The Definitives

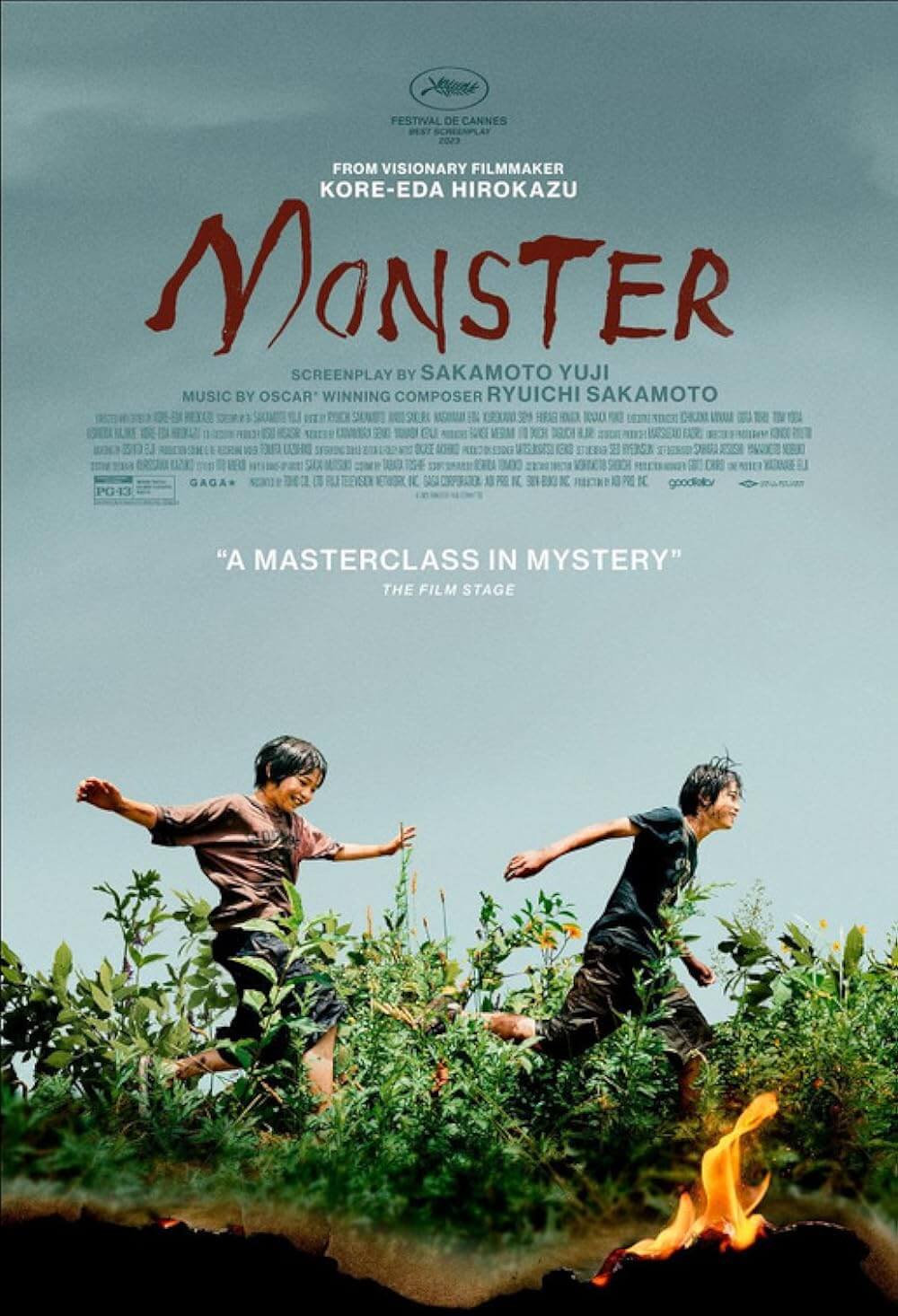

La strada (1954)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Before Federico Fellini became the world-renowned fabulist of European cinema; before he was celebrated for autobiographical exhibitions into his fantasies, sexuality, religion, and memory; before his name inspired the new adjective “Felliniesque” and therein cemented his international celebrity; before all of this, the Italian filmmaker made La strada (The Road). After the film’s release in 1954—as well as subsequent films like La dolce vita (1960), 8 ½ (1963), and Amarcord (1973)—Fellini’s name would be synonymous with such characteristics, which would popularize and sanctify his persona and films until the end of his career. La strada marked his first wholly Felliniesque picture, wherein his boundless formal and narrative energy are married to his ability to capture reality and reflect its truth through his dreamlike perspective—the mark of a true artist and poet. Fellini’s films would continue to reflect his own reality, resulting in a dizzying combination of personal influences. But his style never had greater dramatic effect than in La strada, which combines the director’s roots in neorealism; his affinity for variety shows, circus acts, and parades; and more than his later, increasingly fanciful work, the film embraces a tragic, almost lyrical, if not mythical romanticism that imparts it with a sense of timelessness.

As the legend goes, Federico Fellini was born on a moving train in 1920. The train headed through his hometown of Rimini, where his father Urbano, a traveling salesman, and mother Ida raised him. Though subsequently dispelled by Fellini biographer Tullio Kezich, the story stuck with Fellini for the rest of his life, perhaps because he never settled. He held meetings in cars and pushed himself with a tireless energy, eating rigorously and enjoying the company of countless women, so it only seemed fitting that he was born on a train. Like many great filmmakers, myth surrounds Fellini. To siphon through the myth and get to the root of his character is much easier than charting his factual history in a biographical text—quite simply because he has left behind a self-acknowledged autobiographical opus. Kezich wrote, “Cinema resolves one of the contradictions in Fellini’s character, reconciling his constant need to escape—anywhere—with his ethical imperative to do something he can call his own. Fundamentally cinema was a way to avoid familial and social obligations while expressing himself, like cutting school in order to recognize what was important.” In other words, if you were to ask Fellini about his life, he might say it’s up there on the screen. Consider, for example, Fellini’s initial career ambitions. He wanted to be either a painter or a journalist, two oppositional philosophies whereby, most idealistically, one documents the world, and the other reinterprets it through brushstrokes. He demonstrates an interest in the real world, but he also wants to make that world his own.

Fellini was somewhere in-between reality and a cartoon. He reached adulthood during the emergence of World War II, his existence consumed by a horrible reality all around him. And yet, for one of his earliest jobs, he chose to represent the world through caricature, creating sketches and cartoons for his own caricature shop. Later, he wrote gags and whole scenarios for filmmakers, often comical or fanciful. He also wrote a popular column for the magazine Marc’Aurelio, then wrote for radio and took several uncredited screenplay gigs. By the mid-1940s, emergent neorealist director Roberto Rossellini had taken Fellini under his wing. Many other Italian filmmakers joined Rossellini’s neorealism movement, which sought to refocus the lens of postwar Italian cinema on the working class. They shot on real locations and used unknown actors. Fellini co-wrote the neorealist movement’s first major effort, Rome, Open City (1945), and he served as assistant director on Paisà in 1946, also under Rossellini. Not until 1950 and 1951 would Fellini move on to his own directorial projects, Variety Lights and The White Sheik, respectively. The following year he received the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion award for I vitelloni. But not until La strada did all of Fellini’s cinematic faculties blossom and realize their full collaborative potential. Fellini finally became a highly individualized, stylized, and personal filmmaker in 1954.

Fellini was somewhere in-between reality and a cartoon. He reached adulthood during the emergence of World War II, his existence consumed by a horrible reality all around him. And yet, for one of his earliest jobs, he chose to represent the world through caricature, creating sketches and cartoons for his own caricature shop. Later, he wrote gags and whole scenarios for filmmakers, often comical or fanciful. He also wrote a popular column for the magazine Marc’Aurelio, then wrote for radio and took several uncredited screenplay gigs. By the mid-1940s, emergent neorealist director Roberto Rossellini had taken Fellini under his wing. Many other Italian filmmakers joined Rossellini’s neorealism movement, which sought to refocus the lens of postwar Italian cinema on the working class. They shot on real locations and used unknown actors. Fellini co-wrote the neorealist movement’s first major effort, Rome, Open City (1945), and he served as assistant director on Paisà in 1946, also under Rossellini. Not until 1950 and 1951 would Fellini move on to his own directorial projects, Variety Lights and The White Sheik, respectively. The following year he received the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion award for I vitelloni. But not until La strada did all of Fellini’s cinematic faculties blossom and realize their full collaborative potential. Fellini finally became a highly individualized, stylized, and personal filmmaker in 1954.

After the release and huge success of I vitelloni, Fellini was being pressured to direct a sequel; he even wrote a sequel script, but his passions lie elsewhere. In the early 1950s, Fellini began to understand the power of cinema as a device of expression, and he became obsessed with the notion of exacting his precise expression on his audience. Signs of his famous Machiavellian behavior on-set emerged in behind-the-scenes stories. The maestro demanded absolute control over every aspect of his production, behaving like an impetuous teen to get his way. He was known for shouting his directorial orders, and he set up his producers as though they were father figures against whom he would battle and defy. He defended and fought for every artistic impulse. But La strada would be his first real chance to embrace his every whim and indulgence. As early as 1951, Fellini and his co-writer Tuillo Finelli sought to write something about a “traveling party” of vagabonds and circus types. Their writing lasted for another two years until pre-production on La strada finally began in 1953. Dino de Laurentiis served as the producer but voiced his disapproval of the downtrodden story; he wanted a Hollywood ending. For Fellini, this was proof that de Laurentiis did not understand the project. But as with most of his producers, Fellini did not need de Laurentiis to understand the film; he just needed him to support it with his money and influence. Nevertheless, the battles between Fellini and de Laurentiis over the film’s ending would continue throughout production, which began in October 1953 and lasted until the following spring.

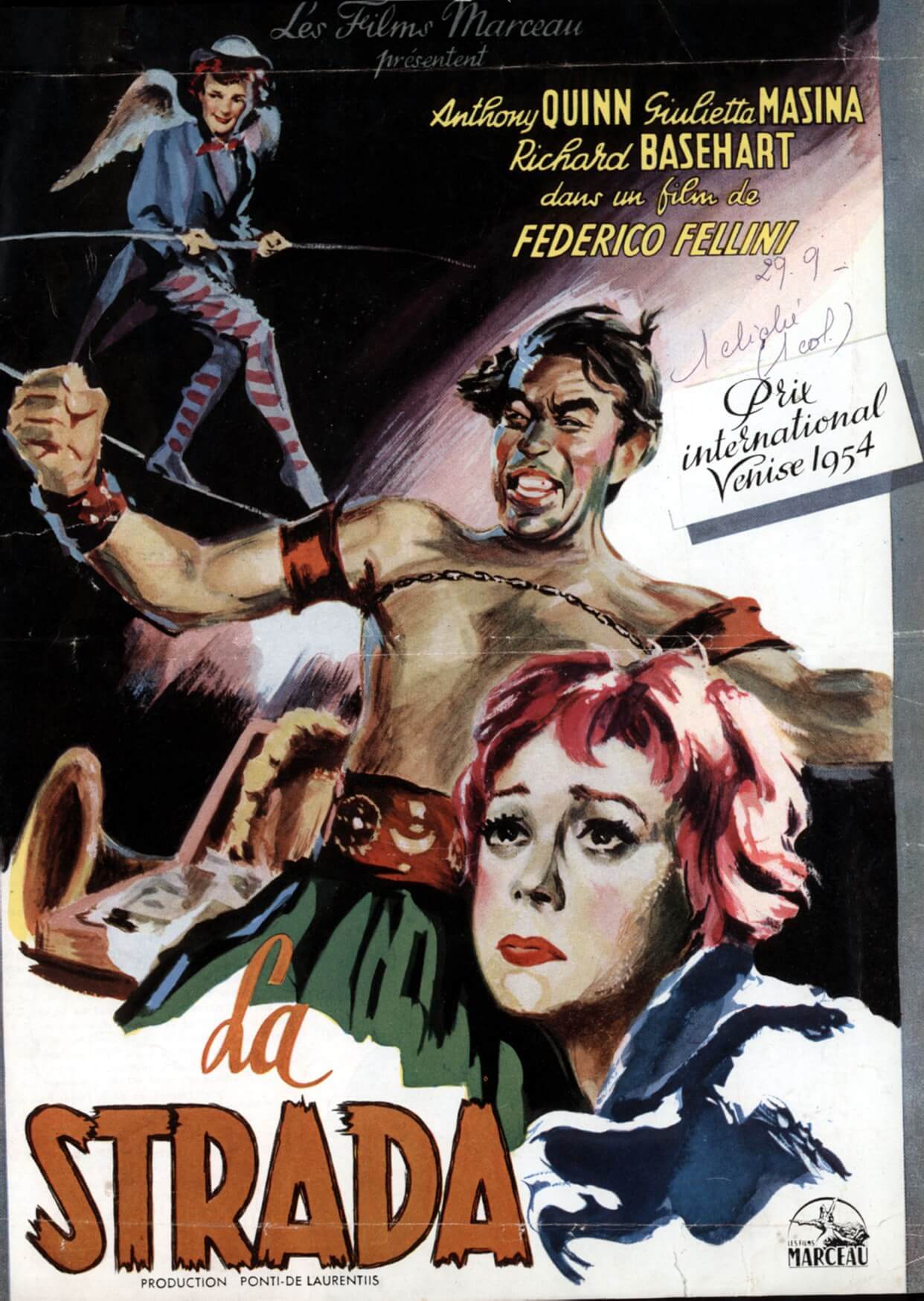

The story opens with Gelsomina, a young woman who, like her late sister before her, is sold to the traveling performer Zampanò for 10,000 lire. The deal’s broker, Gelsomina’s mother, warns Zampanò that Gelsomina “came out strange,” and sure enough, she proves a little odd. Together, the new couple takes to the road where Zampanò performs a strongman act and breaks an iron chain with his pectorals. He teaches Gelsomina drumroll and clown routines for his act, shows her how to cook and clean up their live-in cart, and forces her into bed. After their first night together, she wakes up to tears, wipes them away, smiles at her new companion, and then wipes away more tears. Her life with Zampanò continues like this with cruelties abound, suffering his dominion endlessly. Still, she remains devoted to him even though she despises her mistreatment and tries to leave more than once; she always seems to find her way back under Zampanò’s wing. On the road, they meet a clown and high-wire walker called Il Matto (the fool), whose sprightly energy charms her. Il Matto tries to tell Gelsomina to trust that her life has meaning, and in turn, she projects that meaning onto Zampanò and pledges her devotion to him. Meanwhile, Il Matto admits he has an uncontrollable desire to aggravate Zampanò. The clown’s prodding eventually results in his death when the strongman kills him in a fight. At this, Gelsomina loses herself in an almost catatonic sadness, as Il Matto’s death represents a final unforgivable act on Zampanò’s part. Ashamed and unable to shake Gelsomina out of her depression, Zampanò abandons her. Some years later, he learns that she died of her sadness; only then does the man’s regret consume him.

The story opens with Gelsomina, a young woman who, like her late sister before her, is sold to the traveling performer Zampanò for 10,000 lire. The deal’s broker, Gelsomina’s mother, warns Zampanò that Gelsomina “came out strange,” and sure enough, she proves a little odd. Together, the new couple takes to the road where Zampanò performs a strongman act and breaks an iron chain with his pectorals. He teaches Gelsomina drumroll and clown routines for his act, shows her how to cook and clean up their live-in cart, and forces her into bed. After their first night together, she wakes up to tears, wipes them away, smiles at her new companion, and then wipes away more tears. Her life with Zampanò continues like this with cruelties abound, suffering his dominion endlessly. Still, she remains devoted to him even though she despises her mistreatment and tries to leave more than once; she always seems to find her way back under Zampanò’s wing. On the road, they meet a clown and high-wire walker called Il Matto (the fool), whose sprightly energy charms her. Il Matto tries to tell Gelsomina to trust that her life has meaning, and in turn, she projects that meaning onto Zampanò and pledges her devotion to him. Meanwhile, Il Matto admits he has an uncontrollable desire to aggravate Zampanò. The clown’s prodding eventually results in his death when the strongman kills him in a fight. At this, Gelsomina loses herself in an almost catatonic sadness, as Il Matto’s death represents a final unforgivable act on Zampanò’s part. Ashamed and unable to shake Gelsomina out of her depression, Zampanò abandons her. Some years later, he learns that she died of her sadness; only then does the man’s regret consume him.

Fellini found most of his players, including Mexican star Anthony Quinn, while visiting the set of another film, Giuseppe Amato’s Donne proibite (Angels of Darkness, 1953). Of course, de Laurentiis wanted bankable actors such as Burt Lancaster and Silvana Mangano in the lead roles, but the director’s mind was already made up. Though Fellini and Quinn were not familiar with one another, the director knew Quinn’s strong, masculine features were just what his Zampanò needed. Initially, Quinn showed no interest in the story, and dismissively described it as “something about a strongman and a half-witted girl.” But Fellini hounded the actor for weeks. Quinn later remembered, “I thought he was a little bit crazy.” Only after, somewhat reluctantly, Quinn allowed Fellini to screen I vitelloni for him did the actor sign to star. For Il Matto, Fellini sought American actor Richard Basehart, who was then living in Rome and had impressed Fellini with his performance in Fourteen Hours (1951)—where his character stands on a ledge, contemplating suicide for the film’s duration. When Basehart asked Fellini why the director would choose him of all people to play a clown, Fellini replied, “If you did what you did in Fourteen Hours, you can do anything.” And for Gelsomina, there was never anyone on Fellini’s mind other than his own wife since 1943, the beautiful and charming Giulietta Masina. However, Fellini had to fight with producers to cast Masina; they still saw her as the downtrodden whore from Senza pietà (Without Pity, 1948).

Although filming began in late 1953, production halted when Masina dislocated her ankle and delayed the overall schedule. Because Quinn had obligations to another project—playing Attila the Hun in de Laurentiis’s production of Attila for director Pietro Francisci—Fellini’s shoot had to accommodate. The director had access to Quinn in the morning, but by Noon, the actor would have to rush to the Attila set. To prepare, Quinn and Fellini learned everything they could from Savitri, a real-life strongman and circus performer who ate fire and broke chains. Fellini sought authenticity for his circus, so production supervisor Luigi Giacosi rented Savitri’s small circus, including tents and caravans. Giacosi was famous for procuring anything Fellini needed, and the director often tested Giacosi’s skill. Take the time when Fellini arrived on-set and shouted out, “Where’s the elephant?” as a test. At this, Giacosi disappeared for a short time and returned an hour later with an elephant in tow. When there was no snow for wintry mountain scenes, Giacosi used white linens and thirty bags of plaster to create the appropriate look. As for the shoot, Fellini had prepared meticulously and demonstrated a fervor he had never experienced before. He filled his shooting script with notes about camera angles, period research, set descriptions, and dialogue. Though La strada‘s runtime would be only 104 minutes, Fellini’s script was 600 pages. He put so much into the film that three weeks before shooting wrapped in May 1954, the director of seemingly limitless energy collapsed from fatigue.

Although filming began in late 1953, production halted when Masina dislocated her ankle and delayed the overall schedule. Because Quinn had obligations to another project—playing Attila the Hun in de Laurentiis’s production of Attila for director Pietro Francisci—Fellini’s shoot had to accommodate. The director had access to Quinn in the morning, but by Noon, the actor would have to rush to the Attila set. To prepare, Quinn and Fellini learned everything they could from Savitri, a real-life strongman and circus performer who ate fire and broke chains. Fellini sought authenticity for his circus, so production supervisor Luigi Giacosi rented Savitri’s small circus, including tents and caravans. Giacosi was famous for procuring anything Fellini needed, and the director often tested Giacosi’s skill. Take the time when Fellini arrived on-set and shouted out, “Where’s the elephant?” as a test. At this, Giacosi disappeared for a short time and returned an hour later with an elephant in tow. When there was no snow for wintry mountain scenes, Giacosi used white linens and thirty bags of plaster to create the appropriate look. As for the shoot, Fellini had prepared meticulously and demonstrated a fervor he had never experienced before. He filled his shooting script with notes about camera angles, period research, set descriptions, and dialogue. Though La strada‘s runtime would be only 104 minutes, Fellini’s script was 600 pages. He put so much into the film that three weeks before shooting wrapped in May 1954, the director of seemingly limitless energy collapsed from fatigue.

La strada premiered at the Venice Film Festival on September 6, 1954, and the festival’s panel of judges struggled to pick their Golden Lion winner. In the postwar environment, something as spiritualist as La strada would have been a political choice for the panel, as would a competitor like Luchino Visconti’s Senso, because of Visconti’s Communist sympathies. Instead, the panel awarded a safer choice the Golden Lion, Renato Castellani’s Romeo and Juliet, and gave La strada the second-place Silver Lion (that year, the Silver Lion was also awarded to Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff, and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront). The critical reception of La strada in Italy was, in large part, shaped by the country’s fascination with neorealism and what were perceived to be Fellini’s intentions with the film. Because Fellini refuses to spell out his film’s themes and meaning, Visconti described it as “neo-abstractionism.” Critics such as Guido Aristarco and Arturo Lanocita considered the film too vague or ideologically misguided in its sense of Christian forgiveness and redemption. Italian critics in artistic circles praised the film, but mainstream audiences had contrasting opinions, calling it unrealistic, naïve, and too clever for its own good. Perhaps Italian critics failed to understand the film because it was something new—pure Fellini. Elsewhere, Italian cinema, which French critics had somewhat ignored since the advent of neorealism, was suddenly reconsidered by Cahiers du cinéma critic Dominique Aubier in 1955. Aubier wrote that the film belongs to a “mythological class.” Indeed, La strada would go on to earn upwards of 50 awards internationally over the next several years, not the least of which was the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 1957.

Many viewers of the period, and many still today, found the story to be simple, perhaps because Gelsomina appears to be as dim-witted as her mother describes. Others find La strada to be a portrait of marriage in a pre-feminist age—an interpretation that Fellini later disagreed with openly and despised. But this is a deceptively simple film. Though during its initial release, Fellini told an interviewer, “This is what most marriages are like,” the director later claimed that his intention was not to paint every marriage as a relationship between a brutal husband and a humiliated wife. Rather, Fellini went back to his own parents’ marriage, where, much like Zampanò and Gelsomina, his father was an abusive extrovert and traveled in his work, while his mother “consoled” herself inwardly. In this interpretation, Masina plays not only Fellini’s mother but also the director himself—because as a child, Fellini also left home, joined the circus, and dreamt his way through life by reflecting on his own fantasies and impressions of the world at large. The thought that La strada is somehow pre-feminist becomes absurd when one considers how completely Fellini put himself into the Gelsomina character, making her sad existence and death the apex of the film’s tragedy. There are few scenes more heartbreaking in cinema than when, traumatized by Il Matto’s death, Gelsomina curls up on a blanket in the cold outdoors, like a sick dog that crawls under the porch to die, and Zampanò lets her. Our resounding empathy for Gelsomina, along with the understanding that, to be sure, Zampanò was a cruel and later regretful companion, saturates the picture’s soul.

Many viewers of the period, and many still today, found the story to be simple, perhaps because Gelsomina appears to be as dim-witted as her mother describes. Others find La strada to be a portrait of marriage in a pre-feminist age—an interpretation that Fellini later disagreed with openly and despised. But this is a deceptively simple film. Though during its initial release, Fellini told an interviewer, “This is what most marriages are like,” the director later claimed that his intention was not to paint every marriage as a relationship between a brutal husband and a humiliated wife. Rather, Fellini went back to his own parents’ marriage, where, much like Zampanò and Gelsomina, his father was an abusive extrovert and traveled in his work, while his mother “consoled” herself inwardly. In this interpretation, Masina plays not only Fellini’s mother but also the director himself—because as a child, Fellini also left home, joined the circus, and dreamt his way through life by reflecting on his own fantasies and impressions of the world at large. The thought that La strada is somehow pre-feminist becomes absurd when one considers how completely Fellini put himself into the Gelsomina character, making her sad existence and death the apex of the film’s tragedy. There are few scenes more heartbreaking in cinema than when, traumatized by Il Matto’s death, Gelsomina curls up on a blanket in the cold outdoors, like a sick dog that crawls under the porch to die, and Zampanò lets her. Our resounding empathy for Gelsomina, along with the understanding that, to be sure, Zampanò was a cruel and later regretful companion, saturates the picture’s soul.

Throughout the course of the film, Gelsomina could leave Zampanò several times, but she does not; instead, she repeatedly suffers his infidelities and abuse. She could have left him after the wedding at the farmhouse, where Zampanò spends the night with the materfamilias; she could have left after he runs off to bed a local tart in the village; she could have joined up with the large traveling circus that Zampanò refused to join; she could have left after Zampanò goes to jail for chasing Il Matto with a knife; and she could have stayed at the convent, where the nuns would have taken care of her. But like a nun, she devotes herself to her cause. Perhaps she stays with Zampanò because she feels she does not belong anywhere else, or perhaps because no woman in her right mind would stay with a man like this (and Gelsomina is not a woman in her right mind). When Il Matto asks her why she stays, she does not know. “If I don’t stay with him, who will?” Finally, she finds a sad kind of rationale to her life with Zampanò, as Il Matto explains that everything has a purpose, even a pebble. Her life is equal to that of a meaningless grain of sand; she finds a pathetic but no less endearing philosophy to her existence. And yet, even this wholly minute justification is betrayed by Zampanò, making her what author Angelo Solmi called “a martyr to loneliness.”

At the time of its release, most critics in Italy met Fellini’s soulful intentions with disdain, and their assessments split between Marxist and Catholic ideologies. Marxist doctrines demanded realism in the postwar climate so as not to embrace the damnable prewar individualism that led to World War II. Marxist forerunner Guido Aristarco condemned La strada, claiming it “gathered up and jealously preserved the subtlest poisons of the prewar literature.” And though Catholics did not denounce the film, their interpretation was just as misguided. In a Catholic interpretation, Il Matto is likened to Christ, and because Zampanò ostensibly kills Christ, Gelsomina cannot forgive him. The parallel allows for Christian love and eventually deliverance through repentance but does not explain why Il Matto endlessly pesters Zampanò. In other circles, the film was interpreted as a naturalist metaphor, wherein Il Matto represents the mind, Zampanò represents the body, and Gelsomina represents the soul. In response to Aristarco and other circles who misinterpreted the film, Fellini wrote a letter published in Il Contemporaneo called Letter to a Marxist, where he wrote, “Because [La strada] tries to show the supernatural and personal communication between a man and a woman who would seem by nature to be the least likely people to understand each other, it has, I believe, been attacked by those who believe only in natural and political communication.” Fellini’s brand of artistic expression from La strada onward would be rooted in the autobiographical and poetic, which was somewhat oppositional to Italian postwar cinema. Looking over Fellini’s statements about the film as the critical debate rages on even today, it becomes evident that perhaps Fellini did not know what the film would mean to anyone else but himself. As Fellini later explored in 8 ½, the director admittedly does not always know what he wants or how to achieve it, yet somehow he always has the capacity to deliver something that evokes a range of emotional responses.

At the time of its release, most critics in Italy met Fellini’s soulful intentions with disdain, and their assessments split between Marxist and Catholic ideologies. Marxist doctrines demanded realism in the postwar climate so as not to embrace the damnable prewar individualism that led to World War II. Marxist forerunner Guido Aristarco condemned La strada, claiming it “gathered up and jealously preserved the subtlest poisons of the prewar literature.” And though Catholics did not denounce the film, their interpretation was just as misguided. In a Catholic interpretation, Il Matto is likened to Christ, and because Zampanò ostensibly kills Christ, Gelsomina cannot forgive him. The parallel allows for Christian love and eventually deliverance through repentance but does not explain why Il Matto endlessly pesters Zampanò. In other circles, the film was interpreted as a naturalist metaphor, wherein Il Matto represents the mind, Zampanò represents the body, and Gelsomina represents the soul. In response to Aristarco and other circles who misinterpreted the film, Fellini wrote a letter published in Il Contemporaneo called Letter to a Marxist, where he wrote, “Because [La strada] tries to show the supernatural and personal communication between a man and a woman who would seem by nature to be the least likely people to understand each other, it has, I believe, been attacked by those who believe only in natural and political communication.” Fellini’s brand of artistic expression from La strada onward would be rooted in the autobiographical and poetic, which was somewhat oppositional to Italian postwar cinema. Looking over Fellini’s statements about the film as the critical debate rages on even today, it becomes evident that perhaps Fellini did not know what the film would mean to anyone else but himself. As Fellini later explored in 8 ½, the director admittedly does not always know what he wants or how to achieve it, yet somehow he always has the capacity to deliver something that evokes a range of emotional responses.

By that logic, La strada’s purpose or message may seem elusive, but it is no less profoundly affecting. It remains an incredibly lyrical and marvelously acted film, especially on Masina’s part. And though the music of Nino Rota brings the picture together with a combination of tender notes and circus melodies, the heart of the film can be found on Masina’s face. Her round, expressive eyes seem to hold in them all the wonder and sadness of the world. She delivers Gelsomina’s sulking, almost cartoonish glower in aching pangs, whereas her conditional smile is enough to bring a viewer to tears. Fellini saw Gelsomina as a fighter, someone who endures her harsh reality by escaping into her mind; the director’s perspective was decidedly male, once describing the film as “the story of a man who discovers himself,” and doing so only after recognizing his own punishing treatment Gelsomina. Masina saw her character differently, more like an ill-fated Cinderella. And perhaps that is the best way to describe Masina’s fascinating, intricate performance. Gelsomina remains hopeful about Zampanò—that somehow he will transform into a Prince Charming and live up to her romantic ideas about companionship. Despite his abuses and her wretched existence, she wants to love him and be loved. That she is a little “strange” does not imply that she has some mental disability and therefore remains unrelatable (Roger Ebert suggested, quite offensively, that she suffers from “retardation”). Perhaps it is the naiveté, blind optimism, and purity of emotions that Masina projects that make her character strange in an otherwise cynical, impure world.

Or perhaps Masina taps into our cinematic memory to charm us. When Zampanò first gives Gelsomina her costume for their act, he hands her a pile of clothes—an oversized coat and a bowler hat, both best suited for Charles Chaplin’s Little Tramp. Masina even shuffles forward in bobbing, side-to-side steps like the Tramp, or smiles and looks at the world around her with simultaneous bemusement and confusion, much like Chaplin’s classic character. Years later, Masina was widely known as the “female Chaplin” by critics, while Chaplin himself said, “She’s the actress I admire most.” Watch how Gelsomina interacts with the world. Its marvels enthrall her, yet she remains an outsider to its goings-on. Her large eyes move around, looking, searching, and often find some small miracle of Nature to observe and bring her momentary joy. After she abandons Zampanò at the farm, she sits in a ditch, places a twig on her hand, and watches it blow away in the wind; she does this again, and this time it makes her smile as she looks up into the air where it blew away. Then her smile dissipates into a frown. Her sensory escape is over. The joy Gelsomina derives from such moments despite her punishing existence is a heartrending contrast. But moments like these in La strada emphasize Fellini’s spiritualism, whereas the world, the harsh road, and tragedy of the narrative are his neorealists origins seeping through. As always, Fellini is at once the journalist and the painter, not unlike Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938) or The Great Dictator (1940), which used his particular brand of comic escape to address issues such as Marxism, poverty, and Adolf Hitler.

Or perhaps Masina taps into our cinematic memory to charm us. When Zampanò first gives Gelsomina her costume for their act, he hands her a pile of clothes—an oversized coat and a bowler hat, both best suited for Charles Chaplin’s Little Tramp. Masina even shuffles forward in bobbing, side-to-side steps like the Tramp, or smiles and looks at the world around her with simultaneous bemusement and confusion, much like Chaplin’s classic character. Years later, Masina was widely known as the “female Chaplin” by critics, while Chaplin himself said, “She’s the actress I admire most.” Watch how Gelsomina interacts with the world. Its marvels enthrall her, yet she remains an outsider to its goings-on. Her large eyes move around, looking, searching, and often find some small miracle of Nature to observe and bring her momentary joy. After she abandons Zampanò at the farm, she sits in a ditch, places a twig on her hand, and watches it blow away in the wind; she does this again, and this time it makes her smile as she looks up into the air where it blew away. Then her smile dissipates into a frown. Her sensory escape is over. The joy Gelsomina derives from such moments despite her punishing existence is a heartrending contrast. But moments like these in La strada emphasize Fellini’s spiritualism, whereas the world, the harsh road, and tragedy of the narrative are his neorealists origins seeping through. As always, Fellini is at once the journalist and the painter, not unlike Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938) or The Great Dictator (1940), which used his particular brand of comic escape to address issues such as Marxism, poverty, and Adolf Hitler.

The chapter on La strada in Tullio Kezich’s book Federico Fellini: The Films opens with a quote from Fellini: “This film is a complete catalogue of my entire mythological world, a dangerous representation of my identity that was undertaken with no precedent whatsoever.” From this raw, deeply personal source of inspiration, Fellini delivered a rare and, arguably, unselfconscious work of art unto the world, solidifying forevermore what it meant to be Felliniesque—self-indulgent creation for the sake of expression. With La strada, Fellini disassociates himself from neorealism and expresses himself purely, without a concern for how critics or audiences will interpret it. The filmmaker achieves what he later describes as “peace with myself and my pride as an artist.” Though La strada may be a painful reflection of Fellini’s life, it remains an enigmatic fairy tale whose interpretation is so specific to its author that one cannot help but project meaning onto it. Perhaps this is why the film ensnares our emotions to such a powerful scale; it allows its audience to find its purpose within ourselves, just as Fellini and Masina found their own meanings with the story. That is the enduring power of Fellini’s work, beginning with La strada and lasting for much of his career afterward—the way his pictures were made for himself, yet also have a profound effect on his audience, is a cinematic rarity.

Bibliography:

Albpert, Hollis. Fellini: A Life. New York: Marlowe & Company, 1986.

Aldouby, Hava. Federico Fellini: Painting in Film, Painting on Film. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Bondanella, Peter. The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: His Life and Films. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2002.

Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: The Films. New York: Rizzoli, 1st Edition, 2010.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review