matter. As for Soderbergh, although exceptions do occur in the director’s career, such as 1999’s The Limey, his Ocean’s films value characters who restore order to power dynamics by relying on their wits and creativity, while characters who would resort to violence and intimidation are seen with a critical eye.

Much of what makes Ocean’s Eleven such a pleasure is the feeling that we’re part of Danny’s crew but also part of the cast. There’s a vicarious sense that everyone is having fun making this movie, wearing fine clothes, staying in swanky Las Vegas hotel rooms, and enjoying the many luxuries the city has to offer. Before the film’s release, the production led to behind-the-scenes entertainment news stories about the actors working for scale to keep costs down but then spending their off-hours enjoying the Vegas nightlife. Clooney was said to have blown his salary on gambling and drinks, including a keg of Guinness installed in his hotel room. The casual atmosphere reported from the set enriches the on-camera result, enhancing the chemistry among performers who clearly enjoy each other’s company. The onscreen wisecracks seem to be delivered with a half-smile, keeping the mood light and airy—a necessary component that helps gloss over some confusing details in the otherwise ludicrous plot. Take when the team’s gophers, the Mormon brothers, leave their fake hotel uniforms in the elevator after a costume swap to security garb. Won’t someone find the discarded uniforms and ask questions?

In any case, the film marked the first project developed by Section Eight, the production company founded by Soderbergh and Clooney in 2000. Started in the spirit of independent and artist-driven mainstream cinema that defined the late 1990s, Section Eight sought to champion daring filmmakers, such as Christopher Nolan (Insomnia, 2002), Todd Haynes (Far From Heaven, 2002), and Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly, 2006). Ocean’s Eleven was intended to start the company with a hit, enlisting an all-star cast who agreed to work for reduced salaries. Clooney and Soderbergh had no pretensions about their film’s status as a commercial enterprise. The ER actor told The Guardian, “Entertainment’s a good thing and I don’t think it’s something to be ashamed of.” Sure enough, the film would earn over $450 million worldwide, along with mostly positive reviews and enthusiasm from moviegoers. Years later, after several flops at Section Eight—Ocean’s Eleven and its two sequels would be some of its only significant earners—the company resolved to shut down, with Soderbergh more invested in directing than becoming a name-brand producer in the vein of Steven Spielberg in the 1980s.

In any case, the film marked the first project developed by Section Eight, the production company founded by Soderbergh and Clooney in 2000. Started in the spirit of independent and artist-driven mainstream cinema that defined the late 1990s, Section Eight sought to champion daring filmmakers, such as Christopher Nolan (Insomnia, 2002), Todd Haynes (Far From Heaven, 2002), and Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly, 2006). Ocean’s Eleven was intended to start the company with a hit, enlisting an all-star cast who agreed to work for reduced salaries. Clooney and Soderbergh had no pretensions about their film’s status as a commercial enterprise. The ER actor told The Guardian, “Entertainment’s a good thing and I don’t think it’s something to be ashamed of.” Sure enough, the film would earn over $450 million worldwide, along with mostly positive reviews and enthusiasm from moviegoers. Years later, after several flops at Section Eight—Ocean’s Eleven and its two sequels would be some of its only significant earners—the company resolved to shut down, with Soderbergh more invested in directing than becoming a name-brand producer in the vein of Steven Spielberg in the 1980s.

Shooting under his usual cinematographer pseudonym, Peter Andrews, the director achieves authenticity with real Las Vegas locations. His combination of a genuine setting and stylistic control, which blends realism with the director’s signature low-key visual polish, also lends Ocean’s Eleven an element of relaxed coolness. Elsewhere, David Holmes’ alternately jazzy and funky music gives the film a casual, easygoing tone, echoing his similarly groovy scores in many other Soderbergh features, including several heist stories: Out of Sight; Joe and Anthony Russo’s Welcome to Collinwood (2002), which Soderbergh produced under Section Eight; the two Ocean’s sequels in 2004 and 2007; Logan Lucky (2017), the Southern-fried version of Ocean’s; and No Sudden Move (2021), where a heist exposes corruption in the auto industry. But Holmes’ slick crime movie music breaks after the heist, when “Clair de Lune” by Claude Debussy plays while Tess runs across the casino to reunite with Danny, and the ten remaining thieves assemble at the iconic Bellagio fountain. The gentle music may break the cool mood, but it reimposes the themes of solidarity, camaraderie, and personal codes against Benedict’s moneyed interests. After Soderbergh’s camera pans across the faces of Ocean’s crew, who improvise their final moments together in this scene, Debussy’s music highlights the surprising yet effortlessly established bonds established among these characters and the viewer.

Despite starting one of the director’s two mainstream trilogies (next to the Magic Mike series) and easily his most commercially successful picture to date, Ocean’s Eleven aligns with Soderbergh’s longstanding interest in packaging institutional critiques into genre entertainment. These include harsh appraisals of the government’s response to drugs (Traffic), environmental oversight (Erin Brockovich), Big Corn (The Informant!, 2009), disease prevention and control (Contagion, 2011), the business of mental health (Side Effects, 2013; Unsane, 2018), tax evasion by the wealthy (The Laundromat, 2019), and the auto industry (No Sudden Move). Though made for tens of millions and starring a rather stunning cast, Soderbergh and Griffin somehow make the production feel modest, if not almost like an indie, in its ambition to undermine the multinational mindset dominating world economics. And so, just like its characters, the film is shimmering fun and subversive, defying the corporate interests of Benedict and Hollywood that, in one way or another, worship money above all else. With unchartable cool and control, Danny and company steal that money, deliver a blow to the establishment, and remain faithful to their code and each other. Their brand of friendship and Danny’s ultimate goal, motivated by love, turn them into cathartic heroes in an age that continues to be dominated by corporate interests.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on June 7, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Andrew, Geoff. “Interview: Steven Soderbergh and George Clooney.” The Guardian, 17 February 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2003/feb/17/features.georgeclooney. Accessed 30 May 2023.

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

“Commentary by director Steven Soderbergh and screenwriter Ted Griffin.” Ocean’s Eleven, Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 2007. Blu-ray.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review