The Definitives

Jaws

Essay by Brian Eggert |

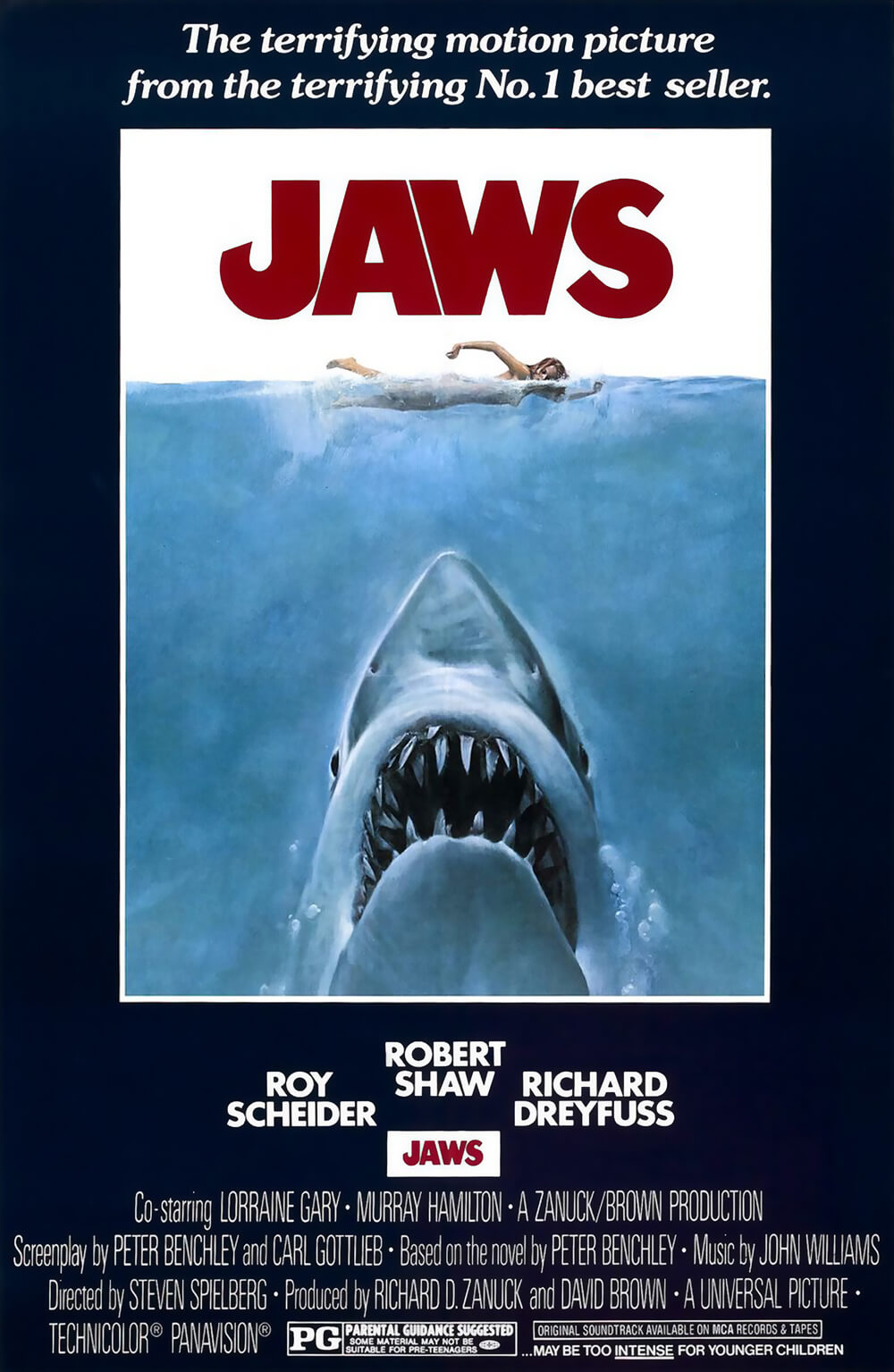

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a singular demonstration of cinematic suspense, and through its almost elemental construction, the picture is ideal blockbuster filmmaking. By mainlining directly into our most primal fears and needs as moviegoers, Spielberg communicates in broad storytelling tropes and vastly creative formal strategies, and in doing so his film is uniformly understood. In this, Jaws achieves a purity that has made it an essential classic. It is this same sense of purity that makes the machine-like monster, the Great White Shark, so devoid of human qualities or understanding, a primordial conflict against which any and all viewers can rally. In spite of and almost certainly because of the film’s famously troubled production, Spielberg stripped away all unnecessary components from Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel to find a direct access into our most basic emotional responses, and so demonstrated what would later be known as ‘The Spielberg Touch’—that uncanny way the director imbues his projects with an immediate classicism, magic, and universality that transcends demographic limitations and has since redefined the aims of Hollywood summer entertainment in both positive and negative extremes.

Widely written about and dissected by film historians and theorists, there is hardly a thing to be said or written about Jaws that hasn’t been done already, and yet we continue to return to this determining motion picture because it beckons us to. Whereas many great films contain a message or viewpoint that defines them as a product of their time or makes them stand out within their era, with Jaws it’s just the opposite. In making the film, the young Spielberg, then in his mid-twenties, had no particular motive except to make the best picture he could. It was someone else’s story, and he was tasked to bring it to the screen. It was a job. His goal was simply to be successful and deliver a film that would become a financial success. Later Spielberg would make films that were personal to him—like Close Encounters of the Third Kind or Schindler’s List—but Jaws is a product of his sheer, unmodified talent exercising itself under the extreme duress of a nightmare shoot. The experience was beyond exercise, actually, and more like an injection of steroids that resulted in a powerhouse blockbuster filmmaker.

In performing a raw display of artistic talent, Spielberg tells a story whose palate consists of primary colors: yellow beaches, blue water, and red blood. But the shark is the absence of color, as Robert Shaw’s obsessed shark hunter Quint describes it, “The thing about a shark, he’s got lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes. When he comes after you, he doesn’t seem to be living until he bites you, and those black eyes roll over white.” It is a basic creature swallowing up basically good characters. Look at the shark’s carefree and innocent early victims: a free-love bohemian girl, a dog, and a small boy. The story takes place over a 4th of July holiday week on New England’s Amity Island, disrupting not only everyone’s good time, but putting the very livelihood of the “friendship” island town (an amalgam of East Hampton, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket) at risk by halting the inflow of crucial summer dollars, much to the dismay of the selfish Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton). Ironically, though the 25-foot fish might represent Nature, it seems to be upsetting the natural order of things; in this respect, it’s less a conflict between Man vs. Nature and more about eliminating an almost inorganic beast that has interrupted the natural flow of Amity.

In performing a raw display of artistic talent, Spielberg tells a story whose palate consists of primary colors: yellow beaches, blue water, and red blood. But the shark is the absence of color, as Robert Shaw’s obsessed shark hunter Quint describes it, “The thing about a shark, he’s got lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes. When he comes after you, he doesn’t seem to be living until he bites you, and those black eyes roll over white.” It is a basic creature swallowing up basically good characters. Look at the shark’s carefree and innocent early victims: a free-love bohemian girl, a dog, and a small boy. The story takes place over a 4th of July holiday week on New England’s Amity Island, disrupting not only everyone’s good time, but putting the very livelihood of the “friendship” island town (an amalgam of East Hampton, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket) at risk by halting the inflow of crucial summer dollars, much to the dismay of the selfish Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton). Ironically, though the 25-foot fish might represent Nature, it seems to be upsetting the natural order of things; in this respect, it’s less a conflict between Man vs. Nature and more about eliminating an almost inorganic beast that has interrupted the natural flow of Amity.

Caught between local “islanders” in desperate need of a tourist season and the mounting threat that a Great White has staked a claim on Amity’s beaches, the outsider Brody (Roy Scheider), a former New York cop turned small town police chief, faces a strident opposition that demands to keep the beaches open, which he reluctantly agrees to do and immediately regrets. The shark’s danger is very real. Once several deaths imply this, it is confirmed by Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), an oceanographer who supplies the audience with scientific facts, Latin names, and scary truths about the creature: “What we are dealing with here is a perfect engine, an eating machine. It’s really a miracle of evolution. All this machine does is swim and eat and make little sharks.” And when the death toll rises and Amity’s citizens see the gargantuan size of the creature’s silhouette patrolling their waters, Vaughn finally realizes he should have listened to Brody and Hooper, and they hire their resident Ahab, hardened fisherman Quint, to hunt the monster down. Along with capable seaman Hooper and the drowning-phobic Brody, Quint sets out on his boat the Orca to find his White Whale. The second half of the film becomes a seafarer’s adventure of decent men hunting a leviathan; to be sure, the shark is hardly considered an animal of Nature within the context of the film, rather a cruel abomination that must be eliminated to restore balance.

The shark’s myth status becomes engrained in its basic form as an unrelenting and dehumanized killing machine. Without overt descriptions or personality traits to inform or allow specificity, the shark is a symbolic void onto which those who choose to project their meanings can and often do. Colorful and imaginative interpretations of Jaws have resulted. Many film theorists have posited the film was a conscious reaction to the Watergate scandal, with Mayor Vaughn so desperate to cover up the shark attacks on his “summer dollar” beaches that he’s willing to sacrifice a few swimmers for the higher priority of revenue. One of the screenwriters on the picture, Carl Gottlieb, has since argued that Spielberg was less interested in Watergate than Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People, wherein a lone doctor attempts to shut down a medicinal hot-springs, his town’s main tourist attraction, because they have been contaminated. This intentional evocation of Ibsen’s play allows for no end of interpretive parallels to events in the 1970s: Watergate, Vietnam, Kent State, and so on. More palpable viewpoints, such as Jaws being Spielberg’s update of Moby Dick, have been confirmed by the filmmaker himself.

The shark’s myth status becomes engrained in its basic form as an unrelenting and dehumanized killing machine. Without overt descriptions or personality traits to inform or allow specificity, the shark is a symbolic void onto which those who choose to project their meanings can and often do. Colorful and imaginative interpretations of Jaws have resulted. Many film theorists have posited the film was a conscious reaction to the Watergate scandal, with Mayor Vaughn so desperate to cover up the shark attacks on his “summer dollar” beaches that he’s willing to sacrifice a few swimmers for the higher priority of revenue. One of the screenwriters on the picture, Carl Gottlieb, has since argued that Spielberg was less interested in Watergate than Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People, wherein a lone doctor attempts to shut down a medicinal hot-springs, his town’s main tourist attraction, because they have been contaminated. This intentional evocation of Ibsen’s play allows for no end of interpretive parallels to events in the 1970s: Watergate, Vietnam, Kent State, and so on. More palpable viewpoints, such as Jaws being Spielberg’s update of Moby Dick, have been confirmed by the filmmaker himself.

And there are other readings. Take the persistent theory of the shark as a sexual predator and serial killer. In this, Spielberg places us in the shark’s perspective using underwater POV shots of bikini bodies and slender legs treading water. Not unlike the masked psychopath in the opening of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), the killer watches and follows its prey, and then attacks with prolonged jabs, as if to savor the moment. Likewise, in the first sequence of Jaws, a clear inspiration for Carpenter, our underwater killer does not devour the bohemian Chrissie (Susan Backlinie) in one quick chomp, but instead tortures her with agonizing bites to heighten her fear and its own enjoyment. The shark seems to derive much less pleasure when he kills his non-female victims, swallowing them up without delay. Then again, why must the shark be male? This is quite a presumption on everyone’s part; consider in its place that the shark is female and a grotesque realization of the vagina dentata myth, a pure castration machine. On a similar plane, another interpretation suggests the shark represents a colossal phallus that Brody, constantly emasculated in the film by the way his infectiveness to make a difference in New York has now carried over to the comparably sleepy town of Amity, must overcome to reclaim his manhood. A personal favorite reading argues how the shark represents bulimia, with the creature’s binging hunger counteracted by its own death drive in the finale to purge via explosion.

Amid these imaginative interpretations of the shark, a thing so ambiguous that it invites elucidation in any number of wild and well-argued designations, what becomes most important to recognize is that Spielberg was merely ‘on assignment’ during the production of Jaws. Producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown had worked with the then-26-year-old director on The Sugarland Express and thought of him for their adaptation of Benchley’s novel. Spielberg read the book and enjoyed it, but found many of Benchley’s subplots took away from the singularity of the human vs. shark conflict. Benchley wrote a first draft of the script, but Spielberg and his producers were left unsatisfied, and they approached several writers to complete additional drafts. Spielberg himself wrote a complete draft that went largely unused. Multiple other writers made smaller contributions, including John Millius and Howard Sackler, the latter having supplied Quint’s famous monologue about his experience with a shark feeding frenzy on the USS Indianapolis. Gottlieb, originally hired to bring some last-minute improvisation and humor to the actors, rewrote Benchley’s entire script, often the night before shooting. The famous technical challenges of shooting on open water and mounting delays left plenty of time for actors to rethink the script on-set, and much on-camera improvisation resulted (including Scheider’s legendary line, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”). Through these rewrites and ad-libs, Spielberg remained ever focused on completing his troubled production. In basic terms, the director had no particular subtextual message or social commentary to communicate; he just wanted to make a good movie.

Amid these imaginative interpretations of the shark, a thing so ambiguous that it invites elucidation in any number of wild and well-argued designations, what becomes most important to recognize is that Spielberg was merely ‘on assignment’ during the production of Jaws. Producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown had worked with the then-26-year-old director on The Sugarland Express and thought of him for their adaptation of Benchley’s novel. Spielberg read the book and enjoyed it, but found many of Benchley’s subplots took away from the singularity of the human vs. shark conflict. Benchley wrote a first draft of the script, but Spielberg and his producers were left unsatisfied, and they approached several writers to complete additional drafts. Spielberg himself wrote a complete draft that went largely unused. Multiple other writers made smaller contributions, including John Millius and Howard Sackler, the latter having supplied Quint’s famous monologue about his experience with a shark feeding frenzy on the USS Indianapolis. Gottlieb, originally hired to bring some last-minute improvisation and humor to the actors, rewrote Benchley’s entire script, often the night before shooting. The famous technical challenges of shooting on open water and mounting delays left plenty of time for actors to rethink the script on-set, and much on-camera improvisation resulted (including Scheider’s legendary line, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”). Through these rewrites and ad-libs, Spielberg remained ever focused on completing his troubled production. In basic terms, the director had no particular subtextual message or social commentary to communicate; he just wanted to make a good movie.

That alone proved challenging enough, as his production, far removed from the safety of a Hollywood water tank, filmed at Martha’s Vineyard against the unpredictability of the Atlantic Ocean. Waterlogged cameras, ever-present continuity concerns with shifting weather and passing boats, a malfunctioning rubber shark called “Bruce” (so-named after Spielberg’s lawyer), and general seasickness protracted the shoot from 55 days to nearly three times as many. The disasters are all documented with engaging detail in Gottlieb’s essential behind-the-scenes account, The Jaws Log, the determining production diary that makes any subsequent description of the film’s production superfluous. Of course, Spielberg has often commented that these disasters while filming were fortuitous, forcing his original vision to shift from a monster movie into a Hitchcockian chiller in which the shark is barely seen until the finale. It is the filmmaker’s skill, technical knowhow, and his ability to adapt to these ruinous conditions that finally made Jaws the accessible picture it would become. Had Spielberg unleashed a shark-heavy slasher where the creature is seen rather than implied, audiences may not have reacted with such equal levels of terror and pleasure. That Spielberg was forced to place us in the shark’s perspective allows our imaginations to foster the suspense which the film manipulates so well.

Throughout Jaws, Spielberg displays a master’s understanding of what makes movies and moviegoers tick. He understands that we see films like this because, to a degree, we enjoy being scared, and so he toys with our fear with a number of red herrings and false scares. Consider the scene where Brody pages through a book on sharks, looking at pages of shark attack victims, teeth, and bite radiuses in grisly detail. Behind him, we see his wife Ellen (Lorraine Gary) quietly enter the room and approach her husband. With Ellen inches away, Brody turns suddenly and they both jump, now laughing at how silly it was that they managed to frighten each other. And even though we saw Ellen coming, we jump too. In this, Spielberg acknowledges how Jaws is supposed to be fun, and yet unreal; like the pictures in Brody’s book, the film cannot get you. And then they set the book aside, as if to say “It’s just a movie.” We must continuously remind ourselves of this, as Spielberg continues to play with our expectancy and mounting fear. He injects several other false scares as the film goes on, many of them designed to distract us or diffuse our expectations for the actual scares to follow. Harry’s “some bad hat” looks like an approaching shark, as do the children with their false cardboard fin practical joke. Even Brody’s tension around the water implants an irrational unease about the ocean in view, inciting a common observation about Jaws that it “does for the ocean what Psycho did for the shower.”

Throughout Jaws, Spielberg displays a master’s understanding of what makes movies and moviegoers tick. He understands that we see films like this because, to a degree, we enjoy being scared, and so he toys with our fear with a number of red herrings and false scares. Consider the scene where Brody pages through a book on sharks, looking at pages of shark attack victims, teeth, and bite radiuses in grisly detail. Behind him, we see his wife Ellen (Lorraine Gary) quietly enter the room and approach her husband. With Ellen inches away, Brody turns suddenly and they both jump, now laughing at how silly it was that they managed to frighten each other. And even though we saw Ellen coming, we jump too. In this, Spielberg acknowledges how Jaws is supposed to be fun, and yet unreal; like the pictures in Brody’s book, the film cannot get you. And then they set the book aside, as if to say “It’s just a movie.” We must continuously remind ourselves of this, as Spielberg continues to play with our expectancy and mounting fear. He injects several other false scares as the film goes on, many of them designed to distract us or diffuse our expectations for the actual scares to follow. Harry’s “some bad hat” looks like an approaching shark, as do the children with their false cardboard fin practical joke. Even Brody’s tension around the water implants an irrational unease about the ocean in view, inciting a common observation about Jaws that it “does for the ocean what Psycho did for the shower.”

Indeed, Hitchcock defined cinematic suspense as an inconsequential conversation at a table. As the mundane conversation between characters proceeds, the filmmaker shows the audience a bomb under the table ticking down with five minutes to go on the counter. All at once, this routine conversation becomes unbearable for the audience as the participants jabber away without a clue. The opposite of such suspense would be a shock, where the audience is unaware of a bomb and suddenly it goes off. In Hitchcockian terms, Spielberg shows us the time bomb ticking under the table early on with Chrissie’s death, and as his picture proceeds, the ticking continues and slowly makes us writhe in our seats, until the film’s final hunt in the third act when the bomb seems to explode from the water onto the stern of Quint’s boat. Better even, Spielberg introduces the shark without showing us the shark. The director’s evident mastery of this approach, necessitated by his troubled production, allows for our imaginations to run wild. The famous opening employs those underwater POV shots and John Williams’ iconic two-note theme to establish the shark character; in subsequent scenes, the theme needs only to pulsate to instill our fear. Later, the appearance of a fin, the reaction of a witness, the presence of a tooth left behind, or the reappearance of the yellow barrels Quint has harpooned into the shark reinforce our terror without actually showing us the bomb’s wires and dynamite. When the shark finally does appear, our imaginations have filled in the blanks otherwise left gaping by the production’s prop shark, an awkward foam thing that caused countless hours of wasted fumbling on-set. Seeing behind-the-scenes photos and footage highlights what an effective filmmaker Spielberg must be to implant such terror from a shoddy assemblage of wire and neoprene and mechanical moving parts.

Just as our basic fears have been tapped, Spielberg touches basic emotions in his family dynamic, complete with his oft-used emotionally unavailable father figure, overlooked children, and the wife left to contend with the baggage. Much can and has been drawn from Spielberg’s subtly complex representation of Brody’s family, although the director sought to streamline their relationships from Benchley’s book, which, among other omitted complications, featured an affair between Ellen and Hooper. Instead, the family seems to have almost quiet acceptance of their mild discontent, with Ellen on the outside unable to reach her husband as he pours himself another drink after a long day. A most touching scene occurs at the dinner table the evening after the chief is publicly slapped by the mother of a boy who died. Feeling helpless and responsible, Brody sits before Ellen’s untouched dinner, as their son Sean plays shadow to his father’s labored, morose movements. Brody notes what Sean is up to and then plays along, and they both have a laugh. Then, he asks Sean for a kiss. Why? “Because I need it.” No further explanation needed. And in this simple gesture of affection, Brody and the family is somehow healed in the viewer’s eyes, even if Ellen still remarks on feeling disconnected from her husband. It is this rather simplistic perspective from Brody who, as paterfamilias, defines the film’s emotional pull and makes Jaws so accessible in its dramatic broad strokes. The power of the narrative drive takes care of the rest.

Just as our basic fears have been tapped, Spielberg touches basic emotions in his family dynamic, complete with his oft-used emotionally unavailable father figure, overlooked children, and the wife left to contend with the baggage. Much can and has been drawn from Spielberg’s subtly complex representation of Brody’s family, although the director sought to streamline their relationships from Benchley’s book, which, among other omitted complications, featured an affair between Ellen and Hooper. Instead, the family seems to have almost quiet acceptance of their mild discontent, with Ellen on the outside unable to reach her husband as he pours himself another drink after a long day. A most touching scene occurs at the dinner table the evening after the chief is publicly slapped by the mother of a boy who died. Feeling helpless and responsible, Brody sits before Ellen’s untouched dinner, as their son Sean plays shadow to his father’s labored, morose movements. Brody notes what Sean is up to and then plays along, and they both have a laugh. Then, he asks Sean for a kiss. Why? “Because I need it.” No further explanation needed. And in this simple gesture of affection, Brody and the family is somehow healed in the viewer’s eyes, even if Ellen still remarks on feeling disconnected from her husband. It is this rather simplistic perspective from Brody who, as paterfamilias, defines the film’s emotional pull and makes Jaws so accessible in its dramatic broad strokes. The power of the narrative drive takes care of the rest.

The only negative aspect about Jaws (aside from the unfortunate residual hatred it has spawned for sharks, which were hunted and viewed as monsters because of the film) is the way Hollywood reacted to its success as the film which defined summer as a blockbuster season. Major studios used to open their films soft, gradually distributing a picture to new markets as positive word-of-mouth spread. But Universal Studios marketed this film with aggressive television advertisements and a June opening that saturated all markets by opening in nearly 500 theaters. And though it was neither the first studio project to attempt this approach nor the first to break $100 million in receipts, the speed in which it achieved its box-office numbers was exceptional, and it eventually became the highest grossing film ever to that point. Studios took note, and suddenly Hollywood was in the blockbuster business. Only two years later, Star Wars broke the box-office record set by Jaws with a similar approach. Suddenly the young upstart and auteur filmmakers who dominated the height of sixties and seventies cinema—names like Martin Scorsese, Roman Polanski, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma, and William Friedkin—were once again at the mercy of studios who controlled the market by replicating the cultural phenomenon achieved by Jaws. Dollar signs sparkled in the eyes of studio executives, who discovered that aggressive marketing and a big budget could result in “critic proof” titles that, in spite of being another in a long line of high-tech hogwash, would turn the desired profit. Now our summers are nothing if not wastelands of forgettable wannabe phenomena, with only the occasional exception standing out among them.

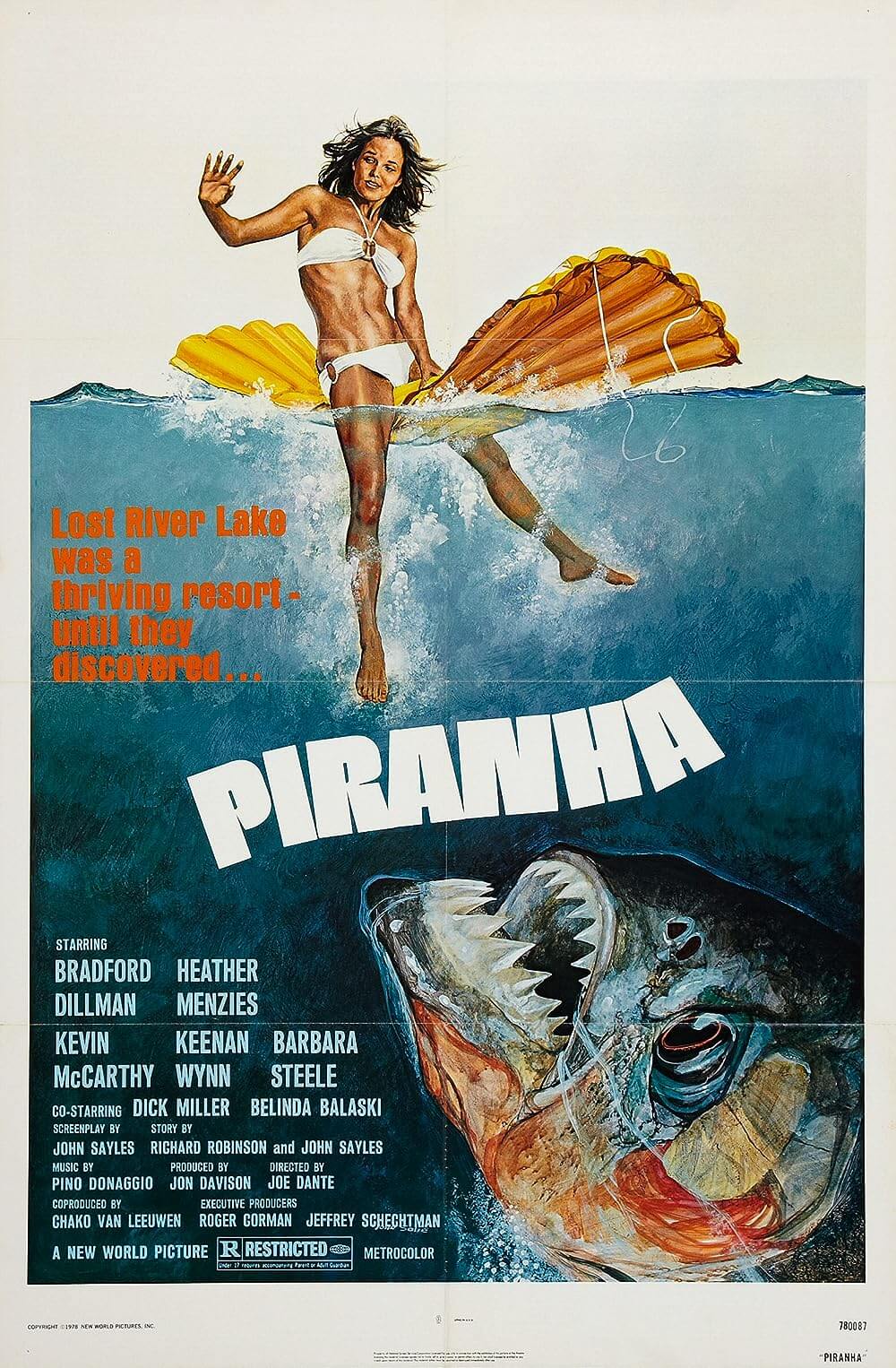

But forget for a moment that Jaws played a major role in an artistic downturn in cinema that may have resulted in the dumbification of U.S. audiences and the overt commercialization of films into elaborate marketing ploys. Forget the three increasingly forgettable-to-downright-terrible sequels that followed, and the only sometimes entertaining (see Piranha, 1978) offshoots. Reflect instead on what a carefully composed and genuinely great piece of filmmaking Steven Spielberg accomplished through unimaginable circumstances. Consider how every aspect of the film—the poster, the music, the thrills, the wry comic dialogue—is nothing short of iconic. Every scene shows a master at work to create something uniformly consumable and visually distinct, amounting to a purity assembled through an incredible technical and narrative artistry. How easy it is, perhaps due to the years of oversaturation, to take Jaws for granted! In its most basic understanding, it is a cherished picture of unrelenting suspense. But it remains such a readable, unlikely cognitive experience because there is so much to which we can assign meaning. Thus, Jaws will never lose its potency, no matter how many times one sees it. Along with Casablanca, Star Wars, and a few rare others, it belongs on a short list of popular successes that cinephiles continue to celebrate, write, and talk about exhaustively. And to the degree that there’s never enough to be said about a film like this, it’s enough to stand back in awe and revel in its greatness.

But forget for a moment that Jaws played a major role in an artistic downturn in cinema that may have resulted in the dumbification of U.S. audiences and the overt commercialization of films into elaborate marketing ploys. Forget the three increasingly forgettable-to-downright-terrible sequels that followed, and the only sometimes entertaining (see Piranha, 1978) offshoots. Reflect instead on what a carefully composed and genuinely great piece of filmmaking Steven Spielberg accomplished through unimaginable circumstances. Consider how every aspect of the film—the poster, the music, the thrills, the wry comic dialogue—is nothing short of iconic. Every scene shows a master at work to create something uniformly consumable and visually distinct, amounting to a purity assembled through an incredible technical and narrative artistry. How easy it is, perhaps due to the years of oversaturation, to take Jaws for granted! In its most basic understanding, it is a cherished picture of unrelenting suspense. But it remains such a readable, unlikely cognitive experience because there is so much to which we can assign meaning. Thus, Jaws will never lose its potency, no matter how many times one sees it. Along with Casablanca, Star Wars, and a few rare others, it belongs on a short list of popular successes that cinephiles continue to celebrate, write, and talk about exhaustively. And to the degree that there’s never enough to be said about a film like this, it’s enough to stand back in awe and revel in its greatness.

Bibliography:

Andrews, Nigel. Nigel Andrews on Jaws. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999.

Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998.

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Gottlieb, Carl. The Jaws Log. New York: Newmarket Press, 2005.

Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen. Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Heath, Stephen. “Jaws, Ideology, and Film Theory”. In Nichols, Bill. Movies and Methods: An Anthology, Volume II. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Quirke, Atonia. Jaws. London: British Film Institute Modern Classics, BFI Publishing, 2002.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review