The Definitives

Metropolis (1927)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

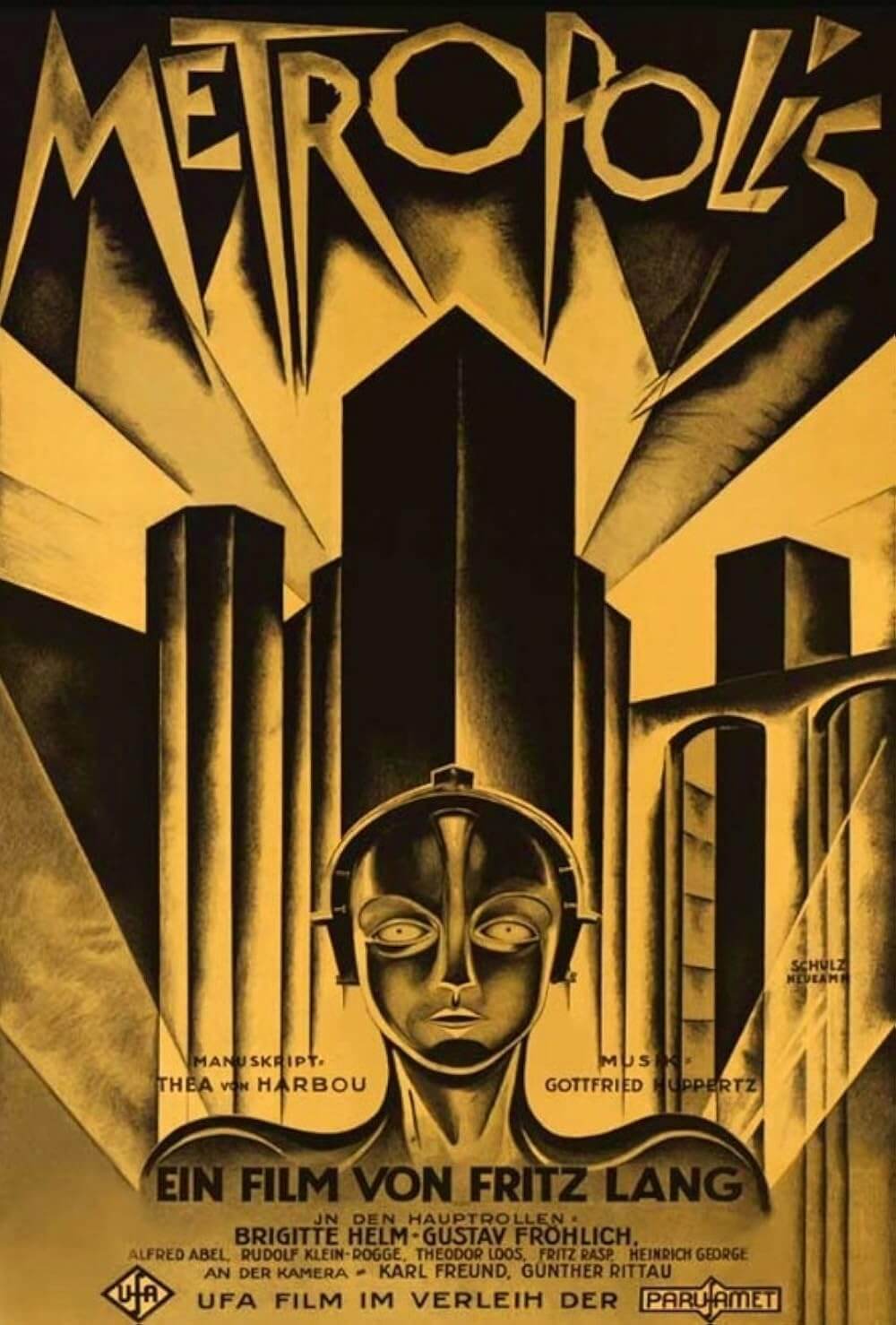

Metropolis contains such magnificent visuals that all else about the film recedes, allowing its all-consuming mythical status to take over. A technical masterwork of the Silent Era by Austrian director Fritz Lang, the 1927 picture’s incredible, cutting-edge special effects and futurist imagery have become immeasurably iconographic and made the picture a landmark of influential science-fiction filmmaking. Lang set out with the ambition to produce a film costlier and grander in scope than anything achieved before, enlisting thousands of extras, colossal sets, and sights never imagined for a motion picture. However, as a narrative experience, the sociopolitical subtexts present in the film would be less imposing, though not by design. Attempts by Lang and his wife, Thea von Harbou, who wrote the novel on which the film is based, to imbue their co-written screenplay with meaningful themes about the ongoing struggle between slave labor and their masters result in mixed messages between the film’s Marxist indoctrination and its curious sentimentality. And the ironic, notorious history of the film’s production under its mercilessly authoritarian director, as well as its subsequent favor among members of the Nazi party, further complicate the filmmakers’ intentions and Metropolis‘ lasting impact, which, nonetheless, supersede any contradictions or questionable associations the film may have by the sheer force of its mythic standing.

Fritz Lang was born in 1890 in Vienna to an architect father and a Jewish mother, the latter of whom converted from Judaism to Catholicism and raised young Fritz as a Catholic. Though initially following in his father’s footsteps, he lived a poor and bohemian lifestyle as he studied art at the Academy of Art and Design in Munich and later the Académie Julian in Paris, where he discovered himself and his lifelong affection for female escorts, painting, and tales of murder. In Paris, he later recalled seeing The Great Train Robbery (1904) and other early works of cinema that made him realize “you could also paint using a camera.” But his yet-unrealized aspirations to become a professional painter or filmmaker would have to wait until after World War I; Lang volunteered for duty in January of 1915 and listed his occupation as “artist,” though his education would ensure his rise to the rank of lieutenant. Lang’s enthusiasm toward the “adventure” of war earned him several medals but also several injuries, including one that left him nearly blind in his left eye, where he would wear a monocle for his remaining years—an infamous signifier of the film director’s prying, detailed-obsessed exactitude. Then again, contradictory stories have arisen concerning the origins of Lang’s monocle, suggesting Lang wore it before the war or even that he adopted it after the war when nitrate film stock exploded in his face. Wherever its origins lie, the opposing stories underscore the truth that Lang’s early life is suspect because the later filmmaker often exaggerated or falsified his history in interviews for anecdotal entertainment.

While recovering in the hospital from war injuries, Lang began to keep a journal of his day’s events, thoughts, and story ideas, and he would continue to journal his daily activities to an almost compulsion-level extreme until the end of his life. With the war ending in 1918, Lang was torn between which path he should take, painting or filmmaking, and he soon had the opportunity to share many of his journaled ideas with a young Erich Pommer, the German producer who oversaw the Bild-und-Film-Amt (Bufa), the army’s department of propaganda and entertainment, which later absorbed into Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa), arguably Germany’s greatest film studio. Pommer hired Lang to write screenplays for his production company, Decla, and Lang quickly yearned to become a director. Within a few short, busy years between 1918 and 1924, Lang began directing increasingly ambitious motion pictures and rose to the height of the German film industry with titles like the two-part thriller The Spiders (1920), The Wandering Image (1920), and the four-hour Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922). During this prolific period, Lang met Thea von Harbou, who would co-author a number of his screenplays; the two would be married in 1920, and together they explored themes that reflected the tortured postwar identity of Germany through perversity, criminality, and the fantastic—themes that, though pointedly German at the time, nonetheless persisted in Lang’s work until the end of his long career. In 1924, Lang released the spectacle Die Nibelungen, another lengthy two-parter and a fantasy based on a thirteenth-century epic poem called Nibelungenlied. The hugely popular and successful production showcased the director’s embrace of special effects within the camera, which would be taken to their limits in his next film.

Lang’s self-serving anecdote about how the idea for Metropolis came to him was told again and again by the director, as well as numerous biographers and film historians since. Standing on the deck of the Deutschland as it approached American ports in the autumn of 1924, Lang, there with Pommer, supposedly eyed the sprawling New York City from afar and was jolted by this “city of the future”—thus the seed of Metropolis was born. Lang’s story was just great myth-making on his part, compelled not only by his bombastic ego but also by the producing studio, Ufa, to make a much-needed lasting impression on the American market and sustain the German film industry. Indeed, in early-to-mid 1924, Erich Pommer had already begun telling people about Lang’s next script for Metropolis while the director was putting the finishing touches on and conducting publicity tours for Die Nibelungen. Moreover, as early as three months before his supposedly inspiring trip to America, Lang and von Harbou had vacationed together to, according to an Austrian newspaper, “finish the screenplay for their new film Metropolis.” Von Harbou had often written novels before her screenplays or completed novelizations for release alongside a given film. In the case of Metropolis, screen credit was given to von Harbou for the source “based on a novel by Thea von Harbou.” Regardless of when the story was completed, pre-production meetings at Ufa began by the end of 1924, and Pommer would attempt to persuade, sometimes unsuccessfully, the studio’s best talent to once more work with the already demanding director of some ill-repute for his most elaborate production yet.

Lang and von Harbou’s story is a modern retelling of the Tower of Babel, prefaced and concluded by the epigram, “The mediator between the brain and the hands must be the heart!” High above the futuristic city of Metropolis is its master, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), resident “brain” of the bourgeoisie leisure class, among them his spoiled son, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich). Below are the “hands” who toil over the Heart Machine, workers like the rugged foreman Grot (Heinrich George). Deep beneath the city, under awful conditions, the proletariat strains themselves on the punishing machines, but further down beneath in subterranean levels are catacombs where word of suspected rebellion brews. Freder sympathizes with the workers and soon sides with them, his interest piqued by his attraction to Maria (Brigitte Helm), a figurative character amalgamating Christ and the Madonna, who brings children to the surface to see how the upper classes live. In turn, Freder visits the Heart Machine and witnesses the workers’ subjugated efforts first-hand, and later learns of the secret meetings held in the catacombs. Attending a secret meeting, Freder watches as Maria stands in a cave amid spire crucifixes and the Reichsadler eagle (later used in Nazi imagery) and prophesizes to the virtually zombified workers that a mediator will come to bring an understanding between Joh Fredersen and the labor class. Inspired, Feder believes he can serve as the prophesized mediator.

Above, Joh Fredersen learns of his son’s betrayal and the workers’ slipping productivity within his enforced 10-hour day, and he schemes with Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), an inventor with a somewhat possessed robotic hand (an influence for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove). Rotwang reveals he can build Machine-Human facsimiles and shows Fredersen the living inner skeleton of a female robot he’s built. Fredersen permits Rotwang to create an identical cyborg of Maria to infiltrate the workers. But Rotwang also wants revenge on Fredersen for stealing his love, a woman named Hel, who died giving birth to Freder, and so Rotwang plots for his false Maria (distinguishable only by her darkened eyes and lips, her sharp movements, and the glint of madness in her eyes) to provoke an uprising. At the robo-Maria’s order, the workers leave their children behind in the underground city and rush to destroy the machines that power the city above. Fredersen allows the revolt to continue, if only because he knows the machines will back up and incite a flood in the workers’ underground home. Soon, the flood wipes away the workers’ city—though Freder and the real Maria narrowly rescue the children. Once the workers learn of this, they believe their children dead and blame who they believe to be Maria, resolving to burn the robo-Maria “witch” at the stake. The robo-Maria is revealed to be a robot as it goes up in flames; now the mob turns to Fredersen. Elsewhere, Freder saves Maria from the maddened Rotwang and fights him off until the villain falls to his death. With the mob calmed once they learn of their children’s safety, Freder lives up to his promise and pronounces himself the Heart: “The mediator between the brain and the hands.”

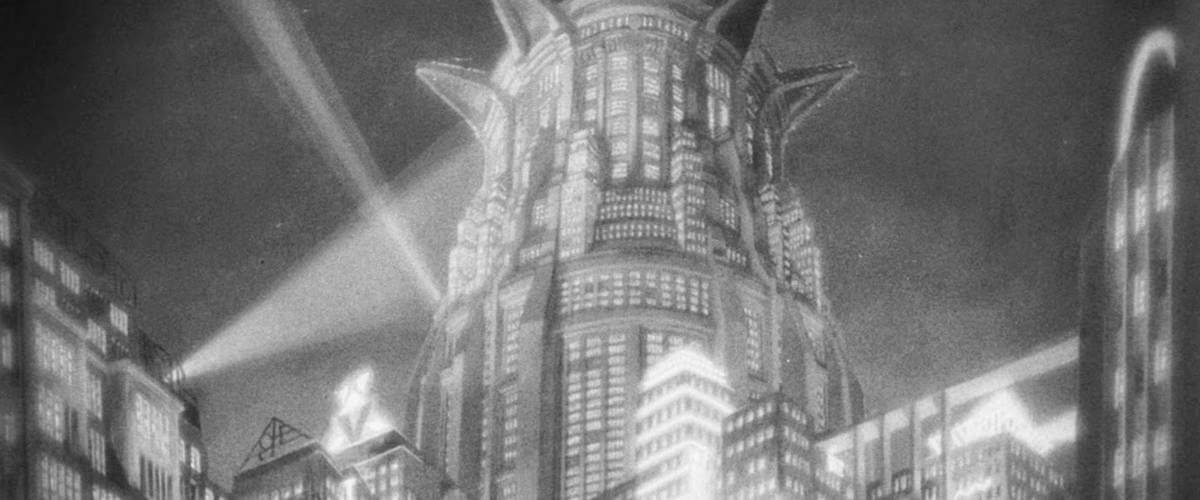

With the screenplay finished, Lang met with his Ufa team to plan the costly production, which, from the beginning, was never expected to earn profits but instead to encourage American investors to put capital into German films. Cameraman Günther Rittau, special effects designer Eugen Schüfftan, and art director Erich Kettelhut worked together to plan countless in-camera tricks to realize this futuristic cityscape once its design had been established—with palpable influences from modern art movements such as Art Deco, Dada, Expressionism, and Surrealism, while the design for the Tower of Babel was more classical, drawn from Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s 1563 painting. Sketches and blueprints were decided over, many debates were had, and the production schedule for filming and animation was grueling. While Lang oversaw rehearsals of the film’s many heart-clenching performances, Schüfftan and cinematographer Karl Freund began shooting scenes with the miniatures (cars, airplanes, buildings, etc.), which were shot using stop-motion photography. Schüfftan had created “the Schüfftan process” for an unrealized production of Gulliver’s Travels and used it here, employing mirrors to blend miniatures, scale sets, and actors into a single shot. Sequences such as this would only appear onscreen for a few brief moments but would take weeks to set up. The process was so untested that one such setup was botched by a cameraman and required nearly a month to reshoot.

With the screenplay finished, Lang met with his Ufa team to plan the costly production, which, from the beginning, was never expected to earn profits but instead to encourage American investors to put capital into German films. Cameraman Günther Rittau, special effects designer Eugen Schüfftan, and art director Erich Kettelhut worked together to plan countless in-camera tricks to realize this futuristic cityscape once its design had been established—with palpable influences from modern art movements such as Art Deco, Dada, Expressionism, and Surrealism, while the design for the Tower of Babel was more classical, drawn from Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s 1563 painting. Sketches and blueprints were decided over, many debates were had, and the production schedule for filming and animation was grueling. While Lang oversaw rehearsals of the film’s many heart-clenching performances, Schüfftan and cinematographer Karl Freund began shooting scenes with the miniatures (cars, airplanes, buildings, etc.), which were shot using stop-motion photography. Schüfftan had created “the Schüfftan process” for an unrealized production of Gulliver’s Travels and used it here, employing mirrors to blend miniatures, scale sets, and actors into a single shot. Sequences such as this would only appear onscreen for a few brief moments but would take weeks to set up. The process was so untested that one such setup was botched by a cameraman and required nearly a month to reshoot.

Filming began in May of 1925 and ended in October of 1926, a production of staggering length and with a price tag of five million marks. Some 38,000 extras were hired in addition to the principal actors, and if moviegoers were meant to think the 10-hour workdays imposed by Joh Frederson were cruel, Lang pushed his cast and crew much harder, with morning-until-midnight work hours and rarely a Sunday off. Fröhlich wrote in his autobiography, “In scenes of physical suffering, he tormented the actors until they really did suffer.” Lang forced Fröhlich to reshoot a scene for two days where Freder falls to his knees before Maria, always finding some excuse (an incorrect camera angle, his acting wasn’t as “deeply felt” as it should be) to shoot it again, until Fröhlich could barely stand. Lang was hardest on reluctant actress Brigitte Helm, whom he corrected fussily, if not torturously. For weeks, Helm, then a teenager, was forced to endure “liquid wood” molds for the robo-Maria costume, requiring her to keep a rigid stance for hours on end. The molds had been taken while Helm was standing, but for the robo-Maria’s throned unveiling, the actress was required to be seated, thus the mold caused her great pain. (Rittau had conceived the sequence’s effect, where rings of light encircle robo-Maria and simultaneously rotate up and down and around her, by shooting a silver ball looping in front of a black velvet backdrop.) Lang’s autocratic, bullying behavior on the set extended beyond the primary cast; he almost came to blows with designer Otto Hunte and proved temperamental when decisions were made without his prior approval. And whatever frustrations he had about minor losses of control were exacted on his cast and crew tenfold.

For the flooding sequence, Lang rounded up hundreds of slum kids from around Berlin and forced them into cold water for nearly two weeks of shooting; their torment was offset by regular doses of warm meals, toys, and cocoa. For the adult extras, Lang benefited from Berlin’s high unemployment rates when he needed to film a dream sequence where half-naked men leap into the mouth of Moloch, god of fire, as imagined by Freder when he first sees the Heart Machine. Though the sequence appears swelteringly hot in the film, in reality, the set was freezing cold and filled with smoke, and the steam from the smoke created a chilly drizzle that fell onto the heads of shivering, hungry, skinny, jobless men. Lang’s cruel orchestration of his picture culminated during the filming of the Heart Machine’s destruction, where the puppeteer-director literally dangled his extras from strings to create the impression that they were blown away from the machine. It wasn’t all freezing temperatures; for Maria’s retelling of the Tower of Babel legend, Lang required 1,000 extras to shave their heads and drag huge actual stones through an actual desert landscape. Between shots, the extras could do nothing but wait around and get horribly sunburned. The cast and crew whispered about Lang’s “abnormal” approach and demands, believing him nearly murderous. When Lang’s methods caused the production to be over-schedule and over-budget, Pommer, who was the voice of reason on-set, was blamed by the studio, and so Lang was free to continue unhindered. One of the last, most dangerous sequences entailed burning robo-Maria at the stake, and Lang insisted Helm experience the heat of real flames for authenticity; while filming the scene, Helm’s dress caught fire and, after being rescued by Lang and the on-set fire department, she passed out in Lang’s arms.

M etropolis premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo moviehouse in Berlin on January 10, 1927, with a selection of Germany’s most significant figures in art and society in attendance. To accompany the spectacle onscreen, composer Gottfried Huppertz provided the music with a live orchestra, and the audiences reacted with “spontaneous applause,” according to spectators. Once the curtain calls were over, the afterparties rang with celebration from the cast and crew, and Lang enjoyed the spotlight and adulation of those who praised his work that evening. However, over the coming days, weeks, and months as Metropolis‘ release expanded, the film was met with censure from many critics who condemned Lang’s liberal borrowing from the likes of the Bible, Jules Verne, and Karl Marx, amid several other sources. They deemed the film an intellectual bore despite its monumental visuals. As a result of the response and the film’s original 153-minute runtime, Ufa recut the picture to two hours and reissued it across Germany eight months later. Elsewhere, Ufa and Paramount had formed an organization called Parufamet to distribute American films in Germany, and vice versa. But the Americans also negotiated editing rights in the Parufamet deal, and Metropolis was reduced to 107 minutes in a U.S. cut that removed many of the subplots and changed the intertitles to achieve this length. Through various hack-and-slash jobs done on the film over the years, none was worse than music producer Giorgio Moroder’s reedit in 1984, a release year chosen for its Orwellian significance. Moroder’s version incorporated rock songs from Adam Ant, Pat Benatar, Loverboy, Freddie Mercury, and Billy Squier into the soundtrack. Lang’s preferred cut—the original—ran for a mere ten weeks in Berlin, but the complete version has since been lost. Only as recently as 2008 has a near-whole version of Metropolis, though long lost to time, been found at the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina; from this, missing scenes have been scratchily restored from a 16mm reduction from the original negative. Widely celebrated for elaborating on the shortened narrative strains of abridged cuts over the years, the 148-minute version from the Museo del Cine has been widely circulated as The Complete Metropolis.

etropolis premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo moviehouse in Berlin on January 10, 1927, with a selection of Germany’s most significant figures in art and society in attendance. To accompany the spectacle onscreen, composer Gottfried Huppertz provided the music with a live orchestra, and the audiences reacted with “spontaneous applause,” according to spectators. Once the curtain calls were over, the afterparties rang with celebration from the cast and crew, and Lang enjoyed the spotlight and adulation of those who praised his work that evening. However, over the coming days, weeks, and months as Metropolis‘ release expanded, the film was met with censure from many critics who condemned Lang’s liberal borrowing from the likes of the Bible, Jules Verne, and Karl Marx, amid several other sources. They deemed the film an intellectual bore despite its monumental visuals. As a result of the response and the film’s original 153-minute runtime, Ufa recut the picture to two hours and reissued it across Germany eight months later. Elsewhere, Ufa and Paramount had formed an organization called Parufamet to distribute American films in Germany, and vice versa. But the Americans also negotiated editing rights in the Parufamet deal, and Metropolis was reduced to 107 minutes in a U.S. cut that removed many of the subplots and changed the intertitles to achieve this length. Through various hack-and-slash jobs done on the film over the years, none was worse than music producer Giorgio Moroder’s reedit in 1984, a release year chosen for its Orwellian significance. Moroder’s version incorporated rock songs from Adam Ant, Pat Benatar, Loverboy, Freddie Mercury, and Billy Squier into the soundtrack. Lang’s preferred cut—the original—ran for a mere ten weeks in Berlin, but the complete version has since been lost. Only as recently as 2008 has a near-whole version of Metropolis, though long lost to time, been found at the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina; from this, missing scenes have been scratchily restored from a 16mm reduction from the original negative. Widely celebrated for elaborating on the shortened narrative strains of abridged cuts over the years, the 148-minute version from the Museo del Cine has been widely circulated as The Complete Metropolis.

But if the restoration has confirmed anything beyond the visual force of Lang’s film, it has reinforced the notion that the story of Metropolis is trivial, confused, and illogical no matter the cut being viewed. In a scathing but incisive review published in the New York Times in April 1927, science-fiction author H.G. Wells (The War of the Worlds, The Time Machine) summed up the film and its implausible predictions about the future nicely, writing, “It gives in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.” To be sure, Wells’ discussion about the “muddlement” of the machines and progress is difficult to discount, as it tears down any hope for logic or meaningful sociopolitical commentary in Metropolis. Consider how laborers in the film toil away to maintain a city where the middle-class, political presence, and civil servants are unseen or nonexistent. Who else but the labor class and upper crust inhabits this city? And why must the laborers waste away on ostensibly nonfunctional machines? Wells observed, “Much stress is laid on the fact that the workers are spiritless, hopeless drudges… But a mechanical civilization has no use for mere drudges; the more efficient its machinery the less need there is for the quasi-mechanical minder.” Wells does not see a benefit from the intense labor depicted in the film, and so he wonders what the labor produces, if anything, and for whom? Lang later admitted to interviewer Peter Bogdonovich that the central, simple-minded theme of the picture was “unrealistic” and “a fairy tale” and conceded, “I was very interested in machines.” Lang’s fascination does not extend beyond the machines themselves, their daunting beauty, sharp lines, and imposing stature within his frame. He does not intentionally intellectualize the machines, and therefore they are empty components of the narrative. (Wells said of the narrative, “Originality there is none. Independent thought, none.”)

Without a doubt, the advanced machines are not the origin of conflict in Metropolis, nor does the film’s treatment of technology correspond to science-fiction worlds often paranoid about the threat of robotics and artificial intelligence—established in literature before Metropolis in everything from Karel Čapek’s robot play R.U.R. to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The danger of the machines is inherent to how humans use those machines through cruel labor and manipulation. But in a world capable of a convincing human replicant, why is there a need for such drudgery? Nevertheless, the machines, even the robo-Maria, do what they’re told and nothing more, and the human worker (exclusively male; women are either Madonna or the Whore) sweats physically, fruitlessly, to the end of his workday no less like a hamster on a wheel, serving as “living food” for machines, for which humans feel a dogged need to maintain to their own limits. Wells pointed out, “The contrivers of this idiotic spectacle are so hopelessly ignorant of all the work that has been done upon industrial efficiency that they represent him as working his machine-minders to the point of exhaustion so that they faint and machines explode, and people are scalded to death. It is the inefficient factory that needs slaves; the ill-organized mine that kills men.” In other words, in the world of Metropolis, such a grand and impeccably designed city would be impossible given the complete lack of efficiency shown operating underneath it. Additionally, the film dreams up a fantastical and much-romanticized resolution to its industrialized regimentation when the forces of labor and management meet in a grand public display and agree to mediation through sentimentalized morality. In its expressive, blown-up dramatic quality, the film operates more like an opera and certainly earns the adjective “operatic”—excessively so, even for viewers accustomed to the emphatic drives of Silent Film stylization.

Conceived largely by von Harbou, who later joined the Nazi movement, the Marxist themes in Metropolis portray the struggle between management and labor, and through the course of the film, share several eyebrow-raising correlations with the origins of Nazism. When workers rise up to usurp the above-class authority in Metropolis, the onscreen revolution brings to mind that oft-associated quote from Joseph Goebbels from a 1928 speech: “The political bourgeoisie is about to leave the stage of history. In its place advance the oppressed producers of the head and hand, the forces of labor, to begin their historical mission.” Goebbels’ (coincidental?) reference to the “head and hand” should not be overlooked, nor should the way the working class in Metropolis proves to be unruly and ultimately in need of a “mediator.” Freder, though born of bourgeois blood, sympathizes with the workers and serves as a leader and intermediary, just as Adolf Hitler rose from the ashes of World War I to command the German working class to reestablish their country’s former glory through the absolute control of Nazism. Of course, the political lines are simplified by this argument, which presupposes many correlations, all surely unintended by Lang. Yet the viewer cannot help but become suspicious as both Freder and Hitler become figureheads of their newly empowered labor force. Even still, in the end of Metropolis, there exists no satisfying accountability for the “brain” nor retribution against Joh Fredersen for his crimes against the workers, which, if this were indeed a Nazi-approved production, would have demanded Fredersen’s punishment. (Indeed, Goebbels later demanded a new ending for Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) because, in the end, the criminal gets away with it.) At any rate, any such associations between Metropolis and Nazism are a stretch and far too reliant on historical coincidences—eerie and suspicious coincidences, but coincidences nonetheless. Of course, all of this is contingent on the need for a labor force in Metropolis, which, according to Wells’ astute arguments, is either completely unnecessary or completely incompetent.

Conceived largely by von Harbou, who later joined the Nazi movement, the Marxist themes in Metropolis portray the struggle between management and labor, and through the course of the film, share several eyebrow-raising correlations with the origins of Nazism. When workers rise up to usurp the above-class authority in Metropolis, the onscreen revolution brings to mind that oft-associated quote from Joseph Goebbels from a 1928 speech: “The political bourgeoisie is about to leave the stage of history. In its place advance the oppressed producers of the head and hand, the forces of labor, to begin their historical mission.” Goebbels’ (coincidental?) reference to the “head and hand” should not be overlooked, nor should the way the working class in Metropolis proves to be unruly and ultimately in need of a “mediator.” Freder, though born of bourgeois blood, sympathizes with the workers and serves as a leader and intermediary, just as Adolf Hitler rose from the ashes of World War I to command the German working class to reestablish their country’s former glory through the absolute control of Nazism. Of course, the political lines are simplified by this argument, which presupposes many correlations, all surely unintended by Lang. Yet the viewer cannot help but become suspicious as both Freder and Hitler become figureheads of their newly empowered labor force. Even still, in the end of Metropolis, there exists no satisfying accountability for the “brain” nor retribution against Joh Fredersen for his crimes against the workers, which, if this were indeed a Nazi-approved production, would have demanded Fredersen’s punishment. (Indeed, Goebbels later demanded a new ending for Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) because, in the end, the criminal gets away with it.) At any rate, any such associations between Metropolis and Nazism are a stretch and far too reliant on historical coincidences—eerie and suspicious coincidences, but coincidences nonetheless. Of course, all of this is contingent on the need for a labor force in Metropolis, which, according to Wells’ astute arguments, is either completely unnecessary or completely incompetent.

After finishing Metropolis, Lang would go on to make more successful pictures for Ufa, including Spies (1928), Woman in the Moon (1929), his masterful M (1930), and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Meanwhile, Hitler rose to power, and Joseph Goebbels became the head of the National Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Jewish businesses were being condemned by the National Socialist party, and suddenly Lang was being identified as Jewish in film-related publications. (Whether or not this exposure of Lang’s family line could be attributed to von Harbou, who was divorced from her husband by 1933, remains uncertain.) That Lang was at the top of the German film industry and of Jewish heritage was not overlooked, though Goebbels was a definite fan of Lang’s films. Many in the European film industry (Billy Wilder, Max Ophüls, Fred Zinnemann, etc.) had already begun to flee Hitler’s impending raid on surrounding countries, but it took the German Board of Film Censors banning The Testament of Dr. Mabuse from exhibition to incite Lang (who received favorable treatment from Goebbels and appeared alongside him, allegedly in full Nazi dress, at least once at a public conference), to join the others and head to Hollywood. But before Lang escaped, he met with Goebbels about their censorship of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, and during that meeting, Goebbels asked Lang, on behalf of Hitler, to head the German film industry. Despite Lang’s lineage, Goebbels vowed to make him an “honorary Aryan” and insisted, “We decide who is Jewish or not.” After all, Hitler “loved” Metropolis, and the Nazis would later embrace the film’s imagery in their own visual iconography, from the Reichsadler eagle to the use of massive lines and architecture employed for Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 propaganda piece Triumph of the Will. Lang was on a train the next day, leaving everything behind.

Then again, certain facts of Lang’s encounter with Goebbels, often told and retold by Lang with varying detail, have since been debunked and, though probably not completely false, the story was surely edited and sensationalized by Lang for maximum peril and excitement, further adding to his own mythology, and the film’s. Perhaps it’s a case of Lang’s penchant for anecdotal entertainment, not unlike tales surrounding his monocle. In his book Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, author Patrick McGilligan posits that Lang’s story was likely a combination of multiple visits with Goebbels. However true or untrue, as a result of Lang’s brief association with Goebbels, not to mention von Harbou’s Nazi affiliations, it’s virtually impossible to watch Metropolis today and not see why its obsession with machine-like movements and larger-than-life imagery impressed the Nazis, who were themselves so dependent on visual iconographies to support the authority of their party. When city workers march in lines to and from the job, the procession and its carefully orchestrated movements recall Nazi rallies—the “mass-ornament”—and their orderly arrangements are so frightening in their mechanical-yet-human physicality. These associations, compounded by the weak and idealistic narrative of the film, would leave Metropolis a masterpiece of visual distinction, where the aesthetic power of an image is greater than the meaning of that image. Lang would later realize the error of his film’s rather ambiguous, under-explored message, attributing the politics to von Harbou (Lang had originally considered an ending where Maria and Freder fly off in a spaceship but conceded to his wife). In an interview with the Cahier du Cinema in 1965, he suggested there was an unnecessary moral element in the film, but “the problem is social, not moral,” he said.

In the 1920s, the film’s oversimplified ideological message about industrialization would have been more relevant, even if most critics responded to its social commentary with intellectual rebuffs. Today, the message is far less applicable, but Metropolis‘ lasting effect is how Lang has delighted us with the scope and splendor of the city’s design. Given the film’s bombastic, unforgettable sights, it’s impossible to grasp the impact of Metropolis on its original Berlin audiences in 1927. We see a grotto of the future, Freder’s “Club of the Sons”—a prehistoric-looking garden that seems like something out of Jules Verne, filled with enormous plants and willing consorts. Above, Fredersen’s office is bare save for a rear-projected clock to track his 10-hour day. Far below, if the Heart Machine itself weren’t impressive enough, Lang shows us a dream image where Freder sees the machine as the altar of an ancient temple upon which workers are lined up and sacrificed into a smoky abyss. Zombie-like workers marching in rows; the under-city flooding in mass destruction; hundreds of children grasping in desperation; robo-Maria rising from her throne of light rings, and then stepping forward into eternity; Helm as a simulacrum, contorting her gestures and expressions; a collage of eyes gazing in Dali-esque voyeurism; the Tower of Babel rising above the cityscape. But no image is more powerful in Metropolis than the cityscape itself—with moving cars, trains, planes, and pedestrians, all in motion before the great Tower. The shot is even more impressive in a night sequence where skyscrapers are illuminated by bright streetlights, flashing signage, and glowing buildings.

The noted divergence between Metropolis‘ narrative and thematic forms against the film’s immeasurable visual luster has been a point of contention since the picture was first screened, but the degree to which the film has been embraced and emblematized in the decades since its release has ensured its visual impact is timeless. Countless examples from science fiction have been inspired by its imagery. Its sprawling cityscapes can be found in Blade Runner (1982), The Fifth Element (1997), and Dark City (1998); its robo-Maria is the mother of nearly every robot in film history, from Gort in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1957) to the titular RoboCop (1987); and Snowpiercer (2014) retold a similar tale about the lower classes revolting against those who rule them. The controversy that surrounds the making of the picture and, through the lens of hindsight, the available associations to various political factions (from the Bolsheviks to Nazism), leave Metropolis an important historical marker, as opposed to an enduringly germane timeless classic. Lang’s film belongs on a list next to D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), David O. Selznick’s production of Gone with the Wind (1939), and even Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will as a politically or thematically problematic motion picture whose technical achievements, influence on other filmmakers, and place in history has been firmly established and whose mythology is transcendent.

Bibliography:

Elsaesser, Thomas. Metropolis. (BFI Film Classics). 2nd Edition. British Film Institute, 2012.

Kreimeier, Klaus. The Ufa Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review