The Definitives

Minority Report (2002)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

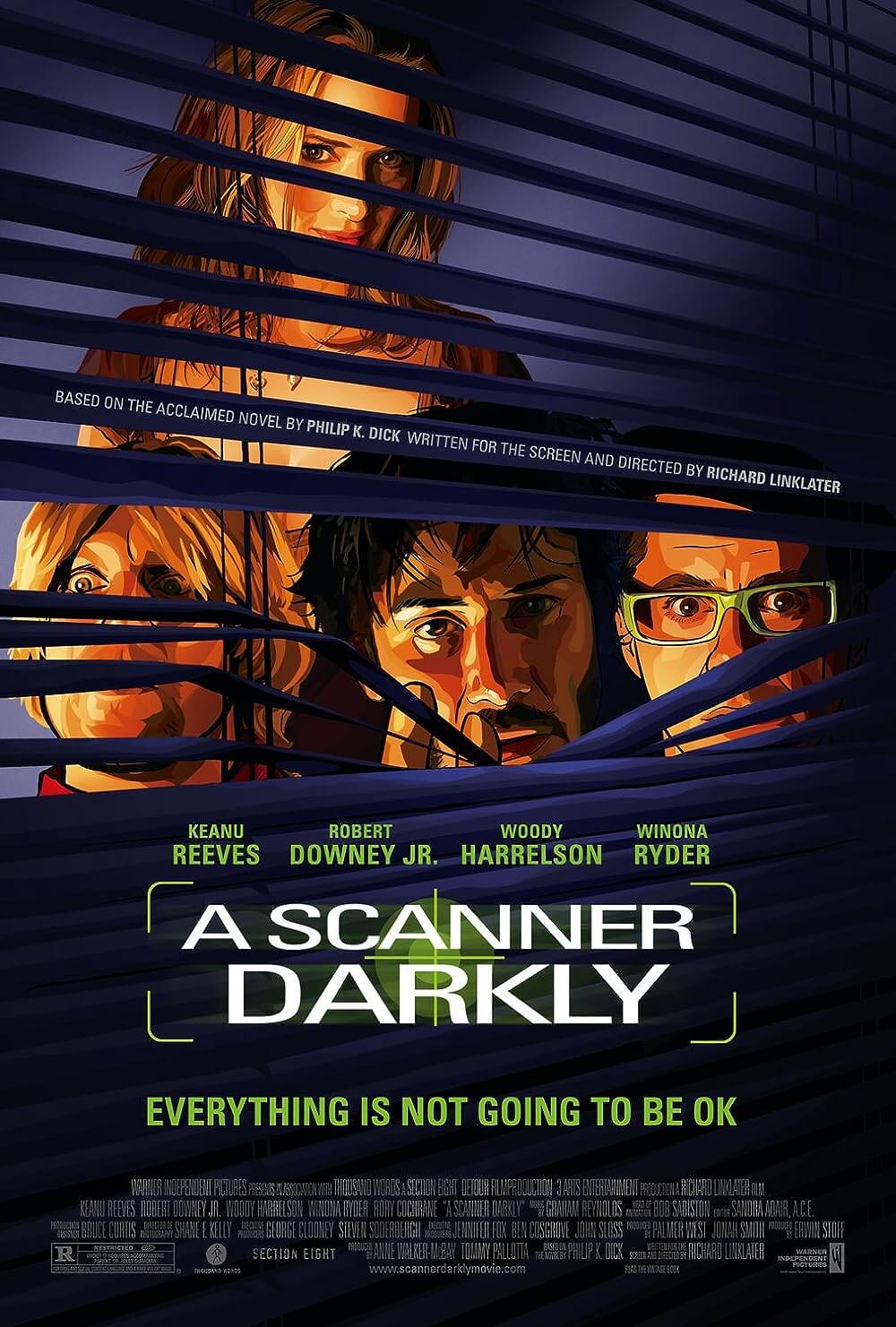

Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report realizes the full potential of author Philip K. Dick’s science-fiction worldview, a perspective filled with dangerous technology, feverish paranoia, and metaphysical philosophies. Spielberg’s complicated, wonderfully stylized approach uses Dick’s 1956 short story of the same name as a launching pad. While it captures the author’s vision of an imperfect future and the perilous reality that dwells under the alluring surface of futurism, the picture also stands as Spielberg’s most extraordinary exhibit of pure filmmaking. Minority Report augments and expands on the source material, concentrating Dick’s obsessions about the potential dangers of technology and the author’s ongoing existential battle between free will and determinism, especially in regard to the manipulation of time, such as time travel or precognition. Over more than forty novels and several short story collections, Dick’s work permeates a sense of fascination and suspicion toward the future. The fascinating prospect of new technologies, exploration of new frontiers, and humanity’s evolutionary progression of extra-sensory perceptions consume his output. And yet, he always investigates their inevitable downfalls. His stories feature characters hindered by supposed advancements, thrown into the central conflict by a set of circumstances put into motion by unsound developments. In that tradition, Spielberg’s film is a nonstop chase, at once a thriller of epic escapist and intellectual bravado. It amalgamates Hitchcockian suspense, elements of film noir, and Dick’s vision of the future, three of the most distinctive and inventive of all storytelling styles, into a single source, resulting in a masterful triumph from a masterful filmmaker.

Set in the near-future, Minority Report introduces the concept of Precrime, Washington D.C.’s exploration into a revolutionary form of law enforcement. Founded by Lamar Burgess (Max Von Sydow) and headed by Chief John Anderton (Tom Cruise), Precrime utilizes the “gifts” of the Precogs, three clairvoyants who have given up their freedom to support the cause of detecting crimes before they occur. The Precogs’ foreseen visions are analyzed by the Precrime unit and verified by a council of judges; a positive mark is identified, and suddenly officers race to prevent a crime from taking place. Impending perpetrators are caught and then booked before ever committing an offense. When the film opens, there hasn’t been a murder in the District of Columbia for six years; the existence of Precrime alone virtually eliminates the consideration of murder, so only crimes of passion remain. Though dedicated to the ideology of Precrime, Anderton’s personal life is in shambles. Long ago, his young son disappeared at a public pool; now a divorcé, he whiffs neural drugs to escape the guilt and painful memories of his former life. On the job, however, he remains professional and composed. In the opening scenes, Justice Department representative Danny Witwer (Colin Farrell) enters the Precrime offices to audit the program for national expansion and meets Anderton, who jealously protects the system he helped build. Witwer’s insistence that a human component will ultimately threaten the countrywide growth of Precrime quickly proves true after the Precogs predict that Anderton will commit a murder. Anderton has no plans to kill anyone, nor does he recognize the foretold victim, someone named Leo Crow. But knowing the efficient and absolute manner in which Precrime officers detain their would-be perps, Anderton has no choice but to run and attempt to prove his innocence on the lam.

Established within these first scenes are all the elements of a wrong-man thriller, drawn from the institution of Alfred Hitchcock’s cinema. Titles like The 39 Steps and Saboteur begin with the false charge of murder, the yarn unraveling as the protagonist does the impossible to prove their innocence. These are spellbinding stories that contain an immediate suspense given the nature of the plot. Spielberg takes every advantage of that, employing Hitchcockian tropes in the film’s high-tech setting. While following Anderton’s flight from justice, the director uses the chase to explore the film’s ultramodern environment, showcasing a range of technology and equipment, but never slowing his pace to artificially linger on the background details more than the immediate wrong-man scenario. Hitchcock did the same, making his environments entirely functional within their scenes, though distinctive in their selection. North by Northwest, for example, uses Mount Rushmore, an emblematic and immediately identifiable landmark for its rousing finale, the characters dodging bullets and hanging on for dear life by the edges of the monument’s massive sculpted faces. And yet, the heads of those former presidents are never more interesting than Cary Grant. Minority Report‘s screenplay, written by Scott Frank and Jon Coen, scatters an array of multihued characters into the futuristic milieu, the most diverse of them appropriately being John Anderton. Peter Stomare plays a vengeful doctor with a nasty cold; Tim Blake Nelson is the Precrime prison’s wheelchair-bound containment sentry; Daniel London as the clingy babysitter of the Precogs in their floating nutrient pool; Lois Smith is the pessimistic, sharp-witted mother of Precrime. Cruise, however, renders the performance of his career as Anderton. His intensity and dimensionality make the story not merely one of watching as special-effects instill marvel, but one fully grounded in the motivation of the character, the importance of the chase, the pain of his tragic background, and his pursuit of answers to a crucial mystery.

Established within these first scenes are all the elements of a wrong-man thriller, drawn from the institution of Alfred Hitchcock’s cinema. Titles like The 39 Steps and Saboteur begin with the false charge of murder, the yarn unraveling as the protagonist does the impossible to prove their innocence. These are spellbinding stories that contain an immediate suspense given the nature of the plot. Spielberg takes every advantage of that, employing Hitchcockian tropes in the film’s high-tech setting. While following Anderton’s flight from justice, the director uses the chase to explore the film’s ultramodern environment, showcasing a range of technology and equipment, but never slowing his pace to artificially linger on the background details more than the immediate wrong-man scenario. Hitchcock did the same, making his environments entirely functional within their scenes, though distinctive in their selection. North by Northwest, for example, uses Mount Rushmore, an emblematic and immediately identifiable landmark for its rousing finale, the characters dodging bullets and hanging on for dear life by the edges of the monument’s massive sculpted faces. And yet, the heads of those former presidents are never more interesting than Cary Grant. Minority Report‘s screenplay, written by Scott Frank and Jon Coen, scatters an array of multihued characters into the futuristic milieu, the most diverse of them appropriately being John Anderton. Peter Stomare plays a vengeful doctor with a nasty cold; Tim Blake Nelson is the Precrime prison’s wheelchair-bound containment sentry; Daniel London as the clingy babysitter of the Precogs in their floating nutrient pool; Lois Smith is the pessimistic, sharp-witted mother of Precrime. Cruise, however, renders the performance of his career as Anderton. His intensity and dimensionality make the story not merely one of watching as special-effects instill marvel, but one fully grounded in the motivation of the character, the importance of the chase, the pain of his tragic background, and his pursuit of answers to a crucial mystery.

When Anderton decides to flee, a series of events perfectly ingrained into the future world of the film build to a matchless chase sequence, compiling twenty or so of the most exhilarating minutes in all of cinema. Inside his magnetically propelled car which rides on automated tracks, Anderton speaks to Burgess in a frenzied attempt to determine why he would murder this man named Leo Crow. As Precrime takes control of Anderton’s vehicle remotely, he carhops on a vertical highway and eventually makes his way to the subway. Eye scanners that track oncoming passengers via retinal charting help Precrime officers meet Anderton on the platform at the next stop; on jetpacks they pursue him into an alleyway where, when cornered, Anderton attacks, zapping his former colleagues with their own “sick sticks.” After commandeering a jetpack for himself, he flies through an apartment complex, escaping into an industrial district. The chase ends in an automated car factory, amid mechanical parts flashing sparks and robot assembly lines busying themselves. The officers on Anderton’s tail wield energy force “concussion guns,” blasting boxes and each other without harming surfaces. Witwer arrives on scene and he and Anderton engage in fisticuffs. Our hero drops from a moving platform onto the assembly line, into the framework of an unfinished vehicle. Automaton arms install pieces of the vehicle around him, Anderton barely evading part after part during the car’s assembly. His pursuers watch from a distance as the vehicle comes together, their perpetrator nowhere to be seen, possibly crushed inside the car being built around him. The car moves off the factory line, its construction finished; then Anderton sits up in the driver’s seat, unharmed. In one motion from the assembly line to speeding away to freedom, Anderton’s escape is complete.

Spielberg envisaged the car factory sequence from a concept originally envisioned by Hitchcock for North by Northwest. The Master of Suspense wanted Cary Grant’s character, Roger O. Thornhill, to find himself in a Detroit automobile factory. As Thornhill walked and talked with an informant, the audience would have witnessed a car in the background being built on the factory line through a single tracking shot. Alas, Hitchcock and his writer Ernest Lehman could not conceive a reason to place Thornhill in Detroit, so the proposal was scrapped. Spielberg adapted it for Minority Report, using a piece of unproduced film history to directly acknowledge his picture as an ode to Hitchcockian devices. Another Minority Report scene features Anderton escaping into the rain with an umbrella, a Precog, Agatha (Samantha Morton), guiding him to freedom by forecasting every move he should make to elude his pursuers. As Precrime officers pursue him on a higher level, they look down to see a crowd of pedestrians all with umbrellas and Anderton, umbrella overhead, lost in the throng, the scene a direct parallel of one in Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. But more than a particular scene or two, Minority Report borrows the raw cinematic essence of Hitchcock thrillers—the atmosphere of tension combined with a pitch of pure, joyful entertainment. The momentum, from the nonstop crescendo of thrills throughout to the very public and quickly resolved finale, mirrors that of films like North by Northwest and Saboteur, and a dozen other Hitchcock pictures. The tone is serious while also allowing for humor, and the suspense never loses its potency. Spielberg uses Hitchcockian bird’s eye camera angles, long zooms, and sets his story to a rousing score by John Williams worthy of Bernard Herrmann, without losing his own directorial flourishes. And he accomplishes all this without feeling derivative; indeed, moviegoers not intimately familiar with Hitchcock’s oeuvre will miss the reverence hidden in plain sight onscreen.

Spielberg envisaged the car factory sequence from a concept originally envisioned by Hitchcock for North by Northwest. The Master of Suspense wanted Cary Grant’s character, Roger O. Thornhill, to find himself in a Detroit automobile factory. As Thornhill walked and talked with an informant, the audience would have witnessed a car in the background being built on the factory line through a single tracking shot. Alas, Hitchcock and his writer Ernest Lehman could not conceive a reason to place Thornhill in Detroit, so the proposal was scrapped. Spielberg adapted it for Minority Report, using a piece of unproduced film history to directly acknowledge his picture as an ode to Hitchcockian devices. Another Minority Report scene features Anderton escaping into the rain with an umbrella, a Precog, Agatha (Samantha Morton), guiding him to freedom by forecasting every move he should make to elude his pursuers. As Precrime officers pursue him on a higher level, they look down to see a crowd of pedestrians all with umbrellas and Anderton, umbrella overhead, lost in the throng, the scene a direct parallel of one in Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. But more than a particular scene or two, Minority Report borrows the raw cinematic essence of Hitchcock thrillers—the atmosphere of tension combined with a pitch of pure, joyful entertainment. The momentum, from the nonstop crescendo of thrills throughout to the very public and quickly resolved finale, mirrors that of films like North by Northwest and Saboteur, and a dozen other Hitchcock pictures. The tone is serious while also allowing for humor, and the suspense never loses its potency. Spielberg uses Hitchcockian bird’s eye camera angles, long zooms, and sets his story to a rousing score by John Williams worthy of Bernard Herrmann, without losing his own directorial flourishes. And he accomplishes all this without feeling derivative; indeed, moviegoers not intimately familiar with Hitchcock’s oeuvre will miss the reverence hidden in plain sight onscreen.

What Spielberg does differently than Hitchcock is turn his central plot device, or MacGuffin, into a critical philosophical tool for the entire film, versus the frivolous and pointless item Hitchcock’s MacGuffin usually proves to be. Hitchcock used microfilm or diamonds or cold hard cash, whereas the MacGuffin in Minority Report proves to be the eponymous file saved in the Precog’s brain. The three Precogs (Agatha, Dashiell, and Arthur, named after three writers you may have heard of) work as a hive mind, but the most gifted of them, Agatha, occasionally sees something different than the other two. Agatha’s “minority report” suggests that the Precogs’ vision will not necessarily occur the way they have communally predicted. For the integrity of Precrime, Burgess ordered that these reports be destroyed, though a copy remains stored away in Agatha’s unconscious. When Anderton learns of this, he sets out to find his minority report, if one exists, and expose his probable innocence. But before ever approaching the futuristic megalopolis wherein Precrime and ultimately his innocence reside, he prepares himself. Knowing that no matter how stealthy he may be, retinal scanners will identify him before ever reaching the city, Anderton arranges for an eye transplant in the criminal underground. He enters The Sprawl, a dodgy part of town both dark and enclosed, where Spielberg mutates his thriller with a film noir interlude. Projected on the room’s dank wall is a scene from Samuel Fuller’s gritty noir classic The House of Bamboo (a scene which Spielberg later uses to mirror Witwer’s death), an homage that also nods to the noirish manner of these scenes. A mad doctor performs Anderton’s procedure, leaving his eyes bandaged for a mandatory 12-hour recovery, his only comfort being some rotten chow in the fridge should he get hungry. Shadows fill the room, ceiling fans keep the space active, and neurological drugs pass the time. In the scenes prior to and after this sequence, the film contains a blue-gray sheen. Frequent Spielberg cinematographer Janusz Kaminski over-lights the bright future, bleach-bypassing them in post-production to retain a metallic utopian polish. But in The Sprawl there is only darkness interrupted by high contrast lighting.

Driven into hiding by state-of-the-art policing technologies, Anderton must leave The Sprawl when technology seeks him out. A patrol moves from building to building in search of their fugitive, dropping “spiders” to scout out and scan residents. These self-guided, metallic gizmos scurry into homes for mandatory retinal identification; however, Anderton’s eyes need more time to heal from his surgery. Opening them now could leave him blind, and so he submerges himself in ice water to block the spiders’ infra-red sight. The spiders move from room to room, as Spielberg shows us in a skillful overhead sequence, filmed using an amazing set piece with precise camera movements that capture the residents through broken light panels and shabby ceiling tiles. The robotic hunters locate Anderton, hearing the smallest sound, but they scan only the counterfeit identity he paid for. What absorbing ideas these are for a world of plausible ingenuity. Part of Minority Report’s appeal is reveling in the superior technologies; headhunting spiderbots and magnetic cars and retinal scanners take a foreground role, but production designer Alex McDowell (Fight Club) imparts every scene with something imaginative and new. While many of the wonders therein originated in Philip K. Dick’s body of work, the better part of the film’s futuristic gear was conceived by some of today’s top minds. In 1999, two years prior to filming, Spielberg arranged a conference between fifteen specialists from various scholarly branches to assist in devising a believable, relevant futureworld. Representatives from the fields of architecture, biomedical research, physics, transportation, and modern fiction gave their input and helped boost the environment of the film, lending the configuration behind the film’s distinctive look, while also conceiving those clever details that make the world a believable tomorrow.

Driven into hiding by state-of-the-art policing technologies, Anderton must leave The Sprawl when technology seeks him out. A patrol moves from building to building in search of their fugitive, dropping “spiders” to scout out and scan residents. These self-guided, metallic gizmos scurry into homes for mandatory retinal identification; however, Anderton’s eyes need more time to heal from his surgery. Opening them now could leave him blind, and so he submerges himself in ice water to block the spiders’ infra-red sight. The spiders move from room to room, as Spielberg shows us in a skillful overhead sequence, filmed using an amazing set piece with precise camera movements that capture the residents through broken light panels and shabby ceiling tiles. The robotic hunters locate Anderton, hearing the smallest sound, but they scan only the counterfeit identity he paid for. What absorbing ideas these are for a world of plausible ingenuity. Part of Minority Report’s appeal is reveling in the superior technologies; headhunting spiderbots and magnetic cars and retinal scanners take a foreground role, but production designer Alex McDowell (Fight Club) imparts every scene with something imaginative and new. While many of the wonders therein originated in Philip K. Dick’s body of work, the better part of the film’s futuristic gear was conceived by some of today’s top minds. In 1999, two years prior to filming, Spielberg arranged a conference between fifteen specialists from various scholarly branches to assist in devising a believable, relevant futureworld. Representatives from the fields of architecture, biomedical research, physics, transportation, and modern fiction gave their input and helped boost the environment of the film, lending the configuration behind the film’s distinctive look, while also conceiving those clever details that make the world a believable tomorrow.

Spielberg renders the film’s technology through a seamless blend of computer-generated images and physical creations, being a filmmaker who knows how to craft the fantastical into reality. Be it dinosaurs, wondrous UFOs, or lost biblical artifacts, the director’s ability to make the impossible seem real is unmatched. As a result, Spielberg’s mise-en-scène feels credible, more so than comparable science-fiction settings. The futurist aspects of the film were designed to be integrated with contemporary architecture, as if the environment had been built upon again and again through generations of advancement. The practicality of this filmic world and its believable consumer products have such a tangible sense of possibility that modern scientists have begun building what movie special-effects wizards created for the film. 3-D holograms, with which Anderton views home videos of his wife and son, appeared on CNN during the 2008 presidential election. NEC Corporation unveiled a camera in Japan that detects age and sex, formatting nearby advertisements to fit the photographed audience, similar to the retinal scanners in the film. And a number of companies have used Minority Report as inspiration to make touch-screens (like the iPad) and gestural interfaces (Xbox’s Kinect) a reality, drawing from the scenes where Anderton disassembles the seemingly random images from the Precog vision by tossing them about a clear, free-floating computer console. And when Minority Report isn’t shaping our real-life world, its influence is felt on countless other films, including virtually every subsequent sci-fi effort—Michael Bay’s The Island, Marvel’s Iron Man, J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek, and the list goes on.

The film’s technology is never included superfluously. Each piece makes a comment on the scene or the vast future envisioned within the film, fully embedding them into the moment organically, always in service of the story’s unrelenting momentum. Consider the intrusive advertising, compelled by retinal scanners that read Anderton’s identity and try to sell him everything from beer to cars, or chart when he gets on the subway. Reading the retina, they flash across the eye to capture an identity, logging the information, location, and patterns into a stored database. Shown as a security measure early in the film, the scanner turns into a dangerous trap when Anderton is a fugitive, as the police connect to the scanning database to help find their man. Although the presence of in-film advertisements undoubtedly served needed product placements (most prominently Lexus, Pepsi, and Gap) and therein financing for the $102 million dollar production, the film itself integrates the technology of advertising scans into the thriller scenario, and the presence of the scanners and ads shifts dramatically, transforming into an invasion of privacy and an obstacle Anderton must overcome. Empathizing with the wrong-man hero, the viewer now sees the scanner less as a device to follow shopping habits and more of a tool to retain order. And because of this, Anderton goes to the extreme of transplanting his eyes with that of a non-criminal to escape the scanners’ constant presence. In another of Minority Report influences on modern culture, the seemingly futurist 2002 film predicted the outgrowth of invasive ads in metropolitan centers such as Times Square or downtown Tokyo.

The film’s technology is never included superfluously. Each piece makes a comment on the scene or the vast future envisioned within the film, fully embedding them into the moment organically, always in service of the story’s unrelenting momentum. Consider the intrusive advertising, compelled by retinal scanners that read Anderton’s identity and try to sell him everything from beer to cars, or chart when he gets on the subway. Reading the retina, they flash across the eye to capture an identity, logging the information, location, and patterns into a stored database. Shown as a security measure early in the film, the scanner turns into a dangerous trap when Anderton is a fugitive, as the police connect to the scanning database to help find their man. Although the presence of in-film advertisements undoubtedly served needed product placements (most prominently Lexus, Pepsi, and Gap) and therein financing for the $102 million dollar production, the film itself integrates the technology of advertising scans into the thriller scenario, and the presence of the scanners and ads shifts dramatically, transforming into an invasion of privacy and an obstacle Anderton must overcome. Empathizing with the wrong-man hero, the viewer now sees the scanner less as a device to follow shopping habits and more of a tool to retain order. And because of this, Anderton goes to the extreme of transplanting his eyes with that of a non-criminal to escape the scanners’ constant presence. In another of Minority Report influences on modern culture, the seemingly futurist 2002 film predicted the outgrowth of invasive ads in metropolitan centers such as Times Square or downtown Tokyo.

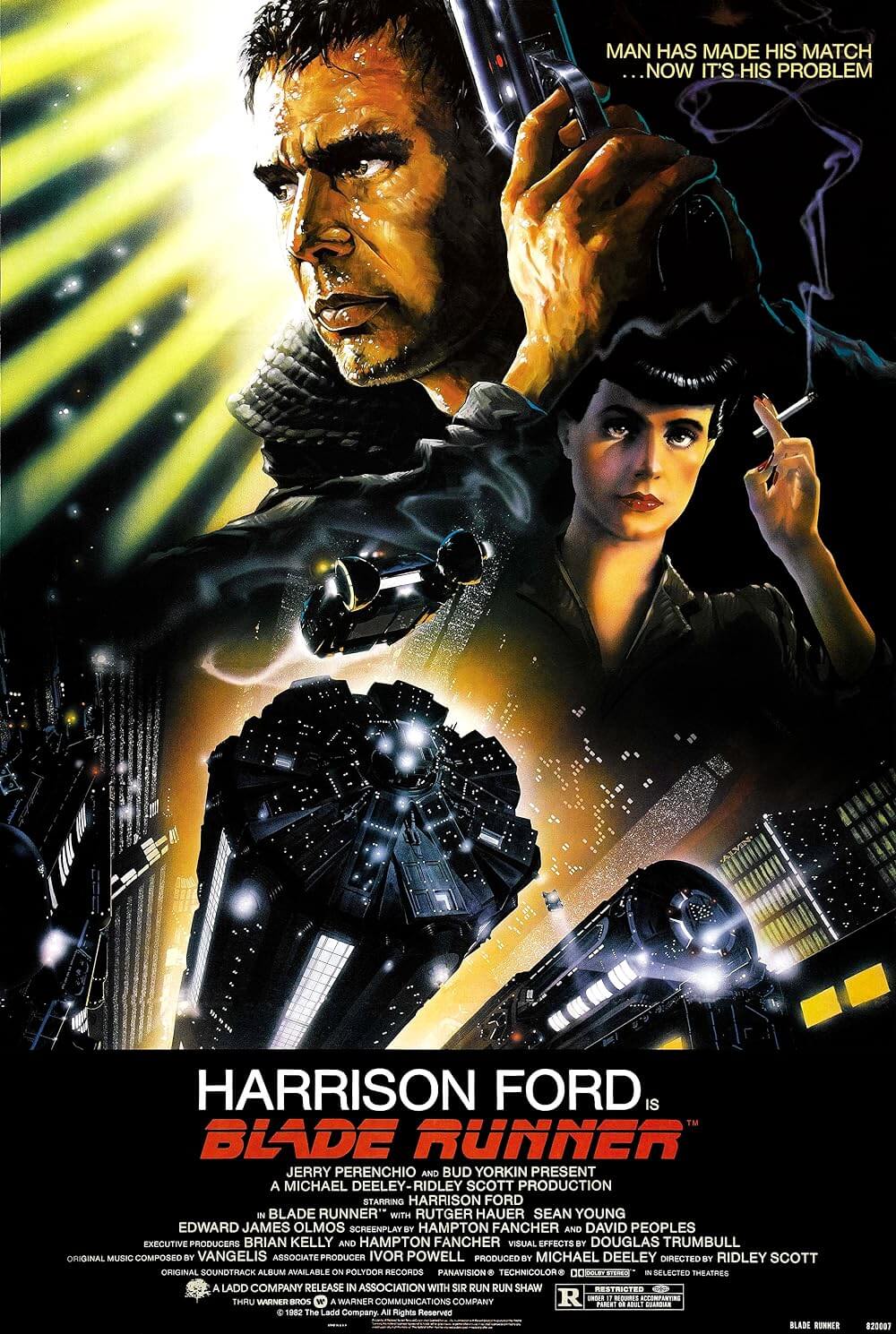

Set aside the suspense of this extended sequence of events, if possible, and instead reflect on what each technological detail tells the audience about the world of Minority Report. The magnetic car suggests this future offers an environmentally friendly solution to transportation, but that the driver has no control over their vehicle should an emergency arise. The eye scanners alert police to dangerous persons on the subway, making one of the most typically dangerous forms of public transportation worry free. Indeed, these conveniences make life easier, but they also grant a near absolute authority to the nonlethal police. The jetpack, Spielberg’s nod to the escapist sci-fi serials of yesteryear, remains the most implausible piece of technology in the film; though Spielberg acknowledges as much when Anderton spins his teammate opponents out of control. The technology reveals the utopia of Minority Report to be a dystopia in disguise. In Blade Runner, another Philip K. Dick adaptation, director Ridley Scott made the decomposition of his future landscape apparent in every frame, the putrefaction of the setting undeniable. Spielberg, conversely, aligns the conditions with the story. In the opening scenes, the District of Columbia gleans from its perfection, its rightness and spectacle soon to be expanded across the country when Precime is approved for national expansion. When Anderton wields technology in his favor, Spielberg treats it as an extraordinary spectacle. But when the hunter becomes the hunted, every tool at his disposal twists into a dangerous villain, frightening and impossible to counteract. Only through Anderton’s desperate humanity can he fight it. A futurology such as Dick’s admires how beneficial technology can be but also weighs the inevitable dehumanizing downfalls.

In the case of Precrime, the question of technology develops into one of Free Will versus Determinism within an entrenched timeline, and using said technology to breach that timeline. Beginning with the Precogs’ prediction that Anderton will commit murder, the indictment sets into motion a chain of events that inevitably leads Anderton to kill his predicted target. So the question remains, would Anderton have killed Leo Crow if the accusation was not made? This is the film’s philosophical paradox through which the McGuffin is rendered all-important; and while raised, the question can garner no correct response outside of creative guesswork. The critique of the would-be utopia is complete when Anderton rescues Agatha to find his minority report; he learns she is not a foreseeing wunderkind, but an accident resulting from her neurological drug-addicted mother, and a prisoner in her position. Atrophied and woozy from the sedatives the technicians keep her on to predict more fluently, Agatha is nearly broken, jaded by the present, and clumsily clinging to her rescuer. She informs Anderton that though he has no minority report, he has a choice; by knowing his future, he can thusly change it by force of will. The structure of Determinism is subject to the unpredictability of Free Will. Regardless of his lacking minority report, Anderton has the self-control not to kill Crow. This choice repeats itself in the finale when Anderton confronts Burgess, the architect of the film’s frame job. The Precogs predict Burgess will kill Anderton, but Burgess chooses differently. The utopian aspects of the future, as well as The Precogs that are all but deified by their followers for the violence they have prevented, are both proven façades within a defective future bent on maintaining an illusion of perfection. In true form for Philip K. Dick, but strangely pessimistic for director Steven Spielberg, the film portrays the crumbling of a utopia through its reliance on its advances. Even if the story ends well for Anderton and the freed Precognitives, the future is nonetheless a bleak one.

In the case of Precrime, the question of technology develops into one of Free Will versus Determinism within an entrenched timeline, and using said technology to breach that timeline. Beginning with the Precogs’ prediction that Anderton will commit murder, the indictment sets into motion a chain of events that inevitably leads Anderton to kill his predicted target. So the question remains, would Anderton have killed Leo Crow if the accusation was not made? This is the film’s philosophical paradox through which the McGuffin is rendered all-important; and while raised, the question can garner no correct response outside of creative guesswork. The critique of the would-be utopia is complete when Anderton rescues Agatha to find his minority report; he learns she is not a foreseeing wunderkind, but an accident resulting from her neurological drug-addicted mother, and a prisoner in her position. Atrophied and woozy from the sedatives the technicians keep her on to predict more fluently, Agatha is nearly broken, jaded by the present, and clumsily clinging to her rescuer. She informs Anderton that though he has no minority report, he has a choice; by knowing his future, he can thusly change it by force of will. The structure of Determinism is subject to the unpredictability of Free Will. Regardless of his lacking minority report, Anderton has the self-control not to kill Crow. This choice repeats itself in the finale when Anderton confronts Burgess, the architect of the film’s frame job. The Precogs predict Burgess will kill Anderton, but Burgess chooses differently. The utopian aspects of the future, as well as The Precogs that are all but deified by their followers for the violence they have prevented, are both proven façades within a defective future bent on maintaining an illusion of perfection. In true form for Philip K. Dick, but strangely pessimistic for director Steven Spielberg, the film portrays the crumbling of a utopia through its reliance on its advances. Even if the story ends well for Anderton and the freed Precognitives, the future is nonetheless a bleak one.

Beyond the genius sewn into the fabric of its scenario, its thread reinforced by the intricacy of its setting, Spielberg composed Minority Report to be a fast-paced union of brains and virtuoso sequences. This is pure, deftly stylized cinema hurtling from one crisis to another with incredible speed and breadth and cunning. John Williams’ thrilling and playful score forms a pitch-perfect marriage with the breakneck proceedings, and the noirish storyline, wrapped inside its science-fiction framework, gives way to an uncommonly exciting motion picture of substantial characters and profoundly involving sci-fi applications. The visionary quality of Minority Report‘s cinematic world is matched solely by its endless influence on both film and real-world technology since its release. But most importantly, its influence never overwhelms the picture itself. Spielberg’s film is ingenious not only for the filmmaker’s countless moments of cinematic resourcefulness and aesthetic wonderment, but for how every fascinating bit of technology or invention suffused into the film has a direct implication on the forward-moving plot and its intensely feeling characters, and furthermore, how the plot expounds an underlying philosophical question. Deepening the kinetics of an adventure, Minority Report maintains the power of a dynamic, ceaselessly entertaining, cerebral series of ideas born in the limitless mind of Philip K. Dick. Indeed, few films have ever been so much all at once and done so with such sublime artistry.

Bibliography:

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). London. Faber and Faber, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review