The Definitives

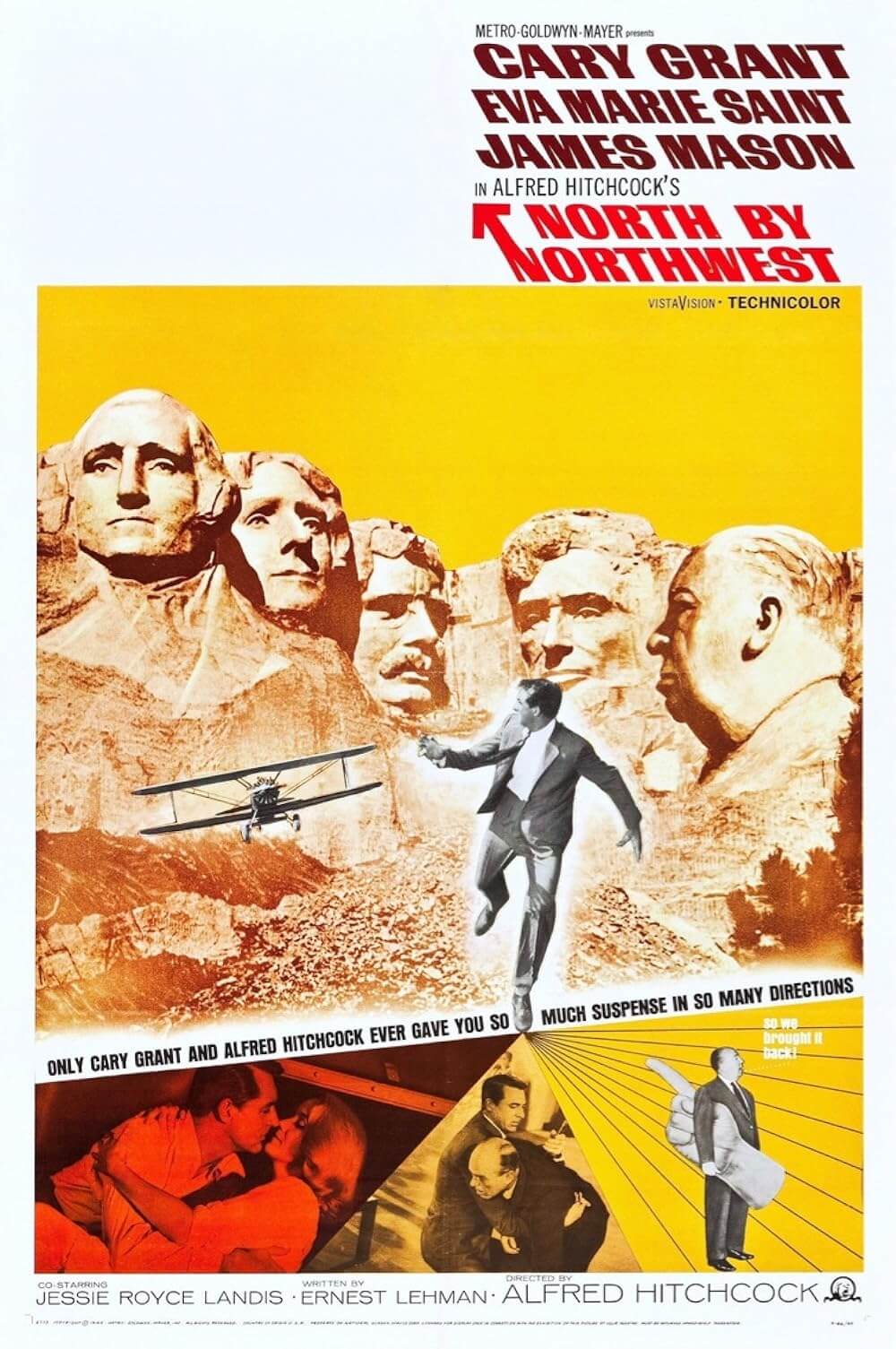

North by Northwest (1959)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

North by Northwest distills Alfred Hitchcock’s obsessions, techniques, and themes into a singular, deliriously entertaining form. The legendary Master of Suspense piles a career’s worth of preoccupations and storytelling devices into his 1959 motion picture, an escapist yarn like no other, except others by Hitchcock. Teeming with a wrongly identified hero, played by the filmmaker’s model leading man Cary Grant no less, an icy blonde, a gripping Bernard Herrmann score, a monumental finale, and the most wonderfully transparent of all MacGuffins, the film embraces and augments the director’s long-standing narrative and formal elements into the ultimate comic thriller. This is escapism at its best, arranged to stimulate the viewer and carry them from one dazzling moment to the next. The plot itself makes leaps and bounds that, when charted in an overall progression from scene to scene, make little sense and require extraordinary suspension of disbelief. And yet, somehow, it all works so effortlessly. Hitchcock’s method involves his audience on a raw emotional level, as opposed to an intellectual plane. While Grant’s undeniable charms and screenwriter Ernest Lehman’s sharp dialogue keep the audience blind to the director’s scheme, Hitchcock orchestrates a nonstop procession of memorable sequences, brimming sexuality, and breathless fun.

North by Northwest is about this moment of viewership. Its individual scenes offer suspense, intrigue, and humor, along with a feeling of intensity and a connection to the characters, but not overall participation in the overarching story. Indeed, the very root of the film is about nothing at all. Hitchcock savors the plot’s misleading nature, and by extension, the story’s hollowness underscores his role as a master manipulator—his ability to conjure a reaction from the viewer out of thin air. The story begins with a mistaken identity, introduces a spy device of vague government secrets landing in the wrong hands, proceeds with illogical turns and impossible happenstance, and ends without onscreen resolution of the central conflict. No believable motivation links these major developments, except the marvelous way in which the director presents them. What we remember about the film are impressions and feelings, moving visuals or bravado sequences, a romantic yearning, and the magnetism of the well-tailored Grant. We are less confident about our understanding of the plot. But that Hitchcock maintains his audience’s devoted interest, and even leaves us feeling incredibly fulfilled by the time the credits roll, attests to his ability to manipulate us.

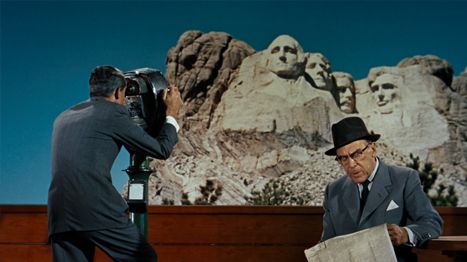

The inspiration for North by Northwest started with one Otis Guernsey, a theater critic for the New York Herald Tribune. While at the 21 Club with Hitchcock in 1951, Guernsey pitched a scenario to the director about a salesman mistaken for an imaginary secret agent. It was a familiar idea; going back to The Lodger (1927), Hitchcock had made several thrillers about men in the wrong place at the wrong time. Years later, Hitchcock and writer Ernest Lehman talked over several weeks to discuss ideas for a possible collaboration. During one of their dinners, Lehman told the director, “I want to do a Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures. That’s the only kind of picture I want to do.” Lehman wanted to make what he called, “A movie-movie, with glamour, wit, excitement, movement, big scenes, a large canvas, innocent bystander caught up in great derring-do, in the Hitchcock manner.” They began toying around with a thriller set into motion by a murder at the United Nations. Hitchcock proposed adding Guernsey’s concept, along with another idea he had been toying with for years—a chase on Mount Rushmore. Lehman was delighted by these springboards and, in 1957, started writing what he hoped would be the definitive Hitchcock picture, consciously incorporating themes from throughout the director’s oeuvre. The writing process would take over a year of story conferences and debates between Lehman and Hitchcock; meanwhile, the director went off to make Vertigo (1958) for Paramount.

Production on North by Northwest began in 1958, although it was not yet known by that name at MGM. The filmmakers gave their production various titles, including In a Northwesterly Direction, The Man on Lincoln’s Nose, and Breathless. The title they eventually settled on made little sense to the cast and crew since the direction “north by northwest” does not exist on any compass. Hitchcock points out that, at one point, the film’s falsely accused protagonist, New York advertising man Roger O. Thornhill (Grant), travels up from Chicago to South Dakota via Northwest Airlines. But it remains an unsatisfying explanation if the title is merely a directional reference, combined with a ham-handed airline plug. Consider an alternative possibility: that Hitchcock meant to wink at Shakespeare, quoting Hamlet’s lamentation of his growing madness: “I am but mad north-north-west. When the wind is southerly I know a hawk from a handsaw.” After all, the film’s protagonist falls into trouble and cannot make heads or tails of the spiraling circumstances in which he finds himself. And so this Shakespearian allusion gives the title some meaning, even though the director later denied any intended reference.

From the outset, the film materializes out of nothingness. A case of mistaken identity propels the plot, but the identity is a false one—created by the FBI as a decoy set to protect their real agent. Thus, when Cold War spies grab Thornhill, believing him to be undercover agent George Kaplan, he’s the wrong man, even though there’s no right man. When they kidnap him, Thornhill insists they have made a mistake. But his denials are “just as obvious” as other spies they have captured and killed. When he fails to cooperate and give them information, their sinister boss (James Mason), going by the name Townsend, orders them to kill the would-be Kaplan by filling him full of alcohol and placing him behind the wheel of a car on a winding cliffside road. Thornhill escapes by way of some expert drunk driving. After a night in jail, Thornhill returns to Townsend’s home with the authorities, but his kidnappers have planned an elaborate cover story. Thornhill then sets out to find Townsend, whom he learns will be appearing at the United Nations general assembly. When he confronts Townsend, who is not the man he met the night before but the real Townsend (Philip Ober), he quickly finds himself framed for murdering the United Nations official and on the run from authorities. Not only is he the wrong man wanted by Mason’s Phillip Vandamm, but now he’s the wrong man in a murder with his picture on the front page. What else can Thornhill do except hop a train to Chicago to find the real George Kaplan?

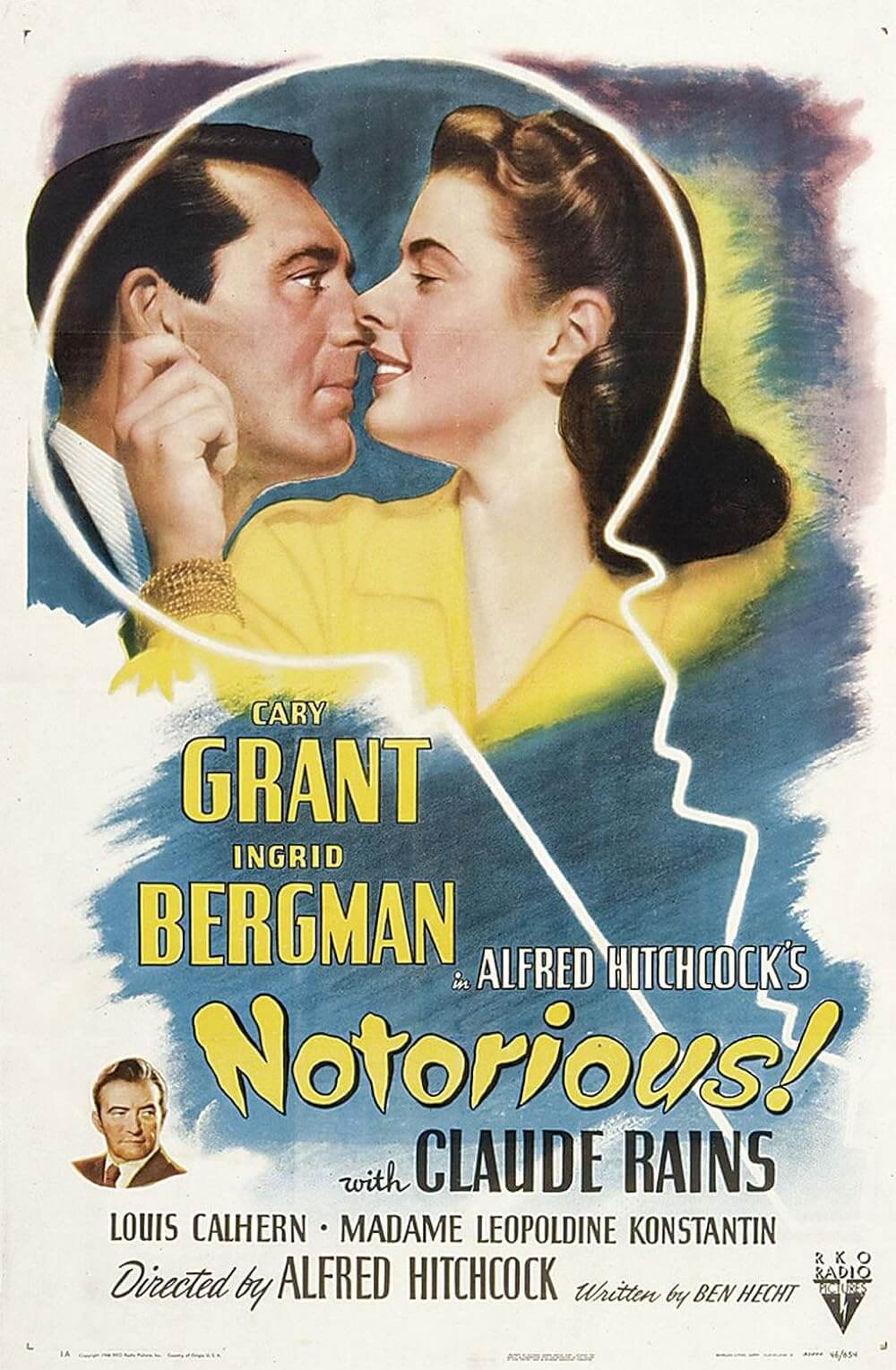

North by Northwest is propelled by nonentities. Thornhill’s race to clear his name hinges on two questions: Who is George Kaplan, and what is Kaplan trying to prevent Vandamm from acquiring? There’s no straight answer to either question. Kaplan is a fictional diversion, and the viewer never learns the contents of the microfilm that Vandamm hopes to sneak out of the country, presumably for the Soviets. Similar Hitchcock plot contrivances have included a wine bottle filled with uranium in Notorious (1946), the rope used to strangle someone in Rope (1948), and the stolen cash in Psycho (1960). They also take intangible forms, such as the formula kept by Mr. Memory in The 39 Steps (1935), the code stored in Ms. Foy’s tune in The Lady Vanishes (1938), or the confession of a murderer withheld by a priest in I Confess (1953). Realizing that each of his films relied on such a device, Hitchcock adopted the term “MacGuffin” to describe it. He explained the concept to François Truffaut in their seminal 1966 interview:

It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men in a train. One man says, ‘What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?’ And the other answers, ‘Oh that’s a MacGuffin.’ The first one asks ‘What’s a MacGuffin?’ ‘Well,’ the other man says, ‘It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ The first man says, ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,’ and the other one answers ‘Well, then that’s no MacGuffin!’

In North by Northwest, the MacGuffin is reduced to what Hitchcock called “its purest expression: nothing at all!” The information sought by both Thornhill and the government is stored on microfilm contained within a figurine. But the secrets on that microfilm, thus the gravity of the stakes, are never revealed. The information pursued by American agents and crooked spies, with everyman Cary Grant caught in the middle, means nothing once the audience is rapt by the swelling tension. The same events could be written around the pursuit of stolen diamonds, a priceless work of art, a bomb, or a doomsday device. The specifics have no substance. In essence, the passages to obtain the thing are what matter most, whereas the particulars of why and for what could not be less significant. Realizing that the MacGuffin of North by Northwest was perhaps his finest manipulation of his audience, Hitchcock boasted to Lehman: “Do you realize what we’re doing in this picture? The audience is like a giant organ that you and I are playing. At one moment, we play this note on them, and get this reaction. And then we play that chord and they react that way.”

The theme that North by Northwest revolves around a vague idea is alluded to with the name Roger O. Thornhill. On the train to Chicago, where he hopes to find George Kaplan, Thornhill meets a flirtatious Good Samaritan, Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), whose willingness to harbor a fugitive for the entire journey is motivated by her seeming loyalty to Vandamm. Eve asks Thornhill what his middle initial stands for. “Nothing,” he replies in a pointed reflection of his own shallow personality. Still, this nothingness, analogous to the film’s MacGuffin, is essential to a character whose wit and allure provide Cary Grant with his most charismatic role. Every line of Lehman’s quick dialogue finds Grant at his prime, and his gray-blue Glen plaid suit, often considered the greatest suit ever captured on film, certainly doesn’t hurt his effect on the viewer. Much has been written about the effect of Grant’s wardrobe in the film. Writer Todd McEwan’s short story, “Cary Grant’s Suit” from 2006 retells the film’s story from the suit’s perspective, beginning with the line, “North by Northwest isn’t a film about what happens to Cary Grant, it’s about what happens to his suit.” Even so, Grant’s entire persona defines the cipher of Roger O. Thornhill. He made such an impression that author Ian Fleming, along with producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli, named Grant as their first choice to play James Bond when they began development on Dr. No (1962).

Nevertheless, James Stewart was the first name mentioned to play Thornhill when Hitchcock began the demanding process of casting North by Northwest. A longtime collaborator on films like Rear Window (1954), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), and Vertigo (1958), Stewart was occupied making Bell Book and Candle, a light romantic comedy opposite Kim Novak. But that served as a relief to Hitchcock, since only the suave and eternally youthful Cary Grant, with his tanned skin and Mid-Atlantic accent, could play Thornhill and make the role a significant one. Moreover, the director attributed Vertigo’s commercial failure to Stewart’s visibly increasing age, and he dreaded the possibility of rejecting the actor on those grounds. Luckily Grant, though teeter-tottering on retirement, signed to play Thornhill. He negotiated a lucrative deal, too, including a $450,000 fee and a sizable share of the profits for his performance, plus a fee for every day the film went over its scheduled completion date, which was plenty.

However, Grant raised questions about his role in the film after signing—a trend that Hitchcock had become accustomed to over their many collaborations. Ever since Suspicion (1941), the film where Grant signed on to play a murderer but was rewritten into a misunderstood gambler, the actor had doubts about working with the director. But Hitchcock knew the easiest way to overcome Grant’s protests was to ignore them. He did just that, and they subsided. Grant’s relationship with Hitchcock had always been rocky, but not problematically so; it never prevented them from having a productive relationship. Availability and budget restraints often foiled their potential collaborations, but Hitchcock always envisioned his leading men with Cary Grant in mind—an attractive, well-dressed, and quick-witted hero who is desirable to beautiful women and nimble enough to outsmart the opposition. Despite Hitchcock’s high regard for Grant, the two only collaborated on four pictures, including Notorious and To Catch a Thief (1955). And so, while Grant remained baffled by Lehman’s improbable scenario, criticizing the lack of logic from scene to scene, Hitchcock wanted Grant that way—it reflected how the bewildered Thornhill should feel wrapped up in a tangled web of spies.

Although the director first approached the newly crowned Princess Grace (Kelly) to play Eve, MGM wanted Cyd Charisse for the Mata Hari role. Hitchcock settled on an unlikely blonde, Eva Marie Saint, who had won an Oscar four years prior for On the Waterfront (1954). She would follow the long line of elusive Hitchcock blondes, all placed in distress, requiring a male hero to save them. Grace Kelly embodied that role in Dial M for Murder (1954), To Catch a Thief, and Rear Window; Tippi Hedren in The Birds (1963); Janet Leigh in Psycho; Kim Novak in Vertigo—the list goes on. Like all his blondes, the director went to great lengths to assure Saint looked beautiful in every scene, using precise wardrobe choices and lighting to achieve the effect, as well as treating her like royalty off-camera to affix her own self-image. She was instructed to lower her voice, avoid using her hands, and look directly at Grant in her scenes opposite him. As coached by Hitchcock, these details helped form Saint’s appealing yet pointedly distant onscreen persona. That her character must remain enticing and mysterious to preserve her double-agent guise makes Eve the decisive Hitchcock blonde. The role necessitates what would otherwise be Hitchcock’s fetishist traits: She appears outwardly demure yet has sex on the mind, she is strong-willed and yet needs to be rescued, and she’s not afraid to hop into bed with Grant.

In their scenes together on the train to Chicago, Grant and Saint share delightful passages of Lehman’s clever, sexy dialogue. Seated across from each other in the dining car, the conversation quickly moves into a playful exchange of innuendo. “I tipped the steward five dollars to seat you here if you should come in,” Eve tells him. “Is that a proposition?” Thornhill asks. She declares, “I never discuss love on an empty stomach.” “You’ve already eaten.” “But you haven’t.” The audience loses themselves in this romantic banter, forgiving how easily these strangers leap into each other’s arms, certainly not suspecting Eve’s double-cross yet. Allowing the fugitive Thornhill into her compartment where they become close, Eve asks, “How do I know you aren’t a murderer?” “You don’t,” he replies. “Maybe you’re planning to murder me right here, tonight,” she suggests. “Shall I?” “Please do.” And then they kiss. This scene mirrors the one in Notorious between Grant and Ingrid Bergman, what was then called the longest screen kiss ever put on film, yet the dialogue in that scene breaks up a dozen smaller kisses, just like this one. Lehman, the writer of Sabrina (1954) and Sweet Smell of Success (1957), layers every scene with double meanings and suggestive overtones; dissecting it proves just as thrilling as the spy-themed suspense.

Elsewhere in the cast, the ever-suave James Mason plays the villain, Vandamm, a courier of top-secret intelligence. Mason, as the characters in Hitchcock’s Rope remarked, is “attractively sinister” and manages to be at once despicable and devilishly charming. Hitchcock’s villains have a way of doing that—just look at Claude Rains as the charismatic Nazi from Notorious. Mason’s presence comes through, even though on-set he felt like another one of the “animated props” that Hitchcock called actors. Vandamm’s right-hand-man, Leonard, played by Martin Landau, was accused of having a “flavor of homosexuality” by censors, but no changes were made to adjust their interpretation. Leonard, who reveals his jealousy over Vandamm’s affection for Eve within a few subtle gestures, admits his suspicion of her. He calls it his “woman’s intuition.” Alas, Leonard is another of Hitchcock’s queer-coded characters in a villainous role, following Rober Walker’s murderer in Strangers on a Train (1951) and the two young killers in Rope. The last major addition to the cast was Jesse Royce Landis, who plays Thornhill’s mother. The actress was almost a year younger than Grant at the time, and though she may not look it, her blithe and sarcastic character behaves as much.

Shooting scenes of violence and espionage in iconic locations became a predictable hurdle for North by Northwest. United Nations officials denied Hitchcock permission to shoot an assassination sequence at the New York headquarters. But the director refused to concede so easily. He placed cinematographer Robert Burks inside a covert carpet-cleaning truck to sneak an exterior shot of Grant approaching the entrance. For the accurate interiors by production designer Robert Boyle, Hitchcock and a still photographer posed as tourists to steal some photos of the inner building. The Department of Interior officials in charge of Mount Rushmore presented Hitchcock with another set of problems in Rapid City. They limited Hitchcock’s crew by cutting their shoot time to two days and confining their cameras to the cafeteria and parking lot. This was more than enough for Hitchcock, who captured enough still photographs for Boyle to create the interiors on Hollywood sets. Finally, the director wanted Cary Grant to slide down Lincoln’s nose, hide in his nostril, and then suddenly have a sneezing fit. But the landmark’s authorities would not allow Grant to appear on the actual faces of the monument’s past presidents, or even Boyle’s duplications, only between the faces to preserve the integrity of the nation’s most venerated figures. The sneezing gag was eventually scrapped.

Choosing these landmarks was a conscious choice on Hitchcock’s part to imbue murder and suspense with the iconography of a well-known landscape or national monument. The United Nations and Mount Rushmore were easily identifiable locales, and Hitchcock used that to twist them into something macabre or fantastic. He enlivened these locations, just as he did on several other pictures featuring landmarks. In Saboteur (1942), the villainous spy is dropped to his death off the Statue of Liberty; Vertigo features a woman leaping into San Francisco Bay in an attempted suicide, the Golden Gate Bridge looming in the backdrop; Dutch windmills play a key role in Foreign Correspondent (1940); the entire French Riviera has a pivotal part in To Catch a Thief. With North by Northwest, Hitchcock delivers his most monument-heavy picture of them all; though, he also ensured his settings were entirely functional within their scenes and avoided superfluous action. For instance, the director had hoped to shoot a sequence where Thornhill speaks with the foreman of a Ford factory in Detroit. He described the proposed scene to Truffaut: “Behind them a car is being assembled, piece by piece. Finally, the car they’ve seen being put together from a simple nut and bolt is complete, with gas and oil, and all ready to drive off the line […] Then they open the door to the car and out drops a corpse!” Although Hitchcock and Lehman could not work the sequence into the script, Steven Spielberg realized a version of the same idea in his own wrong-man thriller, the sci-fi masterpiece Minority Report (2002).

For the film’s crop duster chase in an empty farm field, Hitchcock went into great detail to construct one of cinema’s most memorable scenes. After narrowly escaping capture on the train to Chicago, Eve points Thornhill to a bus stop some 90 minutes outside of the city, where she claims Kaplan has agreed to meet him. Thornhill arrives and waits on an empty road. There’s nothing to see besides the vast fields, shot in glorious VistaVision by Burks, reaching into the distance. Herrmann’s propulsive score has gone silent. The occasional car passes by. Far away, a crop duster fertilizes a field. Minutes pass before a car pulls out from a dirt road and drops off a man, not Kaplan. “That’s funny,” observes the man. “That plane’s dustin’ crops where there ain’t no crops.” Hitchcock makes the audience aware of the plane and the setting’s open isolation long before anything happens. Alone again, Thornhill notices the crop duster coming toward him. It begins to attack, diving and shooting machine gun rounds. He runs and ducks as it continues to lunge, and then he hides in a nearby cornfield. All at once, he dashes to wave down an approaching tanker. The driver slams on his breaks and nearly flattens our hero. The crop duster makes its last advance, and it crashes into the tanker, inciting an explosion.

Following the notion that North by Northwest is driven by empty vessels, Hitchcock once proclaimed that the plane and who was flying it mattered not, “So long as the audience goes through the emotion.” As Grant runs from the plane approaching him, still looking composed despite his sprint, the audience goes through whirling emotions as the scene crescendos. Hitchcock added this magnificently gratuitous scene just for the sake of exploring the antithesis of thriller cliché. He does the opposite of those typically claustrophobic scenes in thrillers, where, in the dark of night, the killer stalks his prey into a tight alleyway. By contrast, Hitchcock gives Thornhill a wide-open space to maneuver, in broad daylight no less, but also gives him nowhere to go. Assembled through bravado editing, the sequence, one of the most splendidly thrilling in the history of motion pictures, comes from Hitchcock’s ingenious blend of filmmaking technologies. A combination of location footage and matte paintings set the scene. Barely any dialogue is spoken for nearly seven minutes. The plane dives about the landscape. The star runs toward the camera; doubles run away from it. Some scenes are shot on location, others on an MGM soundstage. Bits and pieces come together to make a fluid montage, rivaling Hitchcock’s shower scene in Psycho. The sequence is what the director called “pure cinema.”

Another iconic quality of North by Northwest is Bernard Herrmann’s score. Herrmann’s career as a film composer had begun long before his famous partnership with Hitchcock. Having arranged music for Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre broadcasts, he followed Welles into the realm of cinema beginning with Citizen Kane (1941), followed by Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Herrmann, who won an Oscar for his work on William Dieterle’s The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), scored a total of seven Hitchcock films, beginning in 1955 with The Trouble with Harry. Herrmann even oversaw the sound design for The Birds, though that film has no actual score. For North by Northwest, the composer sustains the picture’s momentum from the outset, revamping a Spanish dance, the Fandango, for the main theme. Hitchcock trusted Herrmann implicitly, never interfering with his process; the results produced some of cinema’s most unforgettable scores, and this film’s music belongs near the top of that list.

Regardless of such heart-stopping thrills and memorable music, the Production Code wagged its finger at the film’s sexuality. They raised concerns about Thornhill boasting about his many divorces, the implicitly sexual overnight train-compartment liaison between Thornhill and Eve, and some of the dialogue. The original line “I never make love on an empty stomach” became “I never discuss love on an empty stomach,” thanks to none-too-subtle ADR. Still, Hitchcock got away with plenty. The film’s famously suggestive final scene shows the train entering a tunnel in an unquestionably sexual image, the cinematic equivalent of a lewd bathroom stall cartoon. By leaving it to the Production Code office to point out the symbolism, Hitchcock, in turn, took it out of their hands. Censor Geoffrey Shurlock wanted the moment before this locomotive penetration to include a line where Thornhill says to Eve, “Come along, Mrs. Thornhill,” thus suggesting their marriage. The line was dubbed in after filming had wrapped, much to the satisfaction of Shurlock, who was apparently none the wiser about the visual innuendo that immediately followed it. Not since Ernst Lubitsch had such an explicit illustration of the underlying sexual meaning been approved by the Production Code Administration.

The final visual ingredient added to North by Northwest appears at the beginning: Saul Bass’ animated title sequence. The slowly wrapping production had cost $1.3 million more than the originally estimated $3 million budget, given that the shoot (and retakes) had taken longer than expected. Bass’ titles came about when the over-budget and behind schedule production had no remaining time or money to complete Hitchcock’s intended opening—a chain of scenes that set up Thornhill as an ad man—though Grant was willing to shoot the sequence free of charge. Just the time and equipment would have cost more than MGM was willing to spend. Instead, Bass conceived a slanted graph, which slowly builds momentum in tandem with Herrmann’s hurtling score, and eventually constructs the skyscraper of the film’s first live-action shot. As with all of the designer’s work, which includes the opening of Psycho and the animated sequences in Vertigo, his concept was simple, dynamic, and in due course, iconic. Immediately following it, a montage of city scenes takes us through the remaining credits, ending with Hitchcock himself missing a bus in one of his ever-present cameos.

North by Northwest earned Hitchcock some the best reviews of his Hollywood career. Writing in The New York Times, critic A.H. Weiler remarked that the film’s elements were “all done in brisk, genuinely witty and sophisticated style” and called it “the year’s most scenic, intriguing and merriest chase.” Critic Charles Champlin recognized the film as an “anthology of typical Hitchcockian situations,” while The New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett similarly observed the director’s “perfect parody of his own work.” Audiences flocked to see another pairing of Grant and Hitchcock, the latter of whom had become a household name—a rarity among directors at the time. Given his careful control of his public image and brand, Hitchcock’s celebrity had reached its height, powered by his televised anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965). North by Northwest earned nearly $10 million in box-office receipts, what today would amount to a major blockbuster. It also received three Academy Award nominations for Best Editing, Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, and Best Screenplay. Since its release in 1959, it has only continued to bloom, earning spots on the American Film Institute’s various “100 Years” lists—not to mention the prolonged appreciation of Grant’s suit.

Proving the adage that cinema consists of faces, places, and chases, North by Northwest is rooted in fabrication and nothingness. Any serious scrutiny of how its story comes together results in puzzlement. Questions of plot notwithstanding, the film can be used as a guidebook to identify common traits in Hitchcock films beginning with The Lodger, lasting through Saboteur, and ending with Frenzy (1972). A blonde in peril, a wrongly accused man, and national monuments all frequently appear throughout his career. But their purpose in the director’s earlier films was never to highlight their utter superfluousness as story elements; here, they emphasize the importance of the raw thrills and suspense, which only seem essential to the plot because its director has spun them that way. Although the film is an assemblage of familiar Hitchcockian components pieced together here and there in the structure of a twisting scenario—just as Lehman intended—something miraculous happens when the director puts those components together. Hitchcock told Truffaut that The 39 Steps summed up his British work, whereas North by Northwest epitomized his Hollywood films. To be sure, no other Hitchcock film amasses a series of otherwise unconnected ideas and ties them together so creatively to instill the impression of a tightly bound motion picture. That sort of illusory filmmaking, which despite being so plainly presented before the viewer’s eyes remains deceptively composed, is exactly what makes Hitchcock the master of his craft.

(This essay was originally published on November 19, 2009. It has been edited and expanded.)

Bibliography:

Krohn, Bill. Hitchcock At Work. Phaidon, 2000.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, c2003.

Modleski, Tania.The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. Routledge, 2006.

Petrie, Graham. Hollywood destinies: European directors in America, 1922-1931. Wayne State University Press, c2002.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. Cary Grant: A Celebration. Little, Brown, c1983.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. Atheneum, 1975.

Spoto, Donald, The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. Little, Brown & Co., 1983.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Žižek, Slavoj. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). Verso, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review