The Definitives

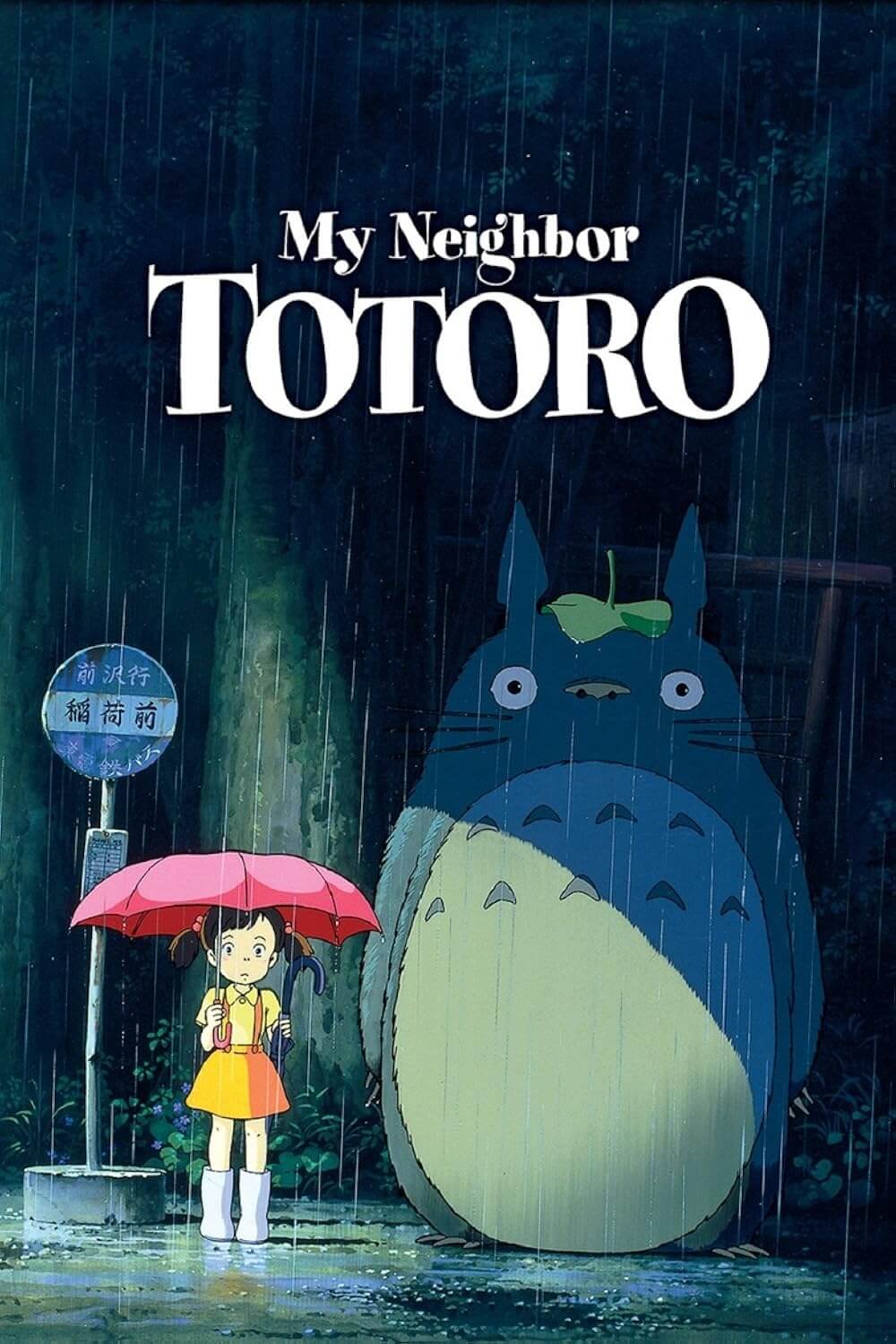

My Neighbor Totoro

Essay by Brian Eggert |

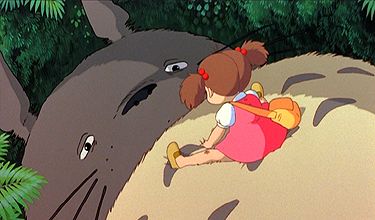

After following two forest spirits down the proverbial rabbit hole, Mei, a four-year-old girl complete with pigtails and endless curiosity, comes upon a massive clearing at the base of a conifer tree. There she sees a gargantuan ball of gray fur dozing in an alcove, its round form rising with every breath. She approaches its chubby, undefined, exposed arm and pokes it. The arm twitches. Mei giggles with excitement. She climbs on the beast’s belly, scooting forward to regard its kind, sleepy face. It yawns, and from the sound of its groan, she names it “Totoro,” a kind spirit that will only be seen if it wants to be. Mei never thinks to be afraid of the bear-sized Totoro in the woods, and she does not need to. This moment is not about danger, rather the sense of discovery as she pets its nose and quickly feels safe enough to curl up and take a nap on the Totoro’s furry paunch.

Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro is among the most delightful of all films. Driven by its pleasant nature and deceptive simplicity, the story remains free of harrowing conflicts, fast-paced action, or moments of deafening suspense. But whoever said a film needs violence and thrills to have adventure? Miyazaki contends that the discovery of magic and imagination in everyday life presents its own adventure. An incredibly personal effort for the Japanese animator, the film exemplifies Miyazaki’s desire to create animated works for everyone, regardless of age. He hopes to avoid demographic subcategorization, the diversifying of moviegoers by appeasing their increasingly niche-based interests. And so, Miyazaki seeks to communicate first with children in an honest and sincere way, which then, given his truthful approach, resonates with a universal audience.

Miyazaki opens his film with a cheerful song called “Stroll”, an elementary tune both happy and plain ringing beneath a title sequence alive with cute creatures, children marching, and bright colors. With this, Miyazaki sets the joyous tone and promises a blithe filmic environment for his audience. Safe for all viewers and particularly ripe for families, Miyazaki’s film wants to bring its audience together through a shared experience. When My Neighbor Totoro was in the planning stages, Miyazaki wrote that he wanted to make “a happy and heartwarming film, a film that lets the audience go home with pleasant, glad feelings. Lovers will feel each other to be more precious, parents will fondly recall their childhoods, and children will start exploring the thickets behind shrines and climbing trees to try to find a Totoro.” How accurate his foretelling would be.

Set in a time before the age of “virtual realities” like television and videogames, the story opens on a father driving his two daughters across the countryside in an overstuffed jalopy to their new home. Based on Miyazaki’s own experience as a child in the rural suburbs of Tokyo in the 1950s, the story’s exact setting remains pointedly imprecise. Miyazaki hoped to evoke a simpler time “before television”, so notice how the only technology that appears onscreen is a telephone. Not even a radio penetrates the purity of the surroundings. There are only farmland and rice fields, bicycles and dirt roads, ancient shrines and colossal trees. Miyazaki’s Spirited Away would later mirror this opening, with a family traveling to a new home, and the child escaping the anxieties therein through fantasy.

At eight-years-old, Satsuki Kusakabe is the elder sister to the impetuous, squeaky-voiced Mei. They arrive with their father, Professor Kusakabe, at their new home in the countryside where they can be closer to their mother, who recovers in a nearby hospital from spinal tuberculosis. The home is half traditional Japanese, half-Westernized, though it has not been lived in for some time. Their father, an archeology lecturer at the university, busies the children by telling them to look for “soot gremlins”. Satsuki and Mei scurry around the house and outdoors, laughing and playing, exploring their new home, when all at once they hear a shuffle and a swoosh. Was that the “soot gremlins”, or possibly, as Dad suggests, a ghost? An elderly neighbor woman the girls have been instructed to call “Granny” corrects their father, saying that the “soot sprites” are likely to leave once the family is settled. So Satsuki and Mei instinctively scream at the house’s empty rooms in unison, hoping to shake the fuzzy balls of black with eyes out of hiding. Granny says she used to see them too, when she was young.

In these first scenes, Miyazaki establishes a wounded but caring family where imagination is supported by their parents, building an environment of creativity and a celebration of childhood. The wild forest surroundings and potential presence of ghosts is never a cause for fear; rather they present exciting phenomena for only Satsuki and Mei to investigate. This is magic that only children can see, and for the viewer, this magic may be real within the story or may be figments of the children’s imaginations. Miyazaki sees no difference between the two; both types exist in their own ways. But in either instance, the fantastical happenings of the film are augmented through the eyes of a child, whether merely looking through the hole in the bottom of a “stupid bucket,” or observing an impossible forest creature slumbering in a wooded grove. One afternoon, with Satsuki off at school and Dad working in his office at home, Mei plays in the yard. She sees a small, white, semi-transparent bunny-like animal gathering acorns and she follows it into the woods where she finds the Totoro. She dozes with the creature in safety for the duration of the afternoon, and when Satsuki and Dad find her asleep in the woods, Mei tells them all about her experience. Satsuki believes the name “Totoro” comes from Mei’s mispronunciation of “totoru”, the Japanese word for troll, which Mei probably learned from the copy of Billy Goats Gruff that her mother reads them. Satsuki too would like to see the Totoro, and Dad has no qualms about his children believing in such things, but both have their doubts that Mei saw anything at all.

On a rainy evening when Dad forgot to take his umbrella to the university, Satsuki and Mei decide to meet him with one at the bus stop. Tired, Mei rests piggybacked on Satsuki. The hour grows late and the bus stop light illuminates the girls in the emerging darkness. All at once, lumbering peacefully from within the woods, Mei’s King Totoro, as it is called, joins the girls at the stop. Given the rain, Satsuki offers the creature an umbrella to hold. The Totoro accepts and quivers with delight at the sound of the raindrops pattering against the umbrella top. Then the Totoro jumps up and down to send a sheet of drops collected by trees surging down. The sound is immaculate. From down the road the bus finally arrives, but not their father’s bus. This is the Cat Bus, a twelve-legged creature with headlight eyes and furry seats. When the Totoro steps onto the living transport, the audience can do nothing but smile from ear to ear at the wonder of the moment.

The fantasy components are the most innocent and effortless in the film, while the scenes involving the mother character show the truth of infirmity. But Miyazaki does not dwell on sickness as a precursor to death; he acknowledges its existence in the real world and with ease asks his audience to accept it. In the film’s only scene of tension, Mom must remain at the hospital during the family’s planned weekend together, and in a flash of frustration, Satsuki yells at Mei, telling her to grow up, which in their family acts as a powerful insult—like death for a child. Hurt, Mei leaves on her own to visit her mother and gets lost along the way. The townspeople conduct a search, but Satsuki must beckon King Totoro and the Cat Bus for help before they find her. Miyazaki suggests that the unadulterated imagination of children is their safeguard, their saving grace, and the device through which they cope with unfortunate realities around them.

My Neighbor Totoro contains no plot per se, beyond situation and discovery. There are no threats or danger. Certainly, the forest spirits pose no hazard. Though the idea of ghosts and spirits fill the dialogue, their presence never feels menacing in any way. Consider how the Totoros sleep during the day and remain active at night. When Satsuki and Mei go exploring with the Totoro family, clinging to the King’s belly as it hovers on a magical top across the countryside, it occurs at night. And when the girls engage in a germination dance with the Totoros to raise their planted acorns into seedlings, that too happens at night. Yet Miyazaki avoids any hint of a Dark vs. Light dichotomy. Nighttime does not mean scary and evil. There is no malevolence in this film. Totoros are nocturnal and that is simply a truth of Nature. Not even the father worries about the girls believing in Totoros, whereas other children’s movies often make the parents into skeptics who in the last scene finally believe what their children were telling them all along. Perhaps this is because Miyazaki trusts the innocence of children, imagination, and Nature more than Westerners ever could.

Following currents in Miyazaki’s past and future work, My Neighbor Totoro ascribes to an ecological consciousness through the elements of fantasy and setting. The ambiguous backdrop of the story, for example, takes place in a past when trees like the gigantic confer could still exist. And this past seems directly linked to a strong imagination in Miyazaki’s films; whereas the technology-ridden present is deficient of imagination thanks to virtual entertainment. Professor Kusakabe notes that the trees come from “the time when trees and people used to be friends”, suggesting that industrialization has begun and soon such trees will be claimed. The setting amalgamates several real-life forests, including those from Miyazaki’s home in Tokorozawa and the home of art director Kazuo Ogaomes in the northern city of Akita. Such forests no longer survive in rural Tokyo, and so the sort of child who is bewitched by them cannot either. In any case, through the title and story, Miyazaki reminds his audience that the forests and the spirits within are our “neighbors,” and that being neighborly is not only limited to humans but to Nature.

Miyazaki invented the concept of forest spirits called “Totoro” for the film, combining imagery associated with bears and owls for the final design. As a child, Miyazaki used to dream of fearsome yet friendly creatures living in the forests. When he eventually sketched out his model for the Totoro, what he created was an animal now ingrained into Japanese society. Most toy shops in Japan carry plush Totoros today, and so Japanese children now see the round, fluffy creatures in their own dreams. The Totoro’s appearance is so clever and yet so simple. The smaller ones have almost no features aside from their round shape, the pointy suggestion of ears, and plain eyes. The blue middle-sized Totoro has more features, including a nose, limbs, and defined fur on its breast. The King Totoro towers over the others, its form all the more iconic and adorable because of its exaggerated size. Its whiskers stick out like a cat’s, and its pudgy limbs have claws that seem dedicated to the task of scratching its rotund torso.

For further inspiration, Miyazaki based Mei and Satsuki on himself, with Mei representing his age when he realized his own mother was ill and hospitalized with spinal tuberculosis, and Satsuki as his age when he began to grow up because of the ordeal. But Miyazaki is also evident in the young neighbor boy, Kanta, who is shown making wooden model planes; the director’s family owned an airplane parts shop, so Miyazaki was fascinated with aviation from a young age. The director chose female protagonists because of his evident feminism, derived from spending time in the hospital with his mother, an outspoken social critic at home. Those impressions stayed with him through adolescence and into adulthood, and eventually, he combined his extraordinary childhood dreams with his familial experiences into the outline for My Neighbor Totoro.

Miyazaki pitched his film to executives at Tokuma Shoten, of which Studio Ghibli is a subsidiary. They rejected the project as too risky. The film’s producer, Toshio Suzuki, suggested they reduce the risk by releasing the proposed picture on a double-bill with Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies, another risky anime about WWII atrocities in Japan. Though the double-bill failed to earn remarkable profits at the Japanese box-office, Ghibli opted to license a line of plush toys based on the Totoros. Only when the dolls were released in Japanese stores did Ghibli begin making money from the film’s release; moreover, the bountiful and ongoing merchandise sales have sustained the studio and allowed it to flourish. As the toys sold more and more, the film gained further attention from younger audiences wanting to know where their Totoro doll comes from.

My Neighbor Totoro has become increasingly adored over the years as audiences the world over are exposed to the joy within. Landmark Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, director of Ikiru and Seven Samurai, named it one of his 100 favorite films in a list compiled shortly before his death in 1998. When Miyazaki’s admirers at Walt Disney Company purchased the home video distribution rights in the mid-1990s and exposed the film to a wide Western audience, the universality of Miyazaki’s animation was apparent. However, minute cultural signifiers lost in translation prevent some audiences from making the leap into Miyazaki’s material. The statues and shrines, largely protective deities that appear on the roads in the film, suggest the characters will be safe in their company; even without knowing the names of the deities, the implication should be clear to most viewers. Also, Western audiences do often question a bathing scene between the Kusakabe’s father, Satsuki and Mei, since the type of family unity required for communal bathing is largely absent in the West. But those who watch a scene like this and feel uncomfortable, or see only abuse versus the innocence of familial harmony or parental love for one’s child, reflect the corruption of their own mores and expose their intolerance for understanding other cultures.

Miyazaki’s film is about imagination and family in their purest, most innocent forms. He wants to awaken his viewers to realize that within the real world there exists magic for those with the imagination to see it. When consumed by fears such as those of illness and death, which are very adult concerns for Miyazaki, a person cannot see the magic in the everyday world; only as a child, when such fears are nonexistent, will the Totoros emerge from the woods. Through these themes, Miyazaki teaches his audience to accept fear and Nature as realities of life. Once a person accepts them, they remain free to discover the more wondrous features of the world abound, magical or natural. Miyazaki’s approach is bold, given the appearance of the Kusakabe’s ill mother, but he respects children enough to trust that their resilience will get them through it. Only Pixar Animation Studios, in their 2009 film Up, dared depict such malady and ultimately death in a children’s film, because only they respect their audience as much as Miyazaki does.

The true test of animation is making it feel real. Without a sense of reality within an animated film, it has no purpose, no platform to work against. Miyazaki beautifully incorporates the details of his characters and their real-world to demonstrate his deep humanism and deeper imagination, as well as his regard for an audience that can absorb a film such as My Neighbor Totoro and grasp its density. The genuine family and its scenery feel so incredibly tangible within the film that the Totoro’s presence is made all the more marvelous for its distinction. The result is one of the most joyful, charming films ever made, fully capable of swelling the viewer’s heart and bringing them to laughter in the same moment. But because the medium presents a world of “just cartoons”, the film risks becoming an escape free of profound emotional connection to its audience. Miyazaki’s artistry and magic flourish because he brings animation back from the medium’s intrinsic detachment and re-engages the viewer with the power of his storytelling.

Bibliography:

Cavallaro, Dani. The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Mcfarland: 2006.

McCarthy, Helen. Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press: 1999.

Miyazaki, Hayao. Starting Point: 1979-1996. VIZ Media. 2009.

Odell, Colin & Michelle Le Blanc. Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, Oldcastle Books: 2009.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review