The Definitives

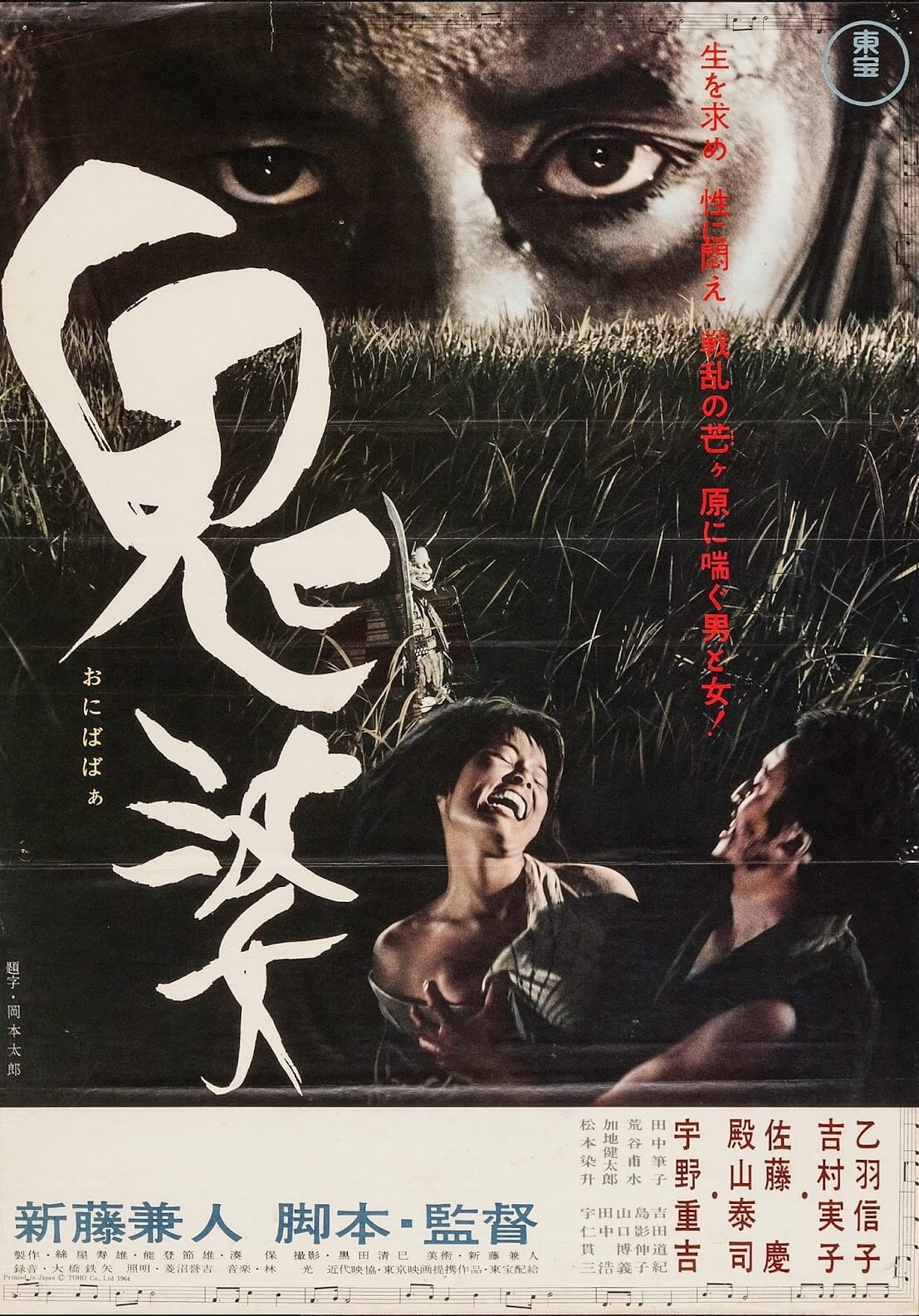

Kwaidan

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Kwaidan, a lavishly designed anthology film by Masaki Kobayashi, opens with ink droplets expanding in water. Individual bursts of black, blue, and crimson calligraphy ink swirl into dazzling, almost psychedelic shapes, suggesting how authors have circulated the same stories over centuries of Japanese history. Passed down in the written and oral tradition, the film’s four tales draw from versions authored by Lafcadio Hearn, and Kobayashi gives them new life. Kwaidan, a title transliterated from kaidan, a Japanese term meaning a strange story told in an old-fashioned style, has been called a horror anthology. However, the ornate and extravagantly designed production does not seek to frighten or shock, as many horror films do. Rather, its length provides a challenge over its three-hour runtime, and its meaning remains intentionally elusive, creating a sense of awe and mystery. It’s a film of methodical pacing, theatricality, and avant-garde flourishes, which work in harmony to acknowledge that something lies beyond any grounded understanding of reality. The production guides the viewer’s attention to the pristine and distinctly Japanese formalism in the cinematic, theatrical, and musical art forms on display. Yet, it also breaks from tradition in evocative ways, punctuating the uncanniness that looms just outside of our everyday perceptions.

Released in 1965, Kwaidan remains an oddity in Kobayashi’s work. Many of his films either occur in the modern era or remark on it. Period pieces such as Harakiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967) may take place in feudal Japan and venture into the sword-fighting genre, but they comment on the state’s contemporary oppression and violence. As a pacifist who aspired to become a filmmaker only to have his dreams delayed when drafted during World War II, Kobayashi resented Japan’s Imperial Army and what it represented. He witnessed the lows of humanity serving in Manchuria, followed by his internment at the US labor camp in Okinawa. By the time the war was over, Kobayashi had to serve a four-year apprenticeship under Keisuke Kinoshita before graduating to a directorship with his debut, Youth of the Sun (1952). It took years of working in the Shochiku house style before he broke away and made something more personal, starting with The Thick-Walled Room (1956), about war criminals held in Japan’s Sugamo Prison. Kobayashi wasn’t ambiguous about his political filmmaking, either; his remarks in interviews support an antiauthoritarian interpretation of his work. The vast majority of his films question how society, especially Imperialist Japan’s militarism, oppresses and dehumanizes.

With Kwaidan, Kobayashi does not comment on the world today, but he suggests that the world still contains some supernatural mystery. In Stephen Prince’s book about Kobayashi—A Dream of Resistance, the only substantial text in English dedicated to the filmmaker—the author notes how Kobayashi grew up in the mountains of Hokkaido, surrounded by “a sense of the sublime evoked by majestic views from on high.” Prince links this perspective to spirituality in the director’s work that inspired not only Kobayashi’s appreciation of the Kantian sublime but a panoramic style that affected how he frames the world from a distance, regarding the drama from an almost objective view that looks upon events with an understanding of their inevitability. Kobayashi does not merely tell a story then; he acknowledges that something spiritually significant unfolds before us, revealing something essential about how the universe operates. His camera’s perspective, often positioned from on high or from a distance—from what Prince describes as a “vertical dimension”—acknowledges that there’s a grander meaning to subjects such as wartime atrocity. However, Kobayashi does not try to evoke a precise religious response with what might be called his “God’s eye view” framing, as he was not a Christian, nor did he subscribe to any form of organized religion. But his frequent use of this “vertical dimension” seems to yearn for a grander meaning to the horrifying things that happen in the world.

With Kwaidan, Kobayashi does not comment on the world today, but he suggests that the world still contains some supernatural mystery. In Stephen Prince’s book about Kobayashi—A Dream of Resistance, the only substantial text in English dedicated to the filmmaker—the author notes how Kobayashi grew up in the mountains of Hokkaido, surrounded by “a sense of the sublime evoked by majestic views from on high.” Prince links this perspective to spirituality in the director’s work that inspired not only Kobayashi’s appreciation of the Kantian sublime but a panoramic style that affected how he frames the world from a distance, regarding the drama from an almost objective view that looks upon events with an understanding of their inevitability. Kobayashi does not merely tell a story then; he acknowledges that something spiritually significant unfolds before us, revealing something essential about how the universe operates. His camera’s perspective, often positioned from on high or from a distance—from what Prince describes as a “vertical dimension”—acknowledges that there’s a grander meaning to subjects such as wartime atrocity. However, Kobayashi does not try to evoke a precise religious response with what might be called his “God’s eye view” framing, as he was not a Christian, nor did he subscribe to any form of organized religion. But his frequent use of this “vertical dimension” seems to yearn for a grander meaning to the horrifying things that happen in the world.

Kobayashi’s perspective is never more apparent in his work than in Kwaidan, which he made in honor of Yaichi Aizu, a mentor who introduced him to Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), the world-traveling writer who penned ghost stories in his chosen home of Japan. Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things from 1904, along with his other published texts, provided the source material for Kobayashi’s film. Hearn was born in Greece but made homes in Ireland, the United States, and Martinique, writing about Creole cultures, French literature, and Black cultures in America and the West Indies. Finally, he spent the last fourteen years of his life in Japan. There, Hearn became immersed in Japanese culture and history. He converted to Buddhism, married a Japanese woman, and they had four children. He set out to explore Japan’s rich history of folk stories. Since he could not read Japanese, Hearn’s wife told him the stories, and he authored several collections based on his adaptations. His books introduced the Western world to a culture still considered unusual and mysterious; they also reinvigorated Japanese interest in kaidan. Aizu read Hearn’s texts and taught them to his students, among them Kobayashi.

Kwaidan began production in 1964 from a screenplay by Yoko Mizuki, an experienced writer who had often worked with director Mikio Naruse. It would be Kobayashi’s first color film—amazingly so, given the luminous result—and he sought absolute control over the color and compositions. He could not achieve such control with location shooting, so he moved the production entirely to soundstages (in a move that recalls Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s desire for formal control over every detail while making 1947’s Black Narcissus). Kobayashi and his crew scouted a former airplane hangar, which gave the director the freedom to create enormous sets but at a high cost. The sheer size of the space required time-consuming decoration work between the shooting of each story, and lighting the massive hanger required numerous generators. Each story featured a unique cyclorama painted by hand and sprawling set-pieces. Cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima captured the elaborate artistry in the panoramic TohoScope, whose wide frame wraps at much the same curvature as the cycloramas. The production took nearly a year to complete, given the extensive demands. Toho promised 90 million yen to the production during that time, although the payouts came in delayed installments. By the time Kobayashi began work on the third segment, he had spent the allotted budget. The director sought personal loans from friends and sold his house to complete the film. The expense left Ninjin Club, his production company, bankrupt. All of this led to Kwaidan becoming the most expensive Japanese film ever made at the time.

Moreover, it was an artistic risk. There has never been a film quite like Kwaidan before or since, even though its logline is that of a horror anthology. Even though anthologies ranging from the comic-booky Creepshow (1982) to the grainy home video stylings of the V/H/S series prove common enough among today’s genre output, they were uncommon in the early 1960s. Today, most examples resemble each other to a fault. They usually feature multiple directors or authors that, when combined, result in an uneven structure due to inconsistent storytelling. One story or episode may work well, the next may fail miserably, and the wraparound story rarely does much to bring them all together. But Kobayashi’s treatment in Kwaidan represents a uniformity of style and content. Each tale features a pace and staginess that reminds us how much this era’s Japanese cinema draws from theatrical traditions. Each finds Kobayashi’s characters discovering that they inhabit a world far different from what they assumed. In its folkloric roots and aversion to otherwise obligatory lessons, the film recalls Alvin Schwartz’s book series Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, in that most do not have a stated moral to their story. They seek only to add a supernatural dimension to our understanding of the universe. These qualities leave Kwaidan to feel like an oddity—or perhaps shining example—among anthologies, questioning not only the fabric of reality but traditional filmmaking.

Moreover, it was an artistic risk. There has never been a film quite like Kwaidan before or since, even though its logline is that of a horror anthology. Even though anthologies ranging from the comic-booky Creepshow (1982) to the grainy home video stylings of the V/H/S series prove common enough among today’s genre output, they were uncommon in the early 1960s. Today, most examples resemble each other to a fault. They usually feature multiple directors or authors that, when combined, result in an uneven structure due to inconsistent storytelling. One story or episode may work well, the next may fail miserably, and the wraparound story rarely does much to bring them all together. But Kobayashi’s treatment in Kwaidan represents a uniformity of style and content. Each tale features a pace and staginess that reminds us how much this era’s Japanese cinema draws from theatrical traditions. Each finds Kobayashi’s characters discovering that they inhabit a world far different from what they assumed. In its folkloric roots and aversion to otherwise obligatory lessons, the film recalls Alvin Schwartz’s book series Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, in that most do not have a stated moral to their story. They seek only to add a supernatural dimension to our understanding of the universe. These qualities leave Kwaidan to feel like an oddity—or perhaps shining example—among anthologies, questioning not only the fabric of reality but traditional filmmaking.

An unidentified omniscient narrator passes along each story. The initial episode entitled “The Black Hair” came from Hearn’s “The Reconciliation,” published in his book Shadowings in 1900. The tale recalls Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), about a potter who leaves his wife behind during wartime to sell his wares; when he returns, she has since died, and he spends a night with her ghost. Similarly, “The Black Hair” follows a destitute samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) who, resenting their poverty, abandons his wife (Michiyo Aratama) to serve in a distant province. There, he marries an indifferent second wife (Misako Watanabe). Before long, he realizes that he “did not understand the value of love,” according to the narrator. It’s not until several years later that he works up the courage to leave his powerful and uncaring second wife for his first. When he finally returns home, the samurai finds that his first wife has barely aged. He begs her forgiveness, which she grants, but he soon realizes that he has been interacting with a corpse. The samurai’s face goes white and, as he scrambles to escape the scene, he grows whiter and older with each cut by editor Hisashi Sagara. Out of place sounds, such as cracks and a yawning banshee cry, ring in our ears like a warning. Finally, his wife’s possessed black hair, all that remains of her former self, comes alive and wraps around him. The narrator does not attempt to draw out a lesson from these events. It is, to quote the anthology-adjacent Magnolia (1999), “something that happens.”

Next, “The Woman of the Snow,” drawn from Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, follows Minokichi (Tatsuya Nakadai), a woodcutter caught in a forest during a blizzard. Almost immediately, an otherworldly presence overtakes the scene. The camera looks down at trees moving in the wind, like something alive. The cyclorama backdrop features wispy clouds that resemble eyes. A sound like whale song comes from the woods, though perhaps these are non-diegetic sounds. Minokichi and his friend take refuge in a boatman’s shack, where an ice-blue-skinned spirit woman (Keiko Kishi) visits them. She freezes the friend but takes pity on Minokichi—on the condition that he never speaks of their encounter. A year later, while walking home through a forest at sunset, Minokichi meets a young woman. They fall in love and have several children. The story resolves itself in a manner that anticipated an episode from another horror anthology, Tales from the Darkside (1990), about a living gargoyle that doubles as a beautiful woman. Eventually, Minokichi recounts the story of “the woman of the snow who comes looking for blood” to his wife, who, of course, is the so-called Snow Maiden. But rather than freeze her husband as she did the friend all those years ago, she must abandon her family. When she does, the film finds Minokichi alone, and a stagelike spotlight shines on his tragic solitude.

After an intermission comes the third, most extended, and most engrossing entry in the film, called “Hoichi the Earless,” which also appeared in Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Thing. Twice as long as the others, the story’s first part entails a song recounting The Tale of the Heike, about a twelfth-century naval battle, presented as an epically rendered story-within-a-story. The massive numbers of dead from this battle now haunt a beach. At a nearby temple, Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura)—a biwa hoshi, or blind musician who, as a servant, performs stories with strums of their biwa for the ruling class—makes his home. Night after night, the temple’s monks notice Hoichi’s absence from the temple. They follow him and discover he has been performing The Tale of the Heike for the ghosts of the naval battle—alternatively shown as eerie figures shrouded in fog or floating fireballs—and Hoichi was unaware that he’s been performing for phantoms. To free Hoichi from his arrangement with the spirits, the monks cast a protective spell by covering his body with characters that make him invisible to spirits. The monks tell him that, when the spirits visit that night, Hoichi must say nothing. Unfortunately, the monks forget to cover Hoichi’s ears with the protective characters. When a samurai ghost comes to gather Hoichi for that evening’s performance, he sees nothing but ears floating and resolves to take them back to his masters as proof that Hoichi was not there in his entirety. The young biwa player is left mutilated, his ears ripped from his head. However, the narrator assures us that the incident led to Hoichi’s story spreading across the land, giving him fame and fortune.

After an intermission comes the third, most extended, and most engrossing entry in the film, called “Hoichi the Earless,” which also appeared in Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Thing. Twice as long as the others, the story’s first part entails a song recounting The Tale of the Heike, about a twelfth-century naval battle, presented as an epically rendered story-within-a-story. The massive numbers of dead from this battle now haunt a beach. At a nearby temple, Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura)—a biwa hoshi, or blind musician who, as a servant, performs stories with strums of their biwa for the ruling class—makes his home. Night after night, the temple’s monks notice Hoichi’s absence from the temple. They follow him and discover he has been performing The Tale of the Heike for the ghosts of the naval battle—alternatively shown as eerie figures shrouded in fog or floating fireballs—and Hoichi was unaware that he’s been performing for phantoms. To free Hoichi from his arrangement with the spirits, the monks cast a protective spell by covering his body with characters that make him invisible to spirits. The monks tell him that, when the spirits visit that night, Hoichi must say nothing. Unfortunately, the monks forget to cover Hoichi’s ears with the protective characters. When a samurai ghost comes to gather Hoichi for that evening’s performance, he sees nothing but ears floating and resolves to take them back to his masters as proof that Hoichi was not there in his entirety. The young biwa player is left mutilated, his ears ripped from his head. However, the narrator assures us that the incident led to Hoichi’s story spreading across the land, giving him fame and fortune.

In his essay about the film, Geoffrey O’Brien notes how the first three stories contain vows that, when broken, have supernatural consequences, revealing that “supernatural terror” awaits beyond the limits of our world. If this doubtful moral lining exists in the other stories, it does not appear in the final tale, “In a Cup of Tea.” The story comes from Hearn’s 1902 collection Kotto: Being Japanese Curios with Sundry Cobwebs, and the film’s narrator claims it was incomplete. It begins when a respected samurai, Sekinai (Kan’emon Nakamura), goes for water and sees another man’s face reflected, smiling at him almost mockingly. One night, the man appears to Sekinai inside his master’s compound. Sekinai raises the alarm and attacks, but the man disappears into thin air, and no one will believe Sekinai’s claim. The story ends abruptly when three more spirits visit Sekinai at his home and disappear after a duel. The final flourish to the film finds a publisher (Ganjirô Nakamura) looking for the author (Osamu Takizawa) of “In a Cup of Tea.” The author has disappeared in the middle of writing the story. While searching the home with the author’s wife, the publisher reads the story and the author’s notes: “I could imagine several possible endings, but none of them would leave you satisfied.” But Kwaidan has its own chilling conclusion: the publisher and wife find the author trapped inside a jar of water, as though the very concept of his short story consumed him, much as Kobayashi’s film has consumed us.

Each of the four stories boasts unparalleled artistry, which results in a familiar yet strange quality when combined with its classical motifs and avant-garde touches. It came after a marked shift in Kobayashi’s career and style, prompted by a new collaboration with composer Toru Takemitsu on The Inheritance (1962)—their first of ten films together. Before his work with Takemitsu, Kobayashi used traditional music to score his films. His earlier scores accompanied his films’ action and accented emotion, as typical scores usually do. According to Kobayashi, Takemitsu’s approach contrasts traditionalism and “uses the music to slash the monotony,” creating a multimodal approach to sound (both diegetic and non-diegetic), images, and music. In “The Black Hair,” when the husband returns home and discovers his first wife has become a ghost, he frantically races from the dilapidated home. Shot in slow-motion, the sequence features the husband stumbling, knocking over furniture, and falling. But Takemitsu drops all diegetic sound. There is no music, only the sound of wood fracturing and tearing—and it’s like something from another world scratching its way into our realm. When his first wife’s possessed hair finally attacks him, diegetic sound returns, along with his screams. The overall effect disorients the viewer, leaving us deaf and unsure of what will come next.

Takemitsu’s minimalism and experimental style drew from Western aural movements, resisting Japanese tradition out of defiance of the state. Inspired by John Cage’s indeterminate music, which diverges from typical musical structures bound by tempo, harmony, and composition, Takemitsu relied on an evocative open form using primarily traditional Japanese instruments. Besides his many collaborations with Kobayashi, the composer also worked with Akira Kurosawa, Shohei Imamura, Kon Ichikawa, Nagisa Oshima, Hiroshi Teshigahara, and Masahiro Shinoda—practically every great Japanese filmmaker of the era. For Kwaidan, he used traditional Japanese instruments and cultural sounds in a style that contrasted their typical application in Japanese military music. He wielded the traditional to create a subversively modern sound that transports the viewer into the film’s bizarre world. In doing so, he forges an uneasy relationship between silence and sound, dropping the audio in pronounced moments that emphasize the presence of something supernatural. In “The Woman of the Snow,” for instance, the sound of Minokichi’s long slog through blizzard snow should be pounding us with the sound of the ear-shattering wind. Instead, the slowness of the scene and Takamitsu’s piercing flutes—coupled with the eyelike clouds painted on the cyclorama—signify a spiritual presence in the woods.

Takemitsu’s minimalism and experimental style drew from Western aural movements, resisting Japanese tradition out of defiance of the state. Inspired by John Cage’s indeterminate music, which diverges from typical musical structures bound by tempo, harmony, and composition, Takemitsu relied on an evocative open form using primarily traditional Japanese instruments. Besides his many collaborations with Kobayashi, the composer also worked with Akira Kurosawa, Shohei Imamura, Kon Ichikawa, Nagisa Oshima, Hiroshi Teshigahara, and Masahiro Shinoda—practically every great Japanese filmmaker of the era. For Kwaidan, he used traditional Japanese instruments and cultural sounds in a style that contrasted their typical application in Japanese military music. He wielded the traditional to create a subversively modern sound that transports the viewer into the film’s bizarre world. In doing so, he forges an uneasy relationship between silence and sound, dropping the audio in pronounced moments that emphasize the presence of something supernatural. In “The Woman of the Snow,” for instance, the sound of Minokichi’s long slog through blizzard snow should be pounding us with the sound of the ear-shattering wind. Instead, the slowness of the scene and Takamitsu’s piercing flutes—coupled with the eyelike clouds painted on the cyclorama—signify a spiritual presence in the woods.

The new approach to music prompted Kobayashi to reconsider his aesthetic choices, leading him to craft a majestic yet severe purpose with each camera movement, splash of color, performative gesture, and piece of set decoration. His previous film, and arguably his finest, Harakiri, pushed his early career drive toward realism into comparative hyperstylization. Composed of a rigid discipline, Kobayashi’s films would become increasingly refined in part because of Takemitsu’s influence. Over their ten collaborations, the director and composer continued to cultivate their approach; however, their work on Kwaidan reaches an uncompromising zenith. Here, Kobayashi adopts a myriad of storytelling styles, from the compositional bird’s-eye-view perspective of emakimono scrolls, to the biwa-hoshi mode of performance, and to a touch of traditional Japanese theater. Shots of the immersive sets look like an enormous stage, intentionally so, to convey the theatricality of reality. If our world is merely a stage, then behind, below, and above it reside the spirits beyond what we can see. Kobayashi frees Kwaidan of conventional cinema’s naturalism, thus making the film into a reflector of unnatural states of being inside mannered and ornamented art forms. He embraces surfaces and resists commenting on their meaning to achieve this, even as he showcases their uncanniness. His approach accentuates, as Prince notes, “pattern and decorative effect instead of sustained psychological focus through time.” In almost any other film, the lack of substance behind the narratives might degrade our experience. Here, it brings us closer to accepting that the world beyond is always present. We just can’t always see it.

Kobayashi’s stylized treatment of these traditional stories underscores how, unlike folklore that originated in European countries, Japanese kaidan folklore does not impart strict moralized points of view or even implant an ambiguous lesson that demands interpretation to understand. He sets out to evoke a feeling that the world’s limitations extend outside of our visual input. Noriko Reider, a scholar of such folklore, observes, “Unlike supernatural tales of previous ages, one sees very few moral examples in these stories. The appeal fundamentally lies in how strange things can be.” Something uncanny and spiritual exists outside of the everyday, and kaidan stories typically seek to share accounts that reinforce the existence of these otherworldly forces in the reader or viewer. Moreover, Kobayashi uses the stories to explore the limits of formal austerity and experimentation, testing the medium just as his characters experience the boundaries of reality as they know it. Prince writes that Kwaidan explores “aesthetic modes of expression in ways that connect with Japan’s traditional arts and point away from the material world and toward metaphysical dimensions of experience.” In both style and narrative, then, the film embraces the strange and unusual.

Kobayashi’s stylistic risks and personal toiling paid off, artistically speaking. When he and Takemitsu took Kwaidan to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965, the jury awarded the film the Special Jury Prize. However, the film screened in an abbreviated version that omitted “The Woman of the Snow” and featured trimmed versions of the other stories. Many prints that circulated internationally ran in the edited version of 125 minutes, and not until many years later was Kobayashi’s full 182-minute version restored and distributed around the globe. Although the film earned award recognition, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, its commercial performance was another story. Its perceived failure resulted in the director’s career suffering. Kwaidan was the end of a three-picture deal between Kobayashi and Toho, and the head of Shochiko, Kido Shiro, fired Kobayashi for his reckless spending. At the time, studios like Shochiko and Toho were firing spendthrift directors to avoid undue financial risk in the volatile marketplace that had television to compete with—regardless of a filmmaker’s reputation or past successes. In the years to follow, Kobayashi struggled to find work, despite having made some of Japan’s most successful and renowned films. For the remainder of his career, he would work as a free agent, setting up independent projects without the studio backing he had grown accustomed to. Even so, he had no regrets about making Kwaidan; he had made an elegiac work of art.

Kobayashi’s stylistic risks and personal toiling paid off, artistically speaking. When he and Takemitsu took Kwaidan to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965, the jury awarded the film the Special Jury Prize. However, the film screened in an abbreviated version that omitted “The Woman of the Snow” and featured trimmed versions of the other stories. Many prints that circulated internationally ran in the edited version of 125 minutes, and not until many years later was Kobayashi’s full 182-minute version restored and distributed around the globe. Although the film earned award recognition, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, its commercial performance was another story. Its perceived failure resulted in the director’s career suffering. Kwaidan was the end of a three-picture deal between Kobayashi and Toho, and the head of Shochiko, Kido Shiro, fired Kobayashi for his reckless spending. At the time, studios like Shochiko and Toho were firing spendthrift directors to avoid undue financial risk in the volatile marketplace that had television to compete with—regardless of a filmmaker’s reputation or past successes. In the years to follow, Kobayashi struggled to find work, despite having made some of Japan’s most successful and renowned films. For the remainder of his career, he would work as a free agent, setting up independent projects without the studio backing he had grown accustomed to. Even so, he had no regrets about making Kwaidan; he had made an elegiac work of art.

The film remains so powerful even today through Kobayashi’s use of overt artifice to conjure ethereal emotional responses, which function differently than conventional horror or escapist ghost stories. Kwaidan does not cause the viewer to jump in their seat or grip their partner for safety. Instead, the director immerses his audience in sensory pleasures and the meticulousness of his craft, deprioritizing the political assertions that made films like Harakiri or his trilogy, The Human Condition (1959, 1961), so potent. What Kwaidan does so well is present a world whose limits remain unknown, where things happen that we cannot explain. Its length and intentional pacing immerse the viewer in an open headspace, where ghosts and angry spirits dwell in stories of vengeance, loneliness, uncertainty, and despair. Above all, Kobayashi continues the tradition of folkloric storytelling through the twentieth century’s most remarkable mode of communication, using methods of expression that integrate formal influence from theater and avant-garde music. The film’s lasting effect has less to do with its narratives than the unusual, beautiful, and unforgettable cinematic language Kobayashi creates in their service.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your suggestion and continued support, Dave!)

Bibliography:

O’Brien, Geoffrey. “Kwaidan: No Way Out.” Criterion.com, 21 October 2015. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3756-kwaidan-no-way-out. Accessed 1 October 2021.

Prince, Stephen. A Dream of Resistance: The Cinema of Kobayashi Masaki. Rutgers University Press, 2017.

Reider, Noriko T. “The Appeal of ‘Kaidan,’ Tales of the Strange.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 59, no. 2, Nanzan University, 2000, pp. 265–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178918. Accessed 1 October 2021.

— “The Emergence of ‘Kaidan-Shū’ The Collection of Tales of the Strange and Mysterious in the Edo Period.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 60, no. 1, 2001, pp. 79–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178699. Accessed 1 October 2021.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review