The Definitives

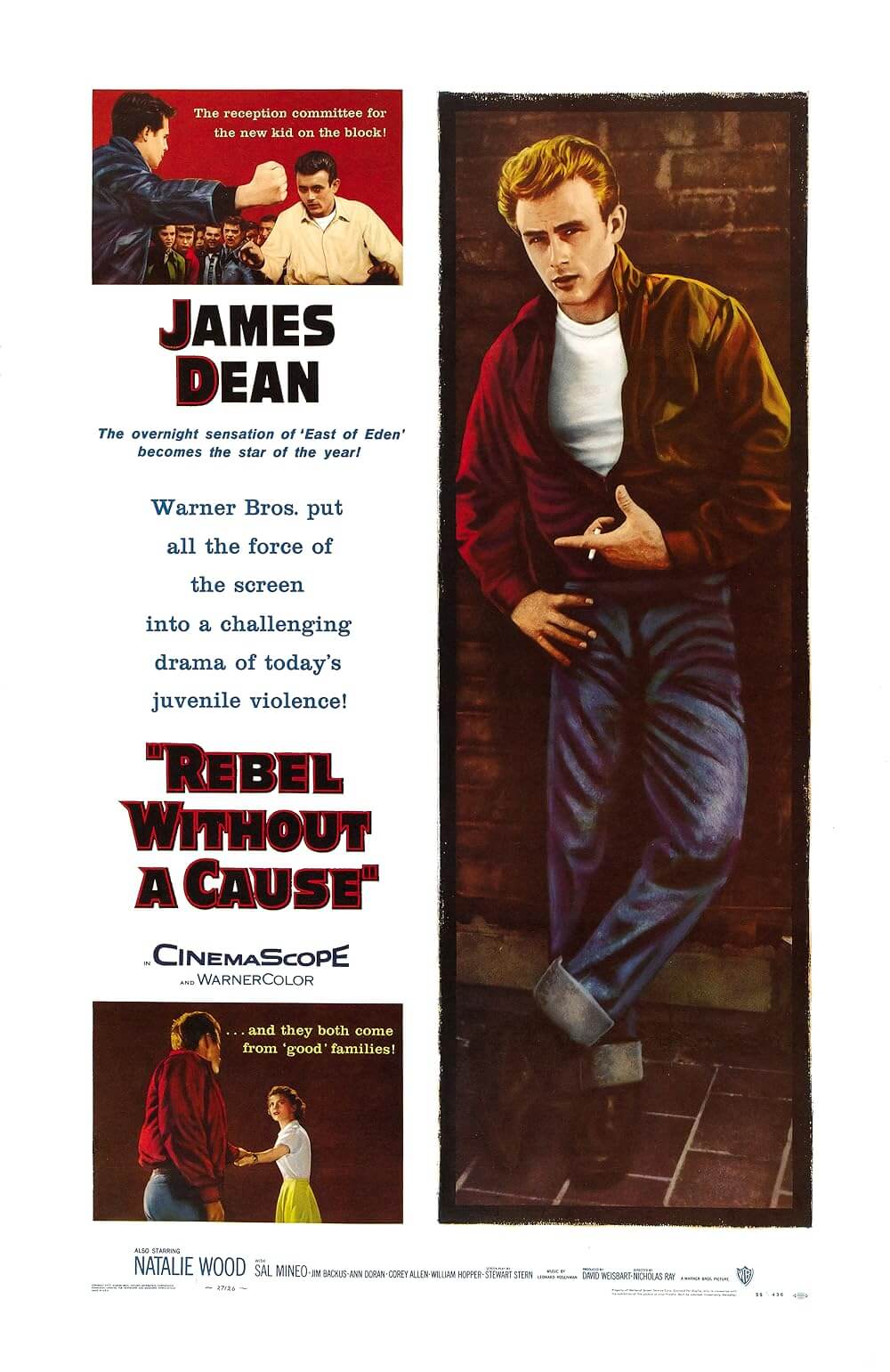

Laura (1944)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Laura opens on a portrait of Gene Tierney, an actress Darryl F. Zanuck called, “The most beautiful woman in film history.” Tierney’s tragically short career was often judged by her appearance and privileged early life. Introduced as a debutante by her well-heeled Connecticut family, Tierney earned headlines for her romances with mogul Howard Hughes, future president John F. Kennedy, and Prince Aly Khan. She was seen as glamorous and serene to a fault, leading to occasional negative reviews of her mannered performances. Her character in the 1944 film, too, is lauded like a goddess by almost every character. “Her youth and beauty, her poise and charm of manner captivated them all,” extols one of Laura Hunt’s admirers. “She had warmth, vitality. She had authentic magnetism. Wherever we went, she stood out. Men admired her. Women envied her.” Such infatuation grows into an obsession with the idea of Laura more than the person behind her appearance, leading to her violent murder before the film opens. And while Tierney did not suffer that grim fate in life, her role and off-screen life share a similar downswing. Both Laura and the actor performing her were shaped according to a fantasy image, causing immeasurable damage in both the film and Tierney’s life.

Often cited as an essential film noir, Laura begins with an atmosphere of murder and nostalgia. Newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) recalls, “I shall never forget the weekend Laura died.” He receives a visit from Det. Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), a simple, gum-chewing detective who occupies his mind with a child’s baseball diamond pocket game. Lydecker tells McPherson about Laura in voiceover and flashbacks, proclaiming he was “the only one who really knew her.” He explains how Laura received her start as an ambitious and successful career woman in New York advertising, and how she was Galatea to his Pygmalion; he helped raise her up from humble beginnings into the life of a sophisticate. And Lydecker expresses a sense of pride and ownership over his creation. But Laura was killed, shot in the face in her apartment with two rounds of buckshot by an unknown assailant. McPherson heads out to interview Laura’s friends, and quite implausibly, Lydecker joins him to observe. There is Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price), her weaselly fiancé who lies about everything and, when caught, quickly admits his deception. There is Bessie (Dorothy Adams), Laura’s worshipful housekeeper. And there is Laura’s wealthy aunt, Ann Treadwell (Judith Anderson), who loves Carpenter and wants him for herself. Everyone’s a suspect.

During his investigation, McPherson spends his nights in Laura’s apartment, reading her diary, thumbing through her letters, sniffing her perfume, drinking her booze, and falling in love with her portrait, which she has vainly hung over the fireplace—a flourish suggested by Lydecker no doubt. After peeking in her underwear drawer, McPherson looks at himself in the mirror with shame, but not so much that he removes himself from the case. He is compromised and he knows it, but he continues anyway. The twist comes when Laura, who has not been murdered, arrives home and finds McPherson passed out in her apartment. The real victim, a model named Diane Redfern from Laura’s agency, had been in her apartment with Carpenter. Once McPherson sees that Laura is alive, she becomes the obvious suspect. Nevertheless, the other suspects remain so devoted to Laura that they’re willing to cover up evidence to protect her from suspicion, even if she’s actually innocent. Carpenter assumes Laura is guilty and takes steps to make her appear less so. McPherson wants to find the killer, of course, but he also hopes to clear Laura’s name for selfish reasons. He has fallen in love with the idea of Laura, which deepens once he sees her in the flesh.

During his investigation, McPherson spends his nights in Laura’s apartment, reading her diary, thumbing through her letters, sniffing her perfume, drinking her booze, and falling in love with her portrait, which she has vainly hung over the fireplace—a flourish suggested by Lydecker no doubt. After peeking in her underwear drawer, McPherson looks at himself in the mirror with shame, but not so much that he removes himself from the case. He is compromised and he knows it, but he continues anyway. The twist comes when Laura, who has not been murdered, arrives home and finds McPherson passed out in her apartment. The real victim, a model named Diane Redfern from Laura’s agency, had been in her apartment with Carpenter. Once McPherson sees that Laura is alive, she becomes the obvious suspect. Nevertheless, the other suspects remain so devoted to Laura that they’re willing to cover up evidence to protect her from suspicion, even if she’s actually innocent. Carpenter assumes Laura is guilty and takes steps to make her appear less so. McPherson wants to find the killer, of course, but he also hopes to clear Laura’s name for selfish reasons. He has fallen in love with the idea of Laura, which deepens once he sees her in the flesh.

Laura’s screenplay doesn’t retain much from the source material. Author Vera Caspary’s story, first serialized in Collier’s Weekly as Ring Twice for Laura, was published in book form in 1942. After Twentieth Century-Fox acquired the screen rights, director-producer Otto Preminger championed the adaptation, despite being on the outs with Fox’s production chief, Zanuck. The two had clashed during the studio’s big-budget adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped from 1938, and Zanuck had removed Preminger from the picture, stalling the director’s career in the process. But while Zanuck was away serving as a war photographer in Europe, executive assistant William Goetz quietly maneuvered Preminger back into the studio to develop Laura. A loose adaptation of the book, the screenplay was credited to Jay Dratler, Samuel Hoffenstein, and Betty Reinhardt. The writers used Caspary’s gimmick of finding a dead woman who gets mistaken as Laura, only to have Laura return as a prime suspect, but not much else. Most of the characters and other details were reworked for the screen. Bryan Foy, head of Fox’s “B” movie unit of programmers, led the production initially. But few besides Preminger, Foy included, believed in the project. Caspary, too, felt her source material would be underserved by a “B” grade film, while Foy and others complained about the script’s quality. But Zanuck read the script and, according to Preminger, liked that it didn’t have a single scene inside a police station. Since Foy wasn’t interested, Zanuck took the project and gave it an “A” budget—an unlikely outcome given Zanuck and Preminger’s rocky past.

Still, Zanuck refused at first to allow Preminger to direct the picture. He sent the script to his studio’s other top-tier directors, many of whom passed, until Rouben Mamoulian, who had not worked for years and needed the money, agreed to take on the project with Preminger serving as a producer. But Mamoulian and Preminger disagreed about how Laura should be cast, shot, and scored, and others seemed unimpressed with the material. Jennifer Jones and Hedy Lamarr both turned down the leading role, leaving Laura to Gene Tierney, then 24, who had cut her teeth on a few underwhelming roles for Fox. However, after the first few days of shooting, Zanuck, Mamoulian, and Preminger were unsatisfied with the early footage. Preminger went to Zanuck and received permission to fire Mamoulian and take over the production himself. Approving Preminger’s takeover was a risky move on Zanuck’s part. Preminger had not yet developed into the autocrat behind the camera that he would eventually become; his output to this point consisted of a few “B” movies. And yet, after Laura, for which he would earn his first of three Oscar nominations for Best Director, he became one of Fox’s most important and edgy sources of film noir in the 1940s and 1950s. He followed it with Fallen Angel (1945), Whirlpool (1950), and Angel Face (1953), among others.

In her 1979 autobiography, Self-Portrait, Tierney noted feeling unmoved by the part: “The time on camera was less than one would like. And who wants to play a painting?” Perhaps she resented playing a character who had no agency and whose image was obsessed over by others. Ever since director Anatole Litvak first spotted the 17-year-old Tierney on the Warner Bros. lot with her parents and ordered her a screen test, she was an object of desire. After that moment, the Hollywood career she so desired would slowly destroy her. When she finally signed a contract with Fox, they instructed her to start smoking to lower her voice. Years later, she would die of emphysema from her smoking habit. In the meantime, the stress of preserving her star image weighed on her. She was forced into a restrictive diet that she begrudgingly followed for twenty years. She also had a family to support: an ailing mother; the wavering fashion design business started by her husband, Oleg Cassini; and the trauma of her first child—who was born deaf, with partial blindness and severe intellectual disabilities. In another tragic irony of Tierney’s celebrity shaping her life, she later learned that her daughter’s conditions resulted from the actress contracting the German Measles from an enthusiastic fan who left quarantine to meet her.

In her 1979 autobiography, Self-Portrait, Tierney noted feeling unmoved by the part: “The time on camera was less than one would like. And who wants to play a painting?” Perhaps she resented playing a character who had no agency and whose image was obsessed over by others. Ever since director Anatole Litvak first spotted the 17-year-old Tierney on the Warner Bros. lot with her parents and ordered her a screen test, she was an object of desire. After that moment, the Hollywood career she so desired would slowly destroy her. When she finally signed a contract with Fox, they instructed her to start smoking to lower her voice. Years later, she would die of emphysema from her smoking habit. In the meantime, the stress of preserving her star image weighed on her. She was forced into a restrictive diet that she begrudgingly followed for twenty years. She also had a family to support: an ailing mother; the wavering fashion design business started by her husband, Oleg Cassini; and the trauma of her first child—who was born deaf, with partial blindness and severe intellectual disabilities. In another tragic irony of Tierney’s celebrity shaping her life, she later learned that her daughter’s conditions resulted from the actress contracting the German Measles from an enthusiastic fan who left quarantine to meet her.

With pressures mounting in Tierney’s personal life, she needed roles like Laura Hunt, even if she thought little of them. “Really, I was in no position to be picky,” she wrote. Even after her career bloomed with roles in Leave Her to Heaven (1945), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), and Night and the City (1950), she continued to struggle in Hollywood. By the age of 34, Tierney was not only physically transformed by Hollywood but her mental state became increasingly fragile. Stress, depression, an undiagnosed bipolar disorder, and guilt over her first daughter’s institutionalization took their toll. She underwent psychotherapy and shock treatments. Between institutionalizations, she considered suicide when she stepped out onto the ledge of her New York apartment before a crowd of onlookers, among them her second daughter. Eventually, she retreated from the public eye to look after her mental health at a clinic in Topeka, Kansas, where she was advised to take a sales position in a local shop to adjust to people again. She was soon recognized and pestered by reporters while at work; the story made headlines, and Tierney was forced to quit her job. By the early 1950s, her film roles became intermittent. Within a few years, she retired from Hollywood and lived out her remaining decades with a quiet life in Houston.

Besides Tierney—who hadn’t revealed her full potential by 1944—Laura is full of unlikely casting choices. There’s Dana Andrews, an unproven “B” actor with few credits; he would soon become a film noir staple and make four more films with Preminger. Price is memorable as Laura’s husband-to-be, a far slipperier character than the types of intimidating roles he would take in Roger Corman and William Castle’s films. And while Judith Anderson’s role as Laura’s wealthy aunt isn’t as iconic as her Mrs. Danvers from Rebecca (1940), she delivers a complex character that this essay will touch on later. Then there is queer icon Clifton Webb, a Broadway star who had not appeared in a film since 1930. Webb was championed by Preminger, despite warnings to Zanuck that “he flies”—a reference to Webb’s sexuality. Noir scholar James Naremore observed wryly that Laura bears a camp quality given these actors who invite “a mood of fey theatricality.” But only in retrospect, when viewing Anderson’s closeted lesbian role in Rebecca, Price’s bisexuality as an open secret in Hollywood, and Webb’s open homosexuality, does Laura play as Naremore suggests.

On the surface, Laura doesn’t offer outright queer characters or even readable subtexts. Though, it’s easy to call Lydecker characteristic of classic Hollywood’s long line of effeminate villains, such as Claude Rains in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) or Farley Granger and John Dall in Rope (1948). Note the scene when Lydecker first meets McPherson. He sits in the tub—not nude as some have noted but in trunks, and evoking Dalton Trumbo—and stands before asking McPherson to hand him a robe. But it hardly feels like a come-on, as some have suggested. Perhaps Lydecker intended the moment as a power grab, forcing McPherson to feel intimidated by a naked (or mostly naked) man. Or maybe he’s trying to distract from his guilt. “How singularly innocent I look this morning,” he reflects as only a guilty man would. “Have you ever seen such candid eyes?” Then again, perhaps viewers have projected on Lydecker what they know about Webb. As we will see later, Lydecker remains obsessed with Laura to such an extent that it drives him to murder. His acidic, egomaniacal, and what some might call stereotypically bitchy characterization gives Laura its sharp wit and darkly comic appeal, carried by an egoist who believes “in my case, self-absorption is completely justified” and “I’m not kind. I’m vicious. It’s the secret of my charm.”

On the surface, Laura doesn’t offer outright queer characters or even readable subtexts. Though, it’s easy to call Lydecker characteristic of classic Hollywood’s long line of effeminate villains, such as Claude Rains in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) or Farley Granger and John Dall in Rope (1948). Note the scene when Lydecker first meets McPherson. He sits in the tub—not nude as some have noted but in trunks, and evoking Dalton Trumbo—and stands before asking McPherson to hand him a robe. But it hardly feels like a come-on, as some have suggested. Perhaps Lydecker intended the moment as a power grab, forcing McPherson to feel intimidated by a naked (or mostly naked) man. Or maybe he’s trying to distract from his guilt. “How singularly innocent I look this morning,” he reflects as only a guilty man would. “Have you ever seen such candid eyes?” Then again, perhaps viewers have projected on Lydecker what they know about Webb. As we will see later, Lydecker remains obsessed with Laura to such an extent that it drives him to murder. His acidic, egomaniacal, and what some might call stereotypically bitchy characterization gives Laura its sharp wit and darkly comic appeal, carried by an egoist who believes “in my case, self-absorption is completely justified” and “I’m not kind. I’m vicious. It’s the secret of my charm.”

Visually, Preminger’s approach to Laura proves static and detached, especially when compared to his later work. But this is purposeful. Using plan américain photography shot by cinematographer Joseph LaShelle, Preminger captures characters in profile as they discuss their motives and alibis. Rather than cutting a scene down in a two-shot structure, alternating between McPherson’s question and the suspect’s answer, he allows us to observe them from an objective vantage point and judge their behavior. In larger settings, Preminger employs whip pans to transition from one character to the next, which allows for movement without telling the viewer where to look or how to feel about the characters. As a result, Laura’s cinematography sometimes feels impersonal, as though the visuals give the viewer no clear indication about where our sympathy should lie. Moreover, much of the film’s action unfolds in well-lit interiors—Laura’s apartment above all—far removed from the moody shadows and expressive camera angles commonly found in film noir. Alternatively, David Raskin’s score accounts for much of Laura’s noir flavor; it haunts the film like the idea of Laura haunts other characters. Written after receiving a Dear John letter from his wife, the music became a best-selling standard recorded by names like Nat King Cole, Charlie Parker, and Frank Sinatra. Raskin’s melancholy notes build substance into the affections, memories, and obsessions that turn into murderous impulses, tonally situating Laura into the film noir genre.

While Laura is often lumped into this stylized genre because of certain plot elements and its score, the film lacks many of the common characteristics associated with film noir. Perhaps if Laura had murdered Diane Redfern out of jealousy or, say, pinned the murder on Lydecker or Carpenter to escape their hold, then she would have been an archetypal femme fatale. As is, she remains wrongly accused, if central to the motivations of other characters. But she is hardly the duplicitous, seductive, and amoral woman often featured in film noirs. Further, McPherson isn’t the shady cop found in so many genre offerings. As far as we can tell, he is a decent detective with one central flaw: he allows himself to be emotionally invested in the case—a condition the story rewards when it hints that McPherson and Laura will end up together. If McPherson’s fixation had been a punishable moral crime in the film’s eyes, or those of the Production Code, there might have been another scene showing him reprimanded or Laura turning him down romantically. Instead, we believe they will end up together because the film believes his obsession is justified and his love is true. To be sure, there have been far more corrupted noir protagonists who walk the line between hero and antihero. Take Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), where Andrews again plays a cop, but this time he goes to prison for killing a suspect while questioning him.

However, almost every character in Laura is capable of, shall we say, moral flexibility. Each of them exists in varying shades of gray. There’s Ann Treadwell, Laura’s aunt, who offers honest self-appraisal in her speech explaining why she and Carpenter belong together: “He’s no good but he’s what I want. […] We belong together because we’re both weak and can’t seem to help it. That’s why I know he’s capable of murder; he’s like me.” Each character is driven toward their singular desire—which is usually Laura—except in Ann’s case. Even Bessie hides important evidence because she worries that it might reflect poorly on Laura. Meanwhile, no one cares about poor Miss Redfern—not even Carpenter, who, we must assume, was having an affair with her. And while this general atmosphere of moral ambivalence makes Laura a film noir, the climax’s plot mechanics help as well. Taking a cue from the Thin Man series, McPherson gathers all suspects at a party and proceeds to make a show of identifying his prime suspect. Outwardly, he pins the murder on Laura, but it’s a ruse to expose the real killer: Lydecker, whose jealous brand of “If I can’t have you, no one will” logic has driven him to murder.

However, almost every character in Laura is capable of, shall we say, moral flexibility. Each of them exists in varying shades of gray. There’s Ann Treadwell, Laura’s aunt, who offers honest self-appraisal in her speech explaining why she and Carpenter belong together: “He’s no good but he’s what I want. […] We belong together because we’re both weak and can’t seem to help it. That’s why I know he’s capable of murder; he’s like me.” Each character is driven toward their singular desire—which is usually Laura—except in Ann’s case. Even Bessie hides important evidence because she worries that it might reflect poorly on Laura. Meanwhile, no one cares about poor Miss Redfern—not even Carpenter, who, we must assume, was having an affair with her. And while this general atmosphere of moral ambivalence makes Laura a film noir, the climax’s plot mechanics help as well. Taking a cue from the Thin Man series, McPherson gathers all suspects at a party and proceeds to make a show of identifying his prime suspect. Outwardly, he pins the murder on Laura, but it’s a ruse to expose the real killer: Lydecker, whose jealous brand of “If I can’t have you, no one will” logic has driven him to murder.

Though every character has their motivations, none is more obsessed than Lydecker, who cuts Laura down in their first introduction and builds her up again in his image. “Laura had innate breeding,” he explains to McPherson. “But she deferred to my judgment and taste. I selected a more attractive hairdress for her. I taught her what clothes were more becoming to her. Through me, she met everyone—the famous and the infamous.” Anticipating James Stewart’s Scottie in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), Lydecker demonstrates the textbook behaviors of a stalker or controlling lover: he follows her, finds excuses to stroll past her apartment, showers her with attention and gifts, but he also expects her to conform to his idea of her. Laura’s willingness to bend to his vision feeds his ego, his only true love. Based in part on the famously snobby New Yorker theater critic Alexander Woollcott, Lydecker’s colorfully violent language in the screenplay (“If you come a little closer, my boy, I can crack your skull”) hints at his capacity for murder. In the end, Lydecker’s spell over Laura is broken. The film’s last shot rests on the clock Lydecker gave her, identical to one in his own apartment of course. Lydecker shatters it when he shoots at Laura and misses, just as officers gun him down. The symbol of Lydecker’s hold over Laura is destroyed.

Tierney was subject to a similar brand of destructive obsession in her life and career, and one wonders whether she made the connection between the character and herself. Critics, above all in The New York Times, often wrote about Tierney in terms of her appearance and regularly called out her surface beauty, privileged upbringing, and role as a debutante. A review of Bell Star (1941), in which she plays the title role of an American outlaw, notes that “her youth and fancy finishing school background betray her.” The review of Laura was just as unkind, stating Tierney “simply doesn’t measure up to the word-portrait of her character. Pretty, indeed, but hardly the type of girl we had expected to meet. For Miss Tierney plays at being a brilliant and sophisticated advertising executive with the wild-eyed innocence of a college junior.” More recent appraisals have acknowledged that Laura isn’t Tierney’s best performance. Roger Ebert was right when he observed that Tierney “never seems emotionally involved” in her role. Then again, perhaps Preminger intended Tierney to appear detached. Laura remains a character whose identity is assumed and assigned by those who regard her or her portrait. She’s almost as absent from the picture as the titular character from Hitchcock’s Rebecca, which charts the lingering impact of a woman’s memory.

Laura is a beautiful portrait, an image onto which, like Lydecker, Carpenter, and McPherson, the viewer projects meaning. Preminger and Tierney create a character whose beauty, success, and sophistication become surface traits that reduce Laura to a concept more than a flesh and blood human being. But as Laura transitions from a film noir charting a murder investigation during the first half, it centers us in the midst of a romantic mystery during the second half. McPherson, thus the viewer, like the others, has fallen for the fantasized idea of Laura, even as the character herself—her personality, her tastes, her sense of humor—remain elusive and undefined. Sadly, then, Laura, a film about how fantasies build up, blur, and dehumanize one woman, provides a lens through which we can understand Tierney’s life as a celebrity. Tierney gave a more nuanced performance in Leave Her to Heaven and a more affecting turn in Night and the City, but her presence haunts Laura well beyond the final shot. Onscreen, Tierney plays an icon who entrances everyone around her, but the performer’s life off-camera lends the role tragic insight that makes the film unforgettable.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Devil Made It? Ballantine, 1997.

Hirsch, Foster. Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would be King. Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Janovich, Mark. “‘Vicious Womanhood’: Genre, the ‘Femme Fatale’ and Postwar America.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 2011, pp. 100–114. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24411857. Accessed 1 May 2021.

McNamara, Eugene. “Laura” as Novel, Film, and Myth. Edwin Mellen Press, 1992.

Naremore, James. “American Film Noir: The History of an Idea.” Film Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 1995, pp. 12–28. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1213310. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Tierney, Gene. Self-Portrait. Wyden Books, 1979.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review