The Definitives

It Happened One Night (1934)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

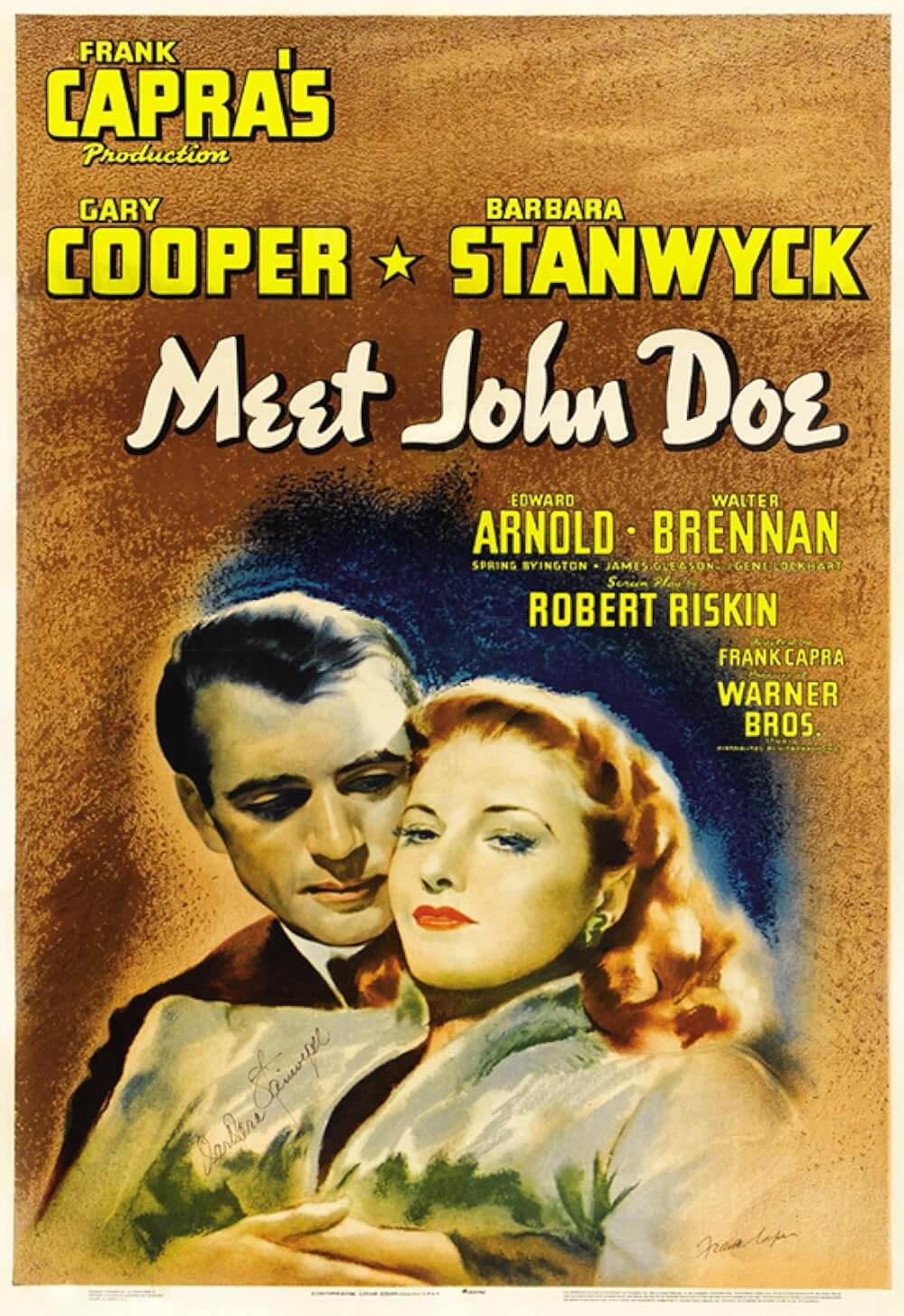

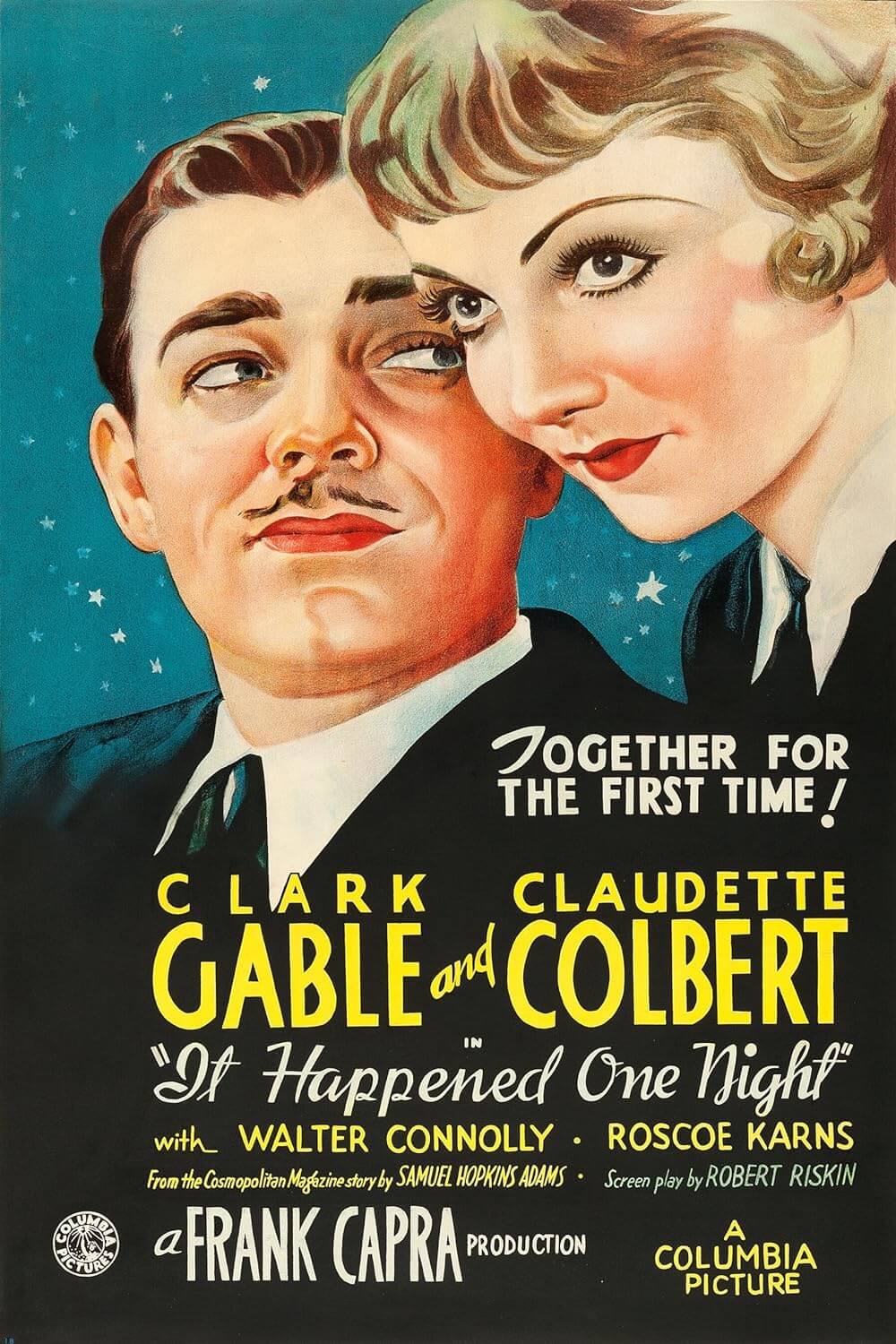

It Happened One Night holds a place among the great classic Hollywood comedies because its director, Frank Capra, knew how to tap into the social consciousness of his audience. He also knew how to pick crowd-pleasing stars. The modest screwball setup involves a long journey on the road and two mismatched protagonists who inevitably fall in love. Despite its heartwarming “love conquers all” theme, some of what makes Capra’s film so universal can be understood through a specific historical lens. Released by Columbia Pictures in 1934, It Happened One Night acknowledges the Depression-era landscape’s poverty, hunger, and exploitation. During the cross-country voyage of Clark Gable’s ambitious reporter and Claudette Colbert’s spoiled heiress, the two become members of a community that, through their help and support of one another, triumphs over adversity. But those social underpinnings do not explain the film’s effortless charm and unlikely elegance. Quite simply, It Happened One Night would have been something far more conventional and without lasting significance had it been made by another director or featured different stars. That indefinable quality keeps bringing us back in an attempt to articulate what makes the film so overwhelmingly engaging. But after nearly a century of critics, scholars, and moviegoers singing its praises, the answer to what makes the film endure remains simple, if rather dissatisfying: Movie Magic.

The story follows heiress Ellie Andrews (Colbert), whose father (Walter Connolly) disapproves of her wedding to the social climber and aviator “King” Westley (Jameson Thomas). “He’s a fake,” Ellie’s father tells her, but he’s also a means to her freedom. Intending to reconnect with Westley, she escapes her father’s Miami yacht and plans to travel to New York by bus. With private detectives and reporters searching for the missing heiress, Ellie meets Peter Warne (Gable), a recently unemployed reporter who hatches a scheme: he will use his roguish street smarts to help the inexperienced Ellie reach her destination, and in the process, deliver an exclusive about Ellie’s journey. Along the way, Ellie and Peter barely scrape by, traveling by bus and hitchhiking, and spending nights in rough conditions. In due course, Ellie soon forgets why she married Westley and Peter begins to overlook Ellie’s brattish tendencies. On their final night together, Ellie wakes up to find Peter gone. Feeling abandoned, she calls her father and makes wedding plans with Westley. But Peter has driven to his editor (Charles C. Wilson) to pitch the story of an heiress and reporter who fall in love on the road. In classic romantic comedy fashion, the climactic confusion leads to Peter and Ellie finally embracing in a swoon-worthy finale.

Capra, screenwriter Robert Riskin, and author Myles Connolly (the director’s uncredited collaborator) fleshed out It Happened One Night in a small adobe cottage at La Quinta Hotel, some twenty miles outside of Palm Springs. Here, the trio made significant alterations to the source material—author Samuel Hopkins Adams’ short story “Night Bus,” published in the pages of Cosmopolitan in 1933. No one involved was enthusiastic about It Happened One Night initially; Riskin told Capra biographer Joseph McBride, “We were desperate for a story for Capra. We grabbed the first thing that came along.” The material was all too familiar. Capra had made something similar in Platinum Blond (1931), starring Robert Williams and Jean Harlow, also about a rough-around-the-edges reporter falling for a woman from high society. The director called the team “chumps” for buying the story rights to “Night Bus,” given the similarities and untenable characters. Yet despite these early reservations, the film became a rousing success, so much so that Columbia afforded the group the rare luxury to work away from the studio property when they started developing their next several projects for the studio, so they could repeat the formula that had worked so well for It Happened One Night. Out of superstition, they returned to the same cottage, which Capra called “our Shangri-La for script-writing in the coming years” in his autobiography.

As the team worked to reshape the source material into It Happened One Night and align it with Capra’s sensibilities, the problem became apparent: they didn’t particularly like Adams’ characters. So they set out to rewrite the entire story and make the main characters more agreeable. Many of the structural changes originated with Connolly. “Your leading characters are non-sympathetic,” Connolly told Capra, in a scene from the director’s autobiography. “People can’t identify with them.” Connolly called Ellie “a spoiled brat, a rich heiress. How many spoiled heiresses do people know? And how many give a damn what happens to them?” Connolly also had words about Peter, who, in the original story, was a college-educated chemist. Riskin’s initial draft made him an artist. But Connolly, a former newspaperman, suggested they change Peter to a hardened reporter. “I don’t know any vagabond painters,” Connolly explained, “and the man I don’t know is the man I’m apt to dislike, especially if he has no ideals […] no dragons to slay.” Audiences were familiar with the newspaperman trope in Hollywood cinema, and giving the character a career motivation heightened the stakes. Thus, Peter became a “crusading” reporter determined to deliver a scoop to his unconvinced editor.

As the team worked to reshape the source material into It Happened One Night and align it with Capra’s sensibilities, the problem became apparent: they didn’t particularly like Adams’ characters. So they set out to rewrite the entire story and make the main characters more agreeable. Many of the structural changes originated with Connolly. “Your leading characters are non-sympathetic,” Connolly told Capra, in a scene from the director’s autobiography. “People can’t identify with them.” Connolly called Ellie “a spoiled brat, a rich heiress. How many spoiled heiresses do people know? And how many give a damn what happens to them?” Connolly also had words about Peter, who, in the original story, was a college-educated chemist. Riskin’s initial draft made him an artist. But Connolly, a former newspaperman, suggested they change Peter to a hardened reporter. “I don’t know any vagabond painters,” Connolly explained, “and the man I don’t know is the man I’m apt to dislike, especially if he has no ideals […] no dragons to slay.” Audiences were familiar with the newspaperman trope in Hollywood cinema, and giving the character a career motivation heightened the stakes. Thus, Peter became a “crusading” reporter determined to deliver a scoop to his unconvinced editor.

Among their adjustments to Adams’ short story, they changed Ellie’s central flaw from being an heiress to her taking her privilege for granted. With Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew in mind, the writers turned Peter into the everyman who reigns in Ellie, thereby following a traditional formula where a man shows an unruly woman what she wants and needs, and what’s more, how she should see the world. Removing most of the nuances from Adams’ text, Ellie (originally named Elspeth) became a complaining, mostly helpless, and virginal young woman oblivious to the “real world” from which she has been sheltered by her wealth and privilege. Peter must educate her in a series of comic humiliations, humblings, and reality checks to relieve her of her naïveté—not to mention her chastity, in a detail Capra plays up in the script (the original story presented the character as better versed in matters of sex). The changes shifted from subtle literary material to a familiar Hollywood confection that would be propelled and elevated by sheer star power. Even so, the standard setup failed to interest Columbia’s biggest stars, while other studios refused to loan out their top talent.

“Nobody wanted to play in It Happened One Night,” Capra observed later. Myrna Loy and Miriam Hopkins turned down the leading role. Bette Davis wanted to star, but Warner Bros. refused to loan her out. Capra wanted Robert Montgomery to play the lead, but Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s head Louis B. Mayer denied access to his top star. Mayer agreed to give them Gable instead. Apart from a smattering of appearances as an extra, Gable had only been acting in pictures since signing with MGM in 1931. Although he was a favorite of Hollywood gossip columnists and star magazines, he had yet to be dubbed “The King of Hollywood.” Actually, Gable wanted to quit Hollywood. MGM gave him limited roles, casting him as gangsters and reporters, which left Gable frustrated by his lack of pay and overworked schedule (he appeared in eleven features in 1931, five in 1932, and four in 1933). When Gable complained to Mayer, the studio head retaliated with the It Happened One Night deal, which he considered a surefire dud. So when Gable met with Capra initially, he showed up to their first meeting drunk and took the script begrudgingly. By contrast, Colbert had been around longer than Gable, and she too would reach a career milestone in 1934, the same year she starred in Cleopatra and Imitation of Life. Colbert had a vacation planned around the scheduled shoot, but she wanted to work with Gable. She told Capra that if he could wrap production in four weeks and secure her a $50,000 payday, she would star in the picture. Concerned that his budget was only $325,000, Capra took the gamble and delivered on his promise, completing on time and with on-set improvisation that gave the film its relaxed quality.

Some of the ad-libbing included It Happened One Night’s many scenes that tested the boundaries of the Motion Picture Production Code. Officially, Will Hays spearheaded the so-called Hays Code in 1930. It would not be enforced until July 1934, when the Production Code Administration under Joseph Breen began issuing the seal required for any film to earn theatrical distribution. Though, even before the Code’s enforcement, Capra and other filmmakers knew not to push its strictures, if only to play the game and ensure their movie’s box-office potential. Still, It Happened One Night, debuting in February 1934, earns recognition as one of the last major “Pre-Code” releases, and it would surely be a different film had it been released even six months later under the Code. The entire concept of an unmarried man and woman spending the night together in the same room would have been nixed. The same goes for Shapeley (Roscoe Karns), a fast-talking bus rider with lines spoken to Ellie such as “Shapley’s the name and that’s how I like ‘em” or “When a cold mama gets hot, boy, she sizzles.” Gone would be the scene when Ellie appears in her semi-transparent camisole. And most significantly, they would have removed the scene where Ellie refuses to leave Peter’s side of the bedroom, and Gable unbuttons his shirt. “Perhaps you’re interested in how a man undresses,” he says, revealing his bare chest—and no undershirt, which, according to unattributable Hollywood legend, caused a decline in the undershirt market after the film’s release.

Some of the ad-libbing included It Happened One Night’s many scenes that tested the boundaries of the Motion Picture Production Code. Officially, Will Hays spearheaded the so-called Hays Code in 1930. It would not be enforced until July 1934, when the Production Code Administration under Joseph Breen began issuing the seal required for any film to earn theatrical distribution. Though, even before the Code’s enforcement, Capra and other filmmakers knew not to push its strictures, if only to play the game and ensure their movie’s box-office potential. Still, It Happened One Night, debuting in February 1934, earns recognition as one of the last major “Pre-Code” releases, and it would surely be a different film had it been released even six months later under the Code. The entire concept of an unmarried man and woman spending the night together in the same room would have been nixed. The same goes for Shapeley (Roscoe Karns), a fast-talking bus rider with lines spoken to Ellie such as “Shapley’s the name and that’s how I like ‘em” or “When a cold mama gets hot, boy, she sizzles.” Gone would be the scene when Ellie appears in her semi-transparent camisole. And most significantly, they would have removed the scene where Ellie refuses to leave Peter’s side of the bedroom, and Gable unbuttons his shirt. “Perhaps you’re interested in how a man undresses,” he says, revealing his bare chest—and no undershirt, which, according to unattributable Hollywood legend, caused a decline in the undershirt market after the film’s release.

To be sure, many of the most memorable moments and flirtations between the two characters would have been cited by Breen. When Ellie and Peter spend the night in a cabin at an auto camp, she raises some questions about the sheet he has strung up to separate the room. “That, I suppose, makes everything all right?” she asks. Peter claims to like his privacy so symbolically raises the sheet. “Behold, the Walls of Jericho. Maybe not as thick as the ones Joshua blew down with his trumpet, but a lot safer. You see, I have no trumpet.” Although the writers didn’t have to contend with Breen’s watchful edits from the Production Code office, they still danced around matters of sex with innuendo and symbolism. And it doesn’t take much to understand what the wall represents. The blanket is there to disguise what goes on behind it and protect each other from, shall we say, an invasion. Moreover, Peter situates himself not as the invading force, the Israelites who sounded their trumpets when they invaded Canaan in the Book of Joshua. Instead, he tells Ellie, “Do you mind joining the Israelites?”—meaning, she should get on her side of the blanket wall, with the rest of the invading force. In his metaphor, Ellie is the aggressor, and he’s with the Canaanites hiding behind the wall. In the film’s final shots, when the wall comes down, and afterward the lights go out, the symbolism allows Capra to infer the consummation of their relationship without having to show Peter and Ellie in a passionate embrace.

Along with the allusion of Ellie the aggressor-Israelite, it’s worth noting that, if Ellie seems virginal and naive, she also has a voracious appetite. Literary and early Hollywood symbolism often treated hunger as a shorthand analogy for sexual appetite, and It Happened One Night features no end of references to food and hunger—they eat donuts, eggs, and carrots on the road. Of course, hunger was an everyday reality for many during the Depression. But the kind of hunger Ellie feels isn’t only for food. Coming from the vacuous high society, she finds herself drawn to Peter in all his earthiness—epitomized by his fondness for that most phallic of vegetable roots, the raw carrot. When, out of desperate hunger, Ellie resolves to try a bite, she realizes that raw carrots aren’t so bad, after all. The symbolism at work here is unmistakable in sexual and social terms. Ellie’s life before Peter was passive, doing what has been expected of her and staying within her class. Her life has been isolated and empty, so she remains unfulfilled and hungry. Enter Peter’s carrot. (About that carrot: Bugs Bunny borrowed Gable’s carrot-munching and rebranded it, but Bugs’ carrot routine became so iconic that rabbit owners started feeding carrots to their rabbits. Alas, carrots contain a high sugar content, which causes rabbits all manner of health problems. In other words, Gable’s Peter Warne is responsible for a lot of sick bunnies.)

It Happened One Night became a key film about the Great Depression. The crash started in 1929 and lasted a decade, causing hardships across the United States that affected everyone. So in the film’s first scene when Ellie, who insists she’s on a hunger strike, throws a tantrum that culminates with flipping over her father’s steak dinner, it’s a shocker, prompting her father to slap her across the face. Both of them take a beat. Ellie has never been slapped. Her father has never slapped her. But when people are starving throughout the country, steak is a luxury. Ellie’s action not only establishes her spoiled nature but her ignorance about the average American’s hardships. Seldom did Hollywood give audiences such reality checks, unless it came from rarities such as Charlie Chaplin (City Lights, 1931), a torn-from-the-headlines gangster picture (The Public Enemy, 1931), or the occasional work of social realism (Make Way for Tomorrow, 1937). Most moviegoers flocked to theaters during the 1930s for a brief respite from the economic downswing in their lives, and they often found escapist stories about well-to-dos: sophisticated Greta Garbo period pieces (Queen Christina, 1933), Marlene Dietrich melodramas (Shanghai Express, 1932), and Ernst Lubitsch’s comedies that poked fun at the European upper classes (The Smiling Lieutenant, 1931).

It Happened One Night became a key film about the Great Depression. The crash started in 1929 and lasted a decade, causing hardships across the United States that affected everyone. So in the film’s first scene when Ellie, who insists she’s on a hunger strike, throws a tantrum that culminates with flipping over her father’s steak dinner, it’s a shocker, prompting her father to slap her across the face. Both of them take a beat. Ellie has never been slapped. Her father has never slapped her. But when people are starving throughout the country, steak is a luxury. Ellie’s action not only establishes her spoiled nature but her ignorance about the average American’s hardships. Seldom did Hollywood give audiences such reality checks, unless it came from rarities such as Charlie Chaplin (City Lights, 1931), a torn-from-the-headlines gangster picture (The Public Enemy, 1931), or the occasional work of social realism (Make Way for Tomorrow, 1937). Most moviegoers flocked to theaters during the 1930s for a brief respite from the economic downswing in their lives, and they often found escapist stories about well-to-dos: sophisticated Greta Garbo period pieces (Queen Christina, 1933), Marlene Dietrich melodramas (Shanghai Express, 1932), and Ernst Lubitsch’s comedies that poked fun at the European upper classes (The Smiling Lieutenant, 1931).

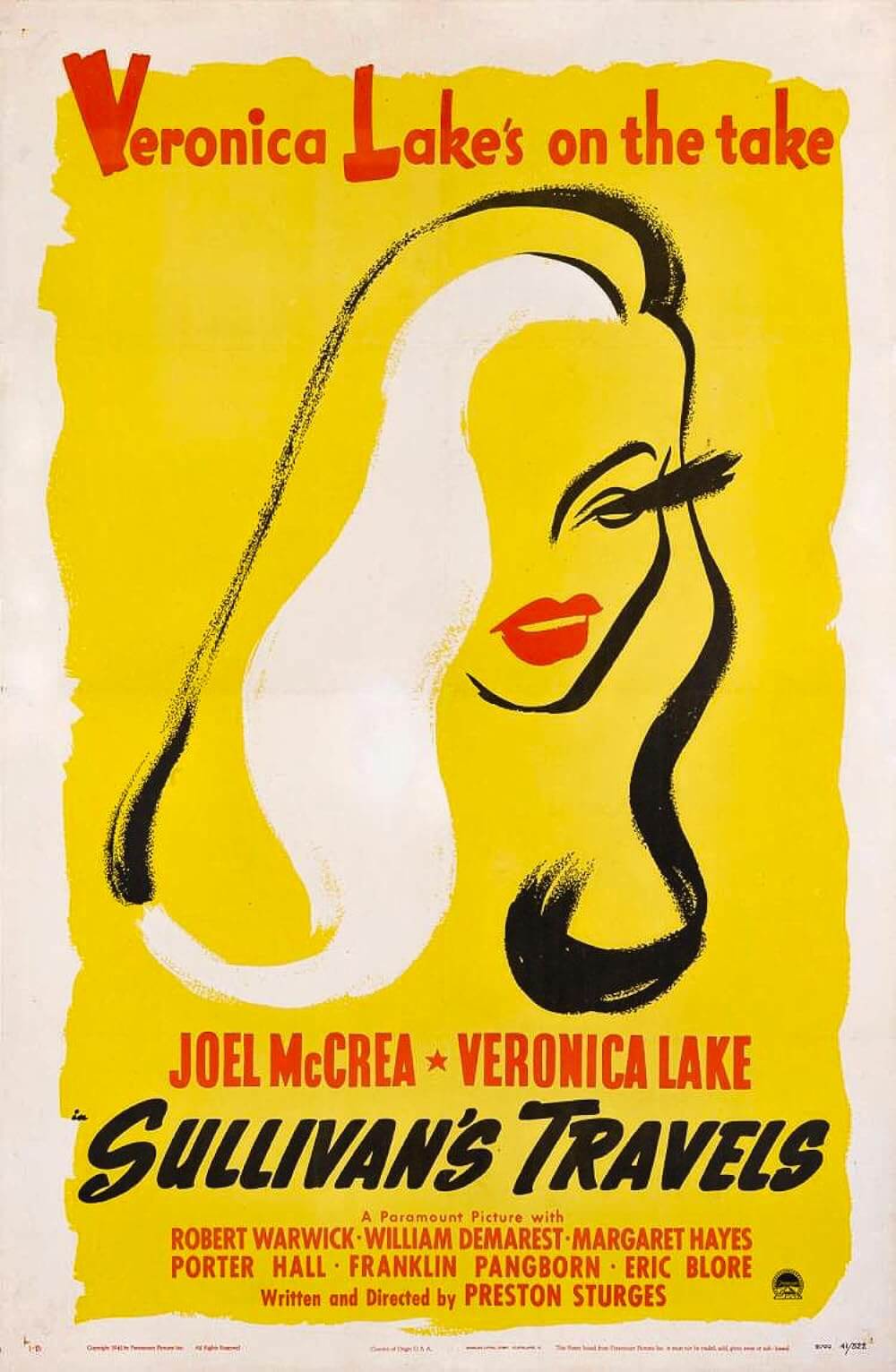

In a few tender scenes, It Happened One Night acknowledges the Depression’s effect on the majority of Americans without turning the film into overt social realism—in a balance of comedy and reality that Preston Sturges would borrow for Sullivan’s Travels in 1941. One scene finds a woman on the night bus passing out from hunger, and Ellie gives her young boy Peter’s last ten-dollar bill to help. The road movie setup, too, offers a cross-section of downtrodden life struggling to make do. The way It Happened One Night exposes Ellie to another class proves rare for a 1930s picture. Typically, the upper class helped the lower class, the lower class thumbed their nose at the upper class, or both classes inhabited their own bubble. Viewers with less money often watched those who had more in Hollywood films, sometimes to escape into the good life, sometimes to censure its privilege. Such broad ways of portraying and understanding class rarely result in productive discourse, and, as a result, an Us vs. Them dichotomy became the standard against which many comedies upset the norm to hilarious effect. While exceptions do exist, none would become so sensational as It Happened One Night, which went on to inspire similar class intermingling in My Man Godfrey (1936) and The Lady Eve (1941). Its opposite-classes-attract juxtaposition was not without antecedents, but Capra instilled such a milestone for the theme that it persisted in romantic comedies from Harold and Maude (1971) to Pretty Woman (1990).

In another way, the film can be summarized by the early headline, “Ellie Andrews Escapes Father”—but perhaps it should be “Ellie Andrews Escapes One Father, Finds Another.” Treated like a child by her father, Ellie finds herself infantilized by another sort of fatherly figure in Peter. He calls her an “ungrateful brat,” confiscates her money and then distributes it back like an allowance, and offers her instructions on how to properly dunk a donut or hitchhike. And when detectives knock on the motel door, looking for the missing heiress, Peter makes up a story and protects Ellie in a fatherly manner, even if it’s just protecting his interest as a reporter with a scoop. In romantic comedies of this breed, a man often lectures a woman and brings some rationality to her irrational ways of thinking—a none-too-progressive notion. Scholar Karyn Kay argues that these dynamics in screwball comedies “end up as homiletics about the need for wives to obey husbands,” and despite all the boundary-pushing, It Happened One Night occupies a traditional and patriarchal ideology. Given how they end up, Kay’s point cannot be easily dismissed; however, there are deviations. After all, the story begins with Ellie wanting to escape from her social role as a rich man’s daughter or repressed trophy wife; she is not a passive character in that sense, just unworldly and inexperienced. While Ellie learns about the world in her time with Peter, she symbolically learns about her desire and independence as a person capable of seeking out and fulfilling that desire.

Moreover, some of the film’s funniest moments occur when Ellie proves she can do more than her spoiled child persona seems capable. The student becomes the teacher when Ellie famously lifts up her skirt to reveal her leg, controlling her sex appeal to create an alternative to sticking out a thumb to hitchhike. The appearance of Ellie’s leg brings the next car to a screeching halt, thus demonstrating her knowing sexuality to Peter, and elevating her from the status of child-student to someone he sees as a romantic interest. Indeed, the film isn’t entirely a comedy that reinforces the tropes of submissive women and controlling men. Peter, too, suggests that he’s more interested in sharing his life with a woman than dominating her. On their final night together, they talk honestly about their desires, with only the Wall of Jericho to separate them. Peter dreamily admits to his deserted island fantasy with a woman to experience “nights when you and the moon and the water all become one, and you feel that you’re part of something big and marvelous.” It’s at that moment when Ellie steps around the separator. At first, the medium shot appears normal enough from Peter’s perspective. Then it cuts to a soft-filtered close-up, suggesting that Peter now sees Ellie as a love interest. She approaches him with tears filling her eyes. “Take me with you,” she sobs, declaring her love. But he sends her back to the other side of the wall.

Moreover, some of the film’s funniest moments occur when Ellie proves she can do more than her spoiled child persona seems capable. The student becomes the teacher when Ellie famously lifts up her skirt to reveal her leg, controlling her sex appeal to create an alternative to sticking out a thumb to hitchhike. The appearance of Ellie’s leg brings the next car to a screeching halt, thus demonstrating her knowing sexuality to Peter, and elevating her from the status of child-student to someone he sees as a romantic interest. Indeed, the film isn’t entirely a comedy that reinforces the tropes of submissive women and controlling men. Peter, too, suggests that he’s more interested in sharing his life with a woman than dominating her. On their final night together, they talk honestly about their desires, with only the Wall of Jericho to separate them. Peter dreamily admits to his deserted island fantasy with a woman to experience “nights when you and the moon and the water all become one, and you feel that you’re part of something big and marvelous.” It’s at that moment when Ellie steps around the separator. At first, the medium shot appears normal enough from Peter’s perspective. Then it cuts to a soft-filtered close-up, suggesting that Peter now sees Ellie as a love interest. She approaches him with tears filling her eyes. “Take me with you,” she sobs, declaring her love. But he sends her back to the other side of the wall.

However, the hint of parental oversight in the Peter-Ellie relationship is deceiving. When Ellie’s father asks whether Peter genuinely loves her, he replies, “What she needs is a guy that’d take a sock at her once a day whether it was coming to her or not.” That sounds good to Ellie’s father. Peter seems to occupy the classical film role of husband-parent that Golden Age Hollywood films often reserved for childish or ill-tempered women characters. At first glance, Peter is the every-man-is-an-island archetype without any ties in the world, and he plays at being a fatherly figure who, at the auto camp, orders Ellie to get out of bed and get dressed—he even buys the groceries and cooks her breakfast. That he must teach her the practical realities of life on the road reinforces his view of the spoiled rich as helpless and impractical. His focus on taking care of her, as opposed to acknowledging her as a woman, and an attractive woman, reveals his fear that his heart will soften for Ellie and put his story at risk. Eventually, he realizes that his newspaper scoop is his own love story. What is more, when Ellie becomes a runaway bride at her wedding to Westley at the end, it’s because she realizes that she loves Peter when he turns down her father’s money—which is one of the many ways Peter is not like her father. She wants “somebody that’s real, somebody that’s alive,” the implication being that privilege corrupts and renders people like Westley hollow (this is a man who insists upon arriving at his wedding in an autogyro, after all). Peter wants an authentic partner as well, and he eventually realizes that Ellie has the rebellious spirit that endears him to her.

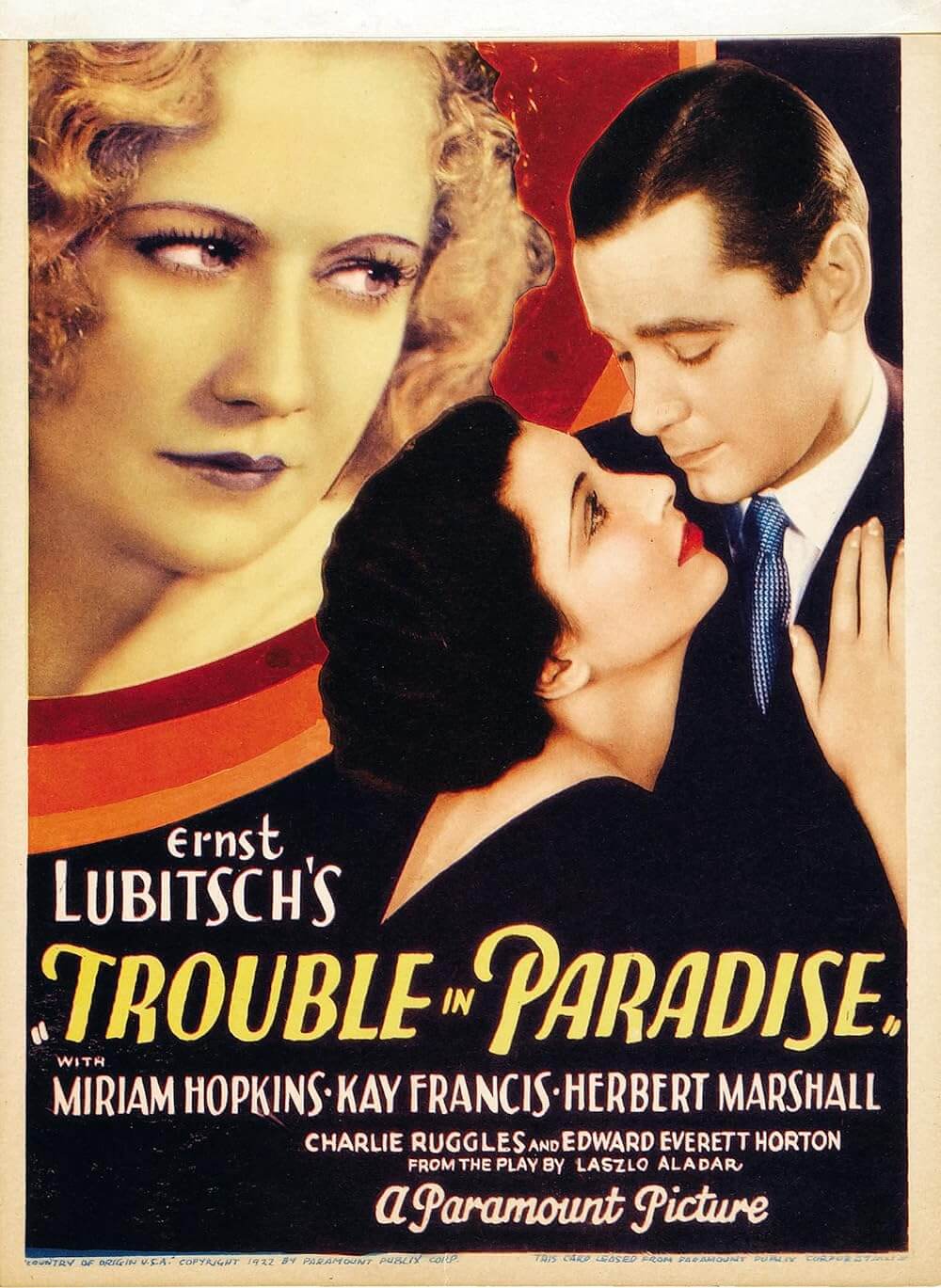

Scholars such as Stanley Cavell have called It Happened One Night a comedy of remarriage; though, it’s not a traditional example—where a couple goes through marriage proceedings, has doubts about their decision and separates, only to be brought back together again out of love. For that, see Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise (1932). Rather, Ellie’s so-called remarriage follows an off-screen annulment of her previous marriage to Westley, and she doesn’t so much renew or restate her vows as enter into an alternative, off-screen marriage to Peter. Her remarriage is a symbolic union that aligns her not with another father figure to replace the one she escaped in the opening scene, but someone as free-spirited as Peter Warne. Note how Peter empowers Ellie to explore her freedom in the world, unlike her father, who, under the strictures of the upper class, shielded from the outside, told her how to behave and what to wear, and robbed her of privacy. It Happened One Night, then, is what Capra scholar Raymond Caney called another of the director’s investigations into “the great American project of fashioning a self and finding a place for it in the world that can live up to the claims that the imagination places upon it.” It’s a theme Capra, a self-made Italian immigrant, often worked into his pictures.

After a record-breaking debut on February 23 at Radio City Music Hall, It Happened One Night waned at the box office. Most news outlets praised the treatment and talent but acknowledged the material didn’t break boundaries. The critic in the New Republic claimed it was “better than it has any right to be.” Mordaunt Hall’s review in The New York Times praised Colbert and Gable, noting that the film was “blessed with bright dialogue and a good quota of relatively restrained scenes.” Expanding across the US, it gained momentum with audiences before becoming a hit. Capra observed, “The people discovered that picture.” Audiences flocked to see the film’s stars. Gable’s role (and bare chest) catapulted him into superstardom. Colbert’s exposed leg didn’t hurt either. Columbia earned over $2.5 million back on its $325,000 budget. But the biggest win for the talent involved came the next year, when It Happened One Night took home Oscars in each of the “big five” categories: Outstanding Production (now called Best Picture), Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adaptation (now Best Adapted Screenplay). The combination of receipts and awards also earned Capra newfound autonomy and freedoms at Columbia, where he would make his next five pictures.

After a record-breaking debut on February 23 at Radio City Music Hall, It Happened One Night waned at the box office. Most news outlets praised the treatment and talent but acknowledged the material didn’t break boundaries. The critic in the New Republic claimed it was “better than it has any right to be.” Mordaunt Hall’s review in The New York Times praised Colbert and Gable, noting that the film was “blessed with bright dialogue and a good quota of relatively restrained scenes.” Expanding across the US, it gained momentum with audiences before becoming a hit. Capra observed, “The people discovered that picture.” Audiences flocked to see the film’s stars. Gable’s role (and bare chest) catapulted him into superstardom. Colbert’s exposed leg didn’t hurt either. Columbia earned over $2.5 million back on its $325,000 budget. But the biggest win for the talent involved came the next year, when It Happened One Night took home Oscars in each of the “big five” categories: Outstanding Production (now called Best Picture), Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adaptation (now Best Adapted Screenplay). The combination of receipts and awards also earned Capra newfound autonomy and freedoms at Columbia, where he would make his next five pictures.

It Happened One Night has had an immeasurable effect on the romantic comedy genre, which has paid homage to and spoofed Capra’s picture countless times. Whenever a character uses their sex appeal to stop a passing car, whenever a sheet separates a room, whenever life on the road provides a life-altering experience, whenever a bride changes her mind at the last minute, and whenever two bickering adults fall in love, It Happened One Night is among the influences. The film endures not only for its many charms and the chemistry between Gable and Colbert but for its portrait of the average American. The scenes on the bus, such as the passengers singing “The Man on the Flying Trapeze” together, would become staples of the road movie, even if they add nothing to the forward momentum of the plot. Capra included the scene to portray the simple joys of an everyday experience, far removed from the usual trappings of a Hollywood romantic comedy. John Gassner wrote in his introduction to the screenplay, “Its adult approach to love was a welcome departure from saccharine romance […] It Happened One Night proved a signpost on Hollywood’s journey from adolescence to maturity.” The film’s particular brand of maturity rests in its willingness to not only embrace the airy trappings of a Hollywood romance but recognize that people struggling with the Depression survive on love.

Strong arguments have been made against It Happened One Night, suggesting its sexual politics are outdated and conservative, while its narrative and characters are simplistic examples of the rugged father-figure man who brings rationality to his spoiled object of desire. But a close reading shows that Peter and Ellie defy the usual archetypes. In any case, the experience of watching the film has a miraculous way of overcoming such readings. “There was something, indeed, about It Happened One Night that defied description or analysis,” observed McBride. If the film does not level the walls between men and women, upper classes and lower, it also does not supply boilerplate Depression-era escapism. Its escape suggests love can happen in the most inelegant of places—in rundown motels, shacks, and wherever else the average American affected by the economic downturn had been spending their nights. Viewers at the time recognized these places from their lives and saw in Gable and Colbert the hopes and dreams to which they aspired. Only a filmmaker with Capra’s empathy for the average American could have made It Happened One Night feel so relatable and reflective, leaving us with its many charms and the boundless chemistry of its stars.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

Carney, Raymond. American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Harvard University Press, 1984.

—. “Knowledge as Transgression: Mostly a Reading of ‘It Happened One Night.’” Daedalus, vol. 109, no. 2, The MIT Press, 1980, pp. 147–75, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024670. Accessed 22 February 2022.

Gassner, John, and Dudley Nichols (editors). Twenty Best Film Plays. 1943; repr. Garland Press, 1977.

Gottlieb, Sidney. “From Heroine to Brat: Frank Capra’s Adaptation of ‘Night Bus (It Happened One Night).’” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, Salisbury University, 1988, pp. 129–36, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43797541. Accessed 22 February 2022.

Kay, Karyn. “Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave, or Putting the Screws to Screwball Comedy.” Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology, ed. Karyn Kay and Gerald Peary. E.P. Dutton, 1977.

McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Touchstone Books, 1992.

Mizejewski, Linda. It Happened One Night. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Nehme, Farran Smith. “It Happened One Night: All Aboard!” Criterion.com, 17 November 2014. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3369-it-happened-one-night-all-aboard. Accessed 22 February 2022.

Poague, Leland A. “‘As You Like It’ and ‘It Happened One Night’: The Generic Pattern of Comedy.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 4, Salisbury University, 1977, pp. 346–50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43796090. Accessed 22 February 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review