The Definitives

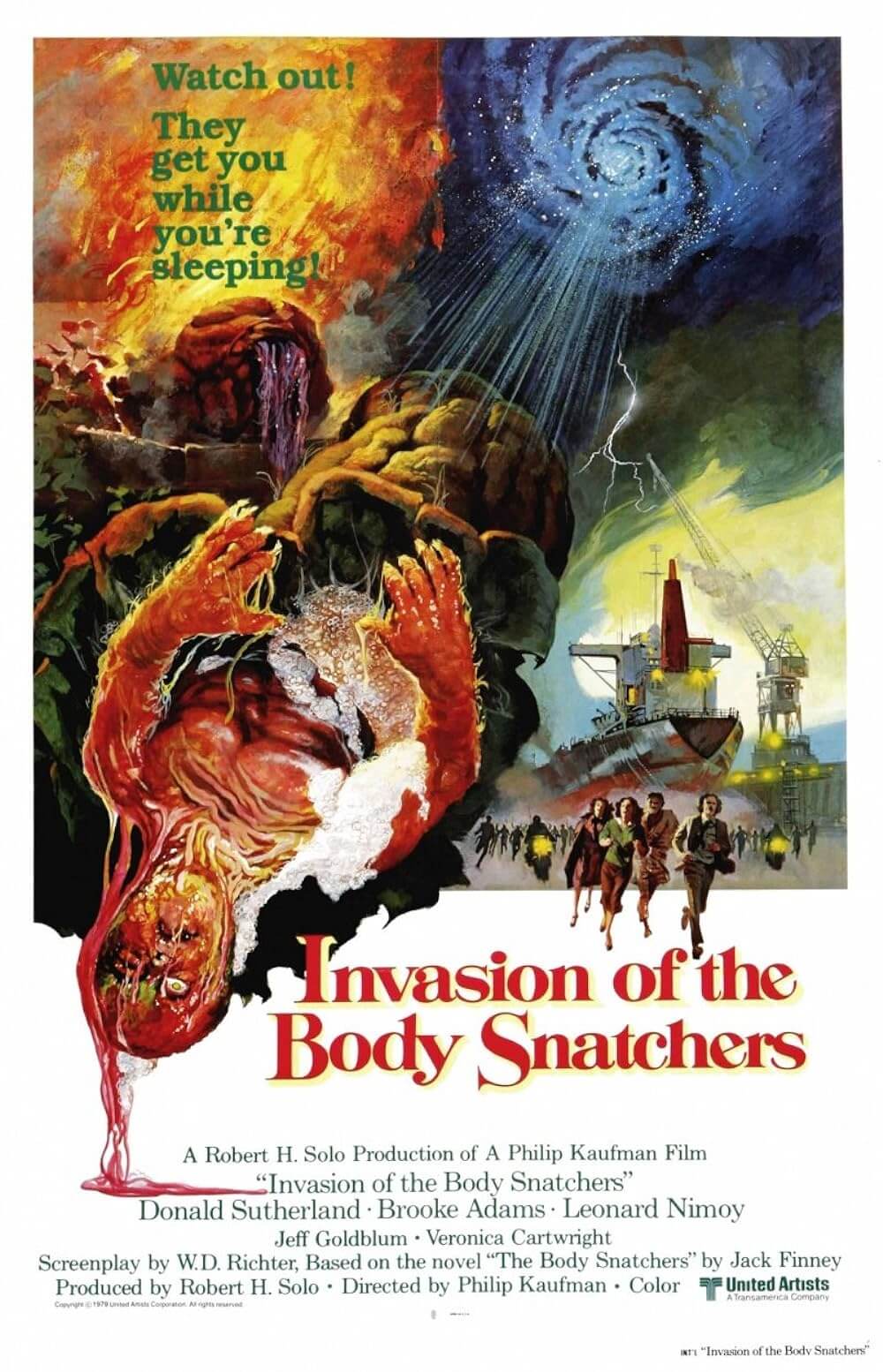

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

While they sleep, an otherworldly threat infiltrates San Francisco residents and replicates them into emotionless duplicates. All of their liberalism and culture are stripped away as they become drones in an alien plot. More than most, their individuality, so valued in this city, is gone, leaving them mere shadows of their former selves. In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, director Philip Kaufman takes great care to arrange his film so that it unfolds with equal measures of existential insight and heart-wrenching terror. Clever visual touches and inspired humor have been layered into a film that seems alive like few others of its kind. All of the usual elements are in place for a familiar brand of a conspiratorial alien takeover. Still, Kaufman enhances them with a vitality and playfulness behind the camera, actors of incredible skill, and an offbeat, subtle wit that lies beneath the surface. But perhaps the film’s most significant touch is the setting of San Francisco circa 1978, where Generation Me struggled in its search for identity against an urban expansion movement that signified social homogenization. It’s a hopeless world for characters whose narcissistic drives make them perfect targets, not unlike our current society, where the individual remains physically isolated yet somehow gratified by social media and cultural bubbles. A spiritual sequel and remake of Don Siegel’s 1956 original, Kaufman’s film remains an unmatched masterpiece among the many based on Jack Finney’s oft-adapted novel, The Body Snatchers.

Finney’s original book first appeared as a serial in Collier’s Magazine in 1954 and was expanded into hardback publication the next year. Despite its enduring legacy, critics responded with censures of Finney’s poorly researched science, illogical characters, and familiar plotting. Galaxy magazine’s book critic Groff Conklin remarked, “Too many sci-fi novels lack outstanding originality, but this one lacks it to an outstanding degree.” After all, by 1955, several more adept science-fiction authors had already explored the notion of a conspiratorial alien takeover through duplication and replacement. John W. Campbell Jr. released the novella Who Goes There? in 1938, a spooky tale about researchers in Antarctica who are exposed to an alien organism that replicates its victims. Campbell’s influential story inspired Howard Hawks’ loosely adapted production, The Thing from Another World (1951), and John Carpenter’s more faithful adaptation, The Thing (1982). In 1951, Robert A. Heinlein published The Puppet Masters, a politically charged thriller about an American spy uncovering an alien takeover in the government’s ranks; it was adapted to film in 1994 (and starred Donald Sutherland, like Kaufman’s film). In each case, the original book exploited American paranoia about Reds under the bed (a term coined from political cartoons in the early days of Communist paranoia). The thought that anyone—your next-door neighbor, family member, or country’s leaders—could be a Communist in secret fueled the flames of McCarthyism, making these novels wonderful escapism with a relevant subtext.

By the mid-1950s, director Don Siegel had observed blacklists and rampant Red Scare mistrust sweep the country as an undeniable Communist presence in the United States spread. Versed in edgy, low-budget programmers with an undercurrent of acerbic skepticism, Siegel resolved to underline this suspicious climate with an adaptation of Finney’s book. Along with writer Daniel Mainwaring, Siegel delivered a cheap but unforgettable B-movie with Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The Communist stand-ins are “pod people” determined to impose conformity on the human population. In bookend scenes, the film’s protagonist, Kevin McCarthy’s Dr. Miles Bennell, recounts his story about a sudden rash of patients in his small town, all of whom claim that an impostor has replaced a loved one. Bennell assumes they’re all suffering from mass hysteria, a sort of far-reaching case of Capgras syndrome. The delusion that your loved ones have been replaced was named after the French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras, who first described the disorder in 1923. But after discovering evidence of an unstoppable alien presence and their pods being shipped out of town for a worldwide takeover, Bennell takes to the streets, shouting, “They’re here already! You’re next! You’re next!” In the epilogue, the psychiatrist listening to Bennell’s account learns that his fantastic story is true and calls the authorities. Distributors at Allied Artists made the begrudging Siegel shoot an ending where the day is presumably saved (although theatrical reissues in 1979 removed the bookend scenes). Kaufman had no such concessions in his remake.

Philip Kaufman was born in Chicago in 1936 to Jewish-German parents. After earning a degree in history at the University of Chicago, he attended Harvard Law School for a year. At that point, he returned to his alma mater for a postgraduate degree in history. He and his wife Rose moved to San Francisco in 1960. After a backpacking vacation across Europe, where they took in the French and Italian New Wave scene in Europe’s cinemas, Kaufman was determined to become a filmmaker. Returning to the U.S., he proceeded to shoot Goldstein, a project based on his unfinished novel, which he co-wrote and co-directed with Benjamin Manaster. Goldstein would take him two years to complete, but it would result in the Prix de la Nouvelle Critique at the Cannes Film Festival in 1964. The following year, he released Fearless Frank, which featured the screen debut of actor John Voight. Kaufman went on to write and direct adventures like The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1971) and The White Dawn (1974) early in his career. He even contributed to concept talks for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), for which he gave George Lucas the idea to use the Ark of the Covenant as the MacGuffin. In 1983, he released The Right Stuff, a three-hour epic about the creation of the space program. Over the coming years, he would become known for his sexually liberated films: The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), a love triangle set against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia; Henry & June (1990), based on French author Anaïs Nin’s account of her relationship with Henry Miller and his wife, June; and his twisted Marquis de Sade tale, Quills (2000). In each case, Kaufman’s intelligence and distinctly European approach to filmmaking yield literate, richly crafted, and philosophically complex films.

When Kaufman set out to remake Invasion of the Body Snatchers with screenwriter W.D. Richter for United Artists, the San Franciscan could not help but use his chosen city as the backdrop. Kaufman and Richter relocated the plot from a fictional small town in California, where everyone knows everyone else and notices when someone has suddenly been replaced by an emotionless copy, to the sprawling metropolis of San Francisco. Set in the then-modern 1970s, the birthplace of Generation Me, the film finds everyone too preoccupied and self-involved to detect that something horrible is happening around them. Where better than the free-spirited San Francisco to set such a film, where emotionalism and open love transformed the city into a hub for self-analysis and gay rights? Home to “artists and eccentrics,” the San Francisco of this era housed people who were dedicated to individualism, yet who pursued their self-absorption in group therapy. Consider Erhard Seminars Training, commonly known as est (Latin for “it is”), later called “The Forum”—a movement rooted in self-education. Launched by Werner Erhard, a former salesman untrained in psychoanalysis, psychiatry, or self-help, est held popular seminars that went on for several days, consisting of 15-hour long brainwashing sessions with participants deprived of restroom and meal breaks, conversations with anyone but the instructor, and formed a kind of “cult of the Self” that demanded personal enlightenment—and in the end, they were asked if they “got it.” People did, hundreds of thousands of people, in fact. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that the first est course was held in San Francisco, nor that, in her original review of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Pauline Kael called Erhard “the original spore.”

Kaufman’s film opens with a sequence straight out of Atomic Age science fiction. Somewhere in deep space, wispy spores take flight from a dying planet and float across the galaxy until they fall to Earth as tiny gelatinous blobs. They drip off plants like gobs of KY Jelly and soon reach out with wiry roots that, in time, form a miniature pod from which an enticing flower blooms. Should someone come into contact with the flower and fall asleep with it nearby, they would be duplicated in a pod and reborn as part of an alien hive mind, while their original body would be sent to the garbage heap as cottony, gray dust. And when the ever-growing collective identifies those who show emotion or resist, they release a banshee scream, not of this earth, and the chase begins. Such conformity creatures have never had a more fitting home than San Francisco, which, at the time, besides the Generation Me individualist movement, was in the midst of a significant urban expansion project that resulted in the Transamerica Pyramid in 1972, among other notable architecture. Continuing into the 1980s, gentrification reshaped the cityscape and, incongruously to the Generation Me movement, separated people from one another, creating physical and social borders. Generation Me fed on the isolation that enhanced its fetishized indulgence of the Self. The entire city looked outward at their community with suspicion and confusion, wondering, Who are these people? with an appropriate level of paranoia.

Amid an entire culture that’s bent on self-discovery but no longer knows who their friends and family are, Elizabeth (Brooke Adams), a Department of Health lab technician, asks, Who is this sleeping in my bed? In an early scene, she picks one of the unique alien flowers and places it beside the bed next to her inattentive husband, Geoffrey (Art Hindle), an already distant spouse. If he was remote before, when Geoffrey wakes up the next morning, he seems like another person altogether. Later, Elizabeth confesses to friends that “something is missing” in her marriage to her stone-faced partner—a perfectly logical reaction of paranoia for an unhappy couple, according to newly published self-help author Dr. Kibner (Leonard Nimoy), a haughty celebrity whose hypotheses are reinforced by his devoted circle of friends. Kibner’s convincing psychobabble explains away enough to quell Elizabeth’s immediate doubts. After all, perhaps her misgivings are in some way connected to her crush on her boss at the Department of Health, Matthew (Donald Sutherland), who’s well aware of her feelings. When she comes over late one night, Matthew cooks her stir-fry and asks her when her husband is getting home. When she admits that she was told not to wait up, Matthew offers her more wine, and they both smile knowingly. Less convinced is Jack (Jeff Goldblum), a moodily struggling poet who owns a Turkish Bath with his equally oddball wife Nancy (Veronica Cartwright), both of whom are a little high-strung. Jack is more apt to believe Elizabeth’s vague conspiracy theory. What’s a conspiracy, you ask? “Everything,” says Jack. Beneath the thrills and justified paranoia in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a strain of self-aware filmmaking courses through characters who find the capacity to laugh about the absurdity of the situation they’re in.

Already a culture suspicious of “norms” and unemotional, robotic behavior, when signs of a greater conspiracy emerge, the San Franciscans’ typical self-importance becomes a source of justifiable doubt. Elizabeth is convinced of a conspiracy, but her descriptions of mysterious meetings where parcels are passed between strangers are almost verbatim what a paranoiac would say. So, we doubt her, in a way, despite what we’ve seen, in part because Kaufman presents evidence from her perspective. After all, Kibner’s explanation is persuasive: Elizabeth is “looking for an excuse to get out” of her marriage, which is true enough. But all of Kibner’s justifications come crashing down when Jack and Nancy find an unformed duplicate of Jack growing in their parlor, slimy and covered in a white hair-like material. Matthew, too, arrives at Elizabeth’s just in time to carry her away from Geoffrey, before her pod person has time to fully form. Now convinced and on the run, the four of them hole up at Matthew’s and, while sleeping in shifts, nearly lose themselves to duplication. They try to seek Kibner’s help, but it’s too late; he’s one of them. And as they escape a crowd of screeching pod people, Matthew stays behind a moment to destroy the adult, fetus-like replicants of his friends; though he can’t bring himself to smash Elizabeth’s duplicate, he smashes his imposter in an act of self-obsessed destruction. Each time someone turns, it’s terrible because Kaufman has done an excellent job of making them likable. These are peculiar, multifaceted people, both the characters and their actors, and they’re presented in a film that views them through an atypical lens.

Kaufman complicates each scene beyond its surface, whether he incorporates some visual or aural flourish in the background or activates a scene with humor and paranoia. His actors seem to realize the fantastical sci-fi outlandishness of the story they’re in. Cartwright, as brilliantly unhinged as she was in Alien a year later, belts out her (accurate) plantlife alien invasion theory: “Why do we always expect metal ships?!” Jack replies dryly, “I’ve never expected metal ships.” In another scene, Kaufman places Matthew before a funhouse mirror at a book party as he tries to call the police about an accident he witnessed earlier; next to him, Jack spouts on about his artistic integrity (with Goldblum in perfect form, anticipating his performances in The Fly and Jurassic Park), and the moment of overlapping dialogue next to the funhouse image is pure surreality. In a more thrilling flourish, Kaufman channels Alfred Hitchcock by cutting back and forth between pod people following Matthew and Elizabeth on a city street. As the two speed up, their clacking is exaggerated for effect, and we see the feet of their pursuers speeding up in unison, until both parties reach a sprint. Kaufman also incorporates playful cameos: Robert Duvall, who had starred in Kaufman’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, appears as an ominous priest on a swing; the original’s director Don Siegel plays a cab driver; and Kevin McCarthy picks up where he left off in the 1956 version, running down the street and shouting “You’re next!” to anyone who will listen. McCarthy’s rather dreamlike appearance suggests Kaufman’s film is less a remake than a continuation of the original. Still, it also demonstrates how much fun the director is having with the material.

At the end of Kaufman’s film, the poet becomes a hero as Jack leads their pursuers away, and Nancy follows after him. Finally, realizing their mutual love in their last hopeless moments, Matthew and Elizabeth struggle to stay awake until “Amazing Grace” plays on a ship at the dockyards. Perhaps they can escape by boat. Matthew leaves Elizabeth alone to get a better look and sees drones loading pods onto the ship for an overseas journey. When he returns to Elizabeth, he finds her asleep and cannot wake her—her duplicate has already formed. Matthew resolves to rush headlong into a nearby pod factory and set it ablaze, but after he narrowly escapes, the last shots find us wondering how Matthew made his getaway. The next images show him going about his routine blankly at the Department of Health. He could just be acting to remain hidden in plain sight—that’s what we tell ourselves anyway. We follow him outside, and when a variation of “Amazing Grace” starts up, given the tune’s established correlation with false hope, we should already know what Nancy is in for when she spots Matthew in the park. She rushes up to him, overjoyed to see a familiar face. And the last shot of Matthew raising his arm and screaming that horrible scream remains one of the most jarring, upsetting, and still-effective moments in cinema history. No other technical element has a more haunting impact than that hideous alien scream—an unnerving shriek that announces exposure, betrayal, and terror in a singular aural nightmare.

With a budget of under $3.5 million, and a sizeable portion of that going to the haunting post-production sound FX achieved by sound designer Ben Burtt (of Star Wars fame), Kaufman relies on frantic, inventive camerawork, his cast’s dynamic and funny performances, and his mischievous filmmaking style to bring the material to life. Take a wonderfully bizarre moment where Matthew accidentally kicks a pod that’s absorbing the banjo-playing beggar and his pooch; we see the result of Matthew’s poor footing when, as he and Elizabeth hide in a crowd of pod people, a dog with a human face runs up and shocks Elizabeth out of her emotionless act, and the chase begins again. Cinematographer Michael Chapman’s frenzied handheld style shines in kaleidoscopic, head-spinning sequences on bustling city streets where everyone is a duplicate, and no one will listen to Matthew’s crackpot story about an alien takeover. Jazz musician Denny Zeitlin brings a weird, uncanny quality to his only film score, at times using dissonant sounds and at others, a breath-like tempo. Zeitlin was so exhausted by his experience of recording music for a film that he vowed never to do it again, and he kept that vow. When United Artists released Invasion of the Body Snatchers on December 20, 1978 (with a surprising PG rating, given the nudity, goopy practical effects, and head-smashing gore), it went on to make nearly $25 million at the box office. It received reviews that often deemed it superior to the original. The critic for Variety wrote that it “validates the entire concept of remakes.” But The New Yorker‘s Pauline Kael wrote the most impassioned assessment, and though deemed guilty of hyperbole, she accurately stated that it “may be the best film of its kind ever made.” And many more of this kind were made, including Abel Ferrara’s aloof take on Finney’s novel with Body Snatchers in 1993, and the troubled Joel Silver production The Invasion (2007), which has more in common with Kaufman’s film than the source material. All of them, including the original, stand in the shadow of Kaufman’s version.

In her exceptional analysis of John Carpenter’s The Thing for the British Film Institute, Anne Billson wrote, “great horror movies are like Frankenstein’s monster—considerably more than just the sum of their tacked-together body parts.” And Philip Kaufman transforms Invasion of the Body Snatchers from an effective remake of a paranoid ’50s sci-fi tale into an intertextual narrative and film-watching experience. Moreover, it belongs on a shortlist with Carpenter’s The Thing, David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), and Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991), of Hollywood remakes that surpass their predecessors. Its body parts have been carefully sewn together, every facet electro-shocked with creativity. It lives and breathes like no other adaptation of Finney’s novel has done before or after. Along with its many technical and idiosyncratic flourishes, Kaufman and Richter utilize their specific setting so that everything onscreen feels awakened from its familiar slumber. Though the film embraces and slyly satirizes the idea of individualism, it also underscores how individualism remains under constant attack by conformist ideologies. More than Red Scare paranoia, or any other metaphors the various adaptations of Finney’s novel may have inspired, Kaufman’s approach contains a distinct theme. While in many ways it remains specific to the film’s particular setting, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also a timeless, fantastically entertaining, and richly assembled thriller that still feels vital and alive today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review