The Definitives

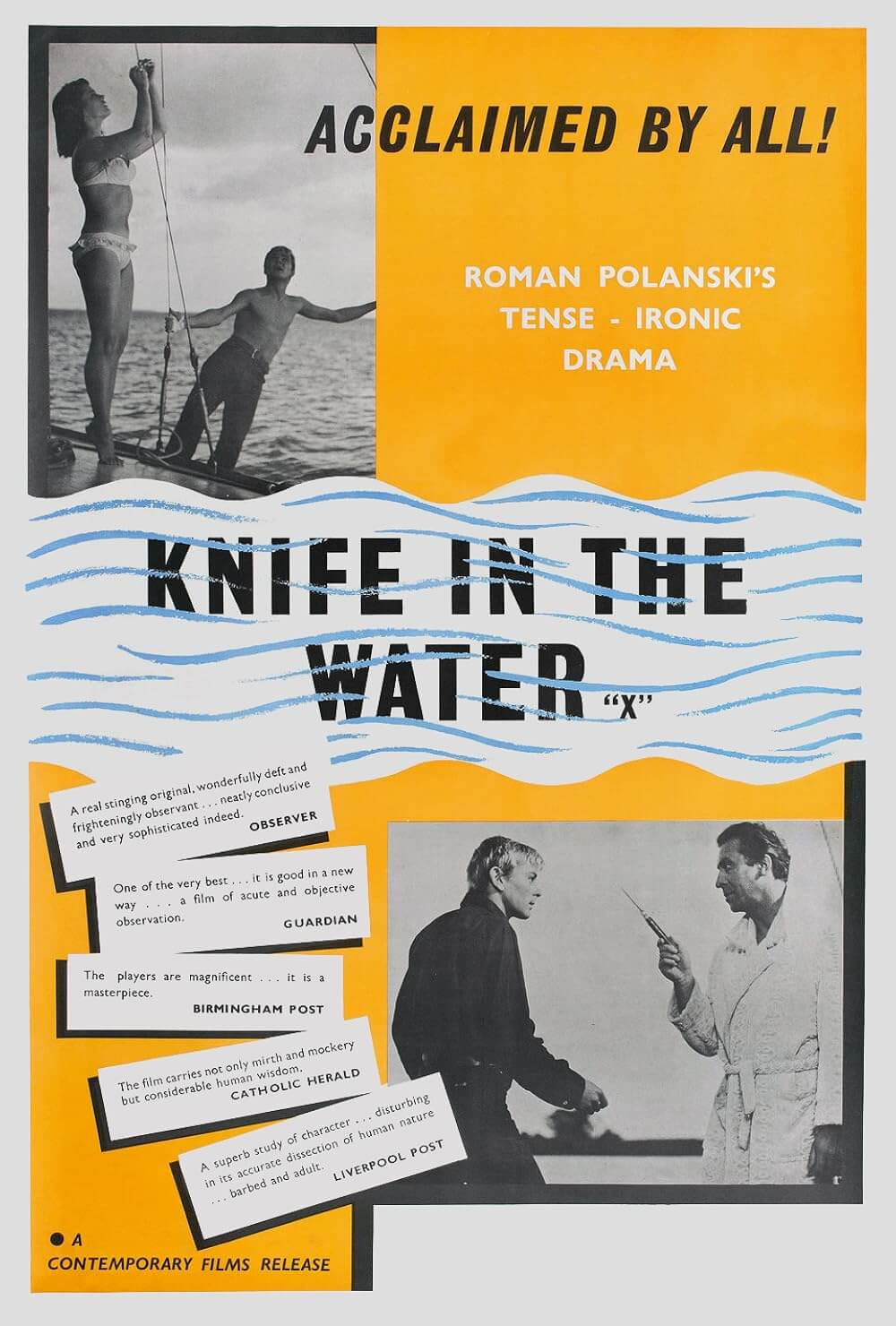

Knife in the Water (1962)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In 1962, when stopped at the German border to leave his home country of Poland, where he would not return for nearly twenty years, Roman Polanski had hardly any possessions with which to impress customs officials. This boyish 28-year-old man drove a ramshackle Mercedes convertible filled with books and clothes and records. His black poodle Jules sat in the car as the officers inspected the lot. Among the articles tossed into the vehicle, the officials noted film cans containing Knife in the Water, Polanski’s first feature-length motion picture. When they stamped his passport, allowing him to study and work abroad, Polanski gestured back at Poland, which had rejected him as a fledgling filmmaker, and remarked, “Someday they’ll remember me.” Nearly fifty years later, with the director’s career torn between a series of landmark films and infamous headlines, to be sure, they remember Roman Polanski. Although today, his films, notably his earlier work like Knife in the Water and Repulsion, are tragically eclipsed by the director’s public persona. This is Polanski’s greatest curse: that his turbulent, at times tragic life overtakes the due attention to his cinema. His films in particular are subject to biographical readings, sometimes unjustly, because, as the director remains resistant to interviews, scholars have only his films to cling to for psychological extrapolation. And why not? Surely his eventful personal life has some bearing on his subsistence as a filmmaker; the two aspects are inexorably connected, though how much depends on the interpretation.

Rather than allowing Polanski’s publicized exploits and personal misfortunes to overshadow his work, consider that, like any auteur, the director and his films share an undeniable correlation on and offscreen. One does not completely inform the other, yet their relationship, given the intensity of the events in Polanski’s life and their reflectivity of his cinema, cannot be ignored. As much as any artist places themselves into their work, Polanski is drawn to particular kinds of stories, whether from his own imagination or a piece for adaptation. They involve claustrophobia, sexuality, voyeurism, solitude, and paranoia. There are undeniable links between the stories he puts on film and key incidents in his life. And while his films certainly do not read like an autobiographical cipher to Polanski himself, to ignore the links between director and film in this case would be willful ignorance on the part of even the most casual viewer.

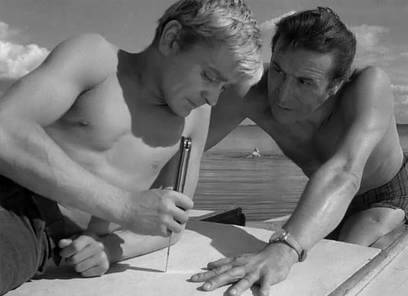

Knife in the Water tells a story of limited spaces and intense circumstances. The thriller involves a married couple who take a young drifter with them on their yacht for a brief retreat. Secluded on a boat in Poland’s Masurian Lake District, with conditions ranging from aggressive storms to dead calm, there is nowhere to escape, and changes in weather signal changes in mood. The characters are entirely isolated; not even random extras appear in the background. Polanski sought to make a simple film about opposing characters forced to confront one another, about establishment battling anti-establishment in an intimate, airtight setting. His personality inhabits every aspect, from investigations of claustrophobia and divergent personalities to clever framing on a cramped boat set. And through his artistry and skill, Polanski overcomes an impossible shooting location and the outward minimalism of the story to construct a tale defined by the profound relationship between its suffocating backdrop and psychological potency.

Knife in the Water tells a story of limited spaces and intense circumstances. The thriller involves a married couple who take a young drifter with them on their yacht for a brief retreat. Secluded on a boat in Poland’s Masurian Lake District, with conditions ranging from aggressive storms to dead calm, there is nowhere to escape, and changes in weather signal changes in mood. The characters are entirely isolated; not even random extras appear in the background. Polanski sought to make a simple film about opposing characters forced to confront one another, about establishment battling anti-establishment in an intimate, airtight setting. His personality inhabits every aspect, from investigations of claustrophobia and divergent personalities to clever framing on a cramped boat set. And through his artistry and skill, Polanski overcomes an impossible shooting location and the outward minimalism of the story to construct a tale defined by the profound relationship between its suffocating backdrop and psychological potency.

His life characterized by continuous, upsetting hardships, the young Polanski learned to endure early on. Having lost his mother to the atrocities of Auschwitz, as a boy he barely lived through World War II, surviving the Nazi “cleansing” by his wits and unbelievable luck. Separated from his family, he took shelter wherever he could, eating maggot-ridden food and living on the move. The Holocaust became the event which defined his existence from there on out, as Polanski would subsist as an exile of sorts, an orphan who just barely scraped by, embraced every moment of life, and existed in this moment. Social convention did not apply while scavenging the streets of Krakow for food or dodging Nazi patrols. His hero during his later college years would become Bertrand Russell, whose ‘live life for the moment’ thesis appealed to this non-practicing, persecuted Polish Jew. (Indeed. Russell once wrote, “One should as a rule respect public opinion in so far as is necessary to avoid starvation and to keep out of prison, but anything that goes beyond this is voluntary submission to an unnecessary tyranny, and is likely to interfere with happiness in all kinds of ways.” Polanski’s ever-rascally ways later in life seem to closely follow this edict.) And so, he conspicuously avoided addressing the Holocaust in his films, until 2002’s triumphant The Pianist, for which he won the Oscar for Best Direction.

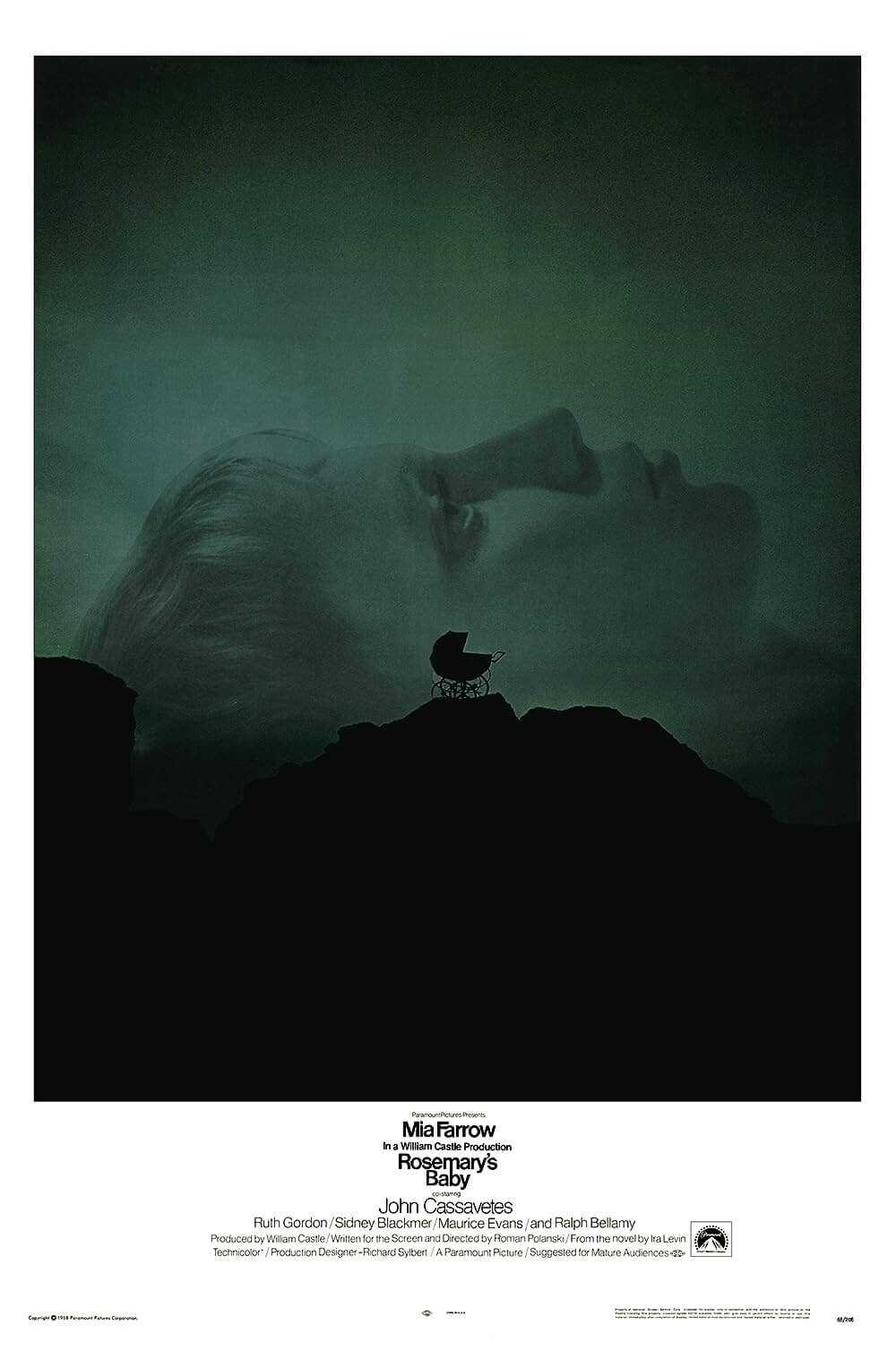

If enduring the Holocaust was not enough, in 1949, Polanski barely avoided becoming the victim of black marketer and murderer Janusz Dziuba, who had killed eight others in Krakow in muggings staged to look like trades. Left bludgeoned and drenched in blood, Polanski just survived. Though Dziuba was caught, the event would give Polanski nightmares about showers of blood for years to come, an image which he reproduced in 1966 for Cul-de-sac. This would not be his last connection to a murder. Forced to abandon his home country when then-contemporary Polish critics rejected Knife in the Water, after the film’s international release and subsequent honors, he landed in Hollywood. Polanski’s popularity in the United States was solidified with pictures like Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby by 1969, the year when the Manson “family” slaughtered his eight-month pregnant wife Sharon Tate. When he was later charged with statutory rape for having sex with a 13-year-old girl, he fled again, finding impermanent reprieve in France.

Not merely about fleeing or escape, Polanski’s life and career, and certainly the thematic undercurrents of the majority of his films, settle on elements of non-conformity and isolation, of existing in one’s own bubble—Knife in the Water most of all. Polanski’s characters survive on the margins, free from or at least hesitant toward orthodoxy, whether compartmentalized by choice or force. No doubt his past and continuance of life lessons regarding the importance of secluded independence have inspired his filmmaking. These concepts are crucial to both his life as an artist and as a human being. For Polanski, conformity is just as dangerous an idea as imprisonment. His aversion to it remains ingrained into his being and vital to his survival. During his rape case, a court-ordered probation report observed, “It is believed that incalculable emotional damage could result from incarcerating the defendant, whose very existence has been a seeming unending series of punishments.”

Not merely about fleeing or escape, Polanski’s life and career, and certainly the thematic undercurrents of the majority of his films, settle on elements of non-conformity and isolation, of existing in one’s own bubble—Knife in the Water most of all. Polanski’s characters survive on the margins, free from or at least hesitant toward orthodoxy, whether compartmentalized by choice or force. No doubt his past and continuance of life lessons regarding the importance of secluded independence have inspired his filmmaking. These concepts are crucial to both his life as an artist and as a human being. For Polanski, conformity is just as dangerous an idea as imprisonment. His aversion to it remains ingrained into his being and vital to his survival. During his rape case, a court-ordered probation report observed, “It is believed that incalculable emotional damage could result from incarcerating the defendant, whose very existence has been a seeming unending series of punishments.”

When Polanski first attended the painstaking five-year program at the National Film School in Lodz, Poland, where every aspect of the filmmaking process was covered in rigorous detail, the young director found himself surrounded by entrenched ideals about what cinema should say and how it should be said. The filmmaking ideal in Poland at the time was the work of Andrzej Wajda, whose films A Generation and Ashes and Diamonds solidified the country’s present preoccupation with embracing their recent history. It was fundamental for the country’s ministry of culture that films should have a direct connection to the social identity of Poland’s recent past. But Polanski refused to dwell on the past. His short films at Lodz—such as the eerie voyeur’s tale The Smile or the surrealist Two Men and a Wardrobe—were oftentimes fantastic, darkly comic efforts dedicated to the themes of relationships, escape, claustrophobia, violence, and sometimes brutal irony, but rarely the past.

Each of Polanski’s short films dealt with human interactions on intimate, often one-on-one terms, so it made sense that his first feature-length film would contain only three characters. Polanski and co-writers Jerzy Skolimowski and Kuba Goldberg worked on the script for Knife in the Water for three weeks non-stop before submitting a draft to the ministry of culture. Skolimowski, another graduate of the Lodz Film School, encouraged Polanski to reduce the period of the story to a tight 24-hour expanse, helping to exaggerate the intensity of the emotions and heighten the tensions from scene to scene. The same story drawn out over a number of days would be melodramatic, but limit the characters to a few hours together, and suddenly the story becomes a venture whose embellishment serves a specific purpose worthy of the audience’s deliberation. Polanski later told The New York Times in a 1971 interview for his bloody interpretation of Macbeth, “What I like is a realistic situation where things don’t quite fit in.” Very little ever feels right in a Roman Polanski film.

Deemed of “thematic concern” and “questionable moral value” by the ministry of culture, Polanski was given a year to complete recommended changes, after which he could resubmit the script for approval to produce. Among the changes needed were general toning down of the sexuality—the physical relationship between the husband and wife characters, and the lack of clothing, despite the story’s necessity for bathing suits, given the location. Additionally, the ministry wanted an overall social value, some lesson the audience could walk away with. Polanski submitted a revised script in 1961 with a few “socially committed” lines that he would later refer to as “bullshit” demanded by the ministry. In the face of these changes, Polanski’s finished film would still play like a scornful blow to Polish cinema of the era, as any required social content recedes when placed next to the crackling elements of his psychological thriller.

Deemed of “thematic concern” and “questionable moral value” by the ministry of culture, Polanski was given a year to complete recommended changes, after which he could resubmit the script for approval to produce. Among the changes needed were general toning down of the sexuality—the physical relationship between the husband and wife characters, and the lack of clothing, despite the story’s necessity for bathing suits, given the location. Additionally, the ministry wanted an overall social value, some lesson the audience could walk away with. Polanski submitted a revised script in 1961 with a few “socially committed” lines that he would later refer to as “bullshit” demanded by the ministry. In the face of these changes, Polanski’s finished film would still play like a scornful blow to Polish cinema of the era, as any required social content recedes when placed next to the crackling elements of his psychological thriller.

To achieve an interaction of opposing character types within a confined space, Polanski establishes his three distinct players early on. He begins Knife in the Water with an upper-middle-class married couple driving to their yacht docked on a lake deep in the countryside. The wife, Krystyna (Jolanta Umecka), drives and annoys her husband, the terribly bourgeois Andrzej (Leon Niemczyk), with what he believes are her deficient skills behind the wheel. Fed up with his complaining, she stops the car and permits him to drive. Up ahead, Andrzej sees a young drifter (Zygmunt Malanowicz). Nearly hitting the young man, he slams on the breaks and censures the vagrant for standing in the middle of the road. Later, seemingly for the sole purpose of demonstrating the superiority of his experience to both his wife and the tramp, Andrzej invites the young man along on their yacht as a deckhand, for the experience. Between the conventional, moneyed, tradition-driven husband, the young rebellious drifter on the outskirts of society, and their mutual object of desire, the demure and discontented wife, Polanski’s scenario proceeds on the constrained chamber of the boat. Add to this environment the drifter’s immense pocket knife, an unabashed phallic symbol, and Polanski’s arrangement becomes a suspenseful, dangerous situation not only of male posturing, but of colliding social ranks. Andrzej and the unnamed drifter compete for the attention of Krystyna, who seems uninterested in both men. In one scene, the drifter climbs up the yacht’s mast, another phallic symbol, to display his physical prowess. During another scene, he demonstrates his talent with the knife with a game of five-finger fillet; later the husband meekly tries to replicate the game when he thinks no one is looking.

And yet, the husband still boasts his stubborn authority to best his younger competition. “If two men are on board, one is the skipper.” Andrzej explains away his cruel pomposity toward the young man to his wife; soon after, he proves his point in a physical altercation that sends the hitchhiker over the side, presumably dead. Immediately regretting his actions and upset at his wife’s condemnations of murder, Andrzej swims in search for the drifter’s body, and then heads for shore. Meanwhile, Krystyna changes her clothes onboard, only to be interrupted by the drifter, who cleverly survived on a buoy. Out of spite for her husband and sheer desire, she sleeps with the younger man, and then sends him on his way skipping over floating logs to safety. By the end, the husband and wife are stripped to their bone without a single safeguard to protect them, their rouses and games exposed. The drifter takes off on his own, to continue his survival by meandering through life, whereas the husband and wife find themselves at a literal and figurative crossroad. Krystyna explains that after Andrzej swam away, the drifter returned and they had intercourse. But the husband refuses to believe his wife’s confession. And so, either he accepts that he has murdered a man and turns himself in to the police, or he can accept his wife’s admission of adultery. Either way, he loses, all because he clings to his own sense of establishment and authority. The only winner in the film is the drifter, who survives without consequence. Knife in the Water thus proves to be about the survival instincts of the non-conformist youth and the ultimate downfall of those unwilling to budge in their time-honored but archaic ways—traditions that were supported by earlier Polish filmmakers such as Wajda, which Polanski did everything in his artistic faculty to detract from.

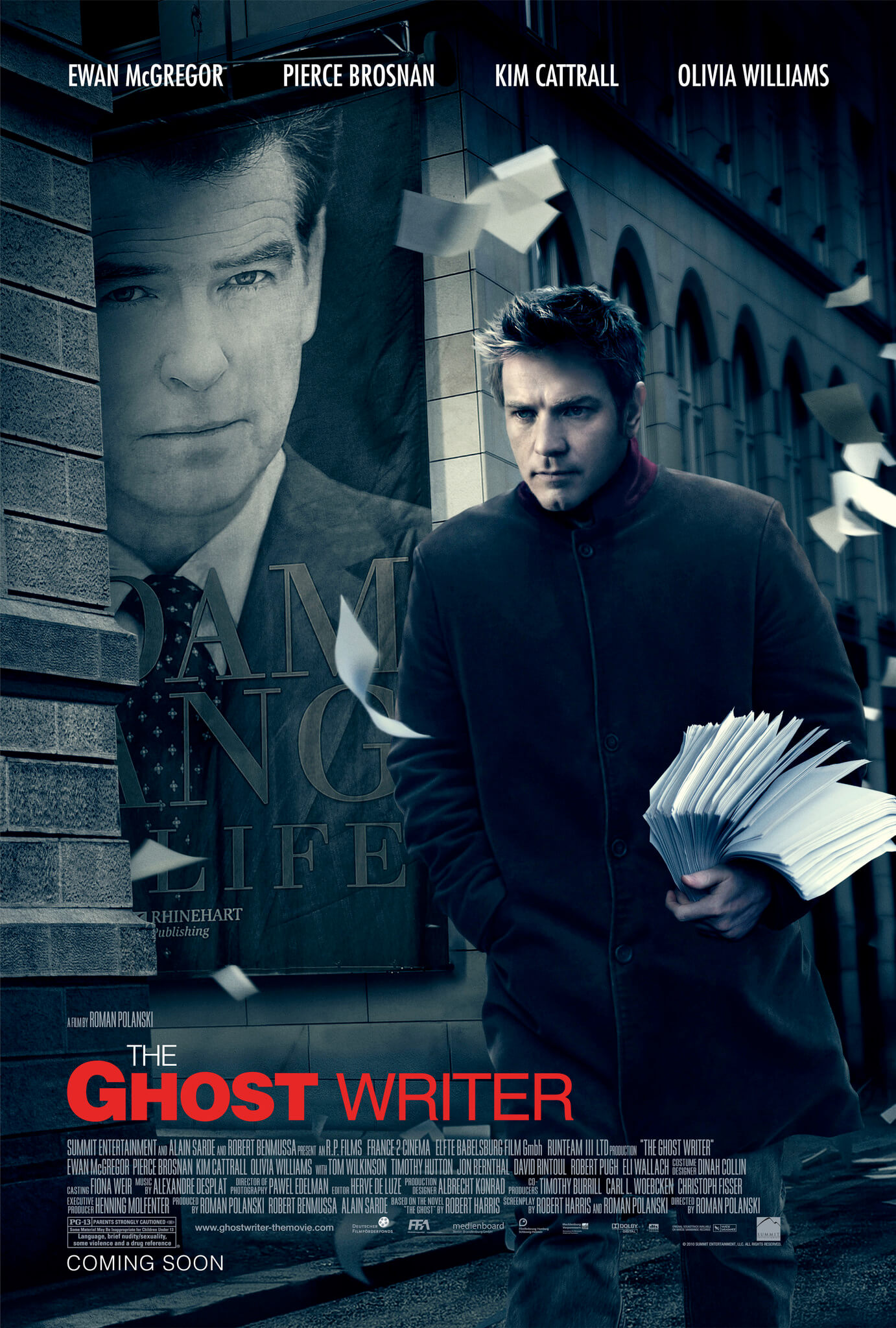

On a more basic level, the film is simply a superb thriller. Every Polanski film can be considered a display of cat-and-mouse relations where the mood shifts from playful to severe with merely a glance or carefully chosen line of dialogue. How profound that the director established this theme with his first film and then continued it throughout his entire career. He makes such stories all the more thrilling by limiting the number of characters and enclosing them in a confined space. This is evident in his pictures ranging from his next film, Repulsion, to his most recent, The Ghost Writer. Even his films that do not seem to fit this schema of limitations have similar components, such as Frantic, which detains Harrison Ford’s American tourist character in Paris, isolating him by his displacement in a foreign country. No matter how expansive or delimited the backdrop, however, Polanski’s characters often chase something only to learn that they themselves are being chased. How many times is Jack Nicholson’s private eye Jake Gittes in Chinatown told something like “you may think you know what you’re dealing with, but, believe me, you don’t,” despite uncovering clue after clue in the involved mystery?

On a more basic level, the film is simply a superb thriller. Every Polanski film can be considered a display of cat-and-mouse relations where the mood shifts from playful to severe with merely a glance or carefully chosen line of dialogue. How profound that the director established this theme with his first film and then continued it throughout his entire career. He makes such stories all the more thrilling by limiting the number of characters and enclosing them in a confined space. This is evident in his pictures ranging from his next film, Repulsion, to his most recent, The Ghost Writer. Even his films that do not seem to fit this schema of limitations have similar components, such as Frantic, which detains Harrison Ford’s American tourist character in Paris, isolating him by his displacement in a foreign country. No matter how expansive or delimited the backdrop, however, Polanski’s characters often chase something only to learn that they themselves are being chased. How many times is Jack Nicholson’s private eye Jake Gittes in Chinatown told something like “you may think you know what you’re dealing with, but, believe me, you don’t,” despite uncovering clue after clue in the involved mystery?

Polanski had wanted to play the role of the drifter himself, as clearly it was with this character that the director most sympathized, hence the drifter’s insolent attitude toward tradition and his ability to survive. But the producers at the small backing studio, Kamera Productions, refused to allow the first-time filmmaker (despite Polanski’s experience as an actor before his attendance at Lodz) to spread himself thin both behind and in front of the camera. As a result, Polanski was never quite satisfied with Malanowicz’s delivery, and he dubbed his own voice over the actor’s for the final print. Casting the husband was easy, as Niemczyk was an experienced performer who at times embodied his character offscreen, ever the experienced-by-age actor’s actor. But for the wife, Polanski found the completely inexperienced Umecka at a public pool. Her greenness became a problem when she failed to acquire the desired reaction time and again. During the scene where she changes and, unbeknownst to her, the Malanowicz’s character watches, Polanski had to fire a gun behind her head to achieve a look of surprise when eventually she does notice the drifter. Regardless, her cold demeanor, albeit unintentional, captures the characterization of a detached bourgeois.

Filming on a 35-foot yacht, the shoot was cramped. While the boat could comfortably support a handful of people (that is, unless they happen to be the characters in the film), it could scarcely bear three actors and an entire film crew, even the negligible crew that Polanski had opted to use on this production. On more than one occasion, cast, crew, and equipment were tossed into the lake due to high winds or mishaps from the tight quarters. From the overcrowded set, Polanski innovated with clever compositions that kept one character in close-up in the foreground watching the other two in the background exchanging dialogue. This shot, repeated throughout the film, becomes its distinct signature. After visiting the set, a journalist from the magazine Ecran wondered “For Whom and for What?” in a piece that deemed the film unnecessary, immoral, and “a colossal waste of Polish taxpayers’ money.” Such anti-buzz before the film’s debut did not sit well with the ministry of culture. When it was eventually screened by the ministry, they griped about the nudity and ambiguous ending. Quite famously, state party secretary Wladyslaw Gomulk tossed an ashtray at the screen in displeasure.

Polish critics dismissed the film upon its release, citing, among other concerns, Krzysztof Komeda’s defiantly jazzy score set against the unforgiving mood of the story. Polanski fled to Paris with his unwanted film just as the drifter skips away across the logs, abandoning the Polish establishment to find his own way. In Poland, he was considered not only rebellious for his film, but a failure, having dropped out of Lodz before graduating. Polanski had completed the 5-year program, save for the written thesis; he had what he needed, being the technical know-how and desperate desire to follow his directorial ambitions, and needed no diploma to justify himself as a filmmaker. While living in France, the small film company Kanawha imported Knife in the Water to the U.S. for a run at the first annual New York Film Festival. Polanski was largely dismissed because he appeared ten years younger than his actual age, until suddenly, in the last nights of the festival, his little foreign thriller was seen on the cover of the September 20, 1963 issue of Time. The film went on to earn an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film at the 1964 Academy Awards, losing to Federico Fellini’s 8 ½.

Polish critics dismissed the film upon its release, citing, among other concerns, Krzysztof Komeda’s defiantly jazzy score set against the unforgiving mood of the story. Polanski fled to Paris with his unwanted film just as the drifter skips away across the logs, abandoning the Polish establishment to find his own way. In Poland, he was considered not only rebellious for his film, but a failure, having dropped out of Lodz before graduating. Polanski had completed the 5-year program, save for the written thesis; he had what he needed, being the technical know-how and desperate desire to follow his directorial ambitions, and needed no diploma to justify himself as a filmmaker. While living in France, the small film company Kanawha imported Knife in the Water to the U.S. for a run at the first annual New York Film Festival. Polanski was largely dismissed because he appeared ten years younger than his actual age, until suddenly, in the last nights of the festival, his little foreign thriller was seen on the cover of the September 20, 1963 issue of Time. The film went on to earn an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film at the 1964 Academy Awards, losing to Federico Fellini’s 8 ½.

Mia Farrow, star of Polanski’s paranoid horror film Rosemary’s Baby, once called the director “important to all humanity,” whereas his more irrational critics call for his castration. A mesh of many personalities, Roman Polanski defies social convention in all arenas, a characteristic that developed long before Knife in the Water and continued long after it. His first few U.S. films were part of the 1960s movement that rebelled against Hollywood establishment, and the press, who sensationalized his unruly behavior offscreen and even embraced it, helped him earn the reputation of a mischief-making scoundrel, albeit a master director. His public image painted with acts of sexual promiscuity and questionable activities, Polanski also speaks five languages and makes films like a true wunderkind. Capable of material ranging from the psycho-sexual horror tale The Tenant, to harrowing dramas like The Pianist, how could any cineaste look upon Polanski’s career without equal parts marvel and uncertainty? Is he a genius? Is he a freak? Why can he not be both and still command our respect, at least from a purely cinematic perspective?

Worth acknowledging but not dwelling upon as some kind of film historian’s skeleton key, the biographical connection between Roman Polanski and his films is both unmistakable and inconsequential. His life adds another dimension to his already complex films, suggesting the origin of the director’s thematic preoccupations. But in each case, his films also require no biographical explication; from this arguably dismissive standpoint, his films operate on their own esteem as thrillers and dramas and the darkest of dark comedies. Polanski’s first great film of many, Knife in the Water does not require analysis of the director’s past to appreciate. Although, an understanding of his early life assists the viewer to see Polanski as the drifter, prancing across the logs to escape and, perhaps, later enroll in Lodz, only to escape once more to France and then Hollywood, and then back to France. Coexisting in irony and tragedy, the Polanski curse of having his films scrutinized against his personal life sidetracks his detractors from the work itself, while also allowing his films to flower for those who objectively embrace his cinema.

Bibliography:

Leaming, Barbara. Polanski, The Filmmaker as Voyeur: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Parker, John. Polanski. London, 1994.

Polanski, Roman. Roman by Polanski. New York: Morrow, 1985.

Sandford, Christopher. Polanski: A Biography. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review