The Definitives

Melancholia

Essay by Brian Eggert |

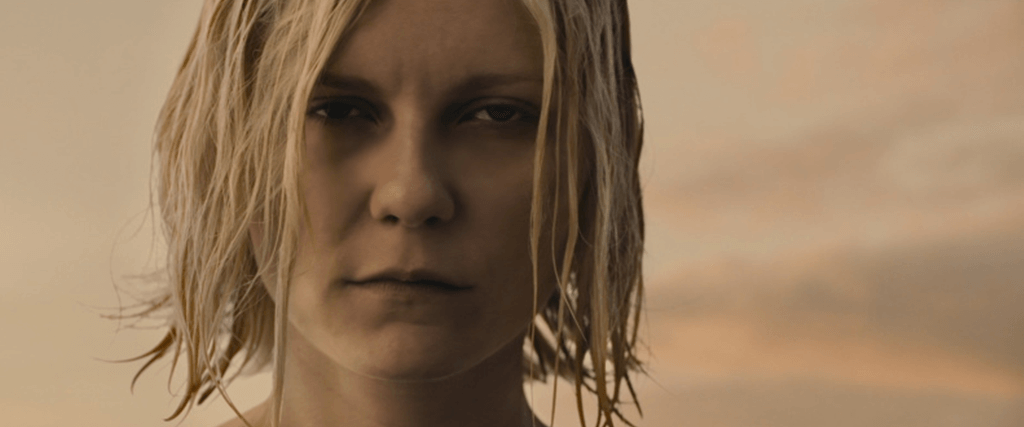

Lars von Trier’s Melancholia opens with Kirsten Dunst’s tired, darkened eyes. They look as though her character, Justine, hasn’t slept in days. Her stringy hair frames her face, pale and devoid of expression. Behind her, dead birds fall from the sky. The light around Justine has an uncanny, vaguely purple glow, which carries into the next eight minutes of sublime images, each more apocalyptic than the last, foretelling the world’s end. Employing concepts usually found in science fiction and disaster fare, von Trier weaves his genres into a melodrama whose protagonist embodies the filmmaker’s depression. Described in the film’s press notes as a “beautiful film about the end of the world,” Melancholia also represents an oddity in the Danish director’s career. It contains a harmony between the devastating emotional effect most prominent in his narratives with a stripped-down aesthetic. But it’s presented with a formal mastery that combines the operatic monumentality of his leitmotif—Richard Wagner’s prelude to Tristan and Isolde—with painterly imagery. At once a commercial project by von Trier standards and a profoundly moving, mysterious film, Melancholia echoes the emotions and grim visions of its protagonist, an onscreen counterpart for the director. To watch the film is to experience how depressives register the pain of existence and may even look to The End with a blissful, gracious heart.

Von Trier conceived Melancholia out of conversations with his therapist. According to the Danish Film Institute, “A therapist told him a theory that depressives and melancholics act more calmly in violent situations, while ‘ordinary, happy’ people are more apt to panic. Melancholics are ready for it. They already know everything is going to hell.” Contemporary psychotherapists characterize this tendency among depressives as pain catastrophizing, which interprets the world and events therein through a dark lens that reflects their inner angst. How people react, and their states of mind through the crisis until the inevitable, is the driving theme of Melancholia, a psychodrama set in an allegorical world, where an unavoidable collision between Earth and a rogue planet named Melancholia means the end of everything—not just life on our planet but everywhere. Justine sees visions of a massive gas giant dwarfing Earth and feels what’s coming. “I know things,” Justine tells her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg). “And when I say we’re alone, we’re alone. Life is only on earth, and not for long.” However grave the impetus, von Trier conceived the film as what Thomas Elsaesser deemed a “thought experiment” to work through his personal experiences with depression in a hypothetical scenario, serving as drama therapy.

From this starting point, von Trier sought a disaster that would capture how a melancholic would behave in an apocalypse. After scouring the web for ideas, he settled on a planetary collision with a planet “hiding” behind the Sun. At the same time, von Trier had been corresponding with Penélope Cruz, who had reached out with hopes of working together. She suggested he adapt Jean Genet’s 1947 play The Maids, based on Christine and Léa Papin, real-life sisters who worked for the same mistress, whom they killed in a highly publicized story. Von Trier folded those two concepts into one another, settling on the story of two sisters, the depressive Justine and her so-called normal sister Claire, who react quite differently upon learning that a gas giant named Melancholia is racing toward Earth. Working closely with his assistant, Vinca Wiedemann, von Trier dictated much of the script. Tremors in his hands from his depression, made worse by his reliance on vodka and various drugs for many years, prevented him from writing alone. Still, having sobered up since making Antichrist (2009), he completed the script with the help of Wiedemann, who asked questions and served as a sounding board to refine his ideas. Ultimately, scheduling conflicts prevented Cruz from playing Justine, and Paul Thomas Anderson advised von Trier to offer the part to Kirsten Dunst.

Before going further into Melancholia, it’s important to note that stepping into the film space of any Lars von Trier production means traversing its director’s many personal layers and contradictions. It’s never a simple matter of engaging with the text alone. The auteur and his output are inextricable, and while possible to examine each in a silo, it’s a richer experience to consider both simultaneously. Beyond prompting discussions and scholarly debates in psychological, philosophical, and artistic fields, Melancholia proved irresistible for many who sought to get deeper into von Trier’s headspace and witness, through a metaphoric story, a personal experience of self-destructive thinking. This is especially true given his thoroughly publicized bout of depression before the film’s release, turning Melancholia into a kind of performative and personal art project that goes beyond the purely mimetic. So, when considering Melancholia in relation to its creator, some context is needed to situate the film within that framework. This is a challenge since von Trier has defined and refined his identity several times over, underscoring how he remains a self-constructed figure who makes self-reflective films.

Born Lars Trier in 1956, he was the second child of Inger Høst and Ulf Trier, progressives with liberal views on art, parenting, and politics. His mother was a staunch communist, his father a Jewish social democrat, and though their refusal to discipline him marks a kind of extreme freedom, von Tier told critic Stig Björkman that therapy made him realize his childhood of nudist camps and artist communes wasn’t as free as he once believed. On her deathbed, his mother admitted that his Jewish identity was false; his father had actually been her former boss, Fritz Michael Hartmann, whose family line contains several of Denmark’s most famous composers. Inger wanted a child with an artistic sensibility, so he became a kind of “genetic project.” Continuing in that spirit, he fashioned an artistic identity for himself as “Lars von Trier,” adding the distinguished “von”—modeled after Erich von Stroheim—for the first time in a newspaper article in 1976, well before he had settled on an artform to practice. Indeed, he started as a painter and writer before enrolling in the University of Copenhagen’s film studies program. Three years after applying to the competitive Danish Film School in 1979, he graduated with accolades. Von Trier had earned a literal and figurative name for himself, and his new name’s faux aristocratic airs would at once elevate him and provoke the establishments he would later clash with.

Along the way, von Trier has further crafted his auteur persona and public image. Scholar Peter Schepelern observes that von Trier’s artistic agenda is “not primarily to make film but to construct Lars von Trier, the auteur filmmaker.” Another way of seeing von Trier’s project of self-construction is a search for the Self through his chosen artform. The director acknowledges that his art and identity are interwoven, and his public persona has evolved over the years just as his aesthetic has. He has caused several controversies from his irreverent approach to interviews and during his appearances at the Cannes Film Festival—the press conference for Melancholia, above all, is his most scandalous—which double as (self)promotional tactics to call attention to his films. From making cameos in his work to narrating them, from announcing artistic limits for himself only to break them later in acts of self-sabotage, von Trier builds and defies his mythology. His films are equally confrontational, often pushing his audience to their emotional or representational limits. Whether his efforts are the work of a genius, a disingenuous fraud, a shameless provocateur, or a complex artist, his role as a showman remains among the only constants in his career, while his output often takes on various formats.

Since von Trier started making features in the 1980s, his films have been categorized and narrowed by the audience’s tendency to segment them into trilogies. His earliest works, usually called the Europe Trilogy, include The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987), and Europa (1991). Each represents von Trier exploring aesthetics through a rich amalgamation of visual influences and allusions, intent on perfecting an intellectual style and rigid technique over an interest in narrative or characters. In the years to follow, many of his films would be lumped into unofficial trilogies such as this, though scholar Linda Badley notes his work more often fits into duologies, whereas most of his trilogies contain one outlier. For instance, he became more invested in emotions than aesthetics with Breaking the Waves (1996), part of the devastating “Golden Heart” trilogy—films about beleaguered innocents who sacrifice themselves to the predatory world—which, more accurately, belongs in a duology with Dancer in the Dark (2000). His feature between them, The Idiots (1998), stands on its own as the second feature of Dogme 95, the movement von Trier spearheaded alongside three “brothers,” posing various formal constraints, including a ban on crediting the director. Still, a stylistic minimalism purveys his output from Breaking the Waves into his next proposed trilogy, USA: Land of Opportunities, which started with Dogville (2003) and ended with Manderlay (2005), though some have lumped The House That Jack Built (2018) in that grouping—perhaps hastily so, given that the latter has little in common with the former two either on narrative, thematic, or formal terms.

Von Trier’s work took a dramatic shift with the release of Antichrist, evolving from the style deployed in most of his work from Breaking the Waves to his 2006 deconstruction of the workplace comedy The Boss of It All. Whereas handheld cameras that follow the action, camcorder grain, improvisational acting, and unpolished editing permeated his features during this period, Antichrist draws heavy influence from German Romanticism and the operatic music of Richard Wagner to define the setting and visual techniques throughout. Shot in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia for its primal look, von Trier developed Antichrist’s visual schema in part from the video game Silent Hill but also the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, the German painter whose landscapes often contain a fantastical austerity. Von Trier translates this to film through his newfound interest in the technical and traditionally beautiful methods of filmmaking, from deploying an overture to adopting slow motion and horrific beauty to confront the Wagnerian view of Nature as the Kantian sublime. The film considers Nature as Satan’s purview, a kind of anti-Eden inspired by the horror and ecstasy found in the art of Hieronymus Bosch.

Many of these stylistic qualities carried over to von Trier’s execution of Melancholia—the second in what critics, scholars, and cinephiles have deemed von Trier’s Depression Trilogy, made over four years to address his struggle with clinical depression in the mid to late 2000s. He started the trilogy with Antichrist, which used the filmmaker’s condition as part of its publicity, describing the result as an unfiltered look at his creative, depressive impulses. Melancholia came next in 2011, followed by Nymphomaniac, released in two parts in 2013. But the trilogy designation is an invention of the media, both social and professional. When Badley asked him about the notion, von Trier merely laughed and remarked that he’s dealt with depression most of his life, so the framing of a trilogy “could fit all my films.” Moreover, viewing any of these three films—or any selection from von Trier’s filmography—through the lens of depression limits its scope. Even so, von Trier and Badley have both suggested that Antichrist and Melancholia remain connected in a “duology” by the theme of depression. By contrast, Nymphomaniac and his subsequent feature, The House That Jack Built (2018), were likewise connected in von Trier’s intent to get away from the kind of accessible methods deployed in Melancholia—from its sci-fi conceit to its more classical visual approach compared to the director’s other films—with a mode he called “Digressionism.”

The style of Melancholia that later displeased von Trier so—enough to prompt a Digressionist movement away from that aesthetic with Nymphomaniac and The House That Jack Built—employs a grandeur from the German concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” which finds harmony between drama, theme, cinema, music, painting, landscape design, and architecture. The film adheres to distinctly German classicism, rooted in Wagnerian music and visual themes, references to classical painting, and images that von Trier refers to as “monumental.” The director regularly draws from a wide range of influences, including German expressionism, Italian Neorealism, New German Cinema, Stanley Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky, David Lynch, Karl Marx, Franz Kafka, and American history. He’s also often compared to other Nordic filmmakers, from the poetic austerity of Carl Th. Dreyer to a concentration on anguished female characters found in Ingmar Bergman. In this sense, von Trier’s work converses with other filmmakers, artists, and literary minds across time. Melancholia is no exception, speaking to Wagner’s operatic grandiosity, Henrik Ibsen’s chamber dramas, and Bergman’s portraits of women wrought by depression, all within a Twilight Zone container.

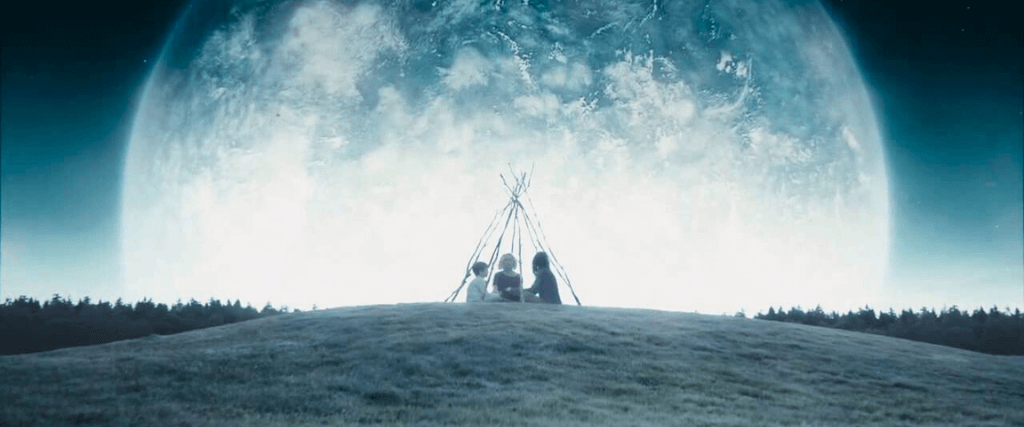

The film unfolds in two sections, preceded by a prologue set to the Tristan and Isolde prelude. Beginning with the opening images of an expressionless Justine amid falling birds, Melancholia parades a rhapsodic procession of monumental images, shot by cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro (Nymphomaniac, The House That Jack Built) in ultra-slow-motion using a Phantom camera that captures 5,000 frames per second. Each successive image is an orphic projection of Justine’s vision of things to come: Melancholia eclipses the red star Antares from the Scorpio constellation, and then it passes frighteningly close to Earth in a so-called flyby before finally returning to collide. Justine’s sister Claire races with her son Leo (Cameron Spurr) out across a golf course, her footsteps penetrating the green, which slows her down. A horse falls in a field while the aurora borealis shimmers in the background. Butterflies rise from the ground around Justine, and electricity sparks at her fingers. Gray yarn wrapped around Justine and the surrounding trees prevents her from moving forward. She then appears in a stream in her wedding dress. And just before the Earth is demolished by Melancholia, Justine and Leo prepare a makeshift shelter out of sticks—a “magic cave” that will protect them. Versions of the prelude’s monumental images will occur in the subsequent two parts in either literal or metaphoric terms.

Next, the film proper begins with “Part One: Justine,” which follows in the tradition of European cinema that satirizes the decadent class through an elaborate party, recalling Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939) in its hedonism; Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte (1961) in its alienation; and The Celebration (1998), made by von Trier’s Dogme 95 compatriot Thomas Vinterberg, in its almost farcical portraiture of the upper class. Justine and her new husband, Michael (Alexander Skarsgård), arrive unfashionably late to their wedding reception, their stretch limo unable to navigate the winding driveway that leads to Claire and her husband John’s (Kiefer Sutherland) mansion estate. Ever annoyed, John reminds them how much he’s spending to give them a reception and then warns Justine, “You better be goddamn happy. Do you have any idea how much this cost me?” The pressure to be happy, only to not feel that way, triggers Justine. As does Gaby, Claire and Justine’s vitriolic mother, played by Charlotte Rampling, who refuses to endorse any marriage, much less her daughter’s. Their father, Dexter (John Hurt), receives the event with blissful games, such as stealing cutlery and making a general spectacle of himself. Justine’s boss, Jack (Stellan Skarsgård), also attends, announcing her promotion to art director and tasking a new employee, Tim (Brady Corbet), with getting Justine to provide a tagline for a new campaign before the night is through. All the while, the wedding planner (Udo Kier) shields his eyes from Justine, personally offended that she has disrupted his precise schedule.

In sharp contrast to the prelude, Part One derives its look from what Badley describes as “documentary naturalism and an expressionistic experimentalism”—Dogme 95-style scenes to instill a dramatic immediacy. In that respect, Melancholia’s first half has more in common visually with von Trier’s other films set in America, such as Dogville and Manderlay, where the handheld camerawork follows the action and the editing features jump cuts and abrupt edges. The style reflects Justine’s agitated presence in her surroundings of conspicuous wealth, including an eighteen-hole golf course and a lavish estate. Never have von Trier’s characters come from such wealth or had such beauty surrounding them during their misery, and the location seems to remark on America’s capitalist empire heading towards destruction. The implication is that the excesses of American capitalism and neocolonialization into globalization will, in time, be reduced to nothing, returning to the space dust from which we originated. With this foreknowledge, Justine, a self-proclaimed prognosticator, has too much and it weighs on her—a notion visualized in the prelude image where gray fabric stalls her progress. This wealth is a reminder that she cannot force happiness with riches or the pleasantries that surround her; rather, its oppressiveness represents a commitment and obligation to be happy that she cannot fulfill. Soon, Justine spirals downward, disappearing from the reception for long periods, even having sex with Tim on the golf course in a self-destructive impulse to sabotage her marriage, and successfully so—when the night is through, Michael leaves her. Justine can only ask, “What did you expect?”

In “Part Two: Claire,” Justine’s sister begins composed and attempts to maintain her nurturing, motherly figure evidenced throughout Part One. But she gradually breaks down in the face of impending doom while Justine achieves a calm. Although Melancholia’s approach worries Claire, John remains confident that the planet will behave as the scientists claim: by flying by Earth without a collision. But when the planet passes, only to return suddenly for the final blow, Claire spirals, particularly after finding that her husband has ended his life with her reserve pills. From here, the sisters switch roles as nurturer and dependent in Part Two, recalling a similar change in Bergman’s Persona (1966). Though Claire remains incapable of consoling her son, Justine finds her stride as a Cassandra figure faced with overwhelming despair. Her ability to “know things,” such as humanity’s solitude in the universe, gives her an eerie peace and satisfaction. “The Earth is evil,” Justine remarks, adding, “No one should grieve for it.” For Justine, the world is one big anthropogenic nightmare, compelled by humanity’s selfish disruption of the planetary ecosystem. Claire and John’s excesses are a symptom of the Earth’s malady, so Justine welcomes Melancholia, even if it means destroying her loved ones. The world’s destruction is a corrective measure and a release valve for Justine, who sees The End as justification for feeling hopeless. Even so, she helps her nephew Leo prepare a “magic cave,” the skeletal frame of a tipi, to calm him before their destruction.

Doubtless, von Trier’s setup took some inspiration from Albrecht Dürer’s engraving, Melancholia I (1514), featuring an angelic figure gloomily regarding a celestial body emerging from clouds in the distance. More than most of von Trier’s work, Melancholia features sundry influences ranging from Pre-Raphaelite painting to European arthouse cinema. But Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde remains the film’s central leitmotif. In interviews upon the film’s release, the director noted how the choice to use Wagner stemmed from Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, which features a lengthy discussion about the all-time greatest work of art. Proust settles on Tristan and Isolde’s overture, which inspired von Trier’s choice to underscore his monumental imagery with Wagner’s music. The director’s work alongside editor Molly Marlene Stensgaard, too, is determined by beats in the piece, adding to the film’s form-follows-function construction as a “total work of art.” However, cutting on beat with Wagner was a “vulgar” practice, von Trier told interviewer Per Juul Carlsen, comparing the technique to an orderly Nazi aesthetic of logical edits and tableau-like sequences that interested von Trier during the film’s production. Much has been written about Melancholia’s assemblage and its German aesthetic qualities, yet, despite the predominance of Wagner, von Trier makes many other allusions in the film.

Consider how von Trier showcases paintings similarly to Tarkovsky, who habitually used paintings to reflect a film’s themes. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow (1565), heavily referenced in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), also appears in Melancholia, achieving an effect that seems more dependent on Tarkovsky’s use of Bruegel than on Bruegel alone. John Everett Millais’ painting Ophelia (1851-52), inspired by a scene alluded to, but not shown, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where Ophelia floats in a river before drowning, also plays a significant role. The distributor at Magnolia Pictures used the image in Melancholia’s publicity and, along with the music, it imbues the film with an emotional scale echoed by its monumental visuals and aural majesty. Similarly, when Justine lies naked near a stream at night, basking in the eerie blue twilight of “enriched darkness” from the approaching planet, as though offering herself to whatever’s coming, von Trier based the image on the Norse myth of Ragnarök popularized in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods, 1876), foretelling the end of everything. Another reference to Norse mythology occurs when Justine and Claire go horseback riding. Justine’s beloved horse Abraham refuses to cross a bridge, possibly representative of the Bifröst, the rainbow bridge Norse gods cross to enter Valhalla. But Justine cannot cross, suggesting her existence on the earthly plane.

Besides classical influences, von Trier often employs traditional mainstream genres in his films—horror, detective fiction, wartime drama, farcical comedy, melodrama—and uses them to antagonize Hollywood standards. Melancholia blends highbrow sources (Wagner, Shakespeare, Bergman, et al.) with the lowest form of spectacle, the disaster movie, most synonymously with the output of world-destroyer Roland Emmerich’s various CGI extravaganzas: The Day After Tomorrow (2004), 2012 (2009), and Moonfall (2022), to name just a few. A more specific inspiration may have been Rudolph Maté’s When Worlds Collide (1951), about a rogue planet and star—spotted in the Scorpio constellation, similarly to Melancholia—both on a course with Earth. Maté’s film opens with a reference to the Bible and God punishing all those on Earth for their corruption and violence, echoing Justine’s analogous belief that humanity deserves what’s coming. Susan Sontag wrote that disaster movies are “weak just where the science fiction novels (some of them), are strong—on science.” To be sure, von Trier’s film is not concerned with scientific accuracy regarding its rogue planet. Instead, the film is a “sensuous elaboration,” in Sontag’s terms, about “the fantasy of living through one’s own death and more, the death of cities, the destruction of humanity itself.” But while most disaster movies rely on thrills and action to maintain their audience, von Trier’s version of a disaster movie concerns dread and allegory, foregoing many of the customary escapist pleasures of popcorn cinema.

In von Trier’s hands, the sci-fi disaster foundation disrupts the social and behavioral realism on display, shattering the physical world with unearthly light and phenomena that upset the natural order. Von Trier’s planetary images also harken to the alignments from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), offering spectacular images worthy of Wagner’s music and tied to the characters in symbolic terms. Furthermore, the film’s setting resists the typical environs of a disaster movie; instead, they limit the action to a vast and serene estate, straight out of Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961). Von Trier shot the exteriors of Melancholia around Tjolöholm Castle in Halland, Sweden, a site designed from globalized artistic sources, including an Elizabethan façade, Tudor designs, and Gothic architecture. Given its sources, the castle is a synecdoche of the film and von Tier’s artistic agenda, with its array of influences merging into a wholly modern and original structure. These dynamics incited Badley to describe the film as “an experimental work of cinematic art in which aesthetics and affect predominate over plot; score and image over narrative.”

Melancholia’s status as a Gesamtkunstwerk within a Hollywood genre feels less rebellious or turbulent on von Trier’s part than the conceits behind The Idiots, Dogville, and Antichrist. The lack of transgressive imagery, shock value, and provocation next to his other films led to the director decrying its operatic presentation. “‘Melancholia’ is the least naughty film I ever did,” he told Carlsen. “I may have made a film I don’t like […] It consists of a lot of over-the-top clichés and an aesthetic that I would distance myself from under any other circumstances.” His disdain for Melancholia would ultimately stem from its perceived conventionality next to his previous work. “I’m usually madly in love with everything I do,” he told Carlsen. “I’m probably the most self-satisfied director you’ll ever meet. But this film is perilously close to the aesthetic of American mainstream films. The only redeeming factor about it, you might say, is that the world ends.” However, von Trier takes his film’s rich intertextuality for granted. Although von Trier at once immerses the viewer in a Gesamtkunstwerk, he also distances them through the constant negotiation of his many allusions throughout to Wagner, Bergman, Tarkovsky, Dürer, Millais, and Resnais, which, along with the production’s conspicuous beauty and sublimity, serve as Brechtian flourishes. To whatever degree von Trier despises the outcome, his efforts on Melancholia remain among his most visually powerful, referentially complex, and emotionally gut-wrenching.

The film is also typical of von Trier in that it features a powerful central performance by his lead actress, a trait he consciously borrows from Dreyer, who often made films about women. If von Trier’s heroines too often suffer and become martyrs, Melancholia presents two sisters who remain strong in their ways. Dunst gave a career-best performance and earned the Best Actress Award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011. A former child performer whose transition into adult roles saw no end of impressive work and personal struggle, Dunst was open about identifying with Justine, whom she embodies with blank eyes, a wounded posture, and a vacant face, which reflect von Trier’s depression but also Dunst’s. In 2008, she attended the Cirque Lodge for rehab after a stint with depression. She told British ELLE, “I am very much portraying Lars’s experience of depression, [but] I brought my own slant [to the role].” She continued, “We met before I did the movie and talked about how the light goes out of your eyes. People don’t talk about depression, so for me it was really amazing that this was going to be portrayed.” Nevertheless, von Trier and his team went to great lengths to avoid hinting at typical diagnoses for Justine’s behavior, resisting conventional explanations or suggestions of past trauma to allow for a specific, wholly valid portrayal of both the director and star’s experiences. The film never mentions Justine’s condition; rather, depression is implied through Justine’s behavior and worldview.

Given what journalist John Rockwell called the “charged aura of evil that hangs over Wagner since the Holocaust,” von Trier received questions about his influences during the film’s debut at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011. Melancholia’s main competition at the festival was Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, another ambitious and spatial search for meaning, which would go on to win the Palme d’Or. But the notorious press conference for von Trier’s film is often blamed for Melancholia not winning the top prize. There, his provocateur mode was in full effect, making lewd references to his next film as a work of hardcore pornography and quipping that, as someone who once thought he was a Jew and later learned he’s German, he understands Hitler. Although made in tasteless, self-mocking jest, his rambling remarks were the mutterings of a director trying to make a point about his film and his artistic perspective. But he did so with a typical strategy—by prodding journalists with controversial remarks without thinking out his statement beforehand. Besides distracting from the film, the viral soundbite earned him the status of “persona non grata” from the festival. Jury member Olivier Assayas has since confirmed that most of the jury under president Robert De Niro had favored von Trier’s film over he Tree of Life. Still, after the press conference, which has become one of the festival’s most talked-about moments, they went with Malick’s film to protest von Trier’s behavior. Regardless, Melancholia’s generally rhapsodic reception proved frustrating to the filmmaker, who prides himself on walkouts and regards good press as a bad sign.

In the years since von Trier’s behavior overshadowed his film, Melancholia has emerged, like a planet hiding behind the Sun, to produce a feeling of cinematic ecstasy in its rapturous images and penetrating emotions. Unlike most of his work in his late-career period, von Trier gets out of his own way here, allowing himself to acknowledge his depression and confront the matter in ways that resonate emotionally and artistically. Save for his extratextual antics, the film remains among his most aesthetically layered and profoundly moving, forcing his audience to identify with the cathartic release of everything through the world’s destruction. The empathy that Justine finds for Claire and Leo, guiding them through The End in her nephew’s “magic cave,” is proportionate to the understanding von Trier establishes for her depression. For all of von Trier’s allusionism and postmodern blending of various influences into a “total work of art,” his film talks about depression—albeit without talking about depression—in a manner few films have. Von Trier doesn’t make Melancholia about himself, despite its origins; he employs his intellectual exactness, coarse humor, and multifaceted aesthetic in service of his themes, not himself. However, different from his other work and marked by a singular timelessness, it’s possibly his most emotive and beautiful film.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Dave. Thank you for your continued support and friendship, Dave!)

Bibliography:

Björkman, Stig. Trier on Von Trier. Trans., Neil Smith. Faber and Faber, 2005.

Carlsen, Per Juul. “The Only Redeeming Factor is the World Ending.” The Danish Film Institute, 4 May 2011. https://www.dfi.dk/en/english/only-redeeming-factor-world-ending#:~:text=INTERVIEW.,the%20end%20of%20the%20world. Accessed 26 January 2024.

Cheung, Lucy. “Interview: Lars von Trier: ‘I’ve started drinking again, so I can work.’” The Guardian, 20 April 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/apr/20/lars-von-trier-interview. Accessed 21 January 2024.

Elsaesser, Thomas. European Cinema and Continental Philosophy: Film as Thought Experiment. Bloomsbury, 2019.

Eshelman, Raoul. “Performatism in Art.” Anthropoetics XIII, no. 3 Fall 2007/Winter 2008.

Figlerowicz, Marta. “Comedy of Abandon: Lars von Trier’s Melancholia.” Film Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 4, 2012, pp. 21–26. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.65.4.21. Accessed 1 February 2024.

Hill, Derek. Charlie Kaufman and Hollywood’s Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers: An Excursion Into the American New Wave. Kamera Books, 2008.

“Kirsten Dunst Talks Rehab, Depression To British ELLE.” Huffington Post, 2 August 2011. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/kirsten-dunst-talks-rehab_n_915931. Accessed 25 January 2011.

Larkin, David. “‘Indulging in Romance with Wagner’: Tristan in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (2011).” Music and the Moving Image, vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, pp. 38–58. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5406/musimoviimag.9.1.0038. Accessed 1 February 2024.

Peterson, Christopher. “The Magic Cave of Allegory: Lars von Trier’s Melancholia.” Discourse, vol. 35, no. 3, 2013, pp. 400–22. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.13110/discourse.35.3.0400. Accessed 2 February 2024.

Rockwell, John. “Von Trier and Wagner, a Bond Sealed in Emotion.” The New York Times, 8 April 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/08/movies/film-von-trier-and-wagner-a-bond-sealed-in-emotion.html. Accessed 25 January 2024.

Schepelern, Peter. “The Making of an Auteur: Not on the Auteur Theory and Lars von Trier.” Visual Authorship: Creativity and Intentionality in Media. Ed. Torben Godal, et al. University of Copenhagen, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2005, pp. 103-127.

Simons, Jan. Playing the Waves: Lars Von Trier’s Game Cinema. Amsterdam University Press, 2007.

Sontag, Susan. “The Imagination of Disaster,” Commentary, October 1965, pp. 44-48.

Stevenson, Jack. Lars von Trier. World Directors. British Film Institute, 2002.

“Tranceformer—A Portrait of Lars von Trier.” Directed by Stig Björkman, 1997. Lars von Trier’s E-Trilogy. Tartan, 2005. DVD.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review