The Definitives

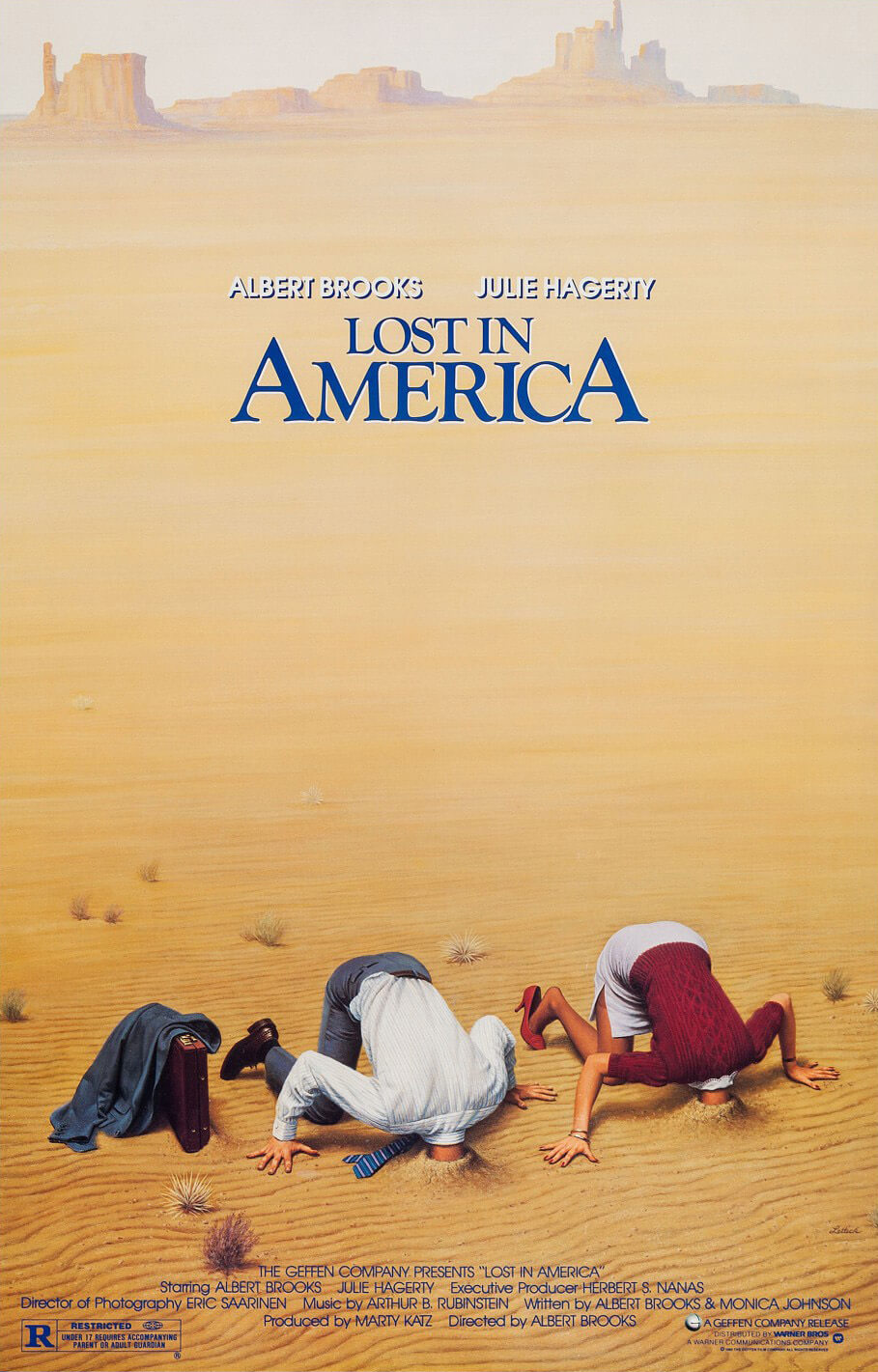

Lost in America (1985)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Made at the height of Reaganism, Lost in America follows the well-heeled Los Angeles couple, David and Linda Howard, played by Albert Brooks and Julie Haggerty. The first scene finds David lying awake in bed, fretting about whether he and Linda have made the right decision to buy a new, larger house. Their things have already been boxed up, anticipating that in the morning, David will earn his long-awaited promotion to an advertising executive. He even started talking to the Mercedes dealership about a new car. But David wonders if the house will be enough. Should they have moved further away from their current home or found a house with a tennis court? Then Linda, her patience at an end, drops a bomb: “Sometimes I wish we were more irresponsible.” It’s a remark that festers, regardless of her assurance that, “Everything is going to be better” in their new life. When David does not get his promotion as expected, he has a meltdown, lashes out, and loses his job. His life has not gone as planned, and it’s the catalyst for David to take Linda’s remark to heart. As both feel trapped by their unfulfilling careers and dispassionate lives inside their suburban bubble, they resolve to liquidate their material possessions, buy a Winnebago, and drop out of society. They will live on the road and find themselves, modeling their lives after Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider (1969). But if you recall, it didn’t work out too well for Fonda and Hopper, and it doesn’t work out well for Brooks and Haggerty either.

Brooks’ film, co-written with his regular collaborator Monica Johnson, observes that Americans have condemned themselves to a prison of materialistic comfort and existential discontentment. Long before the Digital Age sealed Americans into extreme cultural bubbles, Brooks identified how the safety of a steady income, a comfortable home, and a sense of financial security represented another kind of asylum—one in which most Americans were eager to be committed. The alternative uncertainty, without the “Nest Egg” of $190,000 the Howards have after they cash out their savings and liquidate their various assets, is too frightening to bear. From the very start, their entire approach to finding themselves requires the lynchpin of capitalist society: money. “This is what we talked about when we were 19,” David beams. “Remember we kept saying let’s find ourselves? Well, we didn’t have a dollar, so we watched television instead.” Made in 1985, Lost in America remains one of the funniest films ever made, and it still rings true for a culture that wrestles with our inability to disconnect from the internet—the tool that should have brought us together, but instead, perpetuates isolation and loneliness. Indeed, the Howards’ plan is like trying to disconnect except for the occasional status update.

After cashing in their materialistic lifestyle for the equally unsound promise of freedom on the open road, the Howards visit Las Vegas, where they plan to begin their new adventure after getting remarried. David has fully committed to the Easy Rider lifestyle, complete with “Born to Be Wild” on the radio and yellow-tinted glasses like those worn by Fonda. But they should have known that if your first stop in your escape from a materialistic society is Las Vegas, you’re doomed. Linda convinces David to say goodbye to their former lives with one last hurrah in a Las Vegas hotel, though their “junior bridal suite” affords neither the large bathtub nor the single bed they hoped for. When David wakes in the morning, Linda is gone. He finds her at the roulette table, her hair frazzled and eyes crazed, chanting the words “Twenty-two! C’mon, twenty-two!” on repeat. Linda has so long repressed her dissatisfaction that she has released her tensions in a colossal meltdown that has depleted the “Nest Egg,” leaving them with just $800. Though the incident thrusts David and Linda into true freedom from society, they yearn for a sense of security. Lost in America is not a comedy that finds its protagonists settling into their alternative lifestyle for a happy ending; rather, David ultimately resolves to “eat shit” and beg for his job back. It’s an unconventional ending to a film that adopts the familiar tropes of a road movie and a comedy of remarriage. But then, Brooks has always taken commonplace ideas and reworked them from a place of conceptual humor and insight.

Brooks specializes in comedies about the Baby Boomer generation, its contemporary anxieties, unabashed materialism, and disproportionate sense of entitlement. And yet, he usually plays someone whose life looks rather pleasant: a talented or successful person living in nice house, in a relationship with an intelligent and attractive partner, and driving an expensive car. Brooks rarely plays someone with a dull job; his characters are almost exclusively creative types. He has played a documentarian, a Hollywood film editor, an advertising executive (twice, in Lost in America and Defending Your Life), a science fiction author, a Hollywood screenwriter, and a stand-up comedian. The irony is, despite professional success and having a creative outlet, his characters usually feel dissatisfied. Brooks’ self-absorbed characters over-analyze every situation and always believe they’re right, yet they have no sense of emotional honesty with themselves. It’s a type undoubtedly echoed by various Woody Allen characters or Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm, although Brooks has far more charm. He cuts into the characteristics of his generation without sermonizing about the defects of his fellow Boomers. Instead, he slices into a condition unique to Americans and turns it into the stuff of comedy. When David haggles with his Mercedes dealer in Lost in America, he can only feel disappointed that the car comes equipped with a thick vinyl “Mercedes leather,” instead of the real thing. Without genuine leather, it’s something less than, but David can’t afford the real thing. What’s the point of having it if you can’t have the best?

In his relatively modest career of seven films in just under thirty years, the prototypical Brooks protagonist has resolved to fix the underlying source of his anxieties with extreme measures that rarely work out in his favor. In Lost in America, he recognizes that he’s too concerned with responsibility, so he concocts an elaborate plan to drop out of society and head onto the open road in a Winnebago, upending his life completely. In his hilarious mockumentary Real Life (1979), Brooks plays a version of himself, a documentarian so concerned with realism that he resolves to include the filmmakers in his portrait of the American family. Modern Romance (1981), one of Stanley Kubrick’s favorite films, finds Brooks ending a perfect, loving relationship because he cannot be sure there’s not someone else out there he’s meant to be with. His character in Mother (1996) decides to move back home, using his mother to find the root of his relationship problems with women. When his character in The Muse (1999) can’t sell a script, he hires a Greek muse and caters to her every (expensive) whim in hopes for inspiration, even though he doubts the entire process. Playing another version of himself in Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World (2005), Brooks takes an assignment from the U.S. government to settle tensions in India and Pakistan by finding out what makes Muslims laugh. Only Defending Your Life (1991) varies from this formula of extreme measures and their disastrous outcomes; in the afterlife, after eons of submitting to his fears, Brooks breaks from the transmigratory path to finally go after what he wants: a marvelous Meryl Streep.

The Brooksian persona, the seemingly rational yet neurotic type, always his own worst enemy, stems from his early work as a stand-up comedian and performer on the late-night talk show circuit. In the early 1970s, Brooks appeared as a regular fixture on variety television; he also released two unconventional comedy albums, Comedy Minus One (1973) and A Star Is Bought (1976). He was one of the first of his kind to write comedy about the profession of comedy, dissecting the structure of jokes and comedic stagecraft as his material, which explains why he’s a favorite among his peers. During his early career, he often played entertainers whose confidence before an audience was only matched by their obliviousness and ineptness. This is true of Brooks’ ventriloquist routine, first on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1971, then again on The Flip Wilson Show in 1972, in which he doesn’t attempt to hide his mouth moving in his dummy’s voice. Or consider his mime, a character who hilariously talked to the audience, telegraphing his every movement in a French accent. In a particularly audacious appearance on The Tonight Show in 1974—Brooks was Johnny Carson’s guest dozens of times—he confessed, “Here I am, five years into my career, and my game plan is all off. I have no material left.” He seemed to be having a breakdown on live television. Then he started listing off and facetiously acting out everything a lesser comedian would do if they just wanted an easy laugh—he dropped his pants, hit himself with a pie, and sprayed seltzer in his face. The only other comedians to so daringly turn comedy on its head were Andy Kaufman and Steve Martin. A few years later, in his “Fall Preview” sketch for Saturday Night Live in 1975, one of many short films he made for producer Lorne Michaels, an announcer articulates Brooks’ desire to break “out of his late-night harness.” It was around this time he disappeared for three years to make his motion picture debut. The supremely confident Real Life was another ahead-of-its-time film that predicts digital cameras, motion-capture technology, and the emptiness and artificiality of reality television.

Lost in America is Brooks’ third film, and besides instilling his traits as a comedian and filmmaker—some have reduced him to a “West Coast Woody Allen”—it reveals him to be a careful commentator who resists moralizing to his audience. Unlike Allen, however, Brooks avoids relishing in self-punishment and artistic affectation; he’s not a filmmaker interested in making a formal pastiche of his influences (in Allen’s earlier work, Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini). Rather, Brooks’ style is entirely distinct and straightforward, if not almost classical, even though the subject matter of his films often subverts expectations. His films are well-lit and composed of mostly medium shots, and they function on an even-keel and rarely approach outlandishness. Though many of his takes are quite long, they avoid pretensions and do not call attention to themselves. His shots have an observational quality about them, as if Brooks has conceived a scenario and has structured his formal approach to analyze how that scenario will unfold. The point, in other words, is the structure of the material and its premise, which the form showcases. Moreover, Brooks has a sly way of instilling a political perspective into his comedies. He’s a keen social observer. Besides his undeniable humanizing project of Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World, Brooks also wrote the novel 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America, pubished in 2011, a mordant story of a country driven to collapse by a debilitating earthquake and radical youth groups tired of paying for the debt of older generations. Likewise, Lost in America finds the promise of the American ideal corrupted by the reality of living in a doggedly capitalistic society.

At its core, the film underscores where America went wrong, from the hope of the frontier to the illusion of freedom in Easy Rider’s rebellious bikers, leaving a fractured identity. America’s growth through westward expansion had been ingrained into the country’s value system since the nineteenth century. Journalist John L. O’Sullivan wrote that the success of America depended on overtaking the continent as a matter of its Manifest Destiny, a term that would become increasingly romanticized by American presidents. Similarly, historian Frederick Jackson Turner argued that Americans gained strength as its pioneers explored the western frontier, pushing ever further toward the Pacific Ocean. It was a movement encapsulated by the idea of individualism, the freedom of riding headlong into the unknown, which challenged and hardened the individual through their survival in a lawless, untamed land. The American myth promised individual freedom for those brave enough to seek it, but inevitably, the Pacific marked an end to the land that travelers could conquer. The courageous individuals who found freedom away from the restrictions of civilization were soon followed by settlers who established the signposts of civilization in the West, thus reformatting the wild and removing any hope of discovering one’s individual freedom. Within a few short decades, the America idealized by O’Sullivan and Turner had been subsumed by capitalist civilization. For a brief moment, however, the dream of the open road contained some measure of individual freedom, but it was a pointless, if not self-destructive search inward.

Easy Rider supplied an allegory for the hopeless journey inland. Dennis Hopper’s essential counterculture film from 1969 showcased a series of alternative lifestyles in its trip from Los Angeles to New Orleans, in the opposite direction of Westward expansion. After Peter Fonda’s Wyatt tosses his wristwatch into the dirt and abandons the social construct of time, he and Hopper’s Billy head out on the modern-day horse, the motorcycle, for a meandering adventure into America’s heartland. Flapping their arms like birds on the nation’s empty highways, their desperate search to find some semblance of freedom outside of civilization, the law, sexual taboos, and even the mind, offers them possibilities: an isolated farmer who lives off the land, a hippie commune with a dash of polygamy, and psychadelics. “Do your own thing in your own time,” Wyatt observes as the ultimate goal of their drive. But as their compatriot, Jack Nicholson’s George observes, “It’s real hard to be free when you’re bought and sold in the marketplace.” To be sure, the bikers’ overreliance on their nest egg, earned from selling cocaine in the opening scene, is their undoing. Billy exclaims near the end, “We did it. We’re rich!” But Fonda’s character, nicknamed “Captain America” and appearing decked out in a star-spangled helmet and American flag on the back of his leather coat, knows otherwise. “We blew it,” he says, realizing the money was a chain on their ankle during their entire search for freedom. Lost in America follows a similar trajectory, except it turns the Howards’ failure into a realistic comedy.

By the time Brooks’ film hit theaters in 1985, the counterculture featured in Easy Rider had sold out. Baby Boomers helped bring about America’s descent into the rampant capitalism and excesses fuelled by Reaganism. When the generation could no longer forge its identity and personal freedom by exploring untapped frontiers, and the search inward proved hollow, material objects filled the hole. The expansion West folded back on itself; there was nothing left to explore. America became a society obsessed with consumerism in the 1980s, and from that, its values shifted. No longer was it about acquiring freedom; it was about more work and better financials—a bigger house, a better salary than your neighbor, and a more prosperous life for the kids. Freedom in the 1980s meant the freedom to buy what you want; all you had to do was make sure you could afford it. The signs of capitalism represented fulfillment, whereas the individual was restrained by conservative values associated with Reaganism. Governmental deregulation sought to embolden business, resulting in a consumer culture that spent more than it earned. Maxed-out credit cards became the norm, and in searching for personal freedom through commerce, there was only an unpaid financial and spiritual debt. In terms of Easy Rider, the cultural shift of the 1980s was personified by Dennis Hopper, once a rebellious artist who had gone from making movies with Francis Ford Coppola and Wim Wenders to appearing in My Science Project the same year as Lost in America. Later, he would be Hollywood’s go-to villain of the 1990s, starring as the crazed, cartoonish antagonists of Super Mario Bros. (1993), Speed (1994), and Waterworld (1995). The American ideal had shifted its concern with individual freedom to individual wealth and status.

Rather than censuring his generation or dwelling on America’s consumerism, Brooks relies on the tools of irony and humor in Lost in America. He has the rare ability to find comedy in the most miserable of situations. Most of his films are about disasters, cringe-worthy situations his protagonists often compel and aggravate. But the misfortunes of his characters are the foundation of his humor, going back to his incompetent ventriloquist. “I would say if there’s a heaven, there’s probably no comedy up there,” Brooks told The New York Times. “Comedy and bliss? You don’t see a lot of funny Buddhists.” The ironic disaster of Lost in America is that the Howards lose the very thing they were trying to free themselves from, and then later, they realize they wanted it all along. Listen to the way David talks to Linda (“in the first of many lectures”) about the “Nest Egg Principle,” describing the money she lost as “a protector, like a god.” Over the course of the film, after their stop in Las Vegas, both David and Linda come to worship at the altar of capitalism and regret that their faith ever strayed. The Howards’ experience in the film is one of self-discovery, as they come to grips with the reality that, even as they wrestle with having individual freedom, they would much rather have materialistic comfort.

Their lesson is hard-learned, and Brooks’ comic situations bring David and Linda to the brink, and ultimately self-understanding, through a series of humiliations. When he discovers that Linda has gambled away their Nest Egg, David asks to speak with the hotel and casino manager, played with deadpan aplomb by Gary Marshall. David goes into advertising mode, pitching a campaign in which the Desert Inn gives back the Howard’s Nest Egg. David’s impromptu jingle, “The Desert Inn has heart,” fails to impress Marshall’s character; the Howards receive nothing more than complimentary rooms. After nearly separating at the Hoover Dam, the Howards drive aimlessly through the Southwest before resolving to settle in a trailer park. One place is as good as another, so why not Safford, Arizona? There, David and Linda admit to themselves the practical necessity of employment—he says plainly, “We need money.” Linda lands an assistant manager position at Der Wienerschnitzel, working for a manager with a bad teenage mustache, who had to sleep on it before making a choice. In David’s meeting with an unemployment officer, he explains his work history at one of the world’s largest advertising agencies, with a salary and bonuses that averaged around $100,000 a year. David goes on to explain that he and Linda wanted to find themselves by drastically changing their lives. The officer’s crushing reply: “You couldn’t change your life on $100,000?”

For all of the film’s jabs at the chronic dissatisfaction and materialism of America in the 1980s, it also bears a classical structure as a romantic comedy of remarriage. Comedies of remarriage became fixtures in the screwball scenarios of Hollywood’s Golden Age, including films such as His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940), and The Lady Eve (1941). The narrative structure of these films follows a couple, usually married, as they divorce or separate because of some tense situation. At this point, the woman finds a duller replacement for her husband or lover. But the original husband then endeavors to win back his wife, often through a ridiculous crusade that demonstrates the inadequacies of his temporary replacement. Inevitably, through the original lover’s efforts, the wife’s flame for him reignites, and the couple is remarried, either literally or figuratively. Lost in America follows that classical remarriage structure, in that, for part of the second act, Linda considers leaving David over his anger and ongoing punishment of her for losing the Nest Egg. They never got remarried in Las Vegas, and Linda calls that “the one good thing that came out of this.” She leaves David and hitchhikes with a crazed ex-con (Donald Gibb). David catches up with them at a diner and tries to convince Linda to come back in the Winnebago. Only after the ex-con punches David in the nose does Linda rejoin him. Their commitment to each other returns to normal after their first night in Safford, when the couple remarries through the sacred ceremony of make-up sex.

The remarriage, however, is not exclusive to David and Linda; the structure also applies to the Howards and their relationship with materialist society. Lost in America opens with David and Linda in an uneasy relationship with society. Linda works in a windowless retail office and later admits, “Sometimes I felt like I was going crazy.” David desperately wanted a promotion from creative director to executive vice president; he’s given a lateral move to a new account, which will force them to move from Los Angeles to New York. They both want something more out of life, either more material goods or something altogether different. Their marriage with society ends when the Howards resolve to liquidate and find themselves. But after Linda’s loses their Nest Egg, their flame for society is reignited. The alternative—Linda working at Der Wienerschnitzel and David facing humiliation as a school crossing guard—is too much to bear. The harsh realities of living out Easy Rider do not appeal to these characters, who have lived privileged lives in bourgeois comfort. David admits, “Given our age and these jobs, we won’t see another Nest Egg for… Ever.” And David needs the certainty of the Nest Egg. Their remarriage with society finally occurs when the Howards share their respective plans to resolve the situation: Linda says, “I was thinking that we go to New York as fast as we can.” David adds, “And I eat shit? My plan too!”

As the Howards drive on the nation’s highways to find themselves, the journey of Lost in America is less concerned with feeling adrift in the geographical space of America than the existential dissatisfaction of living in a capitalist society. Aside from a few sights like Hoover Dam and Las Vegas, the Howards see more of themselves than their country. They just pass through poverty on their way from one coast to the other, from one well-paying job to the next, learning an essential lesson along the way: functioning within society requires the sacrifice of individual freedoms. Brooks discovers that the cruelest of all ironies about capitalism is that the more money you have, the more freedom you can buy, but you also buy your way into an existential prison. Lost in America is unquestionably Brooks’ funniest, most cynical, yet most insightful film, and the height of his wincing scenarios about disenchanted creatives. Of course, even as Brooks reminds us that Americans were once pioneers who have, both tragically and hilariously, turned into consumers, he acknowledges the comforts supplied by such a lifestyle. Perhaps all the Howards needed was a little perspective to appreciate their privileged lives. Having a lucrative but unsatisfying job may seem to confine at times, but relatively speaking, it’s worth eating shit to avoid the alternative.

Bibliography:

Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Harvard University Press, 1984.

Green, Daniel. “‘We’re Getting a False Reality Here’: Albert Brooks and the Comic Idea.” Film Criticism, vol. 17, no. 1, 1992, pp. 26–37.

Brooks, Albert, and Gavin Smith. “All the Choices: Albert Brooks Interviewed by Gavin Smith.” Film Comment, vol. 35, no. 4, 1999, pp. 14–21.

Etzioni, Amitai. “A Crisis of Consumerism.” Aftershocks: Economic Crisis and Institutional Choice, edited by Anton Hemerijck et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2009, pp. 155–162.

Tobias, Scott. “Lost in America: The $100,000 Box.” 25 July 2017. Criterion. criterion.com/current/posts/4760-lost-in-america-the-100-000-box. Accessed 11 November 2019.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review