The Definitives

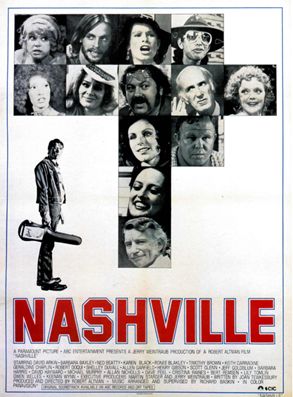

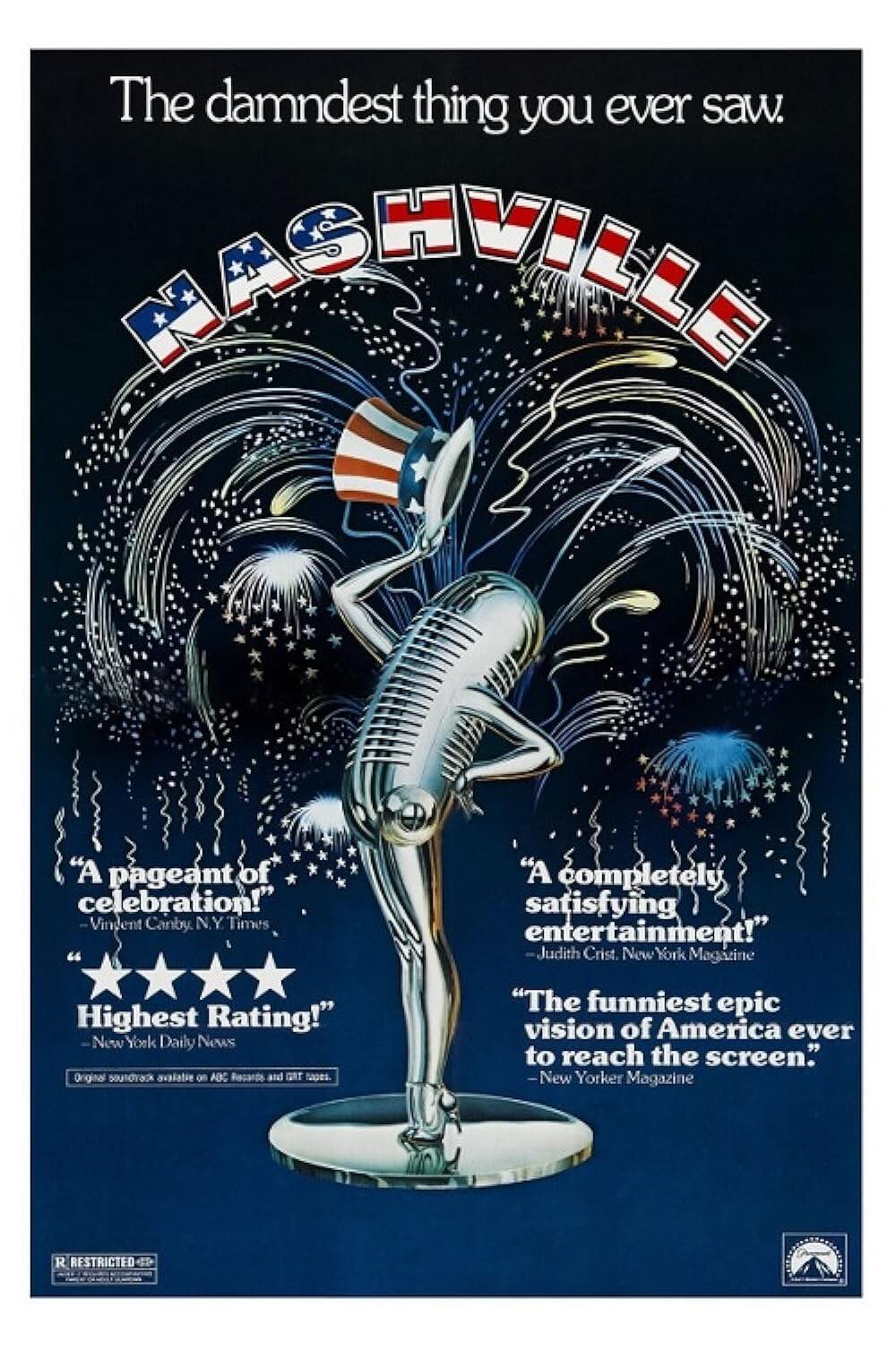

Nashville (1975)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Nashville, Robert Altman takes pieces of country music tesserae and assembles a sprawling mosaic that, grouted by the history and music of the Tennessee capital, reflects and anticipates the present and future of American culture. From our culture’s obsession with celebrity to our political candidates’ preposterous campaigns, from subjective journalism to artistic delusion, to the way all of these odds and ends intermingle, Altman’s 1975 film remains an incomparable, beautiful medley. Twenty-four main characters comprised of musicians, celebrity singers, would-be talents, weirdoes, and hand-shakers occupy the screen in and around Nashville’s country music scene, attending impressive concerts at the Grand Ole Opry and less polished performances at smoky clubs. In his then-experimental, impressionistic style, Altman captures his characters in the frame with a hint of satire, though largely without judgment, embracing their individuality within the more expansive panorama, no matter how oblique or on the margins they may seem. And yet, his film’s subject concerns not country music or the eponymous Tennessee town, but the private and artificial public lives of his American characters; through them, Altman creates a portrait that details the intricacy and incongruity of America itself.

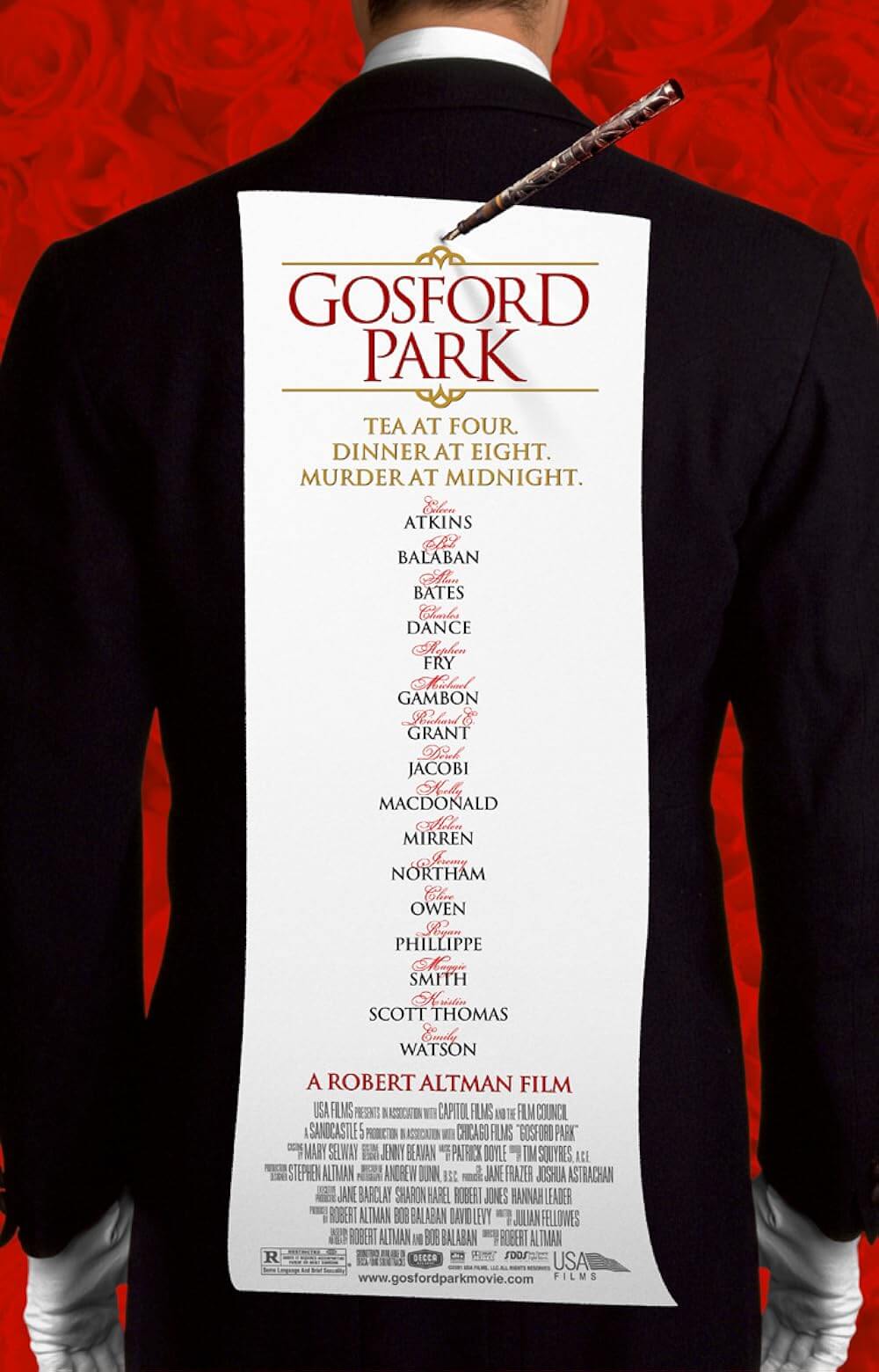

Nashville would mark the beginning of the term “Altmanesque”—revealing the term’s qualities in his later works, as well as further informing his earlier output. Altman’s technique here—subsequently explored in Short Cuts (1993), Gosford Park (2001), and A Prairie Home Companion (2006), among others—stands at the center. The director’s signatures are found in his roving, eavesdropping camera as it explores his multicharacter ensemble; we see him in the way he shows his characters in long, unbroken master shots, and almost never in close-ups; we see him in his improvised style, how he treats the script as a mere sketch instead of a strict blueprint; we see him in the way he allows his actors to improvise; we hear him in his characters’ overlapping dialogue; we see him in his intimate portrayals of women; or the way his films often seem incredibly complicated, though they’re often just about observing how characters interact. For example, in Gosford Park, a murder mystery set in the English countryside that pays homage to Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939), Altman could not care less about the murderer. He’s more interested in studying the interplay of character types, just as Renoir was. “I learned the rules of the game from watching The Rules of the Game,” the director once said. For Altman, this meant allowing his actors to explore their characters and create their own moments onscreen; in turn, the director watched as these moments, and indeed his entire film, came together before him.

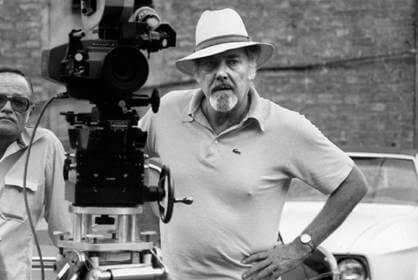

Robert Altman was born in 1925. His upper-middle-class family was well-established in Kansas City, Missouri, where he grew up sneaking into movies at the local Plaza Theater. Then, movies were “just movies” to him. After enduring Catholic schooling, Altman attended Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington and then enlisted in the air force in 1945. While flying over forty bombing missions in the Dutch East Indies, Altman also spent his military time discovering his affinity for fiction. Once he returned to the states, he used his family’s connections to begin writing script treatments, two of which were picked up by RKO. But before he ever made a film himself, Altman served for six years at Calvin Company shooting over sixty educational and operational how-to films, all the while learning the technical craft of filmmaking from writing to shooting and editing, and finally the sale of the film. After the World War II, Altman also discovered international cinema and found great influence from Bergman, Fellini, and Kurosawa, while films like David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) and John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) inspired him to look deeper into how a film could affect its audience. Most influential was the aforementioned French auteur, Renoir.

Robert Altman was born in 1925. His upper-middle-class family was well-established in Kansas City, Missouri, where he grew up sneaking into movies at the local Plaza Theater. Then, movies were “just movies” to him. After enduring Catholic schooling, Altman attended Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington and then enlisted in the air force in 1945. While flying over forty bombing missions in the Dutch East Indies, Altman also spent his military time discovering his affinity for fiction. Once he returned to the states, he used his family’s connections to begin writing script treatments, two of which were picked up by RKO. But before he ever made a film himself, Altman served for six years at Calvin Company shooting over sixty educational and operational how-to films, all the while learning the technical craft of filmmaking from writing to shooting and editing, and finally the sale of the film. After the World War II, Altman also discovered international cinema and found great influence from Bergman, Fellini, and Kurosawa, while films like David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) and John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) inspired him to look deeper into how a film could affect its audience. Most influential was the aforementioned French auteur, Renoir.

Eventually, Altman broke into television in 1954, and within three years had his first film in the can. The Delinquents from 1957, about teenage gangs, was shot using local friends and family, as well as coworkers from Calvin. United Artists distributed the film, which brought him attention. Altman’s agent showed The Delinquents to Alfred Hitchcock, who hired Altman to direct two episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. At the same time, to demystify James Dean’s burgeoning legend as a reaction to The Delinquents, Altman also made the 1957 documentary The James Dean Story. Dozens of television credits over the next decade finally led to Altman’s first studio picture, the Warner Bros. release The Countdown (1967), starring James Caan and Robert Duvall. But after seeing the dailies, which boasted Altman’s not-yet-famous overlapping dialogue, the studio took control of the picture and locked him out of the lot—believing his overlapping dialogue was due to his incompetence, rather than an intentional artistic choice. The experience forever soured Altman on studio projects. From then on out, Altman attempted to retain his independence, beginning with M*A*S*H (1970), a wartime comedy he shot under the radar at Fox. Rewriting the script and relying on instinctual, in-the-moment, and process-driven filmmaking, Altman tapped into the zeitgeist of the post-Nixon, Vietnam-era America. The film was a huge hit, which he followed with Brewster McCloud (1970), The Long Goodbye (1973), and California Split (1974).

Development on Nashville began as Altman sought to make his 1974 picture, Thieves Like Us. The director went to United Artists and pitched his idea to adapt Edward Anderson’s Prohibition-era novel, but UA wasn’t interested; they wanted Altman to direct an existing script about country-western music since they had just purchased a record label and wanted a filmic platform to help launch original music. Altman agreed on two conditions: First, he would work out an original story with screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury; second, the deal would mean he could film Thieves Like Us. UA agreed to both conditions. But Tewkesbury knew nothing of country-western music. Altman told her to visit Nashville for inspiration. She went, kept a diary of her trip, and absorbed “the mess that [I’d] been looking for,” she later said. She studied Nashville for two weeks, and her trip ultimately shaped the script, beginning with a car accident she experienced and gospel recordings she was allowed to observe; she later visited the Grand Ole Opry and its outlying clubs. Nashville was built in a circle, she noted; you see the same people throughout the day. That notion propelled her script and its many characters, which, after reading, UA rejected. Only after record producer Jerry Weintraub, who managed John Denver, told Altman that he wanted to get into films, was the production finally established. Altman received complete independence with a meager $1.9 million budget. At least no major studio would stand over his shoulder and watch his every decision.

Development on Nashville began as Altman sought to make his 1974 picture, Thieves Like Us. The director went to United Artists and pitched his idea to adapt Edward Anderson’s Prohibition-era novel, but UA wasn’t interested; they wanted Altman to direct an existing script about country-western music since they had just purchased a record label and wanted a filmic platform to help launch original music. Altman agreed on two conditions: First, he would work out an original story with screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury; second, the deal would mean he could film Thieves Like Us. UA agreed to both conditions. But Tewkesbury knew nothing of country-western music. Altman told her to visit Nashville for inspiration. She went, kept a diary of her trip, and absorbed “the mess that [I’d] been looking for,” she later said. She studied Nashville for two weeks, and her trip ultimately shaped the script, beginning with a car accident she experienced and gospel recordings she was allowed to observe; she later visited the Grand Ole Opry and its outlying clubs. Nashville was built in a circle, she noted; you see the same people throughout the day. That notion propelled her script and its many characters, which, after reading, UA rejected. Only after record producer Jerry Weintraub, who managed John Denver, told Altman that he wanted to get into films, was the production finally established. Altman received complete independence with a meager $1.9 million budget. At least no major studio would stand over his shoulder and watch his every decision.

Twenty-four characters notwithstanding, “the drama is cumulative and collective, yet the characters are never less than distinctive,” wrote critic Molly Haskell. Altman passes through scene after scene, effortlessly cutting between his characters and their most intimate moments. At the top of this character list are the reigning king and queen of country: the badly toupeed Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson), with his massive ego, diminutive stature, and white studded jacket; the queen is Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakely), recently released from an institution for a nervous breakdown. She’s managed by Barnett (Allen Garfield), her ever-shouting husband and manager. Connie White (Karen Black), a true diva, stands as Barbara Jean’s main competition. Around Nashville, the royalty attends shows at the Old Time Pickin’ Parlor, owned by Lady Pearl (Barbara Baxley), Haven Hamilton’s compatriot. On the periphery, a young soldier (Scott Glenn) watches over Barbara Jean from a distance, as does Kenny (David Hayward), a young loner from Ohio. But competing for stage time are performers like Tommy Brown (Timothy Brown), an African-American country singer; the wannabe star Albuquerque (Barbara Harris), constantly on the run from her husband; and Sueleen Gay (Gwen Wells), a waitress who wants to be a star.

More successful are the folk trio of Tom (Keith Carradine), Mary (Cristina Raines), and Mary’s husband Bill (Allan Nicholls). Tom is something of a philanderer, who beds down with random women like L.A. Joan (Shelley Duvall), a hippie in town to visit her uncle (Keenan Wynn) and dying aunt. The sole character who interacts with every other character is Geraldine Chaplin’s Opal, an aimless and naïve BBC reporter, inspired by several types Altman had met at the Cannes Film Festival—people who claim to be from this or that network, but could really be anyone. Opal wanders about, sticking her microphone in anyone’s face, and unendingly charmed by all of Nashville. After all, where else would a magician on a three-wheel motorcycle played by Jeff Goldblum feel at home? Bemused by these types is John Triplette (Michael Murphy), who tries to sign various stars to an upcoming political campaign concert for unseen Replacement Party candidate Hal Phillip Walker. Assisting Triplette is Delbert (Ned Beatty), a lawyer with connections in Nashville. Delbert’s wife, Linnea (Lily Tomlin), a gospel singer, has two deaf children. She, too, succumbs to Tom’s advances, as do Mary and Opal.

More successful are the folk trio of Tom (Keith Carradine), Mary (Cristina Raines), and Mary’s husband Bill (Allan Nicholls). Tom is something of a philanderer, who beds down with random women like L.A. Joan (Shelley Duvall), a hippie in town to visit her uncle (Keenan Wynn) and dying aunt. The sole character who interacts with every other character is Geraldine Chaplin’s Opal, an aimless and naïve BBC reporter, inspired by several types Altman had met at the Cannes Film Festival—people who claim to be from this or that network, but could really be anyone. Opal wanders about, sticking her microphone in anyone’s face, and unendingly charmed by all of Nashville. After all, where else would a magician on a three-wheel motorcycle played by Jeff Goldblum feel at home? Bemused by these types is John Triplette (Michael Murphy), who tries to sign various stars to an upcoming political campaign concert for unseen Replacement Party candidate Hal Phillip Walker. Assisting Triplette is Delbert (Ned Beatty), a lawyer with connections in Nashville. Delbert’s wife, Linnea (Lily Tomlin), a gospel singer, has two deaf children. She, too, succumbs to Tom’s advances, as do Mary and Opal.

Altman had prepared the daunting task of recording his twenty-four characters’ overlapping dialogue by trying out the untested technology on California Split, precisely for its use on this much larger project. He adopted a 24-track recording system developed by documentarian Jim Webb to record golf tournaments. Webb’s technology placed a microphone on each main actor, allowing them to move freely within the vast shooting space of the scene. Using Webb’s innovative technology, Altman shot on location over the course of seven weeks, in Nashville, of course. Cinematographer Paul Lohmann used long lenses to allow comprehensive master shots, but this also meant Lohmann and Altman could zoom in on any actor in an enormous multi-character passage. Altman orchestrated whole environments and dispersed his actors inside them. For example, every character in the film finds themselves trapped by the opening car accident and traffic jam; just as every character appears in the final political rally. Altman made certain every scene contained several of the twenty-four main characters, allowing the viewer’s eye to wander about the frame and choose this moment or that with a particular individual. The actors, meanwhile, rarely knew if the scene revolved around their character, because Altman seldom put a camera in his actors’ face. Therefore, every actor had to be “on” even in scenes populated by a crowd, because Altman’s camera, hidden in the fracas somewhere, might be watching. Shooting this way resulted in endless reels of footage. The first cut delivered by editors Dennis Hill and Sidney Levin ran around 5 hours. Eventually, Nashville was reduced to 160 minutes, which is both an epic length, yet somehow fell short given the range of material onscreen.

While filming, Altman respected Tewkesbury’s meticulous writing and structure to inform characters, but he also gave the actors the freedom to improvise upon and write their own material. For the director, actors and casting came before any awareness of what the completed film would be; making a film was about capturing behaviors, not inventing them. Shooting was done then and there, without the opportunity to storyboard or plan. He refused to tell actors how to speak their lines or behave. However, he often took passive action to shape a performance. His cast was set up in a singles home with cheap carpets and beds for the two-month shoot to create animosity toward Black’s diva Connie White; he kept the bigger celebrity of the era, Black, in limos and posh lodgings. Elsewhere, Altman intentionally refused to listen to Carradine’s concerns about disliking his character, so Carradine behaved quite uncomfortably in every scene, which in turn the viewer translates as the character’s self-hatred. Then again, his actors came up with their own flourishes as well. Blakley improvised Barbara Jean’s on-stage breakdowns. Originally, Blakley wrote herself one long breakdown to perform; however, Altman insisted the breakdown occur over three false starts of her song. Or consider the scene in the school bus junkyard; Altman had driven by that spot every day on the way to his shoot. Finally, he decided he must shoot something there and brought Chaplin along, who improvised her entire memorable monologue. To be sure, Altman considered filmmaking a truly collaborative, instinctual effort. After the day’s shooting, he even invited his cast to watch the dailies, a rarity among directors.

While filming, Altman respected Tewkesbury’s meticulous writing and structure to inform characters, but he also gave the actors the freedom to improvise upon and write their own material. For the director, actors and casting came before any awareness of what the completed film would be; making a film was about capturing behaviors, not inventing them. Shooting was done then and there, without the opportunity to storyboard or plan. He refused to tell actors how to speak their lines or behave. However, he often took passive action to shape a performance. His cast was set up in a singles home with cheap carpets and beds for the two-month shoot to create animosity toward Black’s diva Connie White; he kept the bigger celebrity of the era, Black, in limos and posh lodgings. Elsewhere, Altman intentionally refused to listen to Carradine’s concerns about disliking his character, so Carradine behaved quite uncomfortably in every scene, which in turn the viewer translates as the character’s self-hatred. Then again, his actors came up with their own flourishes as well. Blakley improvised Barbara Jean’s on-stage breakdowns. Originally, Blakley wrote herself one long breakdown to perform; however, Altman insisted the breakdown occur over three false starts of her song. Or consider the scene in the school bus junkyard; Altman had driven by that spot every day on the way to his shoot. Finally, he decided he must shoot something there and brought Chaplin along, who improvised her entire memorable monologue. To be sure, Altman considered filmmaking a truly collaborative, instinctual effort. After the day’s shooting, he even invited his cast to watch the dailies, a rarity among directors.

Altman’s affection for his ensemble extended to the music as well. He didn’t see the point in optioning real songs when his talent could provide their own; moreover, using real Nashville songs from the icons on which his characters were loosely based (Loretta Lynn, Hank Snow, Charley Pride, Tammy Wynette, etc.) would have been too literal, whereas Altman intended something far more satiric. Richard Baskin arranged and supervised all the film’s music and chose to record live to camera, as opposed to dubbing in studio tracks in post-production. Among the castmembers were several performers with novice to extensive musical backgrounds. Blakely, who had worked with Bob Dylan and released two country albums of her own in the 1970s (entitled Ronee Blakley and Welcome), wrote “Down to the River” and “Tape Deck in His Tractor”, and performed them beautifully. Carradine had been songwriting since he was 19; the final song, “It Don’t Worry Me” had been written during Carradine’s time shooting Richard Brook’s hobo actioner Emperor of the North (1973). He also wrote “I’m Easy” and the other songs he performed in the film. Karen Black wrote the three songs she performed. For Altman, the “hillbilly” music, as he called it, was sardonic, reflecting American ideals and politics of the era, specifically those songs performed by Haven Hamilton, like “Keep A’Goin'” and “For the Sake of the Children”.

Before the film’s release in the summer of 1975, reactions were already strong. Altman invited his critical supporter Pauline Kael to screen an incomplete version, from which she famously wrote a preview in The New Yorker, announcing “It’s a pure emotional high, and you don’t come down when the picture is over.” However, Altman’s clever bid to create excitement and anticipation backfired in some circles. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby objected to Kael’s preview: “If one can review a film on the basis of an approximately three-hour rough cut, why not review it on the basis of a five-hour rough cut? A ten-hour one? On the basis of a screenplay? The original material if first printed as a book?” Nevertheless, the majority of critics praised Altman’s work as high filmic art and, as suggested by Kael, said it would change the nature of all filmmaking. However grandiose a submission (which, arguably, did not come true outside of Paul Thomas Anderson and other mosaic filmmakers), the assessments led to four Academy Award nominations (for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actress for Lily Tomlin and Ronee Blakley) and one win, to Keith Carradine for Best Original Song (“I’m Easy”). Meanwhile, the people of Nashville responded with hatred. They didn’t see Altman’s metaphor and believed, quite incorrectly, that Nashville was a straightforward portrait of Nashville. And if there was truth about Nashville within the film, they refused to acknowledge it.

Before the film’s release in the summer of 1975, reactions were already strong. Altman invited his critical supporter Pauline Kael to screen an incomplete version, from which she famously wrote a preview in The New Yorker, announcing “It’s a pure emotional high, and you don’t come down when the picture is over.” However, Altman’s clever bid to create excitement and anticipation backfired in some circles. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby objected to Kael’s preview: “If one can review a film on the basis of an approximately three-hour rough cut, why not review it on the basis of a five-hour rough cut? A ten-hour one? On the basis of a screenplay? The original material if first printed as a book?” Nevertheless, the majority of critics praised Altman’s work as high filmic art and, as suggested by Kael, said it would change the nature of all filmmaking. However grandiose a submission (which, arguably, did not come true outside of Paul Thomas Anderson and other mosaic filmmakers), the assessments led to four Academy Award nominations (for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actress for Lily Tomlin and Ronee Blakley) and one win, to Keith Carradine for Best Original Song (“I’m Easy”). Meanwhile, the people of Nashville responded with hatred. They didn’t see Altman’s metaphor and believed, quite incorrectly, that Nashville was a straightforward portrait of Nashville. And if there was truth about Nashville within the film, they refused to acknowledge it.

Indeed, Altman wanted the film to be about more than country music “gossip”, as he called it. He wanted a political element running through the story, turning Nashville into a larger metaphor. Throughout the film, the viewer notices campaign efforts for Hal Phillip Walker, leader of something called the Replacement Party. Although the candidate goes unseen for the film’s duration, we see his campaign vans patrolling Nashville’s streets, blaring political rhetoric in a device not unlike the loudspeakers from M*A*S*H. To compose the campaign oratory, Altman hired Thomas Hal Phillips, an author who also wrote his brother’s unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign. Phillips wrote the Walker campaign material from his own political beliefs that lawyers should be removed from Congress and the National Anthem should be changed to something people could understand. Phillips voiced the loudspeakers and, under Altman’s order, worked independently of the shoot, appearing each day in the backdrop with campaign signs and promoters, as though it was all happening naturally and the shot just caught it by chance. Through its physical subtext within the frame, Nashville became a metaphoric, politicized world—a patriarchy comprised of top officials like Haven Hamilton, Barbara Jean, down to other their subordinate singers. To be sure, Haven Hamilton, with all his devout patriotism, a very small man in a big wig, presides as the Country King in a rigidly enforced patriarchal society in which his queen, Barbara Jean, is soon assassinated.

It’s impossible to imagine Nashville ending any other way, perhaps because the ending is so unforgettable. Upon first viewing, the moment of Barbara Jean’s assassination seems uncharacteristic for what came before it, until considering how, early on when Barbara Jean arrives at the airport, Carradine’s rocker looks at Glenn’s soldier and says, “Kill anybody this week?” Glenn’s sly presence as a red herring distracts us from the real culprit, the quiet lodger Kenny. The assassination comes further informed by Lady Pearl, who laments the Kennedy assassinations to Opal. And no matter how shocking the moment is when Kenny shoots down Barbara Jean, no matter how violently it rips the viewer out of these meandering narratives, the death of one queen leads to another taking her place. The crowds elect the new queen when Albuquerque pulls herself onstage and sings an impassioned “It Don’t Worry Me” in the frenzied moment, calming those who haven’t already fled the scene. What a shocker, though not for shock value—for the harsh realization that before Nashville, the word “assassination” had exclusively political connotations. Indeed, the Washington Post called Altman after John Lennon was shot in 1980; he claimed they asked him, “‘Don’t you feel responsible for creating that situation, since you predicted an entertainer would be assassinated rather than a politician?’” Altman replied, “Don’t you feel responsible for not heeding my warning?”

It’s impossible to imagine Nashville ending any other way, perhaps because the ending is so unforgettable. Upon first viewing, the moment of Barbara Jean’s assassination seems uncharacteristic for what came before it, until considering how, early on when Barbara Jean arrives at the airport, Carradine’s rocker looks at Glenn’s soldier and says, “Kill anybody this week?” Glenn’s sly presence as a red herring distracts us from the real culprit, the quiet lodger Kenny. The assassination comes further informed by Lady Pearl, who laments the Kennedy assassinations to Opal. And no matter how shocking the moment is when Kenny shoots down Barbara Jean, no matter how violently it rips the viewer out of these meandering narratives, the death of one queen leads to another taking her place. The crowds elect the new queen when Albuquerque pulls herself onstage and sings an impassioned “It Don’t Worry Me” in the frenzied moment, calming those who haven’t already fled the scene. What a shocker, though not for shock value—for the harsh realization that before Nashville, the word “assassination” had exclusively political connotations. Indeed, the Washington Post called Altman after John Lennon was shot in 1980; he claimed they asked him, “‘Don’t you feel responsible for creating that situation, since you predicted an entertainer would be assassinated rather than a politician?’” Altman replied, “Don’t you feel responsible for not heeding my warning?”

Nashville depicts a political microcosm of cultural self-obsession, of whores and hypocrisy, of revered celebrities and their power. American values and country music define their microcosm. Consider the opening song, “200 Years”, in which Hamilton sings the lyric, “We must be doin’ som’thin right to last 200 years!” The song and its performance speak to the ingrained sense of entitlement in Nashville, and further, America. Watch the way Nashville’s brass gravitates toward visitors from Hollywood—Elliott Gould and Julie Christie appear as themselves—as if to validate their own sense of royalty. These are the same good ol’ boys who perpetrate the unclean scene involving Sueleen Gay, who aspires to become a famous singer, but she’s duped into a striptease by Ned Beatty. Michael Murphy sits, shrinking in his chair, realizing what he’s arranged is humiliating and going too far. But the entire scene epitomizes how each character, from Haven Hamilton to Albuquerque, sells out in their need for attention, fame, or to look bigger than they are. Barbara Jean, despite her nervous breakdown and her fragile state, keeps getting back onstage, until finally, it kills her. Perhaps the best example of the pervading dynamic between entitlement and debauchery is the duet sung between Haven Hamilton and Barbara Jean, “For the Sake of the Children”—a song about two adults having an extramarital affair, who then decide to break it off “for the sake of the children”. More bittersweet and affecting is the scene where Tomlin’s character tenderly teaches Carradine’s Tom the symbol for love in sign language; but when she refuses to stay in Tom’s bed, she’s quickly dismissed. With thorough indifference, Tom calls another girlfriend with Tomlin still inside the room. Somehow, Tomlin manages to maintain her integrity as she bids him farewell when she shuts the door.

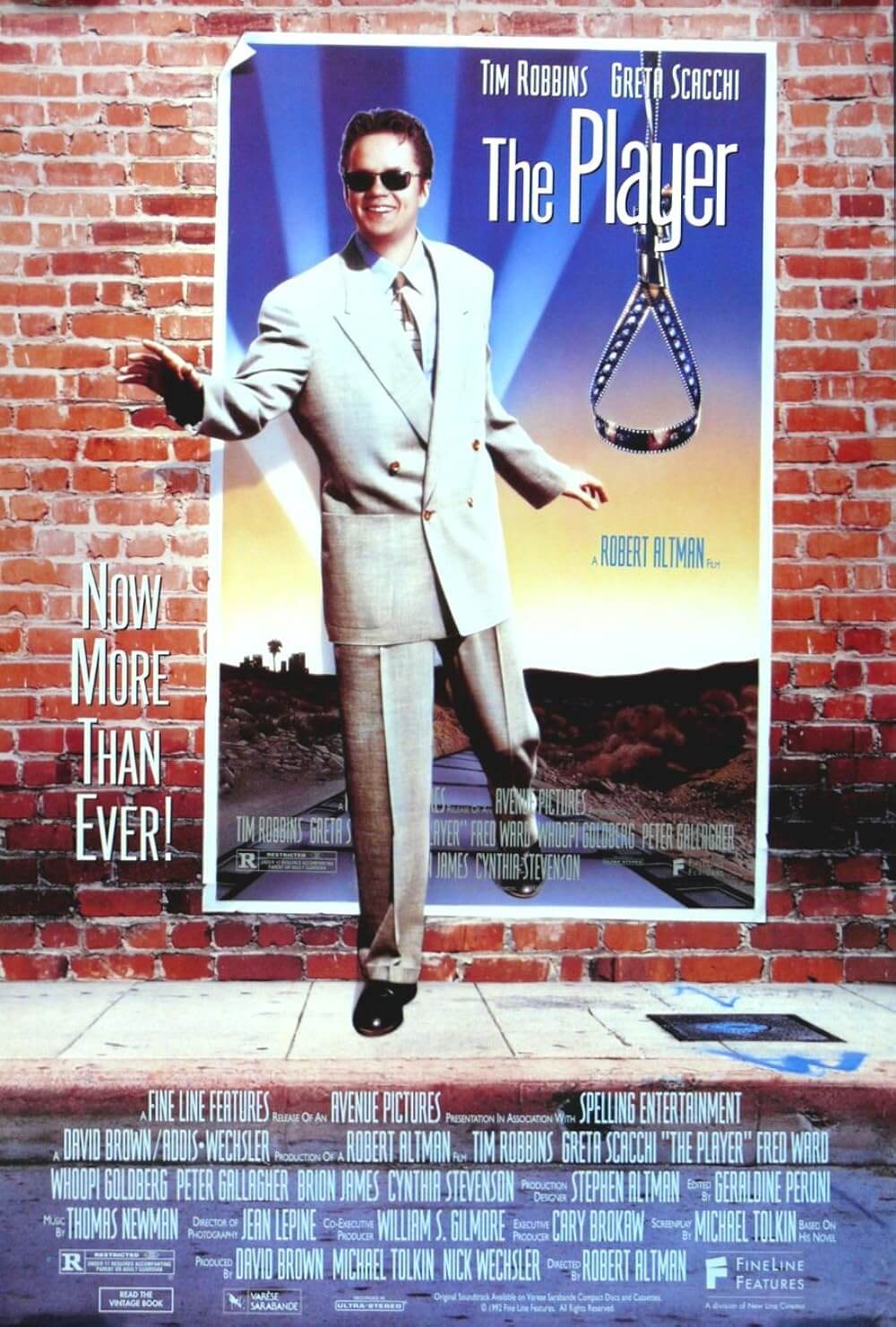

A myriad of warm, cruel, and multilayered moments exist in Nashville, insomuch that Robert Altman’s film appears to be about nothing. But it’s about everything. A million fascinating, seemingly insignificant details flood the crowds, stage performances, and intimate moments in Nashville, so that any devoted viewer must watch again and again to see more, and always there’s something new to be discovered. The film represents the first time Altman was allowed to, as he described it, “Paint a mural” on film, where the sprawling yet quaint production and many-sided stories develop through happenstance. Nashville manages to be about politics, music, American’s topsy-turvy status at the time, hierarchies in the social and entertainment ranks, and so much more. The filmmaker captures the full breadth of his cinematic ambitions for the first time in his career (which is not to suggest his earlier titles such as McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye are anything short of brilliant). But from here on out, Altman developed many of his films this way, more often than not with incredible results (Short Cuts, The Player, and Gosford Park, remain the most closely tied to Nashville). It would be the first, but certainly not the last time this filmmaker would discover for himself what it means to be Altmanesque.

A myriad of warm, cruel, and multilayered moments exist in Nashville, insomuch that Robert Altman’s film appears to be about nothing. But it’s about everything. A million fascinating, seemingly insignificant details flood the crowds, stage performances, and intimate moments in Nashville, so that any devoted viewer must watch again and again to see more, and always there’s something new to be discovered. The film represents the first time Altman was allowed to, as he described it, “Paint a mural” on film, where the sprawling yet quaint production and many-sided stories develop through happenstance. Nashville manages to be about politics, music, American’s topsy-turvy status at the time, hierarchies in the social and entertainment ranks, and so much more. The filmmaker captures the full breadth of his cinematic ambitions for the first time in his career (which is not to suggest his earlier titles such as McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye are anything short of brilliant). But from here on out, Altman developed many of his films this way, more often than not with incredible results (Short Cuts, The Player, and Gosford Park, remain the most closely tied to Nashville). It would be the first, but certainly not the last time this filmmaker would discover for himself what it means to be Altmanesque.

Bibliography:

Haskell, Molly. “Nashville: America Singing.” Criterion.com. December 02, 2013.

McGilligan, Patrick. Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1989.

Thompson, David (edited by). Altman on Altman. London: Faber and Faber, 2006.

Zuckoff, Mitchell. Robert Altman: The Oral Biography. New York: Random House, 2009.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review