The Definitives

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead birthed not only the zombie horror phenomenon but also the subsequent decades of exploitative, ultra-low-budget pictures hell-bent on scaring audiences out of their seats. Arriving at Saturday matinées and frightening the willies out of the mostly adolescent attendees, and adult ones too, Romero’s 1968 debut film awakened viewers out of their complacency toward the horror genre. The film’s gritty, cinema verité style lends a startling realism, as well as a biting potential for social commentary, and a merciless, unconventional finale that shocked viewers. Night of the Living Dead was not another pulpy B-movie wrought with space aliens, monsters from the abyss, and atomic-era mutations. Romero’s film turned people, among them our friends and family members, into flesh-eating ghouls. And beyond the terror of its concept, the film bolstered thematic undercurrents that reflected timeless notions of civil rights and human savagery, punctuating them with a carnival of cannibalistic violence. Moviegoers had never seen anything like it before.

Horror films before the 1960s relied on atmosphere and men in makeup or rubber suits to evokes scares. Universal Studios’ monsters had frightened audiences for two decades, followed by atomic age abominations in the 1950s. However, in the latter part of the 1950s and 1960s, especially after the abandonment of the Production Code in 1964, blood and gore began to emerge as more prominent strains of onscreen horror. British company Hammer Film Productions released numerous color features detailing alternate, gory takes on classic horror icons, as seen in The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966)—both featuring Christopher Lee’s breathtaking portrayals as the respective monsters. Alfred Hitchcock broke mainstream ground by uncovering suspense-fueled psychological horror with Psycho (1960) and elevated the common Nature vs. Man theme to artistic heights with The Birds (1963). At the same time, horror films of the 1950s and 1960s took low priority for producers; certainly not prestige pictures, they were often produced with lower budgets and lesser talent, save for a few select exceptions. While the market for horror remained minuscule, it also maintained formulaic expectations wherein, following a procession of thrills, the hero delivered a happy ending.

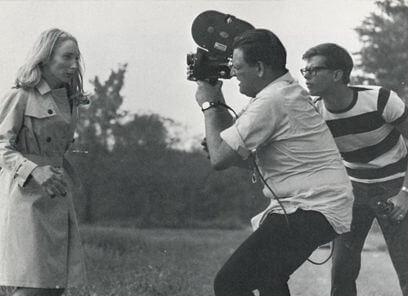

Romero changed all that with Night of the Living Dead. Born in 1984 in New York City, this son of a Cuban father and Lithuanian mother became interested in film at a young age after seeing Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s opera film Tales of Hoffmann (1951). To explore the medium, he experimented with the 8mm camera he received as a gift from his uncle, making short films with titles like “Man from the Meteor” and “Gorilla” before finally going off to college. At Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Romero earned his bachelor’s degree in theater and design in 1960. After shooting several shorts and commercials for a company he formed alongside friends John Russo and Russell Streiner, he resolved to form a feature film production company, called Image Ten, with nine other founders. Their first effort intended to exploit the public’s thirst for the scary while acknowledging that most titles in the horror genre could be made cheaper, and therefore earn a faster profit.

Romero changed all that with Night of the Living Dead. Born in 1984 in New York City, this son of a Cuban father and Lithuanian mother became interested in film at a young age after seeing Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s opera film Tales of Hoffmann (1951). To explore the medium, he experimented with the 8mm camera he received as a gift from his uncle, making short films with titles like “Man from the Meteor” and “Gorilla” before finally going off to college. At Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Romero earned his bachelor’s degree in theater and design in 1960. After shooting several shorts and commercials for a company he formed alongside friends John Russo and Russell Streiner, he resolved to form a feature film production company, called Image Ten, with nine other founders. Their first effort intended to exploit the public’s thirst for the scary while acknowledging that most titles in the horror genre could be made cheaper, and therefore earn a faster profit.

Romero and Russo collaborated on several screenplay drafts. Their first draft, titled “Monster Flick,” centered on teenaged aliens befriending human adolescents. The story evolved over several drafts into a tale of flesh-eating corpses. The title changed from “Night of Anubis” (named after the Egyptian embalming and flesh-eating god) to “Night of the Flesh Eaters,” while the script called the living dead “ghouls” and never mentioned the word “zombie” within its pages. Romero was careful to avoid direct references to Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend, which first popularized the notion of flesh-eating hordes in a post-apocalyptic setting. Despite the similarities to Matheson’s text, Romero and Russo’s concept was deceptively simple: Recently dead bodies reanimate and stagger about with outstretched arms, ravenous for human flesh. They tear into you, rip your innards out from your belly, and as they eat you, you face the grim realization surfaces that within a short period you too will hunger and feed. Survivors take refuge in a farmhouse, board the windows and doors, and attempt to understand the situation. Outside, pale grotesque figures with torn flesh and drooping postures slowly reel closer, banging on the structure, gathering in numbers.

Within the first moments of Night of the Living Dead, the film distinguishes itself from the romantic horror established by major studios. “They’re coming to get you, Barbra,” teases Johnny (Russell Streiner), who uses a vampire voice that acknowledges the cartoonish Hollywood monster movies of yesteryear. Johnny’s sister, Barbra (Judith O’Dea), feels jumpy about cemeteries; undoubtedly, she associates them with spooky, fog-machined places where spiders crawl and rubber bats flap in the moonlight. Such filmic archetypes come crashing down in favor of Romero’s far more realistically presented vision shot during the day. A man stumbles toward the siblings in the background of this scene. Johnny continues to tease Barbra about the man coming to get her, until the man, a reanimated corpse, leaps at Johnny and kills him. Terrified, Barbra runs for her life. She tries to escape in their car, but in a panic, she crashes it. She tries to get away on foot. Other slow-moving ghouls pepper the countryside. Barbra finally finds safety at a nearby farmhouse. With this self-aware sequence, the old, hokey days of cinematic horror become frighteningly real.

Within the first moments of Night of the Living Dead, the film distinguishes itself from the romantic horror established by major studios. “They’re coming to get you, Barbra,” teases Johnny (Russell Streiner), who uses a vampire voice that acknowledges the cartoonish Hollywood monster movies of yesteryear. Johnny’s sister, Barbra (Judith O’Dea), feels jumpy about cemeteries; undoubtedly, she associates them with spooky, fog-machined places where spiders crawl and rubber bats flap in the moonlight. Such filmic archetypes come crashing down in favor of Romero’s far more realistically presented vision shot during the day. A man stumbles toward the siblings in the background of this scene. Johnny continues to tease Barbra about the man coming to get her, until the man, a reanimated corpse, leaps at Johnny and kills him. Terrified, Barbra runs for her life. She tries to escape in their car, but in a panic, she crashes it. She tries to get away on foot. Other slow-moving ghouls pepper the countryside. Barbra finally finds safety at a nearby farmhouse. With this self-aware sequence, the old, hokey days of cinematic horror become frighteningly real.

Joining Barbra, Ben (Duane Jones), an African-American man, approaches the farmhouse in a pickup truck running on Empty. He makes his way inside, bludgeoning the living dead with a tire iron. He finds Barbra near catatonic, so he sits her down and tries to talk out what has happened to the world. News broadcasts report the recently dead have returned to life; but for what reason, they do not know. Ben resolves to board-up the windows to turn the farmhouse into a reinforced stronghold. He soon realizes that more survivors have been hiding in the basement all along. Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), his wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman), and their sickly daughter (Kyra Schon) jealously protect their safe space downstairs, while a young couple (Keith Wayne, Judith Ridley) decide to help Ben fortify. The conflict between Ben and Cooper escalates to become almost as graphic as the one between the living and undead. As the threat of being eaten alive bangs its many hands against the farmhouse’s exterior, the petty survival instincts and displays of cowardice indoors stoop to their lowest potential, illustrating human nature at its worst.

Romero’s vision refuses an escapist gloss that would permit viewers to dismiss the events as mere entertainment. The characters’ pragmatism reaches realist extremes as they try to determine a practical solution. After they secure the farmhouse, they listen to broadcasts reporting on the widespread phenomenon. An announcer remarks, “Medical authorities in Cumberland have concluded that in all cases, the killers are eating the flesh of the people they kill… It’s difficult to imagine such a thing actually happening, but these are the reports we have been receiving and passing on to you, reports which have been verified as completely as is possible in this confused situation.” We can only watch the film’s characters suffer their impossible situation, feeling as helpless as they are. Romero hoped to provoke his audience, to remove them from their safe position as a viewer and involve them in claustrophobic, wholly unexplained and perilous event from all angles, unlike most then-modern horror movies rooted in mythology and fantasy. Indeed, Night of the Living Dead ends with everyone dead. The next morning outside the farmhouse, a band of ugly militia goons shoots and burns ghoul corpses. Having survived the evening, Ben emerges from the basement, the lone survivor. But the militia sees movement inside the farmhouse and opens fire, killing Ben. Romero’s audience is left unsafe, vulnerable, and utterly disturbed.

Romero’s vision refuses an escapist gloss that would permit viewers to dismiss the events as mere entertainment. The characters’ pragmatism reaches realist extremes as they try to determine a practical solution. After they secure the farmhouse, they listen to broadcasts reporting on the widespread phenomenon. An announcer remarks, “Medical authorities in Cumberland have concluded that in all cases, the killers are eating the flesh of the people they kill… It’s difficult to imagine such a thing actually happening, but these are the reports we have been receiving and passing on to you, reports which have been verified as completely as is possible in this confused situation.” We can only watch the film’s characters suffer their impossible situation, feeling as helpless as they are. Romero hoped to provoke his audience, to remove them from their safe position as a viewer and involve them in claustrophobic, wholly unexplained and perilous event from all angles, unlike most then-modern horror movies rooted in mythology and fantasy. Indeed, Night of the Living Dead ends with everyone dead. The next morning outside the farmhouse, a band of ugly militia goons shoots and burns ghoul corpses. Having survived the evening, Ben emerges from the basement, the lone survivor. But the militia sees movement inside the farmhouse and opens fire, killing Ben. Romero’s audience is left unsafe, vulnerable, and utterly disturbed.

Much of Romero’s artistry developed out of necessity from shooting on a shoestring budget. Though color photography was the standard and preferred method in the 1960s, the director, who also served as cinematographer, used grainy 35mm black-and-white film stock to save on costs. Moreover, cheaper special effects could be hidden by the mask of monochrome filmmaking, such as the use of Bosco Chocolate Syrup for blood or shaped mortician’s wax to create zombie wounds. Volunteer actors hoping to play zombies seemed just to arrive on set from surrounding locations near Evans City, Pennsylvania, just north of Pittsburg where filming took place. Off-putting, cockeyed camera angles and chiaroscuro use of lighting gave the result a haphazard atmosphere, as if a documentary film crew followed the unfolding horror. Further adding to the chaotic procession of captured events, Romero’s forced minimalism facilitated his blue-collar style, and therein his realism and its consequent effect on the audience. With his actors, Romero asked that they improvise their lines according to the situation, rendering their characters based on how they should feel, versus adherence to the shooting script. For instance, Jones, a well-educated man who later served as artistic director at prominent universities, refused to deliver the script’s dialogue for Ben, as the character was meant to be a dim-witted trucker. Instead, Jones’ rather erudite presence transformed the character into an instant authority figure.

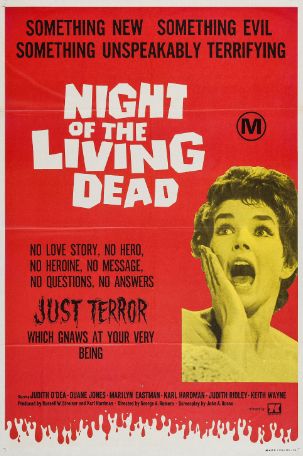

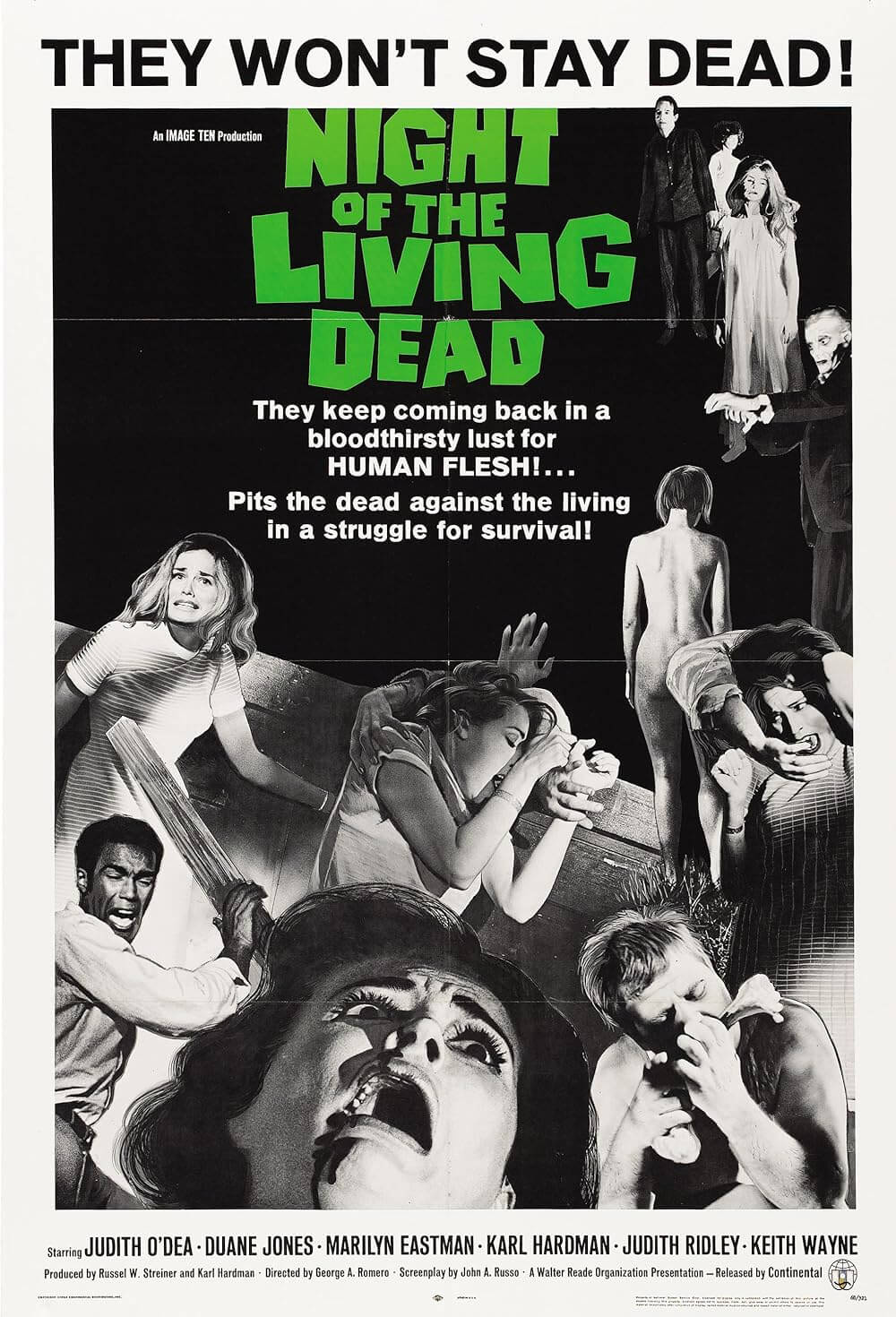

The shoot stopped and started as money allowed, lasting about six months. The small crew, comprised mostly of Image Ten’s members, facilitated the shoot and completed post-production. But getting their film distributed was another matter. Hollywood studios like Columbia and American International Pictures refused to distribute the picture without serious alterations to its graphic violence and exclamation-point ending, and so the release was independent and limited to Saturday afternoon matinées at first. However, because distributors at Continental Releasing never secured the copyright to the title Night of the Living Dead—the copyright remained under “Night of the Flesh Eaters”—the release was open to public domain. Additionally, the official release date on October 1, 1968, came a month before the Motion Picture Association of America established its new rating system. Night of the Living Dead was distributed without a prohibitory score, leaving theater owners to allow any and all ages into their screenings. But the copyright issues also meant anyone could reproduce an untraceable print and not report the box-office. Night of the Living Dead may have turned into a hit, but even decades later, after the advent of home video, only a small percentage of receipts went to the filmmakers.

The shoot stopped and started as money allowed, lasting about six months. The small crew, comprised mostly of Image Ten’s members, facilitated the shoot and completed post-production. But getting their film distributed was another matter. Hollywood studios like Columbia and American International Pictures refused to distribute the picture without serious alterations to its graphic violence and exclamation-point ending, and so the release was independent and limited to Saturday afternoon matinées at first. However, because distributors at Continental Releasing never secured the copyright to the title Night of the Living Dead—the copyright remained under “Night of the Flesh Eaters”—the release was open to public domain. Additionally, the official release date on October 1, 1968, came a month before the Motion Picture Association of America established its new rating system. Night of the Living Dead was distributed without a prohibitory score, leaving theater owners to allow any and all ages into their screenings. But the copyright issues also meant anyone could reproduce an untraceable print and not report the box-office. Night of the Living Dead may have turned into a hit, but even decades later, after the advent of home video, only a small percentage of receipts went to the filmmakers.

Within the first days of its release, Night of the Living Dead left its mark on audiences. Teenagers piled into packed moviehouses to see an unrated horror show, completely unprepared for Romero’s guerilla-style technique. Roger Ebert commented on the film’s release, “I don’t think the younger kids really knew what hit them.” Like a wildfire, the film’s popularity shifted from matinées to midnight movie showings, from children to adults, inevitably becoming a cult sensation. Most critics called it trash. Shocked, Variety took a moral stance and declared the film to be an “unrelieved orgy of sadism” purveying gore just to prove it can. They used Night of the Living Dead as a launching pad for a larger discussion about the impending MPAA censorship rules, and in turn influenced theater owners to refuse exhibitions. Few others believed it a contemporary masterpiece. Pauline Kael at The New Yorker wrote, “It would be fun to be able to dismiss this as undoubtedly the best movie ever made in Pittsburgh, but it also happens to be one of the most gruesomely terrifying movies ever made.” The polarized reactions fueled its popularity, spurring not only a successful circulation but passionate theorizing as to the film’s hidden or intended meaning.

Romero’s undeniable style echoes his control over the picture, which suggests his assured filmmaking on Night of the Living Dead was pregnant with intended commentary. Although the director claims the zombies in his debut did not serve as a specific cultural reflector, per se, he concedes that in his later films, the undead serve a planned symbolic function. Nevertheless, Romero’s zombies remain a cipher for metaphor. When decrypted, they present a symbol for society’s problems, whatever those may be. Commentators have interpreted Night of the Living Dead’s zombies as capitalists, racists, counterculturalists, and extremists, to name just a few. Other described the film’s cannibalism as humanity’s irrational compulsion for violence, our seemingly embedded need to destroy one another. Elsewhere, viewers saw the film as a reaction to anti-war protests of the current Vietnam conflict, a critique of the media, an indictment against familial and governmental establishments, and a severe blow to civil defense. Which of these readings is correct? All of them. Each argument proves valid, no matter what Romero intended, because such interpretations derive from the viewer’s experience and reading of the film.

Romero’s undeniable style echoes his control over the picture, which suggests his assured filmmaking on Night of the Living Dead was pregnant with intended commentary. Although the director claims the zombies in his debut did not serve as a specific cultural reflector, per se, he concedes that in his later films, the undead serve a planned symbolic function. Nevertheless, Romero’s zombies remain a cipher for metaphor. When decrypted, they present a symbol for society’s problems, whatever those may be. Commentators have interpreted Night of the Living Dead’s zombies as capitalists, racists, counterculturalists, and extremists, to name just a few. Other described the film’s cannibalism as humanity’s irrational compulsion for violence, our seemingly embedded need to destroy one another. Elsewhere, viewers saw the film as a reaction to anti-war protests of the current Vietnam conflict, a critique of the media, an indictment against familial and governmental establishments, and a severe blow to civil defense. Which of these readings is correct? All of them. Each argument proves valid, no matter what Romero intended, because such interpretations derive from the viewer’s experience and reading of the film.

Most common among readings of Night of the Living Dead is the film’s perceived discussion of race, largely due to the presence of Duane Jones as the protagonist. Romero insists he cast Jones as the hero simply because the actor gave the best audition. But at the same time, Romero must have been conscious that a black hero, calm and straight-headed, dealing with the hysterics of white people, would not go unnoticed in his era ripe with civil rights protests. After all, Ben slaps Barbra, the frantic blonde beauty, to calm her down; he shoots Cooper, the crazed father of a sanctimonious white family determined to hide in the fruit cellar; and he somehow remains the only survivor of the film’s tense ordeal. And in spite of his determination to survive, his reward is being shot down by a white-trash militia there to save the day. Ben’s presence, at once heroic and tragic, single-handedly revolutionizes the depiction of African Americans in cinema. Furthermore, audiences viewed his fate as a firm parallel to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and to believe Romero would conveniently overlook such significant casting gives the director insultingly low credit.

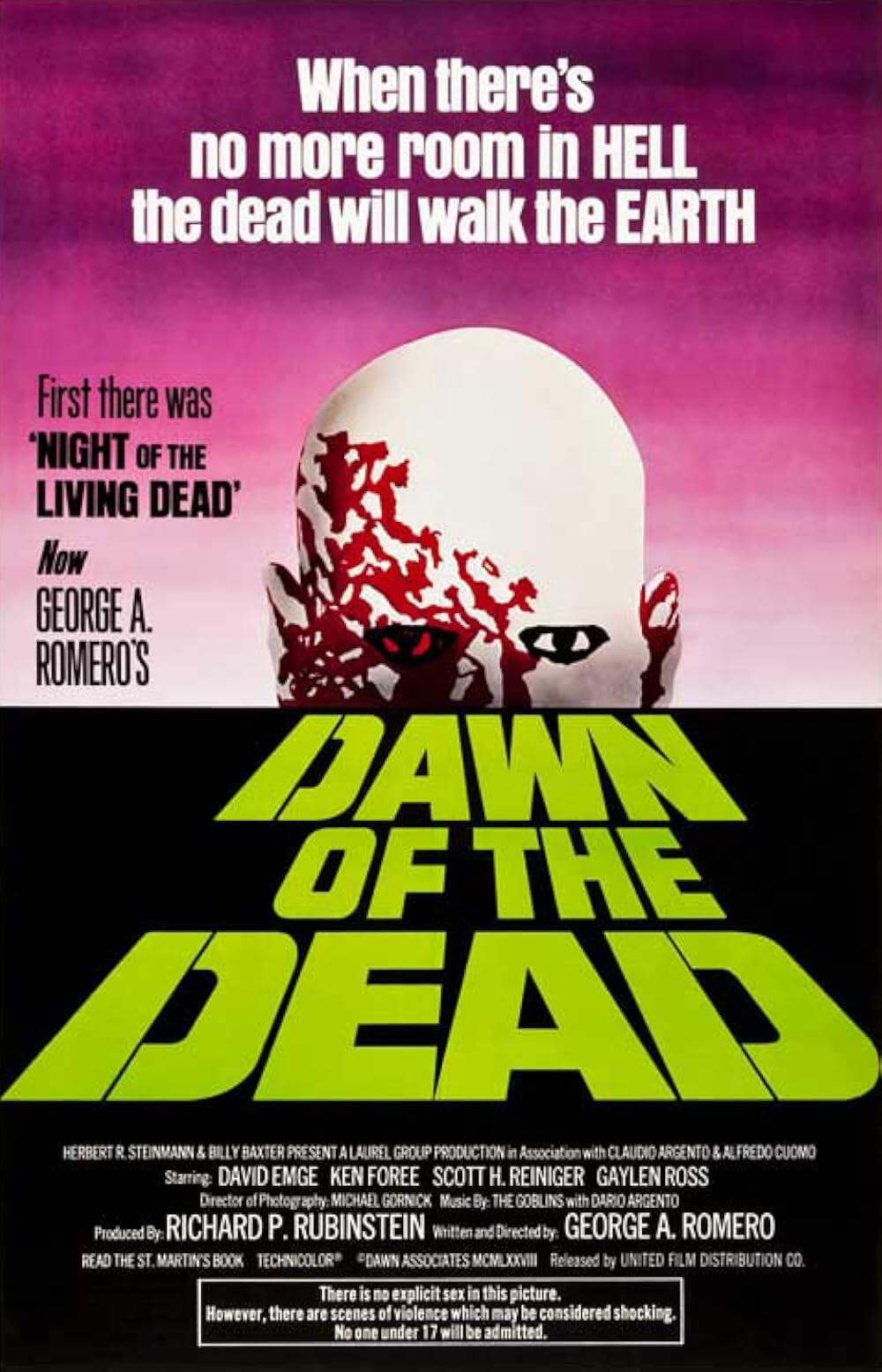

Romero’s themes and symbolism become more apparent and less ambiguous in his ensuing sequels. His focus becomes unflinchingly clear in each example, and his lucid arguments cancel out the widespread and varied interpretations that accompanied his first feature. Dawn of the Dead (1978), arguably Romero’s masterpiece, condemns modern consumerism, its zombies representing shoppers that unconsciously feed their hunger for mall surroundings. Day of the Dead (1985) strikes at the government and scientific community’s maniacal drive for control, providing a critique against those who blindly follow any such establishment. Land of the Dead (2005) satirizes the economic divide deepened by the George W. Bush Administration and condemns the social elite. Diary of the Dead (2008) addresses how our culture has become at once obsessed with and numb to video broadcasting, and seemingly incapable of seeing video as reality. Other, lesser zombie films ranging from World War Z (2013) to Zack Snyder’s 2004 remake Dawn of the Dead to those on AMC’s The Walking Dead television series set aside the social significance and implied meaning of zombies; instead, they use zombies for their cultish draw. Perhaps Romero’s unique purpose for his ghouls as prospective metaphors is why the Library of Congress included Night of the Living into the National Film Registry in 1999, or why the American Film Institute added it to their 100 Years…100 Thrills list in 2001.

Romero’s themes and symbolism become more apparent and less ambiguous in his ensuing sequels. His focus becomes unflinchingly clear in each example, and his lucid arguments cancel out the widespread and varied interpretations that accompanied his first feature. Dawn of the Dead (1978), arguably Romero’s masterpiece, condemns modern consumerism, its zombies representing shoppers that unconsciously feed their hunger for mall surroundings. Day of the Dead (1985) strikes at the government and scientific community’s maniacal drive for control, providing a critique against those who blindly follow any such establishment. Land of the Dead (2005) satirizes the economic divide deepened by the George W. Bush Administration and condemns the social elite. Diary of the Dead (2008) addresses how our culture has become at once obsessed with and numb to video broadcasting, and seemingly incapable of seeing video as reality. Other, lesser zombie films ranging from World War Z (2013) to Zack Snyder’s 2004 remake Dawn of the Dead to those on AMC’s The Walking Dead television series set aside the social significance and implied meaning of zombies; instead, they use zombies for their cultish draw. Perhaps Romero’s unique purpose for his ghouls as prospective metaphors is why the Library of Congress included Night of the Living into the National Film Registry in 1999, or why the American Film Institute added it to their 100 Years…100 Thrills list in 2001.

Everyone had a message in 1968, Romero later defended, refusing to confirm any of the dozens of hypotheses about his film’s intended meaning. Indeed, if one sets aside its vast potential for analysis, one may consider Night of the Living Dead the genius work of a provocateur whose invention constructs an open-ended allegory onto which the audience projects their subjective meanings. Structured around a figurative setting and characters vague enough to remain universal, but also active enough to be construed as something profound, Romero’s evident purpose resides in setting an abstract narrative trap for his audience, shared in its themes of revolution and human survival, so that a viewer cannot help but assign their own significance. Night of the Living Dead’s ambiguity toward its intended implication has motivated its legacy and elevated this bloody B-movie into a classic. Beyond discussions of social commentary and cultural reflectivity, the timelessness of its allegories, and the stark suggestions made by the visual presentation, Night of the Living Dead is great entertainment—the kind of late-night chiller that prompts viewers to turn on the lights when the credits roll. After forty years it still crawls under the skin and festers there, causing us to jolt and squirm better than any zombie film since. Nightmarish in both content and presentation, Romero’s debut contains the raw power that few films can muster, while remaining a subversive landmark in the horror genre.

Bibliography:

Gagne, Paul. The Zombies that Ate Pittsburgh. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1987.

Russell, Jamie. Book of the Dead. Surrey: FAB Press, 2005.

Russo, John. The Complete Night of the Living Dead Filmbook. Pittsburgh: Imagine Inc., 1985.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review