The Definitives

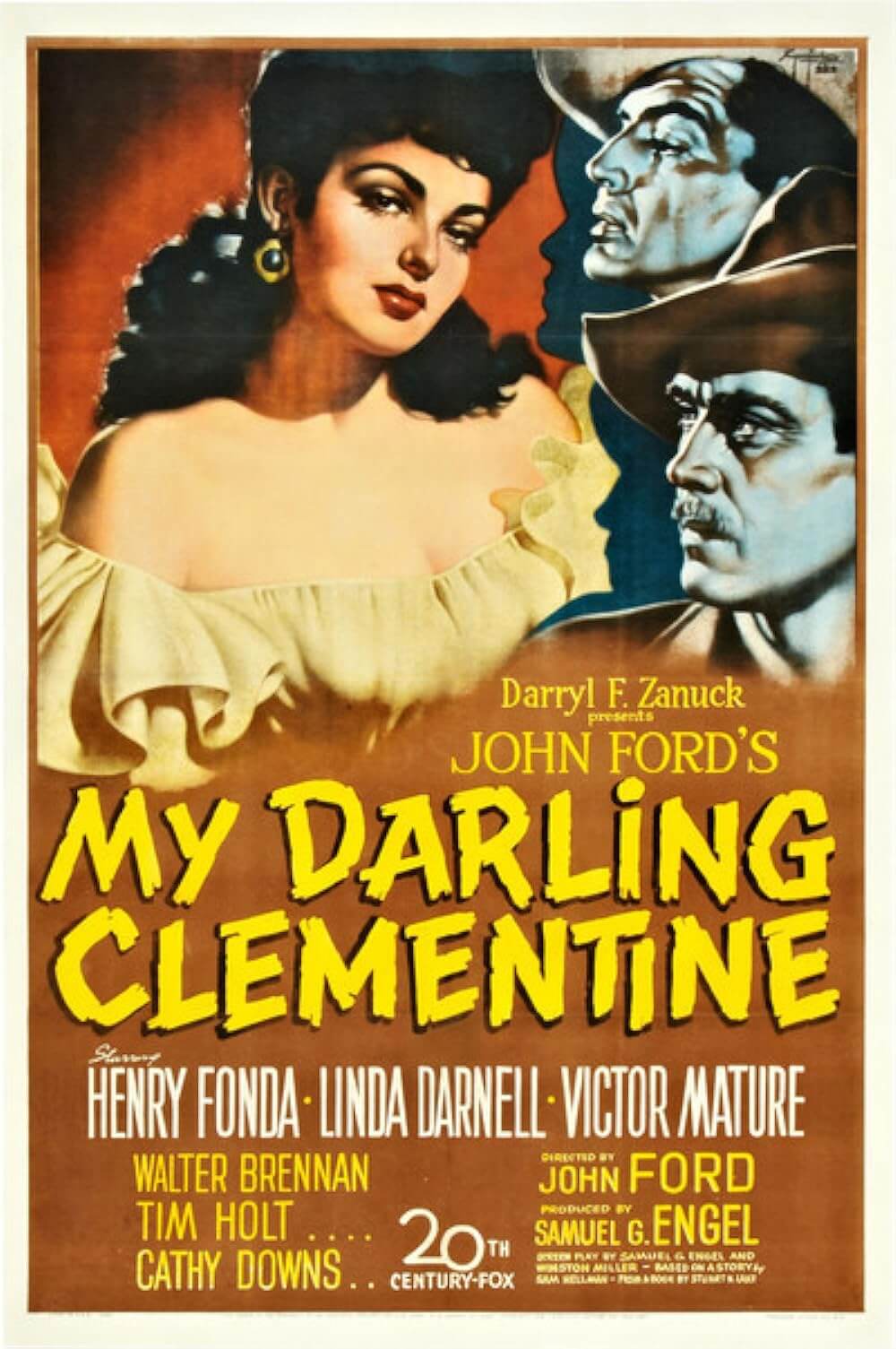

My Darling Clementine (1946)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Chronicling history by means of the Western, the one genre American cinema can claim to have pioneered, John Ford’s depiction of the West pumped with the blood of Manifest Destiny, the dreamy expression coined by nineteenth-century writer John L. O’Sullivan to spread “the great experiment of liberty” over the continent’s horizons. Ford’s ideological vision derived its foundation from utopian imagery found in American painting and the majestic geological formations of Monument Valley, his narratives created by Western mythos. His efforts span fifty years and well over one-hundred films, institute Western archetypes through a breadth of classical filmmaking, and establish a romantic form that subsequent films, Western or not, have used like a blueprint for great storytelling. Among Ford’s best films, and there are many, rests 1946’s My Darling Clementine, his gentle and endearing look at what is now the tall tale of Wyatt Earp’s heroism at Tombstone. Though boasting historical accuracy, the film washes over truth to instead achieve Ford’s romanticized view of the West—a land in need of cultivation and civilization, a territory of disorder requiring a hero to bring it law. A theme expanding his career, no other Ford work handles this thesis with the temperance and allegorical poetry that make the film stand out amid the masterworks of this great American artist.

Driving cattle to California with his brothers Morgan (Ward Bond), Virgil (Tim Holt), and youngest James (Don Garner), Wyatt Earp, played with calming singularity by Henry Fonda, takes reprieve from the trail with the elder two for a shave in the nearby town of Tombstone. Named after a marker of death, the town’s unruly chaos befits its reputation for having “the biggest graveyard west of the Rockies.” The saloon thrashes with hootin’ and hollerin’ night life, and the sounds of drinking, music, and gunfire. “What kinda town is this?” Wyatt asks, “A man can’t get a shave without gettin’ his head blowed off.” His face sporting a lather beard after stray bullets strike the barber shop, Wyatt finds the local law no help and takes out the responsible drunken miscreant himself with a single thump to the head, dragging him out by the heels, eager to finish his shave. The Land of Milk and Honey, sour around Tombstone, has a harshness Wyatt mentions early in the film. After retuning from town, the Earp brothers find James killed, shot in the back, their cattle rustled. Wyatt takes the town Marshal job the mayor offered, and makes Morgan and Virgil his deputies. Unquestionably, the Clantons are responsible for the murder—the Old Man (Walter Brennan) and his boys, the lot bearded and rugged. Wyatt has dealt with their kind before. “I figured on stickin’ around awhile. Got myself a job,” Wyatt explains, “Marshalin’.” The snake-like grins fall from the Clantons’ faces when the new Marshal introduces himself for the first time, his name already known throughout the region: “Earp. Wyatt Earp.”

Ford’s devotion to the idealistic grand push across the frontier into God’s Country remains his omnipresent signifier of the American identity. Addressing the unhinged nature of the West, either through its conquering or exploration, resides at the center of every Western, though often abstracted by plot devices as to avoid repetition. Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine comes from the East and must break Tombstone and its lawless inhabitants like a wild horse before he can continue. Ford even avoids suggesting Earp’s duty is lawful, rather “strictly a family affair” whereby law is employed for revenge—an entirely basic, human motivation. A fervent American, Ford proudly invested his career in the Western genre, designing its framework for cinema. He took delight in expounding his nostalgic pride in the communal foraging of the Golden West, which was immediately viewed as heroic by Americans. Spoken in 1901, the words of Vice President Roosevelt solidified such feelings: “The conquest and settlement of the West has been a stupendous feat of our race for the century that has just closed. It is a record of men who greatly dared and greatly did; a record of wanderings wider and more dangerous than those of the Vikings; a record of endless feats of arms, of victory after victory in the ceaseless strife wages against wild man and wild nature. The winning of the West was the great feat in the history of our race.”

Ford’s devotion to the idealistic grand push across the frontier into God’s Country remains his omnipresent signifier of the American identity. Addressing the unhinged nature of the West, either through its conquering or exploration, resides at the center of every Western, though often abstracted by plot devices as to avoid repetition. Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine comes from the East and must break Tombstone and its lawless inhabitants like a wild horse before he can continue. Ford even avoids suggesting Earp’s duty is lawful, rather “strictly a family affair” whereby law is employed for revenge—an entirely basic, human motivation. A fervent American, Ford proudly invested his career in the Western genre, designing its framework for cinema. He took delight in expounding his nostalgic pride in the communal foraging of the Golden West, which was immediately viewed as heroic by Americans. Spoken in 1901, the words of Vice President Roosevelt solidified such feelings: “The conquest and settlement of the West has been a stupendous feat of our race for the century that has just closed. It is a record of men who greatly dared and greatly did; a record of wanderings wider and more dangerous than those of the Vikings; a record of endless feats of arms, of victory after victory in the ceaseless strife wages against wild man and wild nature. The winning of the West was the great feat in the history of our race.”

Dynamics as clear as good and evil are the fundamental adhesive of Westerns, however, My Darling Clementine provides a middle ground in the form of legendary rogue, gunfighter, and philosopher Doc Holliday. Played with unbridled turmoil by Victor Mature, the character embodies the potential corruption for those who seek Manifest Destiny. And if Wyatt Earp exemplifies the progressive build from Wild West to civilization (a shy man, the West is equally hesitant but ultimately willing to progress forward), and Old Man Clanton the epitome of Western criminality, then Doc Holliday hangs in the balance between them as the personification of the dying Wild West, coughing blood from tuberculosis, spending his nights with a prostitute, Chihuahua (Linda Darnell). Even the title infers the morality play therein, as opposed to the gunplay exploited by most Westerns, by contemplating the deepest vulnerabilities of its characters, specifically those near to Clementine. The film could easily take the name of John Sturges’ 1957 actioner Gunfight at the O.K. Corral or George P. Cosmatos’ contemporary classic Tombstone; instead, it ruminates over emotional lessons and strong characters, all emphasized by Clementine’s passive-yet-turbulent role in the narrative. Ford’s concentration on the composition and development of the West, and not its professed violence, offers understated humor, tangible personalities, and significance beyond the genre’s traditional mainstays.

Ford’s treatment of the film as a character piece, despite its straightforward plot, is apparent throughout Doc Holliday’s inner struggle. With reputation enough to silence a saloon upon his entrance, Holliday nonetheless befriends Earp though the lawman potentially threatens his unimpeded power in Tombstone. The catalyst to Holliday’s conflict arrives with Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs), who has come searching by stagecoach after Holliday abandoned her in Boston some time ago. She is a civilized woman traveling into the wild to find her man consumed by the West, sick with its disease, possibly unsalvageable. His love for her is clear, but he tells her to leave town. Meanwhile, Chihuahua sits by Holliday’s side, symbolizing the untamable sexuality of the territory. Earp is awestruck by Clementine; her simplicity and civilized disposition draws glances from everyone in town. Earp’s palpably smitten timidity inspires modest and cheerful moments from Fonda’s unassuming portrayal. Earp finds himself embarrassingly dolled-up by the barber with a silly new haircut and sprayed with honeysuckle perfume, no doubt for Clementine’s benefit, and yet he can barely ask her for a dance. Fonda lends humanist airs with his effortless performance, making his burgeoning and unexpected romance with Clementine all the more blissful.

Ford’s treatment of the film as a character piece, despite its straightforward plot, is apparent throughout Doc Holliday’s inner struggle. With reputation enough to silence a saloon upon his entrance, Holliday nonetheless befriends Earp though the lawman potentially threatens his unimpeded power in Tombstone. The catalyst to Holliday’s conflict arrives with Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs), who has come searching by stagecoach after Holliday abandoned her in Boston some time ago. She is a civilized woman traveling into the wild to find her man consumed by the West, sick with its disease, possibly unsalvageable. His love for her is clear, but he tells her to leave town. Meanwhile, Chihuahua sits by Holliday’s side, symbolizing the untamable sexuality of the territory. Earp is awestruck by Clementine; her simplicity and civilized disposition draws glances from everyone in town. Earp’s palpably smitten timidity inspires modest and cheerful moments from Fonda’s unassuming portrayal. Earp finds himself embarrassingly dolled-up by the barber with a silly new haircut and sprayed with honeysuckle perfume, no doubt for Clementine’s benefit, and yet he can barely ask her for a dance. Fonda lends humanist airs with his effortless performance, making his burgeoning and unexpected romance with Clementine all the more blissful.

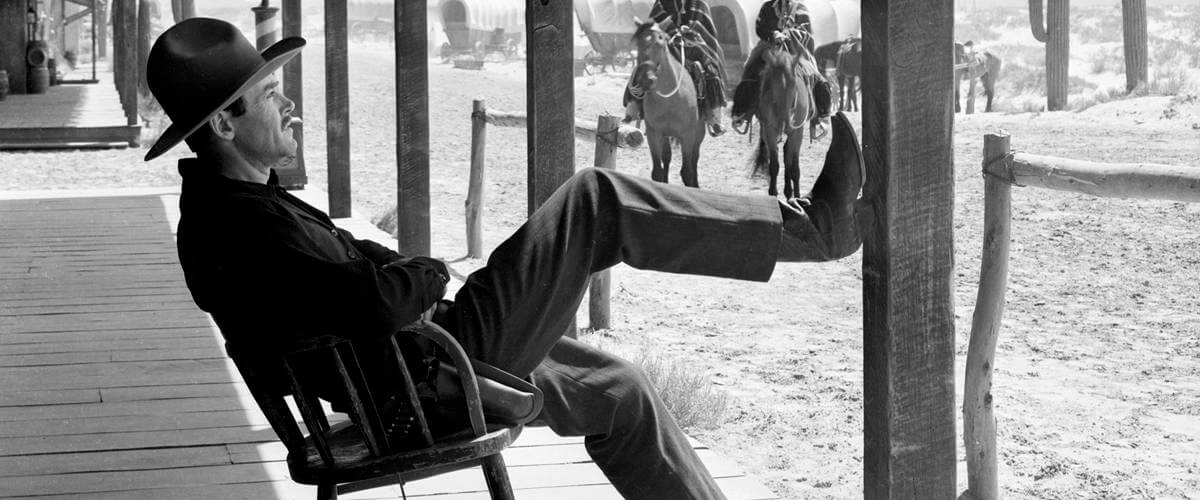

In an improvised scene, perhaps the film’s most famous, Fonda sits out on the porch in his chair, leaning on the back two legs in a balancing act, alternating his feet on the post in a seated ballet. A meaningless, intriguingly trouble-free and enjoyable moment, it sums up Fonda’s onscreen presence: Ford loved to shoot Fonda walking, and My Darling Clementine is filled with long, paced shots where Earp ambles along the expanse of a bar, or down the town’s sidewalk, each step deliberate, elegant, without swagger, ever certain. Fonda’s more than fifteen-year partnership with Ford delivered the director’s most soulful motion pictures. Titles like Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and this film each profited from the actor’s distinctive warmth and signature humanism. And while not as prolific as Ford and John Wayne’s partnership, the results are no less imposing. Downs’ screentime is insignificant next to her costars, though their characters seem to revolve around Clementine, anticipating her arrival, and polarizing to or away from her presence in Tombstone. She remains a background character, but one the others hinge upon. Holliday’s former nurse back when he thought himself a bona fide doctor, Clementine assists him in an operation after Chihuahua takes a bullet for pinning James Earp’s murder on the Clantons. Saving Chihuahua and validating himself as a physician again is Holliday’s sole shot at redemption. And for a moment, his patient seems all right, making him whole once more in Clementine’s eyes, until Chihuahua dies. Seeking the bottom of a bottle, Holliday later agrees to fight alongside Wyatt Earp at the O.K. Corral, and he volunteers himself into what he believes is a much-deserved death.

My Darling Clementine’s beauty settles in the emotional profundity of the action, how every bullet has meaning, and violence is paltry next to the fates of our heroes. The lyrical staging of Samuel G. Engel and Winston Miller’s screenplay, heavily informed by Ford, orchestrates Western tropes into a temperate drama, yet refuses to deny its audience the binding final shootout. The West, of course, destroys those not dedicated to progressive civilization: The Clantons die and so does Doc Holliday, as both parties reject Earp’s need to cut out the Wild from the West. Tragedy befalling the film’s conclusion, Ford volunteers Clementine as a bastion of hope in becoming Tombstone’s new schoolmarm, a symbol of education and therefore development, left behind like a marker of Earp’s passing-through. Aggrandizing the myths of the West—and in that ignoring the bitter realities he would explore before long in The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Cheyenne Autumn—Ford’s early Westerns, epitomized by the directness of My Darling Clementine, evoke the “Western utopia” illustrated by American painters. In the work of artists like Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, and Charles Schreyvogel, Western landscapes take the appearance of a fantastical realm, an Eden, a Nature that “predominates over its human inhabitants” and thus obliges humanity to rein it in. Evident from the picturesque scenery spanning his entire filmography, Ford followed the work of these painters, and was said to have kept a copy of the collected works of Schreyvogel at his bedside.

My Darling Clementine’s beauty settles in the emotional profundity of the action, how every bullet has meaning, and violence is paltry next to the fates of our heroes. The lyrical staging of Samuel G. Engel and Winston Miller’s screenplay, heavily informed by Ford, orchestrates Western tropes into a temperate drama, yet refuses to deny its audience the binding final shootout. The West, of course, destroys those not dedicated to progressive civilization: The Clantons die and so does Doc Holliday, as both parties reject Earp’s need to cut out the Wild from the West. Tragedy befalling the film’s conclusion, Ford volunteers Clementine as a bastion of hope in becoming Tombstone’s new schoolmarm, a symbol of education and therefore development, left behind like a marker of Earp’s passing-through. Aggrandizing the myths of the West—and in that ignoring the bitter realities he would explore before long in The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Cheyenne Autumn—Ford’s early Westerns, epitomized by the directness of My Darling Clementine, evoke the “Western utopia” illustrated by American painters. In the work of artists like Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, and Charles Schreyvogel, Western landscapes take the appearance of a fantastical realm, an Eden, a Nature that “predominates over its human inhabitants” and thus obliges humanity to rein it in. Evident from the picturesque scenery spanning his entire filmography, Ford followed the work of these painters, and was said to have kept a copy of the collected works of Schreyvogel at his bedside.

Realizing the vision of these artists, however, was not a matter of special effects, but finding the proper location. Most Ford Westerns were shot in Monument Valley, an unearthly place covering ground in Arizona and Utah where at spots the flat basin floor reach out to grab the sky. Harry Goulding established an outpost there in 1924, and, having paid $320 for 640 square acres, he assigned the task of photographing the massive buttes and seemingly impossible geological structures to Josef Muench. Muench later brought his images to Ford’s offices at United Artists and convinced the director to use the location in Stagecoach. The director never left. Monument Valley could be shot as boundless and hopeful as a Bierstadt painting, or as dark and desolate as the director’s dramatic needs required. My Darling Clementine features both interpretations. Ford’s use of Tombstone’s surrounding landscape contains painterly luminosity and trepidation, rendered all the more majestic and frightening by Joe MacDonald’s beautiful black & white cinematography. Consider the scene where the three Earp brothers first approach Tombstone; much of the frame encompasses an ominous terrain, a minor town surrounded by ill-fated clouds and surrounding hills. And afterward, when James is murdered, the reverse occurs; Wyatt sits over James’ wooden grave marker, the landscape transformed into a heavenly farewell.

Ford’s romanticism toward the Western did not end at scenery, but also included historical sentimentalism. Indeed, though the filmmaker sought to outdo the 1939 version of Frontier Marshal (then deemed the peak cinematic interpretation of Wyatt Earp’s story) by making a truthful account of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, My Darling Clementine strays far off the road of historical accuracy. This is curious, since in his early days as a filmmaker Ford reputedly spoke with Wyatt Earp, who by then was a living legend, and discussed the actual showdown. Using Earp’s undecorated testimony, though, would have abandoned the kind of myth-based narrative Ford sought to film. As the newspaperman in Ford’s more skeptical late-career masterpiece The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance declares, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The fact is, My Darling Clementine is a mess from a historical standpoint.

Ford’s romanticism toward the Western did not end at scenery, but also included historical sentimentalism. Indeed, though the filmmaker sought to outdo the 1939 version of Frontier Marshal (then deemed the peak cinematic interpretation of Wyatt Earp’s story) by making a truthful account of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, My Darling Clementine strays far off the road of historical accuracy. This is curious, since in his early days as a filmmaker Ford reputedly spoke with Wyatt Earp, who by then was a living legend, and discussed the actual showdown. Using Earp’s undecorated testimony, though, would have abandoned the kind of myth-based narrative Ford sought to film. As the newspaperman in Ford’s more skeptical late-career masterpiece The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance declares, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The fact is, My Darling Clementine is a mess from a historical standpoint.

Several biographers insist the Earps were less heroes than they were aggrandized killers. Known throughout the West as “pimps” and certainly not dignified lawmen, the real brothers ran whores, and were often accused of murder and horse thievery. James was the eldest brother, whereas in the film, for dramatic reasons, he is shown as a young and innocent victim worth avenging to the last bullet. Recollections of the Earps’ time at Tombstone, specifically the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, are even more conflicting—the events so muddled by contradictory accounts that Ford, always the romantic, was left to spin his own yarn about good and evil without offending any legitimate evidence. Shot like a “clever military maneuver,” the shootout plays slowly, theatrical dialogue punctuating the tensions and measured advances of the gunmen. Described by one historian as an assertion of power by the Earps, the real gunfight was fraught with ethical and legal ambiguity, and it was over before anyone knew what had just happened. In the film, Doc Holliday and Old Man Clanton are killed. As it happens, they were not. Nor was Wyatt the marshal of Tombstone; that was his brother, Virgil. And what followed the gunfight was not praise for Wyatt Earp the Hero, but a murder trial with the Earps as defendants.

Would the film be better had it followed history? Do its factual detours somehow diminish the experience? Not in the least. Our entire view of The Wild West is told by the winners, themselves scoundrels that could be accused of legal and moral debasement, had there been any law that far out to monitor them. Often inventing their own rules, those who pioneered the continent’s geographical mysteries were free in a way that seems abstract now. As for John Ford’s early Westerns, pretending humanity regulated itself by a just and fair system during that era was a storytelling standard. As years passed, we began to look back at the time as uncivilized, our unscrupulous management of Native Americans atrocious, and the heroes born from the period corrupt. But Ford’s Westerns still wishfully lacked moral uncertainty when My Darling Clementine was made, its central hero righteous, its villain unquestionably evil. History might not see eye to eye with the film’s story, but it delineates the romantic American identity Westerns sought to enable, onto which John Ford branded to his name.

Would the film be better had it followed history? Do its factual detours somehow diminish the experience? Not in the least. Our entire view of The Wild West is told by the winners, themselves scoundrels that could be accused of legal and moral debasement, had there been any law that far out to monitor them. Often inventing their own rules, those who pioneered the continent’s geographical mysteries were free in a way that seems abstract now. As for John Ford’s early Westerns, pretending humanity regulated itself by a just and fair system during that era was a storytelling standard. As years passed, we began to look back at the time as uncivilized, our unscrupulous management of Native Americans atrocious, and the heroes born from the period corrupt. But Ford’s Westerns still wishfully lacked moral uncertainty when My Darling Clementine was made, its central hero righteous, its villain unquestionably evil. History might not see eye to eye with the film’s story, but it delineates the romantic American identity Westerns sought to enable, onto which John Ford branded to his name.

When members of the Screen Directors Guild (a precursor to the current Directors Guild of America) assembled in 1950 to unite against their president Joseph L. Mankiewicz, whom they suspected a communist, Cecil B. DeMille (The Ten Commandments) led the rally, largely a whisper campaign that elevated into a loud march. John Ford stood up at the meeting and introduced himself: “My name is John Ford. I make Westerns.” Ford thus identified himself as an American making an American genre, and so, for the McCarthyism-driven men in attendance, his words rang fair and true. “I don’t think there’s anyone in this room who knows more about what the American public wants than Cecil B. DeMille—and he certainly knows how to give it to them.” Ford stopped for a moment, looking directly at DeMille, “I don’t like you, C.B., I don’t like what you stand for and I don’t like what you’ve been saying here tonight.” What followed was Ford, a living embodiment of American ideals, affirming that McCarthyism was un-American, and at least for one night, one of his friends would not be afflicted by its disease. Mankiewicz retained his position for another year, and, having won an Academy Award for Best Directing on A Letter to Three Wives a few months earlier, went on in the coming spring to win a consecutive Best Directing statue for All About Eve.

Orson Welles, director of Citizen Kane, what is now said by many to be the greatest movie ever made, was once asked to name his three favorite filmmakers; his much-quoted response: “I learned filmmaking by studying the Old Masters—and by that I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.” The above anecdotes offer some of Hollywood’s best wisdom about John Ford, perhaps the most prolific and celebrated of all Hollywood directors. He held residences at Columbia, Fox, MGM, RKO, Warner Brothers, and United Artists. By 1924, he completed his fiftieth film with the silent-era epic The Iron Horse, and from thereon out established his stature among Tinsel Town’s elite. Over his fifty-year career, the director won six Oscars, four for Best Director on The Informer, The Grapes of Wrath, How Green was My Valley, and The Quiet Man, and two more for his wartime documentaries. Not only was he an impeccable artist, he was a purveyor of great entertainment. Filmmakers are so often only one or the other.

Orson Welles, director of Citizen Kane, what is now said by many to be the greatest movie ever made, was once asked to name his three favorite filmmakers; his much-quoted response: “I learned filmmaking by studying the Old Masters—and by that I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.” The above anecdotes offer some of Hollywood’s best wisdom about John Ford, perhaps the most prolific and celebrated of all Hollywood directors. He held residences at Columbia, Fox, MGM, RKO, Warner Brothers, and United Artists. By 1924, he completed his fiftieth film with the silent-era epic The Iron Horse, and from thereon out established his stature among Tinsel Town’s elite. Over his fifty-year career, the director won six Oscars, four for Best Director on The Informer, The Grapes of Wrath, How Green was My Valley, and The Quiet Man, and two more for his wartime documentaries. Not only was he an impeccable artist, he was a purveyor of great entertainment. Filmmakers are so often only one or the other.

John Ford’s permanent authority in film history maintains his influence over today’s directors, most significantly those of the Western, few as they may be, by outlining the tools that every new addition into the genre either conforms to, or, in the case of Revisionist Westerns, uses as a platform to operate against. Ford’s themes and techniques could be found in any number of Westerns from his era or since, but My Darling Clementine is no less significant for it, because no other filmmaker imposes his touchstones with the same sense of craft as their originator. His film represents an unmatchable paradigm from which all subsequent Westerns evolve. That the picture also contains drama and joy and tenderness is one of cinema’s most welcome rewards.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Lindsay. About John Ford. Plexus Publishing, 1999.

Bernstein, Matthew; Studlar, Gaylyn. John Ford Made Westerns: Filming the Legend in the Sound Era. Indiana University Press, 2001.

Bogdanovich, Peter. John Ford (Revised and Enlarged edition). University of California Press, 1978.

Braudy, Leo; Cohen, Marshall. Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004.

Eyman, Scott. Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1999.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

McBride, Joseph. Searching for John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review