The Definitives

Network

Essay by Brian Eggert |

A battle between cinema and television has raged since the earliest monochrome broadcasts became popular in American homes during the 1950s. When the cathode ray tube first flickered images on small screens, it kept many moviegoers in their homes instead of in moviehouses. In the subsequent years, television went to great lengths to grow its audience by looking more like cinema, using increasingly cinematic and large-scale techniques to approach the formal scope of motion pictures. Ratings and audience engagement notwithstanding, not until recent years has television proved to be an artistic competitor for cinema. Early on, film retaliated in this war by producing larger screens, more grandiose images, and productions that could never be achieved on the smaller format. Film has outperformed and even satirized the lower form, confident that television represents an inferior, mass-market version of visual art as entertainment, like postcards of a Picasso. Cinema dealt its harshest blow to television in 1976, when Sidney Lumet’s film Network debuted and seemed to prophesy the next forty years of sensationalist television programming and increasingly subjective broadcast news. With startling accuracy and cultural outrage, screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky looks inside a television network and, through his biting narrative, guts the format and those involved forevermore. And while television seems to be his main target, Chayefsky’s commentary extends to all of American culture.

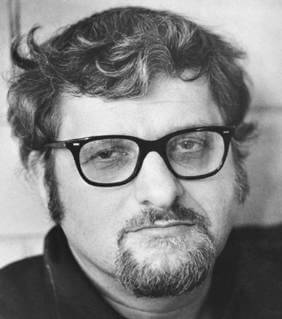

Lumet’s body of work and artistic signatures often define his projects, but Chayefsky’s unique voice had major authority over Network. Jewish and Bronx-born, the writer lived through the Great Depression and World War II. Chayefsky was unkempt and intelligent with a scruffy mop of hair, an ever-present goatee, and owlish glasses. He maintained a roguish, cantankerous personality and scathing wit, and those around him often suffered his volatile temperament. He began writing stage plays in the late 1940s, but he later found success writing teleplays for The Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse such as Holiday Song (1952) and Bachelor Party (1953), which were broadcast live from NBC’s Rockefeller Center. In this era of television, there were no established rules to the format. Chayefsky tested its boundaries with his fourth drama, Marty. The 1953 teleplay featured Rod Steiger as a thirty-year-old butcher who resolves, “Sooner or later, there comes a point in a man’s life when he gotta face some facts, and one fact I gotta face is that whatever it is that women like, I ain’t got it.” He adds, “I don’t wanna get hurt no more.” Marty’s self-aware outbursts to his friend Angie and disapproving mother portray love as an everyday experience had by everyday people, as opposed to the melodramatic event that other fiction sources had made it out to be.

Chayefsky’s characters faced the gloomy, disheartening realities and convolution of everyday life. His characters were angry and would rather die than avoid conflict; they had desires and often saw them denied by the world. Chayefsky articulated the voice of anger burgeoning within the common man. Within a few short years, Chayefsky had changed the television medium and offered its progenitors new programming possibilities, but he quickly moved on to the more profitable and esteemed medium of cinema. He adapted Marty into a script for the 1955 adaptation starring Earnest Borgnine and won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay. By this time, he had almost completely abandoned television; instead, he produced award-winning plays for Broadway and wrote film scripts such as the dramedy The Americanization of Emily (1964) and the musical-Western Paint Your Wagon (1969). He maintained an exceptional authority over his projects as writers rarely had, leading to his second Oscar win with The Hospital (1971), where George C. Scott plays an impotent and dissatisfied doctor. Despite his clout and two Academy Awards, by the mid-1970s the writer had written several failed pilots for television and several unproduced scripts. Commentators began to wonder where Chayefsky’s voice had gone.

Chayefsky’s characters faced the gloomy, disheartening realities and convolution of everyday life. His characters were angry and would rather die than avoid conflict; they had desires and often saw them denied by the world. Chayefsky articulated the voice of anger burgeoning within the common man. Within a few short years, Chayefsky had changed the television medium and offered its progenitors new programming possibilities, but he quickly moved on to the more profitable and esteemed medium of cinema. He adapted Marty into a script for the 1955 adaptation starring Earnest Borgnine and won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay. By this time, he had almost completely abandoned television; instead, he produced award-winning plays for Broadway and wrote film scripts such as the dramedy The Americanization of Emily (1964) and the musical-Western Paint Your Wagon (1969). He maintained an exceptional authority over his projects as writers rarely had, leading to his second Oscar win with The Hospital (1971), where George C. Scott plays an impotent and dissatisfied doctor. Despite his clout and two Academy Awards, by the mid-1970s the writer had written several failed pilots for television and several unproduced scripts. Commentators began to wonder where Chayefsky’s voice had gone.

During this time, Chayefsky grew increasingly frustrated with the world around him. He saw Anti-Semitism reaching into his postwar world, he saw suicide bombers blowing up planes, he saw cultural revolutions taking place around him, and he saw Arab money buying up major interests in the United States. At the center of his frustration was television, the medium that he had helped shape. More often than not, television paid no attention to the happenings that were of great concern to Chayefsky. With the power to bring together its countless viewers over the world, television had instead become a shameful commercial mechanism that served only to keep people apart and happily diverted. Its investors now had propagandistic and commercial interests that could not be bargained with or reshaped for the benefit of American culture, only for the benefit of profits. Ratings shaped programming, even the authenticity or political leanings of certain news divisions. Viewers now had their personal identities shaped by the sounds and pictures emanating from the idiot box—an invention that never tried to live up to its potential, but instead made everyone watch the same programming, and in turn force everyone to think in homogenous terms. Chayefsky was mad, and being a writer who could articulate his anger so well, he took aim at television, which seemed to represent all the hollowness and deprivation running wild in American culture.

The writer resolved to create a fictional network called Union Broadcasting System (UBS), complete with executives, producers, and talent, at the center of which was a “childless widower” named Howard Beale, a longtime news anchor from the days of Edward R. Murrow. Beale could be a sounding board for Chayefsky’s own anger—a virulent strain of rage that was so all-encompassing it could hardly be clarified into a singular idea. Moreover, Chayefsky had no solution to everything that was wrong with the world. When writing notes for his screenplay, he etched down his basic idea: “I want you people to get mad—you don’t have to organize or vote for reformers—you just have to get mad.” In other words, Chayefsky offers no way out or best approach to solve the issues with American culture; rather, he just wants people to recognize its problems and care enough to get angry about them. His ideas formed into Network, an incendiary cultural reflector that depicts television people as both grotesques and an allegory for his contemporary world. And if the film’s predictions about American culture seemed exaggerated upon its release in 1976, they seem frighteningly accurate in today’s era of reality television, the Kardashians, Fox News, Honey Boo Boo, and any number of cultural atrocities airing all day, every day, on hundreds of channels.

The writer resolved to create a fictional network called Union Broadcasting System (UBS), complete with executives, producers, and talent, at the center of which was a “childless widower” named Howard Beale, a longtime news anchor from the days of Edward R. Murrow. Beale could be a sounding board for Chayefsky’s own anger—a virulent strain of rage that was so all-encompassing it could hardly be clarified into a singular idea. Moreover, Chayefsky had no solution to everything that was wrong with the world. When writing notes for his screenplay, he etched down his basic idea: “I want you people to get mad—you don’t have to organize or vote for reformers—you just have to get mad.” In other words, Chayefsky offers no way out or best approach to solve the issues with American culture; rather, he just wants people to recognize its problems and care enough to get angry about them. His ideas formed into Network, an incendiary cultural reflector that depicts television people as both grotesques and an allegory for his contemporary world. And if the film’s predictions about American culture seemed exaggerated upon its release in 1976, they seem frighteningly accurate in today’s era of reality television, the Kardashians, Fox News, Honey Boo Boo, and any number of cultural atrocities airing all day, every day, on hundreds of channels.

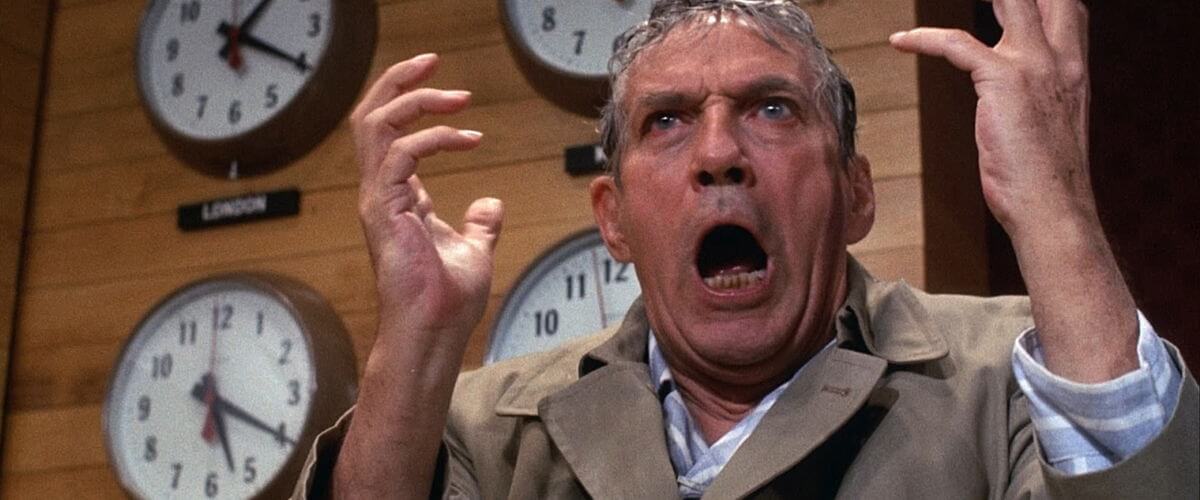

As Chayefsky’s ideas circled, he undoubtedly received further influence from twenty-nine-year-old Christine Chubbuck, a morning show anchor in Sarasota, Florida, who addressed her audience on July 15, 1974, with the following words: “In keeping with Channel 40’s policy of bringing you the latest in blood and guts in living color, you are going to see another first: an attempted suicide.” Chubbuck then pulled a .38-caliber pistol from a bag hidden beneath her desk and shot herself in the head on live television. This horrifying real-life scene would serve as an influence on the speech given by Chayefsky’s character Beale, played by Peter Finch in an Oscar-winning performance. In response to Beale’s ratings declining over the years, he’s forced into retirement by news division president Max Schumacher (William Holden). On the eve of his forced retirement, Beale addresses his audience: “I would like at this moment to announce that I will be retiring from this program in two weeks’ time, because of poor ratings. Since this show is the only thing I had going for me in my life, I’ve decided to kill myself.” The control room barely notices Beale’s announcement. He continues, “I’m going to blow my brains out right on this program a week from today.” Although Chubbuck’s name is never directly referenced within Network, the event was national news and could not have been missed by Chayefsky. In fact, the line “blow my brains out right on this program” went on to say in the first draft, “right in the middle of the seven o’clock news, like that girl in Florida.” Perhaps the line was deleted out of respect.

Stunned by Beale’s announcement, Schumacher determines the anchor is under incredible stress. And Beale starts sleeping on Schumacher’s couch. They go out for drinks, get soused, and laugh about what happened, pitching insane ideas to be featured on UBS like “Suicide of the Week” and “Terrorist of the Week”. These drunk ideas from seemingly rational men become the insane ideas pitched by young upstart producer Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway). When Beale is given another shot on the air, he delivers another outburst, saying, “I don’t have any bullshit left. I just ran out of it, you see… If there’s anybody out there that can look around this demented slaughterhouse of a world we live in and tell me that man is a noble creature, believe me: That man is full of bullshit.” Though the network receives “over 900 fucking phone calls complaining about the foul language,” the ratings spike because people want to see Beale’s rants. Christensen wants to put him on the air again and expects ratings to increase even more. “Even the news needs to have a little showbiz,” she explains.Schumacher tries to maintain the integrity of his division and protect his friend Beale from those who would exploit him. Alas, Schumacher loses his news division. Beale appears before cameras again at Christensen’s behest; she’s trying to wrangle a tornado. This time, Beale gives a speech that will soon become his tagline:

Stunned by Beale’s announcement, Schumacher determines the anchor is under incredible stress. And Beale starts sleeping on Schumacher’s couch. They go out for drinks, get soused, and laugh about what happened, pitching insane ideas to be featured on UBS like “Suicide of the Week” and “Terrorist of the Week”. These drunk ideas from seemingly rational men become the insane ideas pitched by young upstart producer Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway). When Beale is given another shot on the air, he delivers another outburst, saying, “I don’t have any bullshit left. I just ran out of it, you see… If there’s anybody out there that can look around this demented slaughterhouse of a world we live in and tell me that man is a noble creature, believe me: That man is full of bullshit.” Though the network receives “over 900 fucking phone calls complaining about the foul language,” the ratings spike because people want to see Beale’s rants. Christensen wants to put him on the air again and expects ratings to increase even more. “Even the news needs to have a little showbiz,” she explains.Schumacher tries to maintain the integrity of his division and protect his friend Beale from those who would exploit him. Alas, Schumacher loses his news division. Beale appears before cameras again at Christensen’s behest; she’s trying to wrangle a tornado. This time, Beale gives a speech that will soon become his tagline:

“We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller. And all we say is, ‘Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and my steel-belted radials and I won’t say anything. Just leave us alone.’ Well, I’m not gonna leave you alone. I want you to get mad! I don’t want you to protest. I don’t want you to riot. I don’t want you to write to your congressman, because I wouldn’t know what to tell you to write. I don’t know what to do about the depression and the inflation and the Russians and the crime in the street. All I know is that first you’ve got to get mad. You’ve got to say, ‘I’m a human being, goddamn it! My life has value!’ …So I want you to get up now. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs. I want you to get up right now and go to the window. Open it, and stick your head out, and yell, ‘I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!‘ …I want you to get up right now, sit up, go to your windows, open them and stick your head out and yell: ‘I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!’ Things have got to change. But first, you’ve gotta get mad! You’ve got to say, ‘I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!’ Then we’ll figure out what to do about the depression and the inflation and the oil crisis. But first get up out of your chairs, open the window, stick your head out, and yell, and say it: ‘I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!’”

Once completed, Chayefsky shopped his script around Hollywood and, despite an initial offer from Columbia Pictures, he settled on a deal with United Artists, which had distributed Marty and the film adaptation of his play The Bachelor Party. Fortunately, an acidic indictment of television and American culture fit with what was popular at the box office by 1974, the year Chayefsky sold Network for $300,000. Major blockbusters like The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974) still sold bundles of tickets. But a counter-culture form of cinema was becoming more popular all the time. This movement channeled the national frustrations over Vietnam and Nixon, yet more importantly the need to rebel against the system. Films like Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), M*A*S*H* (1970), and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) were independent productions made for cheap, but they performed extremely well and connected with audiences. Nevertheless, the studio worried about Network more than other films of its kind, specifically because of its attack on television and the “serious doubts about the property’s acceptability to U.S. networks for exhibition on television.”

Once completed, Chayefsky shopped his script around Hollywood and, despite an initial offer from Columbia Pictures, he settled on a deal with United Artists, which had distributed Marty and the film adaptation of his play The Bachelor Party. Fortunately, an acidic indictment of television and American culture fit with what was popular at the box office by 1974, the year Chayefsky sold Network for $300,000. Major blockbusters like The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974) still sold bundles of tickets. But a counter-culture form of cinema was becoming more popular all the time. This movement channeled the national frustrations over Vietnam and Nixon, yet more importantly the need to rebel against the system. Films like Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), M*A*S*H* (1970), and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) were independent productions made for cheap, but they performed extremely well and connected with audiences. Nevertheless, the studio worried about Network more than other films of its kind, specifically because of its attack on television and the “serious doubts about the property’s acceptability to U.S. networks for exhibition on television.”

Beale may serve as Chayefsky’s onscreen voice, but he’s not the main character of Network. Dunaway is top-billed. Christensen, backed by her boss Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall), launches The Howard Beale Show—the anchor’s own soothsayer hour featuring “an angry prophet demonizing the hypocrisies of our times”. Audiences watch to see what he’ll say next, and they blindly chant his catchphrase (“I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore”). UBS’ conglomerate owner, the Communications Corporation of America (CCA), is pleased regardless of the controversy, because the news division begins to finally turn a profit. Christensen has more ideas for sensational programming, too. Consider the weekly series that follows a terrorist group called the Ecumenical Liberation Army, which kidnapped a celebrity-turned-willing-participant (not unlike the Symbionese Liberation Army’s kidnapping and allegedly brainwashing of Patty Hearst). Meanwhile, Chayefsky investigates a deranged kind of love story between Holden and Dunaway’s characters. It all comes crashing down when Beale exposes, on live television, how foreign investors now own CCA and will shape corporate interests and network programming to suit their needs. He beckons his audience to write the President of the United States, demanding he stop the takeover. “We’re a whorehouse network,” says Hackett. But that admission doesn’t stop him and Christensen from executing Beale’s on-air assassination.

As development began, Chayefsky clashed with the studio over his preferred choice of director: Sidney Lumet. Once a pioneer of great early television productions, Lumet had since moved on to cinema and earned renown for titles like 12 Angry Men (1957), Serpico (1973), and Dog Day Afternoon (1974). He was not known for counter-culture filmmaking, however; nor had he yet demonstrated the delicate balance required for black comedy or satire. The studio’s initial rejection of Lumet angered the writer. This, in addition to several displeasing meetings with United Artists’ brass about their anxiety over the content of his script, left Chayefsky wanting the deal suspended. He contacted MGM for an alternative offer. MGM had been in dire straights during the 1970s, with few hits in then-recent years. A controversial film like Network could get them back on track. It was not until both United Artists and MGM agreed to co-produce, and what’s more leave the material as its writer intended, that Chayefsky felt comfortable moving forward. With a budget of $4 million and negotiations with Lumet underway, the production began to contact actors for the role of Howard Beale. Paul Newman and George C. Scott were Chayefsky’s initial choices, followed by Gene Hackman or Henry Fonda. Chayefsky saw Max Schumacher as Lee Marvin, but Hackman or Fonda could play Schumacher too.

As development began, Chayefsky clashed with the studio over his preferred choice of director: Sidney Lumet. Once a pioneer of great early television productions, Lumet had since moved on to cinema and earned renown for titles like 12 Angry Men (1957), Serpico (1973), and Dog Day Afternoon (1974). He was not known for counter-culture filmmaking, however; nor had he yet demonstrated the delicate balance required for black comedy or satire. The studio’s initial rejection of Lumet angered the writer. This, in addition to several displeasing meetings with United Artists’ brass about their anxiety over the content of his script, left Chayefsky wanting the deal suspended. He contacted MGM for an alternative offer. MGM had been in dire straights during the 1970s, with few hits in then-recent years. A controversial film like Network could get them back on track. It was not until both United Artists and MGM agreed to co-produce, and what’s more leave the material as its writer intended, that Chayefsky felt comfortable moving forward. With a budget of $4 million and negotiations with Lumet underway, the production began to contact actors for the role of Howard Beale. Paul Newman and George C. Scott were Chayefsky’s initial choices, followed by Gene Hackman or Henry Fonda. Chayefsky saw Max Schumacher as Lee Marvin, but Hackman or Fonda could play Schumacher too.

Lumet was hesitant to sign on due to his foreseeable lack of autonomy on the production, as Chayefsky would undoubtedly defend, with a vengeance, his view of how the picture should be. To be sure, Network is not a director’s picture; it’s about the performances and writing. In a September 1975 press release announcing Faye Dunaway would star, the release called the film “Paddy Chayefky’s Network” and did not mention Lumet until the second paragraph. The release also mentioned William Holden was close to signing, which he did, leaving only the pivotal role of Howard Beale left to cast. Chayefsky’s first choice, Paul Newman, turned down the part in favor of Robert Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976). An unexpected choice came in Peter Finch, who had earned an Oscar nomination in 1972 for John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday. But Finch’s reputation for hard-drinking with fellow cohorts Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris, and Errol Flynn, as well as his British and Australian upbringing, worried Network‘s producers. They made Finch audition for the role of Beale to demonstrate his American accent. Before they even sat down after the actor left the reading, producer Howard Gottfried, Chayefsky, and Lumet knew they had their man.

Filming began in January of 1976, and while the production offered few major technical challenges, its actors were confronted with several long speeches written in Chayefsky’s brilliant dialogue. Ned Beatty plays network head Arthur Jensen, who gives a three-minute speech to Beale for having “meddled with the primal forces of nature” in a booming, from-the-top-of-the-mountain voice. Jensen rebuts Beale’s ideas about a corrupt America and declares there is “no America, no democracy, only IBM and ITT and AT&T and Dupont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon.” Finally Beale asks Jensen, “Why me?” Jensen responds, “Because, you’re on television, dummy.” Chayefsky remained on-set throughout shooting, giving his feedback on each scene (“It’s okay,” the writer told Beatty of his performance in the iconic scene.) As a flu strain made its way through the cast and crew, the usual filmmaking problems arose. Holden had long expressed his misgivings about filming love scenes and, only ten days into production, Dunaway protested showing her bare breasts in a love scene between Diane and Max, though she had done so previously in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Chinatown (1974). Lumet shot the famous scene where Diane achieves orgasm while discussing ratings and Dunaway kept her clothes on.

Filming began in January of 1976, and while the production offered few major technical challenges, its actors were confronted with several long speeches written in Chayefsky’s brilliant dialogue. Ned Beatty plays network head Arthur Jensen, who gives a three-minute speech to Beale for having “meddled with the primal forces of nature” in a booming, from-the-top-of-the-mountain voice. Jensen rebuts Beale’s ideas about a corrupt America and declares there is “no America, no democracy, only IBM and ITT and AT&T and Dupont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon.” Finally Beale asks Jensen, “Why me?” Jensen responds, “Because, you’re on television, dummy.” Chayefsky remained on-set throughout shooting, giving his feedback on each scene (“It’s okay,” the writer told Beatty of his performance in the iconic scene.) As a flu strain made its way through the cast and crew, the usual filmmaking problems arose. Holden had long expressed his misgivings about filming love scenes and, only ten days into production, Dunaway protested showing her bare breasts in a love scene between Diane and Max, though she had done so previously in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Chinatown (1974). Lumet shot the famous scene where Diane achieves orgasm while discussing ratings and Dunaway kept her clothes on.

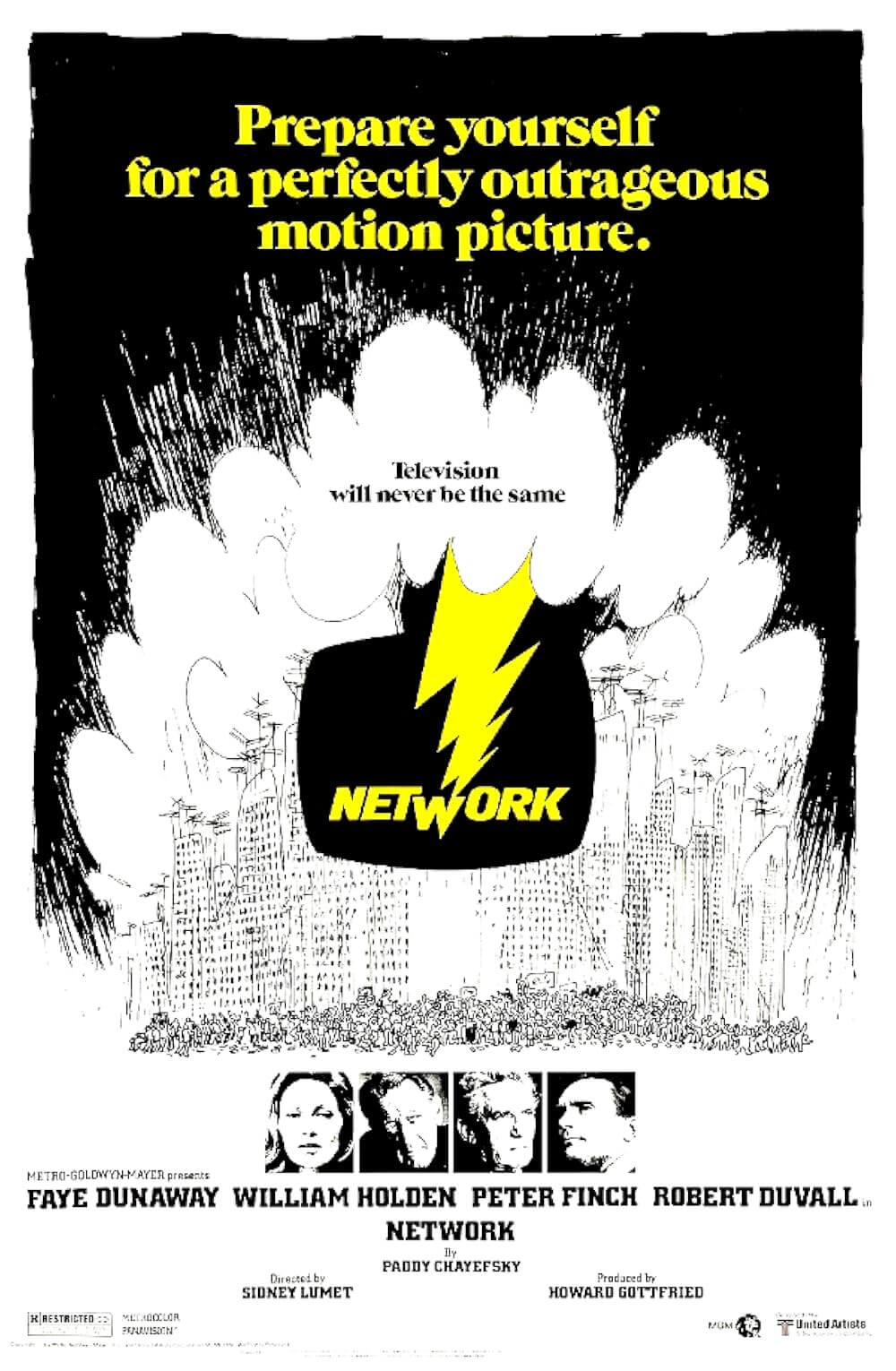

On March 25, filming wrapped after shooting some of the most memorable moments of Network, when suggestible television viewers run to their windows at Beale’s insistence and shout their lungs out, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” Before the film was released and its promotion was fully underway (the poster declared, “Television will never be the same again” under storm clouds bursting with lightning), Chayefsky remarked “I know I am in for a storm of humanity.” MGM and United artists spend almost as much on the marketing campaign as the film itself, including prescreenings for important figures whose accolades would generate anticipation for the November 27, 1976 release. Amid the praise, television personalities shot back. NBC producer Paul Friedman said, “It would be a shame if it were a big hit,” because Friedman felt, “It’s simply not true. Television is not as powerful as Paddy Cheyefsky thinks it is.” CBS’ Walter Cronkite attempted to make it a non-issue, saying, “I really don’t find any great significance in it.” Just knowing what it was about, many television critics refused to see the picture. Chayefsky responded with an open letter that states, “Television people should stop worrying about whether their image is being tarnished and start examining their responsibilities to the public.”

Film critics were far more favorable to Network, perhaps because their opinion of television had better reason to align with Chayefsky’s. Vincent Canby’s November 15 review in the New York Times said, “His humor is not gentle or generous. It’s about as stern and apocalyptic as it’s possible to be without alienating the very audience for which it was intended.” Many critics concurred, calling Network “outrageous” and “hilarious satire”. Overall, however, the responses were polarized, with dissenters like Pauline Kael writing in the New Yorker that Chayefsky was like “a Village crazy bellowing at you: blacks are taking over, revolutionaries are taking over, women are taking over.” New York Post critic Frank Rich called it “drastically out of control.” Critics, it seemed, were resistant in one way or another to Chayefsky’s truth, whether they disagreed with its merits or protested the darkly satiric way in which the author chose to present his argument. In other, smaller circles, Network had an unexpected effect. Chayefsky received a letter from ABC’s assistant to the president of the entertainment division praising him for the film. “P.S.,” she wrote, “I’m quitting my job.”

Film critics were far more favorable to Network, perhaps because their opinion of television had better reason to align with Chayefsky’s. Vincent Canby’s November 15 review in the New York Times said, “His humor is not gentle or generous. It’s about as stern and apocalyptic as it’s possible to be without alienating the very audience for which it was intended.” Many critics concurred, calling Network “outrageous” and “hilarious satire”. Overall, however, the responses were polarized, with dissenters like Pauline Kael writing in the New Yorker that Chayefsky was like “a Village crazy bellowing at you: blacks are taking over, revolutionaries are taking over, women are taking over.” New York Post critic Frank Rich called it “drastically out of control.” Critics, it seemed, were resistant in one way or another to Chayefsky’s truth, whether they disagreed with its merits or protested the darkly satiric way in which the author chose to present his argument. In other, smaller circles, Network had an unexpected effect. Chayefsky received a letter from ABC’s assistant to the president of the entertainment division praising him for the film. “P.S.,” she wrote, “I’m quitting my job.”

Indeed, for a rare few, Network was viewed as true and prophetic. Fahrenheit 451 author Ray Bradbury wrote a loving essay about the film, though Bradbury argued it should have ended with Beale receiving a huge funeral—that Beale should be buried in a huge tomb with “an immense sculptured rock in front,” Bradbury wrote. Three days after the burial, the rock would be rolled away to find the tomb empty, allowing the network to stage Beale’s Second Coming, which was the network’s plan all along. Lumet was all for the hilarious idea and proposed a sequel; Chayefsky refused to entertain the rather tongue-in-cheek concept. Network went on to gross $20 million in the busy market during the fall of 1976. Films released that season included Rocky, A Star is Born, the King Kong remake, and Carrie. This was also the year of All the President’s Men, Taxi Driver, and Marathon Man. The following year, Network won Academy Awards for Best Actor (Peter Finch), Best Actress (Faye Dunaway), Best Supporting Actress (Beatrice Straight), and Best Screenplay. Finch, who had come out of semi-retirement to take the part, really wanted the Oscar and participated in countless publicity interviews for the film. Sadly, he died of a heart attack just a month before the Oscar ceremony on March 28. His widow, Eletha, accepted the award on his behalf. Health Ledger is the only other performer to receive a posthumous Academy Award.

Setting aside the awards and hullabaloo around the film upon its release, when people think of the film today, doubtful they remember the anger Chayefsky shoots toward the television industry. They’re more apt to remember Finch’s iconic scene, shouting, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” But there are two very distinct streams of rage coursing through Network. First, Chayefsky’s portrait of modern television depicts TV as one system among many dependent on conformity and homogeny—not to mention its aim at the lowest common denominator—all for profit’s sake. “I basically write stories about institutions as a microcosm of human behavior,” the writer once said. Network demonstrated how television at once shaped and reflected human behavior in the worst of ways. Just as TV people could be corrupted by any number of influences to get better ratings, all of American culture could be corrupted to make a buck. Chayefsky remarked that television news is “an industry built on hysteria” and shows “democracy at its ugliest.” Chayefsky’s argument is never clearer than during Arthur Jensen’s speech to Beale. “What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state, Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do.” Beale sits, mouth agape, as if watching as god speaks from on high. “We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale,” Jensen continues. “The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable bylaws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale. It has been since man crawled out of the slime.”

Setting aside the awards and hullabaloo around the film upon its release, when people think of the film today, doubtful they remember the anger Chayefsky shoots toward the television industry. They’re more apt to remember Finch’s iconic scene, shouting, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” But there are two very distinct streams of rage coursing through Network. First, Chayefsky’s portrait of modern television depicts TV as one system among many dependent on conformity and homogeny—not to mention its aim at the lowest common denominator—all for profit’s sake. “I basically write stories about institutions as a microcosm of human behavior,” the writer once said. Network demonstrated how television at once shaped and reflected human behavior in the worst of ways. Just as TV people could be corrupted by any number of influences to get better ratings, all of American culture could be corrupted to make a buck. Chayefsky remarked that television news is “an industry built on hysteria” and shows “democracy at its ugliest.” Chayefsky’s argument is never clearer than during Arthur Jensen’s speech to Beale. “What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state, Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do.” Beale sits, mouth agape, as if watching as god speaks from on high. “We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale,” Jensen continues. “The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable bylaws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale. It has been since man crawled out of the slime.”

The second stream of rage in Network flows like lava from the ravings shouted by Beale, the Mad Prophet of the Airwaves, who seemingly articulates the fury of the masses. He repeatedly cites his anger over foreign investments in the U.S. economy, namely a $200 million investment by Arab interests in AT&T, and other systems of corruption—growing so infuriated that his body freezes in a literal fit of rage, until he collapses to the floor. But instead of inciting his audience to into an uprising, he serves as a cathartic figurehead through which the masses are quelled into controlled cheering, rather than outright rebellion or change. Save for the example of his audience writing their protests to the President (which did not stop the CCA takeover), Beale’s speeches wash over any specific targets and instead become an all-consuming outlet, if not a comprehensive pacifier for whatever cultural angers might arise in his sermons. Finch’s iconic line from Network even becomes Beale’s catchphrase within the film, which his audience chants with enthusiasm when he appears onstage. One cannot help but wonder what Chayefsky thought when MGM and United Artists’ promotional department put the line on bumper stickers. This, and other oversimplifications of Network‘s outrage, blasted through popular culture. And while Chayefsky wanted people to get mad, the hidden genius of Network is that he shows us how the corporations will use our rage against us.

But it is not only a voice of rage that Chayefsky articulates; he also shows us how television operates like a freak show or car accident, where the weirder it is, the better. In the film, the viewers who tuned-in to see Howard Beale swear about “bullshit” eventually tune out. The novelty of Howard Beale wears off, inciting Diane to suggest Beale get “apocalyptic”. She even proposes hiring a psychic to predict the news. After all, audiences love the unexpected and unconventional. Of course, television is a business, as Chayefsky demonstrates again and again in Network. One of the best scenes involves UBS producers in contract negotiations to film Christensen’s guerilla terrorist show that follows the Ecumenical Liberation Army. The scene is hilariously ironic. As the army’s leader, the Great Ahmed, reads over his thick television contract, he munches down some Kentucky Fried Chicken. What a rebel. Meanwhile, the Great Ahmed’s top footsoldier argues, “Don’t fuck with my distribution costs! I’m making a lousy two-fifteen per segment and I’m already deficiting twenty-five grand a week with Metro! I’m paying William Morris ten percent off the top, and I’m giving this turkey ten thou per segment… The Communist Party’s not gonna see a nickel of this goddamn show until we go into syndication!”

But it is not only a voice of rage that Chayefsky articulates; he also shows us how television operates like a freak show or car accident, where the weirder it is, the better. In the film, the viewers who tuned-in to see Howard Beale swear about “bullshit” eventually tune out. The novelty of Howard Beale wears off, inciting Diane to suggest Beale get “apocalyptic”. She even proposes hiring a psychic to predict the news. After all, audiences love the unexpected and unconventional. Of course, television is a business, as Chayefsky demonstrates again and again in Network. One of the best scenes involves UBS producers in contract negotiations to film Christensen’s guerilla terrorist show that follows the Ecumenical Liberation Army. The scene is hilariously ironic. As the army’s leader, the Great Ahmed, reads over his thick television contract, he munches down some Kentucky Fried Chicken. What a rebel. Meanwhile, the Great Ahmed’s top footsoldier argues, “Don’t fuck with my distribution costs! I’m making a lousy two-fifteen per segment and I’m already deficiting twenty-five grand a week with Metro! I’m paying William Morris ten percent off the top, and I’m giving this turkey ten thou per segment… The Communist Party’s not gonna see a nickel of this goddamn show until we go into syndication!”

A scene like this may seem exaggerated and satirical, but as author and intellectual Gore Vidal once said, “I’ve heard every line from that film in real life.” Consider the real-life televised political debates between Vidal and the conservative commentator William F. Buckley, Jr. in the late sixties to early seventies. In a series of intense, unscripted deliberations, the two wits sparred and insulted each other with their highest level of intellect. This spectacle of unorthodox television where people lose their tempers and run amok on the airwaves drew audiences. The trend has only exacerbated in subsequent years. When producers realized how well this gimmick attracted viewers, more programs staged increasingly elaborate and absurd arguments, and of course losses of temper. The draw of these talk shows and provocative news interviews resulted in sensationalists like Phil Donahue, Geraldo Rivera, Jerry Springer, and other such spectacles. Today, staging real-life drama sells. Reality television seems to revolve around putting oddities on display, the stranger the better. Before the 1950s, people had carnival freak shows. Now they have television.

In a 1981 interview, Chayefsky said that “Network wasn’t even a satire. I wrote a realistic drama. The industry satirizes itself… What’s the difference? It’s all going to happen.” News broadcasters working after the film’s release see Network less as a black comedy than a statement of fact. “I have seen everything in that movie come true,” said Keith Olbermann, former anchor on ESPN and MSNBC. “Or it’s happened to me.” In the film, Schumacher argues that no independent news division has ever been responsible for its budget, but CCA wants the UBS news division to eliminate its deficit. To be sure, for decades news had been seen as a public service. But in the 1980s, networks such as CBS began laying off hundred of employees in their news division to save costs. This was another prophetic stoke on Chayefky’s part. But as conglomerates absorbed the news divisions of several networks in the ’80s, there was little protest from the television journalists involved. Don Hewitt, creator of 60 Minutes, pointed out: “We want it both ways. We want the companies we work for to put back the wall the pioneers erected to separate news from entertainment, but we are not above climbing over the rubble each week to take an entertainment-size paycheck for broadcasting news.” To maintain ratings and sustain profitability, the news media has become more sensational, more infotainment-based, and more niche-centric. Cable news networks such as Fox News and its commentator Bill O’Reilly, or the Ora network’s Off the Grid starring Libertarian Jesse Ventura, apply to a particular segment of the audience, articulating their particular brand of rage. Network would go on to inspire personalities like Stephen Colbert’s character on The Colbert Report, who behaved like one of Chayefsky’s creations. Out of character, Colbert noted the film best prefigured the trend of anchors saying, “‘I will tell you what I think and how to fell.'” He went on to say, “But even what is left of straight news, that a long time ago became how to dramatize the situation.”

In a 1981 interview, Chayefsky said that “Network wasn’t even a satire. I wrote a realistic drama. The industry satirizes itself… What’s the difference? It’s all going to happen.” News broadcasters working after the film’s release see Network less as a black comedy than a statement of fact. “I have seen everything in that movie come true,” said Keith Olbermann, former anchor on ESPN and MSNBC. “Or it’s happened to me.” In the film, Schumacher argues that no independent news division has ever been responsible for its budget, but CCA wants the UBS news division to eliminate its deficit. To be sure, for decades news had been seen as a public service. But in the 1980s, networks such as CBS began laying off hundred of employees in their news division to save costs. This was another prophetic stoke on Chayefky’s part. But as conglomerates absorbed the news divisions of several networks in the ’80s, there was little protest from the television journalists involved. Don Hewitt, creator of 60 Minutes, pointed out: “We want it both ways. We want the companies we work for to put back the wall the pioneers erected to separate news from entertainment, but we are not above climbing over the rubble each week to take an entertainment-size paycheck for broadcasting news.” To maintain ratings and sustain profitability, the news media has become more sensational, more infotainment-based, and more niche-centric. Cable news networks such as Fox News and its commentator Bill O’Reilly, or the Ora network’s Off the Grid starring Libertarian Jesse Ventura, apply to a particular segment of the audience, articulating their particular brand of rage. Network would go on to inspire personalities like Stephen Colbert’s character on The Colbert Report, who behaved like one of Chayefsky’s creations. Out of character, Colbert noted the film best prefigured the trend of anchors saying, “‘I will tell you what I think and how to fell.'” He went on to say, “But even what is left of straight news, that a long time ago became how to dramatize the situation.”

In the war between cinema and television, Network remains an atomic bomb. The West Wing writer Aaron Sorkin later remarked, “No predictor of the future—not even Orwell—has ever been as right as Chayefsky was when he wrote Network.” As Chayefky predicted, the line between news and entertainment has eroded into a warped structure that resembles nothing like the objectivity of early network news. Years later, films like James L. Brooks’ Broadcast News (1987), Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1994), Spike Lee’s Bamboozed (2001), and Sorkin’s HBO series The Newsroom (2012-2014) would critique sensationalist television, but the public had already grown so accustomed to the methods Network predicted that these films had less of an impact. Chayefsky’s extreme sense of outrage over television depicted an exaggerated world that happened to come true. What Network accomplishes is something radical, so radical that even Hollywood wasn’t aware of how prophetic the film would eventually become. Had today’s interests known how accurate the film would be in time, doubtful it would have been made. Instead, it took less than a decade for Network to look not so much like a satire than a document of horrifying truth. And it seems to get truer with every breach of journalistic integrity made by contemporary network news broadcasters. In another way, Chayefsky admits his act of protest in Network is a meaningless gesture. He acknowledges as much when Beale’s mad protests, which may have articulated a lifelong anger, eventually became part of the sideshow. One of Beale’s best lines comes to mind: “Television is not the truth, television is a goddamned amusement park.” To take Chayefsky’s argument to its final destination, he suggests that if America was in part founded on the notion that the press should act as a policer of the government, and if that policer has since been bought out in the interest of corporate profit margins, then America no longer functions as originally intended, and instead has become, as Jensen notes, “A business.”

Bibliography:

Itzkoff, Dave. Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies. New York: Times Brooks, 2014.

Lumet, Sidney. Making Movies. Vintage, 1996.

Rapf, Joanna E. (Edited by). Sidney Lumet: Interviews (Conversations With Filmmakers Series). University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review