The Definitives

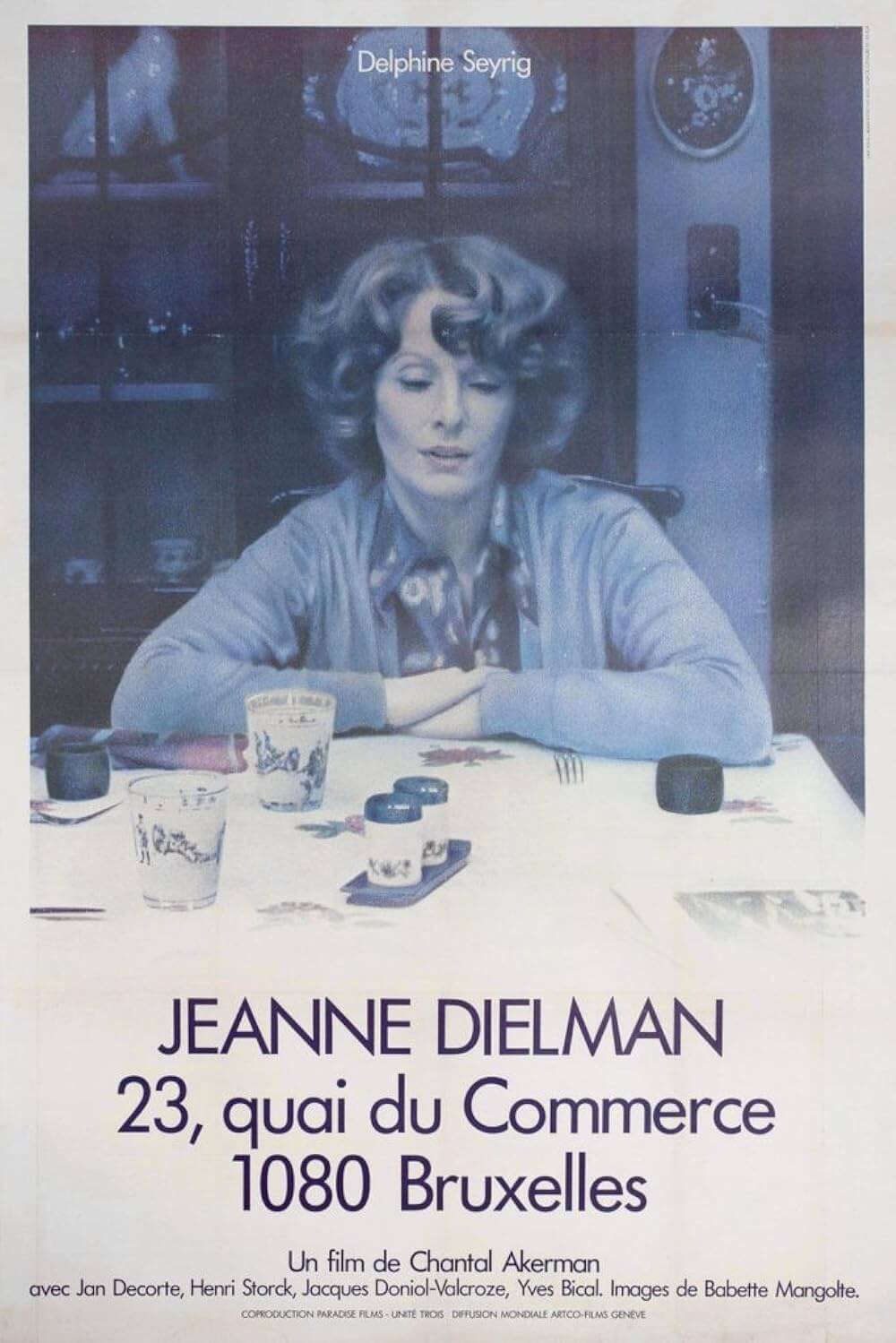

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles confronts the reality that, under the dominant patriarchal structure of most films, cinema rarely acknowledges the stagnation of a routinized homemaker. Akerman’s masterpiece, released in 1975, is an urgent alternative that considers the oppressive weight and anxiety of domestic spaces for its female protagonist. Delphine Seyrig plays Jeanne Dielman, a bourgeois widow who carries out a repetitive series of menial household chores. For nearly three-and-a-half hours, the viewer watches Jeanne in cinematographer Babette Mangolte’s straight, factual, static shots, devoid of close-ups or expressive movements. The fastidious mother busies herself in the kitchen, washes in the bathtub, dusts furniture, prepares meals, and searches far and wide to match a missing button from her son’s coat. But as G.W.F. Hegel wrote, “the familiar is not necessarily the known.” For extra money, Jeanne provides sexual services to a daily john, though the act is no more significant in her empty life than any other errand. These repetitive tasks keep Jeanne occupied and maintain her sanity, though Akerman, a radical and experimenter, also makes us a witness to the gradual degradation of her schematized life, a trap that has become a comfortable box. Within the crumbling pattern of Jeanne’s life, Akerman scrutinizes the relationship between performance and identity, exposing how the male gaze has framed women throughout the history of cinema, and in doing so, Jeanne Dielman offers a realistic substitute that refuses to categorize its central character into any of the narrow roles usually assigned to women in film.

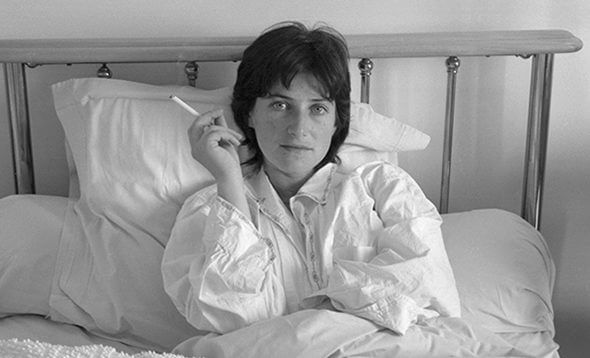

Born in Brussels in 1950, Akerman rebelled against her upbringing in the Belgian bourgeoisie. As early as fifteen, she was influenced by structural film and conceptual theory. She studied at the Belgian film school INSAS and, after the 1968 student riots in France, she studied filmmaking in Paris. But the film grammar taught in most film schools did not interest Akerman; she quickly abandoned her formal education to explore experimental filmmakers in New York, where she lived in the early 1970s. The work of avant-garde artists such as Michael Snow, Jonas Mekas, and Andy Warhol taught Akerman that filmmaking could be about more than making money; films could say something about how bodies occupy and ultimately reject time and space. She had already explored this idea in her debut short, Saute ma Ville (1968), a sort of prelude to Jeanne Dielman that features an 18-year-old Akerman enclosed in a kitchen setting, where she carries out domestic rituals with frenzied abandon before setting the space ablaze. With several more short films and documentaries, the young director used extended shots to inhabit a filmed subject in support of realism. By watching her subjects engage in banal tasks in her both documentary and fictional work, she observes everyday experiences such as eating, rearranging furniture, and having sex. But the way she watches disrupts the line between acting and prolonged descriptive scenes; she creates spaces that, after enough time, begin to escalate ideas.

Akerman was just 25 when she made Jeanne Dielman. It was the first film she made that follows a traditional narrative trajectory, though her approach can only be described as traditional compared to her earlier, more experimental work. When she conceived the film in 1973, it came from a rush of inspiration. She would show the routine gestures of a domestic woman, which are images that rarely occupy the cinema screen, and deny the viewer the typical visual schema associated with women on film, such as voyeuristic angles or editing that frames and reduces a woman’s experience: mothering, sex, madness, passivity, and a moral compass for a man’s life and actions. Akerman was intent on capturing the lifestyle she had escaped in Brussels, which she had witnessed in her mother. Her Jewish parents had fled Hitler’s Germany in Poland and settled into a middle-class existence, which Akerman observed growing up but never saw represented in films. Her resulting project details three days in Jeanne’s life and the mundane experiences that fill the character’s time, whether they be the efficiency with which she prepares wiener schnitzel—using the time in-between stages in the recipe to wipe down the countertop or clean dishes—or the meaningless, programmed conversations she has with her son, Sylvain (Jan Decorte). At the same time, Jean-Luc Godard was a major influence on Akerman; she cites Pierrot le Fou (1965) as the film that made her want to become a director. She based Jeanne on her mother, but it may be Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1966), in which housewives engage in prostitution to afford the latest and greatest household commodities, that influenced Akerman’s choice to show Jeanne turning a daily trick to make ends meet.

Akerman was just 25 when she made Jeanne Dielman. It was the first film she made that follows a traditional narrative trajectory, though her approach can only be described as traditional compared to her earlier, more experimental work. When she conceived the film in 1973, it came from a rush of inspiration. She would show the routine gestures of a domestic woman, which are images that rarely occupy the cinema screen, and deny the viewer the typical visual schema associated with women on film, such as voyeuristic angles or editing that frames and reduces a woman’s experience: mothering, sex, madness, passivity, and a moral compass for a man’s life and actions. Akerman was intent on capturing the lifestyle she had escaped in Brussels, which she had witnessed in her mother. Her Jewish parents had fled Hitler’s Germany in Poland and settled into a middle-class existence, which Akerman observed growing up but never saw represented in films. Her resulting project details three days in Jeanne’s life and the mundane experiences that fill the character’s time, whether they be the efficiency with which she prepares wiener schnitzel—using the time in-between stages in the recipe to wipe down the countertop or clean dishes—or the meaningless, programmed conversations she has with her son, Sylvain (Jan Decorte). At the same time, Jean-Luc Godard was a major influence on Akerman; she cites Pierrot le Fou (1965) as the film that made her want to become a director. She based Jeanne on her mother, but it may be Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1966), in which housewives engage in prostitution to afford the latest and greatest household commodities, that influenced Akerman’s choice to show Jeanne turning a daily trick to make ends meet.

In the first hour, Akerman establishes Jeanne’s routine on a Wednesday, observing with precise, unwavering detail as the protagonist follows every task on her mental checklist. Jeanne moves about her apartment’s few rooms, shuts lights off as she goes from one room to another, prepares meals in the kitchen, penny-pinches by saving flour for the next meal, babysits a neighbor’s infant, lays down a fresh towel on the bed for the day’s john, and hides her compensation in a tureen. Each of these tasks is shown in real-time, with computative clarity, fixing her controlled pace and calmed procedure in the viewer’s mind. Wednesday’s routine creates an expectation for what will occur on Thursday and Friday, each day separated by intertitles, while also establishing the orderliness of her chores and how they should look on a typical day. Patricia Patterson and Manny Farber called Jeanne Dielman a “still-life film,” hinted at by the title that defines its character by her domestic space of 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. But the foundational schedule established on Wednesday begins to crack on the subsequent days. When variations and disruptions in Jeanne’s domestic rituals occur, the experience becomes anxiety-ridden and tense, as does the persistence of Akerman’s formal austerity. Jeanne has been cast into a role that demands control, a notion thrust upon her by a patriarchal culture that denies her an inner life. Her entire being is organized into precise actions and units of time, and she fears time that is not efficiently spent. When her chronic need for control is threatened, everything begins to unravel.

Jeanne Dielman is an encapsulation of second-wave feminism of the 1970s, which disentangled how women were subjects of patriarchal power, a socially and biologically synthesized rulebook that positions women at the bottom of a gendered hierarchy and often reduces them to domesticated figures. Although modern feminism has settled into a broader fourth-wave that more closely resembles humanism—questioning established systems of power that marginalize specific social, racial, economic, and sexual orientations through social exclusion—Akerman’s film is firmly established in an earlier period. In the 1960s, the Women’s Liberation movement began to organize and expand upon first-wave feminism’s concerns with suffrage. The second-wave raised questions about representation and gender roles, while it also acknowledged the roles of men as progenitors of a patriarchal system. Feminist film theorists and critics, authors such as Molly Haskell, Laura Mulvey, and Joan Mellen, began to question the traditional roles of women in cinema that were stereotypes and secondary to male characters—idealized as madonnas or demonized as whores. Akerman emerged as film feminists began to address issues of the pervasive male-centric authorship in filmmaking, whereas the rare historical women filmmakers such as Lois Weber, Alice Guy-Blanche, and Ida Lupino were considered exceptions to the rule of male auteurs. Obviously, the second-wavers did not solve these problems of representation or authorship in cinema, as these necessary conversations still occur today.

Nevertheless, since the earliest days of cinema, women have debated how to identify and establish a feminine aesthetic or women’s cinema that challenges or at least finds equality with the dominant male gaze. Even among feminist film theorists, this aesthetic has been singled out as a variant or deconstruction of the prevalent formal language to which most viewers are accustomed, as film images have been historically arranged for heterosexual males. The question of whether to challenge the hegemony of these historically dominant images remains at the center of feminist filmmaking of the 1970s. But creating images that acknowledge the subjectivity of women cannot exist without creating a tension between assimilated and radical representational styles. The inherent confrontation that occurs when images veer from a patriarchal order mirrors a similar outcome of the women’s movement of the 1970s, which sought to encourage equality and social subjectivity in life beyond artistic representation. The assertion of power in women’s filmmaking represents a natural shift, a difference in the modes and grammar of storytelling and aesthetics. Feminist filmmakers of the 1970s—Gillian Armstrong (My Brilliant Career, 1979), Barbara Loden (Wanda, 1970), Joan Micklin Silver (Hester Street, 1975), Agnès Varda (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, 1977), Claudia Weill (Girlfriends, 1978)—took bold steps to emphasize how their methods detracted from the established order, using unconventional techniques that were sometimes met with harsh criticism from traditionalists, while their films rarely bridged the gap between artistic and commercial audiences.

The question remains: Do women filmmakers adopt a pointedly male style to tell aesthetically accessible stories about women, as filmmakers such as Mimi Leder, Kathryn Bigelow, and Karyn Kusama have done? Or do they explore an alternative project, as Jane Campion, Claire Denis, and Andrea Arnold often do? It is an unresolvable tension that every female filmmaker must address. In many cases, as suggested, this is inextricably linked to a film’s commercial prospects. A feminist film that contains a strong female character, such as Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman from 2017, also conforms to the patriarchal method of looking, which fetishizes Gal Godot, who plays the titular DC Comics superhero, as a beautiful Amazonian protected by her character’s impossibly scant body armor. It inspires women in the audience so unaccustomed to seeing female superheroes, yet it also rewards traditional male voyeurism. That film made just over $800 million at the worldwide box-office, whereas women filmmakers who break from the conventional schemes of male spectatorship have been relegated to the arthouse. This is where Akerman thrived. Her films were made in Belgium, distributed in a few European countries, predominantly France, but rarely did they receive any theatrical distribution in the United States outside of college campuses or film center retrospectives. Is this because the vast majority of U.S. viewers have committed themselves to patriarchal methods of looking, or simply because challenging art films prove too demanding for our short attention spans? It’s likely both.

The question of whether to employ traditional aesthetics to tell stories about women seems to never have entered Akerman’s mind, which is to say, her cinema is unflinching. She was an iconoclast who invented an original, thoughtfully composed aesthetic to possess and represent her characters, committing fully to their subjectivity. In a 1977 interview with Camera Obscura, Akerman expressed the conceptual intentionality of her work on Jeanne Dielman: “I do think it’s a feminist film because I give space to things which were never, almost never shown in that way, like the daily gestures of a woman. They are the lowest hierarchy of film images.” Akerman inhabits the spaces of her character, while Hollywood films, and even many feminist films prior to Akerman’s arrival, tend to ignore those areas. “I think the real problem with women’s films usually has nothing to do with the content,” Akerman said in the same interview. “It’s that hardly any women really have confidence enough to carry through on their feelings. [Female filmmakers] forget to look for formal ways to express what they are and what they want, their own rhythms, their own way of looking at things… not just what it says but what is shown and how it’s shown.” With these ideas in mind, Jeanne Dielman shows Akerman in complete control of her film’s form and content, delivering a film whose every moment feels essential to its feminist outcomes, even though she did not consider herself a feminist filmmaker: “I’m not making women’s films,” she said in a 1979 interview. “I’m making Chantal Akerman’s films.”

In the same year Jeanne Dielman was released, the women’s movement circulated the “Womanifesto” during the 1975 New York conference of Feminists in the Media, which established filmmakers and videographers in a uniform struggle against oppression. The manifesto stated, “We do not accept the existing power structure and we are committed to changing it by the content and structure of our images.” Akerman follows this declaration, albeit indirectly as she did not attend this conference. Working with a predominantly female crew, Akerman fostered a single-camera shooting environment that presented Jeanne as “a foreigner in an all-male world—the film industry.” Rather than framing Jeanne into images more easily observed by a voyeur, Akerman confronts the viewer with the reality of her subjectivity. Mangolte shoots almost entirely from the center, from a symmetrical angle, so that we share Jeanne’s space. “I didn’t have any doubts about any of the shots. I was very sure of where to put the camera and when and why,” Akerman told Camera Obscura. “The framing was meant to respect the space, her, and her gestures within it.” To achieve this respect, Akerman avoids using other formal tricks that have no place in the film: close-ups, sharp editing, fluid camerawork, and reverse shots—devices typically used to cut away from or render visually expressive the everyday life of a woman. As Amy Taubin wrote in ArtForum, “because of the subjacent angle and the absence of close-ups, we never feel as if we have power over her or superior knowledge of [Jeanne’s] experience. Indeed, the film is structured as much around information to which we are denied access as it is around that which is easily observable.”

The amount of time the viewer spends uninterrupted and alone with Jeanne, sometimes in four- or seven-minute takes, shows its concern with defining a neatened and impassive woman in her environment, observing every detail of her routine, her movements arranged by the order of her daily rounds. Ivone Margulies notes in her essay “A Matter of Time” how Akerman learned from her frequent cinematographer Mangolte that “the shot duration changes the equation between the concrete and the abstract, between drama and descriptive detail.” The use of time-images, a term coined by theorist Gilles Deleuze to describe the use of a single, unbroken shot to convey time and space, allows the viewer to consider a diligent mother who must endure a life of domesticity, with a necessary sex business on the side, to support her son and tend to her flat. The sheer amount of time spent with her, both in terms of the film’s runtime and the use of individual time-images, reveal the filmmakers’ willingness to engage and reconsider a woman like Jeanne Dielman. Akerman told interviewer Marsha Kinder “to show that someone doing the dishes can also be used as art, this is positive.” Writing about the film, Deleuze notes that Akerman’s “novelty” is in how she captures “bodily attitude as the sign of states of body particular to the female character, whilst the men speak for society.” His remarks note a distinctly patriarchal film industry in which characters like Jeanne Dielman are rare, if not entirely overlooked and unacknowledged by filmmakers.

At the 1976 Women’s Event at the Edinburgh Film Festival, Claire Johnston published her essay “Women’s Cinema as Counter Cinema” in which she demanded that audiences question the limited functions for women in film that, through cultural learning, served to position women into subordinate roles. Johnston writes how male characters take an active role in their stories, acting as individuals, whereas women often have roles that exist in relation to the men onscreen: they are mothers, sisters, objects of desire, nagging wives, femme fatales, and sex objects. They are abstractions passed down through a historical tradition of representational tropes, serving in mere iconographic relation to men. Akerman’s film is feminist not because Jeanne is a powerful female character, which she is not, but because it captures the unseen gestures of a woman rarely shown on the screen. She is objectified, but not in the voyeuristic way in which a patriarchal cinema would fetishize or objectify such a character. Her objectification comes in the form of a domestic subject to be observed like a specimen. As suggested above, she almost disappears into the mise-en-scène, quite intentionally so. Akerman even dyed Seyrig’s hair to match the color of her apartment’s wooden doors and molding, and the character nearly becomes part of the scenery. But from the expansive hours the viewer spends with the closed-off Jeanne-object, we develop a deeper subjective understanding.

Delphine Seyrig tosses aside her seductive image—established in her many collaborations with Alain Resnais, Luis Buñuel, Jacques Demy, François Truffaut, and William Klein—to play Jeanne Dielman. She disappears into her character’s muted and internalized condition, offering an incredible performance that relies on subtle expressions and nonverbal communication. Akerman gave Seyrig a unique opportunity to inhabit a character through a full embodiment, though her dialogue is limited to banal exchanges with her son (“Did you wash your hands?”) and the few people she interacts with outside of her apartment. To know the character, the viewer must distinguish between the seen and unseen, as Akerman refuses to clarify her with voiceover, flashbacks, cutaways to other characters, or other typical expositional devices. But the signs of Jeanne’s identity are readily apparent in Seyrig’s physical performance, from the composed way she carries herself on Wednesday, to the gradual tension in her body language on Thursday and Friday as her routine becomes unsettled. “In the past I was always able to bring something to the part I was playing, something between the lines,” Seyrig told Marsha Kinder. “But now I feel I don’t have to hide behind a mask, I can be my own size. It changes acting into action, what it was meant to be.” Seyrig’s performance is at its best in small moments with no action at all, when Jeanne is left with the threatening presence of her own thoughts. There is a sequence where Jeanne sits in silence and solitude in a rare span of time that hasn’t been accounted for. The internal panic that Seyrig conveys in her shifting posture and small gestures as she ponders how this time should be spent is excruciating.

Delphine Seyrig tosses aside her seductive image—established in her many collaborations with Alain Resnais, Luis Buñuel, Jacques Demy, François Truffaut, and William Klein—to play Jeanne Dielman. She disappears into her character’s muted and internalized condition, offering an incredible performance that relies on subtle expressions and nonverbal communication. Akerman gave Seyrig a unique opportunity to inhabit a character through a full embodiment, though her dialogue is limited to banal exchanges with her son (“Did you wash your hands?”) and the few people she interacts with outside of her apartment. To know the character, the viewer must distinguish between the seen and unseen, as Akerman refuses to clarify her with voiceover, flashbacks, cutaways to other characters, or other typical expositional devices. But the signs of Jeanne’s identity are readily apparent in Seyrig’s physical performance, from the composed way she carries herself on Wednesday, to the gradual tension in her body language on Thursday and Friday as her routine becomes unsettled. “In the past I was always able to bring something to the part I was playing, something between the lines,” Seyrig told Marsha Kinder. “But now I feel I don’t have to hide behind a mask, I can be my own size. It changes acting into action, what it was meant to be.” Seyrig’s performance is at its best in small moments with no action at all, when Jeanne is left with the threatening presence of her own thoughts. There is a sequence where Jeanne sits in silence and solitude in a rare span of time that hasn’t been accounted for. The internal panic that Seyrig conveys in her shifting posture and small gestures as she ponders how this time should be spent is excruciating.

With Jeanne’s days separated by precisely allotted units of time, her routine spins out of control when she experiences something new with her paid sexual encounter on Thursday. Jeanne usually times her dispassionate bedroom experiences against the time it takes to boil potatoes for her son’s dinner, but something different has occurred in the off-screen coitus. Now her entire day is out of sync. She forgets to replace the cover on the tureen after her experience and doesn’t comb her hair back into its rigid style. She drops a fork in the kitchen; she makes a bad pot of coffee and tries, albeit unsuccessfully, to correct the mistake; she fails to greet her son at the door. Nor does the outside world cooperate. On Friday, the infant she watches continues to cry, as if the child recognizes that Jeanne’s world is falling apart. At the café where Jeanne stops for a daily respite, another woman is sitting in her usual spot, and the regular server is nowhere to be found. As disruptions in Jeanne’s routine grow in their frequency, Seyrig’s surface begins to reveal her character’s panicked state; her body language grows uneasy, and her breathing elevates. The anxiety becomes palpable through the actor’s tense microexpressions and distracted appearance, which deviate from Jeanne’s laboriously prescribed composure established earlier in the film. Akerman’s soundscape, rendered in Jeanne’s quiet presence on the screen and the timid noise of her domestic routine, suddenly becomes louder as the character falls apart. Her exhales are distinct, she shuts cabinets and door with audible force, and her steps seem quickened and loud.

She reaches a breaking point when her sexual encounter with her Friday customer culminates in her orgasm, the ultimate loss of control. Although Akerman passes over the previous two days’ sexual encounters with a sharp cut from daytime to nighttime, the camera’s repetition breaks on the third day and shows the sex. Jeanne disrobes and appears beneath the john, staring at the ceiling as both of them breathe heavily, while Jeanne’s eyes blink. Her hand moves reflexively, and she covers her face with a blanket when she climaxes. Afterward, Jeanne dresses and her customer lies on the bed. All at once, she reaches for scissors on the dresser and plunges them into his throat, a moment that seems impulsive and shocking yet necessary. In the film’s final scene, Jeanne sits at the dining room table in the dark, her hand spotted with blood. She closes her eyes, and a curious smile appears and disappears from her face. It seems to be an expression of relief. She falls back into a state of composure, though it remains uncertain if the murder has been a liberation or an unrecoverable loss of control. “A lot of women have unconscious contempt for their feelings,” Akerman acknowledged, suggesting that this violent act may be followed by ruinous guilt. For the first time in the film, Jeanne sits with her domestic space in shambles, a dead body in the other room. And yet, she appears calm, content even. What should the viewer make of these final few minutes of the film? Are they a victory or a defeat?

It is possible to read Jeanne’s domesticity as a patriarchal institutionalization, similar to what conditioned prisoners begin to feel over long periods of time, where their familiarity with the confines of the penitentiary become comforting. Certainly the anxiety Jeanne experiences as her domestic routine falls apart represents evidence of not only Akerman’s portrait of Jeanne as a typical woman imprisoned in a male-dominated world but also her psychological institutionalization in that world. If so, what will happen to Jeanne after the murder, after the film fades to black? Will her emergence from the confines of her domestic prison play out similar to another institutionalized prisoner from cinema—Brooks (James Whitmore) from The Shawshank Redemption (1994), who cannot adjust to post-prison life and thus resolves to commit suicide? Has she been shattered into catatonia? Will Jeanne’s personal uprising lead to further acts of violence and feminist revolt, setting her on the run from authorities in a plot resembling Thelma & Louise (1991)? Suffice it to say, Jeanne’s response to her murder is less significant than the act itself, which serves as a symbol of rebellion. Author Hilary Neroni, in her book The Violent Woman, argues that a woman’s violence in cinema is “revolutionary” in her antagonism to a patriarchal ideology: “Violence often appears to erupt when ideology fails, when the symbolic or narrative structure breaks down.” With Jeanne’s demarcated and reduced role in a patriarchal society dissolved, the murder is a glorious escape from her repressive homemaker routine and an emergence into personhood.

It is possible to read Jeanne’s domesticity as a patriarchal institutionalization, similar to what conditioned prisoners begin to feel over long periods of time, where their familiarity with the confines of the penitentiary become comforting. Certainly the anxiety Jeanne experiences as her domestic routine falls apart represents evidence of not only Akerman’s portrait of Jeanne as a typical woman imprisoned in a male-dominated world but also her psychological institutionalization in that world. If so, what will happen to Jeanne after the murder, after the film fades to black? Will her emergence from the confines of her domestic prison play out similar to another institutionalized prisoner from cinema—Brooks (James Whitmore) from The Shawshank Redemption (1994), who cannot adjust to post-prison life and thus resolves to commit suicide? Has she been shattered into catatonia? Will Jeanne’s personal uprising lead to further acts of violence and feminist revolt, setting her on the run from authorities in a plot resembling Thelma & Louise (1991)? Suffice it to say, Jeanne’s response to her murder is less significant than the act itself, which serves as a symbol of rebellion. Author Hilary Neroni, in her book The Violent Woman, argues that a woman’s violence in cinema is “revolutionary” in her antagonism to a patriarchal ideology: “Violence often appears to erupt when ideology fails, when the symbolic or narrative structure breaks down.” With Jeanne’s demarcated and reduced role in a patriarchal society dissolved, the murder is a glorious escape from her repressive homemaker routine and an emergence into personhood.

Akerman’s formal minimalism, her almost documentary commitment to representing the straightforward and banal existence of a domestic woman as she carries out her chores, leads to a subversive and visionary statement—earning the film’s enduring place in the history of feminist filmmaking. Akerman’s films outside of Jeanne Dielman remain somewhat obscure, regardless of the fact that she has been hailed as an essential voice in feminist cinema, albeit a reluctant one. This film reverberates above her others because it builds over time through an entrenched narrative and formal experience. Conventional films have not prepared us to watch and engage with a homemaker for extended passages, and so initially, Jeanne’s efforts seem curious and bafflingly simple. Before long, we settle into the experience and grow familiar with her cadence from the bedroom to the kitchen; they even become hypnotic and engrossing. It becomes easier to identify with Jeanne, to feel assured by repetition. And later we become upset by the breakdown of her timetable, which we now recognize as stifling. Eventually, Jeanne’s violence defies what the viewer expects from such a character, and when she murders, there is a sense of freedom and release from the tension of her routine. It is a violence that confronts our relationship with patriarchal films and the patterns of watching them, which have catered to masculine perspectives of women. The revelation of Akerman’s work is how she immerses the viewer in a conventional woman’s subjectivity, discipline, and repression, and then uses that same absorbed mise-en-scène to convey her emergence. It is a statement that identifies the prison of gendered roles for women, while also representing the relief of escaping them.

(NOTE: A special thanks to editors Brenda Harvieux and Julian DeBerry for your thoughtful feedback during the development of this essay.)

Bibliography:

De Lauretis, Teresa. “Rethinking Women’s Cinema: Aesthetics and Feminist Theory.” Film & Theory: An Anthology. Edited by Stam, Robert and Toby Miller. Blackwell Publishers, Inc., 2000, pp. 317-336.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Gwendolyn, Audrey, editor. Identity and Memory: The Films of Chantal Akerman. Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

Kinder, Marsha. “Reflections on ‘Jeanne Dielman.’” Film Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, 1977, pp. 2–8.

Margulies, Ivone. Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman’s Hyperrealist Everyday. Duke University Press, 1996.

—. “A Matter of Time: Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce,1080 Bruxelles.” 17 August 2009. The Criterion Collection. criterion.com/current/posts/1215-a-matter-of-time-jeanne-dielman-23-quai-du-commerce-1080-bruxelles. Accessed 17 August 2019.

Martin, Angela, and Chantal Akerman. “Chantal Akerman’s Films: A Dossier.” Feminist Review, no. 3, 1979, pp. 24–47.

Patterson, Patricia, and Manny Farber. “Kitchen Without Kitsch.” Film Comment, vol. 13, no. 6, 1977, pp. 47–50.

Taubin, Amy. “A Woman’s Medium.” 23 January 2009. Artforum. artforum.com/film/amy-taubin-on-chantal-akerman-s-jeanne-dielman-21913. Accessed 17 August 2019.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review