The Definitives

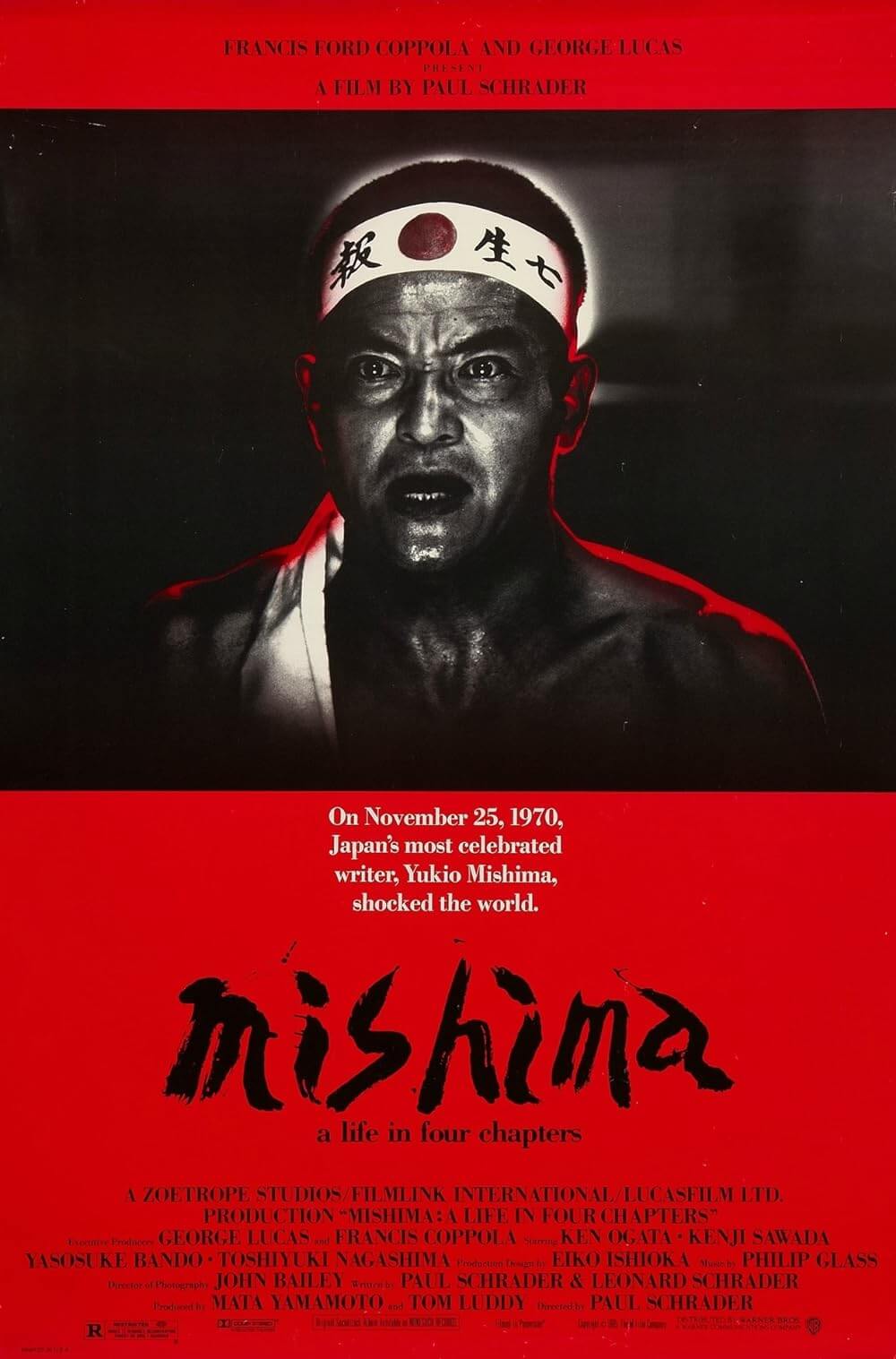

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Yukio Mishima wrote, “Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.” After a life of artistic creation through performance, photography, novels, filmmaking, and poetry, Mishima committed ritual suicide by seppuku on November 25, 1970, when his attempts to reinstate the Emperor through a political coup d’état failed. But Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, written and beautifully directed by Paul Schrader, is not a picture about embattled Japanese postwar ideologies or even a significant moment in Japanese politics. The film explores Mishima’s biography and artistic works to understand how he sought to transform his life into a poem, and in doing so, Schrader avoids the typical format of most cinematic biopics. Rather, the film contains elements of Mishima’s life interwoven with three brief adaptations of his writings. Though, the film’s thematic integrity lies in Schrader’s identification with his subject’s worldview. He recognizes Mishima’s life-poem, and he uses a blend of reality and written word to reveal how Mishima’s suicidal act, and further, his entire life, was a performative work of art contemplating the relationship between beauty, death, and artistic creation. With his 1985 film, he translates Mishima’s story into an original motion picture in which he demonstrates, with theatricality and operatic grandeur, how Mishima’s life and death were driven by performance.

Schrader’s film adopts a layered structure to serve a formally dense, intellectual dissection of its subject matter. The film is divided into four chapters, with each chapter (Beauty, Art, Action, Harmony of Pen and Sword) relaying three elements: black and white flashbacks to Mishima’s past, color scenes from the final day of his life, and vivid passages adapted from his written works. More specifically, the film attempts to reconcile or find a balance between Mishima’s physical life and artistic expression. Schrader’s evident understanding of the controversial figure relates to his own biographical history and psychological preoccupations. As such, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters takes more risks than any Paul Schrader film by embracing the raw, complex, and often sometimes inconsistent characters through a lavish treatment. The film challenges its cultures, both the Japanese culture and setting in which it was made and the largely Western audiences that screen it. The Japanese remain unsure about what to make of Yukio Mishima’s life; it’s a series of irreconcilable contradictions, narcissism, right-wing politics, sexual liberalism, and ceremonial performance. Mishima believed the fear, anxiety, and uncertainty of life was unbearably resistant to answers, and the constant riddle of existence could only be met by creating one’s own reality. Schrader’s film embraces, identifies with, and even admires Mishima’s extreme devotion to a world of his own making.

Yukio Mishima was born in 1925 to a family of samurai ancestry, and as a child, he demonstrated his literary aptitude while living with his strict, elitist grandmother. A frail young man, he was not accepted into the Japanese army; instead, he published his first book in 1948 and entered a prolific writing career. At the time of his death, his body of work consisted of thirty-five novels, twenty-five plays, two hundred short stories, and eight volumes of essays, while also being nominated for a Nobel Prize. Mishima was a Renaissance man and intellectual who was both self-aware and self-destructive. Although he married Yoko Sugiyama in 1958 and had two children, he remained somewhat openly gay. Meanwhile, his artistic prowess extended across various media, including occasional photography and filmmaking, and his narcissism and sexual ambivalence emerged in his life and art. In the 1960s, he became interested in bodybuilding and sword fighting. He believed his body was a metaphor for Japan; it was weak, and he would make it stronger by adhering to samurai ideals. Japan needed strengthening too, he believed, and so he formed his own army, called the Tatenokai (Shield Society), which declared themselves the protectors of the Emperor. Ultimately, they wanted to restore power to the Emperor. Mishima’s final attempt to exact his influence on Japan in 1970 found him in Tokyo’s military headquarters, accompanied by four devoted Tatenokai soldiers who tied up the commander as Mishima tried to convince Japan’s army of his ideas. When his plans failed, Mishima committed seppuku, and a chosen second decapitated him according to the ritual.

Schrader believes that everything about Yukio Mishima belonged to his performative existence, a life-styled art project that extended from his earliest attempts at photography to his dark novels, and to his performance in the military, including the Tatenokai and, ultimately, his suicide. Mishima’s only film, the half-hour Patriotism or The Rite of Love and Death (1966), follows a disillusioned soldier who commits ritual suicide on a traditional Noh theater stage, exploring the artistic and ideological determination of the act. Suicidal impulses and the artistic process are inextricably linked for Mishima, as one’s desire, and final failure, to improve upon or make changes to the world become unbearable. Richard Jordan’s character in Schrader’s first original screenplay, The Yakuza (1974), remarked, “When an American cracks up, he opens up the window and shoots up a bunch of strangers. When a Japanese cracks up, he closes the window and kills himself.” Mishima could have easily lashed out at the world that failed to bend to his needs; instead, he moved inward and acted, subjecting the world to a reality of his own design. The entirety of his life became a stage on which he acted out a role, the final act of which remains a swan song that cannot be easily explained. His final art-statement on November 25, 1970, carried out with formal precision, was an act of self-sacrifice to the notion of artistic purity.

Schrader first learned about Mishima in the 1970s from his brother, who was in Japan at the time of the suicide. Leonard Schrader taught in, and even explored the Yakuza underworld of, Japan’s Kansai region, writing back to his brother Paul with stories of Yukio Mishima. Over the years, the writer-director was drawn to various self-destructive personalities and wrote unfilmed biographies of Hank Williams and George Gershwin, and Mishima followed in that same trajectory of the despairing artist. But Mishima was something altogether different—a rich and mesmerizing subject with a deep fantasy life, an innately dramatic life story, and vivid writings that were profound in their potential for cinematic translation. Above all, Mishima had a philosophy that Schrader could identify with and decipher for his audience better than perhaps anyone else. The Schrader brothers collaborated on the resulting screenplay, drawing heavily from Mishima’s autobiographical and fictional work, and using biographies on Mishima as well. Chieko, Leonard’s wife, adapted the Japanese script.

Coming from a strict upbringing in the Calvinist Christian Reformed Church in the Dutch community of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Schrader was implanted with an initial weariness against “worldly amusements,” including cinema. Famously, Schrader admitted that he didn’t see his first film until his late teens, and The Absent-Minded Professor (1941) hardly swayed him toward the medium. It was not until he became interested in film at Calvin College, where he originally planned to enroll as a minister, that he further explored cinema. He wrote about film for the college’s newspaper and organized the resident film club. During a summer studying film at New York’s Columbia University, the seed was planted for Schrader to become a pupil of Pauline Kael, who encouraged him to apply to UCLA’s film program. There, as a grad student, he completed his Master’s thesis, the 1971 book Transcendental Style in Film, and found himself drawn to films with an intellectual purpose—films that were tools to express a worldview rather than nostalgia. At the same time, he wrote film criticism for the publications L.A. Free Press and Cinema, and he was drawn to challenging films whose meanings remained elusive, and he was fired for writing a negative review about the obviousness of Easy Rider (1969). In the coming years, he started writing screenplays and became a fixture in the New Hollywood of the 1970s, collaborating with Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, and Sydney Pollack before writing and directing his first feature, Blue Collar, in 1978.

Given Schrader’s background, Yukio Mishima might seem like an odd choice of subject matter for his fifth feature film. But throughout his career, he continued to write characters prone to the philosophical, psychological, and sexual confusion that is resolved through purification and redemption, often by physical violence or self-destructive behavior. Additionally, Japanese culture had a distinct and familiar appeal to Schrader. With its precise, regimented, and clean aesthetics, Japan presented a moral certainty within its culture, complete with an expectation of strict adherence to social and artistic decorum. That sort of regimentation followed Schrader from his Calvinist upbringing. “It’s not unusual for a person to flee one prison only to find that same prison in another place,” he told interviewer Kevin Jackson. He explained further, “If I’m going to do a film about my own death-wishes, my own homo-erotic, narcissistic feelings, my own over-calculation of life and my own inability to feel, well, here’s a man who has repeatedly stated those identical problems.” Schrader’s films up to and after Mishima often contain characters who lack an understanding of how they feel, yet they transform their bodies as an act of self-discovery, as Mishima does. His script for Taxi Driver (1976) features Travis Bickle working to get his mind right and reshape his body (“From now on will be total organization. Every muscle must be tight.”). Or watch Julian in American Gigolo (1980) lay out his evening’s costume with organized and color-coordinated apparel, constructing his identity through fashion as if disguising his emotional resistance. Even the monsters in Cat People (1982) undergo a transformation that acts as a kind of emergence of the hidden Self.

To begin turning the subject into a film, Schrader pleaded with Mishima’s widow, Yoko Sugiyama, to grant him the rights to Mishima’s body of work, but she forbade Schrader from adapting any elements of her late husband’s one blatantly homosexual novel, Forbidden Colors, which limited the director’s ability to explore Mishima’s sexual ambivalence—at least through Mishima’s fiction. Even so, certain biographical details and Kyoko’s House contained much of what Schrader sought to accomplish (note a scene where the adolescent Mishima touches himself to a painting of the martyr St. Sebastian’s death by the arrows of Roman emperor Diocletian). The process of acquiring the rights took several years. To finance the film, Schrader acquired half of his budget from Japanese producer Mata Yamamoto, an investor from Fuji Television, and a portion from Toho-Towa Film Corporation—with the stipulation that he never reveal his sources, as Mishima was considered too controversial a subject to adapt. The other half of the financing came from Warner Bros., who were convinced by producers George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, and their companies, Lucasfilm and Zoetrope Studios. Schrader attributed his ease in securing the nearly $6 million budget to his belief that the investors didn’t think the unlikely production would ever happen. But after Mishima’s widow signed over the rights to her husband’s work, and then unsuccessfully tried to back out of their deal, production was underway. Knowing the film would likely fail to recoup its investment, Schrader resolved that “The only criterion I could hold the film up to was that of excellence.”

Filmed in Japan with an entirely Japanese cast and mostly Japanese crew, Schrader’s film took him in a direction other than that of his New Hollywood contemporaries. His producers and financiers on the film, Lucas and Coppola, had struck gold with the mainstream with their Star Wars and The Godfather films. Schrader’s frequent collaborator Martin Scorsese had just made his first comedy (The King of Comedy, 1982), however unconventional it would become. But Schrader took American art filmmaking on another course altogether. Formally, he employed an expressive use of set design and costume, structural complexity, a bold use of both color and black-and-white—all within the ambitions of high art, and the thematic heft to support it. He tells a story about a Japanese figure who remains far from a household name to Western audiences and, furthermore, avoids Westernizing the subject matter by inserting English-language dialogue. Other film biographies, such as Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), appropriated its Indian subject by casting an English actor in the lead role. Japanese performer Ken Ogata plays Yukio Mishima and speaks only his local tongue. Schrader also avoids using an English-speaking entry point character and instead presents all dialogue in English subtitles; even the voiceover is read by Ogata (although, in an alternate version of the film, Roy Scheider delivers the voiceover). Schrader’s approach immerses the viewer in Mishima’s frame of mind to better understand him; any other method would place us at a distance and, further, represent an artistic compromise.

The subject matter, as it was becoming evident in Schrader’s filmography, would become the director’s best kind of film: the biography. In addition to his unfilmed biographies about Williams and Gershwin—scripts that, similar to Mishima, adopted a structure with representative chapters from the subjects’ lives—he wrote Raging Bull, the life story of Jake LaMotta, for his friend Scorsese in 1980. He teamed with Scorsese again on The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988, the same year he directed Patty Hearst, about the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst who was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army. Later, he wrote and directed Auto Focus (2002), about the sexual addiction of TV star Bob Crane. Biographies tempered Schrader’s more untethered instincts in his ambition to expose a sense of himself in his subjects. Rather than adopt a traditional narrative trajectory for Mishima, a table of contents appears in the film’s opening shot, preparing audiences for its unconventional structure. But appreciating Schrader’s originality and thoughtful structure becomes easy when comparing the result to traditional birth-life-death biopics. He treated his structure as his subject treated life, like a work of fiction. Schrader remarked, “He has all the power of fiction, in fact he is a fictional creature because he is a character created by a great writer.”

As described, Mishima has been divided into three sections within each of the first three chapters. The film opens with the chapter Beauty, in which Schrader explores the story Temple of the Golden Pavilion as a parallel to Mishima’s childhood infirmity, his inability to enlist in the army, and his fear of beauty and sexuality. The first moments in this chapter adopt elements from Transcendental Style in Film, which suggest that the “commonplaces of everyday living” are eventually shown in a “disunity between man and his environment which culminates in a decisive action.” Of course, Schrader’s thesis in his book ultimately argues for the opposite approach that he takes in Mishima; he argues for a reduction of sensory stimuli to create, over time, a yearning to discover meaning. Mishima is far more animated and readable, outrageous even, complete with stark contrasts of color and harsh cuts. Color scenes in the first chapter show Mishima on the morning of November 25. He shaves, drinks coffee, and reads the paper like any other day. The mood shifts when he dons his Tatenokai uniform and looks in the mirror. In an abrupt series of cuts, his sees himself in a Noh theater mask, a kendo mask, and a pilot’s helmet—all black-and-white images that reflect the many identities of Mishima. Back in color, he gathers two antique samurai swords, a katana and wakizashi, and leaves the house on his way to the headquarters of the Japanese army where, after failing to sway anyone to his plan, he will kill himself.

As Mishima departs his house, the shot spies a young child in a window; this is the younger version of Mishima, watching himself from the past. The chapter switches to black-and-white, and Ogata’s voice narrates scenes from Mishima’s childhood. Living with his traditionalist, aristocratic grandmother because he’s a “delicate flower,” Mishima first experiences the theater, where he spies an Onnagata—a traditional Japanese actor performing as a female character—and he becomes entranced by the notion of a theatricality that “turns men into women.” As a young adult, he is registered as unfit for military service due to tuberculosis, an illness he exaggerates out of his fear of death. In correspondence with these biographical elements, Schrader intercuts segments from Temple of the Golden Pavilion, a story that follows temple acolyte Mizoguchi (Yasosuke Bando), whose chronic stuttering in the presence of beauty results from his fear to confront its “eternity.” Mizoguchi trembles, frozen in fear and awe in the face of the Golden Pavilion, or even during his first sexual encounter. The character, and thus Mishima, see beauty as a sublime, horrible, and awesome thing that is internal, before the body, and must be “set free”—a reasoning that leads Mizoguchi to set the Pavilion ablaze.

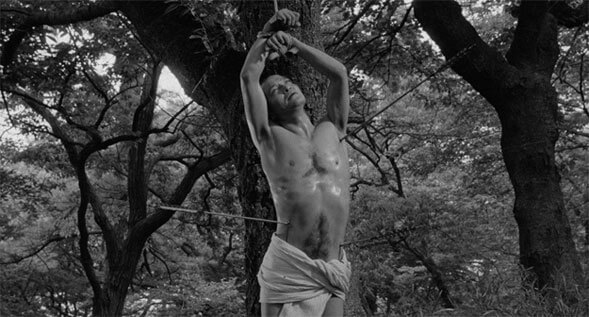

The second chapter, Art, considers Mishima’s relationship between artistic expression and his body. On November 25, he rides in a car with four of his Tatenokai soldiers toward Japan’s army headquarters, and on the way, he sees a bookstore window filled with his face. The scene transitions to black-and-white, with Mishima as a young author who resolves that artistic expression is achieved with more than just words. Given his keen sense of aesthetics, he hates the way he looks. He begins to recognize that life is a performance through self-denial and social conformity—people must construct their mask to the world. He realizes this process can be a form of artistic creation. His homosexuality, for instance, requires, due to social pressure, that he hide himself and forge a new identity, which is undoubtedly why Schrader resists putting Mishima’s wife and two children onscreen. Mishima visits Greece and, confronted by Grecian philosophy and art, he learns that being beautiful is also an artistic expression. He resolves to reshape his body into a work of art through body-building, so “my whole body could be my face.” Schrader also incorporates scenes from Mishima’s book Kyoko’s House into the second chapter, in which the young Osamu (Kenji Sawada) sells his body to the loan shark Kiyomi (Reisen Lee) to save his mother’s restaurant from debt. Osamu becomes Kiyomi’s love slave at first, until their relationship turns into sadomasochism. “Your skin is so beautiful,” she tells Osamu after slicing his flesh, “I just had to cut it.” Their romance becomes one of pain and pleasure, beauty and destruction, a sense of purpose and existence through annihilation, culminating with Kiyomi preparing to bring Osamu to a blissful death. It is this satisfaction through self-regimentation that drives Mishima to the discipline of the bushido, the code of the samurai.

In Action, the third chapter, Mishima and his men approach their objective on November 25, while, in black-and-white flashbacks, Schrader addresses Mishima’s adoption of the samurai code. Aesthetics spread further into life as Mishima idealizes the sacrificial existence of the samurai, its youth and beauty. “The average age for a man in the Bronze Age was 18, in the Roman era, 22,” he observes. “Heaven must have been beautiful then. Today it must look dreadful. When a man reaches forty, he has no chance to die beautifully.” Such extreme vanity saturates Mishima’s unpopular political exterior, as he professes a desire to destroy capitalism in Japan and restore power to the Emperor, thus restoring the tradition of the samurai. Schrader shows the formation of the Tatenokai, their training regimen, their blood pact, and the mystified reactions of the public. But these ideas form in Mishima in service of his devotion to the samurai code as it relates to the body, not as a political ideology. At the same time, Schrader makes associations to Mishima’s story Runaway Horses, about Isao (Toshiyuki Nagashima), a 1930s kendo champion who believes “wooden swords have no real power.” Isao hopes to organize an assassination of capitalist leaders in Japan and then commit seppuku on a cliffside at sunrise, but police break up his rebel cell, and he proceeds alone to kill a capitalist figurehead. Afterward, on the cliff where Isao awaits the sunrise to perform ritual suicide, the act is interrupted by “Cut!” Schrader brusquely transitions back to black-and-white, where, in one of the film’s many visual bridges, Mishima shoots Patriotism or The Rite of Love and Death, and his attention to detail on the short film’s set suggests the artist glorifies seppuku, just as Isao does.

The final transition into the fourth chapter, Harmony of Pen and Sword, is more abrupt. At the end of chapter three, Isao plunges his wakizashi into his stomach, but before the blade makes contact, the shot finds Mishima and his soldiers in their car, arriving at their destination on the Tokyo military base. Chapter four takes place almost entirely on November 25, with Schrader shooting in a style influenced by Costa-Gavras’ handheld vérité camerawork and sharply edited compositions. Mishima and his accompaniment take the base’s general hostage and barricade themselves inside an office. Mishima steps out onto the balcony to speak to a crowd of gathered soldiers, his political rhetoric muffled by the protesting mob and a circling helicopter. Finally, he returns inside, admitting, “I don’t even think they heard me.” Schrader suggests that Mishima adopted a fascistic ideology if only to support a believable motive to carry out his own death; in life, Mishima was apolitical. The Tatenokai and their military action served the singular purpose for Mishima to reconcile his life through art and action in the performance of his death. As scholar Andrew Tracy observes, “It is failure, not victory, which ultimately vindicates the hero, who finally succumbs to the corruption and imperfection of the world.” At the moment Mishima pushes the blade into his stomach, Schrader finally concludes the segments from Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House, and Runaway Horses: Mizoguchi stands in the Golden Pavilion as it burns, Osamu and Kiyomi lie dead on the floor, and Isao disembowels himself on the cliff before the rising sun. Through his suicide, Mishima has finally become one of his creations and achieved an end befitting his artistic ambition.

Throughout the film, Schrader’s use of color, from his specific color choices to when he chooses color over monochromatic scenes, remains significant to understanding Mishima. Schrader uses color to signify acts of performance, meaning, and art, whereas monochromatic scenes contain lifeless biographical information. The black-and-white scenes adopt styles that evoke prewar Japanese masters, a class of filmmaker of which Schrader is an expert. Above all, the black-and-white scenes reflect the static style of Yasujiro Ozu, quite fittingly, as Schrader explored Ozu in Transcendental Style in Film. During the Beauty chapter, scenes inside Mishima’s childhood home are filmed with a camera peering through doorways or down halls, shot from low angles, as in an Ozu film. The black-and-white scenes frequently use long takes and have a pristine Japanese aesthetic behind them, evoking other filmmakers from Kenji Mizoguchi to Mikio Naruse. By contrast, the color scenes veer away from biographical details in Mishima’s life, as color represents his fictional writings. Art and color are inextricably linked, whereas everyday life is a matter of black and white. At first, the scenes from November 25 seem out of place in this dynamic, until the final intercutting of climactic scenes when, through editing, Schrader connects Mishima’s suicide with the burning of the Golden Pavilion, the euphoric and sadomasochistic death of Osamu in Kyoko’s home, and Isao’s suicide. Schrader denies the audience full view of these moments until the film’s last sequence, when he links them, and it becomes evident that Mishima’s suicide is his final work of art.

Along with his use of color and black-and-white photography, gorgeously rendered by cinematographer John Bailey, Schrader juxtaposes flashbacks and actual locations in the November 25 scenes with high-concept set designs for adaptations of Mishima’s written work. To achieve this, he recruited Eiko Ishioka. Schrader had seen Ishioka’s Japanese posters for Apocalypse Now (1979) and her book, Eiko by Eiko, a collection of shopping mall advertising concepts, and felt her mannered style would give each of Mishima’s stories a distinct look. She conceived each novel’s segment with a distinct color coding to help the viewer organize them in their mind: The Temple of the Golden Pavilion appears in metallic golds and green; Kyoko’s House appears in pinks and grays; Runaway Horses uses black and shu, an orange hue used in Japanese temples. The individual set-pieces often appear surrounded by black, empty space, as if placed on a dramatic stage. Having never designed film sets, Ishioka enlisted help from Kazuo Takenaka, a veteran set designer who decorated the biographical scenes throughout the film. Due to her exceptional work on Mishima, Ishioka would become a sought-after designer in Hollywood. She later conceived many of the visual splendors from Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and Tarsem’s The Fall (2006).

Schrader achieves the film’s momentous culmination by creating parallels between the biographical elements of his film and the chosen texts, but composer Philip Glass connects these scenes through his resounding score, his music reverberating through them. Glass had written magnificent operas about the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten, Mahatma Gandhi, and Albert Einstein, but never a film score. Schrader commissioned him to carry out a similarly operatic style for his score to Mishima, and Glass composed the score without seeing the film. Schrader then cut the recorded music and placed it where he saw fit, at which point Glass took Schrader’s edits and recomposed the final film score. The winding melodies and circular nature of Glass’ music creates an aural metaphor, allowing the viewer to both feel and intellectualize the various ongoing narratives in the film. The score gives way to bold rushes of exuberance, particularly in the final sequence that connects through montage the revelatory fates of Mishima and his characters, by building to a familiar zenith repeated throughout the film, much to the audience’s exhilaration.

But critics and audiences were not so exhilarated. Curiously, Japanese audiences resisted Schrader’s film. The director perceived a “cultural discomfort” about Mishima among Japanese historians and cultural studies scholars who are unable to make sense of his life, suicide, and artistic project. After World War II, Japan took pride in setting aside their imperialism to become a capitalistic and democratic society—a Western-centric constitutional monarchy. And yet, despite their fitting in better among major world powers, their great author and artist Yukio Mishima rejected their future, embraced a symbol of their tragic past by honoring a samurai’s devotion to the Emperor, and then disemboweled himself before the world. Schrader also attributed the Japanese response to a Westerner taking on a decidedly Far East subject and appropriating it—after all, if Japanese commentators cannot make sense of Mishima, how could a Westerner? To this day, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters has never had an official release in Japan. Although the film won an award for “Best Artistic Contribution” at the Cannes Film Festival and received glowing reviews from Sight and Sound, critics in the National Review, the New Republic, and Art in America were less enthusiastic. Vincent Canby in the New York Times wrote the film wasn’t “likely to make much sense to anyone who hasn’t read some of the novels.” To be sure, Mishima improves after reading the author’s texts and knowing about his life in advance, but the uninitiated will derive untold joys from the sumptuousness of Schrader’s filmmaking and his unscrambling of Mishima’s artistic vision.

Mishima allowed Schrader to once again explore his own death drive, the feeling that impelled him to write Taxi Driver in a matter of days. Schrader’s suicidal neuroses were driven by his self-imposed isolation, obsessions, and violence. To complete the screenplay for Scorsese’s film, he placed a loaded gun nearby to compel himself to either finish the script or end his life. This sort of live-or-die-by-art perspective has remained with Schrader throughout his career, although he believed Mishima resolved his own preoccupation with and temptation to end his life. “The more I wrote,” Mishima says in the film, “the more I realized that mere words were not enough. So I found another form of expression.” For Schrader, exploring his temptations and suicidal impulses by making the film served as a form of therapy. “Mishima represented the end of my interest in suicidal glory,” he said later, calling it the “end of what I wanted to say about it.” Mishima demonstrates the finality of living art. And from the rush of how Schrader filmed the connections between art, bliss, and death, he achieved a personal catharsis. Afterward, fewer self-destructive characters appeared in his films. Nevertheless, self-destruction can be found in the themes of Schrader’s later films and screenplays such as Affliction (1997), Bringing Out the Dead (1999), and First Reformed (2018).

Yukio Mishima was an artist who may have savored little about the every day, relishing his secret life instead through the carefully constructed façade he presented to the world. But his devotion to his performative being transcends how cultures—Japanese, Western, or otherwise— think about and view art, while also reflecting the broken and disastrously isolated person behind the performance. Through a myriad of contexts ranging from the past, present, fantasy, and fiction, Paul Schrader made a rousing and strikingly beautiful film about Mishima. He avoids judging or taking issue with how Mishima chose to use his artistic gifts or his penetrating, intimate observations about existence. Rather than comment on the tragedy of Mishima’s death or the waste of his talent, Schrader attempts to understand Mishima’s artistic project from his uniquely similar subjective perspective. The themes of purification and understanding through violence, sexual denial, and artistic expression in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters are inherently cinematic, and Schrader realizes them in a biography unlike any before or since. In a bastion of artistry and intellectual seriousness, Schrader engages the problem of Mishima and provides an answer through extravagant, thoughtful filmmaking.

Bibliography:

Jackson, Kevin, editor. Schrader on Schrader. Revised Edition. Faber and Faber Limited, 2004.

Kouvaros, George. Paul Schrader. University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Schrader, Paul. Transcendental Style in Film. Revised Edition. University of California Press, 2018.

—. “Dialogue on Film.” American Film, vol. 14, no. 9, July/Aug. 1989, pp. 16-21.

Tracy, Andrew. “A Problem Like Mishima.” Cinema Scope, no. 36, Fall 2008, pp. 32-35.

Wilson, John Howard. “Sources for a Neglected Masterpiece: Paul Schrader’s Mishima.” Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 3, 1997, pp. 265-283.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review