The Definitives

Kagemusha

Essay by Brian Eggert |

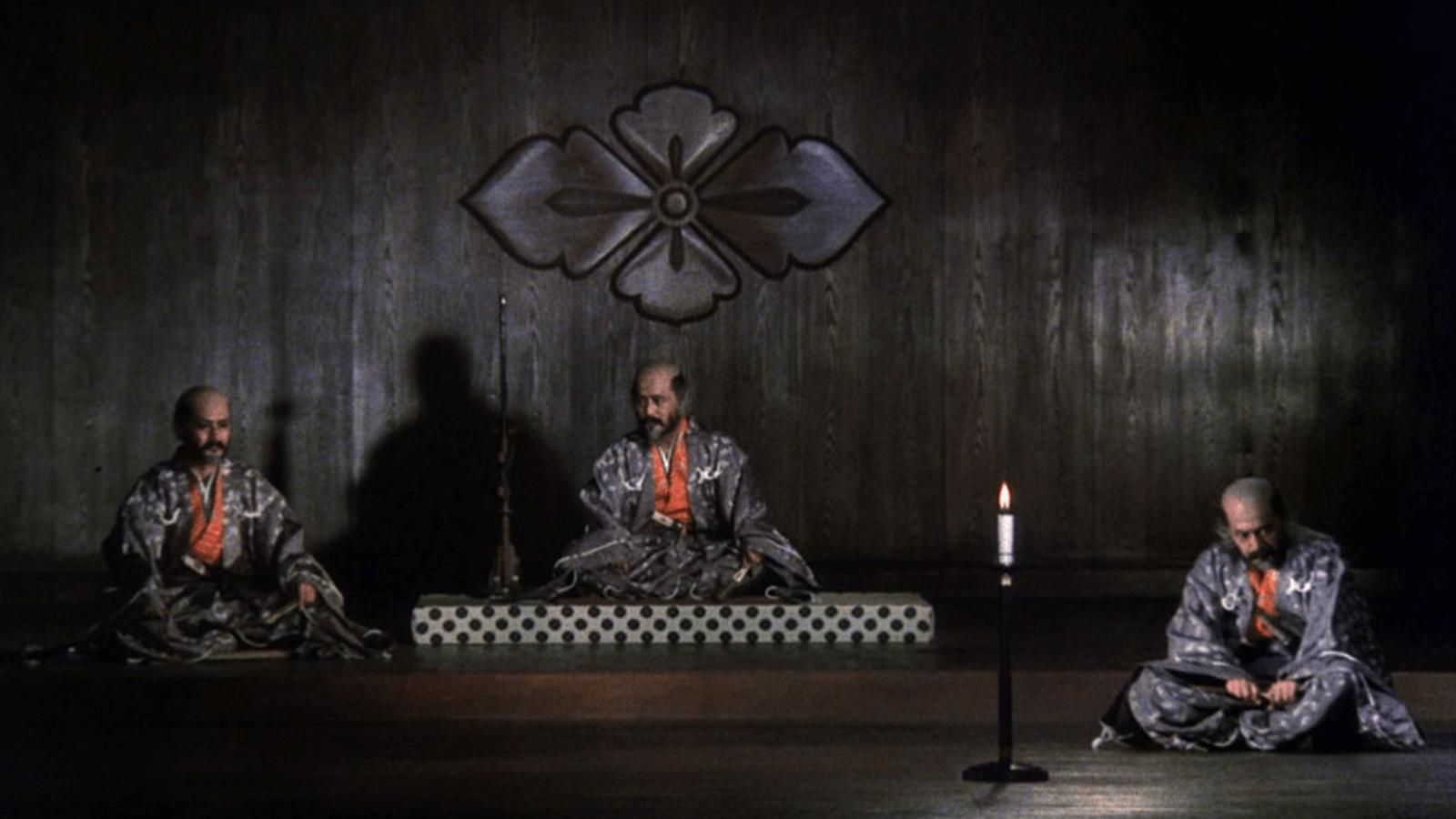

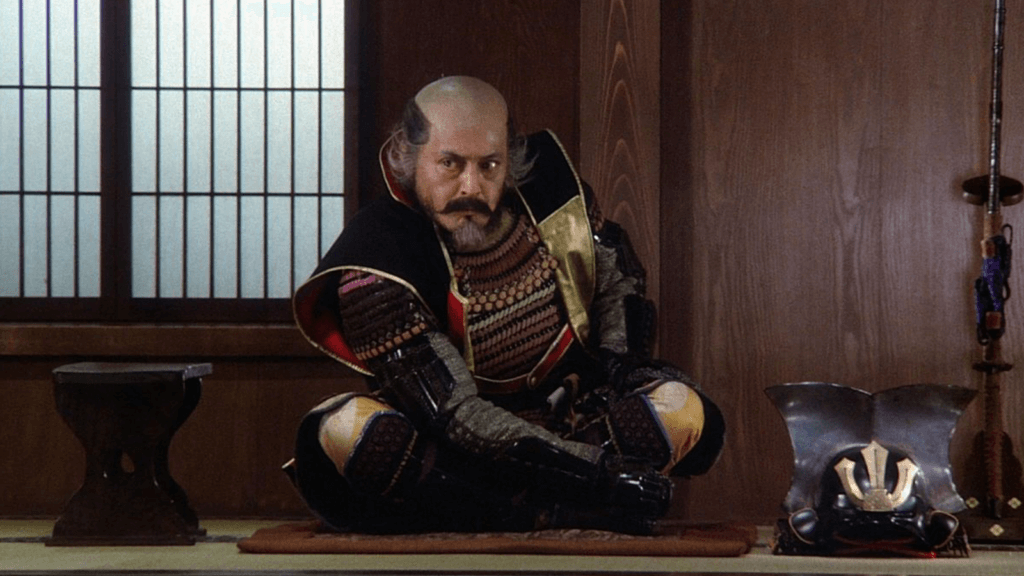

Kagemusha opens with a six-minute shot, the longest of director Akira Kurosawa’s career. Shingen Takeda, a Japanese feudal lord known as a daimyo, sits on a platform, center frame. Two almost identical-looking men sit opposite him in the frame, and all three face out as though on a stage. To Shingen’s right sits his brother, Nobukado, who often dresses like his sibling to deceive their enemies. His back straight, Nobukado strokes his mustache in a gesture mimicking Shingen. Seated both in front of and to Shingen’s left is a thief, hunched and looking downward; he bears an uncanny resemblance to Shingen and has been made up to resemble the daimyo. Together, they look like triplets. Both Shingen and the thief are played by the same actor, Tatsuya Nakadai. Achieved with a convincing split-screen effect, the shot presents reality and illusion; Shingen next to his kagemusha, meaning “shadow warrior,” or double. The dialogue in the sequence notes the minor differences between the men, but by the end of Kurosawa’s epic, the distinctions between the lord and his doppelgänger will be all but eradicated. Reality and illusion will be indecipherable, at least in how the thief sees himself and behaves. Kagemusha is a film about how a fantasy can become real, expressing the director’s career-long obsession with how chimerical beliefs can dramatically alter how one perceives reality.

Whether making a scopic adventure or adapting classical literary material to a Japanese setting, Kurosawa told stories about the human condition, albeit from his pessimistic and bleak view of humanity. His reputation for period epics such as Seven Samurai (1954) or The Hidden Fortress (1958) earned him popularity abroad, but his stories hardly aggrandize Japan’s heroes. For instance, Kurosawa never made films about Japan’s heroic Motonari Mōri nor the Loyal Forty-Seven Ronin, though many of his contemporaries did. Instead, he chose more complex historical incidents and mined them to explore his preoccupations and cynicism, in effect going against convention and tradition to propose an alternate take on history, often underlined by shaken worldviews and protagonists who die tragically. This theme would recur throughout his filmography, with the main characters in Ikiru (1952), Throne of Blood (1957), and many other features dying or predicted to die early in their respective films. Kagemusha features Nakadai as a thief and suspected murderer who finds a new identity by posing as Lord Shingen, and, in that, discovers his purpose by embracing an illusory sense of self. Kurosawa identified with the thief in his film; he reminded the director of how mimetic illusions of reality could become just as powerful as the real thing. At this point in his life, the theme provided a necessary reminder of why he loved making movies.

Kurosawa made Kagemusha during a rocky period in his career. Following the failure of his first color feature, Dodes’ka-den (1970), about vagabonds inhabiting a landfill, the director attempted suicide. He narrowly survived slashing his throat and wrists with a razor several times, and the usually prolific filmmaker would not direct again for five years until Dersu Uzala (1975). But his suicide attempt was not, as in the case of many Japanese artists, an expression of his artistic completion. As Japanese scholar Donald Richie notes, Buddhism often views death as an expressive act, “a natural, logical, and permanently available response to experience and to the exhaustion of life’s possibilities. It implies neither shame, nor trauma, nor defeat.” For artists such as Yukio Mishima or Yasunari Kawabata, who took their own lives, not to mention kamikaze pilots or ronin, samurai warriors who have reached the end of their usefulness to their master or lack thereof, suicide is an act of self-control. It’s a final statement of honor or an artistic life. But in Kurosawa’s case, his life had become wrought with difficulty at home; in his sixties, his eyesight and general health were declining, and, professionally, his future was uncertain.

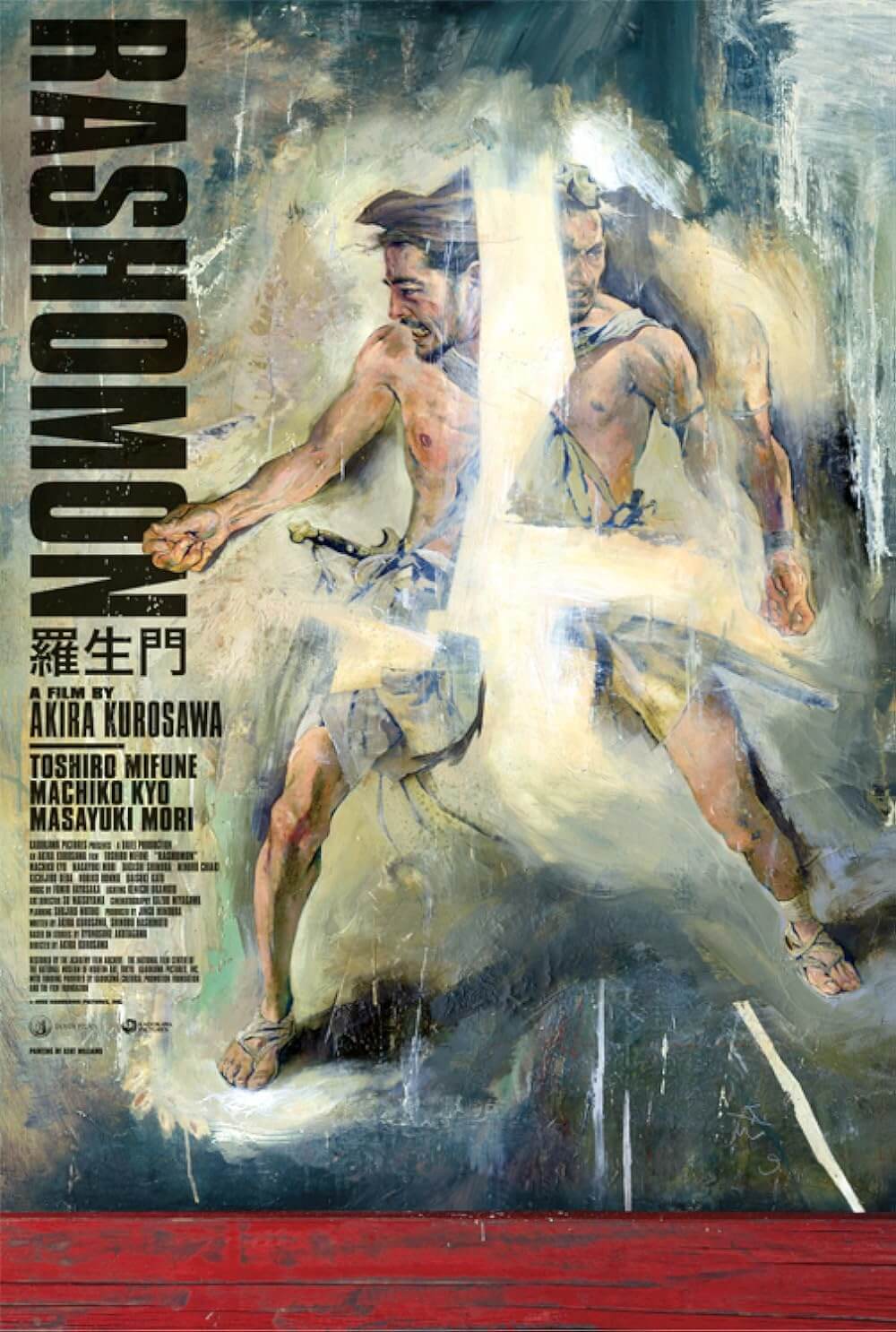

Not only had Dodes’ka-den failed to perform at the Japanese box office, but its chilly reception suggested that his faculties as a filmmaker were not what they used to be. In the years before his suicide attempt, Kurosawa had spread himself thin and experienced several downward shifts in his career. His critical and commercial hit with Red Beard (1965) marked his final collaboration with star Toshiro Mifune, with whom he had made 16 films, including Rashomon (1950) and Seven Samurai. Reeling from their separation—which stemmed from their mutual stubbornness, need for control, and desire for something more, something different—Kurosawa, like Mifune, courted Hollywood. The director’s screenplay for a thriller, Runaway Train, would have been his first English-language feature, but it failed to materialize in the 1960s; the Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky eventually produced Kurosawa’s screenplay in 1985. Kurosawa also spent many months working with 20th Century Fox to develop Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), a war movie about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor told from both sides, only to watch as Fox truncated the screenplay by nearly two hours, switched co-directors, and mettled in every decision. The stress drained his energy; he left the project, and lesser directors replaced him. Accustomed to having complete and meticulous control, Kurosawa felt helpless.

After his suicide attempt, Kurosawa found that acquiring financing for a new film project in the changing Japanese film industry had become impossible. He was no longer the commercially viable filmmaker he had been, and the large budgets for his usual brand of historical epic were now considered impossible. This fall from grace and a changing industry represented a demoralizing reality that left him uncertain and hopeless. Some measure of emotional reprieve appeared in Dersu Uzala, a project spearheaded by the Soviet Union’s Mosfilm, which provided most of the funding, apart from minor contributions from a Japanese investor. With its story about a group of Russian soldiers on a survey mission who are rescued by a wise Goldi hunter, the film performed modestly, yet the production, though rather exceptional, was considered a minor effort. Another five years passed, during which Kurosawa worked on his script for Ran (1985) and another based on Edgar Allen Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death,” which was never produced. He had also been collaborating with Masato Ide on Kagemusha, a project he had been writing and visualizing in hundreds of elaborate drawings and paintings—Kurosawa was a trained painter—planning out every costume, setting, shot, and sequence with renewed interest.

Part of Kurosawa thought Kagemusha would never happen; regardless, he enjoyed creating drawings and paintings at his table, and he was resigned that they may be the only visual evidence of the film he had envisioned in his mind. Casually, he began to reach out to potential backers. He found the proposed budget was too high for Japanese studios and most foreign investors, except for the Americans. On a trip to Hollywood, Kurosawa met with Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas. Both filmmakers had been passionate Kurosawa fans since his work started to appear on college campuses and arthouse theaters in the 1950s and 1960s. After all, Lucas had made his fortune on Star Wars (1977), a film that none-too-subtly borrows from Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress and other works, without credit. Even Lucas’ term for his science-fiction knights, known as “Jedi,” is a homophone based on jidai-geki, the word for a Japanese period drama. Coppola and Lucas had just started American Zoetrope, and their influence in Hollywood was immeasurable. Together, they helped broker a deal between 20th Century Fox and Toho Films to ensure Kurosawa’s latest project had financial backing, using James Clavell’s best-selling 1975 book Shogun, and the bidding war over the adaptation rights, as evidence of the audience’s interest in samurai period epics.

Though financing Kagemusha had worked out, little about the production went smoothly. Kurosawa’s cameraman, Kazuo Miyagawa, who had shot Yojimbo (1961) for the director and several entries in the ongoing Zatoichi series, about a blind swordsman, began suffering from his own failing eyesight due to his diabetes. Kurosawa replaced Miyagawa with two cinematographers, Takao Saito and Masaharu Ueda. Kurosawa had planned for the star of the Zatoichi series, the largely comic actor Shintaro Katsu, to play Shingen and the thief. But Katsu left the production after showing up on the first day with a personal video crew to record his performance, a tool to ensure he was performing up to his standards. Kurosawa said that he would provide feedback and rebuffed the video crew. The director and star could not agree on an accommodation, and Katsu left the project. It was perhaps a blessing since Kurosawa replaced him with Tatsuya Nakadai—one of Japan’s greatest dramatic actors. The two had worked together before, with Nakadai making memorable appearances in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, Sanjuro (1962), and High and Low (1963). But this meant the production would be delayed several months to accommodate Nakadai’s busy schedule of stage acting, and from that, Nakadai brings an appropriate theatricality to his performance.

During pre-production, Kurosawa scouted locations in Japan, but industrialization and development had changed the landscape in recent years. Whereas Kurosawa could have found a forest or rolling hills just outside of Tokyo a couple of decades before, they had since been replaced by highways and buildings. He resolved to shoot on the northmost island of Hokkaido despite having to arrange shots around the island’s castles to avoid filming power lines and contemporary structures. The production needed massive fields for battle scenes, ancient castles, and hundreds of extras. Each was hand-picked by the director. Kurosawa shot Kagemusha over nine months, and it became one of his most difficult productions. At one location, he faced a bomb scare; elsewhere, a typhoon hit Hokkaido and caused significant delays. Challenges aside, Kurosawa, then nearly 70, showed the vigor of a younger director, helping crews prepare sets by erecting structures and engaging in manual labor. The director was doing what he loved. He even reached out to an old friend, his former assistant, Ishirō Honda, who had made a name for himself directing Godzilla (1954) and several other kaiju pictures before retiring in 1975. Kurosawa convinced Honda to return to work as his assistant and creative collaborator, and he often helped the director, whose eyesight was waning. The two worked on Kurosawa’s last five features together. Despite its many challenges, Kagemusha’s production went only one week over schedule, but serving as his own editor, Kurosawa cut the film as he went and completed the final edit just three weeks after wrapping principal photography.

Kagemusha’s production exceeded its budget, and the cost rose to $7 million, becoming the most expensive Japanese production ever at the time. The price tag was more than seven times the usual cost of a Japanese film in 1980, which made Toho nervous. Nevertheless, the collaborative experiment between Japanese and American studios worked. Kagemusha, which Kurosawa proudly declared to the press as “the first Japanese film released worldwide by a major American studio,” earned $10 million at the box office, making it one of the year’s top earners in Japan. However unfair that studios often consider box-office performance a sign of success, Kurosawa had proven himself once again. When the film competed at the Cannes Film Festival in 1980, it earned widespread praise and shared the Palme d’Or with Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. Regardless, the distributors trimmed the international cut of Kagemusha for commercial reasons, much to Kurosawa’s dismay. Several scenes were shortened or removed altogether, including half of the long sequence that surveys the battlefield in the finale. Even so, retrospectives and reassessments celebrated Kurosawa’s legacy, but the director refused to rest on his laurels. If he worked more slowly now in his old age, he would continue making films for over a decade.

Kurosawa and Ide developed their script from a historical account of the Sengoku period of feudal Japan, where Shingen Takeda (1521-1573) hired a look-alike to distract his enemies. Before unification and the Edo period of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan had fallen into myriad civil wars and violent conflicts. Various warlords used the unruly conditions to lay siege on Kyoto, from where many believed they could control all of Japan. Although peace existed between the daimyo around Kyoto—Shingen, Oda Nobunaga, and Tokugawa Ieyasu—Ieyasu and Nobunaga aligned against Shingen, a formidable opponent. Shingen took his leadership philosophy and banner design from the Chinese military strategist Sun Tsu, who wrote that leaders should be “swift as the wind, silent as the forest, ravaging as fire, immovable as the mountain.” Shingen’s nickname was “the mountain” after this passage. Though a brilliant strategistf, Shingen died in 1573, and historical accounts vary as to the cause. His army was eventually overcome during the Battle of Nagashino of 1575, where the opposition, armed with some 3,000 muskets, a symbol of the new era, wiped out his army in wave after wave. By 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu would assume the title of Shogun and launch 250 years of stability in Japan.

Kurosawa and Ide’s script invents a scenario based on Shingen’s reported use of a “shadow warrior,” or kagemusha, suggesting that the central thief, who resembles Shingen, served as the daimyo for two years in secret. The narrative finds Shingen struck by a sniper’s bullet outside an enemy castle. Weakened, he instructs his advisors on whether they should attempt to overtake Kyoto: “If something should happen to me, do not pursue that dream.” He advises them to hold steady, like a mountain. When Shingen dies, his younger brother, Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki), installs the thief to maintain the illusion that Shingen is alive, though the other warlords—Oda Nobunaga (Daisuke Ryū), Uesugi Kenshin (Eiichi Kanakubo), and Tokugawa Ieyasu (Masayuki Yui)—have their doubts. Only a few top advisors, personal attendants, and pages know the truth of the thief’s identity, and he must train to overcome his “base” instincts and behave as Lord Shingen would. Although brash and uncouth, the thief soon convinces those closest to Shingen, including his grandson and mistresses, of his authenticity, earning a deep admiration for Shingen’s life and philosophy. Though, the lord’s impulsive son, Katsuyori (Ken’ichi Hagiwara), who was passed over yet hungers to control the Takeda clan, remains defiant over the ruse.

Kagemusha explores the theme of identity when the thief’s personhood becomes meaningless next to his role as Shingen. In the film’s first scene, the thief accuses the lord of behavior no more noble than his criminality, for which he faces crucifixion. Shingen admits he is ruthless, to the thief’s surprise: “I am as wicked as you believe. I am a scoundrel. I banished my father and killed my own son. I will do anything to rule over this land.” Shingen is proof that even someone as ruthless as he can conduct himself with nobility, and even those in noble positions can be cruel. In the thief’s performance as daimyo, he feels affection for Shingen’s grandson and adopts his worldviews. But no matter how many of his soldiers or enemy spies he convinces, the double, who remains unnamed, cannot deceive Shingen’s favorite horse, whom no one else but the real Lord Shingen can ride. In a state of overconfidence about his performance, the thief mounts the horse. The animal quickly bucks him off, and Shingen’s mistresses rush to check him for injuries. The ploy is exposed once they notice that the thief is missing Shingen’s scars. This particularly cynical detail is pure Kurosawa in its portrait of people who cannot see the illusion right in front of them, while a horse, simple as it is, knows immediately that the thief is not its master. At this discovery, the clan unceremoniously ejects the thief from the Takeda castle, and Katsuyori takes over as the resident lord.

Ever a humanist, Kurosawa sees the variations between people as arbitrary. The director often portrays humanity’s obsession with people’s differences as their downfall, thus questioning the nature of reality, perception, and appearances, and what they reveal about a person’s identity. For instance, the various perspectives in Rashomon concern the events surrounding a rape and murder, with each witness interpreting the incident differently, implying that humans are incapable of objective truth. In Seven Samurai, the hired ronin agree to protect what they believe are guileless farmers from a band of raiders, but the farmers prove far from bastions of innocence. The kidnapping thriller High and Low questions class hierarchies, suggesting that the only thing separating an executive and a kidnapper is a social construct. In Kagemusha, the thief’s tragedy is that he no longer distinguishes himself from Shingen. After the Takeda clan discards him, the thief remains invested in the clan’s fate. He follows them under Katsuyori, who has ordered his army to march and watches their defeat from afar. Katsuyori has broken Shingen’s mountain rule—“Do not move”—which has sustained the clan and helped the thief be victorious in a previous battle. The Takeda clan is wiped out before the thief’s eyes, and though he has been spared execution, he rushes headlong into the fray, fighting for a lost cause with the passion of a leader, only to be struck by a musket. In his final moments, he stumbles into the river to rescue the Shingen flag, but he falls to his death. Floating downriver, he ironically takes the shape of a crucified man. By dying in the manner he does, in a passionate display of clan devotion, the double proves to be just as much Shingen as the real man.

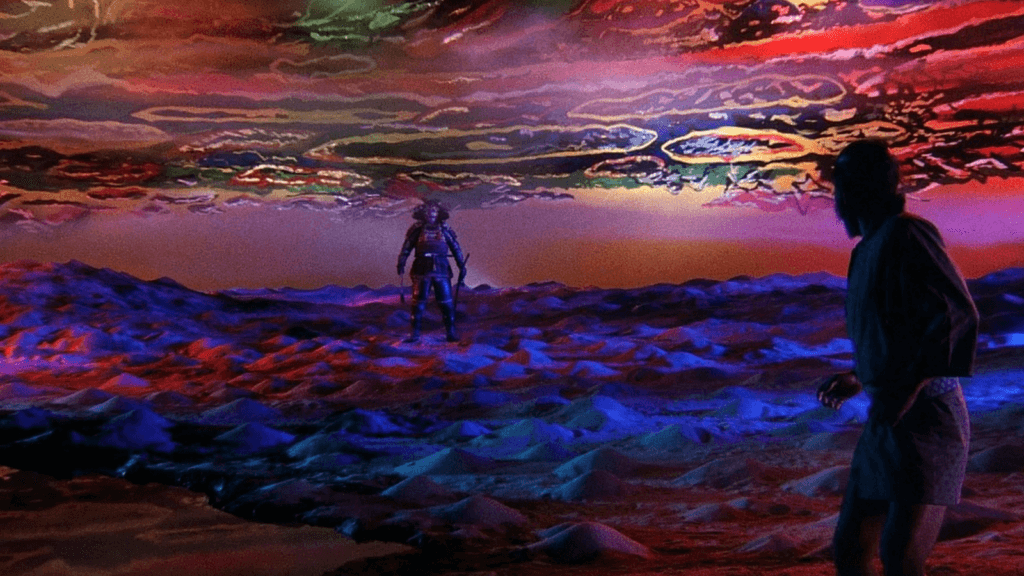

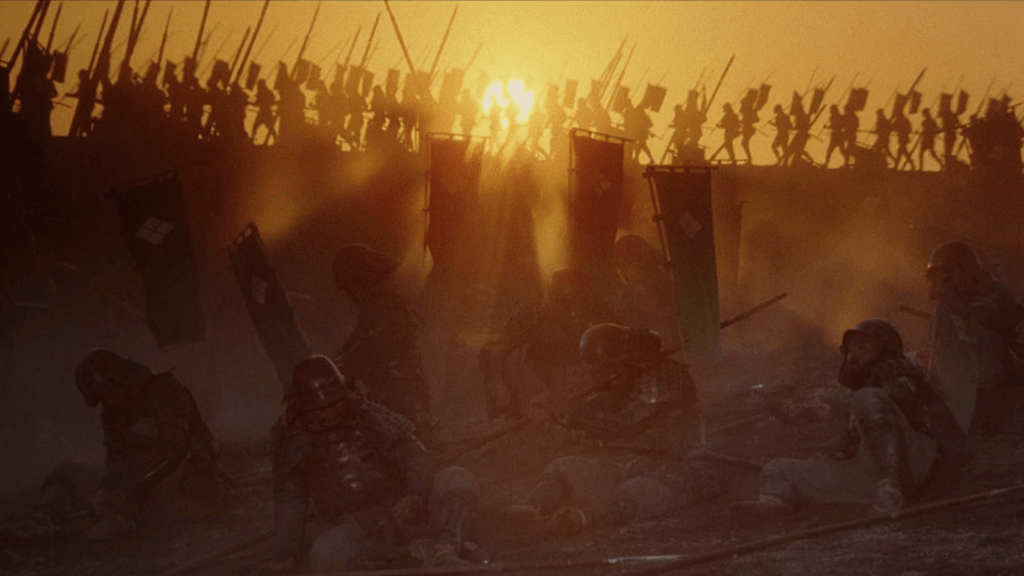

Kurosawa’s formal execution further highlights his investigation of reality and illusion. Whereas the director sought a measure of realism in his earlier historical epics, such as Seven Samurai, he embraces this reality-illusion dichotomy in Kagemusha. Abandoning historical detail apart from the scenario’s basis and authentic costumes, Kurosawa uses bold, expressive colors and dreamlike imagery. The production has more in common with Throne of Blood, the director’s take on Shakespeare’s Macbeth, than his more grounded efforts. Richie compares the film to the operas of Giuseppe Verdi, distinguished for their grandiosity and spectacle, as opposed to the naturalistic movement of verisimo operas. Kurosawa accomplishes this during a dazzling dream sequence, where the thief sees versions of himself in a boldly expressive landscape, recalling unearthly, stagelike sequences in Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) or even Singin’ in the Rain (1952). The look anticipates scenes from his 1990 feature, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, further suggesting the personal flourishes the director has added to Kagemusha. Similarly, battle sequences avoid realism with painterly red and blue skies, even a massive rainbow, while the finale, presented in an extended series of shots, conveys bloodied Takeda soldiers crawling, horses writhing on the ground, and corpses everywhere. The slow motion used in these shots, accented by composer Shin’ichirō Ikebe’s haunting and repetitive score, enhances the scene’s surreality.

Elsewhere, Kurosawa conveys a regality and theatricality through his mannered presentation, segmented into economic and intentional shots, without a single cut wasted. Watch the final battle sequence, in which Kurosawa assembles a distinct and repeated shot pattern, where Katsuyori orders waves of horsemen, lancers, and calvary men into the battlefield, and the opposition responds with a debilitating attack with muskets from behind a tree trunk fence. Kurosawa does not portray the action; instead, in a rigidly schematic execution, he shows only the response to what has occurred on the battlefield, instilling a sense of helplessness over the bloody reality of war. This choice emphasizes Kagemusha’s theme of shadows in that he draws attention not to the action but the result of that action, just as a shadow results from a tangible entity. The theme also applies to Katsuyori, who lives in his father’s shadow. Katsuyori and the thief feel Shingen’s “phantom” presence, though no literal ghost appears in the film outside of the thief’s nightmares. The phantom seems to possess the thief, whereas Katsuyori proceeds in defiance—a choice that leaves the entire Takeda clan obliterated. In effect, the phantom of Shingen has just as much substance as his physical counterpart, whereas the reality of Katsuyori amounts to little.

Richie calls Kagemusha a “hopeless picture” for its bleak finale and the notion that one will find little solace in reality. Many other Kurosawa scholars have deemed the picture one of Kurosawa’s lesser efforts, only exceptional as a comeback picture made by an aged director. But Kagemusha remains a passionate work that might be interpreted as Kurosawa’s renewed testament to filmmaking and art, suggesting that a powerful enough illusion can hold precedence over reality. When Shingen’s rival, Oda Nobunaga, sings upon learning of his death and the years-long presence of a double, he delivers a curiously tender moment that articulates this theme: “Life is but a dream, a vision, an illusion,” his voice rings out, a palpable melancholy behind it. If the narrative can be a crushing experience that leaves no character whole and the Takeda clan decimated, Kagemusha also believes in the power of representation and the potential for imitation to have real meaning. The thief’s assimilation into Shingen’s philosophy, his adoption of the role and emotional investment, and his ultimate willingness to die for his cause bring to mind Kurosawa, whose pitiable state found renewed meaning with this production and reminded the world of his mastery.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned by Mark and originally posted to Patreon on July 3, 2024. Thank you for your continued support and patronage, Mark!)

Bibliography:

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, 2002.

Goodwin, James. Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like An Autobiography. Knopf: distributed by Random House, 1982.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review