The Definitives

Mulholland Dr.

Essay by Brian Eggert |

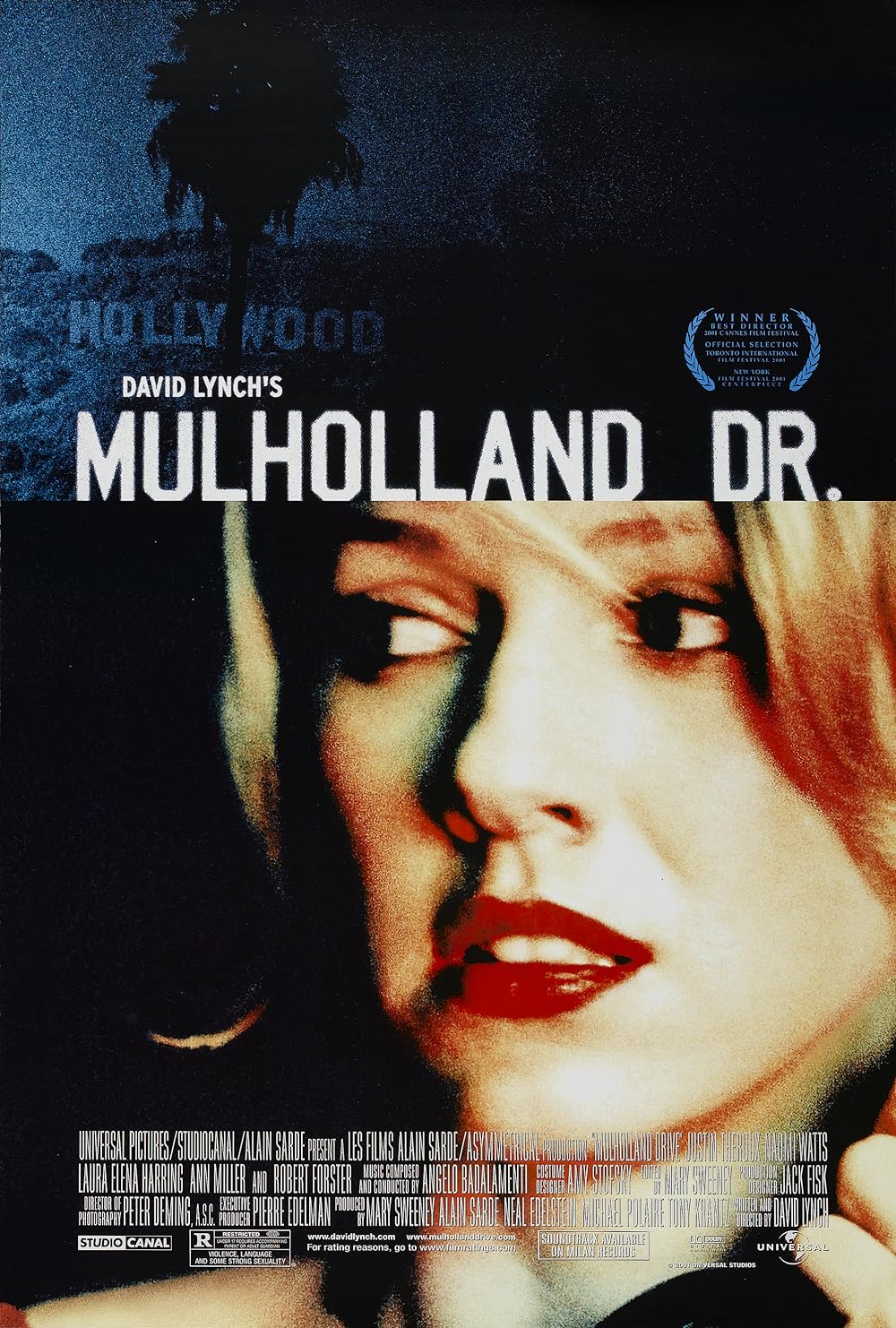

David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. defies all waking, verbalized logic. Its audience must commit themselves to being dream detectives, a cinematic métier in which we are required to decipher cryptic details and subtle clues, and then put them together in a way that makes sense to us, even if the way we understand the film cannot be fully articulated into words. A story of love, amnesia, shattered dreams, and through it all, a mystery set in Hollywood, the film contains a splendid puzzlework that must be worked out in the viewer’s mind. Any attempt at explaining the picture’s meaning through words gradually breaks down. No one, myself included, has entirely understood the film on the first viewing, nor has anyone gone on to assemble a satisfying, complete, and logical explanation for what happens in the film from start to finish. Mulholland Dr. journeys into the unconscious, where understanding does not require rational thought, and the film’s truth exists in how the audience feels toward and about it. At the same time, Lynch demonstrates how enamored he remains by Hollywood, its undying allure, potential for ugliness, and corruption. It’s a place where all of your dreams can come true or come crashing down in a nightmare. A film just as much about Hollywood as it is about the viewer trusting their skills as a motion picture dream detective, Mulholland Dr. is a rare kind of masterpiece.

Mulholland Drive (as it is more commonly written) was shot for a television pilot in another life that, too, was only a dream, a very bad dream. The pilot was completed about two years before Mulholland Drive premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2001, but ABC rejected the TV series for reasons that were never fully clarified by the director. Suffice it to say, Lynch was forced to cut an 88-minute pilot out of more than two hours of footage. The rejected rough cut, which was missing several important scenes and plot elements, later circulated throughout Hollywood on low-quality videotapes. Lynch resented that his project was being seen in this sub-par bootleg format more even than the pilot’s rejection. As time went on, Pierre Edelman from Studio Canal+ urged Lynch to use the existing footage and create a feature. Over the next year, Edelman secured the rights from ABC to make the film. Lynch then took roughly an hour of existing footage, shot additional content, and compiled everything into Mulholland Drive. Exactly how Lynch rearranged the unused pilot footage and what was newly shot remains a mystery on which Lynch refuses to elaborate. For the audience to know what was intended for the pilot would serve no purpose, according to Lynch, as the finished film bears no relationship to what was intended for the potential TV series. And yet, audiences cannot help but wonder.

The development from failed TV pilot to feature film forces one to consider Lynch’s creative process, if only for misguided clues into the film’s meaning—misguided because Mulholland Drive became something else entirely when it was transformed into a motion picture. Whatever Lynch had included in the original pilot exists as a part of the finished film, not an unrealized project. Rather, Lynch’s process of reshaping his footage would result in his most mysterious, lingering work, and the decisive example of Lynch’s method of artistic discovery. Lynch told Filmmaker magazine, “It was a most beautiful experience. Everything was seen from a different angle… It always wanted to be this way. It just took this strange beginning to cause it to be what it is.” Moreover, Lynch found developing a film much less complicated than an ongoing television series. In time, a TV series would be passed to other directors and writers to continue, a process Lynch compared to starting a sketch and then allowing other artists to complete it for him. By turning the failed pilot into a film, Lynch not only maintained creative control over his sketch, but he developed an entirely new work as well.

Discussing Mulholland Drive with other cinéastes or in written form becomes a thorny prospect, because the film resists a shot-for-shot logic and does not follow a traditional linear narrative. Much like the films of Terrence Malick or Stanley Kubrick, you must feel your way through your thoughts about it. As Lynch said about his similarly structured Lost Highway (1997), “Mystery is good, confusion is bad, and there’s a big difference between the two. I don’t like talking about things too much because, unless you’re a poet, when you talk about it, a big thing becomes smaller.” Conversations and analyses about Mulholland Drive can never fully include every detail within a chosen interpretation. The audience must discover what it means for themselves, despite lingering unanswered questions put to the director about what he intended. Of course, Lynch’s experiences shooting the pilot for ABC, its subsequent rejection and dismissive treatment by the network, and its eventual release into cinemas surely shaped the finished product. “Because of the particular problems I had with Mulholland Drive, I got certain ideas,” he explained. Lynch also remarked, “There’s an expression ‘where your attention is, that will be lively.'” And therein is the perfect description of how to watch the film. Each time you watch it, you concentrate on a specific aspect. Perhaps a particular character or scene exposes an entirely new theme that was not there on previous viewings. The viewer grabs from the stream—Lynch’s constant flow of satiric, frightening, and mysterious ideas.

If Mulholland Drive could be reduced to a single motif, it would be a slice of Tinsel Town. Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1955), a film with which Mulholland Drive has much in common, exemplified the town best with a desperate screenwriter narrating his story from death, and his fragile, desperate killer, the faded and irrelevant silent film star Norma Desmond. Hollywood is where everyone has lofty aspirations, has two faces, and lives in the company of shattered dreams. Among those dreamers was the director of water and power in Los Angeles, William Mulholland, whose vision for the city involved illegally diverting water away from Owens Valley into the San Fernando Valley. “There it is. Take it,” he said of the stolen water in 1913. Years later, in 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s celebrity status got his murder charge reduced to manslaughter after he used a bottle to sexually assault Virginia Rappe at a party, causing her death days later. It’s a town where failing actor Peg Entwistle leaped to her death from the “H” of the then-named Hollywoodland sign. Built on lies and stolen water, Los Angeles is haunted by the tragic lives of movie stars and forgotten bit players. And while the entire city would return to the dust of the Mojave Desert if the water stopped flowing, the fleeting dreams of its inhabitants remain. Aside from living near the actual Mulholland Dr. himself, Lynch chose the perfect title to represent his film.

The film follows wholesome, All-American would-be actress Betty (Naomi Watts), who has recently arrived in Hollywood and is ever curious. When Rita (Laura Elena Harring) appears in Betty’s apartment, having survived a car wreck on Mulholland Dr., Betty tries to help the amnesiac rediscover her identity. But as Betty and Rita trace the clues, Betty transitions into the jealous, drug-addicted actress Diane Selwyn, the lesbian lover of Camilla Rhodes (Melissa George), whom Diane envies as an idyll. Diane, too, is an aspiring actress. Rita, meanwhile, becomes Diane’s former lover Camilla. But this says nothing yet about Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), the director of a film called “The Sylvia North Story.” When he’s told by the Powers That Be that he can cast every part in his film except the lead role—curious figures, the Castigliani Brothers (Dan Hedaya and Angelo Badalamenti), show him a headshot of Camilla (appearing as Melissa George) and tell him “This is the girl”—he rebels. But his life soon falls apart: he finds his wife cheating on him (with “Gene Clean” pool man Billy Ray Cyrus), his bank accounts are frozen, and he’s relegated to a crummy hotel. Kersher finally gives in when he’s instructed by yet another curious figure, known as The Cowboy (Monty Montgomery), to accept Camilla in the lead role. And then there’s Joe (Mark Pellegrino), a hapless hitman whose motives are exclusively sleazy.

A literal key moment about halfway through the film transforms Betty into Diane and Rita into Camilla. This moment launches a divergent set of interpretations that ripple throughout the remainder of the film. Depending on how one understands the significance of what happens over the next half, each scene may have any number of unique meanings for its viewers. “For me, it’s a love story,” Lynch once said. But there are also Hollywood parallels to consider: At one point, after Twin Peaks was canceled, Lynch and his writing partner Mark Frost had considered adapting Anthony Summers’ book from 1985, Goddess: the Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe. While Lynch “loved the idea of this woman in trouble,” he said he didn’t like it “being a real story.” It’s undoubtedly no coincidence that Monroe—who often talked about being a Gemini, remarking on the duality of her behavior—was found dead under questionable circumstances in her bed, lying almost in the fetal position from an apparent drug overdose. How can we not think of Monroe when Lynch shows us Diane dead under similar suspicious conditions, and later Betty too?

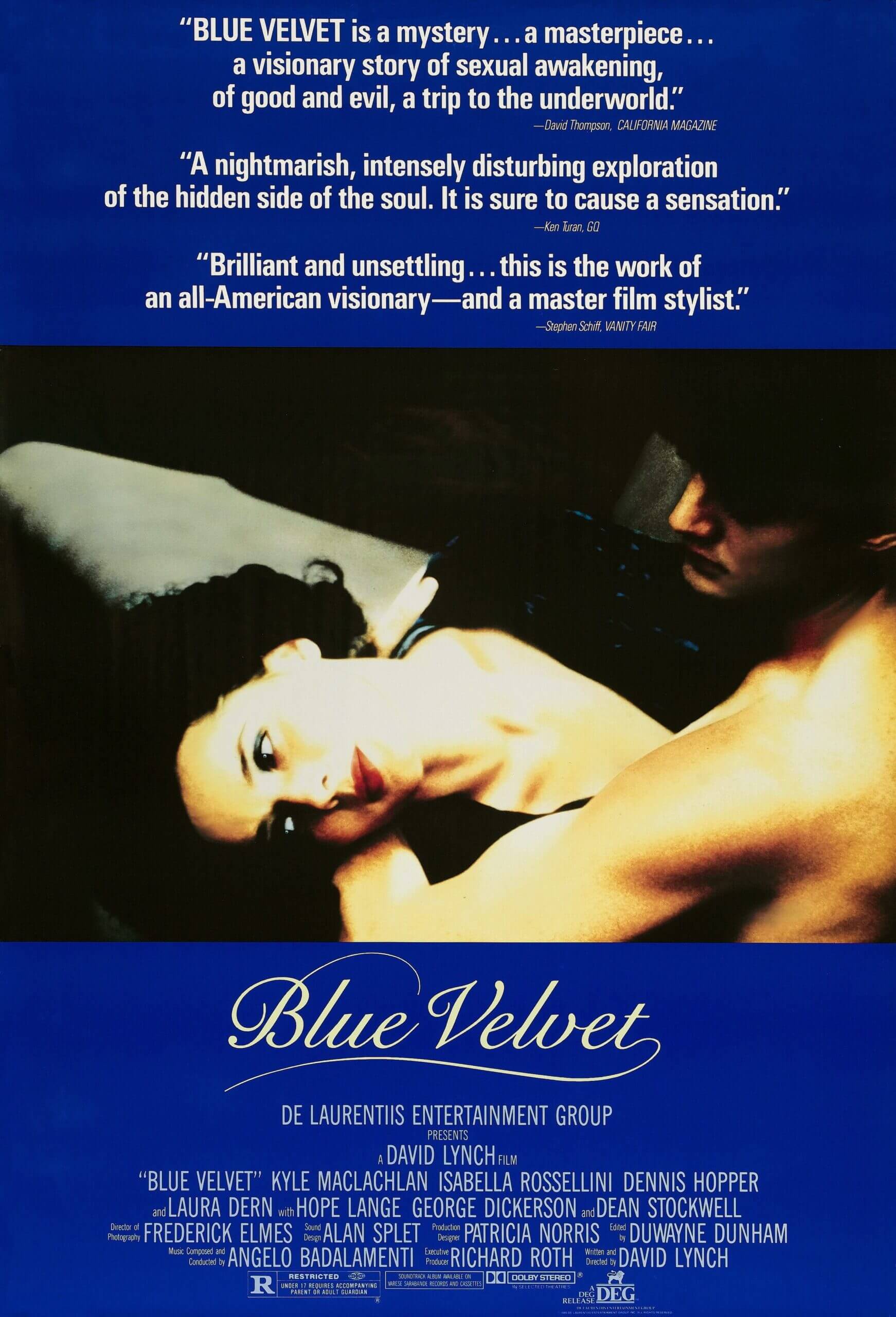

Mulholland Drive contains several Lynch-isms, from evocative imagery to scenes closely resembling those in his other films. In a (possibly?) Möbius strip structure used by Lynch on Lost Highway (1997), the film folds back on itself, forcing the audience to wonder where it begins and where it ends. Much like that film and his television series Twin Peaks, we must ask ourselves whether any given scene takes place in a dream or whether it’s reality. Mulholland Drive has a similar refrain to Twin Peaks‘ “Fire walk with me,” when characters announce, “This is the girl,” a line whose meaning changes each time it’s spoken. In other ways, the film relates to Blue Velvet (1986) in how both feature protagonists drawn to a detective story—and their curiosity subjects them to a dangerous, frightening underworld. Quirky, Lynchian humor also has its place in the film, mostly surrounding Adam Kesher’s storyline. And then there are moments where Lynch loses himself in the pure beauty of a moment. When Rebekah del Rio appears in Club Silencio and sings a haunting, Spanish cappella rendition of Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” Betty and Rita, bathed in the blue light of the club, begin to weep uncontrollably. Though we may not fully comprehend why this occurs, the power of the scene sweeps over us and brings us to tears as well.

Through these rigorous changeovers and questions of identity, Watts and Harring deliver unbelievably accomplished performances. Watts displays a range that, in time, would carry her talent into one of today’s best working performers, whereas Harring’s enduring mystery remains so, as the actor’s career has not taken off as Watts’ has—sustaining an air of obscurity about her characters, Rita and Camilla. Both performances were acknowledged and celebrated by critics upon the film’s release, which was received with glowing reviews and modest box-office results. At Cannes, Lynch shared the Best Director award with Joel and Ethan Coen, who won for The Man Who Wasn’t There, an equally mysterious and interpretable film. Acknowledging that Mulholland Drive was not a straightforward release with a closed narrative, Canal+ distributed a series of enigmatic clues such as “Who gives a key, and why?” and “What is felt, realized and gathered at the Club Silencio?” along with press releases and promotional material, submerging viewers in further mystery. Lynch admits the ten clues released in Canal + marketing and on home media releases are not decisive and were intentionally designed to be vague or just get people thinking. Indeed, people still cannot stop thinking about the film. And over time, Mulholland Drive has only grown in its assessments as audiences and critics have continued to mull over its meanings. Most recently, in 2012, the British Film Institute’s publication Sight & Sound ranked it on their fifty greatest films of all time list.

While countless interpretations could be drawn from Mulholland Drive, my own interpretation is that Betty and Rita are the dream. In reality, Betty is how Diane sees herself. Diane sees the glamorous Hollywood life right at her fingertips but cannot break through, whereas her vision of Betty shows a promising actress admired by all, including her would-be director. Diane blames greater conspiracies (“This is the girl”) and perhaps even something evil (the monster behind the coffee shop) for her own failures. She loves Camilla, but that love isn’t returned. She imagines herself with another version of Camilla, named Rita. Rita loves Betty and needs her to discover herself. At the end of Diane’s dream, the two find themselves in Club Silencio, clinging to each other, everlastingly in need of the other and entangled forevermore. In reality, Betty becomes a washed-up, drug-addled loser who ends up shooting herself. (It should be noted that Marilyn Monroe was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, an ailment that leaves the emotionally unstable victim desperate for the approval and attention of others. This description could apply to Diane as well.) Meanwhile, Camilla becomes a studio stooge, not unlike Monroe. Perhaps she’s turned into a studio tool, as identity-less as Rita becomes after her car wreck. But just as any interpretation of this film has holes and flaws, mine does too. As I suggested earlier, thinking your way through Mulholland Drive with any hope of logic is a mistake. This film must be felt.

Steeped in obscure, entrancing details and countless individual moments of beauty, humor, terror, eroticism, and any number of undeniable evocations, Mulholland Drive challenges audiences in a way few other motion pictures do. You could watch the film a dozen times and, each time trying to figure out a separate element, arrive at a dozen equally satisfying if somewhat maddeningly different, interpretations. Lynch maintains he did not set out to tease his audience with unanswerable clues; rather, he hopes they will “figure things out” for themselves. Such lofty demands represent an incredible trial to determine how much thought and feeling the viewer is willing to commit to their screening. Rather than just sit back and watch, Lynch expects active participants to process what he has created; and this act of processing occurs more during the film in a deeply felt reaction, as opposed to afterward during a logical development of analysis. For a moviegoer to accept not knowing and instead feel their solution to the film’s puzzle requires the most sophisticated kind of viewer, open to an experience created by a pure artist. How rare that Mulholland Drive endures as a picture that somehow remains irresistible and compelling with each viewing, yet refuses to surrender to any single interpretation.

Bibliography:

Rodley, Chris (edited by). Lynch on Lynch. Revised Edition. London: Faber & Faber, 2005.

Woods, Paul A. Weirdsville U.S.A.: The Obsessive Universe of David Lynch. 2nd ed. UK: Plexus, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review