The Definitives

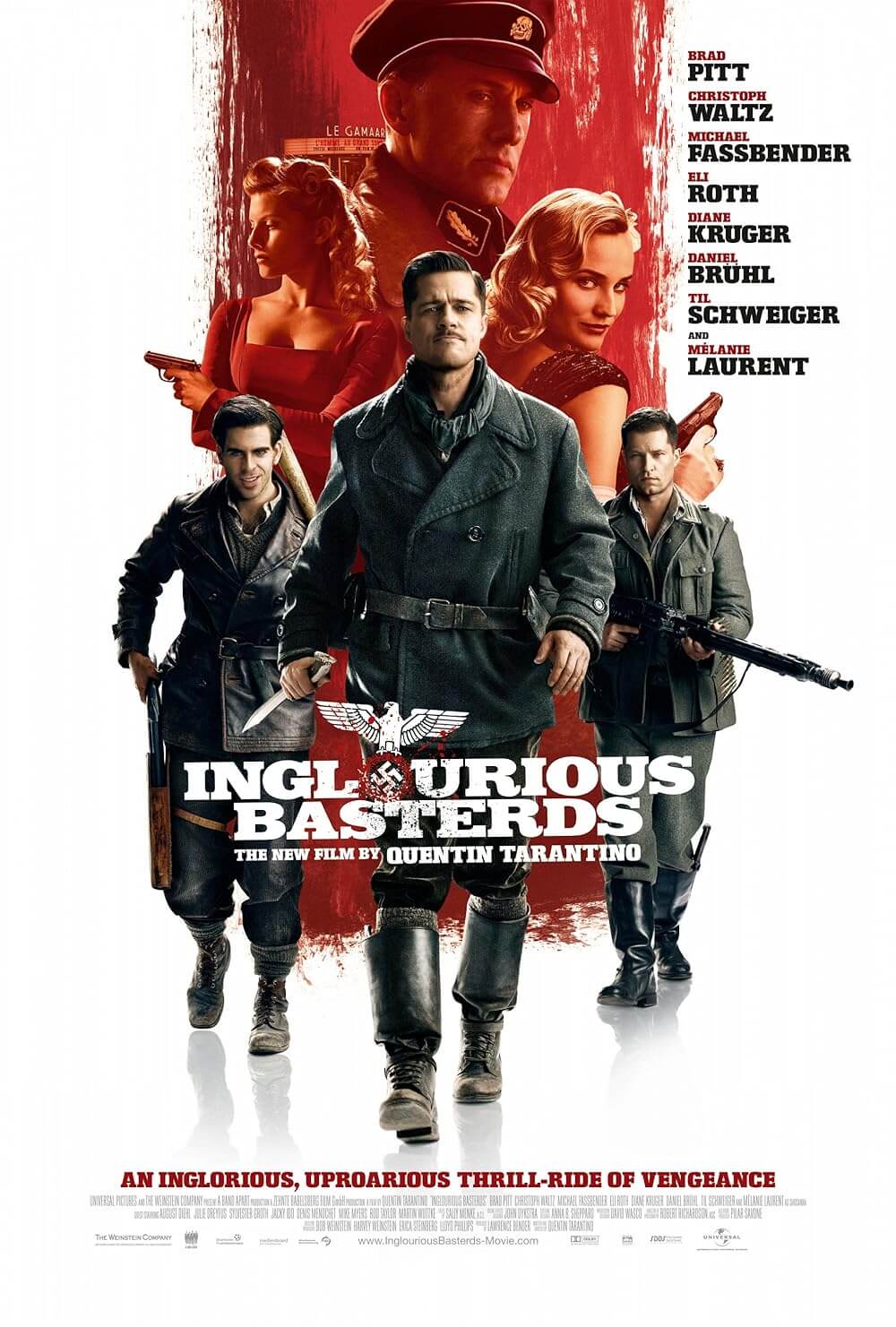

Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

After negotiating his conditional surrender with American military command, Colonel Hans Landa of Hitler’s SS rides in the passenger’s seat of a German truck headed for the Allied border and regards the Bowie knife of his transitory prisoner, Lt. Aldo Raine. Leader of the Jewish-American commandos known as the “Inglourious Basterds”, Raine has made it his business to hunt down and kill every Nazi to cross his path (“And boy, bid’ness is a boomin’”). By order of his superiors, Raine and his fellow Basterd will take over the truck at the border; once there, Landa “The Jew Hunter” and his driver will surrender freely and Raine will drive them to an American HQ for debriefing. All does not go according to plan. Instead, Raine’s Basterd Utivich cuffs Landa and shoots the German driver dead. Raine cannot abide the thought of a Nazi negotiating a pardon to escape the punishment of war crimes, even if, like Landa, he has helped orchestrate the demise of Hitler’s Third Reich. To ensure this Nazi wears his crimes like a uniform for the rest of his life, Raine takes his Bowie knife, the very one Landa was admiring a moment ago, and repeats what he’s done to countless other Nazi soldiers before by slicing a swastika deep into Landa’s forehead. When he’s finished, Raine smiles and says, “You know somethin’, Utivich? I think this just might be my masterpiece.”

When he wrote this last line of his screenplay, Quentin Tarantino must have felt the same way about Inglourious Basterds, a film which embodies all the traits of a great Tarantino film, yet also encompasses the director’s palpable love for cinema within its plot. Through his signature use of extended and involving dialogue sequences, textual and subtextual references to films and film history, and a storyline dependent on cinema in both figurative and literal fashion, this masterpiece signifies in body and soul what it means to be a Quentin Tarantino film. Consider just the opening credits, presented in an assortment of fonts and colors each employed on his earlier films from Reservoir Dogs to Kill Bill; these titles alone announce the film as a culmination of Tarantino’s body of work. In their individual ways, every Tarantino film is “about” cinema, whether he incorporates specific stylistic influence into the picture or casts an admired former cult actor to revive their career; his characters discuss films in their protracted pop-culture conversations, and his cinematic apparatus occupies styles crafted by earlier masters. Film is the lifeblood of Tarantino’s cinema, and this has never been truer than in Inglourious Basterds, where film theory, history, and narrative combine into a magnificent whole.

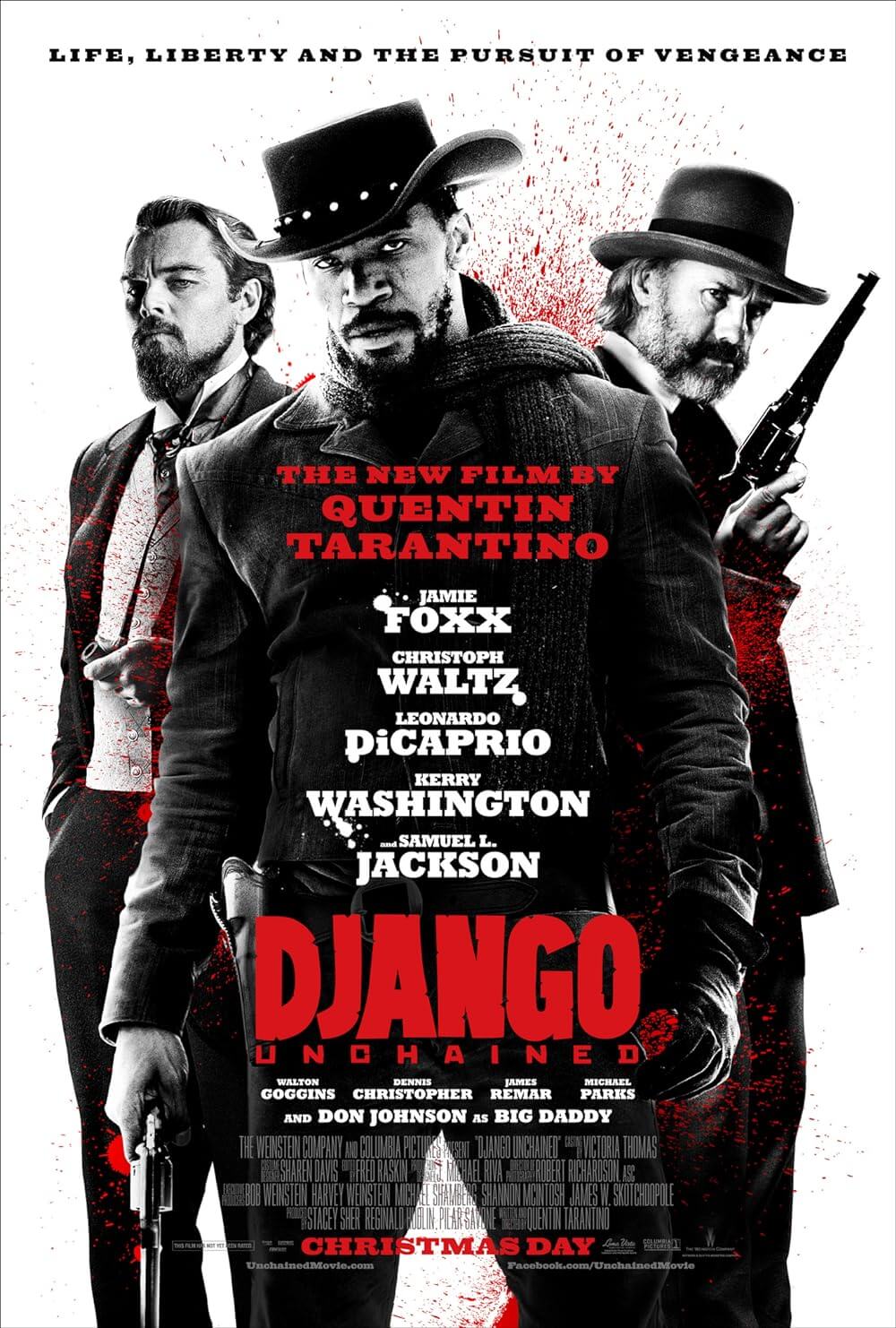

A long-in-development production, Tarantino labored over the script for nearly ten years before finally committing his story to film, completing Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2 (2004-5) and his Grindhouse (2007) contribution Death Proof in the meantime. Knowing the importance of the subject matter and the story’s potential to become something profound within his body of work, he waited for the right moment. A cineaste at heart, Tarantino is nothing if not aware of his presence in the film community and how every new picture he makes redefines his growing career. Early on, the director was certain Inglourious Basterds could be his masterpiece. With the artistic eyes of Oliver Stone and Martin Scorsese’s longtime cinematographer Robert Richardson and Tarantino’s own recurrent production designer David Wasco behind the camera, his certainty became a reality. Filmed for around $70 million for The Weinstein Company and distributed by Universal Pictures, the production went on to become Tarantino’s most successful picture to date, due in large part to the presence of star Brad Pitt and the inbuilt draw for audiences to see Nazis receive their comeuppance—a poster featuring Pitt atop a pile of Nazi corpses signified as much. The film earned upwards of $320 million in receipts worldwide, and the next year received eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay. Inglourious Basterds was almost universally hailed as one of Tarantino’s finest pictures yet. And in the short time since it’s release, the film has surpassed even Pulp Fiction as the director’s most highly regarded motion picture.

A long-in-development production, Tarantino labored over the script for nearly ten years before finally committing his story to film, completing Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2 (2004-5) and his Grindhouse (2007) contribution Death Proof in the meantime. Knowing the importance of the subject matter and the story’s potential to become something profound within his body of work, he waited for the right moment. A cineaste at heart, Tarantino is nothing if not aware of his presence in the film community and how every new picture he makes redefines his growing career. Early on, the director was certain Inglourious Basterds could be his masterpiece. With the artistic eyes of Oliver Stone and Martin Scorsese’s longtime cinematographer Robert Richardson and Tarantino’s own recurrent production designer David Wasco behind the camera, his certainty became a reality. Filmed for around $70 million for The Weinstein Company and distributed by Universal Pictures, the production went on to become Tarantino’s most successful picture to date, due in large part to the presence of star Brad Pitt and the inbuilt draw for audiences to see Nazis receive their comeuppance—a poster featuring Pitt atop a pile of Nazi corpses signified as much. The film earned upwards of $320 million in receipts worldwide, and the next year received eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay. Inglourious Basterds was almost universally hailed as one of Tarantino’s finest pictures yet. And in the short time since it’s release, the film has surpassed even Pulp Fiction as the director’s most highly regarded motion picture.

Set in France during World War II, the film opens, like many a Tarantino film, with a chapter structure. Chapter 1, called “Once Upon a Time in Nazi Occupied France”, takes place in 1941 and the Ennio Morriconne score alludes to the slow-burning build of a Sergio Leone Western. On the LaPadite farm, Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) engages in polite interrogation with the resident Monsieur (Denis Ménochet) who is suspected of housing Jews; the suspect breaks and those in hiding all die by Nazi bullets—all except Shosanna (Mélanie Laurent), who escapes on foot. Chapter 2, called “Inglourious Basterds”, takes its name like the film’s title from the misspelled etching on part-Apache-blooded leader Lt. Aldo Raine’s (Brad Pitt) rifle butt. Raine sermonizes to his seven Jewish-American recruits the assignment given to his unit: to kill Nazis with a vengeance and strike fear into the Nazi through a bloody guerilla campaign which, in time, gathers Hitler’s attention. Chapter 3, “German Night in Paris”, picks up in 1944, where Shosanna has taken the identity of “Emmanuelle Mimieux”, a moviehouse owner in Paris. Her beauty catches the eye of German war hero and film buff Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl), and through him a Nazi event is arranged at Shosanna’s theater in which key members of the Third Reich will be in attendance—the premiere of Zoller’s story on film, called Nation’s Pride. Shosanna plans to use the event to destroy those attending, among them Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth).

The British have the same idea in Chapter 4, “Operation Kino”, wherein film-critic-turned-officer Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender) heads a mission with two of Raine’s Basterds in German dress. They arrange to rendezvous with famous German actress and Allied spy Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger), but their quiet meet in a basement bar is interrupted by an SS Major, Dieter Hellstrom (August Diehl), who sees through Hicox’s performance. After a bloody shootout, only Von Hammersmark survives, and she’s left to carry out the mission with Raine and two other Basterds, “The Bear Jew” Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth) and Omar Ulmer (Omar Doom), disguised as Italian filmmakers. Von Hammersmark informs them Adolf Hitler will be in attendance at the premiere, making the event too significant a target to pass up, despite their poor Italian vocabulary. In Chapter 5, “Revenge of the Giant Face”, Shosanna has prepared her trap along with her lover-projectionist Marcel (Jacky Ido): once Nation’s Pride reaches the fourth reel, homemade footage of Shosanna will announce the impending doom of all inside the theater by a Jewish woman’s hands, while behind the silver screen Marcel lights flammable nitrate prints. Unbeknownst to her, the Basterds have strapped themselves with dynamite for the same result. Also present, Landa calls out Von Hammersmark and kills her as a traitor, and then he proves to be a defector himself when he captures Raine and Private Utivich (B.J. Novak) only to arrange his conditional surrender to the American government. Behind the scenes of Shosanna’s cinema, Marcel lights the film stock on cue and incites panic in the audience, while Donny and Omar unload their clips into Hitler, Goebbels, and the Nazi moviegoers. The entire building explodes into flames. Hitler is dead. For all intents and purposes, the war is over. As for Landa, we know how that ends…

The British have the same idea in Chapter 4, “Operation Kino”, wherein film-critic-turned-officer Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender) heads a mission with two of Raine’s Basterds in German dress. They arrange to rendezvous with famous German actress and Allied spy Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger), but their quiet meet in a basement bar is interrupted by an SS Major, Dieter Hellstrom (August Diehl), who sees through Hicox’s performance. After a bloody shootout, only Von Hammersmark survives, and she’s left to carry out the mission with Raine and two other Basterds, “The Bear Jew” Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth) and Omar Ulmer (Omar Doom), disguised as Italian filmmakers. Von Hammersmark informs them Adolf Hitler will be in attendance at the premiere, making the event too significant a target to pass up, despite their poor Italian vocabulary. In Chapter 5, “Revenge of the Giant Face”, Shosanna has prepared her trap along with her lover-projectionist Marcel (Jacky Ido): once Nation’s Pride reaches the fourth reel, homemade footage of Shosanna will announce the impending doom of all inside the theater by a Jewish woman’s hands, while behind the silver screen Marcel lights flammable nitrate prints. Unbeknownst to her, the Basterds have strapped themselves with dynamite for the same result. Also present, Landa calls out Von Hammersmark and kills her as a traitor, and then he proves to be a defector himself when he captures Raine and Private Utivich (B.J. Novak) only to arrange his conditional surrender to the American government. Behind the scenes of Shosanna’s cinema, Marcel lights the film stock on cue and incites panic in the audience, while Donny and Omar unload their clips into Hitler, Goebbels, and the Nazi moviegoers. The entire building explodes into flames. Hitler is dead. For all intents and purposes, the war is over. As for Landa, we know how that ends…

Foremost in any Quentin Tarantino film are his unique characters, and the actors playing them have rarely been better cast or more vividly portrayed outside of Inglourious Basterds. Pitt’s brutalism and Tennessee twang as Aldo Raine might be over-the-top comical if there weren’t aspects about his character that remained a mystery; the scar around his neck, for example, looks as though he may have been strung up by a noose at some point. Could his Apache blood have made him the focus of Southern bigotry back home, and thus inspired his formation of the “Inglourious Basterds”? Nevertheless, his vicious yet just moral position on Nazism represents a decisive eye-for-an-eye logic, responding to savagery with savagery. Pitt manages to be heroic, funny, and a badass all at once, all while making the audience forget about his star prowess. Whereas Laurent’s heroine is more delicate and elegant as one might expect. Laurent, a Jewish Frenchwoman attracted to the role for obvious reasons, plays Shosanna at a distance out of necessity, her rage toward the Nazis hidden until Tarantino wonderfully steps out of the period: Over a montage of Shosanna preparing for vengeance at the premiere of Nation’s Pride, Tarantino plays David Bowie’s “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” and the line “Putting out a fire with gasoline” becomes wryly appropriate. The only characters filled with more rage might be “The Bear Jew”, a Jewish Bostonian who unleashes his hatred with a baseball bat, or perhaps Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger), who seems to brim with inner fury and earns his own cutaway to explain his savage backstory.

As for the Nazis, Groth’s Joseph Goebbels is a grotesque, cackling creature whose affections for Martin Wuttke’s absurdist Hitler border on a homoerotic or at least a childlike desire for approval. Zoller may show some sign of humanity when he walks out of Nation’s Pride, but he only does so to flirt with and then assault Shosanna; he might even be charming had Tarantino not reminded us of his vanity and self-importance toward his feat of killing dozens of Allied soldiers from a bell tower. But the most despicable of all Nazi characters in Inglourious Basterds, and perhaps in all cinema must be Landa (yes, worse even than Hitler), Tarantino’s egocentric Nazi version of Sherlock Holmes. The character smokes an absurdly large ivory pipe and questions his subjects with a smile, “Are you aware of my existence?” Waltz, who earned his first Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for playing Landa (his second Oscar was for the heroic Dr. King Schultz in Tarantino’s Django Unchained), is playful yet monstrous in the role. A seemingly charming sort, he smiles through penetrating questions as though he’s asking sardonically, but then he expects an answer. His Landa loves the chase, and teems with joy when he’s successful in his job as “Jew Hunter”, occasionally bursting with pleasure and pride. In the opening chapter, he lets survivor Shosanna sprint away from the site of her family’s execution, though he could easily follow her by automobile, and smiles as he cries out “Au revoir, Shosanna!”—as if he knows they will meet again. Or consider the transparent rouse at the opening of Nation’s Pride, when Landa laughs hysterically at Von Hammersmark when she claims she hurt her gunshot leg while mountain climbing; Landa teases the Basterds about their poor Italian accents, enjoying himself and deceptively disarming an intense situation for the viewer. Landa is evil; he knows it, and he savors every moment of it.

As for the Nazis, Groth’s Joseph Goebbels is a grotesque, cackling creature whose affections for Martin Wuttke’s absurdist Hitler border on a homoerotic or at least a childlike desire for approval. Zoller may show some sign of humanity when he walks out of Nation’s Pride, but he only does so to flirt with and then assault Shosanna; he might even be charming had Tarantino not reminded us of his vanity and self-importance toward his feat of killing dozens of Allied soldiers from a bell tower. But the most despicable of all Nazi characters in Inglourious Basterds, and perhaps in all cinema must be Landa (yes, worse even than Hitler), Tarantino’s egocentric Nazi version of Sherlock Holmes. The character smokes an absurdly large ivory pipe and questions his subjects with a smile, “Are you aware of my existence?” Waltz, who earned his first Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for playing Landa (his second Oscar was for the heroic Dr. King Schultz in Tarantino’s Django Unchained), is playful yet monstrous in the role. A seemingly charming sort, he smiles through penetrating questions as though he’s asking sardonically, but then he expects an answer. His Landa loves the chase, and teems with joy when he’s successful in his job as “Jew Hunter”, occasionally bursting with pleasure and pride. In the opening chapter, he lets survivor Shosanna sprint away from the site of her family’s execution, though he could easily follow her by automobile, and smiles as he cries out “Au revoir, Shosanna!”—as if he knows they will meet again. Or consider the transparent rouse at the opening of Nation’s Pride, when Landa laughs hysterically at Von Hammersmark when she claims she hurt her gunshot leg while mountain climbing; Landa teases the Basterds about their poor Italian accents, enjoying himself and deceptively disarming an intense situation for the viewer. Landa is evil; he knows it, and he savors every moment of it.

None of these unforgettable performances would be possible without Tarantino’s sharp dialogue. His film is structured around dialogue insofar that action seems to occur only after long stretches of monologue or conversation in surprise bursts. When Raine rallies his troops, Pitt’s drawl-laden delivery serves as characterization for the overall cathartic effect of Inglourious Basterds: “We will be cruel to the Germans, and through our cruelty, they will know who we are. And they will find the evidence of our cruelty in the disemboweled, dismembered, and disfigured bodies of their brothers we leave behind us. And the German won’t not be able to help themselves but to imagine the cruelty their brothers endured at our hands, and our boot heels, and the edge of our knives. And the German will be sickened by us, and the German will talk about us, and the German will fear us. And when the German closes their eyes at night and they’re tortured by their subconscious for the evil they have done, it will be with thoughts of us they are tortured with… Sound good?!” On the flipside, Landa’s cruelty in his poised, carefully rationed Nazi justifications not to mention his pride in his work, but validate Raine’s bloody retribution. When Landa borrows a page from Mein Kampf to compare Jews to rats for M. LaPadite, he almost succeeds in making us believe he admires, or perhaps just pities Jews because they are hunted and yet they know how to survive. Like Hitler, Landa’s oral wordsmithing convinces the fearful and weak-minded, and represents incomparable villainy.

Indeed, if historical evidence wasn’t enough, motion pictures have helped transform Nazis into the ultimate cinematic villains. In countless escapist and historical war films from the Golden Age of cinema and beyond, Nazis represent inhuman villainy—Nazism, what Anton Walbrook’s Kretschmar-Schuldorff called “the most devilish idea ever created by a human brain” in The Life and Dead of Colonel Blimp (1943). The iconography of the swastika alone signifies absolute evil. Take how the holy Arc of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark burns away the purely evil swastika printed on its wooden crate; director Spielberg also provides an explosive demise to his Nazi foes in the film, a sort of escapist lark for the Jewish filmmaker of Schindler’s List. History, however, was not as considerate as Spielberg or Tarantino were to their respective audiences. Unresolved tension has lingered ever since 1945 with anticlimactic word that Hitler was suspected to have shot himself before his body was burned by Russian soldiers, all before it could be photographed. How unsatisfying. In allowing the viewer to experience Hitler being gunned down and detonated, and what’s more killed inside a cinema, Tarantino acknowledges history’s shortcoming and in doing so speaks to the therapeutic quality of cinema. What Tarantino achieves narratively in Inglourious Basterds is unprecedented, both in history and the history of film. Hitler’s death, punctuated with a brief shot of his face pummeled by bullets, provides the ultimate cinematic catharsis that countless war movies have failed to deliver; not only does the act itself feel rewarding, but Tarantino’s reformation of history finally satisfies unresolved tensions in a way only films can. This use of polarized evil by way of Nazis reinforces the limitless possibility of cinema, the artifice of the artform, and the director’s absolute celebration of these qualities.

Indeed, if historical evidence wasn’t enough, motion pictures have helped transform Nazis into the ultimate cinematic villains. In countless escapist and historical war films from the Golden Age of cinema and beyond, Nazis represent inhuman villainy—Nazism, what Anton Walbrook’s Kretschmar-Schuldorff called “the most devilish idea ever created by a human brain” in The Life and Dead of Colonel Blimp (1943). The iconography of the swastika alone signifies absolute evil. Take how the holy Arc of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark burns away the purely evil swastika printed on its wooden crate; director Spielberg also provides an explosive demise to his Nazi foes in the film, a sort of escapist lark for the Jewish filmmaker of Schindler’s List. History, however, was not as considerate as Spielberg or Tarantino were to their respective audiences. Unresolved tension has lingered ever since 1945 with anticlimactic word that Hitler was suspected to have shot himself before his body was burned by Russian soldiers, all before it could be photographed. How unsatisfying. In allowing the viewer to experience Hitler being gunned down and detonated, and what’s more killed inside a cinema, Tarantino acknowledges history’s shortcoming and in doing so speaks to the therapeutic quality of cinema. What Tarantino achieves narratively in Inglourious Basterds is unprecedented, both in history and the history of film. Hitler’s death, punctuated with a brief shot of his face pummeled by bullets, provides the ultimate cinematic catharsis that countless war movies have failed to deliver; not only does the act itself feel rewarding, but Tarantino’s reformation of history finally satisfies unresolved tensions in a way only films can. This use of polarized evil by way of Nazis reinforces the limitless possibility of cinema, the artifice of the artform, and the director’s absolute celebration of these qualities.

The mere presence of Nazis implies danger, hatred, and a sense of unease in the moviegoer. Tarantino exploits these charactersitcs to enhance his film’s suspense in several cleverly orchestrated exchanges between a character concealing something and the Nazi trying to uncover the secret. Tarantino establishes a secret to heighten the fear of exposure, falling back on Alfred Hitchcock’s archetypal description for creating suspense—where a droll conversation unfolds between two friends, while under the table the camera reveals a bomb ticking away; the boring conversation goes on and on, but, conscious of the bomb, the audience is rapt by the tedious talk as they wait for the explosion. When Landa interrogates dairy farm owner M. LaPadite in the first scene, Tarantino suddenly heightens the routine questions when his camera pulls down under the table, and then under the floorboards, where Shosanna and her family hide in terror.

Later in Paris, Landa interviews “Emmanuelle Mimieux” about her cinema, and every question has us squirming as we wonder, Does he know it’s Shosanna? He even orders a glass of milk for her, intimating that he knows she would enjoy milk, being from a dairy farm. But this is just suspense-wrought coincidence. In the French bar where Hicox and the Basterds meet Von Hammersmark, Hellstrom insists upon writhing chitchat wherein he questions Hicox about his strange German accent. All the while, the audience reels with fright at the notion that Hicox and the tightly wound others might blow their cover, which, of course, they do. To further intensify the situation, Tarantino’s humor leaves us to laugh through feelings of tension; how hilarious it is to watch Von Hammersmark, Hicox, and the Basterds play an absurd drinking game while being grilled by Hellstrom. Finally, in Shosanna’s cinema, the Basterds have literal bombs fasted to their ankles and will likely be exposed at any moment; in this case, the audience wants the bomb to go off to destroy Hitler, and we fear that it may not because of Landa’s presence at the premiere.

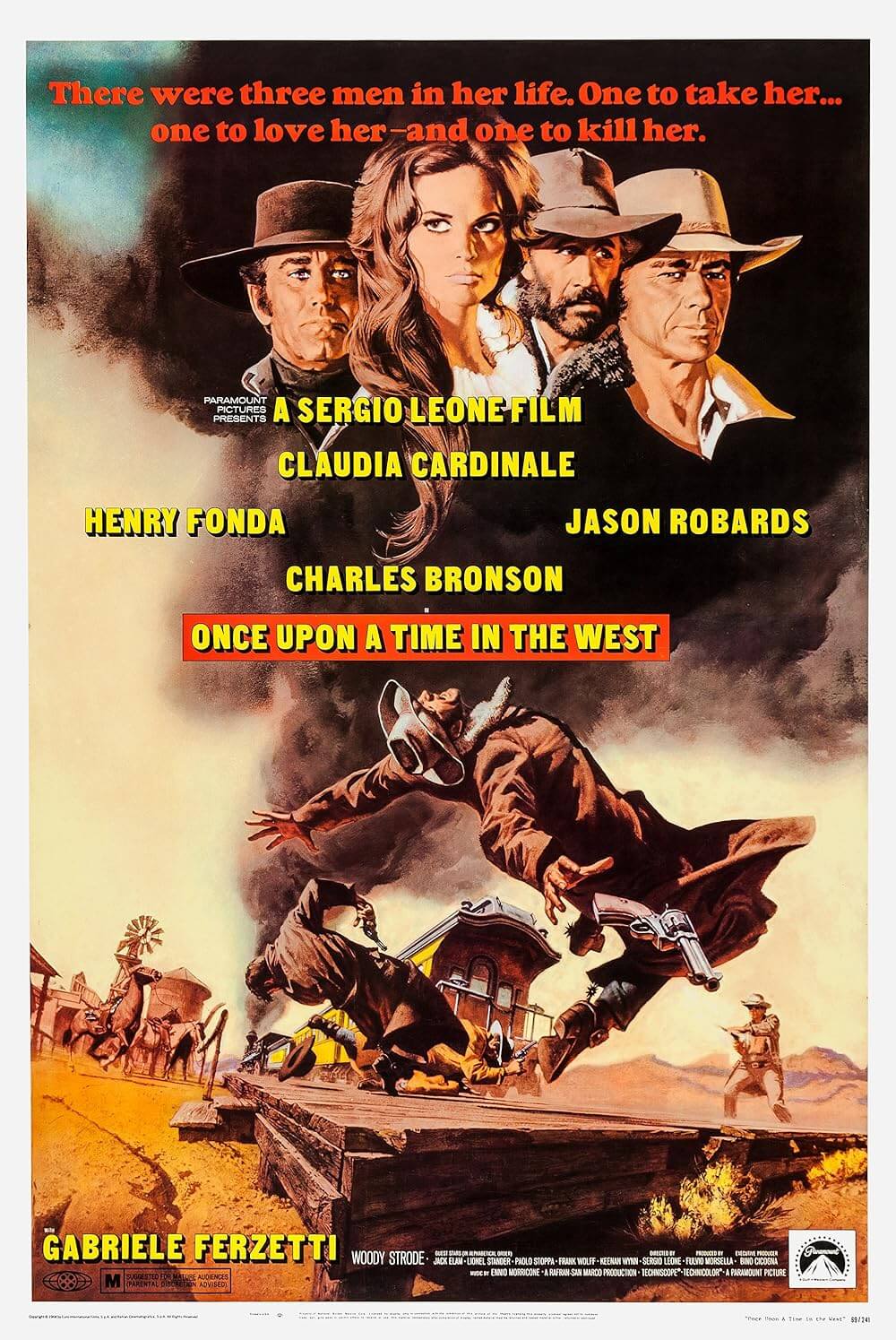

The way Tarantino winds us up with suspense and then gives us a false sense of security with a laugh is pure genius, and also pure Hitchcock. In these smart applications of Hitchcock’s definition for suspense, Tarantino underscores his knowledge and playfulness within the craft. Another Hitchcock reference highlights his enthusiasm for cinema itself even further: After Shosanna and Marcel discuss plans to detonate their moviehouse by setting fire to her massive collection of 35mm nitrate film prints, a cutaway (narrated by Samuel L. Jackson) explains that nitrate prints burn three times as fast as paper and shows a brief clip from Hitchcock’s Sabotage, his 1938 thriller where a young boy brings film canisters onto a trolley car and he’s told that it’s forbidden because films are flammable; a moment later, the boy’s package of canisters explodes, having contained a bomb. Shosanna setting ablaze her nitrate prints behind her theater’s screen represents the ultimate bomb-under-the-table scenario, but the film references and borrowed scenes do not end there. Consider Hicox’s debriefing in British headquarters, conducted by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers) and none other than Winston Churchill (Rod Taylor, The Birds star coaxed out of retirement for a single Tarantino line), a scene full of intentionally stereotypical Brit witticisms and epigrams. One cannot watch this scene without recalling a similar debrief from The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) in which the sole American, played by William Holden, feels overwhelmed by his superiors’ estimation of the oncoming suicide mission as a “jolly good show”. With moments like these in Inglourious Basterds, another filmmaker might be accused of pilfering; for Tarantino, it’s a celebration of cinematic trends through his own unique, often humorous understanding. Even the title nods toward Enzo G. Castellari’s The Inglorious Bastards from 1978, a B-actioner starring Bo Svenson and Fred Williamson, whereas the first chapter title “Once Upon a Time in Nazi Occupied France” pays homage to the Western elements in the sequence’s tonal similarities to Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968).

The way Tarantino winds us up with suspense and then gives us a false sense of security with a laugh is pure genius, and also pure Hitchcock. In these smart applications of Hitchcock’s definition for suspense, Tarantino underscores his knowledge and playfulness within the craft. Another Hitchcock reference highlights his enthusiasm for cinema itself even further: After Shosanna and Marcel discuss plans to detonate their moviehouse by setting fire to her massive collection of 35mm nitrate film prints, a cutaway (narrated by Samuel L. Jackson) explains that nitrate prints burn three times as fast as paper and shows a brief clip from Hitchcock’s Sabotage, his 1938 thriller where a young boy brings film canisters onto a trolley car and he’s told that it’s forbidden because films are flammable; a moment later, the boy’s package of canisters explodes, having contained a bomb. Shosanna setting ablaze her nitrate prints behind her theater’s screen represents the ultimate bomb-under-the-table scenario, but the film references and borrowed scenes do not end there. Consider Hicox’s debriefing in British headquarters, conducted by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers) and none other than Winston Churchill (Rod Taylor, The Birds star coaxed out of retirement for a single Tarantino line), a scene full of intentionally stereotypical Brit witticisms and epigrams. One cannot watch this scene without recalling a similar debrief from The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) in which the sole American, played by William Holden, feels overwhelmed by his superiors’ estimation of the oncoming suicide mission as a “jolly good show”. With moments like these in Inglourious Basterds, another filmmaker might be accused of pilfering; for Tarantino, it’s a celebration of cinematic trends through his own unique, often humorous understanding. Even the title nods toward Enzo G. Castellari’s The Inglorious Bastards from 1978, a B-actioner starring Bo Svenson and Fred Williamson, whereas the first chapter title “Once Upon a Time in Nazi Occupied France” pays homage to the Western elements in the sequence’s tonal similarities to Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968).

Film history plays a referential role in Inglourious Basterds, as discussed, but it also ornaments the setting of Tarantino’s film, particularly scenes in Paris. His sequences on the French countryside with the LaPadite family or the Basterds’ interrogation and scalping of several Nazi officers were designed to resemble those spare European locales used in countless Spaghetti Westerns, often shot on empty streets and near dilapidated architecture. For scenes around Shosanna’s cinema, the backdrop is littered with French movie posters and romantic cobblestone streets. To appease her Nazi occupiers, Shosanna screens films by German filmmakers Leni Reifenstahl, the skilled propaganda director behind The Triumph of the Will (1935), and also pictures by G.W. Pabst, an early practitioner of German cinema whose contributions include Pandora’s Box (1929), The Threepenny Opera (1931), and discovering Greta Garbo. But when German night is over, Shosanna’s own selection is Le Corbeau, a 1943 picture by French filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot. Starring Pierre Fresnay and Ginette Leclerc, the film concerns a small town rocked by an anonymous poison pen letter writer and serves up a subtext filled with anti-informant messages. What better film for a clandestine member of the French Resistance? By filmic association, Shosanna’s beliefs are clear. Had doting German hero Fredrick Zoller been as versed in French cinema of the era as he was with German, he might have recognized earlier where Shosanna’s sympathies lie. Fortunately for Shosanna, like many Nazi’s Zoller remained uninterested in international art.

Motion pictures have always been about transporting the audience to another time or place, providing an escape, and doing so through a collaborative artform. The cinema of Quentin Tarantino perpetuates this with more energy and innovative flourishes than that of any other filmmaker, and therein supplies his audience with the raw effect of moviegoing. Moreover is the primal significance of Inglourious Basterds, which is never better described than when Raine remarks that watching The Bear Jew batter Nazi heads is the closest thing they have to going to the movies. But Tarantino elevates that experience through his profound understanding of the medium. Form follows function as he operates knowingly within the WWII genre of entertainment-therapy for the viewer, recalling numerous like-plotted adventures such as The Guns of the Navarone (1961) or Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967), and also layers the experience with intertextual meaning and carefully considered mise-en-scène. His efforts encompass the outcome of great cinema from a story written not only for its instant emotional connection, but for its intellectual understanding of how this relationship between a film and its viewer functions by setting a significant piece of his film within a moviehouse. In the last scene when Raine carves a swastika into Landa’s forehead, Tarantino’s camera occupies Landa’s point-of-view and, in a sense, the viewer has been imprinted by both Raine and Tarantino—by cinema’s capacity to affect us. Tarantino leaves a mark on his viewers, and in this moment his proclamation “I think this just might be my masterpiece” couldn’t be truer.

Motion pictures have always been about transporting the audience to another time or place, providing an escape, and doing so through a collaborative artform. The cinema of Quentin Tarantino perpetuates this with more energy and innovative flourishes than that of any other filmmaker, and therein supplies his audience with the raw effect of moviegoing. Moreover is the primal significance of Inglourious Basterds, which is never better described than when Raine remarks that watching The Bear Jew batter Nazi heads is the closest thing they have to going to the movies. But Tarantino elevates that experience through his profound understanding of the medium. Form follows function as he operates knowingly within the WWII genre of entertainment-therapy for the viewer, recalling numerous like-plotted adventures such as The Guns of the Navarone (1961) or Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967), and also layers the experience with intertextual meaning and carefully considered mise-en-scène. His efforts encompass the outcome of great cinema from a story written not only for its instant emotional connection, but for its intellectual understanding of how this relationship between a film and its viewer functions by setting a significant piece of his film within a moviehouse. In the last scene when Raine carves a swastika into Landa’s forehead, Tarantino’s camera occupies Landa’s point-of-view and, in a sense, the viewer has been imprinted by both Raine and Tarantino—by cinema’s capacity to affect us. Tarantino leaves a mark on his viewers, and in this moment his proclamation “I think this just might be my masterpiece” couldn’t be truer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review