The Definitives

Jurassic Park

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Jurassic Park, Steven Spielberg’s marvelous visuals suspend his characters and, by extension, his audience in awe and revelation. Early in the film, a jeep transports skeptical scientists and experts to an ideal location within impresario John Hammond’s island theme park. A wide shot moves inward toward the spellbound faces of Dr. Alan Grant and Dr. Ian Malcolm, though Spielberg delays cutting to what has drawn their eyes. The director holds the shot, filling his audience with anticipation for whatever might evoke such a reaction. As the scene builds, Spielberg follows Grant, who removes his hat and stands up to get a better look. His mouth agape, Grant clumsily pulls his glasses off his face to reveal his bewildered eyes. The shot goes to Grant’s colleague and significant other, Dr. Ellie Sattler, who chatters on, mystified by a rare and extinct prehistoric plant she found on the island. Grant reaches back and turns her head to see what he sees, and her jaw drops mid-sentence. She, too, rises and removes her glasses, standing next to Grant in astonishment. The shot moves behind them, rising along with John Williams’ iconic score to greet a towering Brachiosaurus, a full-grown dinosaur whose long neck reaches to the treetops. The power of this scene resides in both the promise of something grandiose, captured in the actors’ expressions, and the fulfillment of that promise through outstanding movie magic: the convincing realization of a relic from Nature that now stands before our very eyes.

This scene in Jurassic Park marks a Spielbergian signature. The director has employed scenes like this throughout his body of work numerous times, where the character-spectator sees something overwhelming before the audience does, thus inviting our fascination. Spielberg pays the moment off by delivering an incredible sight that the audience sees through the spectator’s point of view. The tactic was used when Chief Brody first eyes the shark in Jaws (1975), when Roy and Jillian in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) finally see that Devils Tower is the monolith from their visions, when Elliot first sees the alien in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1981), and when Tom Cruise’s character can do nothing but watch the alien tripods erupt from under the city in War of the Worlds (2005). Elsewhere, Spielberg brings to life horrors that we could only imagine and perhaps never wanted to see, and yet we need to see because of their historical significance, so much so that we cannot look away: the gas chambers in Schindler’s List (1993); the D-Day invasion of Normandy beach in Saving Private Ryan (1998). In each case, Spielberg’s method creates a powerful desire to see whatever has ensnared his characters, and then he delivers an often breathtaking image to satisfy that desire. Spielberg is the pusher of our visual gaze. Not only does he implant the longing, if not desperate need to look upon something great, but he makes the act of looking a believable and, without exception, stunning experience. What could be more cinematic?

When Jurassic Park opened in the summer of 1993, Spielberg brought the childhood dreams of countless moviegoers to life by bringing dinosaurs back to the screen. What he achieved in his adaptation of Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel was an unparalleled realization of a natural presence whose only earthly reality could be seen in museum fossils. Films had tried for decades to deliver convincing dinosaurs to the screen. From The Lost World (1925) to The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), from Godzilla (1954) to The Land that Time Forgot (1975), filmmakers achieved B-movie dinosaurs using actors in foam suits and stop-motion animation. Though they evoked amazement in generations of older audiences and still contain a delightful sense of adventure and escape today, they could not live up to increasing demands for cinematic realism or the ever-diminishing suspension of disbelief in modern viewers. Spielberg himself said he was always more compelled by the giant lizards in King Kong (1932) than the titular ape, and so the director had his own expectations to meet. He embarked on a risky and uncertain venture to bring realistic dinosaurs to the screen, using not only Crichton’s well-researched scientific ideas to reinforce the plausibility of the plot, but new and untested cinematic technologies that could engineer the dreams of millions of moviegoers.

In its broad strokes, Jurassic Park is very much a monster movie, what Spielberg called “a helluva yarn.” Recklessly enthusiastic entrepreneur John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) prepares to debut an island theme park, featuring prehistoric creatures that will “drive kids out of their minds.” His scientists have bred dinosaurs using DNA from ancient mosquitos preserved in amber, but, of course, the resulting animals have proved dangerous. Nervous investors demand Hammond receive endorsements, and so Hammond calls upon three specialists—curmudgeonly paleontologist Alan Grant (Sam Neill), earthy paleobotanist Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), and unconventional Chaos Theory mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum)—to experience the titular park, provide an endorsement, and ensure his funding continues. Hammond flies the specialists to his private island west of Costa Rica and also invites his grandchildren, his “target audience,” including Lex (Ariana Richards) and Tim (Joseph Mazzello). As the scientists and their grandkids tour the park, the kids pose a challenge to the child-resistant Grant, whose companion, Ellie, wants children. Malcolm’s eccentricities test the entire group. Meanwhile, Hammond’s disgruntled programmer, Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight), executes a program that shuts off the park’s electricity so he can escape the island with dinosaur embryos to sell to Hammond’s competitor. Nedry’s plan goes south, and dinosaurs run wild all over the island, throwing humans and beasts together for the first time in 65 million years.

The film’s scenario and execution unfold by embracing a number of oft-used formulas, familiar yet renewed by both Spielberg’s expert direction and realistic, dino-centric plotting. Likewise, the story’s straightforward outline is a familiar concept for Crichton, already explored in the film Westworld (1973), which Crichton wrote and directed, about a malfunctioning Wild West theme park that wreaks havoc on its visitors. It also bears similarities to Crichton’s 1980 book Congo, where an expedition goes searching for treasure in an exotic jungle location and finds themselves victim to ancient, smarter-than-average animals. Like that story and many other Crichton texts, Jurassic Park also contains elements of a spy yarn, specifically corporate espionage, through the Nedry subplot, which involves stealing embryos genetically engineered by InGen for a shady competitor from Biosyn. These represent Crichton’s concerns more than Spielberg’s. “I was really just trying to make a good sequel to Jaws, on land,” the director said, having disliked the three Jaws sequels made by Univeral Pictures without his involvement. In her book about the director, critic Molly Haskell described Jurassic Park as “Jaws of the Jungle.”

Indeed, Jurassic Park bears similarities to Spielberg’s iconic shark thriller from 1975, often credited with launching the perception of summer as a blockbuster season. Both films concern powerful, frightening, man-eating creatures from Nature. Both place children in peril, with Jaws offering one boy who becomes fish food. Both feature a protagonist with a special, informed fear of their monster: Roy Scheider’s Chief Brody reads enough books on the subject to implant his terror of sharks; Grant is a world-renowned academic whose theories about Velociraptors suggest they’re as intelligent as they are deadly, problem-solving, pack-hunting predators. Both revolve around monsters that have instilled a lifelong fear in their director. And both feature a capitalist who willfully ignores demonstrated risks to human life in favor of profit. In Jaws, Murray Hamilton’s mayor refuses to close Amity Island beaches on the Fourth of July weekend, the biggest money-maker of the season, shark attacks notwithstanding. Hammond is a wealthier yet more genial counterpart to Hamilton’s mayor, but only slightly less deluded about the damage his choices have caused. “Next time, it’ll be flawless,” Hammon insists to Ellie, determined to make his island theme park work. “When we have control again—.” Ellie cuts him off. “You never had control! That’s the illusion.”

Hammond’s doomed attempt to control Nature to create a spectacle and rake in the profits leads to a central idea in Crichton’s book: Ian Malcolm’s counterargument, rooted in the Chaos Theory. One of Jurassic Park’s best sequences involves a discussion over lunch, where Malcolm and others confront Hammond’s false sense of control, calling out the irresponsibility of Hammond’s work with geneticists in bringing dinosaurs back to life. “Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen,” Malcolm observes. “But you wield it like a kid that’s found his dad’s gun.” Crichton sought to acknowledge that Nature could not be so easiy subject to predictable patterns or human control. His book’s consideration of Chaos Theory acknowledges the seeming randomness of the universe but insists that patterns exist beneath the surface—such as Jurassic Park’s geneticists breeding all-female dinosaurs, only to see them reproduce because they filled gaps in the preserved dino-DNA with genetic material from frogs. But Grant points out a pattern among some frogs the geneticists missed; they sometimes change gender from male to female to ensure the survival of the species. Malcolm warns Hammon that “life finds a way,” and it does. Crichton may have been referring to cloning experiments conducted in the early 1990s. However, with contemporary debates about genetically modified foods, CRISPR babies, dwindling seed diversity, artificial intelligence, and weapons development, Malcolm’s most iconic line still resonates: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

Spielberg recognized himself in Hammond. Perhaps to avoid an unflattering association, he reworked the character, making Hammond more sympathetic. Crichton’s book portrayed the character as an inflated carnival huckster and unrepentant capitalist. Spielberg softens Hammond into a good-natured, grandfatherly visionary, complete with the director’s brand of childlike wonder and determination to bring entertainment to the masses. Even so, Spielberg does not allow Hammond to escape unscathed. Malcolm questions not only the science but also the morality of Hammond’s willingness to commit crimes against Nature in the name of profit. “You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could,” says Malcolm. “And before you even knew what you had, you patented it, and packaged it, and slapped it on a plastic lunchbox, and you’re selling it, you wanna sell it.” In an anticipatory touch of self-reflexivity, Spielberg created a cinematic theme park beyond the diegetic gift shop’s branded plushies and lunch boxes. Besides the vast promotional tie-ins and merchandising, Jurassic Park led to actual theme-park attractions at Universal Studios Orlando and Hollywood, where animatronic dinosaurs leap out at roller-coaster riders who exit through gift shops identical to those featured in the film. Spielberg engages in mild self-criticism through Hammond’s delusion and hubris, but not to the extent that the film villainizes Hammond or leaves any negative associations with its director.

Although it’s tempting to claim Spielberg’s identification with Hammond fuelled his interest in Jurassic Park, the real reason is much more apparent: dinosaurs. Long before Crichton’s novel was published, Spielberg, mesmerized by prehistoric animals, had his eye on the author’s dinosaur book; but then, so did half of Hollywood. Several studios began a bidding war over the unpublished property. 20th Century Fox had Gremlins (1984) helmer Joe Dante lined up, Columbia Pictures felt Richard Donner of Lethal Weapon (1987) fame should direct, and Warner Bros. wanted their Batman (1989) cash cow Tim Burton behind the camera. But Universal Studios had an advantage, as Crichton and Spielberg had already started collaborating on a medical television series that would eventually become ER (1994-2009). Universal won the bid, paying Crichton $1.5 million for the film rights to his novel, as well as an additional $500,000 to adapt his book into screenplay form. Meanwhile, Spielberg wrapped production on Hook (1991) and hoped to film Schindler’s List afterward; however, Universal refused to greenlight Spielberg’s Holocaust drama unless the director made Jurassic Park first. He agreed, and the deal was struck.

After Hook‘s screenwriter Malia Scotch Marmo gave Crichton’s first draft of the script an inadequate rewrite, Spielberg hired David Koepp, then the little-known screenwriter of Bad Influence (1990), to rework the material. Koepp injected his standard fast-paced plotting and cleverly nuanced character descriptions, which would later become his signature in many Hollywood blockbusters, including Mission: Impossible (1996) and War of the Worlds. The writer also simplified exposition by following Spielberg’s cue to explain complex genetic processes with a ride that doubles as a cinematic cartoon. After all, what better way for Spielberg’s on-screen counterpart, Hammond, to communicate than by placing his audiences in movie theater seats and giving them a show? Koepp also altered characterizations and removed scenes for pacing and budgetary reasons, many of which were later incorporated into the sequels. In all, without Koepp, the finished film would have been a much different experience. After completing principal photography, Spielberg flew to Europe to begin shooting Schindler’s List during the day, while contributing to Jurassic Park’s post-production remotely at night. The emotional toll of his Holocaust drama left the director drained, and Jurassic Park provided an antidote by offering an entertaining diversion (along with regular calls from Robin Williams, who brightened the director’s mood with comic monologues).

Spielberg’s greatest technical challenge in Jurassic Park was bringing the dinosaurs to life. If the dinosaurs looked unconvincing, his entire film wouldn’t have worked. “I just opened the toolbox and took out every tool there was,” said Spielberg of his approach. To create the film’s dinosaurs, he consulted every kind of special effects artist he could find. First, he spoke with Bob Gurr, the designer of the Universal Studios theme park’s “King Kong Encounter” ride. However, he ultimately chose Stan Winston’s special effects company, then renowned for its innovative designs and practical solutions in James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) and John McTiernan’s Predator (1987). Winston and his team would create the life-size, tactile animatronics for the Tyrannosaurus rex, Velociraptors, Dilophosaurus, and sick Triceratops—all using lifelike skins and molds. Though Spielberg consulted stop-motion maestro Phil Tippett to create go-motion dinosaurs for scenes requiring faster movement, the result left the director unconvinced. He wanted his audience to believe the dinosaurs were real. Spielberg knew precisely how he wanted the dinosaurs to look; he just couldn’t find a way to achieve it. Then, Dennis Muren of Industrial Light & Magic suggested computer-generated imagery (CGI), which, until this point, had not yet delivered photo-realistic effects.

Spielberg and Tippett watched ILM’s first animated demonstration of the scene in which the T-rex chases a flock of Gallimimus, and both were amazed. “You’re out of a job,” Spielberg said to Tippet. “Don’t you mean extinct?” replied Tippet. The moment even made its way into the film, when Malcolm quips to Grant about the futility of paleontology in the face of living specimens. To this day, it remains ironic that one of the first major forays into CGI characters remains one of the most convincing, despite decades passing and many sequels arriving since the release of Jurassic Park. VFX artists have since had ample opportunity to improve CGI technology. And yet—along with sound designer Gary Rydstrom’s Oscar-winning work on the dinosaur voices, which utilize an unimaginable array of animal sounds—the film’s dinosaurs never fail to convince us of their reality. Every curve of their skin, every shadow, and every reflection is accounted for, requiring little suspension of disbelief. In fact, Jurassic Park received some mild disapprovals because many critics felt the dinosaurs outshined the humans. How could they not? Human beings have dreamed of seeing dinosaurs in the flesh since scientists first began to assess fossils in the 19th century, and Spielberg’s team went to great lengths to reinvent the cinematic dinosaur to coincide with modern theories. Specifically, their relationship with and probable evolution into avian species, or correcting the T-rex’s upright pose to one parallel with the ground. Spielberg’s signature childlike wonder allows him to capture the sublimity of dinosaurs—their equal parts beauty and danger—while his visual genius channels it onto the screen. Perhaps this is why seeing dinosaurs in the flesh remains so essential to the Jurassic Park viewing experience.

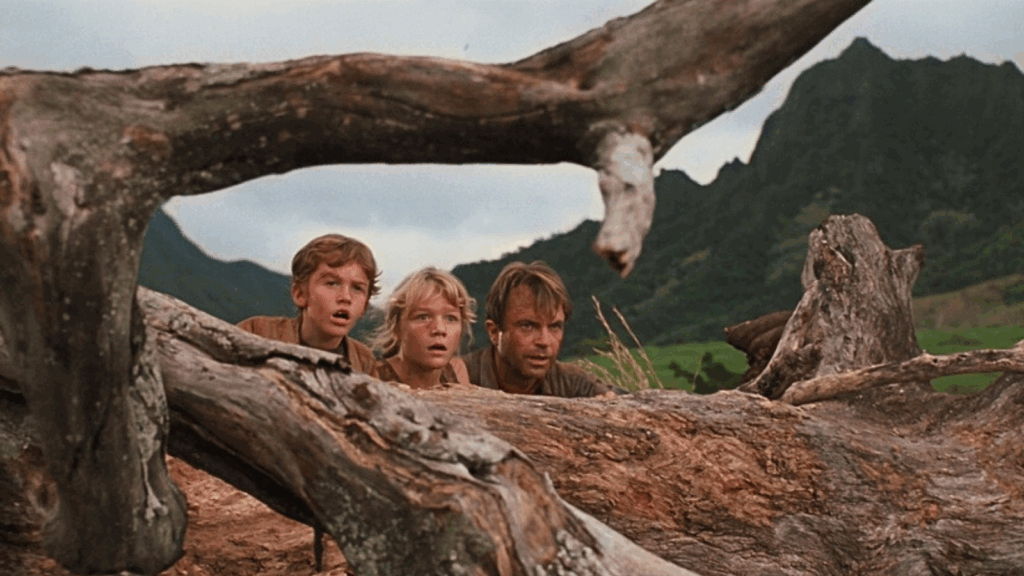

However, the dinosaurs also seem real in Jurassic Park because the actors sell their reactions so well. In a way, the film is about watching the actors react to what they see. Before nearly every dinosaur’s appearance, Spielberg shows us someone seeing the dinosaur first. We see their face light up with amazement or dread, and that expression feeds the viewer’s reaction when the film cuts to the animal. Before the group finds a sickly Triceratops, Grant’s calm inquisitiveness and Tim’s defiant curiosity prepare us not for a shock, but for an intimate encounter where we see a living, breathing, and tangible animal before us, so real looking in its animatronic state that no amount of scrutiny could convince us otherwise. In another sequence, Lex and Tim are left to feast in the visitor center after their horrifying jungle adventure. As Lex lifts a spoonful of Jell-O to her mouth, she freezes, and her hand trembles so much that we can hear her dessert smacking on the spoon. Then we see what she sees: Behind a painted screen of a Velociraptor, the silhouette of an actual Velociraptor lines up almost perfectly, snorting and sniffing. Tim, who has followed his sister’s stare to the silhouette, gasps in alarm. The film’s most famous scenes involve hearing the dinosaurs before they appear, as when a glass of water or puddle pulsates from the tremor of the T-rex’s heavy footsteps. Dinosaurs only consume a shockingly short 15 minutes of screen time, yet they have been burned into the moviegoers’ collective memory because the actors convince us that the dinosaurs are real. Had their performances and our belief in their fear of these beasts not been so convincing, our belief in the dinosaurs themselves would have been lessened, and the film not as effective.

But the subtleties of the human performances become just as interesting as the dinosaurs upon repeated viewings. And while few become as three-dimensional as Chief Brody in Jaws, they remain engaging with each revisitation. Goldblum’s turn as the talky, overconfident Malcolm echoes his performance in The Fly (1986) and thoroughly engages the viewer in his point of view—that what Hammond has done represents “the rape of the natural world”. The quietly warm scenes between Grant and Ellie endear us to them; the same is true of Grant’s protectiveness and jealousy when Malcolm inquires about Ellie’s availability and their relationship status. Even minor supporting characters shine thanks to excellent casting and memorable dialogue. Wayne Knight’s deplorable Dennis Nedry sets the plot into motion by shutting down the park’s power so he can escape with stolen embryos, marked by his taunting “hacker crap” on the computer system. Samuel L. Jackson’s engineer Arnold (“Hold onto your butts”), Martin Ferrero’s “bloodsucking lawyer” Generro, and Bob Peck’s park game warden Robert Muldoon (“Clever girl”) also shine in moments that have since become embedded into the collective cinematic memory.

Besides Hammond, Grant supplies another autobiographical touch from Spielberg. The character belongs to a long line of reluctant, irresponsible, or emotionally unavailable father figures in the director’s filmography—each an echo of Spielberg’s absent father. Grant’s antipathy to children did not originate in Crichton’s novel and emerged in the screenwriting process, suggesting that Spielberg helped develop Grant’s arc. But unlike many of Spielberg’s onscreen fathers, Grant’s aversion to kids and initial reluctance to start a family with Ellie seems to change by the finale. Jurassic Park shows groups of humans surviving together, just as Velociraptors hunt or Brachiosaurus graze in packs. These animals live and thrive in groups, not like lone wolves or solitary animals. Drawing from actual scientific studies, Grant’s paleontological theory—fringe at the time but since widely accepted—suggests that birds evolved from dinosaurs. Dinosaurs likely hunted in packs or flocks, he argues. And when Hammond first shows Grant, Ellie, and Malcolm dinosaurs, the sight confirms his theory. “Herds… they do move in herds,” he observes, tears welling up in his eyes. After surviving his ordeal in the park with Lex and Tim, Grant learns the value of family, of moving in herds. The alternative is Malcolm, an arrogant loner in tinted glasses and black leather garb who’s “always on the lookout for a future ex-Mrs. Malcolm.” Grant’s general dislike of Malcolm and parenting trial run with Lex and Tim, along with proof that dinosaurs, too, have families, reinforce the importance of family for the character. Spielberg acknowledges that families can be dysfunctional, yet his cinema consistently nurtures and reinforces family values.

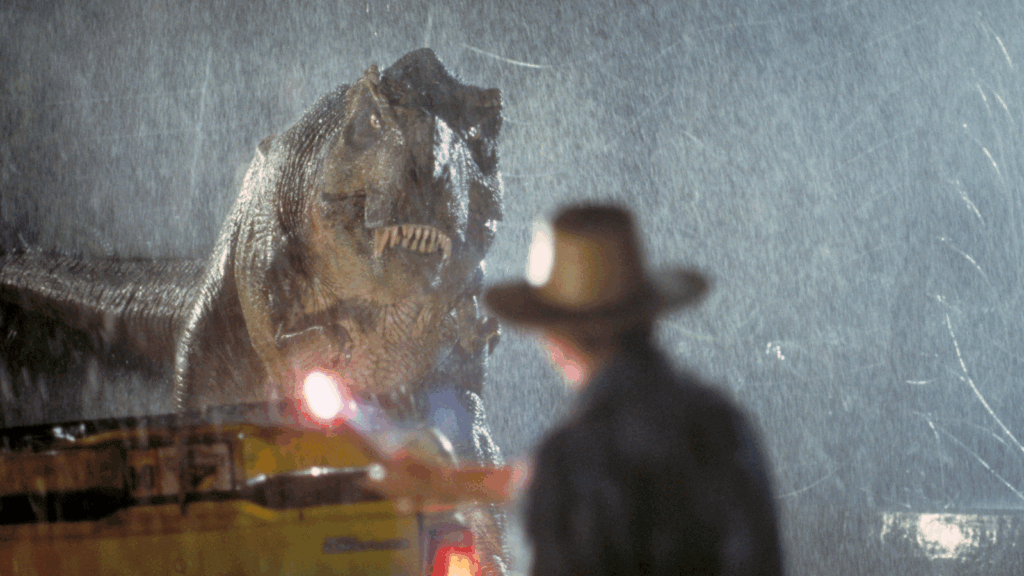

Even on a commercial project such as Jurassic Park, Spielberg’s fingerprints are undeniable. Although his output often goes overlooked in comparison to artistically minded auteurs, given his desire to appeal to mainstream audiences, the director’s persistent themes and masterful technical choices deserve celebration. Working with cinematographer Dean Cundey, whose collaborations with John Carpenter and Robert Zemeckis resulted in some of the best films of the 1980s, Spielberg delivers a work of staggering formal bravura. He moves his camera when another director would cut, developing elaborate, fluid shots that immerse the viewer in the action. But more significantly, he invents timeless imagery that has been sampled and replicated by other filmmakers in this franchise and others, and for good reason—Jurassic Park is crammed with one memorable sequence after another: the chilling opener that keeps the Velociraptors in the shadows; the first glimpse of the towering Brachiosaurus; the lunch debate in a dramatically lit room, shimmering with projected images of dinosaurs; the jaw-dropping arrival of the T-rex in the rain; the breathless escape from the treebound car that ends with a nod to Buster Keaton; the peaceful scene with a cowlike dinosaur who sneezes on Lex; Nedry’s death by the venomous Dilophosaurus; the escape from Velociraptors in the visitor center, revealing their frightening intelligence. Pushing the cinematic apparatus to its limit, Spielberg makes every sequence unforgettable.

For better or worse, Jurassic Park helped launch a new wave and style of digital filmmaking, where movie sets consist of vast blue or green rooms, and performers interact with visual cues that will be filled in by CGI during post-production. The actors of Jurassic Park were pioneers in this respect; their responsiveness to animals that are not there never fails to convince us of their fear or wonderment—watching Dern scream in terror as a T-rex approaches behind their speeding Jeep is enough to convince us of that. Audiences the world over believed in dinosaurs, too, when Spielberg’s film opened in June of 1993. Jurassic Park outperformed Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial to become the highest-grossing film of all time, earning over $400 million domestically and more than $1 billion worldwide —a record held until James Cameron’s Titanic opened in 1997. Other filmmakers such as George Lucas and Peter Jackson took the hint that integrating live-action with digital animation was the future of special effects, leading Lucas to pursue his Star Wars prequels and Jackson to develop films based on The Lord of the Rings and King Kong. Entire set pieces could be created on computers, and Hollywood saw the time savings and cost benefits of building cinematic worlds this way, often with mixed results. From one point of view, Jurassic Park‘s legacy resulted in an underwhelming insurgence of CGI creations, many of which cannot compare to Spielberg’s original theme park world, including the film’s sequels.

With Jurassic Park, Spielberg shows us the impossible and brings it to life with all the exhilaration of a theme park ride. The film operates like the initial grand climb on a rollercoaster, ascending toward that first moment when the Brachiosaurus looms overhead, gentle and graceful, and stands on its hind legs to reach a branch of leaves. The rollercoaster tips into a thrilling fall when the Tyrannosaurus rex chomps through its fence and investigates the tour group, like a bird pecking at its prey, and our hearts almost stop. The ride rails around unexpected corners when the Velociraptors hunt Hammond’s grandchildren and, to our horror, open doors and virtually speak to one another in shrill caws. Spielberg taps into our excitement by building upon it through his actors’ anticipant and fearsome faces, but also by channeling our lifelong fascination with these ancient animals, which can now only exist in our mind’s eye. More than his killer shark or various encounters with space aliens, Spielberg brings an incredible force of Nature to life in Jurassic Park, a film in which imagination and possibility merge. He reminds us that cinema can show us something we have always dreamed of seeing, and he makes us believe each visual wonder he conjures before our eyes. Truly, Spielberg is one of the great cinematic magicians, a virtuoso whose masterful manipulation of his audience and unparalleled execution imbue this film with an enduring timelessness.

(Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published on June 7, 2015. It was updated and expanded on July 2, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Buckland, Warren. Directed by Steven Spielberg: Poetics of the Contemporary Hollywood Blockbusters. Bloomsbury, 2006.

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Haskell, Molly. Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films. Yale University Press, 2017.

Kowalski, Dean A., editor. Steven Spielberg and Philosophy: We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Book. The University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). Faber and Faber, 2012.

Morris, Nigel, editor. A Companion to Steven Spielberg. Wiley Blackwell, 2017.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review