The Definitives

Modern Times (1936)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

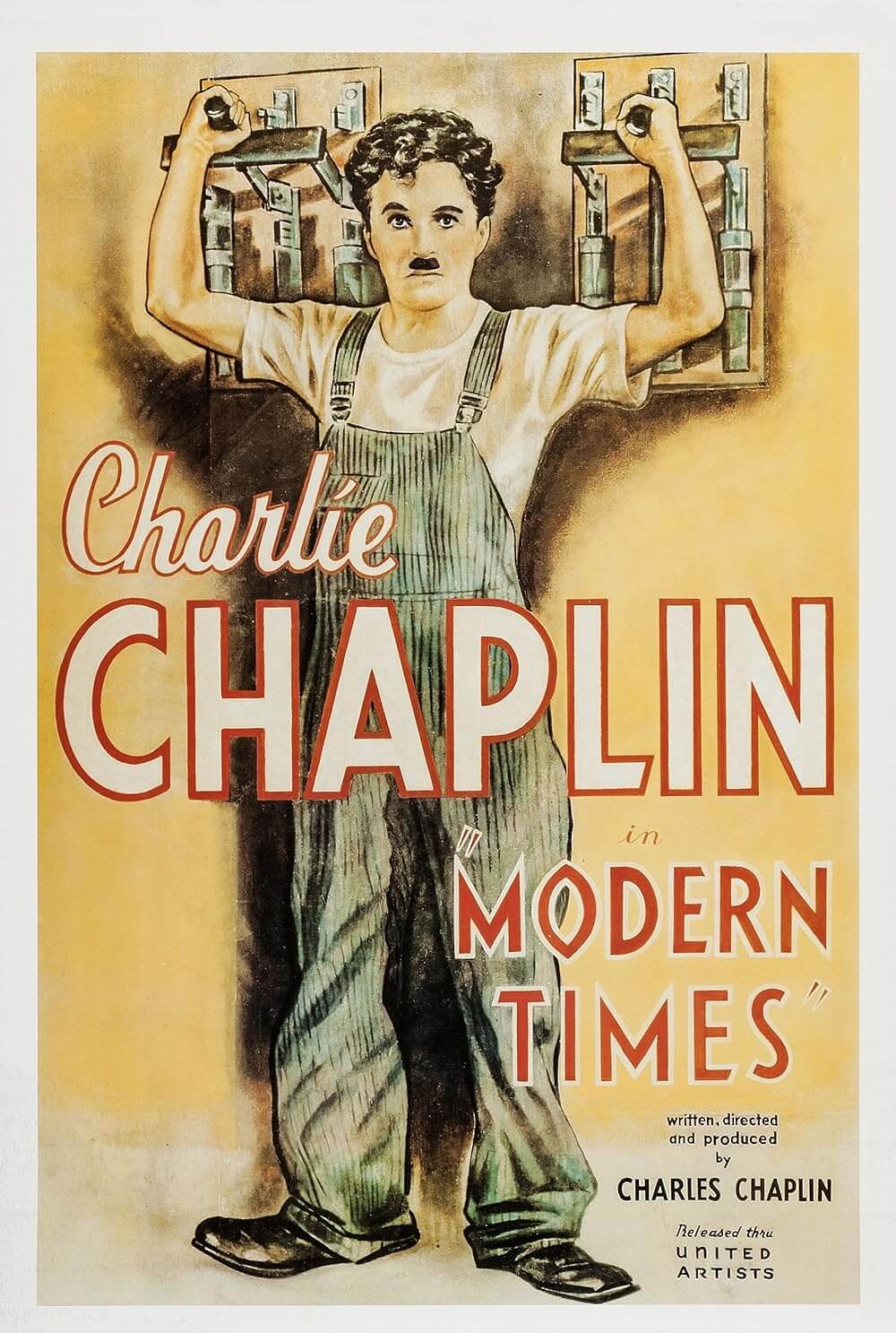

Asymmetrical in form, he cuts a distinctive figure. His derby hat rests upon his head at an angle, its slant accentuated by the straightness of his suspenders and the forced lines of his tight-buttoned coat. Air fluffs his baggy pants, which seem to tighten like a balloon knot at his ankles, where his over-sized shoes oblige his feet to point outward, causing him to waddle when he walks. Balancing himself, he carries a bamboo cane that maintains his posture. He looks as though his once sweet life has passed. His garb is tattered, and his eyes are dark, but his mustache is short and trimmed, and his demeanor is always gentlemanly. And yet, his good manners are married with a liberated sense of freedom and severance, displacing him as an outsider reliant only on his most human instincts. His appearance reflects this station, giving him an uneven silhouette, albeit immediately familiar and identifiable. This is the Tramp. This is Charles Chaplin. But more than an iconographic image of early cinema magic, more than a comedic pantomime or sentimentalist director, Chaplin provoked thought with his tender comedies. His ingenious 1936 picture Modern Times confirms this by illustrating how the human condition struggles under the foot of industry and technological advancement. His foreword: “Modern Times.” A story of industry, of individual enterprise—humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness. Chaplin explores how the average person must not only fight for contentment, but in an industrial world, we must fight to preserve our individualism against the rising tide of so-called progress.

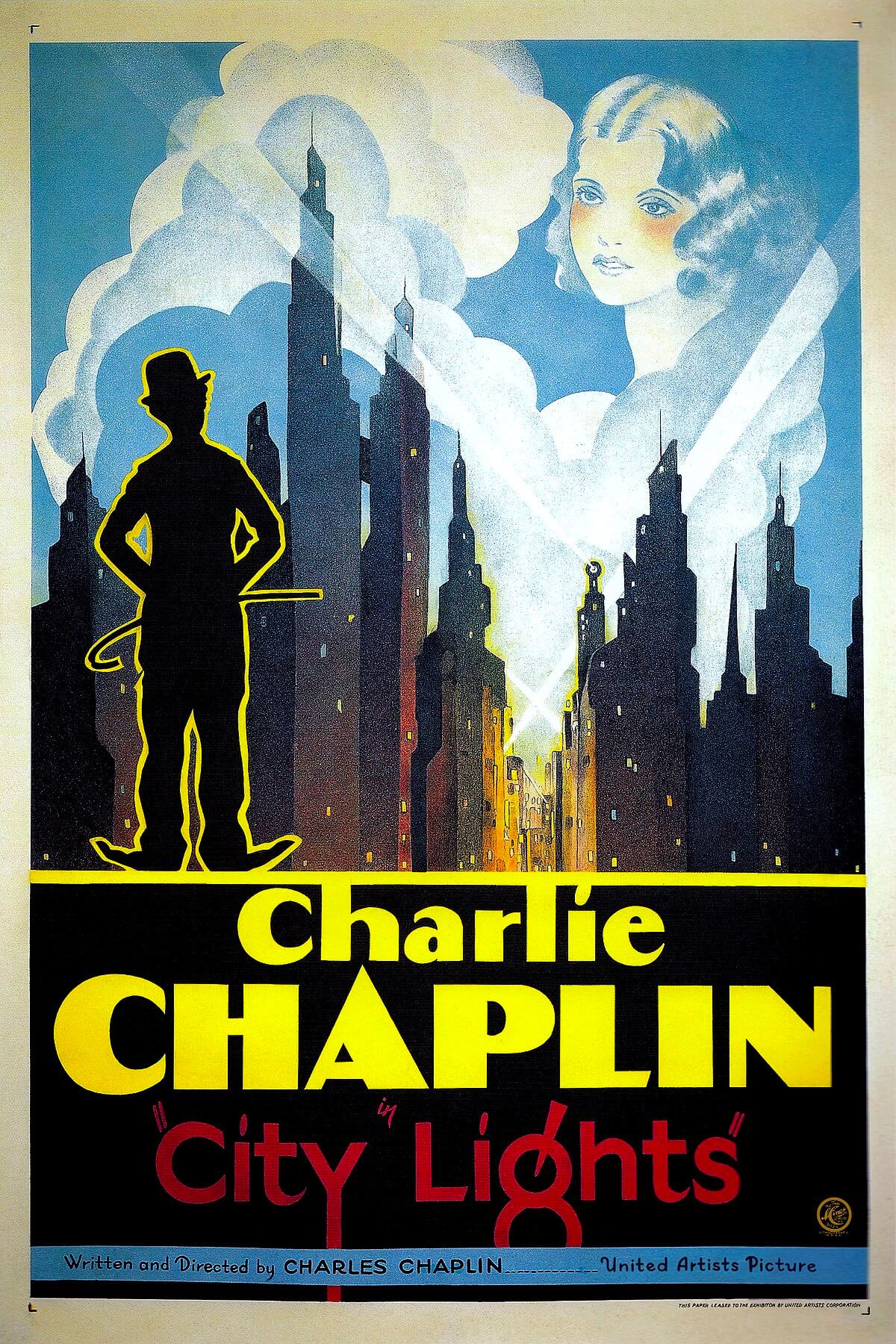

His message is conveyed through the universal rhetoric of comedy; invasive commentary is left on the wayside, which has left some critics to argue that Chaplin does not live up to his foreword’s promise. He satires the effects of industry according to how it fails humanist concerns. This is accomplished through the Tramp’s adventures, each of which could be whole two-reelers. Indeed, the film is episodic, taking the Tramp from place to place while maintaining a unifying theme of survival in the industrial, Depression-era world. To claim the picture lacks the emotional structure of Chaplin’s clear comedic melodramas (City Lights, The Kid), however, is an error. Accompanying our hero the Tramp is the “Gamin,” played by the delightful Paulette Goddard, Chaplin’s lover for a number of years until 1940. Gamin being the masculine French noun for mischievous or playful street urchin, Chaplin would later admit he should have called her gamine, the feminine form. Nevertheless, Goddard plays her as the perfect accompaniment to the established Tramp. Her first scene involves an act of Robin Hood-type bravery. She steals bananas for poor children, bringing them home to her family, which is soon broken apart by social services. She, too, becomes a vagabond, but eventually, she finds a kindred spirit in the Tramp. Together, the two are what Chaplin called “two playmates—partners in crime, comrades, babes in the woods.”

Chaplin describes these “woods” just after the opening credits, when he cuts to an image of marching sheep that fades into workers pouring off a subway terminal and into a factory. Centered amid the white sheep is a single black one moving along with the crowd, a clear reference to the Tramp. Cut to the inner factory where we see Chaplin, his black hair and short mustache immediately familiar, turning bolts on a conveyor belt. He struggles to keep up, moving up and down the line much to the chagrin of those succeeding him. A wrench in each hand, he twists two bolts at once on the assembly line, over and over in an endless rhythm. Lunch is called, and the belt stops, but the Tramp keeps twitching on pace uncontrollably, the after-effects of repetitious industrial labor infused in his motions. Meanwhile, the Tramp is chosen as the guinea pig for a new experiment, dubbed “The Billows Feeding Machine”—a state-of-the-art apparatus allowing workers to eat without a break, thus maximizing production. He stands before a mechanized Lazy Susan fit with gizmos that serve food directly into its subject’s mouth. Automated appendages push squares of meat; a rotator spins an ear of corn; a bowl of soup rises for easy sipping. Between courses, a pad wipes the face clean. Behind the scenes, Chaplin operated these devices himself, his hands at work just off-camera below. And so, of course, the machine malfunctions with the Tramp locked inside for a series of punishing mishaps, including soup in the face, force-fed bolts, and a violent cleaning.

Chaplin describes these “woods” just after the opening credits, when he cuts to an image of marching sheep that fades into workers pouring off a subway terminal and into a factory. Centered amid the white sheep is a single black one moving along with the crowd, a clear reference to the Tramp. Cut to the inner factory where we see Chaplin, his black hair and short mustache immediately familiar, turning bolts on a conveyor belt. He struggles to keep up, moving up and down the line much to the chagrin of those succeeding him. A wrench in each hand, he twists two bolts at once on the assembly line, over and over in an endless rhythm. Lunch is called, and the belt stops, but the Tramp keeps twitching on pace uncontrollably, the after-effects of repetitious industrial labor infused in his motions. Meanwhile, the Tramp is chosen as the guinea pig for a new experiment, dubbed “The Billows Feeding Machine”—a state-of-the-art apparatus allowing workers to eat without a break, thus maximizing production. He stands before a mechanized Lazy Susan fit with gizmos that serve food directly into its subject’s mouth. Automated appendages push squares of meat; a rotator spins an ear of corn; a bowl of soup rises for easy sipping. Between courses, a pad wipes the face clean. Behind the scenes, Chaplin operated these devices himself, his hands at work just off-camera below. And so, of course, the machine malfunctions with the Tramp locked inside for a series of punishing mishaps, including soup in the face, force-fed bolts, and a violent cleaning.

Chaplin believed machinery should benefit humanity, not remove humanity from the individual. When he returned to Hollywood after a year-long hiatus in 1932, he was taken aback by the “tyranny of the machine” and the dwindling spirit of Depression-era America. He blamed those who constructed machines for solely profit-making purposes rather than improving the lives of ordinary citizens. Chaplin would write, “Something is wrong. Things have been badly managed when five million men are out of work in the richest country in the world.” Chaplin questioned why massive factories produced a cheaper product faster if the process drives workers to the unemployment office. With so many struggling or out of work, who could afford the excess of consumer products being built? Since it was not a specific company (an obvious choice like Ford Motors) Chaplin sought to scrutinize, he avoids labeling the factory in his film. We learn neither the company’s name nor what they manufacture, as Chaplin prefers to target capitalism as a whole.

Despite Chaplin’s commentary, Modern Times is not a message film; rather, it is an exercise in human emotions in which the setting reflects the changing world. “The question is not whether the country is wet or dry,” Chaplin wrote, “but whether the country is starved or fed.” His concern is humanity’s place in a world where industrialization dehumanizes middle-class citizens. This is never more delightfully spelled-out than when the Tramp, having been driven mad by the monotony of tightening bolts, leaps into a port where his body moves effortlessly among the clockwork of gears inside. His body bends to fit every curvature, and he becomes a cog in the wheels of industry. When he emerges again on the factory floor, his madness sends him into a whimsical frolic, spraying oil in workers’ faces, twisting his wrenches on everything in sight that resembles a bolt. Outside the factory, the Tramp spots a woman with notably large breasts, punctuated by bolt-like buttons. He chases after her with a wild glint in his eye; his gag fulfills itself without the Tramp carrying out the suggested action.

Chaplin’s critics at the time saw the film as communistic as opposed to humanistic, the latter being the director’s true intention. Key scenes have been misread as serious commentary instead of comedic folly: The Tramp is institutionalized for his on-the-job breakdown and released shortly thereafter with a clean bill of mental health. Back on the street, he sees a rear distance flag fall off a truck. He picks it up and chases after, waving the flag to get the driver’s attention. Around the corner behind him, a communist rally turns and marches down the street, giving the impression that the Tramp leads the worker’s strike. However, Chaplin seems to preemptively say not to misconstrue Modern Times as a statement with this scene, but his critics—J. Edgar Hoover among them—came to that conclusion nonetheless. In the film, the Tramp is caught and thrown in jail for his assumed demonstration. Off-camera, Chaplin’s political reputation would come under an increasingly hot spotlight.

Indeed, Chaplin left the United States in 1952 after enduring years of persecution for his freethinking, free-voiced opinions about capitalists and politicians. His remaining years were spent at his home in Switzerland. An article in the April 1953 issue of Time wrote the following: Charlie Chaplin, British subject, surrendered his U.S. re-entry permit in Geneva and flew off to London. Chaplin had made his decision. The U.S. Immigration authorities had warned him that he would be subject to a screening exam, just as any other alien, when he returned. In his London hotel room he wrote his valedictory after 40 years of U.S. residence: “. . . Since the end of the last world war, I have been the object of lies and propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who, by their influence and by the aid of America’s yellow press, have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. Under these conditions I find it virtually impossible to continue my motion-picture work, and I have therefore given up my residence in the United States.”

How strange that Modern Times, along with Chaplin’s himself, was met with harsh disapproval. His concerns were with the basic needs and desires of humanity. Chaplin grew up in poverty, so his films often feature the Tramp struggling to find something to eat or cope with the daily reality of hunger. After the Tramp earns a release from prison for thwarting an escape, he refuses to leave since it affords him free shelter and three meals a day. Outside, the unemployed starve. When he’s forced out, he happily buys an exorbitantly large meal with no intention of paying, if only to get back into prison. Later still, back again on the outside, the Tramp gets a job as a night watchman. Burglars arrive not to ransack the store, but to feed themselves. “We ain’t burglars—we’re hungry.” Food even occupies the Tramp’s daydreams—his fantasy home includes a fruit tree at the window and a milk-producing cow that comes when called.

Chaplin resolves that people need human interaction, not more technology—a theme easily drawn from the Gamine’s presence. The Tramp and Gamine are like children, free of responsibility, while adults remain mindless and controlled automatons. Theirs is not a romantic bond; when they find a run-down shack for a home, the Tramp sleeps in a small attached barn while Gamine sleeps inside the main home. Their life together resembles children playing house. When they kiss, their kisses are bonds of deep friendship and togetherness. And while most Chaplin pictures conclude with the Tramp facing the world alone, always getting by on his own esteem, he keeps Gamine as a companion at the end of Modern Times. For the first and last time in the Tramp’s onscreen life, in the end, he is not alone.

Chaplin resolves that people need human interaction, not more technology—a theme easily drawn from the Gamine’s presence. The Tramp and Gamine are like children, free of responsibility, while adults remain mindless and controlled automatons. Theirs is not a romantic bond; when they find a run-down shack for a home, the Tramp sleeps in a small attached barn while Gamine sleeps inside the main home. Their life together resembles children playing house. When they kiss, their kisses are bonds of deep friendship and togetherness. And while most Chaplin pictures conclude with the Tramp facing the world alone, always getting by on his own esteem, he keeps Gamine as a companion at the end of Modern Times. For the first and last time in the Tramp’s onscreen life, in the end, he is not alone.

Released by United Artists, which Chaplin originated along with Douglas Fairbanks, D. W. Griffith, and Mary Pickford in 1919, the film’s production resisted an all-out committal to sound because Chaplin was more certain of his success within the voiceless theatricality of silent-era filmmaking. Long after the major studios had opted for sound, Chaplin released City Lights in 1931, earning rave reviews and box-office. Chaplin was committed to the idea that music provides background effects, while pantomime supplied the emotion. Dialogue was not necessary and would slow his process, thus hindering the film’s comedic effect. In interviews, he predicted sound pictures would last no more than a year; and a year later, when they did not disappear, he insisted that if talkies were to last, it would not be in his own pictures. During a five-year filmmaking hiatus, Chaplin fought with the reality that his pictures were no longer how films were made. And by the time production began on Modern Times in 1933, Chaplin had written a full script complete with dialogue, if only to keep up with his title’s setting.

Chaplin initially set out to make his first talkie, since most of his Hollywood contemporaries had made the leap years before. But had he followed through with his chatty script, Modern Times would not be the same film; it would fail in hypocrisy. Luckily, perhaps fearing modernization like the Tramp in his film, Chaplin resisted full-fledged sound and instead relied on synchronizing certain sound effects and voices. Whereas dialogue appears on infrequent title cards, the film features audible car horns, whistles, grinding gadgets, buzzers, and stomach grumblings. When Chaplin does use a voice, it comes from a disembodied source. Note how the factory owner speaks on a video screen, or how the salesman (“Your Speaker: The Mechanical Salesman”) arrives to demonstrate the aforementioned feeding machine and, rather than pitch the machine himself, he humorously plays the spiel on a phonograph. Modern Times critiques those who would so unreservedly jump into the new sound format.

To be sure, the sound effects are impersonal and communicated through filters, while their substance is often gibberish. The factory president who spends his time putting together puzzles in his office, for example, occasionally turns to his monitor and barks an order; we never see him actually speak in person, only on his screen, his head blown up to a massively authoritarian size. In the last hurrah, Chaplin finally allows his audience to hear the Tramp’s voice in a lovely take on the French tune “Titine,” sung at a posh soiree where the Tramp has secured a job as a performing waiter. The Tramp scrambles with his serving duties until he is forced to sing. Gamine quickly scribbles the lyrics onto his cuffs, but he loses them during his introductory dance routine. The result is an improvised refrain crooned with nonsensical pseudo-French words, illustrating the uselessness of specific dialogue in the presence of sound, but we fully understand the meaning of the song thanks to Chaplin’s pantomimic clarity.

Chaplin’s greatest achievements were as a visual performer, whether he was making sound films or silent. He followed Modern Times with The Great Dictator in 1940, and despite the inclusion of dialogue and lengthy political speeches, the scenes we remember are Chaplin’s pseudo-Hitler bouncing a balloon-globe into the air. Chaplin lived by the maxim that actions speak louder than words; specifically, he believed cinema an exclusively pantomimic artform—an opinion no doubt influenced by watching his mother perform in music halls throughout his childhood, and then advancing onto the stage himself at a young age. He told Time in a 1931 interview promoting City Lights, “Action is more generally understood than words. Like the Chinese symbolism it will mean different things according to its scenic connotation. Listen to a description of some unfamiliar object—an African warthog, for example. Then look at a picture of the animal and see how surprised you are.” Chaplin knew the Tramp’s charm rested in his wordless expression, as the character communicated emotions visually, therefore universally. Even though audiences had never heard the Tramp speak, and hearing his voice in Modern Times was revelatory, the film’s lasting achievements remain purely physical. Consider the impressive planning required to accomplish the scene where the Tramp roller-skates in an under-construction section on the fourth floor of the department store. Chaplin blindfolds himself as he glides about, moving gracefully and coming dangerously close to the edge of an open section of the floor. Certainly, this daring sequence holds significant artistic merit over any instance of sound by its choreography alone.

Not that Chaplin was the type of genius to have every little detail or gag or sequence preplanned in his head. His scenes and narratives developed from a process of improvisation. Scripts were a non-item. Whole scenes were described with a single sentence, such as “Charlie in jail,” and on the set, Chaplin and his troupe of performers would work out the scene. His genius was bringing these improvised scenes together into a cohesive story, but more than that, making his story as touching and joyful as they often were. The film’s last scene of the Tramp and the Gamine walking into the distance is bittersweet. Not merely because this was the sole instance of Chaplin ending a picture with the Tramp accompanied by a friend, but because it was the Tramp’s last appearance altogether. Modern Times was Chaplin’s last brilliant foray into that singular craft that made him a great artist: a pantomime. From then on, his pictures would be no less endearing or brilliantly conceived, but not the classic or iconographic (or soundless) Charlie that made him legendary.

Bibliography:

Chaplin, Charles. My Autobiography. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

Okuda, Ted; Maska, David. Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp. iUniverse, 2005.

Robinson, David. Chaplin: His Life and Art. McGraw-Hill, second edition, 2001.

Schickel, Richard. The Essential Chaplin: Perspectives on the Life and Art of the Great Comedian. I.R. Dee, 2006.

Vance, Jeffrey. Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema. Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review