The Definitives

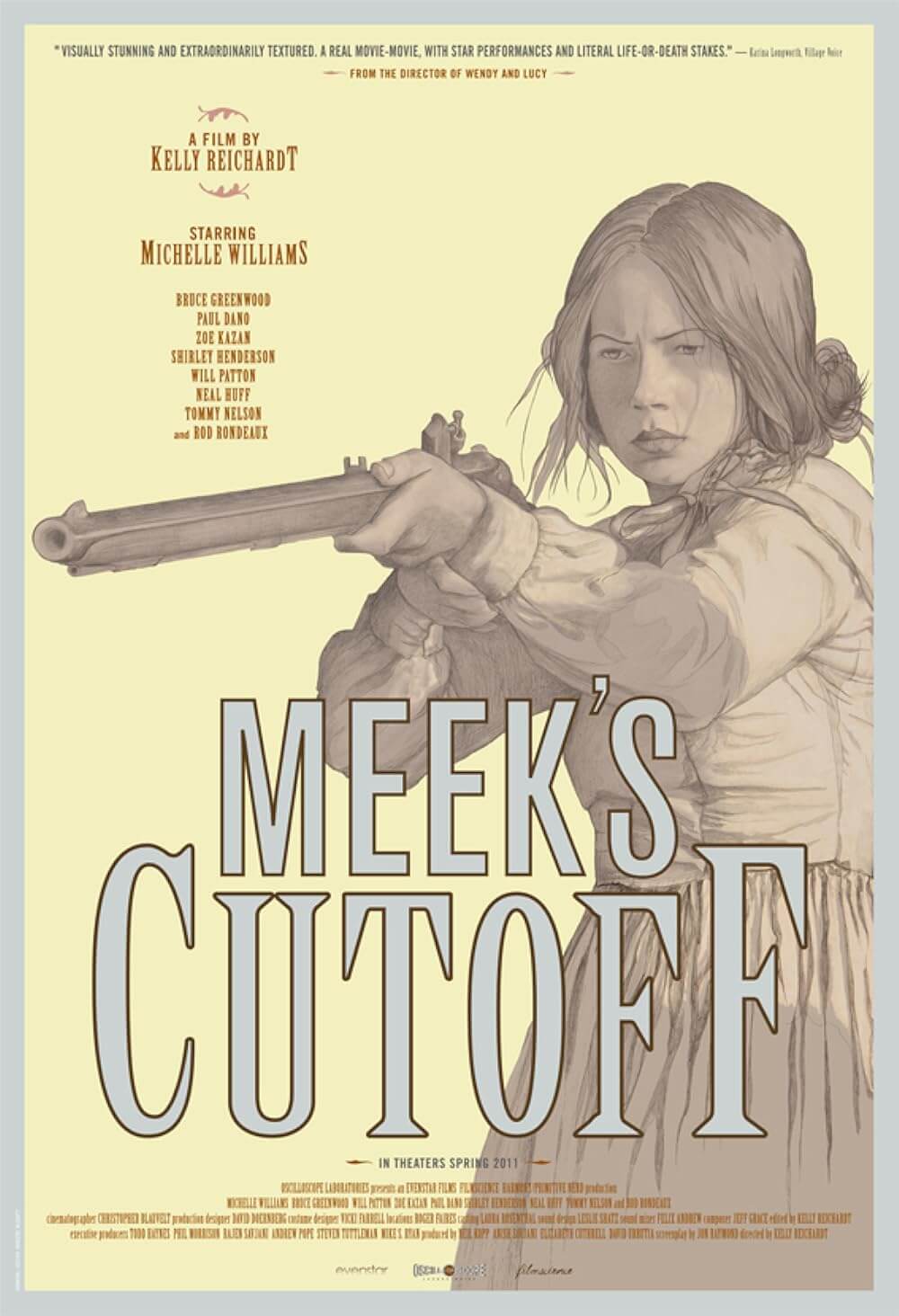

Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

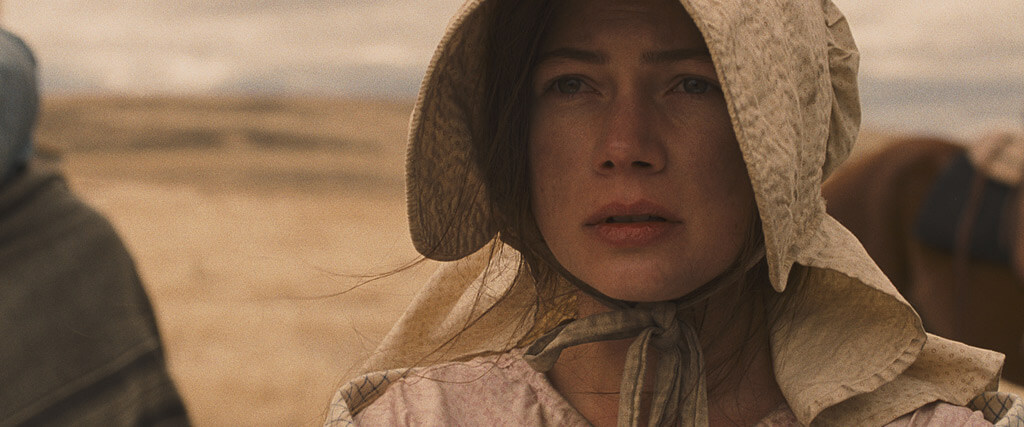

Kelly Reichardt’s films focus on the searching, inward experiences of her characters. But none more so than her first true Western, Meek’s Cutoff, whose theme is etched in the opening shots. One of seven settlers bound for the West carves “LOST” into a dried-out fallen tree, and therein, he engraves Reichardt’s subversion of the most American genre. The conventional Western reassures moral convictions against an untamable wilderness, whereas Reichardt concentrates on unromantic tasks, avoids defining her characters through easily recognizable tropes, and resists narrative closure. She embraces the rhythm of everyday activities, from the tedium of travel to simple, menial tasks and processes, and her approach forgoes Western standards, such as rowdy chases, heroes and villains, and shootouts. Instead, Reichardt uses long takes and intentionally paced shots of a meandering voyage to Oregon, which replace the majesty and masculinity of the Western with something alternative. The film’s perspective is unquestionably feminist, though never polemical in how it depicts the lack of power among nineteenth-century frontier women. Drawing from an actual event, Meek’s Cutoff concerns itself with an austere and natural portrait of reality. Reichardt explores, through her exacted narrative and form, a feeling of emotional isolation that emerges when confronted by a patriarchal community’s false sense of security. Her willingness to question the certainty of masculine Westerns also supplies an investigation of reality, our incomplete view of it, and the limits of true knowledge, resulting in a haunting film about people finally resigning themselves to the chaos of the universe.

The film takes its name from the Oregon Trail shortcut, the Meek Cutoff, a route known primarily for the Lost Wagon Train of 1845. Histories and diaries from the time recount real-life fur trapper and frontiersman Stephen Meek, who led a party of over 1,000 settlers in some 200 covered wagons, driving several thousand head of cattle across a seemingly more direct route to the Promised Land. Meek claimed the alternate path, then untested by any wagon train, would save them 150 miles. From Fort Boise, Meek would take the party over the Blue Mountains and then deliver them straight into the Willamette Valley. The proposition sounded appealing since many feared the widespread reports of Cayuse tribe attacks on the main Oregon Trail. But after clearing the mountains, the train became aware that Meek did not recognize the territory, today known as the Oregon High Desert. Having trapped there a decade earlier, Meek remembered lakes; unbeknownst to him, they had since dried up in the droughts. Unsure where to go, he sent out scouts who came back with no clear direction to salvation. With grass and water in short supply, the emigrants and their livestock suffered. After some disputes in the camp, the group split into two parties, one following Meek, and the other taking an alternate route. Though the train eventually came back together farther down the trail, twenty-three people died along the way. Many blamed Meek for their losses. To paraphrase the diary of one survivor, it was a bad cutoff for all that took it.

Reichardt provides no exposition to establish the events in her film besides the immediate setting, Oregon in 1845, communicated by a single title card. Everything else must be gleaned through observation; even the dialogue is barely heard over the sounds of Conestoga wagons plodding along through barren country. Three couples head westward across punishing terrain, shepherded by their grizzled guide, Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood), an almost comical braggart wrapped in tasseled leather and chock full of tall tales about his adventures taming the Wild West. What we know about the families comes from their present journey; the film offers no backstories. Though each has their own wagon and livestock, the settlers support each other with food, water, and effort, toiling to cross rivers and carefully navigating their fragile wagons down steep hills. The God-fearing couple of William White (Neal Huff) and his pregnant wife Glory (Shirley Henderson) have brought along the only child on the journey, the adolescent Jimmy (Tommy Nelson). Thomas Gately (Paul Dano) and his fearful wife Millie (Zoe Kazan) worry about the dangers of continuing forward, despite their adrift guide. Reichardt aligns the film’s perspective with the group’s most sensible pair, Solomon Tetherow (Will Patton), a logical and well-reasoned man whose new young wife, Emily (Michelle Williams), is resourceful and, increasingly, outspoken. “We should never have left the main stem,” Emily says, regretting the decision to follow Meek’s shortcut.

If Meek’s Cutoff offers thin characterizations for its settlers, it could be that Meek, an excessive windbag, has consumed the air around them. Reichardt situates her characters in response to Meek. The settlers watch him from behind, leading the train, though he’s unsure of their exact location and does not know when they will find water again. Reichardt’s camera often adopts the women’s perspective, Emily above all, and observes Meek’s endless swagger with a critical eye. Meek is a monumental blowhard, a personality suited for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, a larger-than-life figure desperate to validate himself by spinning yarns about his legendary heroism and experience. He might also be a symbol of John Ford’s Western—someone who wholeheartedly believes the maxim of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962): “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Ever chattering about his exploits, he is committed to his own legend. He has invented it. His world is comprised of masculine heroism and a blustering ego, like one of John Wayne’s characters, or Wayne himself, in his arrogant self-certainty. He claims to be a gallant killer of Indians and boasts of his oneness with Nature (“I live with this world, not just in it”), and somehow, his confidence persists despite admitting he’s lost. By contrast, the other men in the party remain passive, following Meek on the train, unwilling to confront his authority as their guide or follow Emily’s growing dissent. Further down the line, Emily walks and listens to Meek telling his stories to Jimmy, stories only a child could believe.

Meek’s Cutoff is structured around the journey, a repetition that follows Meek’s lead by day and camps in the pitch-blackness at night. The dynamic changes when a Native American man (Rod Rondeaux) from the Cayuse tribe appears before Emily as she gathers firewood. The Indian, as he is credited, scatters, while Emily rushes back to signal the others, loading a musket and firing into the sky in a scene that shows she can handle a gun. Meek and Solomon resolve to track down the Indian and return him to camp as their prisoner, and his presence amplifies the personalities of everyone in the wagon train. Meek wants to kill him, arguing that other Cayuse will surely follow. Meanwhile, Millie’s crippling terror of his Otherness is doubtless magnified by Meek’s horror stories. “You know what I’ve seen this heathen’s brothers do? I’ve seen ‘em strip the flesh off a man while he’s still breathin’,” he warns in grandiose fashion. “I’ve seen ‘em cut a man’s eyelids off and bury him in the sand and leave him just starin’ at the sun.” Far more rational, Solomon and Emily want the Indian to lead them to water, as he must be familiar with the territory. Emily, in her prudence, recognizes that, even though they have taken him prisoner and he does not speak English, her kindness may be returned for their salvation. She fixes the Indian’s shoe and explains her shrewdness, “I want him to owe me something.” The Tetherows convince their fellow emigrants to let the Indian lead them to water, and Meek is outvoted. But will their new guide lead them to water or into a deadly trap? The film’s open-ended conclusion preserves that question.

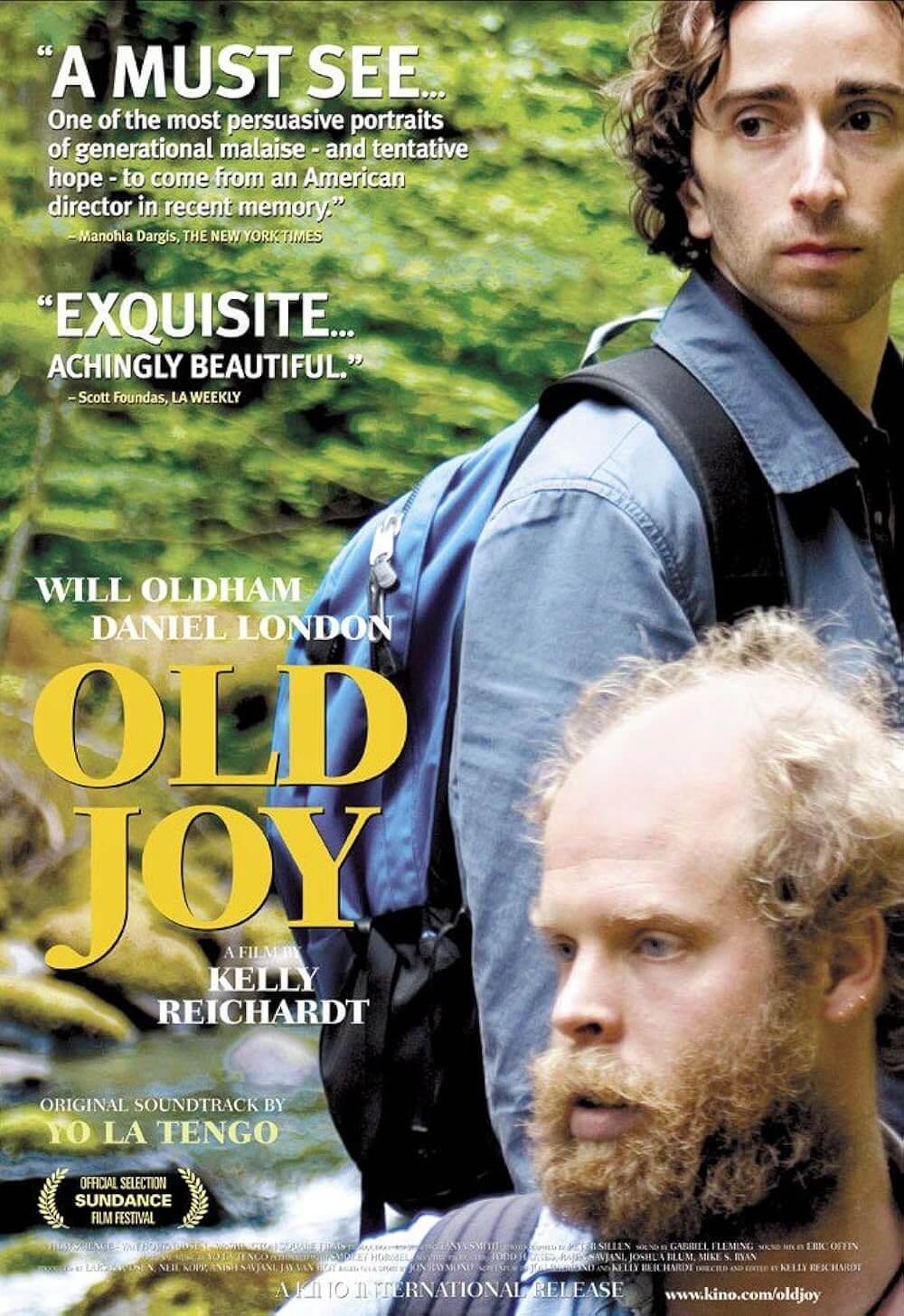

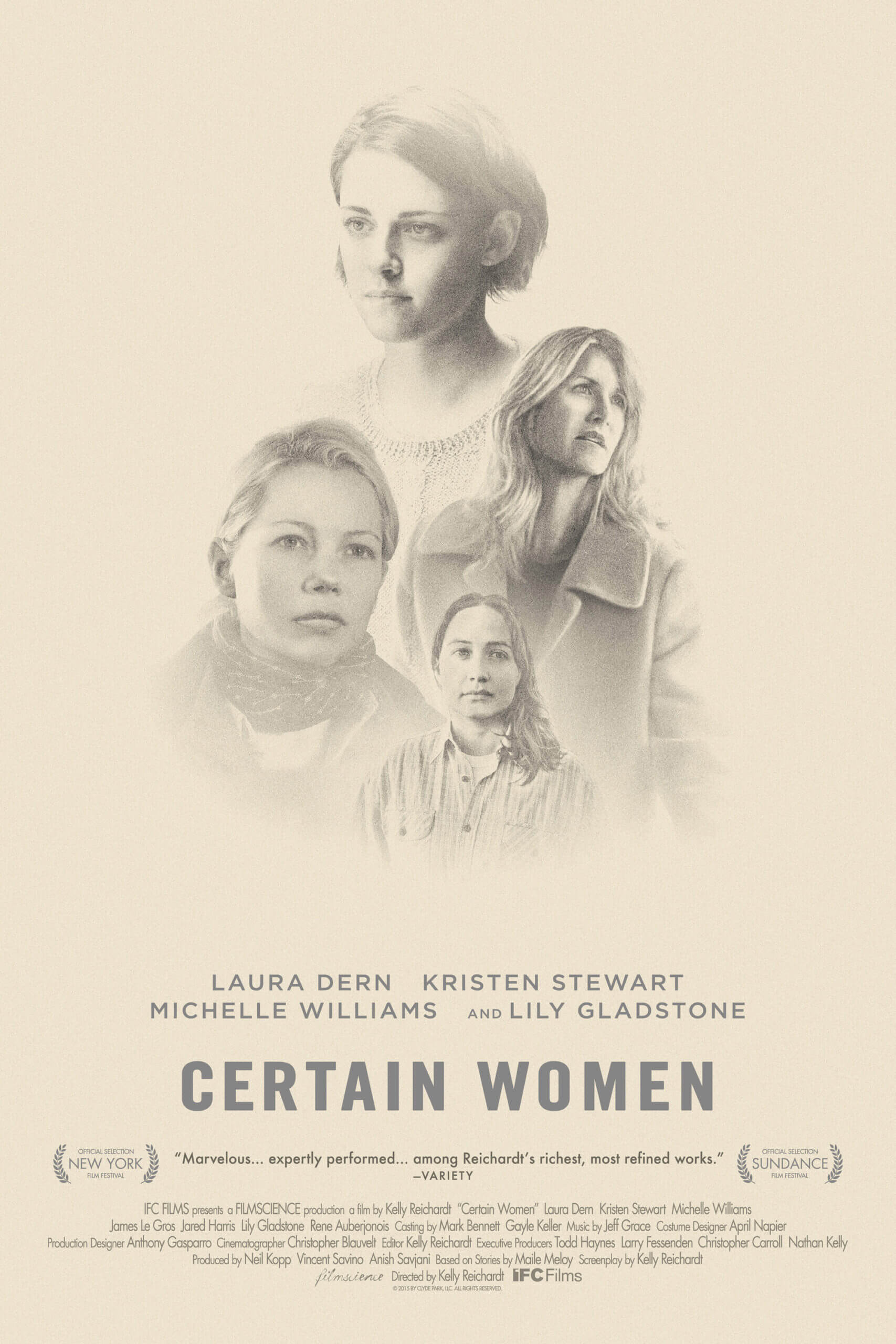

Reichardt’s minimalism informs her narrative and visual style, from the equivocal last shot in Meek’s Cutoff to the protracted takes and even longer silences during the emigrants’ journey. In a relatively short period of time, Reichardt has made a name for herself in sparse cinema—microbudget independent productions whose subjects are resigned to mutable roles. Reichardt’s characters often subsist in a repressive environment, hesitant to speak or articulate their inner selves, prompting her audience to investigate her characters through their own projections. It’s tempting to call her perspective an exclusively feminist one, given that her protagonists are usually women, but she examines the same qualities among men as well. Her second film, Old Joy (2004), the story of two college friends on an overnight camping trip to a hot spring, their uneven impressions of their friendship, and their various insecurities, captures masculine relationships better than any picture of the twenty-first century. After her debut film, River of Grass (1994), which is set in her native Florida and follows an aimless couple on a crime spree, she shot experimental short films and attempted to develop another feature. But her breakthrough with Old Joy led to a wealth of output—Wendy and Lucy (2008), Night Moves (2013), Certain Women (2016), First Cow (2020). And with each new film, her cinema has defined her stripped-down and opaque aesthetic, leaving her audience to search for meaning.

Writer Jonathan Raymond supplied the short stories on which Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy were based; he also wrote the screenplays for those films, as well as Meek’s Cutoff and other, later films directed by Reichardt. The two were introduced in the early 2000s by their mutual friend, director Todd Haynes, who not only connected fellow Portland native Raymond with his first literary agent but executive produced nearly all of Reichardt’s films. Both Reichardt and Raymond find value in silences, where nonverbal emotional and psychological cues intensify and grow more complex from their wordless expression. This similarity in their approach enriches their collaboration, as Reichardt complements the implied feelings in Raymond’s writing through ruminative imagery. The idea for Meek’s Cutoff came when the two explored the Oregon High Desert while location scouting during the production of Wendy and Lucy. They were both drawn to the terrain, and Raymond later learned of Stephen Meek’s story. They began a research process that entailed visiting the many museum exhibits about the Meek expedition, reading the actual diaries of settlers that survive from the period, and books about the subject, such as Keith Clark and Lowell Tiller’s book Terrible Trail: The Meek Cutoff, 1845. Many of the events that occur in the film—such as the emigrants finding a nugget of gold that suggests a larger mine in the area, the location of which is lost to time—happened in real life. Although, Raymond’s screenplay scales down the actual event to three families under Meek’s guidance, partly out of necessity due to the film’s $2 million budget, but also because Reichardt gravitates toward intimate stories about a select few characters.

Writer Jonathan Raymond supplied the short stories on which Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy were based; he also wrote the screenplays for those films, as well as Meek’s Cutoff and other, later films directed by Reichardt. The two were introduced in the early 2000s by their mutual friend, director Todd Haynes, who not only connected fellow Portland native Raymond with his first literary agent but executive produced nearly all of Reichardt’s films. Both Reichardt and Raymond find value in silences, where nonverbal emotional and psychological cues intensify and grow more complex from their wordless expression. This similarity in their approach enriches their collaboration, as Reichardt complements the implied feelings in Raymond’s writing through ruminative imagery. The idea for Meek’s Cutoff came when the two explored the Oregon High Desert while location scouting during the production of Wendy and Lucy. They were both drawn to the terrain, and Raymond later learned of Stephen Meek’s story. They began a research process that entailed visiting the many museum exhibits about the Meek expedition, reading the actual diaries of settlers that survive from the period, and books about the subject, such as Keith Clark and Lowell Tiller’s book Terrible Trail: The Meek Cutoff, 1845. Many of the events that occur in the film—such as the emigrants finding a nugget of gold that suggests a larger mine in the area, the location of which is lost to time—happened in real life. Although, Raymond’s screenplay scales down the actual event to three families under Meek’s guidance, partly out of necessity due to the film’s $2 million budget, but also because Reichardt gravitates toward intimate stories about a select few characters.

Reichardt gives Meek’s Cutoff a distinct shape by experimenting with the 1.33:1 aspect ratio, the standard Academy ratio widely used in Hollywood until the emergence of widescreen formats in the 1950s. In recent decades, narrower ratios have made a comeback among many independent filmmakers such as Andrea Arnold (Fish Tank, 2009; Wuthering Heights, 2011; American Honey, 2016), Robert Eggers (The Witch, 2015; The Lighthouse, 2019), and Paul Schrader (First Reformed, 2018). These directors seem to use the ratio, or something close to it, as though today’s standard wide formats were a platform to work against, using the audience’s awareness of an older method and the unused option of widescreen to extratextual effect. Modern uses of this format often reflect the story’s period by adopting an outmoded look, represent a theme of confinement, or focus the viewer’s attention on characters within the prescribed frame. Reichardt’s work with the boxy frame in Meek’s Cutoff conveys several reactions at the same time. Cinematographer Chris Blauvelt, who has shot each of her films since Meek’s Cutoff, captures a scopic terrain despite the comparative lack of screen space by isolating characters or the entire wagon train within the frame, allowing the sky and rolling hills to drown out the settlers. Blauvelt echoes how the Academy ratio was used in Hollywood Westerns by John Ford, George Stevens, and Anthony Mann, filmmakers who captured unforgettable images from Monument Valley to the mountainous frontier of the Pacific Northwest, yet their work never felt circumscribed for lack of a panoramic view. At the same time, this visual seclusion in the never-ending landscape of Reichardt’s film intensifies the journey at hand, as if the characters proceed through a squarish tunnel. The ratio is at once immense and confining.

Reichardt’s use of the image reinforces the theme that the emigrants are prisoners in an open country. Many of her shots are stationary, as if mounted on a tripod and limited to panning right or left. When the camera moves, it does so to follow the steady progress of the wagon train. Never does she employ outwardly expressive angles or whooshing crane movements. Reichardt, serving as editor, also finds a transfixing quality in ultra-slow fade transitions between images that seem to blend together, as the figures in the forthcoming image look like ghosts passing through the previous scene. Elsewhere, Blauvelt shoots scenes in natural light, with night sequences lit only by campfires and lanterns, illuminating just a small portion of the frame. Reichardt emphasizes the use of light in several stark cuts from the pitch blackness of night to the penetrating daylight, causing the viewer to reflexively wince from the sudden switch. Behind every scene is a heightened ambient noise of the emigrants and livestock trudging along, and the persistent sound of a single squeaky wagon wheel. And though Jeff Grace has been credited with a score, only a few aching notes stretched along the last desperate minutes of the film break its many silences. Both visually and aurally, Reichardt adopts the transcendental quality of slow cinema, whose austerity forces its audience to think about the film while it unfolds, resulting in an alertness to every detail within the frame.

Reichardt told interviewer Leonard Quart that her focus was the “unheightened moment”—a stark and decidedly feminist contrast to the traditional Western’s expression of masculinity through its concentration on violence, victory, and moral certainty. Meek’s Cutoff certainty operates in a mode different than that of Ford’s similarly plotted Wagon Master (1950), another tale of settlers in a wagon train that, conversely, entails a romantic subplot, a shootout at the climax, and a finale in which the party arrives at their destination. Reichardt creates an alternative to her predecessors by limiting the first half of her film to the journey’s minutiae, drawing our attention to characters who would not usually have power or occupy the center of a traditional Western. She follows as Emily gathers firewood or prepares dinner; she sits with the women as they knit and hang laundry. Her gaze is feminine, watching from a distance as the menfolk stand in a circle, their voices overheard just enough to catch their deliberation about which way to go, none of them with an ounce of certainty. Reichardt’s initial interest in process, in the work of her women characters as the men make decisions about their route, occupies the feminine perspective, and through it, the viewer recognizes how the conventional Western, and to a greater extent nineteenth-century society, excludes women.

Reichardt told interviewer Leonard Quart that her focus was the “unheightened moment”—a stark and decidedly feminist contrast to the traditional Western’s expression of masculinity through its concentration on violence, victory, and moral certainty. Meek’s Cutoff certainty operates in a mode different than that of Ford’s similarly plotted Wagon Master (1950), another tale of settlers in a wagon train that, conversely, entails a romantic subplot, a shootout at the climax, and a finale in which the party arrives at their destination. Reichardt creates an alternative to her predecessors by limiting the first half of her film to the journey’s minutiae, drawing our attention to characters who would not usually have power or occupy the center of a traditional Western. She follows as Emily gathers firewood or prepares dinner; she sits with the women as they knit and hang laundry. Her gaze is feminine, watching from a distance as the menfolk stand in a circle, their voices overheard just enough to catch their deliberation about which way to go, none of them with an ounce of certainty. Reichardt’s initial interest in process, in the work of her women characters as the men make decisions about their route, occupies the feminine perspective, and through it, the viewer recognizes how the conventional Western, and to a greater extent nineteenth-century society, excludes women.

In considering Reichardt’s feminist perspective one cannot ignore the catalyst of Emily’s emergence as the protagonist, the character of Meek. Indeed, Meek’s Cutoff might be the ultimate film about a woman rallying against one man’s refusal to admit he needs directions. Their guide rationalizes, “We’re not lost; we’re just finding our way”—a statement that recalls Kurt (Will Oldham) in Old Joy, and his insistence that he knows just how to get to the hot springs, despite being lost. Reichardt’s films often feature lost characters, from the friends in Old Joy to the titular characters of Wendy and Lucy, who are not so much lost as sidelined in their journey. The state of being lost, either geographically or existentially, allows Reichardt’s minimalism to confront her characters in their ambiguous, unreliable, and amorphous worlds. It also allows each of her films to be interpreted as a kind of Western, as each explores unknown territory. Still, though Emily is resigned to a passive role in the train, she will not be led by a fool. “I don’t blame him for not knowing,” she whispers to Solomon. “I blame him for saying he did.” Emily’s growing frustration with Meek’s apparent ignorance and arrogance distinguishes her from the typical passivity of women in Westerns. She will not listen to Meek’s yarns about the dangerous Cayuse tribe; while others are rapt by his stories, she is unimpressed. “This meant to bring me over to somethin’?” she asks him flatly. Emily is too practical and resourceful to suffer Meek’s braggadocio, and she is also determined to prevent Meek’s execution of the Indian, the party’s one hope for salvation in her mind. In the climactic scene, when Meek draws his pistol with the intent to kill the Indian, Emily points the musket at him until he concedes and lowers his weapon, shifting the power dynamic of the train. By that time, though, Meek’s fearmongering has done its work.

The film transforms into a study of humanity’s reaction to fear and uncertainty, how for some even unlikely assurances are preferable to the terrifying emptiness of the unknown. Moreover, it contains a political undercurrent that reflects how certain figures retain their power. Meek tells dubious stories about his encounters with violent Native American tribes and warns of an imminent attack, stoking paranoia while building his own mythology as a survivor and authority. His methods recall political dictators who ensure devotion by spreading panic and then supplying themselves as the solution. Though, his idiocy prompts Emily to ask, in a question asked by millions living under a similar leader, “Is he ignorant or just plain evil?” In any case, Meek has successfully convinced Millie and others of their fate. “They’re almost here!” Millie cries out with terrible certainty—in a Chicken Little type Kazan would repeat in Joel and Ethan Coen’s Western anthology The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), though her fate is more certain in that film. And while most of the others agree that Meek’s stories have questionable merit, Reichardt nonetheless implants seeds of doubt in the viewer. Note how Millie keeps a bird in a cage for the journey that, like a canary in a gaseous coal mine, gradually dies over the course of the film, as if the settlers have entered poisonous territory. Millie also sees a conspiracy in rocks as the Indian leaves indecipherable symbols on a possible breadcrumb trail of stones, perhaps as part of his religion, perhaps as a message or signal to his tribe. Or notice the way the Indian subtly smiles when a wagon topples over, as if he’s pleased the emigrants have met with disaster. Are these true warning signs or coincidences that aid Meek’s role as a doomsayer?

Reichardt resolves to end Meek’s Cutoff with the inconclusiveness she sustains through the entire picture. She does not justify or disprove Meek’s prejudices, nor does she vindicate or condemn Emily’s decision to trust the Indian, and therein, she avoids the moral certainty associated with traditional Westerns. At the base of a hill, the wagon train arrives at a tree, indicating the presence of water nearby. Once the group follows the Indian over the hill, there’s a chance of finding water; there’s also the chance of an ambush waiting for them. The Pacific Northwest saw many deadly encounters with the Cayuse, including the Whitman Massacre of 1847 that left thirteen settlers dead. Meek resigns himself to Emily and Solomon’s lead. “I’m taking my orders from you now,” he tells them. “This was written long before we got here,” he adds, ever the believer in myth, especially his own, even if it means he is led to his death. But Reichardt refuses to give credence to his fateful last words in the film. It’s a structure that brings to mind the way humanity puts its faith in desperate ideas in Stephen King’s novella The Mist, where an isolated group of Maine townsfolk hole-up to avoid a monster-laden fog; some blindly follow an alarmist’s prophecy, others resolve to face the unknown’s infinite haze. A persistent theme of Meek’s Cutoff, then, questions where one places their trust and why. That Reichardt and Raymond chose to end their story on an open-ended note is a stark but telling contrast to the actual incident, where the wagon train splits into two parties and both find their way.

As scholars Katherine Fusco and Nicole Seymour have noted, the ambiguous ending also demonstrates how Meek’s Cutoff deviates from traditional and even revisionist Westerns in its withholding of Manifest Destiny. The white expansion and settlement of North America signals progress in classical Westerns from John Ford (Stagecoach, 1939), George Stevens (Shane, 1953), and William Wyler (The Big Country, 1958)—a bringing of order to the frontier’s untamed chaos. Revisionist Westerns from Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch, 1968), Clint Eastwood (Unforgiven, 1992), Jim Jarmusch (Dead Man, 1995), and Quentin Tarantino (The Hateful Eight, 2015) have questioned and portrayed the corrupting nature of white expansion, but they acknowledge its inevitability. Reichardt prefers to leave that destiny in question. It’s an idea symbolized when Meek argues that “women are created on the principle of chaos” in their ability to bring new life into the world, whereas men represent “cleansing, ordering, destruction.” Meek has firmly implanted himself in the ideals of Manifest Destiny, with its obliteration of Native American tribes and assimilation of the unknown into the familiar. In part, he sees the Indian, and all Native Americans, as chaos, given the man’s inability to speak English or submit to white rule; and it’s a significant detail that Reichardt does not supply the viewer with subtitles to translate the Indian’s native dialogue. Emily and Solomon have chosen a path that deviates from Westward expansionism; they resolve not to kill the Indian and choose to embrace the unknown rather than break it.

Meek’s Cutoff is unique in its revisionism for its essential ambiguity toward Manifest Destiny. Will Meek’s masculine order through destruction overcome Emily’s feminine chaos? Or does Meek’s theory represent an attempt at bringing order to the structureless world that Reichardt implies with her final shots? Emily watches as their Native American guide walks toward the horizon, and Reichardt fades to black before disclosing the party’s fate. Will the Indian find water or will he signal other Cayuse to attack? Is the answer right over the hill, or the hill after that? Considering how Meek’s Cutoff is put together, it becomes clear that Reichardt elicits internal responses that require the viewer to contemplate uncertainty itself. By refusing to answer questions about where the settlers’ journey ends, the film investigates what drives our fear of the unknown, as well as the costs of so-called civilization. Her method is elusive, contained in long silences, a lumbering journey, and spare, if beautiful, cinematography, along with a host of natural performances. But the approach is, in Meek’s terms, also unquestionably feminist in its willingness to embrace the chaos of ambiguity. In a film that places equal value on its omissions of sight and sound as the details it brings into sharp focus, it is unshakable in its demand to be revisited and reconsidered, but never resolved.

Bibliography:

Clark, Keith, and Lowell Tiller. Terrible Trail: The Meek Cutoff, 1845. Revised edition. Maverick Distributors, 1993.

Combs, Richard. “The Way West,” Film Comment, vol. 47, no. 2, 2011, pp. 30–33. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/43458764. Accessed 12 Jan. 2020.

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Hambleton, James H., and Theona J. Hambleton. Wood, Water & Grass: Meek Cutoff of 1845. Caxton Press, 2014.

Quart, Leonard, and Kelly Reichardt. “The Way West: A Feminist Perspective: An Interview with Kelly Reichardt.” Cinéaste, vol. 36, no. 2, 2011, pp. 40–42. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/41691003. Accessed 15 Jan. 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review