The Definitives

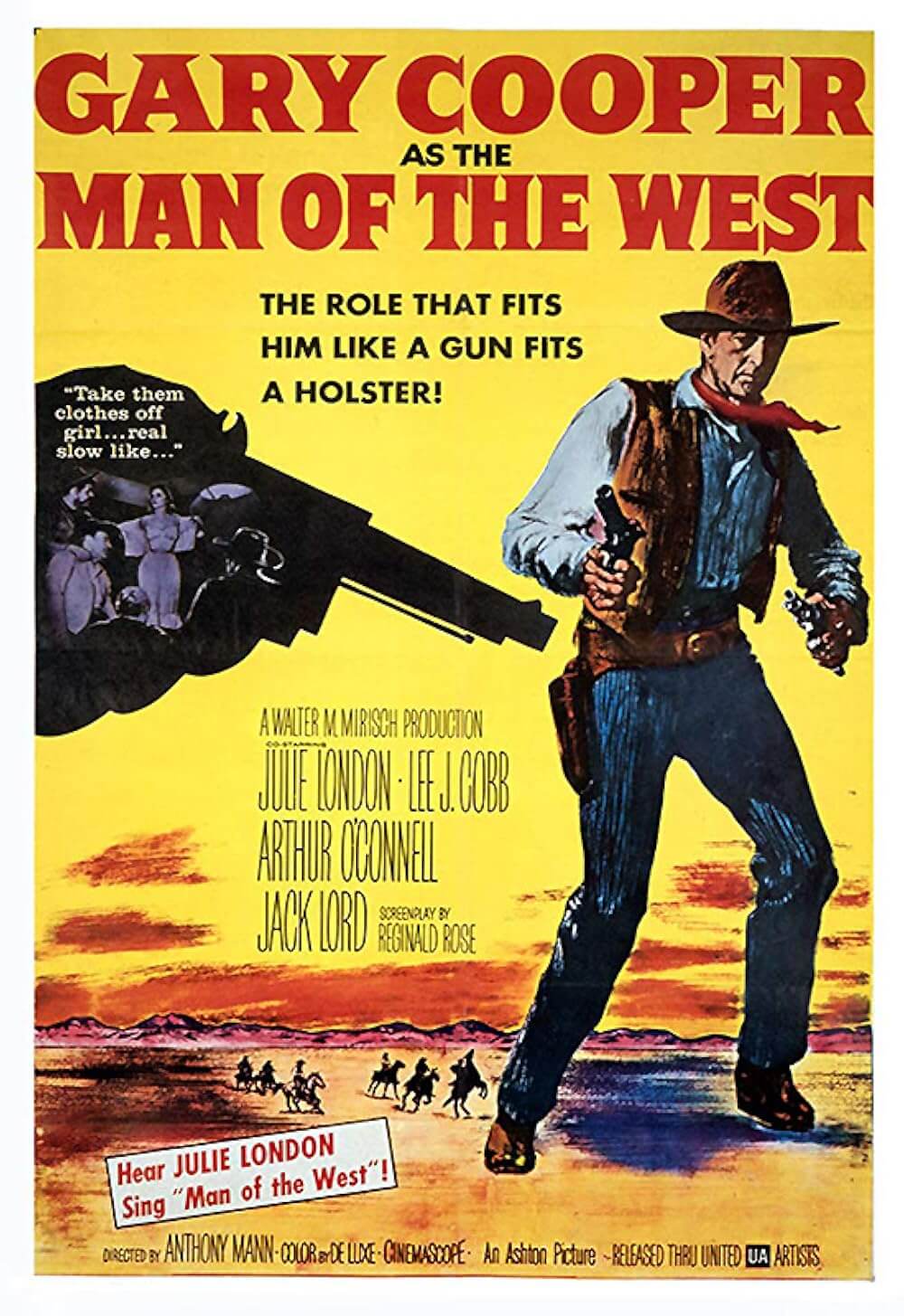

Man of the West (1958)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Anthony Mann made Westerns. He experimented in other genres, of course, honing his technical skills on atmospheric 1940s film noir pictures such as T-Men (1947) and Border Incident (1949) and dabbling in epics like El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) later in his career. But Mann’s skills were best applied to Westerns, the narrative model wherein character flaws are an engaging standard. The director filmed ten of the genre’s most rough-and-tumble titles between 1950 and 1960—The Furies (1950), Bend of the River (1952), The Naked Spur (1953), and The Man from Laramie (1955)—each one drawing unmistakably from the same cinematic themes and voice. Though perhaps not as popular or as commonly discussed as Ford or ever genre practitioners such as Raoul Walsh and Delmer Daves, Mann filmed the genre’s most purely cinematic achievements, yet remains an under-celebrated auteur. His masterpiece is Man of the West, a revolutionary 1958 film that establishes the dramatic turns of Western filmmaking over twenty or more successive years. Within this piercing tale of self-identity, the rugged persona of The Old West reaches brutal extremes and sheds away the illusory idealism established in Hollywood’s traditional Western films.

As challenging and as different as Mann’s stories are, they use basic moviemaking language to combine the two instruments of apparatus and narrative into one symphony, working together to project a rare expression of pure cinema. Some films rely wholly on story, some on their technical merits; Mann achieves a harmonious balance between the two, having learned from the best in his youth. Mann began in the theater, slowly working his way into Hollywood as an assistant director to Preston Sturges on Sullivan’s Travels (1941). Come the early 1940s, Mann was directing his own projects like Dr. Broadway and Moonlight in Havana (both in 1942) under the limitations of unforgivingly low-budgets, actors that could not act, and barely a set to stand on. Not until 1947 had Mann proven himself worthy to explore (now with ample resources) the depth soundly produced cinema could bring, specifically within the film noir genre. Working on highly stylized chiaroscuro crime pictures like Railroaded! (1947) and Raw Deal (1948) earned Mann a technical mastery used to intensify his project’s narrative center. His personal style sought to give the film meaning—but not through political or social commentary; rather, by pointing all formal tools in the same direction: delivering a devoted importance to raw storytelling.

By 1950, the year of his first Western release, a James Stewart treasure called Winchester ‘73, Mann had complete control over his abilities from both narrative and technical perspectives, and he would institute several story tropes that would appear throughout his decade-long Odyssey into the Western: His heroes and villains reveal close connections via familial or past association, though their worlds contrast in sometimes staggering, sometimes subtle degrees. His heroes usually seek criminal revenge against the villain for some offense, and thus are not prototypical good guys living life according to the law. Mann’s heroes survive by only one edict: the punishing psychological angst ordering them to commit (or hide from) outward violence. This inner conflict manifests through action, but also through the symbolism of the diminishing frontier wrought with criminality and violence. In an Anthony Mann film, there are no black and white distinctions between good and evil; there is only gray the internal struggle between the two.

By means of Jeanine Basinger’s seminal text Anthony Mann (decisive because her book was one of the first to explore the auteur theory so remarkably well, and also because no other text has penetrated so perceptively into Mann’s career since), we can see how three distinct levels to Mann’s Westerns arise: The literal narrative; a level of psychological symbolism where the landscape represents our hero’s conflict via metaphor; and an emotional level involving both the hero and audience. Basinger’s text simply outlines how Mann’s Westerns “present a story about a hero who is undergoing a psychological change.” In essence, Basinger tells how Mann’s films are applications of the cinematic process in an ideal form-follows-function architecture, where every instrument available (including script, location, camera movement, editing, use of space, and lighting) works to tell the best possible story. Mann’s Westerns are expert and proficient narratives without need for grand exegesis embedded inside subtext. In strategic, efficient terms, the apparatus is only employed to assist the narrative and the characters within it. Mann does not showboat or make his presence known as The Man Behind the Camera, nor do his films sell Anthony Mann as the product (or by-product). He was not Alfred Hitchcock. The audience is engulfed by Mann’s visceral stories from start to finish, without even a moment allowed in reprieve to appreciate his camerawork or adept management of his film’s technical elements. Indeed, Mann’s pictures are largely practical, achieving such functionality through a brilliant interplay of form and narrative rarely so uniform in Hollywood.

Man of the West begins like countless films in this genre, with a mysterious stranger arriving in a budding Western town. Named Link Jones and played by regular cowboy figure Gary Cooper, then in his late fifties, the outsider is tall and dignified. Few actors can personify the West so singularly—only those tall drinks of water like Cooper, James Stewart, and of course the classic man’s man John Wayne. Cooper maintains his regal frame with distinguished angles etched into his posture. Resonating in the actor’s hero roles like High Noon (1952) and The Westerner (1940), his authoritative physicality imposes even in his occasional comic roles, such as Ball of Fire (1941) where his character Professor Bertram Potts finds his hardened center despite his gangly academic clumsiness. Cooper’s signature became the strong-but-silent type, so that when Howard Hawks set out to film Sergeant York (1941), the real Alvin York would only sign over the film rights to his book if Cooper agreed to play him. In the complex role of Link, Cooper’s understated, outwardly low-key touches help bring to light the character’s emotional duality, which later bursts with the film’s implacable violence.

Upon his arrival, Link arranges stable lodgings for his horse, changes his cowboy garb to more respectable attire, buys a train ticket to Fort Worth, and waits for its arrival. A former outlaw now aged and out of place, Link has reformed to pacifism, carrying a gentle and quieted temperament in desperation to remain unnoticed. With secrets to hide, he identifies himself as either “Link Jones from Good Hope” to those he trusts, or “Henry Wright from Sawmill” to those he does not. But this character is more emblematic as the film’s title suggests. “West” is a relative term comprised of two potential meanings within the film: The Old West exemplifies the infinite frontier—a savage and lawless place without boundaries, riddled with outlaws, suitable only for individualists prepared for a tough, solitary lifestyle. Meanwhile, The New West encompasses Manifest Destiny, a virtual and often literal gold mine, someplace fresh, filled with opportunity for industrial expansion, waiting to be quarried—The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of. But The New West is an inevitably conquered land, contained within borders and maps and railroad tracks. Split between these two personas, Link bears a figurative connection between the unruly frontier and the reformed West, his name, meaning connection or bond, signifying the transition between the two.

Link’s Old West criminal history has been masked by his newfound home in Good Hope, his sins confessed to and forgiven by his wife and fellow citizens. Indeed, they trust him with the town’s savings as he travels to Fort Worth to hire their first schoolteacher. But Mann never shows us Link’s spiritual haven, since his film develops into a tale about The Death of the Old West. Instead, Link is disconnected from his asylum on the train, which sends him crashing back into the horrors of his past. The train enters the station sounding its whistle and wafting steam from below. Link, having never seen such a train before, takes a few shocked steps back. “That’s the ugliest thing I ever saw in my life,” he says. Once boarded, Link takes an open seat and Cooper’s long legs supply a humorous, symbolic moment when the train’s squashed compartments prove too small to contain this Man of the Old West, forcing him to sit to the side. Representative of the losing battle of the untamed frontier against the ongoing civilizing process spreading from the East, Link surrenders to the train, existing as both a member of the New West and the Old West uncomfortably cramped into a single slot.

Plagues of self-identity commonly divide Mann’s Western heroes, and though the central conflicts in his narratives are widespread within the genre, each is made more severe by his heroes’ atypical inner battles. Attempting to progress along with the world around him, Link has abandoned his former lawlessness to be civilized, save for his past’s instincts that still haunt him. As much as he tries, Link cannot wholly rid himself of the violent impulses taught to him during his youth. And so, Link’s expedition is an emotional epic, through the frontier penetrated by the railroad, helping to finally settle his own ongoing war between the Wild West and civilization. All at once the train is robbed, and during the chaos Link and two other passengers are left behind. He guides pleasant motormouth Sam Beasley (Arthur O’Connell) and dreamy-eyed lounge singer Billie Ellis (Julie London) across barren country to his nearby adolescent home, only to find it occupied by a pack of wolves—Link’s former gang, which he abandoned long ago. Fearing his death and those of his two friends, Link plays along and insists the Prodigal Son has returned to rejoin. Meanwhile, fear quiets Beasley, and Ellis finds Link has spoken for her, insisting “She’s my woman,” the only woman in a room full of criminals.

The gang sniffs about in disbelief that Link’s return was voluntary. But overripened gang spearhead Dock Tobin, a cracking silver-haired outlaw played by Lee J. Cobb, once mentored Link in the ways of robbery and murder like a father to a son, and so he remains hopeful, deficiently and dreamily so, that Link’s homecoming will mark a new Renaissance in the posse. Cobb lends Tobin an unhinged madness strapped to dying, crazed, and obsolete Old West ideals. The actor barks his dialogue with searing howls, recalling his performances in On the Waterfront (1954) and Thieves’ Highway (1949). Except he quiets down in Man of the West occasionally like a tired drunk, somberly mulling over Tobin’s hopes and disappointments. Illustrated by a beautiful train wreck performance, Tobin suggests Link’s fate had he chosen to remain an outlaw.

Relentlessly challenging Tobin is Link’s gruff gangmember cousin Coaley (Jack Lord), who makes a power play by advancing on Ellis in front of the group, forcing her to strip item by item, all the while with a knife at Link’s throat. Her female displacement and vulnerabilities among Western outlaws becomes (nearly) naked truth. Paced with a torturously slow tempo, the stripping scene is excruciating to behold and yet tastefully filmed—with none of the blatant imagery we would expect from later directors like Sam Peckinpah and Sergio Leone. For Mann, this scene is not about the act of humiliation toward Ellis, rather Link’s shame and powerlessness to protect her, leaving Mann’s hero with only one solution: vengeful retribution. “There’s a point where you either grow up and become a human being, or you rot, like that bunch,” Link explains. But as much as his newfound pacifism has saved him, he struggles to swallow his instincts: “I want to kill every last one of those Tobins. And that makes me just like they are.” Finally, Link acts on those bottled-up sentiments and becomes Mann’s model revenge-bent hero.

Beating Coaley down in one of cinema’s most brutal fights, Link claims his victory by tearing his cousin’s clothes off like an animal, shouting “How does it feel?!” And yet, he hesitates in killing Coaley, unwilling to reduce himself to Tobins’ lows—a weakness that leads to two deaths: Beasley, who dives in front of Coaley’s Link-intended bullet, and Coaley, shot down by Tobin for pulling a gun in a fist fight. Link’s weakness for killing is not repeated. When Tobin leads the gang to rob the quixotic bank at the mining settlement of Lasso, Link scouts ahead only to find a deserted ghost town bereft of life. Knowing the gang will follow, he prepares an ambush and shoots them down in a thrilling gun battle across rooftops and around corners. He returns to their rendezvous to confront Tobin, who remained behind to ravage Ellis. “You’ve outlived your kind and you’ve outlived your time,” Link proclaims, enraged with Ellis’ rape, his voice ringing through the canyon. “And I’m coming to get you!” Though Link insists on turning Tobin over to the law, Tobin, this last archaic devotee to a dying era, refuses to surrender. They finally meet for a one-on-one showdown in nearby stony badlands, where our hero is forced to shoot the villain down in classic Western form. Tobin’s body gracelessly rolls down the hill on which he stands, signaling The Death of the Old West.

When viewing Man of the West for the first time, the viewer feels pulled away from an analysis of the direction by the film’s demand for full surrender to the story. This is, of course, due to Mann’s expert telling of that story. Based on the novel by Will C. Brown, the screenplay by Reginald Rose uses limited space and fully described environments to create dramatic tension. A former playwright of works including the claustrophobic 12 Angry Men, Rose sets Link’s extensive emotional journey in four distinct locales: the train, the shack, the ghost town, and the rocky hills of the final showdown. Mann paints each landscape with a separate palate, and progressively, as they move further and further away from civilization, the potential for Link’s desired way of life slowly fades through visual metaphor. The opening town and the train are green with life and industry; the shack shows signs of life in surrounding farmland, but itself remains skeletal brown dead wood; and as Link plummets into the wasteland of his past, the backdrop becomes increasingly barren and jagged, until the penultimate climax at the dusty, desert ghost town void of life, preceding the rocky cliffs where Tobin dies.

Mann’s approach was distrustful toward the romantic, sweeping views of the West attributed to idealist filmmaker John Ford (My Darling Clementine (1949) and The Searchers (1956)). Ford set his stories against landscapes and often considered his narrative secondary to the overriding environment; something greater, be it God or America or Manifest Destiny, exists in Ford’s landscapes, and at times that intangible element is unclear in Ford’s pictures. Meanwhile, Mann often suggests an alternate Western environment where, without his narrative arc and the insights of his camera, hero and villain would otherwise be too close to call until the final frames. Combining images and ideas into a whole body, Mann unites formal technique and narrative into a single living, breathing individual. His landscapes are not worlds unto themselves; through their use, we better understand the characters occupying their space, like a conceptual-philosophical device. Whereas Ford’s are occasionally overwhelming places where characters disappear into the beauty and sometimes frightening vastness of the West.

Man of the West is Anthony Mann’s shining conceptual project and his last great Western. Today this unsung masterpiece seems like a grand finale and theoretical meridian of his ten-year journey into the Western genre. Here his formal skill and narrative tropes solidify into a sole modus operandi, heralding future rebellious Western filmmakers like Peckinpah and Leone to follow. Mann’s work, though not extensively recognized as that of an auteur in the United States, has been praised overseas by French cineastes François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard as that of a genius-artist. Godard aptly described the director’s opus as “both art and the theory of art.” But because his presence as film-maker refuses to outperform his onscreen narrative, Mann’s output contains an intricacy hidden from the untrained eye by its outright straightforwardness. This illusory simplicity leaves Mann notoriously undervalued as a director and particularly as a director of Westerns. Discovering his pictures is an affecting experience not initially grounded in analysis, but rather our unrefined emotional participation in cinema.

Bibliography:

Basinger, Jeanine. Anthony Mann. New and Expanded Edition. Middletown: Wesleyan, 2007.

Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review