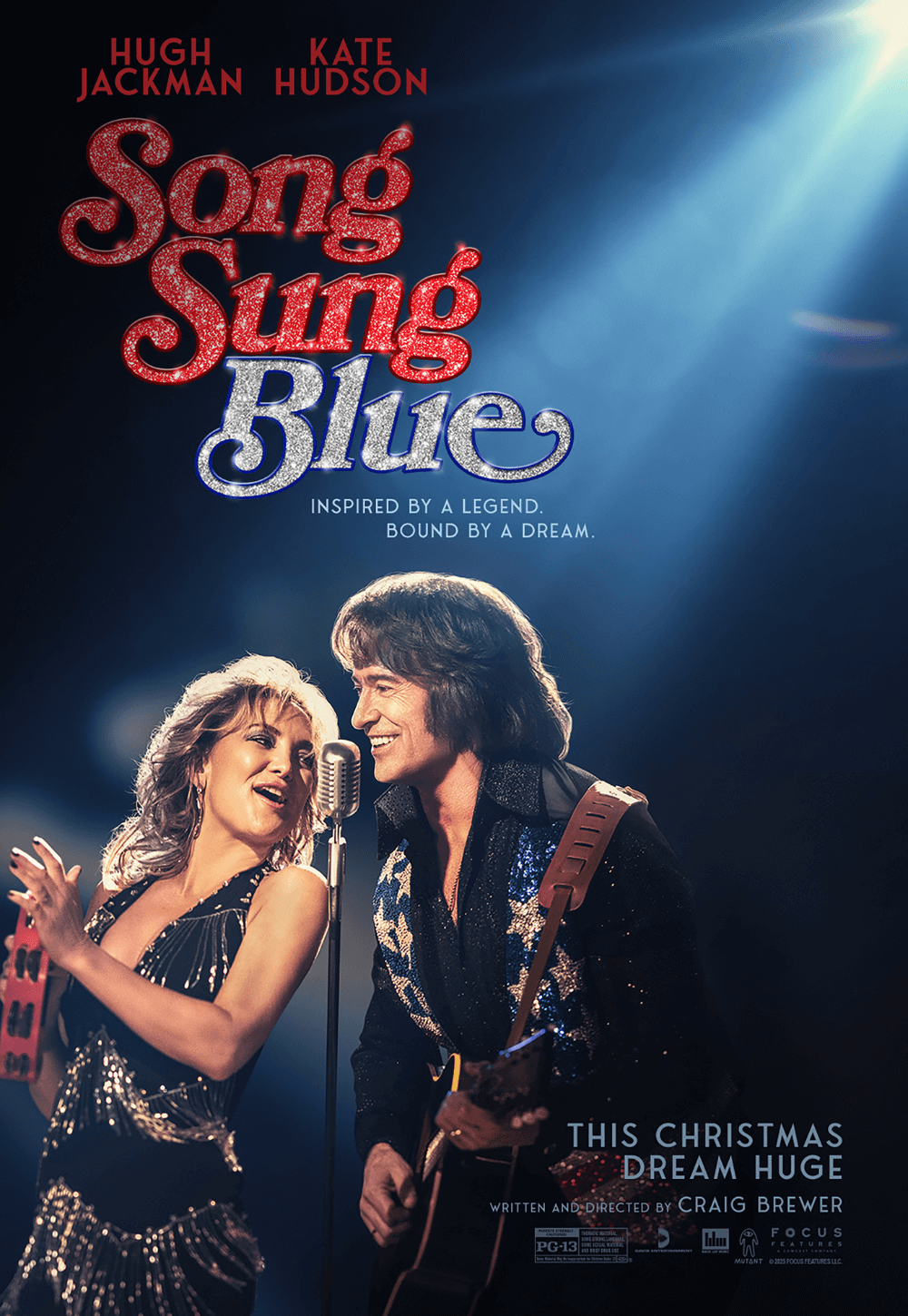

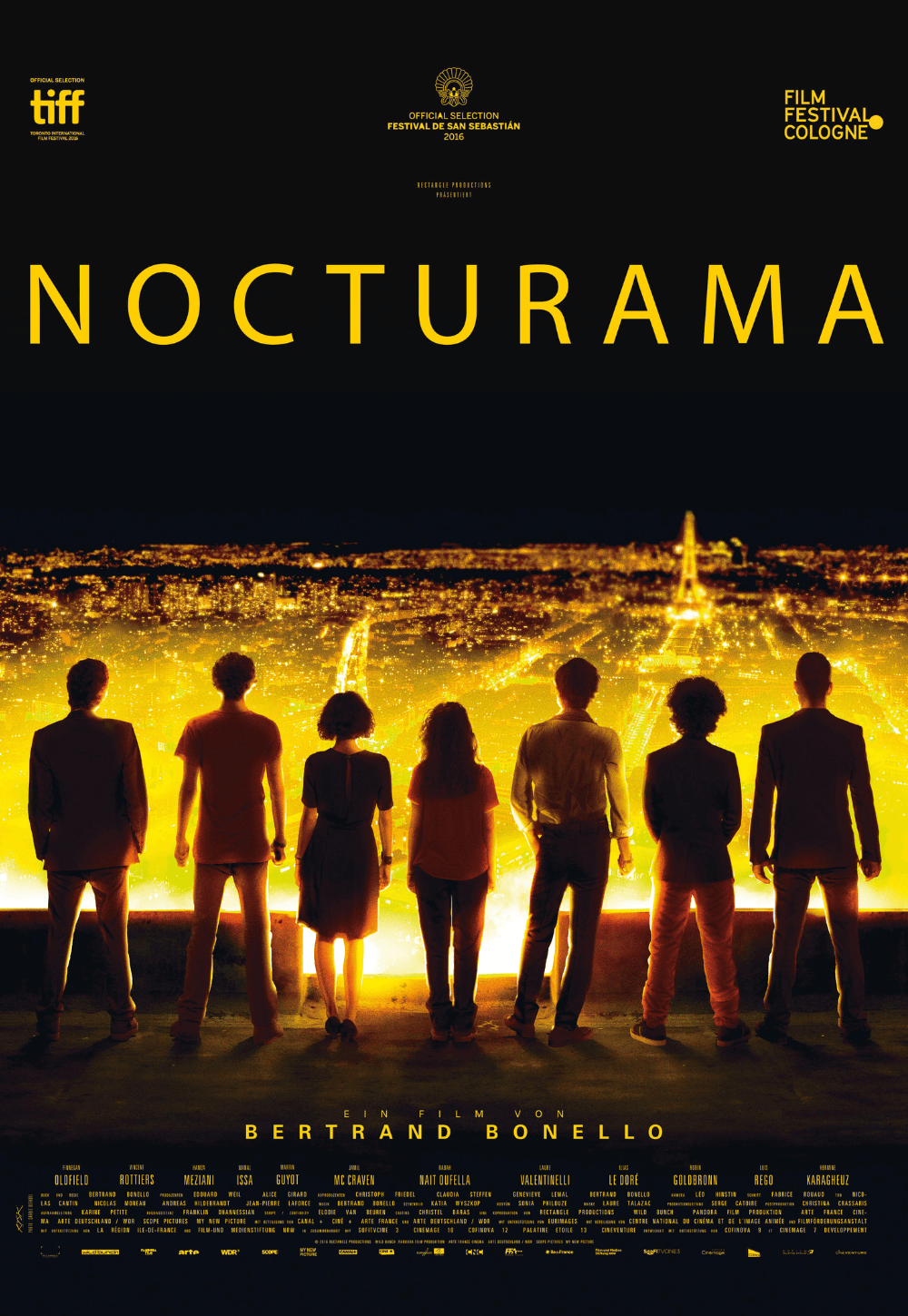

The Definitives

Nocturama

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama follows a band of guerillas who, in their youthful determination, coordinate several attacks on Paris landmarks. After, they retreat into a department store where, following many hours of idling, a police raid leaves them all dead. Bonello does not subscribe to the beliefs held by these toy soldiers acting in a revolution of misdirected idealism. He never catalogs their ideology beyond describing their state and capitalistic targets in the establishment. With equal measures of precision detail and abstraction, the 2016 film enters a dreamscape that is skewed with youthful passion and dubious intent, yet thrust by the initial certainty of propulsive action. Still, the question of Bonello’s specific artistic ambition lingers. Does he intend to exploit modern anxieties about political extremism in service of a thriller or make a statement about a political perspective? Neither, as it turns out, to polarizing effect. Nocturama is far more nebulous in its meaning than anything so straightforward, weighing history, aestheticism, and contemporary events in an esoteric package. Bonello’s characters have as much psychological depth as the mannequins displayed in the department store where they take refuge. His young terrorists have adopted an image and political philosophy like wearing a mask, covering their internal struggle with an artificial certitude. With this, Bonello does not construct a bomb-of-a-film but sets an intriguing, if often frighteningly beautiful minefield for his audience to navigate.

Activated by Bonello’s electronic score, the first half of Nocturama propels forward with urgent intention, marked by dynamic editing and the systematic progression of a process-driven thriller. Ten young Parisians, ranging in age from their teens to early twenties, with varying backgrounds, races, classes, and religions, who come from privileged homes and disenfranchised banlieues, carry out a precise plan to attack key targets in the French capital. Without dialogue for the first 20 minutes, the film intercuts between their precise and synchronous actions. It starts with a ponderous shot of Paris from above, peaceful and quiet, before descending to the dark underground Métro, moving with a singular momentum. The collaborators send codes on their burner phones and carry out an intricate schedule that involves getting off and on Métro cars, waiting in stations, and rendezvousing with their co-conspirators at appointed times. They exchange brief glances and avoid prolonged eye contact, walking intently to their next checkpoint and photographing random objects—a toilet, a cracked wall, etc.—to indicate their progress. The feverish, involving sequence follows their carefully arranged steps toward their purpose, scrupulously detailed by Bonello yet elusive and filled with dread over what little information he reveals about them or what, politically or otherwise, they hope to achieve.

While they move determinedly through modern spaces, Bonello follows the characters toward their final destination. Along the way, he establishes familiar faces with a minimum of dialogue and exposition. Thanks to his well-connected father, the preppy André (Martin Guyot) interviews for an internship with a government official at the Ministry of the Interior, and while there, helps sneak the boyish Mika (Jamil McCraven) inside to plant explosives. Sabrina (Manal Issa) nervously practices the lines she will say to a hotel clerk—presumably because she’s never checked into one before, and certainly not with a bogus credit card—with plans to access Emmanuel Frémiet’s 1874 statue of Jeanne d’Arc and apply an accelerant. Working with their inside man Fred (Robin Goldbronn), a security guard at the skyscraper headquarters of multinational bank HSBC, the young lovers David (Finnegan Oldfield) and Sarah (Laure Valentinelli) plant bombs on the higher floors. Brief flashbacks show the group learning about Semtex, a rare plastic explosive supplied by their older compatriot Greg (Vincent Rottiers), and they marvel over how 250 grams can blow up a jetliner. They are young but prepared.

The group’s efforts reveal an attack on what Bonello has described as “symbols of oppression” for his characters. Frémiet’s golden statue outside of the Place des Pyramides in Paris—a symbol often appropriated by right-wing political figures and fascist ideologies in France—bursts into flames. An explosion rocks the Ministry of the Interior, where French politicians oversee matters of internal security, immigration, and civil protection. Cars parked outside the Stock Exchange detonate as well, causing successive explosions amid other vehicles. Hector Berlioz’s Requiem, a mournful piece of music commissioned in 1837 by Adrien de Gasparin, the Minister of the Interior of France, to honor members of the Revolution, plays against Greg killing an HSBC executive. A high floor in the HSBC building, a symbol of capitalism, bursts in an image that evokes footage from the 9/11 attacks. Hiccups in their plan occur: A car strikes Mika in the street, resulting in a wounded arm; David appears to lose bladder control in the chaos; Fred kills a man on a phone, and then another security guard kills Fred. Otherwise, everything goes as planned, mostly.

Shot with rigorous detail in the clarity of daytime exteriors, Bonello characterizes the first half of Nocturama with measurables such as time and place, presented in schematic perspicuity. Echoing his subject, Bonello sets aside his customary, richly colored 35mm film stock for a flat digital presentation that seems to glide through every scene, following along with his characters on their mission. The director borrowed his technique from the minimalism of Alan Clarke’s Elephant (1989), where the camera observes 18 murders in Northern Ireland during the Troubles with procedural detail. It was later referenced by Gus Van Sant’s 2003 film of the same name, based on the 1999 Columbine High School shooting. However, the second half of Nocturama turns the schema inside-out when the characters shelter at a department store overnight to wait out the aftermath of their triumph. Day becomes night. Real open-air Parisian locations become an enclosed and artificial space, built in a studio by Bonello’s production team. Time comes to a standstill. Yet, their refuge of choice says as much about them as their film’s director.

Born on September 11, 1968, Bonello grew up in the aftermath of the May 1968 student revolt and worker protests, during an era of revolutionary change in response to President Charles de Gaulle’s policies. After rising to power in 1958 through unconventional means, following the disintegration of the Fourth Republic amid the Algerian War (1954–62), the staunchly conservative, traditionalist, and authoritarian de Gaulle was viewed as a social dictator. Incited by the massive French student population, the counter-culture protests of May ’68 launched a period of civil unrest, with student demonstrations, worker strikes, and occupations of universities and factories throughout France, challenging de Gaulle’s government in hopes of bringing about sociopolitical change to more liberal and progressive values. The protests worked, prompting de Gaulle to resign in 1969 and initiating several reforms, including wage increases, better working conditions, and new educational policies. While these ends justified the means of the protests from a historical perspective, Bonello was raised in the relative freedom of the 1970s and wake of the riots, understanding that the ’68 protesters had already fought the most meaningful fight. “You always have this kind of nostalgia for something you’ve not really known,” he told interviewer Ryan Akler-Bishop. He noted that others in subsequent generations felt similarly, itching for the same revolutionary victories.

In his youth, Bonello developed an appreciation for the arts from his parents, a lawyer and a worker in the Nice opera. He trained on the piano and explored music, headlining a teenage rock band before moving to Paris and working as a session musician. Dismayed by the state of the French pop music scene, Bonello switched to cinema after seeing Stranger Than Paradise (1984), directed by Jim Jarmusch, another musician who transitioned to filmmaking. But unlike many other directors, Bonello’s interest in film did not begin with a vigorous consumption of anything and everything at local movie houses. Rather, as he told Cinéaste in 2019, he followed the line of formal and political renegades such as Robert Bresson, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Eustache, and Leos Carax—filmmakers with an evolving, narratively chaotic, yet also rigid aesthetic agenda, who deploy formal abstractions to explore politically and socially entangled subject matters. Consider how in Bonello’s second film, The Pornographer (2001), Jean-Pierre Léaud—star of François Truffaut’s New Wave masterpiece The 400 Blows (1959) and a symbol of the iconoclastic spirit of the 1960s—plays a former acolyte of the ’68 protest movement who began directing porn in the Sexual Revolution. But just as pornography became a profitable and capitalistic industry, Léaud and his character, though once bastions of youthful rebellion, have since faded in their vitality and lost their purpose. With The Pornographer, Bonello, a child of ’68, remarks on the movement’s withering ties to the present.

The protests of ’68 had so significantly impacted French culture that, in Bonello’s view, the youth culture of the twenty-first century fed on their earlier example. In the first half of 2006, the proposed “Equal Opportunity Act” sought to deregulate labor policies concerning job safety, fair wages, and job security, sparking a series of demonstrations in France that mirrored the ’68 protests. Certain ’06 protest slogans would evoke those from ’68, and the Place de la Sorbonne, which had been occupied by students in ’68, once again became a central clashing point between protesters and the police in ’06. The link between the two movements was undeniable, and media commentators often drew parallels between them, noting the intended association. By design, the ’06 youth protest repurposed the May ’68 revolt as a method of action, recycling established ideas and wielding history to reinforce their arguments with historical parallels. Along with the French Revolution, this chapter of the country’s history remained inextricable from the culture; revolt became a facet of France’s national identity. However, where the lines between political parties seemed more distinct in the past, Bonello observed how different sides became saturated in capitalism, even if ’06 protesters decried the free-enterprise policies that drove the proposed deregulation.

With protest so ingrained into French culture, Bonello uses Nocturama to explore the youthful tendency to romanticize political violence, which, in his film, is less rooted in specific beliefs or political viewpoints than a general adolescent desire to revolt against authority. The characters have only vague political views, targeting capitalistic sources. Bonello resists giving any clear indication about the ideology at work and aims for allegorical intent. If his characters had a slogan, it would be “Our Brand is Revolt,” emphasizing the marketing of an idea like a product, the universal language in a globalized world. His young terrorists embrace the performative aspects of protest and politics, which register as referential to France’s history, theatrical in their execution, and hollow in their specificity, like commercial slogans. It’s worth noting that Bonello originally wanted to name his film Paris Est Une Fete (A Moveable Feast, 1964) after the Ernest Hemingway memoir about the author’s growth as an artist. Written amid Paris’ disillusionment after the First World War—a woeful condition that persisted despite the country’s surge of artistic output and economic prosperity—the book considers a thriving culture plagued by melancholy over the violence in the world. Nocturama employs similar contrasts.

However, Bonello would soon change the name of his screenplay due to matters out of his control. The film’s production began in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January 2015, where two masked gunmen killed 12 people, journalists and police officers among them, in response to the magazine publishing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. After principal photography wrapped on his film, Bonello was editing when the November 2015 attacks in Paris occurred. After the latter incident, Hemingway’s book became repopularized in Paris, given its portrait of the city as a beacon of life and creativity, symbolizing a defiance against terrorism. Many French citizens purchased the book in solidarity, which caused sales to skyrocket as a gesture of political capitalism. Given the book’s new relationship with contemporary events, Bonello decided to rename his film. Turning to his record collection for inspiration, he stumbled upon the 2003 album Nocturama by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. The album title refers to a zoo enclosure that houses nocturnal animals in an artificial nighttime setting, giving visitors access to animal behavior that usually occurs after dark.

When the subversives settle in the posh department store, Bonello’s program changes from Clarke and Van Sant to Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959) or perhaps John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), with the aimless tenor of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). Another collaborator, Omar (Rabah Nait Oufella), works as a security guard in the store. He promises to shut off most of the cameras, but doesn’t, and he is supposed to restrain the other security guards, but he kills them for no particular reason. After noting the absence of Fred and Greg, the group, although a well-organized machine by day, separates into disparate subgroups by night, representing a fragmented whole that more accurately typifies their politics. Working on a meticulously crafted set with eight floors because the actual department store refused to let them shoot on location, Bonello shows the group hermetically sealed inside. The store is conveniently soundproofed and devoid of windows, keeping the outside world a mystery and their isolation secure. They need only wait until the morning. In the meantime, a restless and roaming mood emerges, resulting in some of Bonello’s most pointed contrasts.

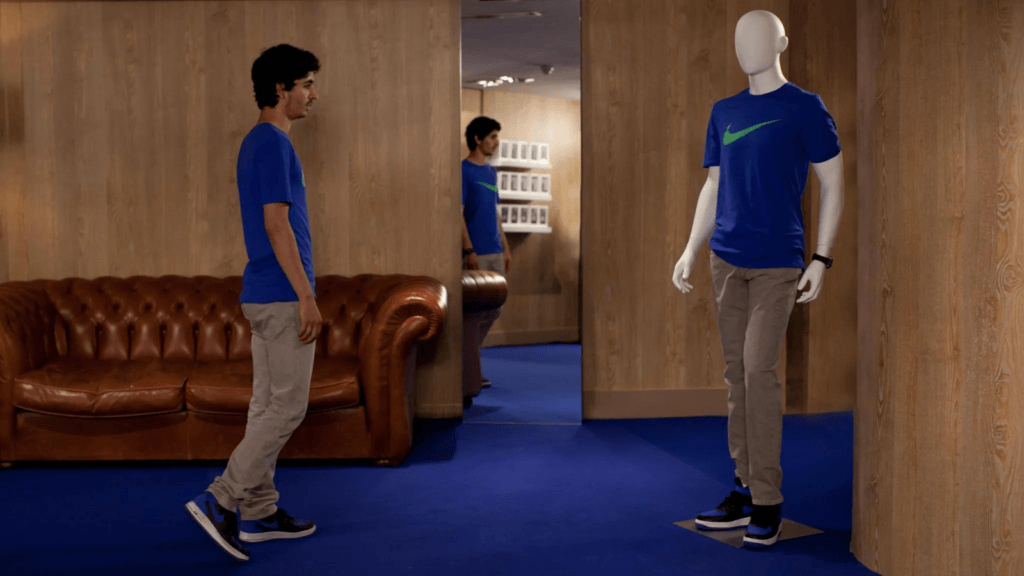

Dwindling away in a capitalist haven, the young plotters drift amid lavishly staged products and expensive merchandise as though they’re players in a twisted marketing campaign. With no action to drive them, they wander around and cannot resist taking stylish new clothes off the rack. Yacine (Hamza Meziani), dressed in a blue Nike shirt and khakis, finds his mirror image in a mannequin. Bonello cannot resist the irony and repeats it when André, dressed almost identically as a different mannequin, takes the dummy’s tie to complete his look; the mannequin now resembles how André looked just a moment ago. The bored conspirators grow restless, unable to sleep. Sarah worries that she may have killed someone, but that doesn’t prevent her from taking some make-up, a pricey brand she uses regularly, from the store. The group also raids the gourmet food and indulges in a celebratory meal. Their only company is a gray cat scurrying around the store, mostly unnoticed. And as the night goes on, members of the group feel alienated and grasp for an identity. Mika finds a mannequin storage closet, and donning a golden mask, he looks in the mirror, unsure about his reflection. Rapt with uncertainty, Mika even dreams of Greg, who confesses that, after killing the HSBC executive, he forgot to stash the gun, so he started running and eventually shot himself.

While some in the group feel disaffected and grapple with their identities in the decadent store, the day’s nihilistic events embolden David and Yacine. David suddenly feels untouchable and steps outside for a cigarette, twice. Each time, he encounters a stranger. He invites a homeless man and his wife, Jean-Claude (Luis Rego) and Patricia (Hermine Karagheuz), inside should they be hungry and want to join their “party.” David also encounters a woman with a bicycle (Adèle Haenel), who tells him that some people seem happy about the attacks; others are outraged. Either way, she observes apathetically, it was bound to happen. Yacine’s identity takes a bolder turn, with the young man preening around the store, wearing the make-up that Sabrina applied to him and Samir (Ilias Le Doré), like playing dress-up at a sleepover. A show-stopping sequence finds Yacine descending a staircase while performing a tour de force lip synch of Shirley Bassey’s “My Way,” much to the delight and confusion of his collaborators. Later, filled with hubris and bravado, he makes a vague pass at Samir by inviting him into his bath. When Samir rejects him, Yacine acts out aggressive sex with a mannequin. Yacine’s celebration seems wrapped up in performance and defiant action rather than political certainty, and Bonello shows how little ideology compels him. Like much of the group, Yacine’s confidence is only matched by his ignorance and pettiness.

Nocturama is the first in Bonello’s unofficial trilogy about the waywardness and chaos of youth, followed by Zombi Child (2019) and Coma (2022). Here, the writer-director reminds us that these perpetrators are ostensibly children, flashing back to the group’s preparation to underscore their naïveté. After their plans have been laid, on the last night before the point of no return, they have a house party with video games, aggressive rap, and alcohol. This is followed by a mindless, zombie-like dance to thumping music—complete with a hypnotic rhythm, prompting them to float around the room together, nodding to the beat before huddling like a football team. Back in the department store, this behavior continues. Omar blasts Willow Smith’s “Whip My Hair” for his fellow purist revolutionaries and can’t decide what’s better, the song or the sound quality on those Bang & Olufsen speakers. Smith wrote the song when she was 10, observes Omar, which he says is “sick”—a term that might have expressed disdain from a steadfast anti-capitalist upstart; instead, Omar means it admiringly. Against the song, Bonello and editor Fabrice Rouaud assemble a montage of the group’s destruction on a news broadcast, playing like a warped music video. Does the group embrace these capitalistic symbols sardonically? Or are they merely oblivious hypocrites?

Bonello’s intentional political ambiguity gives way to his portrait of youth as easily distracted after carrying out their strikes, which builds unexpected empathy within the viewer. Bonello allows us to see the youths not as manifestations of a political ideology but as human beings who flounder and have taken their rebellious self-discovery too far. Hints at their beliefs aside, Bonello focuses on their behavior first, not their ideas. He told Film Comment, “I was afraid the discourse [on what they were protesting] would create a distance from the action and I didn’t want that. I wanted the discourse to be within the action.” Bonello wrote the script in 2010 and, even in the aftermath of contemporary terrorism, resists perpetuating Islamophobic cinema. Instead, he has compared his characters to punk rockers or typically young Kamikaze soldiers, whose passions manifest aggressively. And though outside the schemers appear resolute in their precision planning, they waver inside, revealing their most ironical and youthful behaviors. When Blondie’s “Call Me” blares throughout the store, Sabrina dances along like Ally Sheedy rocking out in The Breakfast Club (1985). Cinematographer Léo Hinstin’s smooth camera movements track the characters outside, but they also follow Yacine on a go-cart inside the store, bringing to mind Danny navigating the Overlook Hotel’s corridors on a Big Wheel trike in The Shining (1980).

While Benello avoids constructing psychologically complex characters, he conveys their states of mind to create a kind of identification with their detached actions and passive enjoyment of the store’s luxuries. He even manages sympathy for their increasing sense of anxiety and doom as the night carries on, the authorities label them “enemies of the state,” and a police strike force assembles around a street corner. The plotters’ inexperience is almost tragic for their ignorance, as they brought leftover Semtex to the store to defend themselves but forgot the detonators. Because Bonello resists political discourse, there’s no clear oppositional relationship between the French state and the conspirators, so when the police engage the store and proceed to wipe out the youths, their deaths are brutal. The authorities kill them each on sight, whether they’re armed or not. Bonello pans over the security camera monitors, showing their deaths on a two-by-two screen setup at a chilly distance. If the plotters put themselves in this situation, the only victims are the homeless couple David invited inside, killed in the merciless strike force raid. With most of his friends dead, Samir shouts, “Help me!” with the desperation of a child who’s fallen down a well. He, too, is shot dead without hesitation. “The overall mood as the credits roll is one of waste, loss, and a confounding sense of beauty,” noted critic Darragh O’Donoghue.

While many critics praised Bonello’s film, it was the subject of mild controversy in France. Perhaps due to its representation of terrorist attacks on Paris, but more likely due to the general political sensitivities at the time, the Cannes Film Festival rejected Nocturama, even though his previous two films, House of Pleasures (2011) and Saint Laurent (2014), competed at the festival. Writing in Positif, French critic Michel Ciment suggested Bonello’s film is “irresponsible.” That view ignores the fibrous reality of Bonello’s film, his focus on the group’s action over the destruction they caused, and the political change they either intended or achieved. But their actions did not open a dialogue; they are eliminated without negotiation, interview, or interrogation. In this, Bonello delivers a readable but not unequivocal film. With myriad interpretations and misdirections, the filmmaker avoids the absolutism usually expected in response to acts of political violence. Bonello isn’t one to make pronouncements or simple declarations. His portrait of terrorism is less politically minded than a remark on privilege, ego, and reckless self-indulgence. Rather than get swept up in political fervor, he approaches the subject with critical distance and consideration, raising questions instead of reinforcing viewpoints. The director dedicated the film to his teenage daughter, perhaps to remind her that passions, politics, and even beliefs ebb and flow.

When The Beatles released their song “Revolution” the same year as the May 1968 riots in France, the Fab Four intended a potent reflection of the defiant spirit in the air. They could not have known that Michael Jackson would buy the rights to their songs in 1985 and sell “Revolution” to Nike for a shoe campaign. One sees a similar dynamic in this group of would-be revolutionaries who, the night before taking action against the state, were playing video games and acting like aimless teens. In a world overrun by capitalism that has commodified revolutions, what possible meaning could any of this have besides a temporary interruption in the flow of life, a featured story on the 24-hour news cycle, and an incident to which some will cling to justify performative trauma? Bonello’s focus on their action in Nocturama captures their familiar gestures and fruitless methods, and perhaps, in an elusive and roundabout way, suggests that political violence no longer constitutes productive political action. But Bonello offers no explicit thesis or easy solutions, investing himself in the dreamy haze of youth in all its misguided passion, to engross his audience but leave them uncertain about what it all means. That’s preferable to the irresponsible assuredness the characters adopt in his film.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on August 7, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Akler-Bishop, Ryan. “Interview: Bertrand Bonello.” Our Culture, 16 October 2023. https://ourculturemag.com/2023/10/16/interviewbertrand-bonello/. Accessed 27 July 2024.

“Interview: Bertrand Bonello – Nocturama.” YouTube, uploaded by IONCINEMA, 7 August 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQVWAG2gWNQ. Accessed 27 July 2024.

Hampton, Howard, and Violet Lucca. “Blank Generation.” Film Comment, vol. 53, no. 3, 2017, pp. 52–56.

Lucca, Violet. “Frame to Frame: Nocturama.” Film Comment, vol. 53, no. 3, 2017, pp. 52–56.

—. “Directions: Bertrand Bonello.” Film Comment, January-February 2017. https://www.filmcomment.com/article/interview-bertrand-bonello-nocturama/. Accessed 27 July 2024.

McElhaney, Joe and David A. Gerstner. “Zombi Child and the Spaces of Cinema: An Interview with Bertrand Bonello,” Cineaste, Vol. 45, No. 2, 2019.

O’Donoghue, Darragh. Cinéaste, vol. 43, no. 1, 2017, pp. 46–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26356828. Accessed 28 July 2024.

Reichert, Jeff. “Nocturama.” Reverse Shot, 21 August, 2017. https://reverseshot.org/reviews/entry/2351/nocturama. Accessed 27 July 2024.

Weston, Hillary. “Behind Closed Doors: A Conversation with Bertrand Bonello.” The Criterion Collection, 11 August 2017. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4816-behind-closed-doors-a-conversation-with-bertrand-bonello. Accessed 27 July 2024.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review