The Definitives

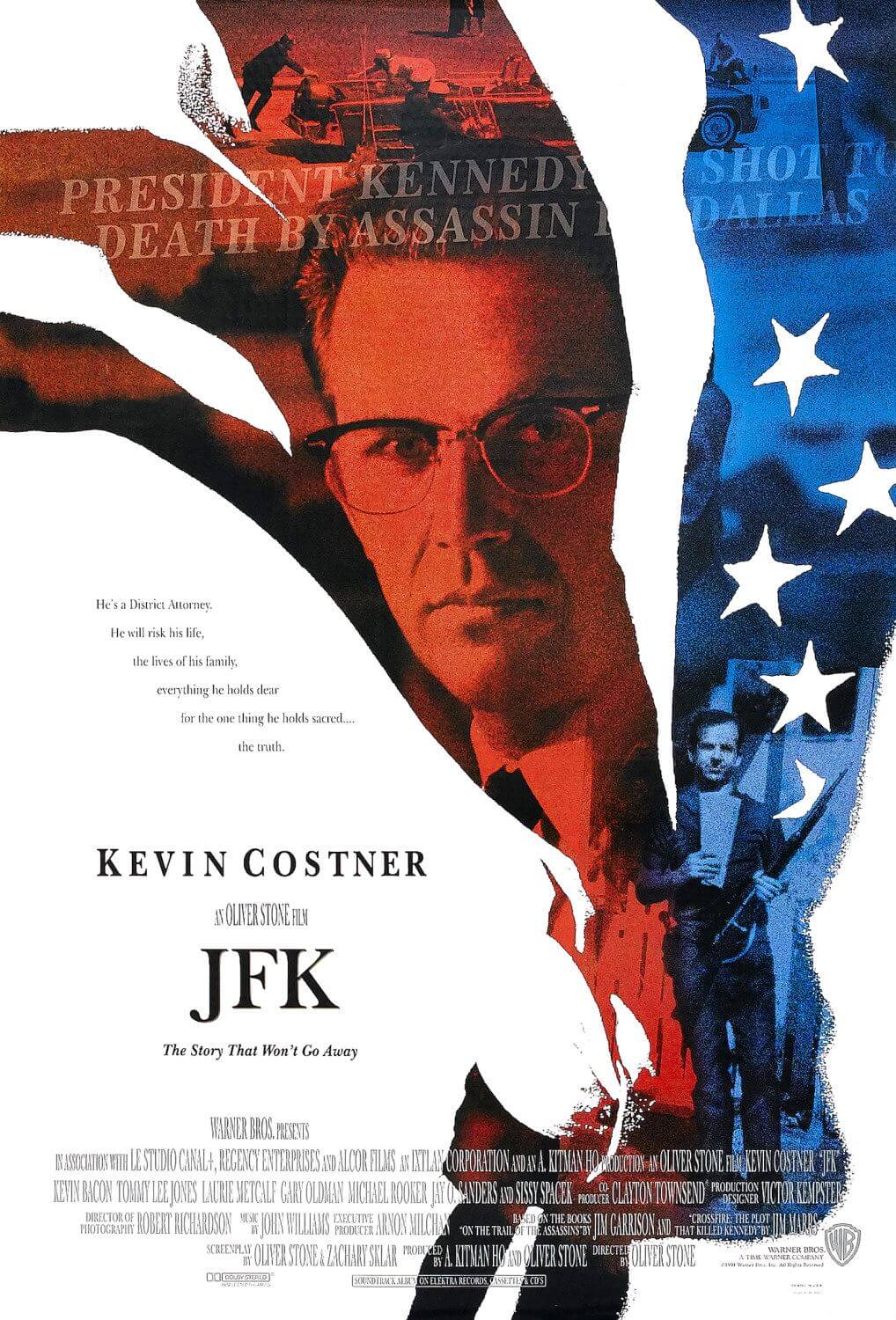

JFK (1991)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Just moments after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, the press and government officials assigned blame to a lone gunman. The popular theory: Lee Harvey Oswald, a bad man working alone, shot the young and handsome President with three bullets fired from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas. Shortly thereafter, Oswald was arrested, and then later killed by seemingly patriotic vigilante Jack Ruby. In the aftermath, Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren was tasked to investigate the assassination in 1964 and, along with seven committee members of the Warren Commission, concluded the assassination was the work of Oswald and Oswald alone. Meanwhile, Lyndon B. Johnson took over the country. Several years passed before the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations carried out the second investigation into the events. The HSCA stated, among many other conclusions that contradicted the Warren Commission report, that recorded police radio evidence proves at least two shooters fired that day, and there was probable cause to believe Kennedy’s assassination was a conspiracy. Throughout this period and beginning in 1966, District Attorney Jim Garrison of Orleans Parish, New Orleans, had his own ideas, and many of them are explored by Oliver Stone in his incredible film, JFK.

Hope for a factual and true account of the events surrounding Kennedy’s assassination remains improbable, if not impossible. Contradictory evidence and assessments have clashed since the Warren Commission report, including countless books and analyses written about the subject. Few other historical events have been debated so passionately by both the public and private spheres. By synthesizing these debates, Stone’s film takes considerable liberties with the facts and history surrounding the incident, using Garrison’s investigation as a lens through which his screenplay scrutinizes this watershed moment in American history, marking the loss of so-called “American Innocence”. JFK is not fact. Through bravura filmmaking, Stone fabricates a narrative out of truth, belief, and supposition. He breaks down a conspiracy so elaborate that anyone could get lost in its intricacies. He puts forth a singular filmic examination of the previous thirty years of theories, and in some cases exposes lies that were told surrounding Kennedy’s assassination. Where Stone’s 1993 picture remains a landmark is how it recapitulates varied assassination theories and commentary into a singular source, through which his audience can once again ask questions about what happened and why. And when those questions are inevitably given unsatisfactory or contradictory answers from official sources, Stone hopes we get angry and demand the truth.

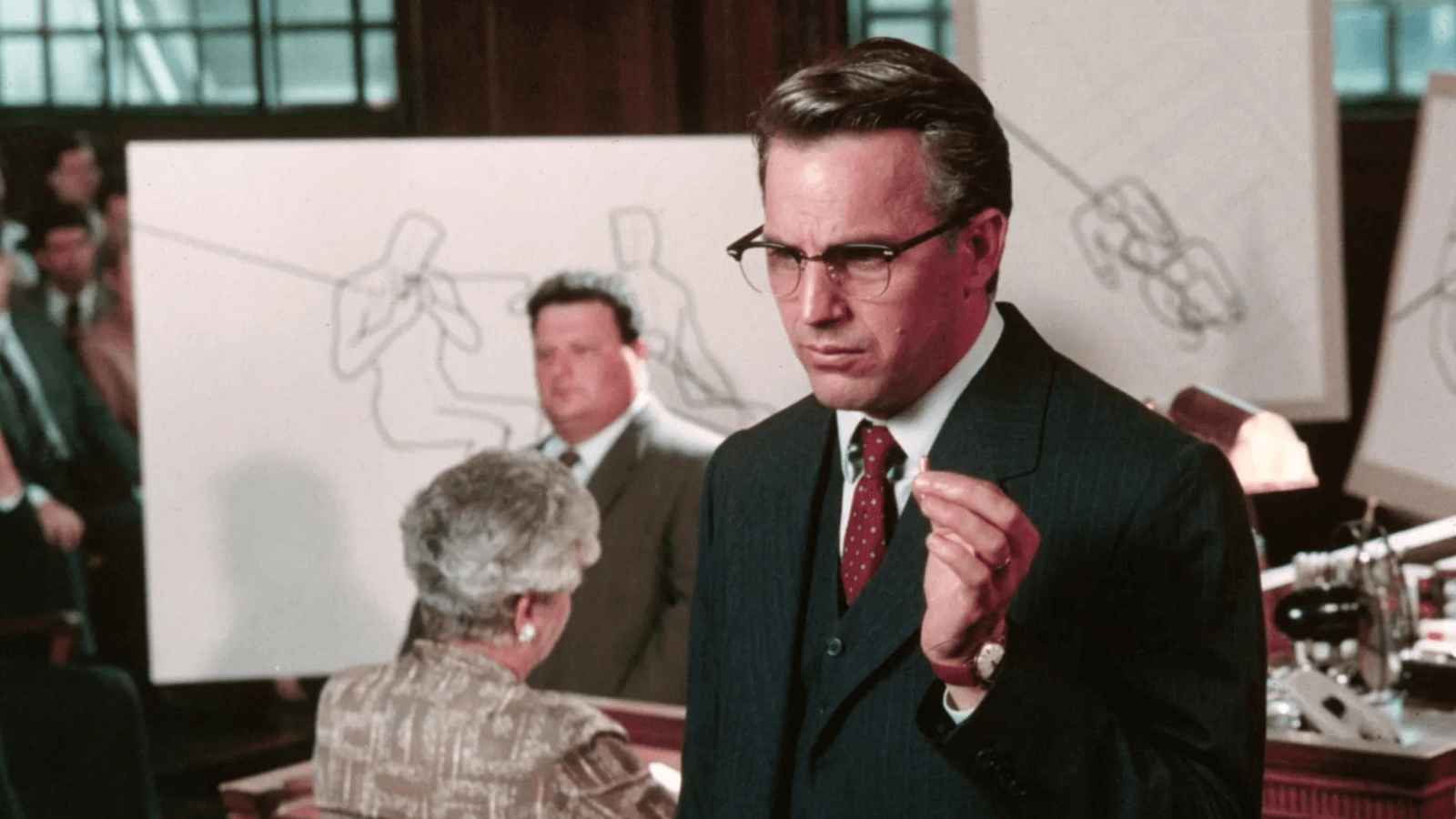

If JFK serves another purpose beyond fulfilling the needs of rousing, electric cinema, the picture creates an intense and undeniable metaphor for how American culture reacted to and feared the truth of the JFK assassination. Stone embeds enough facts into his fiction that the audience cannot help but question the official story and, in turn, realize the federal government’s claims about what happened were either incompetent or intentionally false. Stone once admitted, “No one really knows what exactly happened on November 22, 1963, or who did it, but there sure are an abundance of flaws in the official investigation.” Stone’s film sets out to challenge the Warren Commission by creating a blueprint of JFK conspiracy theories of merit and packaging those ideas in the form of a detective story unlike any other. The film’s goals are simple, but its details are byzantine. Several ongoing strains in JFK force us to question the official story: the film puts Oswald’s life under the microscope, suggesting he could not have been the lone gunman; it examines the details of the assassination in Dealey Plaza; it considers Garrison’s government informant Mr. X; it entertains notions that the CIA and mafia played roles in a conspiracy; and, in perhaps its most famous sequence, the film rebukes the so-called “magic-bullet theory” introduced by the Warren Commission. Primarily, Stone wants his audiences to believe that forces conspired to carry out a political coup d’état. He compared the notion to Hamlet, saying, “It’s the untold story of a murder that occurred at the dawn of our adulthood… The real king was killed, and a fake king was put on the throne.”

Stone’s choice and depiction of his protagonist only further complicate matters. He represents Jim Garrison as an American hero—the driving force behind the only criminal trial ever to stem from the assassination. Garrison maintained a most fervent hypothesis that supposed businessman Clay Shaw, a suspected CIA agent, somehow took part in a CIA plot to carry out a coup d’état against Kennedy. Garrison eventually brought Shaw to trial and lost. However, Garrison’s investigative methods and accusations that he used JFK’s assassination for media attention and professional gain have been washed over by the filmmaker in order to provide his film with a stalwart heroic figure to dramatize the proceedings. Stone makes a conscious choice to avoid many of the actual hardships and ugly truths in Garrison’s personal life, such as how Garrison’s investigation and his subsequent criticism lead to his personal ruin through alcohol and womanizing. What’s more, Garrison was not present at much of the trial because of a double hernia, leaving Assistant D.A. James Alcock to address the courtroom. Stone made these decisions as an artist assembling a drama with real-life significance, as opposed to a historical documentary or exposé. As a result, the director’s artistic choices surrounding Garrison are often the ammunition his film’s detractors use against the factual integrity of his coup d’état hypothesis.

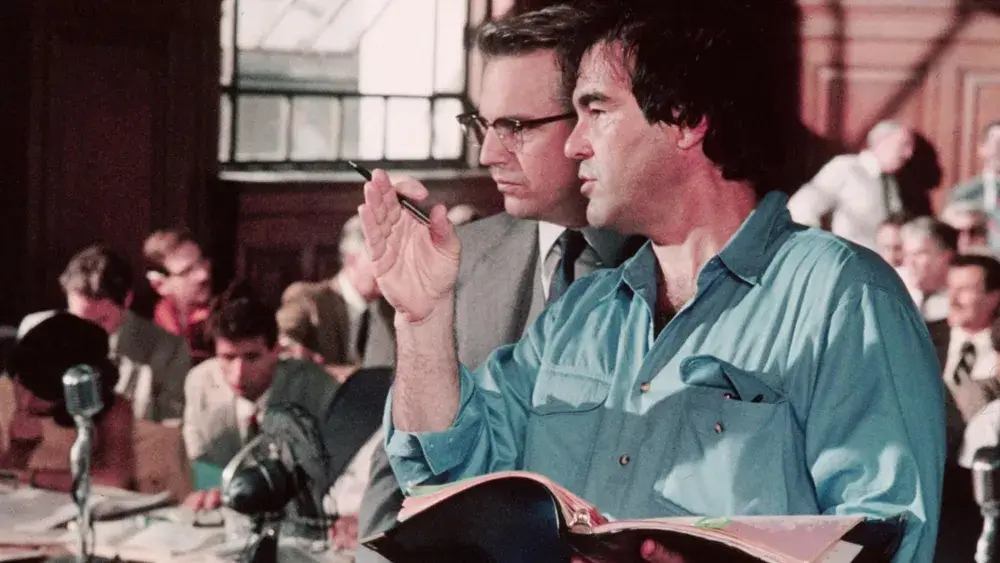

Indeed, Stone’s method of delivery contains expressive, if not sensationalist moments of cinematic flair. He’s unopposed to exaggerating for effect, using every device in his faculty to distribute a firm wallop to the viewer’s gut. The purpose behind his three-hour-and-twenty-six-minute (the Director’s Cut length) drama is to convince his audience, on an emotional level, that Kennedy was assassinated as part of a conspiracy. Stone sought to study the assassination through the eyes of multiple witnesses, though each perspective would be represented with conflicting details, like the characters in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950). Stone also culled influence from Costa-Gavras’ feverish thriller Z (1969), which depicts a political assassination early on and then, through the course of the film, reexamines what happened through eyewitness accounts and video footage. To achieve this approach, cinematographer Robert Richardson used multiple film stocks (35mm, 16mm, even Super 8) and aspect ratios, sometimes requiring several cameras with different stocks for a single scene, such as the film’s recreation of the assassination in Dealey Plaza. Editors Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia jump between these film stocks, creating JFK’s intense rhythm, the pace that makes over three hours of runtime feel like ninety minutes. The editors freely cut between real and recreated newsreel footage, black-and-white photography, overexposed flashbacks, and Richardson’s clean lensing on then-modern-day scenes. The entire film looks and feels like a triumph of montage (of JFK’s eight Academy Award nominations, it won for Best Cinematography and Best Editing).

Craft aside, development on JFK began in 1988 when Stone met Ellen Ray, a publisher for Sheridan Square Press, who had just published Garrison’s second book, On the Trail of the Assassins. She gave Stone a copy, and after reading it, he purchased the film rights. Garrison had many critics throughout the government, among historians, and even conspiracy theorists. But much of what Garrison wrote about—the extent of the alleged conspiracy—had extensive consequences in the American government. Regardless of Garrison’s oft-condemned methods or conclusions, for Stone the man epitomized his own passion to keep searching for the truth, no matter what. “I feel you have to keep digging into history to understand what happened to us and our generation,” Stone noted. He took the same approach to Garrison himself and, before he ever considered making a film based on Garrison’s book, he met a sixty-eight-year-old. Garrison had spent twenty-three years in the military, flew planes in World War II, was a former FBI agent, co-commanded his regional National Guard, and served three terms as a District Attorney. Stone’s mission: determine if Garrison had, in fact, used JFK’s assassination for media attention and professional gain or if he was a crusader whose aim was true, even if his methods were at times flawed. Ultimately, Stone determined Garrison’s preliminary investigation went out on a limb, and he trusted people he shouldn’t have; but after Garrison wrote a second book, he focused his theories more because he cared about the truth, not political gain.

Garrison was never intended to be the subject of JFK. Stone used Garrison’s case against Clay Shaw as a catalyst to expose the inconsistencies in the Warren Commission and further explore the wealth of theories surrounding the assassination. Stone realized that placing Garrison at the center of his film would earn criticisms from Garrison’s detractors, but the director felt exposing truths that had been mired in lies for thirty years was more important. After all, Garrison’s presence within the film was not biographical; the character was merely a metaphor who represented the work of several key investigations. In addition to Garrison’s book, Stone purchased the rights to Jim Marrs’ 1989 text Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy; he also hired a group of independent researchers who would assist in compiling theories. The filmmaker kept his efforts secret, as he was just finishing work on Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and would next shoot The Doors (1991). He learned filming Salvador and Platoon (both released in 1986) that, when shooting potentially controversial subject matter, the fewer people aware of his plans in the preliminary stages meant fewer obstructions once the production was moving forward. And once he had fully delved into the evidence available to his team, he became more convinced of an elaborate cover-up from positions of power within the U.S. government. “When you begin to sift through it,” he said, “there’s no escaping the thread.” Only after Warner Bros. became involved did Stone’s wife at the time stop worrying that he would end up dead, as so many key witnesses had, for poking his nose where it didn’t belong.

In spite of the contentious subject matter, Warner Bros.’ top brass embraced Stone’s idea, particularly chairman and CEO Terry Semel, who oversaw All the President’s Men (1976), The Parallax View (1974), and The Killing Fields (1984) during his time at the studio. After the production had a home and an estimated $20 million budget, Stone worked on the script with his primary collaborators: Yale graduate Jane Rusconi headed his research team; Columbia School of Journalism professor Zachary Sklar, who had served as editor on Garrison’s second book, served as co-writer. At times, Stone’s proclivities as a dramatist and seeker of historical truth were at odds. Stone used composite characters that would later earn him criticism among the press, who viewed JFK as a historical treatise instead of a motion picture. For example, there were two gay men who saw David Ferrie and Clay Shaw together, but Stone combined them into a single role played by Kevin Bacon. Stone also combined two essential meetings Garrison had in Washington D.C. into a single meeting with Mr. X, chillingly played by Donald Sutherland. The first of Garrison’s meetings was with Fletcher Prouty, a former Air Force colonel and Pentagon contact for the CIA; the second was Richard Case Nagell, an alleged CIA agent. Stone himself met with Prouty and incorporated much of what was said into the script. Regardless of his creative streamlining of the facts, Stone’s screenplay was becoming monumental and his budget was now double what he initially estimated.

Producer Arnon Milchan was there to smooth over studio roadblocks. Milchan sought out Stone and had to convince the director to allow him to produce. The producer was drawn to Quixotic projects such as Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982) and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), or later David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999) and Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014). Milchan is a maverick, much like Stone, and the producer’s appreciation of film as an art form meant he seeks to align with rare nonconformist filmmakers. Fortunately, he was the kind of producer who could convince Warner Bros. and European investors to double Stone’s originally quoted budget to $40 million. Milchan also persuaded the Dallas City Council to allow Stone to shoot in Dealey Plaza, which no one had ever done before. And he convinced the distributors to release an epic-length picture in theaters. Milchan also played a major role in the film’s casting, which included many of Hollywood’s most well-respected performers of the 1990s. Foremost was Kevin Costner as Jim Garrison, who beat out dozens of other actors who were considered (Harrison Ford, Robin Williams, Willem Dafoe, Tom Berenger, Alec Baldwin, and so on). When the director was getting closer to casting Costner, he wrote a note to himself saying, simply, “Kevin Costner—Jim Garrison, all-American quality.” Nevertheless, Costner originally turned down the role and required some coaxing. Stone heard a rumor that Costner promised his wife Cindy that he would take a year off after shooting Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), so the director sent Cindy a copy of Garrison’s books. She read them and, according to Costner, told him, “You have to do this.”

The production itself presented a challenge for Stone both physically and psychologically, since he was starting with a 156-page script. However, the script was actually longer, since pages were filled with notes, scribbles of dialogue, and arrows in the margins. While shooting, the director was methodical and detail-oriented, keeping track of the film’s multiple strains, including what wasn’t even in the script. Frequent cutaways to documentary footage or black-and-white video, and half a dozen other video processes, rattled around in Stone’s brain. “I thought I might really go down on this one,” Stone said. “This could be a movie that totally misses it. Too talky, too difficult, too much information… Maybe this will be Heaven’s Gate. But goddamnit, it’s worth it. Because this is one I believe in. No doubt.” Long before reading Garrison’s book, Stone’s life was shaped by the JFK assassination. He was at the formative age of seventeen in 1963, and what’s more, his parents were divorcing at the time. “It left me feeling that there was a mask on everything,” he once said. In subsequent years, Stone’s perception of his government continued to be shaped by “Vietnam, then the bombing of Cambodia and Laos, the Pentagon Papers, the Chile affair, Watergate, going up to the Iran-Contra in the eighties. We’ve had a series of major shocks.” These events shaped Stone and would deeply influence several of his projects, including Platoon, Wall Street (1987), Born on the Fourth of July, The Doors, and Nixon (1995). These films would provide a veritable catalog of his feelings during their respective periods. It almost goes without saying that JFK would become Stone’s passion project.

Perhaps due to the subject matter or simply Stone’s radical approach to all his films, most of mainstream Hollywood and the media was hoping the wildly ambitious, controversial film would overwhelm Stone and spin out of control, taking the director with him. Before shooting even began, George Lardner of The Washington Post arrived on-set uninvited, snooping around, and later published a 5,000-word reaction to his visit entitled “On the Set: Dallas in Wonderland: How Oliver Stone’s Version of the Kennedy Assassination Exploits the Edge of Paranoia.” Amid his censures, Lardner critiqued a stolen first draft of the JFK script as a series of “absurdities and palpable untruths” in what seemed like a preemptive smear campaign. Given Lardner’s history as a CIA investigator with contacts in the agency still, Stone began to feel like Garrison, as if forces in the government were trying to stop him. Likewise, Garrison had tried to subpoena various members of the CIA, governors, and crucial witnesses, but his requests were unreasonably denied. In the meantime, Garrison’s offices were bugged, his files copied and given to the defense, and attempts were made to bribe Garrison to stop his investigation. Similarly, various editorials in The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Time magazine picked apart Stone’s production and the early draft of his script, forming opinions about a film that had not yet been shot.

The screen story unfolds with Garrison’s investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald’s alleged friend David Ferrie (Joe Pesci), following a lead from witness Willie O’Keefe (Kevin Bacon), a convicted male prostitute, that Ferrie and Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones) had discussed killing Kennedy. At the same time, Garrison’s team investigates how the shooting from the Book Depository could not have been carried out for a number of reasons. They also investigate Oswald (played by Gary Oldman, but also by two other actors), a former Marine who defected to the Soviet Union, and yet suspiciously was able to return to U.S. soil during the Cold War without much hassle. As Garrison’s team learns more about Oswald, it seems he was indeed a “patsy” as he claimed to be, having become a low-level member of various anti-Castro Free Cuba Committee rallies, some held by former FBI agent-turned-private-investigator Guy Bannister (Ed Asner), as attested to by Bannister’s employee Jack Martin (Jack Lemmon). Or consider Jack Ruby (Brian Doyle-Murray), Oswald’s killer, who later called Kennedy’s assassination “an act of overthrowing the government.” These loose strains and leads discovered by the investigating team congeal into something more cohesive after Garrison meets with the so-called Mr. X (Sutherland), a colonel in the U.S. Air Force who suggests a vast governmental conspiracy conceived by the CIA and the U.S. military to maintain a thriving military industrial complex under Lyndon B. Johnson. Garrison finally takes aim at Shaw, hoping to shed light on the coup d’état conspiracy in open court. Though changing testimonies and dead witnesses weaken his arguments and he loses the case, he brings a new awareness to the facts by showing the footage shot by witness Abraham Zapruder for the first time in public, and detailing the absurdity of the Warren Commission’s “magic-bullet theory.”

When JFK was released on December 20, 1991, the polarized response from critics called Stone’s picture everything from “an insult to the intelligence” to “dubious” to “seditiously enthralling.” Discussions put Stone’s approach under the microscope for his blend of fact and tabloid-worthy fiction. Scenes of Clay Bertrand and David Ferrie donning costume attire—the former gilded to look like Mercury, the latter even more absurd-looking than his usual crooked wig and painted eyebrows—slapping and pinching each other’s nipples in the presence of the boyish male prostitutes hardly boasts credibility. Though the gay community recoiled at such scenes, moments like this show Stone at his frenzied best, using his hyperbolic style to wrangle his audience into hysterics over the official story. A few critics, such as Roger Ebert or Time magazine’s Richard Corliss, realized what Stone was trying to do. Corliss put it best: “Part history book, part comic book, the movie rushes toward judgment for three breathless hours, lassoing facts and factoids by the thousands, then bundling them together into an incendiary device that would frag any viewer’s complacency.” Elsewhere, MPAA president Jack Valenti compared JFK to Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda documentary, Triumph of the Will (1941). Likewise, an attorney for the Warren Commission, David Belin called the film “a big lie that would make Adolf Hitler proud.” To be sure, many missed the point entirely. Anthony Lewis of the New York Times described the film with incredulity, writing it “tells us that our government cannot be trusted to give an honest account of a Presidential assassination”—as if no government had ever betrayed the trust of its people before. By the time the dust settled around JFK, most agreed that, formally speaking, JFK was an amazement, but as history, it was nothing more than a three-hour conspiracy theory.

However, the term “conspiracy theory” comes with its own negative associations that, quite unjustly, dismiss all integrity of the associated claim as paranoia. Theories about the U.S. government faking the first moon landing or the Holocaust being an elaborate setup remain laughable examples embraced by crackpots. And yet, instances of relevant and accurate conspiracy theories exist throughout history, confirmed long after the fervor of their origination has passed. Accusations from the Martin Luther King Jr. camp that he was being monitored by the FBI may have sounded paranoid at the time, but J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO initiative speaks to the contrary: Hoover wanted “to pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them before they exercise their potential for violence.” This included feminist organizations, anti-Vietnam protesters, and civil rights movements. Elsewhere, those who consider The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to be far-fetched would find the CIA’s secret mind control experiments (codenamed MK-Ultra) alarming. Information on the Top Secret project was unveiled in 1977 when the Freedom of Information Act exposed the existence of the project, the details of which remain in question after CIA director Richard Helms destroyed many of the files on the program in 1973. Nevertheless, President Bill Clinton gave a speech in 1995 on a Bioethics Report that detailed the CIA’s mind control experiments conducted at U.S. hospitals, universities, and military facilities during the Cold War. (It should be noted that the former CIA director Helms later admitted Clay Shaw was indeed in the CIA, an admission that can only moderately validate Garrison’s in-court claims so many years after the fact.)

The point is, a conspiracy theory should not be disregarded simply because of its association by name with other, more fantastic conspiracy theories. Nor should JFK be disregarded as a work of pure fiction. Even looking at a few details within the film that happen to be accurate, unanswerable questions arise that contradict the Warren Commission and any lone gunman theory. Some would argue that any measure of fiction implanted into fact results in a work of fiction, but the degree to which JFK is fact or fiction is ultimately up to the viewer. Of course, not every detail in the film is clean and untarnished. But there’s a lot of truth in JFK, leading to a log of questions. The lingering questions Stone raises: “Why didn’t Oswald shoot when Kennedy was coming straight at him instead of waiting for a worse shot from the rear through a tree? What was Oswald’s history? How come he knew these people in New Orleans [Bannister, Ferrie, Shaw, etc.]? What about Ruby’s history? Oswald’s connections to Cuba? Ferrie’s connections to Oswald? Oswald’s military history, which seems to border on intelligence work? What about all the dead witnesses?” The answers to these questions, and the implications of those answers, are almost too big to contemplate.

JFK gets swept up in these questions and brings the viewer along for the journey. Some of these questions lead nowhere and cannot be supported by facts. Consider the scene where Pesci’s fervent David Ferrie raves to Garrison and his team in a hotel room about his involvement with Oswald and the CIA, plainly under the influence of multiple substances. “This is too fuckin’ big for you, you know that? Who did the president, who killed Kennedy? Fuck man! It’s a mystery! It’s a mystery wrapped in a riddle inside an enigma! The fuckin’ shooters don’t even know!” But his guard is down, and in his ravings, he confesses to helping carry out Kennedy’s assassination. Garrison’s own books admit that Ferrie never made such an outright admission, even though Garrison believed Ferrie and Oswald were indeed associates. Though the scene never occurred in real life, it illustrates for the viewer the level of unbridled paranoia Garrison saw in his witnesses, and the general feeling of suspicion and terror in the wake of the assassination. For every erroneous fact in JFK, there’s a measure of undeniable truth the film’s harshest critics are quick to overlook. Stone takes what Garrison believed and propels it into a drama, which in turn leads to an open discussion about the facts and suppositions of Kennedy’s assassination.

Along the way, Stone sets out to establish a number of facts, or truths. First, he establishes that Oswald did not act alone. He comes to this conclusion by forming a concrete argument against the Warren Commission’s belief that only three bullets were fired, largely using the Zapruder film combined with the topography of the bullet’s trajectory. Herein, we see with our own eyes how three bullets from behind could not have caused the damage inflicted on both Governor Connolly and Kennedy, whose head followed the trajectory of a bullet back and to the left, as though his shooter was in front of him to the right. Furthermore, Stone supposes that an organized assassination could not be pulled off by amateurs. There are less factual suppositions about the events leading up to the assassination and less tangible evidence, largely based on accusation and suspicion. But Stone suggests that the CIA found an enemy in Kennedy, who fired three major CIA players at the time (Charles Cabell, Richard Bissell, and Alan Dulles) and tried to restrict CIA paramilitary activities to the Pentagon, giving them the motive to conspire against their leader. Who else but the government could arrange for Kennedy’s Secret Service and military escorts to be so skeletal in Dallas? The facts after the assassination are also suspect, specifically in how LBJ ran the country. He did not follow Kennedy’s policies and instead aligned his policies with those of the Joint Chiefs, who clashed with Kennedy on virtually every major political issue of the time. Kennedy wanted to ban nuclear testing, end the Cold War, and avoid violent confrontations with Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam. And then there were the hours after the shooting when the press’ wire stories circulated around the globe in locations like New Zealand. The media was quickly provided with complete profiles on Oswald, despite there being utter chaos amid authorities in the aftermath of the shooting and no announcements made by those interviewing Oswald. This suggests a carefully prepared cover story.

Because Oswald had not yet been convicted or properly interviewed, the nation’s opinion on the subject was already set by the press, which pinned Oswald as the lone shooter—not the alleged shooter. History was already made for the media and the American people. No investigation needed. Those who still believe the lone gunman theory (a mere 30% of Americans, based on a 2013 Gallup poll) harbor an alarming disregard for the facts. But the reactions among many of those who believe there was some manner of conspiracy, governmental or otherwise, have an even more alarming response: apathy. Which is to say, the majority people (81% of Americans at its highest rate, according to the same Gallup poll) accept that Kennedy’s assassination was a conspiracy. Most accept this theory without anger or action. After all, Americans aren’t demanding the declassification of unreleased documents from the Warren Commission in any great number. How frightening and, to put it mildly, saddening, that Americans would believe in a conspiracy to assassinate their supposedly beloved President Kennedy, but then refuse to act in response or demand the truth. Regardless of how Americans feel about the false conclusions and their seemingly ingrained belief that a conspiracy did indeed take place, apathy takes over as history becomes almost mythologized into a distant bedtime story. Anger over the lies and the crime itself is subdued by the acceptance that we will probably never learn the truth about what happened. And once our anger is curbed to a mild grumble, whether it was a lone gunman or a conspiracy, the conclusion elicits the same defeated, unsatisfied response.

In many ways, Stone creates a Capra-esque story, a dreamy sort of tale set to John Williams’ classicized score, about a noble man who served in the Second World War and the Korean War, but he sees the assassination as the death of an idyll. A servant of his country, Garrison begins to investigate when he suspects something is amiss with the Kennedy assassination. The bulk of his investigation, conducted after 1966, leads him into dark territory, shattering his ideals and perceptions about his own country. And for seeking the truth, he is finally accused, disgraced, and beaten by the opposition. On these basic levels, the story of Stone’s version of Jim Garrison has an almost Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) quality that devolves with the hero’s disillusionment—recounting the death of American idealism. How appropriate that Stone wrote in his original casting notes for Garrison, “Find a real person—new Gary Cooper, create him yourself. A James Stewart, like old days.” Elsewhere, Stone was well aware that Garrison’s evidence was sometimes questionable, his conclusions broad, and his personal life troubled (as shown in squabbles with his wife, played by Sissy Spacek). On the job, he was accused of using truth serums, bribing witnesses, and making promises for reduced sentences. But throughout JFK, Stone transforms him into a metaphor for American idealism, depicting Garrison as an American hero so devoted to his cause that he occasionally overlooks his wife and child, while certain members of Garrison’s team (namely District Attorney Bill Broussard, played by Michael Rooker) refuse to believe the all-encompassing nature of his conspiracy theory. Costner, who had already played iconic (actual and otherwise) heroes like Elliot Ness, Ray Kinsella, Lt. John J. Dunbar, and Robin Hood, was perfectly suited for Stone’s intentions for the role.

As Garrison’s delusions about American innocence are crushed by the end of JFK, we see before us the end of idealism, the destruction of hope for America. The glory of Stone’s intensely subjective film is that it remains angry. “Sure, we are showing you our theories and saying that we believe them to be true,” Stone remarked, “but we clearly differentiate between fact and theory in the film.” Working in such theory, JFK reminds viewers, most successfully during the film’s analysis of the “magic-bullet theory,” that inconsistencies run rampant in the Warren Commission—and not only regarding Lee Harvey Oswald. Stone assigns varied measures of culpability to the Pentagon, the CIA, the FBI, and the soon-to-be-sworn-in President Johnson—all to maintain and grow the economic viability of the military industrial complex by continuing a prolonged conflict in Vietnam, largely in response to Kennedy’s determination to pull troops out of Vietnam, and not to invade Cuba. Today, as the U.S. continues to find convenient reasons to invade or police other countries for oil and other natural resources, the potential of an elaborate scheme to perform a coup seems not so unlikely. If indeed Kennedy wanted to put an end to Vietnam, the dollar value attached to such a proposition would be catastrophic. Only after a tragic amount of death, and a now-unfathomable degree of stateside civil unrest and protest, was the conflict finally put to an end by the U.S. in 1973—just in time to prevent the country from falling apart at the seams.

Not having answers has instituted new characteristics into the American consciousness that remain alive and well today, which are: apathy and the dismissal of healthy paranoia, and their combined toxicity. Consider how reactions to JFK focused on everything unverifiable but refused to deal with the reasonable doubtsfacts put forth by Stone’s film, perhaps because they represent an uncertainty. People despise uncertainty, and they will believe just about anything in place of it. The populace feels a sense of apathy because they have long since accepted they will never know what really happened behind Kennedy’s assassination. Such apathy is noxious, poisoning Americans with the defeatist notion that The Powers That Be are all-powerful, undoubtedly duplicitous in one way or another, and therefore “What am I supposed to do about it?—after all, it’s not as though the government is breaking down my door.” So as long as we can live our quiet lives in peace, what does history matter? And besides, most of the people associated with the original investigation are either dead or too aged to be considered reliable. But all hope is not lost. Answers may still come, someday. The JFK Act of 1992, instilled in large part as a response to Stone’s film, demands all government records pertaining to JFK’s assassination to be made public by October 2017. But there’s a caveat. The President at the time, no doubt receiving briefings from the intelligence community, has the power to keep the records sealed.

Two statues welcome visitors to the National Archives building in Washington D.C., personifications of the Past and Future. The Past statue placard asks that you “Study the Past,” while the Future tells you “Past is Prologue.” Oliver Stone wants his audience to remember that, historically, the U.S. is not above carrying out an action that supplants one government for another. And so, JFK cannot be thought of as just a motion picture—though, what a fine motion picture it is on purely cinematic terms. Rather, it must also be regarded as an urgent and aggressive reflector of American culture’s distrust for its government, since most viewers walk away from the film believing, at the very least, that the lone gunman theory is either too simple or has been entirely fabricated to cover-up a coup d’état. Whether the viewer embraces one of the countless conspiracy theories or merely accepts that the Warren Commission remains negligent (or worse, a series of lies), the film taps into our subdued anger, reignites it, and asks that we demand to know what actually happened. There’s a moment at the end of Garrison’s closing arguments where Costner looks directly into the camera, seemingly breaking the fourth wall, and he says, “It’s up to you.” Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s quote from the opening of the film, also used in JFK marketing materials, comes to mind: “To sin by silence when we should protest makes cowards out of men.” JFK does not stand as a historical document or marker of fact; rather, with an incredible degree of formal audacity and skill, it compels us on an undeniable emotional level and asks that we continue to search for the truth.

Bibliography:

Hamburg, Eric. JFK, Nixon, Oliver Stone and Me: An Idealist’s Journey from Capitol Hill to Hollywood Hell. PublicAffairs, 2002.

Riordan, James. Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone. New York: Aurum Press, 1996.

Salewicz, Chris. Oliver Stone: Close Up: The Making of His Movies. Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1998.

Stone, Oliver. JFK: The Book of the Film. New York: Applause Books, 2000.

Toplin, Robert Brent. History by Hollywood “JFK: Fact, Fiction, and Supposition.” University of Illinois Press, 1996, pp. 45–78.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review