The Definitives

M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

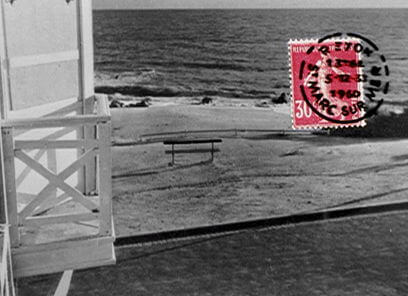

Take a vacation from your humdrum daily life. The Hôtel de la Plage, an exquisite French resort, offers a sleepy beach, tennis courts, meals included, and your usual assemblage of civil, middle-class clientele. Swim in gentle waters. Take a picnic. Chit-chat with fellow vacationers… Revel in the mundane. With his delicate joy M. Hulot’s Holiday, filmmaker Jacques Tati invites you to unwind and observe vacationing aesthetics for their oftentimes boring, trivial, silly limitations. Tati abandons narrative and even dialogue that would associate his film with conventional cinema, directing a series of vignettes designed to make us laugh through ever-subtle physical gags and observations, all in the guise of his famous alter ego: the awkward and apologetic Monsieur Hulot. With M. Hulot’s Holiday, Tati gave the audience of postwar France a filmic vacation, since most could not afford the luxury themselves; at the same time, his criticism showed them what they were not missing. Filmed in black and white, the director’s one note of color appears on the last frame: a postal mark in the upper right-hand corner, stamping the film as a motion picture-postcard offered by Tati to the viewer.

While filming his previous feature, 1949’s Jour de fête, Tati witnessed a packed countryside thanks to French middle-class vacationers finally flooding resorts after WWII. Seeing first-hand the hassle of much-needed leisure, Tati visualized ripe satirical prospects in the pointless, paradoxical holiday process. Paradoxical because, Tati himself noticed few vacationers were actually enjoying themselves; many were quite bored or even additionally stressed by the involving process of taking furlough. Roads filled with traffic, trains overstuffed with passengers, and normally sleepy resorts were crowded with all kinds, most stricken with ennui, and only the occasional individual having fun. Artistically, his inspiration came from Emile Reynaud’s Autour d’une cabine (“Around a Beach House”), a fifteen-minute “Praxinoscope” feature from 1894, shown years before the Lumière brothers arrived on the scene with their cinématographe. A stationary photograph in the short’s background provides the setting for animated figures in the foreground. Reynaud’s short depicts male and female vacationers on a beach with two tents—the same striped tents we see in M. Hutlot’s Holiday. They play with a stray dog, wade in the water, and, of course, flirt. With each animated frame individually painted by Reynaud himself, the result is crude, but clearly inspired Tati’s concept pictorially and, as much as a theme exists within Tati’s film, thematically.

Floundering through his vacationer’s tedium, Tati’s enduring figure Monsieur Hulot enters the picture as a rarity capable of enjoying himself under such duress, perhaps because Hulot’s childlike impression of his surroundings renders him incapable of having a bad time. All the norms take their trains, buses, and fancy automobiles out to the beachside resort. Hulot putts along in his ragged 1924 Amilcar—an antique even in 1953, the year of this film’s release—whose pathetic, duck-squeak horn barely wakes a stray dog sleeping in the middle of the street. Hulot’s jalopy muddles along a country road, other cars passing by, causing this positively uncomfortable driver to swerve nearly into the ditch. When he arrives at the Hôtel de la Plage, his loud vehicle pops and grinds. Children come running to see what has happily disrupted the serene resort, the locale of Hulot’s seemingly first vacation, and his first of many appearances in Tati’s films. As Hulot arrives, the viewer soaks in Tati’s mise-en-scène by participating in the vacation setting. The location—an actual picture-perfect resort on Saint-Marc-sur-mer in the south coastal province of Brittany—and the highly abstract-yet-familiar character types populated throughout were of Tati’s own discovery and design. Indeed, the film’s every detail was labored-over by the director, writer, producer, choreographer, and star: Jacques Tati. His method consists of coordinated gags interchanged with occasional slapstick, which rely on Hulot’s mannerisms, but more importantly on Tati’s ideal location (though some interiors were filmed in-studio). That his picture lacks plot allows Tati’s humor to draw from everyday circumstances and in turn preserves the filmic experience into one about witnessing the confused antics of bumbling vacationer M. Hulot or those he encounters. The film is all the more extraordinary for its simplicity. As a result, viewers, immersed in Tati’s innovative mixture of soft realism and caricature, never really bursts into a hooting laughter, but we recognize the truth, irony, or silliness of Hulot’s situations—always with grand smiles on our faces.

Floundering through his vacationer’s tedium, Tati’s enduring figure Monsieur Hulot enters the picture as a rarity capable of enjoying himself under such duress, perhaps because Hulot’s childlike impression of his surroundings renders him incapable of having a bad time. All the norms take their trains, buses, and fancy automobiles out to the beachside resort. Hulot putts along in his ragged 1924 Amilcar—an antique even in 1953, the year of this film’s release—whose pathetic, duck-squeak horn barely wakes a stray dog sleeping in the middle of the street. Hulot’s jalopy muddles along a country road, other cars passing by, causing this positively uncomfortable driver to swerve nearly into the ditch. When he arrives at the Hôtel de la Plage, his loud vehicle pops and grinds. Children come running to see what has happily disrupted the serene resort, the locale of Hulot’s seemingly first vacation, and his first of many appearances in Tati’s films. As Hulot arrives, the viewer soaks in Tati’s mise-en-scène by participating in the vacation setting. The location—an actual picture-perfect resort on Saint-Marc-sur-mer in the south coastal province of Brittany—and the highly abstract-yet-familiar character types populated throughout were of Tati’s own discovery and design. Indeed, the film’s every detail was labored-over by the director, writer, producer, choreographer, and star: Jacques Tati. His method consists of coordinated gags interchanged with occasional slapstick, which rely on Hulot’s mannerisms, but more importantly on Tati’s ideal location (though some interiors were filmed in-studio). That his picture lacks plot allows Tati’s humor to draw from everyday circumstances and in turn preserves the filmic experience into one about witnessing the confused antics of bumbling vacationer M. Hulot or those he encounters. The film is all the more extraordinary for its simplicity. As a result, viewers, immersed in Tati’s innovative mixture of soft realism and caricature, never really bursts into a hooting laughter, but we recognize the truth, irony, or silliness of Hulot’s situations—always with grand smiles on our faces.

Much of our enjoyment comes from the appreciation that Tati’s garden variety vacation spot is littered with universal, prototypical characters: an old wandering couple, bored children, the (mature) rambunctious Englishwoman, a young intellectual man, a stuffy waiter mouthing complaints to himself, and, of course, a head-turning girl. Tati’s array of familiar “types” is outwardly cliché, but each wholly represents their classification to comic effect, so that the otherwise bland beach and hotel lounge become places of happiness and familiarity. Quaint, genial characters fill the screen, each familiar in their own way. Strolling about in a two-person procession, an aged husband follows behind his wife like a tail, tossing away each addition to her persistent collection of seashells, and rolling his eyes as she counts boats at sea. One child keeps busy by burning holes in a tent with a magnifying glass; the boy’s summer day gets even better when he turns his lens onto a sun-bather. But since we primarily follow Hulot, these supplementary vacationers become familiar as faces other than Tati’s, serving as foundational tropes for Hulot to play against, thus making his arrival and subsequent disruption of their orderliness all the more enjoyable for the viewer.

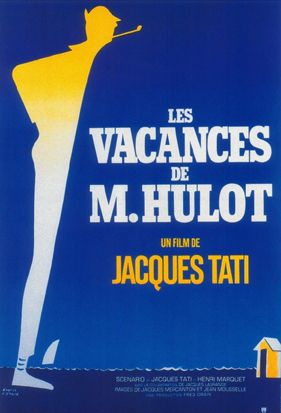

But who exactly is Monsieur Hulot? Where does he come from? How does he earn his living? Such questions are meaningless, since Hulot remains an assemblage of patterns we follow and take pleasure in identifying—as opposed to a fleshed-out personality we must penetrate to discover. With Hulot, there is nothing concealed; he simply is… His angled posture rises straight up from his feet, tilting forward at his waist to point his nose out inquisitively, a look punctuated with his standard pipe and fisherman’s cap with the rear half of its bill turned upward, creating a point at the hat’s front. His hands often rest on his hips as if to create wings, elbows back, somehow keeping his torso weight—Tati was a tall man—from toppling him forward. This makes him step with a sort of graceful-yet-inept gazelle stride, at once beautiful and hilarious. Bouncing on his toes as he walks, the Earth’s gravity fails to impact Hulot as it does the rest of us. He avoids straight paths as he meanders about, stopping to take a look at each and ever thing or person. Give a nod to so-and-so; poke his nose at this or that. His signature cap pulled down to his eyebrows, Hulot’s face is curious; by the look of him, either he is a genius or a complete numbskull. His appearance and behavior remain too alien to identify which.

But who exactly is Monsieur Hulot? Where does he come from? How does he earn his living? Such questions are meaningless, since Hulot remains an assemblage of patterns we follow and take pleasure in identifying—as opposed to a fleshed-out personality we must penetrate to discover. With Hulot, there is nothing concealed; he simply is… His angled posture rises straight up from his feet, tilting forward at his waist to point his nose out inquisitively, a look punctuated with his standard pipe and fisherman’s cap with the rear half of its bill turned upward, creating a point at the hat’s front. His hands often rest on his hips as if to create wings, elbows back, somehow keeping his torso weight—Tati was a tall man—from toppling him forward. This makes him step with a sort of graceful-yet-inept gazelle stride, at once beautiful and hilarious. Bouncing on his toes as he walks, the Earth’s gravity fails to impact Hulot as it does the rest of us. He avoids straight paths as he meanders about, stopping to take a look at each and ever thing or person. Give a nod to so-and-so; poke his nose at this or that. His signature cap pulled down to his eyebrows, Hulot’s face is curious; by the look of him, either he is a genius or a complete numbskull. His appearance and behavior remain too alien to identify which.

Hulot’s methodically designed physical nuances demand comparison to the great silent film master Charles Chaplin, whose jokes are clear and exaggerated, whereas Tati prefers (sometimes literally) muted subtlety constructed from slow builds to understated punchlines. Monsieur Hulot and Chaplin’s Little Tramp are aesthetic opposites, despite often reaching the same comical result: the Tramp leans back; Hulot leans forward. The Tramp’s clothes are comically baggy; Hulot’s slacks seem a size too small, so striped socks peak out from the bottom. The Tramp waddles in short steps; Hulot takes long strides. Pointing out these reversals is not meant to discredit Tati. Never for a moment do we feel Tati envisaged Hulot from Chaplin’s work. On the contrary, these opposites are underlined to demonstrate that Chaplin and Tati designed wholly different subjects, complete with arduous pre-planning down to every last detail, to reach separate artistic objectives, yet ultimately the same goal—to make moviegoers laugh. Beyond physical specifics, Chaplin sought loud and boisterous humor in comparison to Tati’s tranquil yet equally labored-over tone. Both filmmakers spent weeks envisioning elaborate gags and were true artists of their craft.

The easiest way to differentiate their individual methods resides in the audience’s shifting relationship amid the comic figures, notably the directional flow of humor. Whatever the particular gag may be, the Tramp is always responsible, the instigator, the purveyor of the joke; Chaplin sought to make his audience laugh with him, because he was smarter than the world at which he poked fun. Tati prefers that we laugh at Hulot based on whatever situation he haphazardly falls into. He is the brunt of our laughter, always responsible for some slip-up or grand mistake, but without the Tramp’s desperation to entertain himself. Think of humor as a tangible force or energy: for each gag, this energy is discharged by The Tramp, but absorbed by Hulot. Take the scene in M. Hulot’s Holiday where a man stands on the beach next to his boat, painting its name onto the hull. All at once, the locked winch crank releases, and the rig rides on its trailer wheels back into the ocean. The painter’s brush remains stationary, inadvertently carrying a long, ruining brushstroke across the ship’s front. A crowd gathers to inquire what happened. Looking about, the owner finds no one responsible. And then we see Hulot, standing before a post with, unbeknownst to him, his towel wrapped around it. He pulls it back and forth to dry his back, down to his bottom and then feet, but around the post his towel never touches his body. He goes through the motions nonetheless, his eyes nervously shifting between the boat owner and nothingness. Hulot plays an oblivious defense. A stretching jogger trots along through the scene. Hulot follows, imitating the jogger’s motions. Once out of sight, Hulot sprints away to escape, dashing behind a tent, clearly the cause of the whole ruckus.

The easiest way to differentiate their individual methods resides in the audience’s shifting relationship amid the comic figures, notably the directional flow of humor. Whatever the particular gag may be, the Tramp is always responsible, the instigator, the purveyor of the joke; Chaplin sought to make his audience laugh with him, because he was smarter than the world at which he poked fun. Tati prefers that we laugh at Hulot based on whatever situation he haphazardly falls into. He is the brunt of our laughter, always responsible for some slip-up or grand mistake, but without the Tramp’s desperation to entertain himself. Think of humor as a tangible force or energy: for each gag, this energy is discharged by The Tramp, but absorbed by Hulot. Take the scene in M. Hulot’s Holiday where a man stands on the beach next to his boat, painting its name onto the hull. All at once, the locked winch crank releases, and the rig rides on its trailer wheels back into the ocean. The painter’s brush remains stationary, inadvertently carrying a long, ruining brushstroke across the ship’s front. A crowd gathers to inquire what happened. Looking about, the owner finds no one responsible. And then we see Hulot, standing before a post with, unbeknownst to him, his towel wrapped around it. He pulls it back and forth to dry his back, down to his bottom and then feet, but around the post his towel never touches his body. He goes through the motions nonetheless, his eyes nervously shifting between the boat owner and nothingness. Hulot plays an oblivious defense. A stretching jogger trots along through the scene. Hulot follows, imitating the jogger’s motions. Once out of sight, Hulot sprints away to escape, dashing behind a tent, clearly the cause of the whole ruckus.

Never rascally or scampish or endearingly wicked like Chaplin’s Tramp, Hulot’s unconscious blundering is his greatest appeal: “He does not know that he is being funny,” Tati confirmed in an interview. Pattern obliviousness guides him into situations like the above-described debacle, and others, characteristic for him and no one else at the Hôtel de la Plage. Always with an impenetrable, confused expression, Hulot’s incomprehensibility keeps him interesting for the viewer. Everyone else in the picture feels familiar, the same old boring fuddy-duddies on vacation the world over. Someone completely foreign, Hulot is the viewer’s pseudo-protagonist (Tati does not offer an antagonist, save for boredom), personifying via antithesis how stodgy Tati’s other vacationers are, while forever endeavoring to be, as one resort patron describes him, “gentlemanly.”

The film’s polarized musical scores call attention to Hulot’s off-beat placement at the resort, with Alain Romans’ light elevator music piano theme entitled “Quel temps fait-il à Paris” (translation: “What’s the temperature in Paris?”) playing throughout. The pleasant tune represents the staid collective of the vacationers, who have nothing to talk about besides the weather back home, and come running whenever the latest edition of the newspaper arrives, hungry for reports about civilization—where they would all rather be. The end of the broadcast day signals their bedtime. Quiet appropriateness dominates their holiday experience. Accordingly, Romans’ music is proper, inoffensive, and polite. Interrupting, Hulot lays down his diegetic musical theme, a writhe jazz record that cuts through the quiet; his selection lasts only a moment, however, as patrons rush to turn off his disruptive racket. When the jazz music strikes later in the film, again angry guests scuttle to the side-room where they found Hulot tapping his toes before; this time they find a young boy standing next to the record player. The opposing music selections suggest the guests at the Hôtel de la Plage form into two groups: those who find Hulot’s antics amusing, and those who do not. Indeed, Hulot best appeals to the young at heart. His last goodbye before the end credits shows him sitting in the sand with children, tossing dirt back and forth.

The film’s polarized musical scores call attention to Hulot’s off-beat placement at the resort, with Alain Romans’ light elevator music piano theme entitled “Quel temps fait-il à Paris” (translation: “What’s the temperature in Paris?”) playing throughout. The pleasant tune represents the staid collective of the vacationers, who have nothing to talk about besides the weather back home, and come running whenever the latest edition of the newspaper arrives, hungry for reports about civilization—where they would all rather be. The end of the broadcast day signals their bedtime. Quiet appropriateness dominates their holiday experience. Accordingly, Romans’ music is proper, inoffensive, and polite. Interrupting, Hulot lays down his diegetic musical theme, a writhe jazz record that cuts through the quiet; his selection lasts only a moment, however, as patrons rush to turn off his disruptive racket. When the jazz music strikes later in the film, again angry guests scuttle to the side-room where they found Hulot tapping his toes before; this time they find a young boy standing next to the record player. The opposing music selections suggest the guests at the Hôtel de la Plage form into two groups: those who find Hulot’s antics amusing, and those who do not. Indeed, Hulot best appeals to the young at heart. His last goodbye before the end credits shows him sitting in the sand with children, tossing dirt back and forth.

Hulot is one of the few vacationers enjoying themselves, perhaps because the norms are too worried about disrupting the systematized nature of things to relax. Hulot seems to strive for their conformity, bumbling through their etiquette yet involuntarily spoils the good time of those dedicated to vacation protocol. Several characters want to break away, spend their time with this unpredictable element in their otherwise tedious getaway. We see the pretty girl, Martine (Nathalie Pascaud), look frequently in Hulot’s direction, not because he is particularly attractive, rather because he is different that the others. Later, the two attend the resort’s costume party together. Hulot, Martine, and some children are the sole attendees to dress for the occasion; everyone else listens to a political speech on the radio in the lounge. Hulot cranks “Quel temps fait-il à Paris” on the record player, inciting everyone to join in dancing. The next night, Hulot ignites a fireworks fiasco, creating another lively interruption. When the holiday comes to an end, before departure, the man of the old strolling couple (René Lacourt) makes sure he shakes Hulot’s hand, having enjoyed himself vicariously through Hulot the entire stay.

Hulot is Tati’s clueless countermeasure to the stale organization of planning a trip, making the jaunt, seeing the sights, and eating meals by the bell’s ring. When patrons run for their newspaper, Hulot takes his too, although he ignores the contents and folds its pages into a silly cap he wears throughout a tennis match. His simplicity is presented as passive, an almost negative instigator, never premeditated, always unintentional. Perhaps his fortuitousness is his appeal, as we certainly cannot place blame on him for his antics, which derive from his nonaligned presence with the world. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a world where Hulot would be at home; hence, Tati used his Hulot character in other films to criticize any number of social conventions. Indeed, the rest of Tati’s career was dominated by M. Hulot, in the same endearing and by no means redundant way Chaplin retained the Tramp throughout his oeuvre. Because Tati’s films are precise exercises of comedic discipline, several years would pass after M. Hulot’s Holiday before the character appeared on the big screen again. In a thirty-five year period, Tati would only direct six feature-length films, four of them featuring Hulot.

Hulot is Tati’s clueless countermeasure to the stale organization of planning a trip, making the jaunt, seeing the sights, and eating meals by the bell’s ring. When patrons run for their newspaper, Hulot takes his too, although he ignores the contents and folds its pages into a silly cap he wears throughout a tennis match. His simplicity is presented as passive, an almost negative instigator, never premeditated, always unintentional. Perhaps his fortuitousness is his appeal, as we certainly cannot place blame on him for his antics, which derive from his nonaligned presence with the world. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a world where Hulot would be at home; hence, Tati used his Hulot character in other films to criticize any number of social conventions. Indeed, the rest of Tati’s career was dominated by M. Hulot, in the same endearing and by no means redundant way Chaplin retained the Tramp throughout his oeuvre. Because Tati’s films are precise exercises of comedic discipline, several years would pass after M. Hulot’s Holiday before the character appeared on the big screen again. In a thirty-five year period, Tati would only direct six feature-length films, four of them featuring Hulot.

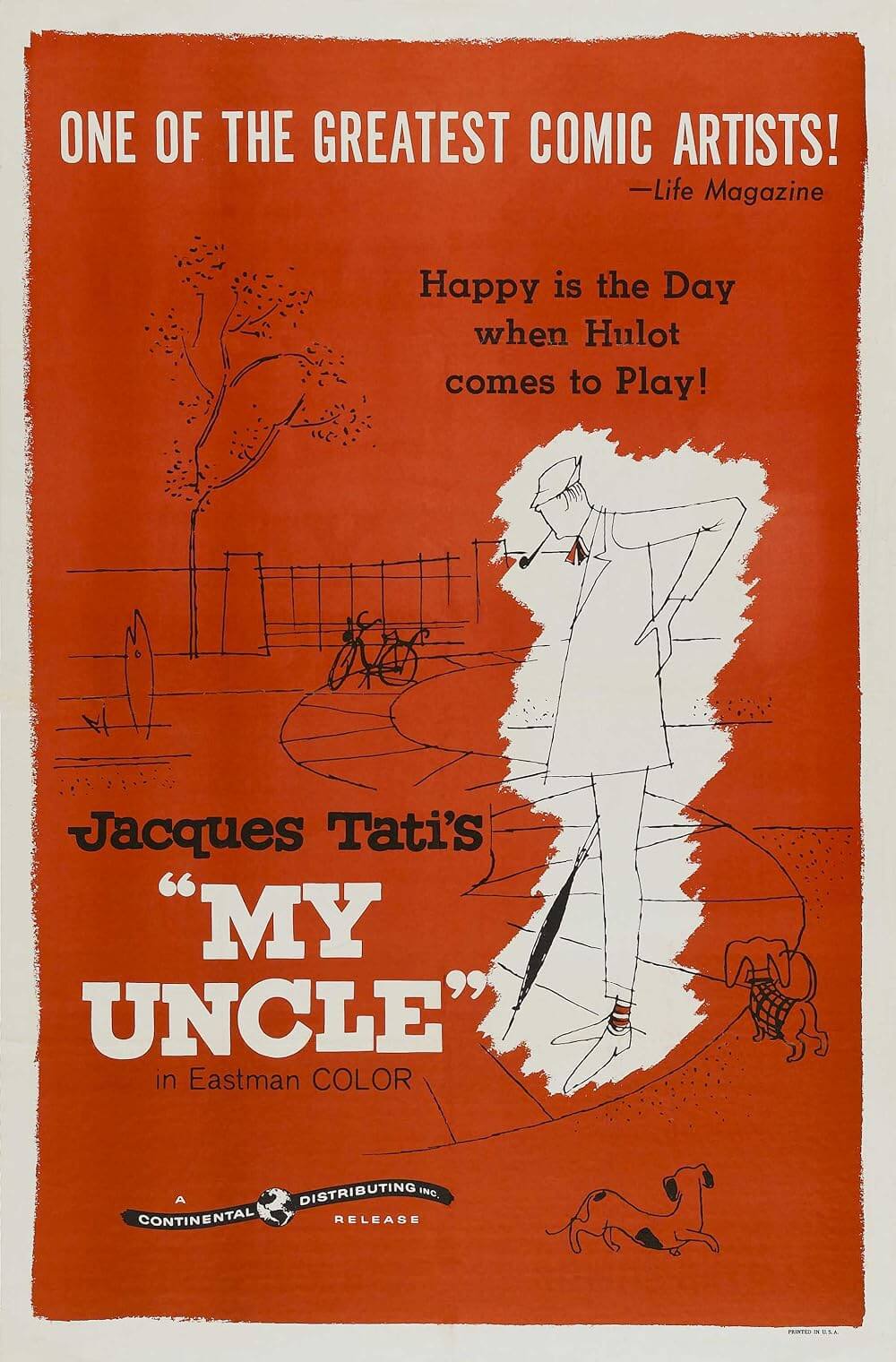

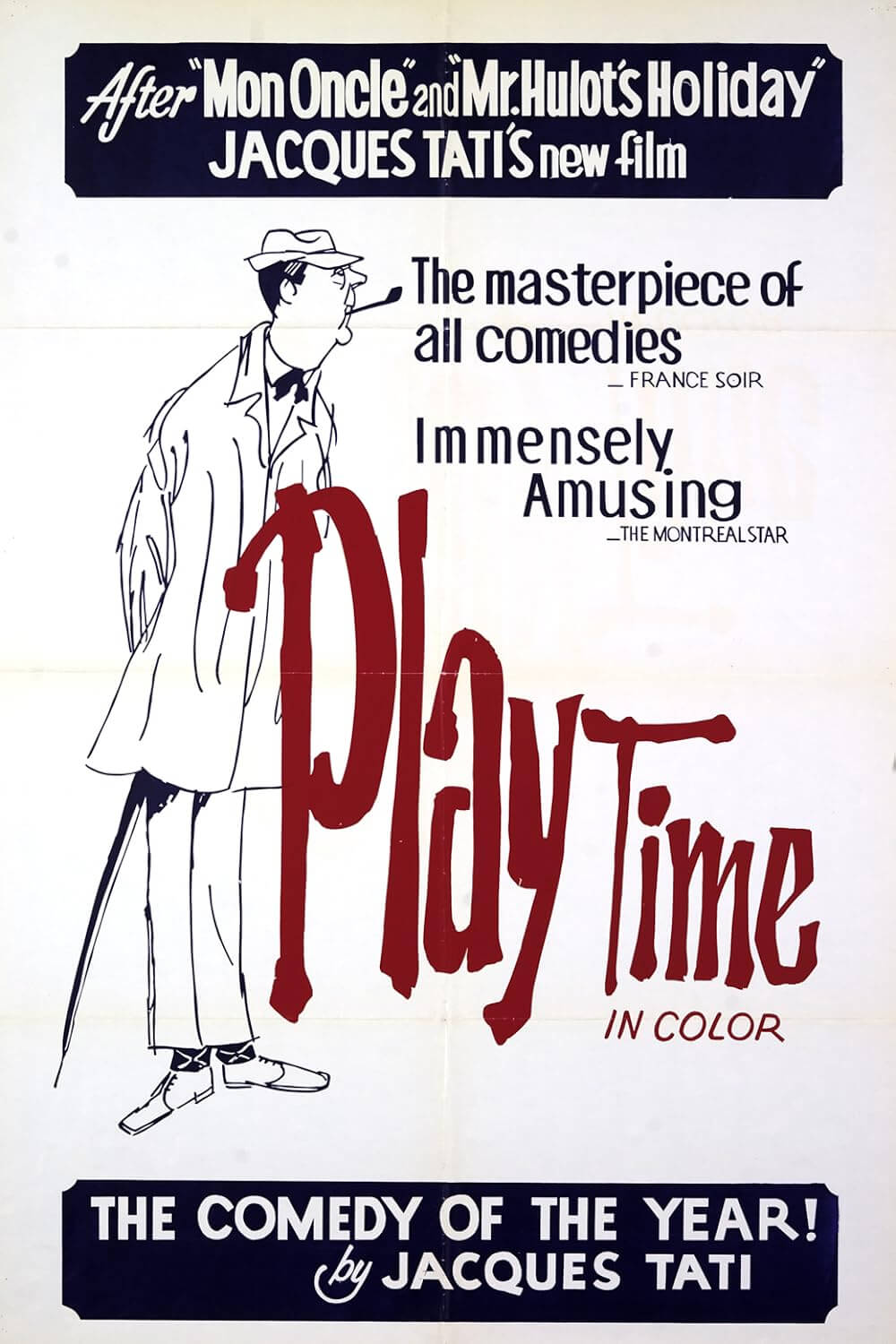

Mon oncle arrived as the second Hulot picture in 1958 and would be the filmmaker’s most critically lauded picture, winning multiple prestigious awards including the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film pits Hulot, signifying the humanist simplicity of prewar Paris, against France’s burgeoning technological modernism. His next was PlayTime, which at the time of its release in 1967 was France’s most expensive picture then produced, requiring millions of Tati’s own income to finish and bankrupting him in the process. Shot in beautiful 70mm, the film plays with almost no narrative and sports anti-industrial themes against a growing metropolis; to illustrate the absurdity of cityscapes, he constructed an unfathomably huge artificial city set he called “Tativille”, in which Hulot is altogether lost. Trafic, Tati’s final Hulot film, arrived in 1972 to address the increasingly outlandish highway construction and auto industry. In each film, Tati surrounds Hulot with progressively modern technological travesties, lamenting the passage of simpler days for a supposedly more “convenient” world, which, of course, Hulot proves is not convenient at all. In essence, Tati’s films are more about environments than characters, making the background just as, if not more important than the foreground.

Take notice of the sound in M. Hulot’s Holiday, or lack thereof. The dialogue’s volume is turned down so that the setting’s audio takes precedence. Half-heard conversations are less essential than repeated sound effects, like the spring on the dining room door or ocean waves brushing tenderly against the beach. Hulot himself remains a silent character, never speaking except to state and spell his name when first checking-in. And what little dialogue remains between other characters is simple and infrequent enough that even non-French-speaking audiences will get the general idea without benefit of subtitles. The audio tracks were recorded after the fact, with dialogue dubbed-in during post-production, giving Tati complete control over each perceptible auditory nuance. Having studied pantomime in his younger days and filming without sound, Tati taught his cast how to mime, instructing them to overemphasize every action. Just as background noise takes precedence over dialogue, bodies outweigh facial expressions. Hulot maintains an almost empty visage, a combination of inquisitive and bemused, because his physical characteristics stand pronounced, defining him more precisely than any words or facial expression could. Tati wants us to view his figures as whole forms. His shots are distant, never close-ups, as if the viewer exists within Tati’s filmed environment.

Take notice of the sound in M. Hulot’s Holiday, or lack thereof. The dialogue’s volume is turned down so that the setting’s audio takes precedence. Half-heard conversations are less essential than repeated sound effects, like the spring on the dining room door or ocean waves brushing tenderly against the beach. Hulot himself remains a silent character, never speaking except to state and spell his name when first checking-in. And what little dialogue remains between other characters is simple and infrequent enough that even non-French-speaking audiences will get the general idea without benefit of subtitles. The audio tracks were recorded after the fact, with dialogue dubbed-in during post-production, giving Tati complete control over each perceptible auditory nuance. Having studied pantomime in his younger days and filming without sound, Tati taught his cast how to mime, instructing them to overemphasize every action. Just as background noise takes precedence over dialogue, bodies outweigh facial expressions. Hulot maintains an almost empty visage, a combination of inquisitive and bemused, because his physical characteristics stand pronounced, defining him more precisely than any words or facial expression could. Tati wants us to view his figures as whole forms. His shots are distant, never close-ups, as if the viewer exists within Tati’s filmed environment.

Indeed, throughout M. Hulot’s Holiday, we too are on vacation, catching the film’s events from a passer-by point-of-view. We observe expressive body types taking shape to classify characters through posture or motion, defining them with an emphatic mold known as “Tatiesque”. M. Hulot’s Holiday, one of cinema’s great treasures, does not reveal itself easily; Tati’s picture requires multiple viewings to gather each detail. Every viewing becomes a new outing, with our experience growing beyond the initial spotlight on Hulot’s at once graceful and clumsy profile. Upon revisiting, we realize he is merely a facet in a larger jewel cut with incredible precision by Jacques Tati. Successive viewings are dedicated to the music, particular background characters, or Tati’s ingenious use of sound—any range of details living within the film’s milieu. We lose ourselves in the Hôtel de la Plage’s hilarious and seemingly effortless atmosphere, orchestrated with incomparable care and joyous delight by a rare specimen, a master craftsman and artist of comedy.

Bibliography:

Bellos, David. Jacques Tati: His Life and Art. London: Harvill, 1999.

Chion, Michel. The Films of Jacques Tati. Toronto: Guernica, 1997.

Dondey, Marc. Jacques Tati. Paris: Ramsay, 1987.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review