The Definitives

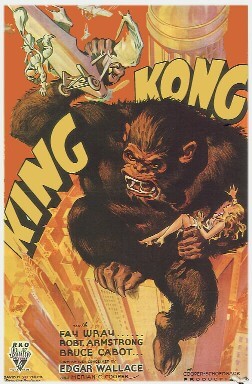

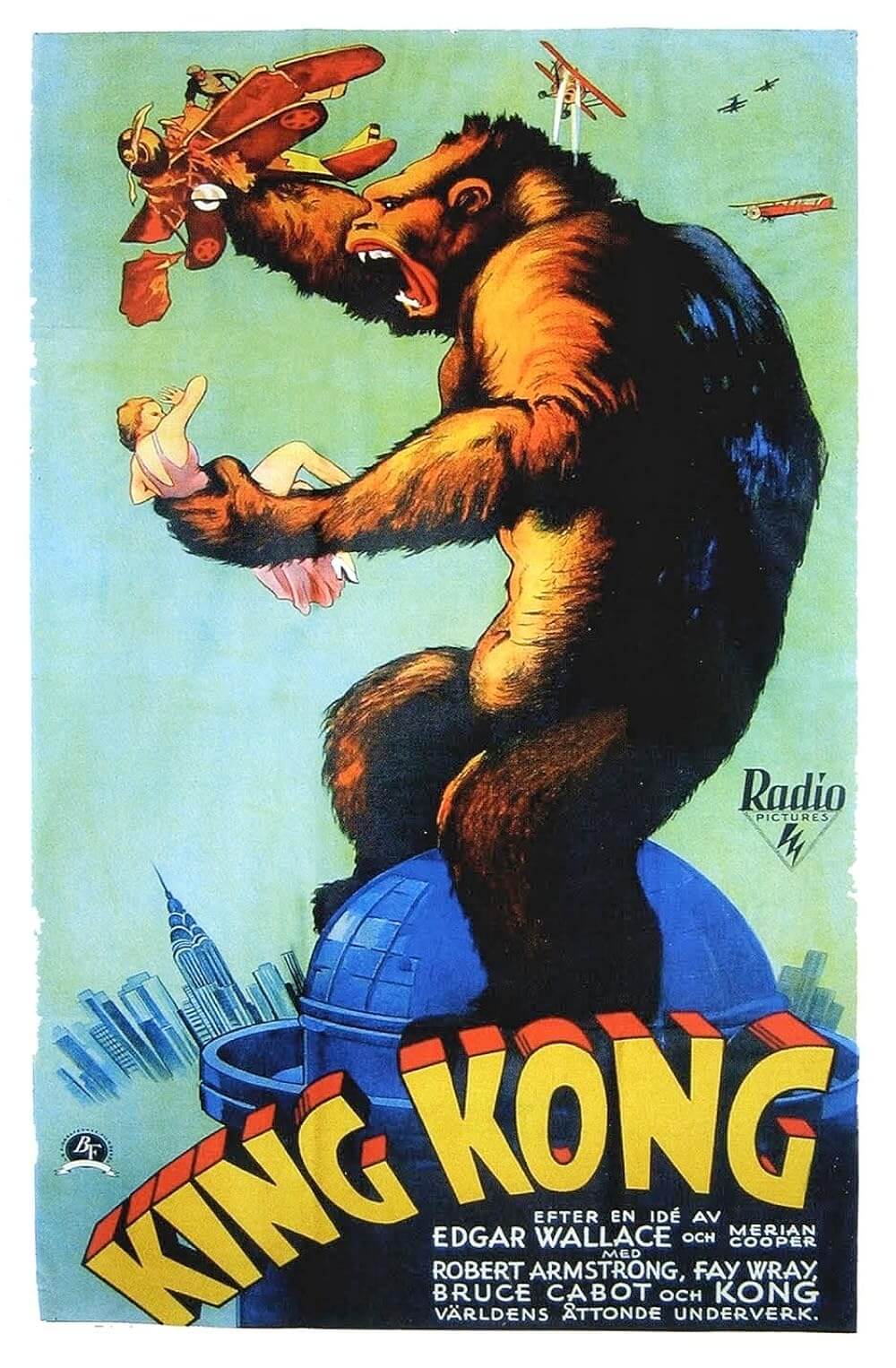

King Kong (1933)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Hailed for “out-thrilling the wildest thrills,” Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s 1933 classic King Kong delivers an essential component of Hollywood cinema: escape. Released during the dog days of the Great Depression, the film boasts crowd-pleasing escapism that transported audiences to the faraway Skull Island, where they could forget their troubles and lose themselves in its mixture of travelogue and primal adventure. As an object of film history, its innovations in special FX and stop-motion animation remain groundbreaking achievements, while its iconography and mythology have continued to inspire remakes and re-imaginings to this day. Even the name “King Kong” has a life of its own, synonymous with enormity and grandiosity. In addition to King Kong’s legacy, the film invites decoding. It has been seen as a parable for the modern world conquering the uncivilized; others see this story, about a colossal black ape who falls in love with a blonde woman, as a coded text that reflects racial dynamics in America during the 1930s. Whether the story ends with King Kong falling from atop the Empire State Building as a symbol of black otherness whose death restores white order, as some cultural critics have suggested, or as a tragic look at the violent outcomes of a racist society given the ending’s somber tone, remains an open debate. Conflicting evidence from the life and writings of Cooper, the film’s author if just one can be assigned, fuels these discussions. But King Kong’s power as a cinematic fantasy resides in its rich symbolic potential as a text; the sublime creature has inspired no end of interpretations and reactions from its audience. With its iconic, distinctly cinematic imagery and mythology, few films have ever reached these sustained heights.

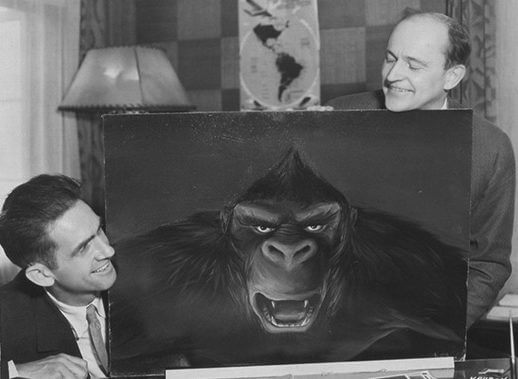

King Kong was the brainchild of Merian C. Cooper, a showman whose life story, even in the abbreviated form below, reads like a Hollywood adventure highlight reel. A “man of action,” Cooper was born in 1893 to an established Southern family. He spent most of his adult life leaping from one adventure to the next as a pilot, freedom fighter, explorer, and chronicler of unseen tribes the world over. Following his expulsion from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in his early years, he served as a crime reporter in the Midwest, but always with the hope of joining the First World War in Europe. He considered himself a patriot and felt a restless need to see action. He got his chance as a bomber pilot in the U.S. Air Service, where his plane was shot down by German forces, resulting in a horrific plane crash and premature declaration of his death. After escaping the crash with his life and surviving the war, Cooper continued fighting in Europe for the Kościuszko Squadron in Poland during their war with the Soviets. While there, he survived yet another plane crash only to become a prisoner in a Russian POW camp for nine months. In captivity, he wrote a book about his experiences that demonstrated his natural flair for storytelling, which, when he finally returned home (after a daring escape from the Soviet camp), landed him a post with The New York Times as a travel reporter. On assignment, he paired with photographer Ernest Schoedsack, whom he first met in Vienna during the war, to produce a story about the Ethiopian Empire for the American Geographical Society, earning his entry into the Explorers Club of New York in the process. By his early thirties, Cooper was already a war hero, a seasoned reporter, a pilot with an interest in commercial aviation, and an explorer who would find himself drawn to film in the ensuing years.

Cinema’s Rough Riders, Cooper and Schoedsack would collaborate on several pictures over the next three decades. Cooper’s biographer Mark Cotta Vaz emphasizes their criteria of “distant, difficult, and dangerous” stories from an unequivocally Western, unmistakably white ideological perspective. In the 1920s, a decade before their cinematic fantasies like King Kong, they produced early ethnographic documentaries. With Grass (1925), a project for the American Geographical Society, Cooper and Schoedsack charted the journey of the nomadic Bakhtiari tribe. The filmmakers put themselves at considerable risk to follow a caravan of 50,000 crossing treacherous rivers and steep mountain passes in modern-day Iran, taking a now-forgotten trail to find a pasture for their livestock. But similar to Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1925), Cooper and Schoedsack had directed their subjects, interacting not merely as objective observers but participants in dramatized expeditions. Their work on Chang (1927) goes even further, presenting “A Drama of the Wilderness” set in Siam, where a farmer encounters the jungle’s many wild animals. The images of stampeding elephants and an extremely close encounter with a tiger—it comes face-to-face with the camera, thus the viewer—were orchestrated by Cooper and Schoedsack for the camera. Their next production, Paramount Pictures’ 1929 adaptation of A. E. W. Mason’s book The Four Feathers, a favorite of Cooper’s, was shot in Africa and transitioned the filmmakers into pure fiction.

Cinema’s Rough Riders, Cooper and Schoedsack would collaborate on several pictures over the next three decades. Cooper’s biographer Mark Cotta Vaz emphasizes their criteria of “distant, difficult, and dangerous” stories from an unequivocally Western, unmistakably white ideological perspective. In the 1920s, a decade before their cinematic fantasies like King Kong, they produced early ethnographic documentaries. With Grass (1925), a project for the American Geographical Society, Cooper and Schoedsack charted the journey of the nomadic Bakhtiari tribe. The filmmakers put themselves at considerable risk to follow a caravan of 50,000 crossing treacherous rivers and steep mountain passes in modern-day Iran, taking a now-forgotten trail to find a pasture for their livestock. But similar to Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1925), Cooper and Schoedsack had directed their subjects, interacting not merely as objective observers but participants in dramatized expeditions. Their work on Chang (1927) goes even further, presenting “A Drama of the Wilderness” set in Siam, where a farmer encounters the jungle’s many wild animals. The images of stampeding elephants and an extremely close encounter with a tiger—it comes face-to-face with the camera, thus the viewer—were orchestrated by Cooper and Schoedsack for the camera. Their next production, Paramount Pictures’ 1929 adaptation of A. E. W. Mason’s book The Four Feathers, a favorite of Cooper’s, was shot in Africa and transitioned the filmmakers into pure fiction.

Before long, Cooper became self-reflexive about his collaborations with Schoedsack; he envisioned an original story that would transplant the wonder of his own exploratory expeditions into the framework of an irresistible Hollywood spectacle centered around a giant ape. Since childhood, when Cooper read Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa by the French-American anthropologist Paul du Chaillu, he had been fascinated by stories of uncannily large gorillas. The book features an account of scientists venturing into the wild, where they discover gorillas and Pygmy tribes for the first time. This notion of Earth’s unexplored corners intrigued Cooper, compelling him to become an explorer. Cooper also encountered gorillas in Africa while filming The Four Feathers, and his experiences led to his ideas about a fictional adventure and a colossal-sized ape. His ideas continued to materialize after meeting William D. Burden, a famous explorer who shared details about his 1926 expedition to the Dutch East Indies, modern-day Indonesia, in his book The Dragon Lizards of Komodo. There, Burden encountered the 10-foot-long Komodo dragons, which to unfamiliar eyes looked like dinosaurs. Burden later shared his first-hand accounts with Cooper and implanted details that would emerge in King Kong, from the idea of a lizard island to a creature whose name begins with the letter “K”.

Cooper’s idea for King Kong was only original in the sense that it started with him. Both literature and cinema had tapped into the fantasy explorer genre, setting precedents for Cooper’s proposed film. Novels such Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and The Mysterious Island (1874) imagined prehistoric ecosystems where dinosaurs thought to be extinct or undocumented creatures lived in isolation. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Land That Time Forgot (1924) both followed in Verne’s footsteps with their descriptions of other-worldly jungles in the South Pacific or South America. On film, Harry Hoyt’s silent adaptation of The Lost World from 1925 featured crude dinosaurs brought to life by special FX maestro Willis O’Brien. The film’s plot lacked much substance outside of its prehistoric creatures stomping through an undiscovered jungle and later wreaking havoc in downtown London, but it supplied the method and foundation from which Cooper and Schoedsack’s King Kong was born. To be sure, when Cooper eventually pitched his idea, RKO lawyers worried that the film would be targeted by Doyle’s estate in a copyright infringement suit. Both stories, after all, use similar devices: an expedition to an unknown and untamed land; an obsessed leader of the voyage; an attractive young woman and reluctant young man who fall in love along the way; and a return to civilization, where an enormous monster is unleashed on a metropolis. Given the similarities, RKO resolved to buy the rights to The Lost World to avoid any legal action against Cooper’s proposed film.

King Kong’s greatness remains in part because it demonstrates a compendium of Classic Hollywood production strategies. Although it’s perhaps too easy to name Cooper as the film’s sole author, David O. Selznick, the executive producer whose name appears below King Kong’s on the title card, made many of the production’s more extravagant flourishes possible. Selznick had just left Paramount to become head of production at RKO, where he increased the rate of the studio’s output and raised profits by installing individual producers to oversee specific genres—a novel idea that other studios would soon adopt. Having seen Cooper’s earlier ethnographic adventure stories and produced The Four Feathers, Selznick hired him as an executive who would preside over a series of escapist pictures. Cooper’s first project for Selznick was an adaptation of Richard Connell’s 1924 short story, “The Most Dangerous Game,” featuring Joel McCrea and Fay Wray as shipwrecked passengers hunted on an island by a reclusive madman. Released in 1932 from co-directors Schoedsack and Irving Pichel, The Most Dangerous Game featured elaborate sets and exotic locales. In typical Selznick fashion, the production spared no expense. But Cooper had bigger plans to film his long-gestating idea about a giant gorilla on a secluded island, originally titled The Beast. The film’s production would begin with the end of another, called Creation, an over-budget project whose special FX by Willis O’Brien showed promise nonetheless. When Cooper arrived at RKO, he screened test footage from Creation that alternated between human actors and stop-motion dinosaurs, a technique The Lost World used to similar effect several years before. In an impassioned letter, Cooper convinced Selznick to abandon the production due to its dull story; however, he praised O’Brien’s effects crew and suggested they might be used to bring his more exciting idea, The Beast, to the screen.

King Kong’s greatness remains in part because it demonstrates a compendium of Classic Hollywood production strategies. Although it’s perhaps too easy to name Cooper as the film’s sole author, David O. Selznick, the executive producer whose name appears below King Kong’s on the title card, made many of the production’s more extravagant flourishes possible. Selznick had just left Paramount to become head of production at RKO, where he increased the rate of the studio’s output and raised profits by installing individual producers to oversee specific genres—a novel idea that other studios would soon adopt. Having seen Cooper’s earlier ethnographic adventure stories and produced The Four Feathers, Selznick hired him as an executive who would preside over a series of escapist pictures. Cooper’s first project for Selznick was an adaptation of Richard Connell’s 1924 short story, “The Most Dangerous Game,” featuring Joel McCrea and Fay Wray as shipwrecked passengers hunted on an island by a reclusive madman. Released in 1932 from co-directors Schoedsack and Irving Pichel, The Most Dangerous Game featured elaborate sets and exotic locales. In typical Selznick fashion, the production spared no expense. But Cooper had bigger plans to film his long-gestating idea about a giant gorilla on a secluded island, originally titled The Beast. The film’s production would begin with the end of another, called Creation, an over-budget project whose special FX by Willis O’Brien showed promise nonetheless. When Cooper arrived at RKO, he screened test footage from Creation that alternated between human actors and stop-motion dinosaurs, a technique The Lost World used to similar effect several years before. In an impassioned letter, Cooper convinced Selznick to abandon the production due to its dull story; however, he praised O’Brien’s effects crew and suggested they might be used to bring his more exciting idea, The Beast, to the screen.

The work on King Kong lasted more than a year, a protracted schedule given that most 1930s productions lasted a few months on average. Cooper and crime novelist Edgar Wallace began to discuss the story in late 1931, and the film arrived in theaters in early 1933. Cooper’s initial ideas about a giant ape ballooned after seeing O’Brien’s footage from Creation; more than just an ape island, the new concept would feature a prehistoric world populated with all manner of creatures. Like many Classic Hollywood screenplays, several writers contributed to King Kong, and many have since claimed majority authorship over the end product, resulting in disputes over the years about who actually wrote the film. Though Wallace penned an initial draft, titled Kong, that allowed production to get underway, his sudden death in early 1932 meant other writers, including the credited James Creelman and Ruth Rose (Schoedsack’s wife), as well as uncredited contributors, supplied substantial material throughout the filming process. Cooper also added to the script, which remained in an unfinished state throughout filming. Suffice it to say, King Kong was a collaborative effort on the page and remained a work-in-progress during the shoot, regardless of later claims by the competing estates of those mentioned. As for the actual filming, Cooper and Schoedsack divided their efforts. Schoedsack handled much of the live-action footage and character-based scenes; Cooper worked closely with O’Brien to complete the technical and action sequences.

The screen story follows obsessed motion picture director Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong), who mounts an expedition to the uncharted Skull Island, which is nestled in the Pacific Ocean and shrouded by mystique. The planned film production in this strange, undocumented locale features the fair-haired Ann Darrow (Fay Wray) as its star, a performer plucked by Denham from the streets of Depression-era New York City. When Denham’s boat arrives at this fantastical world, they discover a beach isolated from the rest of the island by a gigantic wall. There, they observe black natives worshiping a god called Kong. Once the islanders see Ann, who they call “the golden woman,” they kidnap her as a sacrifice to appease their god, placing her on an altar. Kong, a 50-foot-tall gorilla, emerges from the forest and, enchanted by her hair and skin color, takes hold of Ann and returns with her to his jungle lair. Mounting a rescue, the boat’s crew, led by Ann’s newfound love Jack Driscoll (Bruce Cabot), ventures into the island’s dinosaur-laden territory to get Ann from the enormous gorilla. When Jack finally does save Ann, Kong chases them down, only to be rendered unconscious by Denham’s smoke bombs. Denham’s crew secures Kong and transports the beast back to New York for a Broadway spectacle, featuring “The Eighth Wonder of the World” in chains for an awed crowd of onlookers. Denham introduces Kong, saying, “Ladies and gentlemen… I’m going to show you the greatest thing your eyes have ever beheld. He was a king and a god in the world he knew, but now he comes to civilization, merely a captive—a show to gratify your curiosity.” All at once, Kong escapes his shackles to wreak havoc on the city; he topples automobiles and a commuter train, and he locates Ann, taking back his prize. He all but conquers the metropolis when he climbs atop the Empire State Building, Ann in hand. For a brief moment he stands defiantly atop the tallest building in the world at the time. And when planes attack Kong and he falls to his death, Denham arrives on the scene and proclaims, “It was beauty killed the beast.”

The film would become one of cinema’s special FX marvels, as Cooper and Schoedsack employed every trick in the book, and some not yet written, to realize their monumental adventure. A combination of miniatures, traveling mattes, animation styles, rear-projected backgrounds, and other techniques each disappear into one another to create an incomparable magic show, where the impossible lives and breathes on the screen. The success of King Kong’s visualization belongs to O’Brien, whose techniques on The Lost World and the scrapped Creation landed his crew the job of a lifetime. O’Brien worked alongside Marcel Delgado, who designed the Kong puppet, to bring the great ape to life with an 18-inch miniature that he painstakingly adjusted by hand using the stop-motion process. He also used an 18-foot model of Kong from the shoulders up; operated by three technicians, the larger model was used for shots that were closer or included human actors. Kong’s persona was built little by little, creating the suggestion of movement and personality through a meticulous progression. Yet, his character is pieced together from a metal skeleton frame, foam, and animal fur, making him an unlikely source of the audience’s sympathy. But miraculously, Kong conveys a singular character in motion pictures, his love for and fascination with Ann Darrow unmistakable, his final look at Ann before his death painfully sad. There are moments where Kong’s behavior and curiosity is best defined as idiosyncratic but strikingly true, such as when he verifies his Allosaurus kill by flapping its lifeless jaw, or when he smells his fingers after touching Ann. These moments grow throughout the film until the creature is no longer just a beast or a puppet, but the story’s protagonist, elevating the B-grade monster movie into a moving tragedy when Kong falls to his death.

The film would become one of cinema’s special FX marvels, as Cooper and Schoedsack employed every trick in the book, and some not yet written, to realize their monumental adventure. A combination of miniatures, traveling mattes, animation styles, rear-projected backgrounds, and other techniques each disappear into one another to create an incomparable magic show, where the impossible lives and breathes on the screen. The success of King Kong’s visualization belongs to O’Brien, whose techniques on The Lost World and the scrapped Creation landed his crew the job of a lifetime. O’Brien worked alongside Marcel Delgado, who designed the Kong puppet, to bring the great ape to life with an 18-inch miniature that he painstakingly adjusted by hand using the stop-motion process. He also used an 18-foot model of Kong from the shoulders up; operated by three technicians, the larger model was used for shots that were closer or included human actors. Kong’s persona was built little by little, creating the suggestion of movement and personality through a meticulous progression. Yet, his character is pieced together from a metal skeleton frame, foam, and animal fur, making him an unlikely source of the audience’s sympathy. But miraculously, Kong conveys a singular character in motion pictures, his love for and fascination with Ann Darrow unmistakable, his final look at Ann before his death painfully sad. There are moments where Kong’s behavior and curiosity is best defined as idiosyncratic but strikingly true, such as when he verifies his Allosaurus kill by flapping its lifeless jaw, or when he smells his fingers after touching Ann. These moments grow throughout the film until the creature is no longer just a beast or a puppet, but the story’s protagonist, elevating the B-grade monster movie into a moving tragedy when Kong falls to his death.

The film’s innovations reach beyond the obvious special FX, which often dominate the discussion about its influence; the mobile camerawork and sound design also prove ahead of their time. Compare the stationary, mounted shots of The Lost World, typical in silent filmmaking, to the way the camera rushes at Kong during the plane attack sequence in the finale. These movements, however infrequent in King Kong, engaged audiences and confronted them with the monster. Sound technology, too, had only been around for five years when King Kong debuted, and the film was not only one of the first talkies to maintain a dramatic score throughout, supplied by Max Steiner, but it experimented with the interplay between diegetic and non-diegetic music. Listen to the aurally complex sequence when Denham’s crew spies on the Skull Island tribe’s Kong ceremony. The film layers the tribe’s thumping drum beat and singing beneath Steiner’s blazing score, resulting in two strains of music playing over the same scene, an audio strategy far more complex than the average 1930s Hollywood film. Elsewhere, the use of sound is more playful, such as when Driscoll and Ann embrace on the boat, and the score blooms with romance—only to drop with an abrupt pause when the shot cuts to the Skipper (Frank Reicher), who calls for Driscoll from inside his cabin. Back to Driscoll and Ann kissing, the music picks up again. Then back to the Skipper, the music stops, and he calls for Driscoll again. The production uses music to guide every emotion, but also to immerse the viewer with convincing sound effects. Similar to the romantic scene between Driscoll and Ann, the sharp halt of a sound results in a reaction during the famous sequence of Kong shaking Denham’s crew from a fallen tree. Their screams follow them into a ravine below until the sound breaks suddenly when their bodies hit the ground. Ann’s piercing scream, Kong’s grumbles and roars, the serpentine hiss of the Allosaurus—each has a distinct personality thanks to sound designer Murray Spivack. None is more haunting than the sequence when Kong searches for Ann in New York; he grabs a random woman and, upon realizing she’s not Ann, drops her from several stories high. As she plummets to her death, her screams fade into a deafening police siren.

By the time production wrapped on King Kong in early 1933, Selznick had left RKO for a position at MGM, and Cooper was made the head of production. Under Cooper’s control, his film had spent almost three times more than the average production at RKO, and the studio’s executives, reeling from their troublesome financial situation in the Depression, had started to worry about costs. Ever the showman, Cooper counteracted the studio’s concerns about the price tag with an aggressive promotional campaign that appealed to the audience’s desire for exotic spectacles and romantic ideas about the spirit of adventure into the “dark” yet-undiscovered corners of the planet. Cooper supplied the media with a detailed press kit that instructed reviewers on how to summarize the film’s plot and talk about its appeal, while he saturated the marketplace with King Kong novelizations, newspaper cartoons, radio plays, and colorful advertising—methods that would later become standard for every major Hollywood production. Each piece of promotional material capitalized on a different element of the story, appealing to a range of demographics. Some dwelled on its “sensational” or “sexy” elements; other items called out its melodramatic aspects and appealed to the huge market of women moviegoers in the 1930s. Theater owners joined in, decorating their lobbies with jungle scenes or even a rented lion in a cage. A significant amount of the original advertising capitalized on the jungle craze, a popular strain of adventures featuring heroes in pith helmets, women in leopard print, and wild animals. Most famous was the Tarzan film series—around since 1918 but raised to new heights by MGM’s Tarzan the Ape Man from 1932, which featured five-time Olympic gold medalist Johnny Weissmüller as Tarzan and Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane. Cooper sought to appeal to every person in the audience, but for all his lavish efforts, King Kong performed only moderately well at the box-office.

Indeed, Hollywood lore sometimes paints King Kong as RKO’s Depression-era savior. But no matter how many elaborate variety-show premieres the film had at Sid Grauman’s Chinese Theater or stage performances that preceded the Radio City Music Hall debut, the film’s initial 1933 release can only be considered a moderate success given the film’s higher-than-average cost. Other films made more in 1933, among them RKO’s adaptation of Little Women, directed by George Cukor and starring Katharine Hepburn. Cooper’s saturation of promotional spaces aside, he had trouble selling the title. As iconic and instantly recognizable as the name King Kong is today, Depression-era viewers had never heard of it. In her book Tracking King Kong, Cynthia Marie Erb quotes a journal entry by Wallace that claims the studio thought the title had “a Chinese sound,” and so Selznick tried to convince Cooper to use the title The Jungle Beast instead. After all, Cooper’s film had not come from a well-established book such as those that inspired Universal Pictures’ 1930s horror gallery: Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. King Kong was not a brand that moviegoers would understand at first glance. It was not until RKO—and studios from MGM to Warner Bros. who had acquired the rights to King Kong at various points over the years—re-released the film into theaters that it began to see enormous profits and create its own mythology.

Indeed, Hollywood lore sometimes paints King Kong as RKO’s Depression-era savior. But no matter how many elaborate variety-show premieres the film had at Sid Grauman’s Chinese Theater or stage performances that preceded the Radio City Music Hall debut, the film’s initial 1933 release can only be considered a moderate success given the film’s higher-than-average cost. Other films made more in 1933, among them RKO’s adaptation of Little Women, directed by George Cukor and starring Katharine Hepburn. Cooper’s saturation of promotional spaces aside, he had trouble selling the title. As iconic and instantly recognizable as the name King Kong is today, Depression-era viewers had never heard of it. In her book Tracking King Kong, Cynthia Marie Erb quotes a journal entry by Wallace that claims the studio thought the title had “a Chinese sound,” and so Selznick tried to convince Cooper to use the title The Jungle Beast instead. After all, Cooper’s film had not come from a well-established book such as those that inspired Universal Pictures’ 1930s horror gallery: Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. King Kong was not a brand that moviegoers would understand at first glance. It was not until RKO—and studios from MGM to Warner Bros. who had acquired the rights to King Kong at various points over the years—re-released the film into theaters that it began to see enormous profits and create its own mythology.

In many discussions about the film, scholars have examined its mythology as racially coded, drawing from Cooper’s history as a white explorer and probable racist. With their early films, Cooper and Schoedsack established their own Orientalist brand of spectacle, exhibiting native peoples for Western audiences eager to see so-called uncivilized cultures on display. The politics of their aesthetic approach relied on a long tradition of anthropological and historical writing from explorers and scholars about “primitive” cultures. Fatima Tobing Rony writes that their mode of representation established in these early films functions as a “teratology,” or study of abnormalities—a viewpoint that all non-white cultures have a certain incongruity and therefore fascinating monstrosity about them. It’s easy to interpret both Grass and Chang as works of ethnographic study, which has been seen as inherently teratologic, where native peoples become specimens rather than fully drawn characters or human beings. This element of Cooper and Schoedsack’s work becomes crucial when viewing King Kong, which is a film about an ethnographic expedition to Skull Island. The racial coding that emerges from the 1933 fantasy is not merely about scholars reading too much into the film’s extratextuality; it’s a troubling reality of the film and its maker.

Cooper’s biographers have noted his racist behavior during his early years; Vaz even downplayed accounts of Cooper whipping black villagers during the shoot of The Four Feathers, arguing his “note of racial superiority was typical of a southern white man who grew up in times when the American memory still recalled the practice of slavery.” Such arguments are hardly comforting after Vaz quotes a segment of Things Men Die For, the book Cooper wrote in the Russian POW camp. Cooper wrote, “The lust for power is in us, we white men. We’ll sacrifice anything for the chance to rule. And I believe that it is right that black, brown, and yellow men should be dominated by the white.” Such rhetoric finds its way into King Kong, as Denham hopes to find “something monstrous” on the island that “no white man has ever seen,” while Driscoll talks about the Skull Island tribe and “heathen tricks” when they show an interest in acquiring Ann. When they eventually subdue Kong, they return him by boat like a captive on a slave ship, “dominated” as Cooper might say. King Kong also exploits the theme of black Otherness preying on white women that was rampant in the early decades of cinema, codified by D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). And though even Griffith acknowledged his film perpetuated hate, the imagery of a black threat and a white innocent had survived. Among the advertising campaigns used to promote King Kong, many of them focused on the idea of a “black monster” and a “white captive,” juxtaposing the formidable gorilla as he holds the innocent “girl” in his oversized hand. In Germany, the film had the title King Kong und die Weisse Frau (King Kong and the White Woman) and became one of Adolf Hitler’s favorites. Though in later years Cooper claimed that he never intended such readings of his film, its roots in Cooper’s colonialist and racist worldview remain unmistakable.

King Kong’s use of a manufactured “Beauty Killed the Beast” motif prompts several sub-themes in the film beyond the notion that white beauty transfixes the black Other, and they warrant exploration. The film establishes the idea in the opening titles with an “Old Arabian Proverb” (written by Cooper): “And the prophet said: ‘And lo, the beast looked upon the face of beauty. And it stayed its hand from killing. And from that day, it was as one dead.’” With the proverb in mind, Ann Darrow does little more than supply the defenseless woman trope, a damsel in distress, even though Fay Wray’s presence elevates Ann. At one point, Denham insists the audience needs “a pretty face” to instill fear of the monster he hopes to capture on film, and Ann does just that, her role reduced to screaming in terror or clinging to Driscoll—who finds women to be a “nuisance” because they “just can’t help being a bother.” Denham’s line in the finale, then, could be seen as placing the blame on a beautiful woman for simply existing, even though it is man’s desire to exploit Nature that causes Kong’s destruction. The “Beauty Killed the Beast” motif also underscores the theme of civilization conquering the wild, the foundational idea behind Manifest Destiny and conquest of the frontier. Cooper came from what he claimed was a conservationist mindset; in his early life, he was determined to explore and document exotic animals and preserve them by killing and stuffing them to learn more, if only as proof of human superiority over Nature. This seems to be Denham’s ambition with Kong—to capture, exhibit, educate, and dominate. When King Kong dies, the modern invention of the machine-gunned biplane renders the animal powerless. Cooper, having flown planes during two wars, even appears in a cameo as the pilot of the plane that delivers the final blow to Kong, asserting that Nature is no match for the modern world.

King Kong’s use of a manufactured “Beauty Killed the Beast” motif prompts several sub-themes in the film beyond the notion that white beauty transfixes the black Other, and they warrant exploration. The film establishes the idea in the opening titles with an “Old Arabian Proverb” (written by Cooper): “And the prophet said: ‘And lo, the beast looked upon the face of beauty. And it stayed its hand from killing. And from that day, it was as one dead.’” With the proverb in mind, Ann Darrow does little more than supply the defenseless woman trope, a damsel in distress, even though Fay Wray’s presence elevates Ann. At one point, Denham insists the audience needs “a pretty face” to instill fear of the monster he hopes to capture on film, and Ann does just that, her role reduced to screaming in terror or clinging to Driscoll—who finds women to be a “nuisance” because they “just can’t help being a bother.” Denham’s line in the finale, then, could be seen as placing the blame on a beautiful woman for simply existing, even though it is man’s desire to exploit Nature that causes Kong’s destruction. The “Beauty Killed the Beast” motif also underscores the theme of civilization conquering the wild, the foundational idea behind Manifest Destiny and conquest of the frontier. Cooper came from what he claimed was a conservationist mindset; in his early life, he was determined to explore and document exotic animals and preserve them by killing and stuffing them to learn more, if only as proof of human superiority over Nature. This seems to be Denham’s ambition with Kong—to capture, exhibit, educate, and dominate. When King Kong dies, the modern invention of the machine-gunned biplane renders the animal powerless. Cooper, having flown planes during two wars, even appears in a cameo as the pilot of the plane that delivers the final blow to Kong, asserting that Nature is no match for the modern world.

With these discussions of King Kong’s thematic readability, it’s often overlooked that the film bears self-awareness as motion picture entertainment. As Vaz noted about Cooper and Schoedsack’s transition from documentary subjects to the fantasy of King Kong, “the ultimate true-life movie expedition team would be making a picture about the ultimate movie expedition.” The film, made by well-established adventurers, follows a thinly fictionalized version of Cooper (Denham) on an expedition to capture something never-before-seen on camera and frame it against a blonde innocent—a dynamic Denham knows will drive audiences wild. Cooper always knew he was making a story about himself, merely adding a layer of myth and movie magic to his own adventures as an explorer. As a result, King Kong is an unlikely film-about-film, open in its discussion of screen tests, cameras rolling, costume changes, Denham’s previous jungle pictures, and the business of box-office (when Denham captures Kong, he declares, “We’ve found something worth more than all the movies in the world!”). Denham even discusses the “Beauty and the Beast” theme of his proposed film ad nauseum, to the extent that he catches himself pontificating in a comic moment (“I’m going right into a theme song here,” he says). It’s as though Cooper and Schoedsack remark on the heavy-handedness of their own theme, which, oddly, does not neutralize its power in King Kong.

The film’s ability to mean something different for each viewer has fueled its survival from the convincing arguments of scholars who have observed the film’s racist overtones. King Kong is a cipher that demands decoding. It also presents an easy target given the social and technical developments made since 1933. Modern-day viewers might balk at the stop-motion effects, having seen the updated, often photorealistic, computer-generated sensations in Peter Jackson’s excellent 2005 remake. Detractors might also focus on the questionable depictions of Skull Island’s black inhabitants dancing about in gorilla suits, the boat’s painfully stereotyped Chinese cook, or its limited uses for women. Some might question the varying sizes of Kong, as he seemingly grows from 20 feet tall on the island to about 50 feet tall atop the Empire State Building. But these problematic portrayals and poetic licenses are simply absorbed by viewers willing to indulge their imaginations and transport themselves to a fantastical time and place. The sheer size and iconography of King Kong melts away the subtexts upon revisiting the film, allowing the power of its imagery to survive its many instructive interpretations through the lenses of Cooper’s biography, racial representation, and symbolism.

The timelessness of King Kong remains its ability to bring audiences to the brink of danger, and then, by the end, return them to safety. This escapist agenda drives much of Hollywood cinema and sustains its appeal. Cooper understood that Depression-era moviegoers needed to escape their poverty and financial distress and face something even more alarming, but it was also important to return them to the safety of the world when the adventure was over. “Heaven help us all!” an original lobby card exclaimed, “King Kong, the ape as big as a battleship, is loose!” Audiences would flock to movie houses, then, to submit themselves to a danger worse than their own living conditions, if only to be reassured of some order in the universe. Consider the notoriously lost “spider pit” sequence in King Kong where, after Kong knocks his human pursuers off a log into a chasm, the survivors are eaten by a giant-sized spider, a crablike creature, a lizard, and an octopus. When the film was pre-screened in California, audiences were appalled by the display of death in this scene, prompting Cooper to cut the footage to appease censors. Though the sequence is believed lost, its effect remains a crucial example of how Cooper and Schoedsack endeavored to manipulate their audience. The filmmakers never sought to scare them out of their seats as the “spider pit” would have done; instead, they brought their viewers to the brink of acceptable danger. Even without the benefit of arachnids and octopi, Kong does enough damage on his own; he chews victims apart, smashes them with his fists, and crushes them under his feet. King Kong is an exceedingly violent film, more than one might expect from a 1930s picture, complete with oozing dinosaur blood, innocent victims, and death abound. Nevertheless, the filmmakers restore order by the final shot of Kong’s corpse.

The timelessness of King Kong remains its ability to bring audiences to the brink of danger, and then, by the end, return them to safety. This escapist agenda drives much of Hollywood cinema and sustains its appeal. Cooper understood that Depression-era moviegoers needed to escape their poverty and financial distress and face something even more alarming, but it was also important to return them to the safety of the world when the adventure was over. “Heaven help us all!” an original lobby card exclaimed, “King Kong, the ape as big as a battleship, is loose!” Audiences would flock to movie houses, then, to submit themselves to a danger worse than their own living conditions, if only to be reassured of some order in the universe. Consider the notoriously lost “spider pit” sequence in King Kong where, after Kong knocks his human pursuers off a log into a chasm, the survivors are eaten by a giant-sized spider, a crablike creature, a lizard, and an octopus. When the film was pre-screened in California, audiences were appalled by the display of death in this scene, prompting Cooper to cut the footage to appease censors. Though the sequence is believed lost, its effect remains a crucial example of how Cooper and Schoedsack endeavored to manipulate their audience. The filmmakers never sought to scare them out of their seats as the “spider pit” would have done; instead, they brought their viewers to the brink of acceptable danger. Even without the benefit of arachnids and octopi, Kong does enough damage on his own; he chews victims apart, smashes them with his fists, and crushes them under his feet. King Kong is an exceedingly violent film, more than one might expect from a 1930s picture, complete with oozing dinosaur blood, innocent victims, and death abound. Nevertheless, the filmmakers restore order by the final shot of Kong’s corpse.

King Kong made technological leaps and bounds to deceive viewers into feeling something for its title character, while demonstrating to other filmmakers that the medium had no limits. Whatever a screenwriter could dream up, Hollywood could bring it to the screen. Cooper would remain at the forefront of filmmaking technology after this film. He was a staunch supporter of Technicolor advances, widescreen exhibition, and spent the final years of his film career promoting his latest cause, the expensive and doomed Cinerama process. Other filmmakers have tried to capitalize on his example, using Kong imagery in sequels, remakes, and spin-offs that attempt to introduce new innovations in film technology and special FX—but almost never with the same transportive effect. Cooper and Schoedsack tried to extend King Kong fever with the forgettable sequel, Son of Kong (1933), followed much later by Mighty Joe Young (1949), a pleasant rehash of the original concept on a smaller scale. Over the years, Kong has appeared alongside other colossal monsters, such as Ishirô Honda’s King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). Various Hollywood studios have tried to remake the film with bigger budgets, including Dino De Laurentiis’ abortive 1976 guy-in-a-gorilla-suit version, followed by its silly 1986 sequel, King Kong Lives. Only several decades later, when the industry’s technologies improved enough to produce convincing CGI characters like Gollum from Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings films, would moviegoers be so emotionally invested as they once were, and still are, with Cooper and Schoedsack’s film. Jackson’s remake of King Kong offers the most compelling example of the Kong character having a potent, achingly emotional authority over the audience, whereas Kong: Skull Island (2017) made its giant ape into an unempathetic movie monster.

In her discussion of the original film, Valerie Frazier argues that Jackson’s version “fails to have the same cultural import as the 1933 or 1976 versions because in its sanitized, politically correct form King Kong loses much of its signification power.” Whether or not one agrees with Frazier’s critique of Jackson’s film, her remarks acknowledge that the original King Kong was an adventure to spark the imagination of both general audiences and scholars, raising questions about its legacy and affirming its richness as a text. Working in a place and time when some of the world seemed filled with mysteries, Cooper and Schoedsack served as pioneers, envisioning “distant, difficult, and dangerous” stories and developing the cinematic techniques to realize them. By taking their audience to the brink of the unknown, the filmmakers invented the modern concept of the showman’s spectacle, which has inspired countless directors from Jackson to Steven Spielberg. Within its splendid sense of awe and its ability to involve the viewer emotionally through its technical innovations, King Kong provides the underlying ambition of Hollywood cinema. The film brings the movies to a colossal and iconographic highpoint of entertainment, acknowledging within the narrative and its symbols how eagerly audiences seek out diversion, and how amusement, if visionary talent assembles the production, can have greater significance than mere escapism.

Bibliography:

Cooper, Merian C. Things Men Die for. G. P. Putnam, 1927.

Erb, Cynthia Marie. Tracking King Kong: a Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Wayne State University Press, 2009.

Frazier, Valerie. “King Kong’s Reign Continues: King Kong as a Sign of Shifting Racial Politics.” CLA Journal, vol. 51, no. 2, 2007, pp. 186–205. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44325418. Accessed 1 Apr. 2020.

Goldner, Orville and George E. Turner. The Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic. A.S. Barnes, 1975.

Morton, Ray. King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2005.

Rony, Fatimah Tobing. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Duke University Press, 1996.

Snead, James A. White Screens/Black Images: Hollywood From the Dark Side. Routledge, 1994.

Vaz, Mark Cotta. Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villard, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review